The correlation between dimensions of work-related stress and demographic characteristics of employees in the public sector

Автор: Dijana Kolundzic

Журнал: International Journal of Management Trends: Key Concepts and Research @journal-ijmt

Статья в выпуске: 2 vol.3, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study explores the relationship between employees' demographic characteristics and the perception of work stress in the public sector, using the WSQ questionnaire. The analyzed stress dimensions include workplace influence, organizational conflicts, individual demands, and interference with free time. A sample of 62 respondents (aged 25 to 60) encompasses employees with varying work experience and positions. Understanding how demographic characteristics affect the perception and experience of work stress can aid in developing targeted interventions to reduce stress and improve employee well-being in the public sector. Personalized stress management strategies are essential for enhancing the work environment and achieving optimal employee performance. The results indicate a significant impact of gender and position, while work experience did not show a significant effect. The paper provides guidelines for developing stress management strategies specific to the public sector. Further research should include a larger sample and a more detailed analysis of other potential factors influencing work stress to develop more effective strategies for its reduction and the improvement of the work environment in the public sector.

Work stress, public sector, demographic characteristics, strategy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170206429

IDR: 170206429 | УДК: 159.944.4-057.16 | DOI: 10.58898/ijmt.v3i2.71-86

Текст научной статьи The correlation between dimensions of work-related stress and demographic characteristics of employees in the public sector

Work stress is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon that can be analyzed from various perspectives, including physiological, psychological, sociological, and behavioral. Physiologically, stress is defined as the nonspecific response of the body to any demand that disrupts homeostasis (Selye, 1973). Psychologically, according to Lazarus and Folkman (1984), stress arises when an individual perceives that the demands of a situation exceed their available coping resources. Sociologically, stress is considered the result of the interaction between the individual and the social context, where organizational factors such as culture and coworker support play a critical role (Pearlin et al., 1981).

-

*Corresponding author: dragana.curcicc@gmail.com

© 2024 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) .

Theoretical Approaches to Work Stress

Karasek's Demand-Control Model

One of the most important theoretical approaches to studying work stress is Karasek's DemandControl Model (1979). This model is based on the idea that stress occurs when job demands are high, and the control employees have over these demands is low. According to this model, when employees face high demands—such as intense work pressures, tight deadlines, and task complexity—while lacking sufficient control over how these tasks are performed, the result is increased stress levels, reduced engagement, and a higher likelihood of developing psychosomatic illnesses.

Karasek emphasizes that stress does not arise solely from the intensity of job demands but also from the lack of resources and control available to employees to meet those demands. This model has laid the foundation for further studies on organizational stress, particularly within industrial and bureaucratic settings.

Job Demands-Resources Model (JD-R Model)

Another key theoretical approach to studying workplace stress is the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, developed by Schaufeli and Taris (2014). This model builds upon Karasek's approach by emphasizing that stress is influenced not only by job demands but also by the resources employees have to cope with these demands. Employees who face high demands but also have sufficient support, resources, and autonomy are less likely to experience stress and burnout.

Theory of Cognitive Appraisal of Stress

One of the most important psychological approaches to stress is Lazarus and Folkman’s theory of cognitive appraisal of stress (1984). This approach emphasizes that stress is not merely the result of objective stressors but also the subjective experience of employees—how they assess whether they can cope with the demands imposed by their work environment. Lazarus and Folkman distinguish between two types of appraisal: primary and secondary.

Primary appraisal refers to how employees perceive a situation—whether as a threat, a challenge, or something insignificant. Secondary appraisal involves evaluating the resources available to cope with stress. This theoretical approach is significant because it highlights that stress is not triggered by universal factors but is subjective, depending on how employees assess the situation and their confidence in their ability to meet job demands. The model provides valuable insights into individual differences in stress perception and underscores that stress can be mitigated through the development of effective coping and adaptation strategies.

Physiological Aspects of Stress

McEwen and Sapolsky (1995) investigated the physiological aspects of stress, emphasizing its profound impact on employee health. Prolonged exposure to stress results in changes in body chemistry, including elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which can damage various bodily systems. These changes increase the risk of heart disease, depression, anxiety, and a weakened immune response.

The physiological consequences of stress can severely affect employees’ long-term health and also have adverse effects on organizations. Employees experiencing high-stress levels often demonstrate reduced productivity, higher absenteeism, and shorter career longevity. These findings underscore the importance of workplace stress management to protect employees and improve overall organizational productivity.

