The export of Russian cotton fabrics and the commercial network of Asian merchants in the first half of the 19th century. Part 1

Автор: Shiotani M.

Журнал: Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: История, филология @historyphilology

Рубрика: Российская история

Статья в выпуске: 8 т.17, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper explores the development of the Russian cotton industry and export of its cotton fabrics in the first half of the 19th century. At a time when religion and ethnicity were a key basis for people, communication naturally proceeded between groups which shared religion and ethnicity and so Asian merchants assumed the trade between Russia and Asia between the 18th - 19th centuries. This was a commercial base for Asian merchants, operating businesses across borders. As Russia increased its trade with Asian regions, it used the commercial network of Asian merchants in neighboring countries. After power sources in Russia's cotton industry shifted from natural energy and animal power to fossil fuels, faster transportation was realized on a larger scale. This trend of transformation radically changed Russia's trade with Asia and heavily influenced the commercial network of Asian merchants.

Russia, 19th century, cotton industry, asian merchants, commercial network, xix век

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147220006

IDR: 147220006 | УДК: 94(47).072/073 | DOI: 10.25205/1818-7919-2018-17-8-49-64

Текст научной статьи The export of Russian cotton fabrics and the commercial network of Asian merchants in the first half of the 19th century. Part 1

During the process of studying the development of Russia’s cotton industry and its export of cotton fabrics in the first half of the 19th century, it was made clear that early industrialization was carried out under the serf system, and that the quantity of products in the cotton industry rapidly increased during this time. As a result of the industry’s development, Russian cotton fabrics were not only supplied to domestic markets, but also to Asian markets including Persia, Central Asia and China. When Russian cotton fabrics were exported to Asian markets, they were always transported through the Nizhny Novgorod Fair – Russia’s largest trade fair in those days. In previous Russian economic studies, researchers paid little attention to how Russian cotton fabrics were transported through Russia, and what kinds of merchants transported them to foreign markets and through which routes. Some local Russian historians have partially referred to the trade history between Russia and Asia, but the topic of Russian border trade still hasn’t been studied specifically.

Recently, the necessity for the topic of «Global History» has been advocated in economic history studies. Traditionally historians and their research units would focus on domestic history, which meant a lack of historical studies about activities over country borders. At present, globalization of economies moves and develops at such high speeds that the international historical view point tends to cross borders. Even today in Russian economic history, most researchers are dedicated to studying national history, while few make their mark in cross border studies. However, according to results of various conferences and symposia about this field published in Japan, cross border historical studies may be developed in future. The issue of what kinds of merchants exported Russian cotton

ISSN 1818-7919.

Вестник НГУ. Серия: История, филология. 2018. Том 17, № 8: История © M. Shiotani, 2018

fabrics through which trade routes is closely connected to the subject of «cross border history». This in turn has created a new research field in economic history studies.

While there have been very few research studies about «cross border history» within the field of Russian economic history studies, materials from existing studies, often overlooked by researchers contain enough information for this particular field of research. This article will mainly focus on the «Commercial Newspaper» as a key resource which was edited and published in the first half of the 19th century by the department of foreign trade in the Russian Ministry of Finance. The «Commercial Newspaper» was an efficient and fast way to communicate not only domestic economic information, but also information about foreign markets. As a result, this newspaper offers concrete information about trade between Russia and Asia during that specific time period. However, information about the export of Russian cotton fabrics to China may not be enough. Therefore, this article will also refer to the reports and articles of the «Ministry of Internal Affairs» and «Industry and Trade» magazines about Russian exports to China. These two magazines were published by the Russian government in the first half of the 19th century, and their information trustworthiness was considered to be very high.

It is also important to note the concept of a «nation» when we consider the trade history between Russia and Asia. Throughout the ages, Russia has been a state with many races with over 100 nationalities. However, when cotton fabrics were exported from Russia to Asian markets in the first half of the 19th century, not all nationalities were equally engaged in the export. It was ethnic merchants including Armenian, Bukharan and Siberian merchants who controlled the distribution route between Russia and Asia. This viewpoint that it was in fact ethnic merchants who carried out the export of Russian cotton fabrics to Asian markets is important in this article. It is also important to note that these merchants were not always of Russian descent; some were of foreign nationality. This form of distribution did not originate in the 19th century – this commercial network took centuries to establish. Based on information of the «Commercial Newspaper», the history and structure which the Russian Empire shared with Asian regions will be explained further in this article.