A Review of Previous Research on Workplace Stress

Studies on workplace stress in organizations highlight various sources of stress and their consequences for employee health and organizational productivity. Karasek's (1979) research emphasizes the importance of job autonomy, while studies by Cooper and Marshall (1976) confirm that workload overload, lack of support, and job insecurity are among the key factors contributing to workplace stress. McEwen and Sapolsky (1995) underscore the physiological consequences of stress, such as an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases and reduced immune system functionality, while Griffeth et al. (2000) demonstrate that workplace stress raises employee turnover rates.

Social factors, such as organizational culture, also play a crucial role in employees’ stress experiences. Hofstede (1980) showed that organizational culture can shape how employees perceive and respond to stress. This sociological approach highlights the importance of shared values and norms within an organization, which can reduce stress through enhanced collaboration and support among employees.

Research in Serbia, such as studies by Popov et al. (2013), indicates that employees in the country experience higher levels of stress compared to those in countries like the Netherlands and Denmark. These findings suggest that labor market specifics, along with social and cultural factors, significantly influence employees' stress experiences. Additionally, studies in countries such as the United Kingdom and Denmark show that organizations implementing stress-reduction strategies—such as flexible working hours and increased social support—are more successful in alleviating employee stress (Bultman et al., 2002; Black Report, 2008).

Materials and methods

This paper aims to provide a deeper insight into the phenomenon of workplace stress in organizations. The research focuses on four key areas: the impact of workplace stress, organizational conflicts, individual demands and commitment, and how work interferes with leisure time. The study sought to analyze the presence of workplace stress within Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS) and examine its relationship with the demographic characteristics of respondents, such as gender, work experience, and organizational position. Data collection was conducted using a questionnaire to assess employees' perceptions of these aspects of workplace stress.

The theoretical part of the paper analyzed contemporary literature on organizational stress, the history of stress research, medical and psychoanalytic approaches to stress, as well as the specifics of stress in the workplace. Additionally, it explored the stages of stress, sources of stress in organizations, stress indicators, consequences of workplace stress, the relationship between stress and job performance, and approaches to stress management. The research methodology was also subject to analysis.

The goal of this paper was to provide a comprehensive overview of the problem of workplace stress in organizations, investigate the latest findings in the fields of human resource management and occupational psychology, and identify best practices and strategies that organizations can adopt to effectively address this challenge, improving both their performance and competitiveness. The empirical part of the research focused on identifying differences in the perception of workplace stress based on the demographic characteristics of respondents. The study analyzed the influence of gender, years of work experience, and organizational position on various dimensions of workplace stress.

The subject of this research is to determine the presence of workplace stress within Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS). The focus is placed on four key areas: workplace impact, organizational conflicts, individual demands and commitment, and the interference of work with leisure time. Through the use of a questionnaire, the study explored employees' perceptions of these factors and their influence on work experience.

The objectives of our research was:

-

• To determine the impact of the respondents' gender on the dimensions of workplace stress.

-

• To identify differences in the dimensions of workplace stress based on the respondents' years of work experience.

-

• To identify differences in the dimensions of workplace stress based on the respondents' organizational position.

The hypotheses proposed in our research were as follows:

-

• H0: There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of workplace stress and

the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

-

• H1: There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of workplace stress

based on the respondents' gender.

-

• H2: There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of workplace stress

based on the respondents' years of work experience.

-

• H3: There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of workplace stress

based on the respondents' organizational position.

As a research instrument, the Work Stress Questionnaire (WSQ) (Frantz and Holmgren, 2019) was used, supplemented with questions related to respondent characteristics (gender, age, education, years of work experience, and organizational position).

The WSQ is a self-assessment tool for workplace stress that contains 21 closed-ended questions grouped into four dimensions of work stress:

-

1. Impact at Work: This dimension consists of four questions with a four-point response scale: "always," "often," "sometimes," "rarely," and "never." It examines the time employees have to complete tasks, their ability to influence decisions at work, whether their opinions are valued by superiors, and their capacity to control work pace.

-

2. Unclear Organization and Conflicts: This dimension contains seven questions with possible answers of "Yes," "Partially," or "No." The questions address workload, clarity of goals and tasks, awareness of decision-making processes, conflicts at work, involvement in conflicts, and the reactions of superiors to workplace conflicts. Each question is followed by a sub-question, answered only if the main question is affirmative, using a four-point stress scale: "not stressful," "slightly stressful," "stressful," and "very stressful." These sub-questions form a new dimension, Perceived Stress from Unclear Organization and Conflicts.

-

3. Individual Demands and Commitment: This dimension also consists of seven questions with the same responses and sub-questions as in the "Unclear Organization and Conflicts" dimension. The sub-questions form a new dimension, Perceived Stress from Individual Demands and Commitment. The questions assess the extent to which employees set high demands for themselves, their frequent work engagement, whether they think about work after hours, their ability to set work boundaries despite workload, whether they take on excessive responsibility, work overtime, and experience sleep problems due to work.

-

4. Work Interfering with Leisure Time: This dimension consists of three questions with responses on a four-point scale: "always," "quite often," "rarely," and "never." The questions examine how often work prevents employees from spending time with loved ones, friends, or engaging in recreational activities.

Data Analysis

Sample Demographics

The research sample consisted of 29% male and 71% female respondents. Over half were aged between 36 and 55, and one-sixth were under 26 years old. In terms of education, 48.4% had completed higher education, and just over 30% had completed secondary school. One-third of respondents had 11 to 20 years of work experience, while nearly a quarter had more than 30 years of experience. Regarding organizational positions, the majority indicated they held an operational role, while 8.1% were in senior management positions. Among women, one in nine worked in senior management, whereas no men reported holding such positions.

Research resultsWork Stress Dimension - Impact at Work

The Impact at Work Dimension was assessed through responses to four questions, with possible answers ranging from "yes, always" (value 1) to "no, never" (value 4).

Nearly half of the respondents indicated that they always have time to complete their work tasks, and 41.3% chose the response "quite often." One in ten respondents stated that they rarely or never have enough time to finish their work tasks.

Only 3.2% of respondents reported that they always have the ability to influence decisions at work, while 41.9% said they quite often do. More than 16% of respondents stated that they never have the ability to influence decisions at work.

Half of the respondents mentioned that their superiors quite often consider their opinions, while nearly a quarter reported that this happens always, which is important for a good work climate. However, one in four respondents said that their superiors rarely or never consider their views.

The largest number of respondents perform their work tasks at a pace that suits them, with 22.6% stating they always decide the pace of their work, and 61.3% saying they quite often have the opportunity to do so. Only one respondent reported that they can never influence the pace of their work.

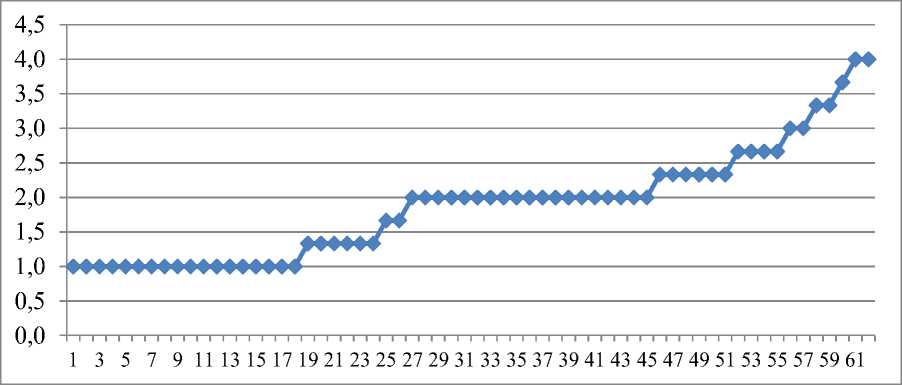

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15171921232527293133353739414345474951 5355575961

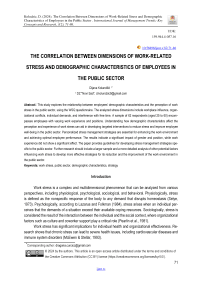

Figure 1. Average Values for the Impact at Work Dimension

By analyzing each individual questionnaire and the average values for the "Impact at Work" dimension, it is observed that most of the questionnaires had values ranging from 1.75 to 2.25. A high risk for the impact of work stress, meaning dimension values of 3 or 4, was noted in 22.6% of the questionnaires, with only one questionnaire reaching the maximum value of 4. The median value for the dimension was 2, indicating a low impact on the occurrence of work stress (see Figure 1).

When examining the relationship between the respondents' characteristics and the Impact at Work dimension, it is observed that there is a statistically significant difference based on gender and organizational position, while no such difference is found for work experience (Table 1).