Before examining the commercial network between Russia and Asia, it is important to briefly summarize some previous research about the subject in order to understand the importance of the commercial network in Russian trade. As it is widely known, cotton can only be cultivated under certain climate conditions [Shoji, 1938. P. 2]. Up until the first half of the 19th century, Russia did not have fields with the necessary climate conditions to cultivate cotton. Therefore, neighboring regions of Persia and Central Asia were hopeful lands to undertake such an activity. Russia was first introduced to cotton fabrics produced in Persia and Central Asia in the 16th century [Brokgauz, Efron, 1991. P. 285]. Europe had been importing cotton yarn from Central Asia and weaving cotton fabrics since the 17th century, however at this time Russia was still yet to reach the stage of importing, spinning and weaving cotton. In the 18th century, cotton fabrics were exported to Russia from China and were consumed mainly in Siberia.

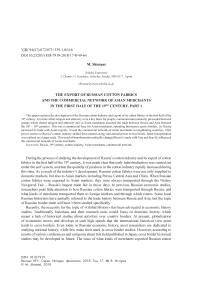

In the late 18th century, English yarn was imported to Russia. Once Russia started to weave their own cotton fabrics using English yarn, it marked the beginning of the modern cotton industry [Yatsunsky, 1959. P. 127]. In the first half of the 19th century, the first Russian cotton mill was established in St. Petersburg. The mill was so successful that others went on to be established not only in St. Petersburg, but also in Moscow and Vladimir [Ibid. P. 176]. Until the early 1840s, the export of English spinning machinery was prohibited, and therefore Russia imported most of its spinning machinery from France and Belgium. Although Russia imported American cotton through England which increased its cotton yarn production, Russia still continued to import cotton yarn from England. After Russia’s import of American cotton and production of cotton yarn increased in the first half of the 19th century, the quantity of domestic cotton yarn production surpassed the quantity of English cotton yarn imports in the early 1840s (Table 1, Fig. 1). After this, the proportion of domestic cotton yarn used within the country’s cotton yarn production gradually increased.

Table 1

|

Years |

Imports of raw cotton |

Russian production of cotton yarn |

Imports of cotton yarn |

|

1801–1805 |

11 |

7 |

60 |

|

1806–1810 |

41 |

26 |

58 |

|

1811–1815 |

106 |

81 |

129 |

|

1816–1820 |

58 |

44 |

191 |

|

1821–1825 |

70 |

58 |

236 |

|

1826–1830 |

103 |

88 |

432 |

|

1831–1835 |

149 |

130 |

560 |

|

1836–1840 |

320 |

281 |

589 |

|

1841–1845 |

527 |

461 |

590 |

|

1846–1850 |

1 115 |

976 |

351 |

|

1851–1855 |

1 669 |

1 460 |

118 |

|

1856–1860 |

2 622 |

2 294 |

217 |

Imports of raw cotton and cotton yarn and the amount of Russian cotton production (1800–1860) (thousand pood)

thousand pood

Imports of raw cotton

^—Imports of cotton yarn

■ Russian production of cotton yarn

Fig. 1 . Imports of raw cotton and cotton yarn and the amout of Russian cotton production (1800–1860).

Based on: [Arima, 1973. P. 174, 175; Yatsunsky, 1959]

As the cultivation of hemp and flax was always possible under Russia’s climate conditions, its textiles had long been utilized as cheap materials. However due to the establishment of cotton mills and the introduction of steam engines, mass production of cotton yarn was quickly realized. As a direct result, the price of cotton yarn decreased and cotton fabrics became much cheaper products, in direct competition with the previously affordable hemp and flax textiles. In particular, entrepreneurs in Moscow and Vladimir endeavored to produce cotton fabrics suitable for peasants, supplying them through fairs to the mass market [Arima, 1973. P. 174, 175]. At the time, the modern distribution network was virtually nonexistent, therefore traders undertook the selling of cotton fabrics from producers, traveling alongside city and country fairs, distributing the fabrics to consumers. The scale and frequency of the fairs would vary, however Russia’s biggest domestic fair – the Nizhny Novgorod Fair operated annually for a month from June to July [Bogoroditskaya, 1989]. When cotton fabrics were dispatched to foreign or distant markets, they always went through the Nizhny Novgorod Fair.