Table 1. Relationship Between the Impact at Work Dimension and Respondents’ Characteristics

|

Respondents’ Characteristics |

(%) |

p |

||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|||

|

Gender |

male (n=18) |

0,0 |

55,6 |

38,9 |

5,6 |

<0,001 |

|

female (n=44) |

2,3 |

56,8 |

40,9 |

0 |

||

|

Up to 10 years. (n=12) |

0 |

41,7 |

58,3 |

0 |

||

|

Work Experi- |

11-20 years. (n=21) |

0 |

61,9 |

38,1 |

0 |

0,645 |

|

ence |

21-30 years. (n=14) |

0 |

57,1 |

35,7 |

7,1 |

|

|

>30 years. (n=15) |

6,7 |

53,3 |

40 |

0 |

||

|

Organizational Position |

Top managers (n=5) |

20,0 |

80,0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Middle-level managers (n=20) |

0 |

65,0 |

35,0 |

0 |

0,009 |

|

|

First line managers (n=37) |

0 |

45,9 |

51,4 |

2,7 |

||

Work Stress Dimension - Unclear Organization and Conflicts

The Unclear Organization and Conflicts Dimension was assessed through seven questions. The first four questions related to work overload, how familiar the respondent was with the goals of their work and tasks, and who makes the decisions that affect their job. The last three questions focused on conflicts. If the respondent indicated that there were no conflicts in the team, they answered only one question, as the other two related to whether they were personally involved in conflicts and what the superior’s response was to the given conflict. Each question had a sub-question ("Do you perceive this as stressful?"), which the respondent answered if they gave an affirmative response to the main question. The result of the sub-question formed a new dimension—perceived stress from the Unclear Organization and Conflicts dimension.

Regarding whether work overload had increased, 61.3% of respondents answered that it had not. Of those who felt that their work overload had increased, 2.6% found this situation not stressful at all, 60.5% found it mildly stressful, 28.9% found it stressful, and 7.9% found it very stressful.

64.5% of respondents stated that the goals of their job were clear. Among those who found their job goals unclear or partially clear, 9.1% found this very stressful, 27.3% found it stressful, and 63.6% found it mildly stressful.

One in five respondents indicated that their work tasks were unclear or only partially transparent, with 16.7% stating this was not stressful. However, this lack of clarity was mildly stressful for half of them, while for a third, it was either stressful or very stressful.

79% of respondents stated that they knew who makes decisions regarding their jobs. Among those who were unaware, 15.4% found this lack of knowledge very stressful, 7.7% found it stressful, and 69.2% found it mildly stressful.

22.6% of respondents reported that there were conflicts at the workplace, and three of them (4.8% of the sample) indicated that they had personally been involved in a conflict. When asked whether their superior did anything to resolve the conflicts, only those who confirmed the existence of conflicts responded. Among them, only 14.3% mentioned that there was a reaction from their superior, while the majority felt that no response was given.

Those respondents who stated that there were conflicts at their workplace had different stress reactions. For half of them, the occurrence of conflict was mildly stressful; for more than a third, specifically 35.7%, it was stressful; and for 14.3% of the respondents, it was very stressful. Of the 22.6% of respondents who reported conflicts at their workplace, three (4.8%) were themselves participants in the conflict, of which one felt mild stress and two felt stress.

Respondents who reported conflicts at their workplace, in 14.3% of cases, stated that their supervisor did something to resolve the conflicts. Those who believed that their supervisor did nothing to resolve the conflicts experienced mild stress in 33.3% of cases, stress in 58.3%, and high stress in 8.3%.

Perceived stress due to unclear organization and conflicts

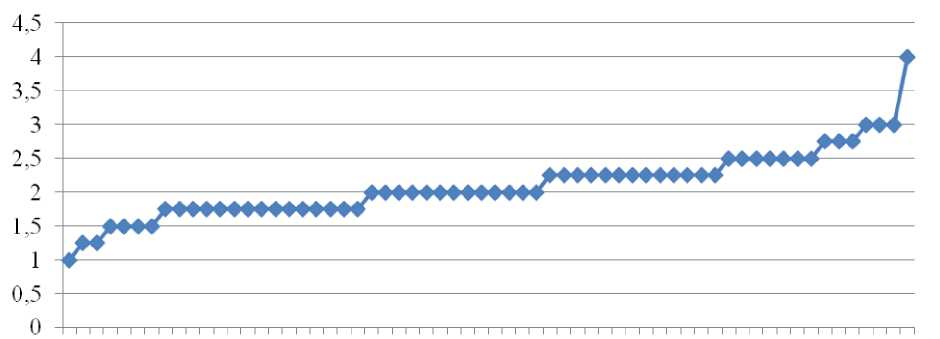

Perceived stress for the dimension of Ambiguous Organization and Conflicts was assessed based on the responses in each individual questionnaire. A high level of exposure was defined as a positive response to 4-7 questions, while a low level of exposure was defined as a positive response to 0-3 questions. A high level of stress exposure was recorded for 62.9% of respondents, with the median of the dimension being 4 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Perceived Stress for the Dimension of Ambiguous Organization and Conflicts

When examining the relationship between the respondents' characteristics and the dimension of Ambiguous Organization and Conflicts, it is observed that there is no statistically significant difference based on gender, work experience, or position in the organization (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation of the Dimension of Ambiguous Organization and Conflicts with the Respondents’ Characteristics

|

(%) |

||||||||||

|

Respondents Characteristics |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

p |

|

|

Gender |

male (n=18) |

0 |

5,6 |

5,6 |

22,2 |

38,9 |

27,8 |

0 |

0 |

0,357 |

|

female (n=44) |

2,3 |

4,5 |

22,7 |

9,1 |

29,5 |

31,8 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Work Experience |

up to 10 years. (n=12) |

0 |

8,3 |

8,3 |

25 |

25 |

33,3 |

0 |

0 |

0,753 |

|

11-20 years. (n=21) |

4,8 |

0 |

23,8 |

4,8 |

28,6 |

38,1 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

21-30 years. (n=14) |

0 |

14,3 |

0 |

14,3 |

50 |

21,4 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

>30 god. (n=15) |

0 |

0 |

33,3 |

13,3 |

26,7 |

26,7 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Organizational Position |

Top managers (n=5) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

40,0 |

60,0 |

0 |

0 |

0,173 |

|

Middle-level managers (n=20) |

4,8 |

4,8 |

28,6 |

0 |

19,0 |

42,9 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

First line managers (n=37) |

0 |

5,6 |

13,9 |

22,2 |

38,9 |

19,4 |

0 |

0 |

||

Dimension of Job Stress - Individual Demands and Commitment

The dimension of Individual Demands and Commitment was analyzed through seven questions, which addressed the expectations respondents set for themselves regarding their job, how engaged they are with work, whether they think about work after working hours, and similar topics. Each question had a sub-question ("Do you find this stressful?") to which respondents answered if they had affirmed the main question. The result of the sub-question formed a new dimension – Perceived Stress from Individual Demands and Commitment.

High job demands were set by 48.4% of respondents, of whom 36.7% found it not stressful, 46.7% found it a little stressful, and 16.7% found it stressful.

83.9% of respondents were frequently engaged in work, which was not stressful for 28.8%, a little stressful for 53.8%, and stressful for 13.5%. No respondent reported that frequent engagement with work was stressful. 56.6% of respondents thought about work after working hours. This was not stressful for 22.9%, a little stressful for 68.6%, and stressful for 5.7%, with 2.9% finding it extremely stressful.

Difficulties in setting boundaries for work tasks, despite having many tasks, were experienced by 58.1% of respondents. These difficulties were not stressful for 11.1%, a little stressful for 58.3%, stressful for 22.2%, and highly stressful for 8.3% of participants. More than half of respondents (53.2%) admitted to taking on more responsibility at work than they should, and 15.2% did not feel stressed about it. A little stress from taking on too much responsibility was felt by 57.6%, and 3% reported high stress.

30.6% of respondents said they worked after regular working hours to complete their tasks. This caused a little stress for 57.9%, while 31.6% reported no stress. Because their minds were preoccupied with work, 30.6% of participants reported having sleep problems. Of these, 73.7% experienced it as a little stressful, while 26.3% found it stressful.