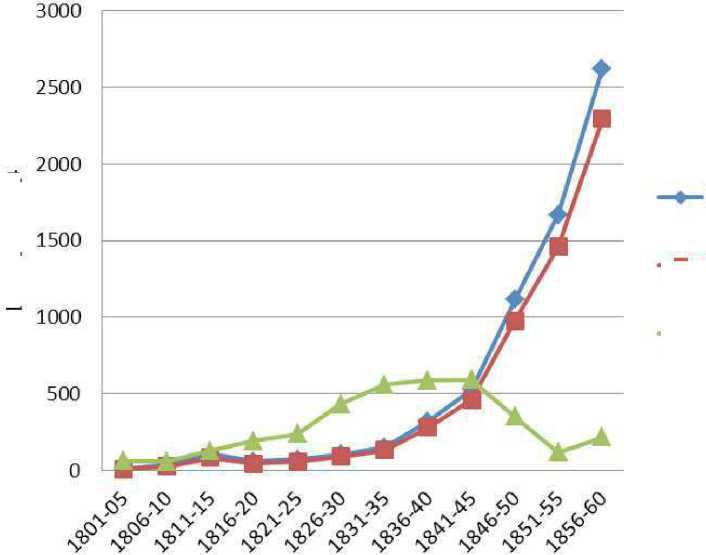

The Nizhny Novgorod Fair played the function of the main hub within the domestic fairs network. The goods traded at the Fair were distributed through several fairs to distant markets [Mironov, 1981]. The Fair not only integrated the domestic markets, but also undertook the role of an intermediary between the Asian and Russian markets. Therefore, various Russian and Asian goods accumulated in this Fair. As a testament to the Fair’s scope and influence, a special mention should be made about the Nizhny Novgorod Fair’s historical trade data which reports that the amount of cotton fabrics trade increased by 200% over a 30 year period from 1831 to 1860 (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 2

The transactions of Russian commodities in the Nizhny Novgorod Fair (1828–1860) (thousand ruble)

|

Years |

Cotton fabrics |

Woolen goods |

Metals |

Fur and leather |

|

1831 |

28 001 |

6 020 |

22 091 |

8 489 |

|

1832 |

16 300 |

10 250 |

17 000 |

14 200 |

|

1833 |

32 282 |

11 460 |

17 162 |

13 607 |

|

1834 |

30 367 |

9 262 |

17 538 |

12 634 |

|

1835 |

29 000 |

8 000 |

12 290 |

10 400 |

|

1836 |

30 857 |

10 874 |

12 000 |

10 454 |

|

1837 |

27 743 |

11 009 |

21 128 |

9 720 |

|

1838 |

30 000 |

11 200 |

22 000 |

8 700 |

|

1839 |

28 544 |

12 725 |

22 390 |

9 389 |

|

1840 |

25 961 |

9 756 |

15 290 |

10 394 |

|

1841 |

25 678 |

12 069 |

26 601 |

10 639 |

|

1842 |

26 356 |

11 604 |

26 924 |

10 411 |

|

1843 |

26 431 |

11 434 |

22 849 |

10 293 |

|

1844 |

26 791 |

18 437 |

29 697 |

10 519 |

|

1845 |

30 116 |

18 994 |

29 161 |

13 348 |

|

1846 |

34 615 |

18 769 |

28 264 |

13 860 |

|

1847 |

34 319 |

16 090 |

28 399 |

14 201 |

|

1848 |

30 280 |

14 254 |

28 665 |

13 778 |

|

1849 |

30 646 |

15 532 |

21 237 |

17 321 |

|

1850 |

26 067 |

14 247 |

30 215 |

21 309 |

|

1851 |

29 943 |

14 316 |

37 939 |

22 631 |

Continuation of Table 2

|

Years |

Cotton fabrics |

Woolen goods |

Metals |

Fur and leather |

|

1852 |

33 763 |

14 943 |

40 208 |

23 577 |

|

1853 |

28 662 |

12 181 |

34 597 |

22 964 |

|

1854 |

24 587 |

13 845 |

34 029 |

19 989 |

|

1855 |

27 803 |

16 542 |

31 714 |

20 211 |

|

1856 |

20 747 |

13 602 |

36 443 |

22 385 |

|

1857 |

32 665 |

20 277 |

42 174 |

24 049 |

|

1858 |

45 638 |

23 151 |

42 752 |

29 607 |

|

1859 |

53 203 |

27 356 |

51 457 |

27 285 |

|

1860 |

60 206 |

27 591 |

51 126 |

30 091 |

-

• cotton fabrics

-

■ woolen goods

-

i— metals

)( fur and leather

Fig. 2 . The transactions of Russian commodities in the Nizhny Novgorod Fair (1828–1860).