Perceived Stress from Individual Demands and Commitment

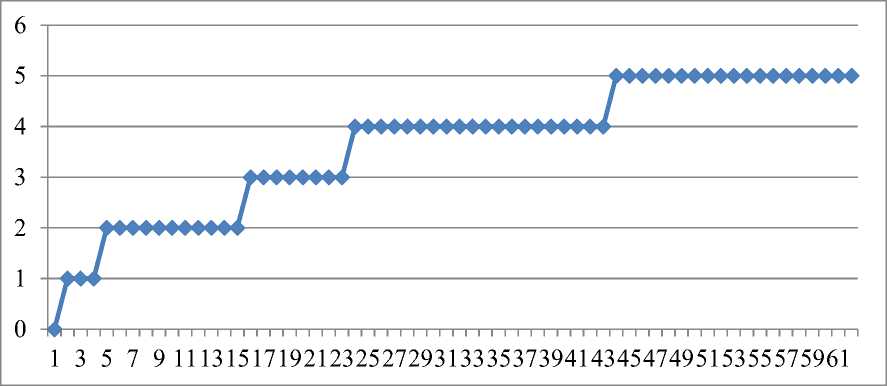

Perceived stress for the dimension of Individual Demands and Commitment was assessed based on the responses in each individual questionnaire, with a high exposure level defined as a score of 7 and a low exposure level defined as scores between 0-6. A high level of stress exposure was recorded for 9.7% of the respondents, while the median for this dimension was 3 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Perceived stress for the dimension of Individual Demands and Commitment.

When examining the relationship between the individual characteristics of the respondents and the dimension of Individual Demands and Commitment, it is observed that a statistically significant difference exists only in relation to the respondent's gender (Table 3).

Table 3. The Relationship Between the Dimension of Individual Demands and Commitment and the Characteristics of the Respondents

|

Оаоплн/1дп(о’ । h^HortfiKiefricc |

(%) |

|||||||||

|

Respondents Characteristics |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

p |

|

|

Gender |

male (n=18) |

16,7 |

5,6 |

16,7 |

22,2 |

16,7 |

5,6 |

5,6 |

11,1 |

<0,001 |

|

female (n=44) |

6,8 |

11,4 |

15,9 |

15,9 |

18,2 |

13,6 |

9,1 |

9,1 |

||

|

Work Experience |

up to 10 years. (n=12) |

8,3 |

8,3 |

16,7 |

33,3 |

0 |

25,0 |

8,3 |

0 |

0,601 |

|

11-20 years. (n=21) |

9,5 |

4,8 |

9,5 |

14,3 |

23,8 |

14,3 |

14,3 |

9,5 |

||

|

21-30 years. (n=14) |

7,1 |

14,3 |

14,3 |

14,3 |

21,4 |

21,4 |

7,1 |

0 |

||

|

>30 god. (n=15) |

13,3 |

6,7 |

6,7 |

13,3 |

20,0 |

6,7 |

6,7 |

26,7 |

||

|

Organizational Position |

Top managers (n=5) |

25,0 |

0 |

25,0 |

0 |

0 |

25,0 |

0 |

0 |

0,586 |

|

Middle-level managers (n=20) |

10,5 |

5,3 |

15,9 |

10,5 |

15,8 |

26,3 |

5,3 |

10,5 |

||

|

First line managers (n=37) |

2,7 |

10,8 |

8,1 |

24,3 |

21,6 |

10,8 |

13,5 |

8,1 |

||

Dimension of Work Stress - Work Interference with Free Time

The dimension of Work Interference with Free Time was examined through responses to three questions, with possible answers ranging from "Yes, always" (value 4) to "No, never" (value 1). Responses with values of 3 or 4 indicated an increased impact on stress.

4.8% of respondents stated that it is always difficult for them to find time to be with their loved ones due to work, while 11.3% reported this happening quite often.

Respondents were asked how difficult it is for them to find time to be with friends, with 4.8% answering "always" and 16.1% answering "quite often."

Work overload also affects recreational activities. 6.5% of respondents stated that it is always difficult for them to find time for recreational activities, while 14.5% said it is quite often difficult.

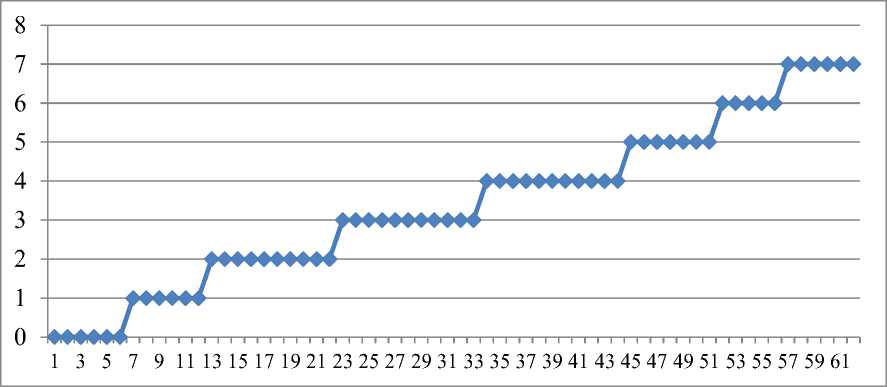

Figure 5 Display of the mean values for the dimension Work Interference with Free Time

Analyzing each individual questionnaire and the mean values for the Work Interference with Free Time dimension, it was observed that most questionnaires had values ranging from 1.75 to 2.25. A high risk for work stress, or values of 3 or 4 for this dimension, was observed in 27.4% of the questionnaires, with only two questionnaires having a maximum value of 4. The median value for this dimension was 2, indicating a low impact on work stress (Figure 5).

When observing the relationship between the respondents' characteristics and the dimension of Work Interference with Free Time, it is noted that there is a statistically significant difference only based on gender (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between the dimension of Work Interference with Free Time and the respondents' characteristics

|

Respondents' characteristics |

(%) |

|||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

p |

||

|

Gender |

male (n=18) |

38,9 |

33,3 |

22,2 |

5,6 |

0,008 |

|

female (n=44) |

25,0 |

50,0 |

15,9 |

9,1 |

||

|

Work Experience |

up to 10 years. (n=12) |

16,7 |

50,0 |

25,0 |

8,3 |

0,268 |

|

11-20 years. (n=21) |

33,3 |

38,1 |

14,3 |

14,3 |

||

|

21-30 years. (n=14) |

42,9 |

50,0 |

7,1 |

0 |

||

|

>30 god. (n=15) |

20,0 |

46,7 |

26,7 |

6,7 |

||

|

Organizational Position |

Top managers (n=5) |

40,0 |

40,0 |

20,0 |

0 |

0,324 |

|

Middle-level managers (n=20) |

45,0 |

30,0 |

20,0 |

5,0 |

||

|

First line managers (n=37) |

18,9 |

54,1 |

16,2 |

10,8 |

||

When considering the overall impact of the analyzed dimensions of work-related stress, it is observed that only the dimension of Perceived Stress due to Ambiguous Organization and Conflicts has a high impact on work stress among the employees included in the study (Table 5).

Table 5. The Impact of Work Stress Dimensions on the Occ urrence of Stre ss Among Respondents

|

Work Stress Dimensions |

Median |

Impact on Stress Occurrence |

|

Impact at Work |

2 |

low |

|

Stress due to unclear organization and conflicts |

4 |

high |

|

Stress from individual demands and commitment |

3 |

low |

|

Work interfering with free time |

2 |

low |

In relation to the research hypotheses, it is concluded that the respondent's gender impacted the work stress dimensions: Job Influence, Perceived Stress Due to Individual Demands and Commitment, and Work Disruption of Free Time. The position within the organization impacted the Job Influence dimension, while the respondents' years of work experience did not affect any of the work stress dimensions (Table 6).

Table 6. The Impact of Respondent Characteristics on Work Stress Dimensions

|

Work Stress Dimensions |

Gender |

Work Experience |

Organizational Position |

|

Impact at Work |

<0,001 |

- |

0,009 |

|

Stress due to unclear organization and conflicts |

- |

- |

- |

|

Stress from individual demands and commitment |

<0,001 |

- |

- |

|

Work interfering with free time |

0,008 |

- |

- |

Discussions

In this study, the dimensions of work stress were analyzed and their connection with the demographic characteristics of the respondents, including gender, years of work experience, and position in the organization. The survey included 62 people, of whom 71% were women and 29% were men. The respondents were predominantly aged between 36 and 55 years, with the largest group (48.4%) having completed a university degree. Additionally, one-third of the respondents had between 11 and 20 years of work experience, while 23% had more than 30 years of work experience. The study aimed to confirm, partially confirm, or not confirm the hypotheses. Based on the analysis, the following results were obtained.

Confirmation of Hypotheses:

H0 - There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of work stress and the demographic characteristics of the respondents. This hypothesis was partially confirmed. Gender and position in the organization had a statistically significant impact on specific dimensions of work stress, while years of work experience did not have a significant effect.

H1 - There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of work stress in relation to the respondent’s gender. This hypothesis was confirmed. Gender had a statistically significant impact on the dimensions of work stress: "Impact on the job," "Perceived stress due to individual demands and commitment," and "Work interfering with free time."

H2 - There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of work stress in relation to the years of work experience of the respondent. This hypothesis was not confirmed. Years of work experience did not have a statistically significant impact on any dimension of work stress.

H3 - There is a statistically significant difference between the dimensions of work stress in relation to the respondent’s position. This hypothesis was partially confirmed. Position in the organization had a statistically significant impact on the dimension "Impact on the job."

Conclusions

This research aimed to analyze the presence of work stress at Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS) and investigate its connection with the demographic characteristics of the respondents, such as gender, work experience, and position within the organization. A questionnaire assessed employees' perceptions of four key areas of work stress: impact on the job, organizational conflicts, individual demands and commitment, and work interfering with free time.

Based on the conducted research and a review of relevant literature, it can be concluded that work stress is a significant issue both globally and in Serbia. Demographic characteristics such as gender, work experience, and position in the organization can influence employees' perception of work stress. For example, women often report higher levels of work stress compared to men, which aligns with the findings of other studies. However, work experience was found to be a less relevant factor concerning work stress in this study, which differs from the results of other studies exploring this connection.

International research confirms the widespread prevalence of work stress, with serious implications for health and productivity. For example, data from Denmark and the United Kingdom show a high level of distress among workers, while research in Serbia points to even more alarming results. High levels of work stress are associated with poor health outcomes, absenteeism, and decreased productivity. Combining the results of this study with the conclusions of other studies, it is clear that policies and practices for managing work stress are vital both globally and within individual organizations. Investing in measures to reduce work stress and promote healthy work environments can significantly impact employee wellbeing and business outcomes.

Potential limitations of this research include the relatively small sample size and restrictions in the demographic characteristics covered. Future research could involve expanding the sample to obtain more representative results and a more detailed analysis of other potential factors that may affect work stress, such as socioeconomic status or type of job. Longitudinal studies could provide deeper insight into changes in the perception of work stress over time and identify the long-term effects of stress management on employee health and productivity.

In conclusion, this research contributes to the understanding of work stress in a specific work environment, but also highlights the need for further studies to understand better the factors contributing to work stress and develop more effective strategies for managing it.

Список литературы The correlation between dimensions of work-related stress and demographic characteristics of employees in the public sector

- Black Report. (2008). Working for a healthier tomorrow. London: TSO. Retrieved on 16 October 2014from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/209782/hwwb-working-for-a-healthier-tomorrow.pdf

- Bültmann, U., Kant, I. J., Van den Brandt, P. A., & Kasl, S. V. (2002). Psychosocial work char-acteristics as risk factors for the onset of fatigue and psychological distress: prospective results from the Maastricht Cohort Study. Psychological medicine, 32(2), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291701005098

- Cooper, C. L., & Marshall, J. (1976). Occupational sources of stress: A review of the literature relating to coronary heart disease and mental ill health. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 49(1), 11–28.

- Frantz, A., & Holmgren, K. (2019). The Work Stress Questionnaire (WSQ): Reliability and face validity among male workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 167–180.

- Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463-488. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600305

- Johnson, J. V., & Hall, E. M. (1988). Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. American journal of public health, 78(10), 1336–1342. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336

- Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285-308.

- Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- McEwen, B. S., & Sapolsky, R. M. (1995). Stress and aging: Mechanisms and strategies. Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences, 50A(3), 123-135.

- McEwen, B. S., & Stellar, E. (1993). Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 153(18), 2093-2101. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1993.00410180039004

- Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Menaghan, E. G., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337-356. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136676

- Popov, B., Stanojević, V., & Petrović, N. (2013). Workplace stress and job satisfaction in Serbia: The roles of organizational and personal factors. Industrial Health, 51(5), 482-491. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2013-0056

- Popov, B. (2018). Stres u radnom okruženju. Novi Sad, Srbija: Filozofski fakultet, Univerzitet u Novom Sadu. Str 11 Retrieved from https://digitalna.ff.uns.ac.rs/sadrzaj/2018/978-86-6065-464-1

- Richardson, K. M., & Rothstein, H. R. (2008). Effects of occupational stress management inter-vention programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(1), 69-93.

- Selye, H. (1973). The evolution of the stress concept. American Scientist, 61(6), 692-699. Re-trieved from [URL if applicable]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Psychological Health.