Based on: (Kommercheskaya gazeta. 1831–1860; Zhurnal Ministerstva vnutrennikh del. 1831–1861)

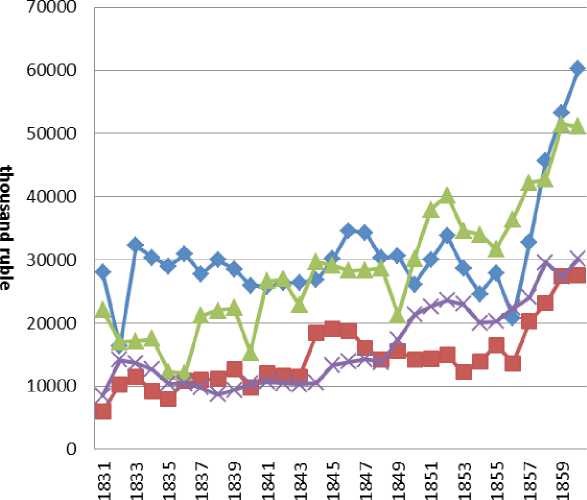

In the beginning of the 19th century, Russian products made of leather and fur were the most sought=after Russian goods traded in the Nizhny Novgorod Fair. As the cotton industry developed in Russia, the proportion of cotton fabrics in relation to other goods in Nizhny Novgorod gradually increased. After the 1830s, cotton fabrics became representative goods in the Fair. Cotton fabrics were not uniform goods, but were divided into several kinds. The trade amount of printed cotton, calico and scarves was high among cotton fabrics in those days (Table 3, Fig. 3). As the printed cotton and scarves were colorful products, these were usually used for women’s clothing.

Table 3

|

Years |

Printed cotton (ситец) |

Calico (миткаль) |

Scarf (платок) |

Velvet (плис) |

Canvas (холстинка) |

|

1831 |

20 400 |

1 237 |

1 846 |

– |

1 569 |

|

1832 |

7 700 |

1 650 |

– |

850 |

820 |

|

1833 |

7 600 |

1 681 |

10 105 |

– |

750 |

|

1834 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1835 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1836 |

9 100 |

1 610 |

9 124 |

1 108 |

675 |

|

1837 |

7 959 |

1 425 |

7 977 |

1 202 |

613 |

|

1838 |

14 988 |

1 459 |

3 664 |

1 383 |

624 |

|

1839 |

14 551 |

1 381 |

3 514 |

1 333 |

530 |

|

1840 |

13 051 |

1 667 |

4 324 |

1 149 |

364 |

|

1841 |

13 493 |

1 473 |

4 460 |

1 171 |

402 |

|

1842 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1843 |

11 844 |

712 |

3 026 |

1 346 |

2 136 |

|

1844 |

11 089 |

1 432 |

4 012 |

2 466 |

1 671 |

|

1845 |

11 661 |

1 366 |

4 791 |

2 447 |

1 847 |

|

1846 |

12 894 |

1 729 |

5 290 |

2 380 |

2 025 |

|

1847 |

13 318 |

1 640 |

5 335 |

2 283 |

1 470 |

|

1848 |

10 524 |

1 512 |

5 666 |

2 799 |

1 673 |

|

1849 |

11 142 |

2 125 |

6 384 |

1 971 |

879 |

|

1850 |

8 260 |

2 024 |

6 099 |

1 344 |

980 |

|

1851 |

8 960 |

2 610 |

6 830 |

2 118 |

1 035 |

|

1852 |

9 975 |

3 741 |

7 069 |

2 048 |

971 |

|

1853 |

9 030 |

3 460 |

6 888 |

1 085 |

945 |

|

1854 |

7 595 |

2 888 |

5 744 |

1 487 |

755 |

|

1855 |

7 000 |

2 825 |

4 725 |

438 |

749 |

|

1856 |

5 698 |

3 945 |

3 630 |

915 |

1 237 |

|

1857 |

10 136 |

7 007 |

4 854 |

1 568 |

1 645 |

|

1858 |

13 037 |

8 659 |

6 342 |

1 981 |

2 171 |

|

1859 |

14 672 |

9 282 |

6 461 |

2 331 |

2 362 |

|

1860 |

15 750 |

10 518 |

7 105 |

2 845 |

2 887 |

The transactions of Russian cotton fabrics in the Nizhny Novgorod Fair (1831–1860) (thousand ruble)

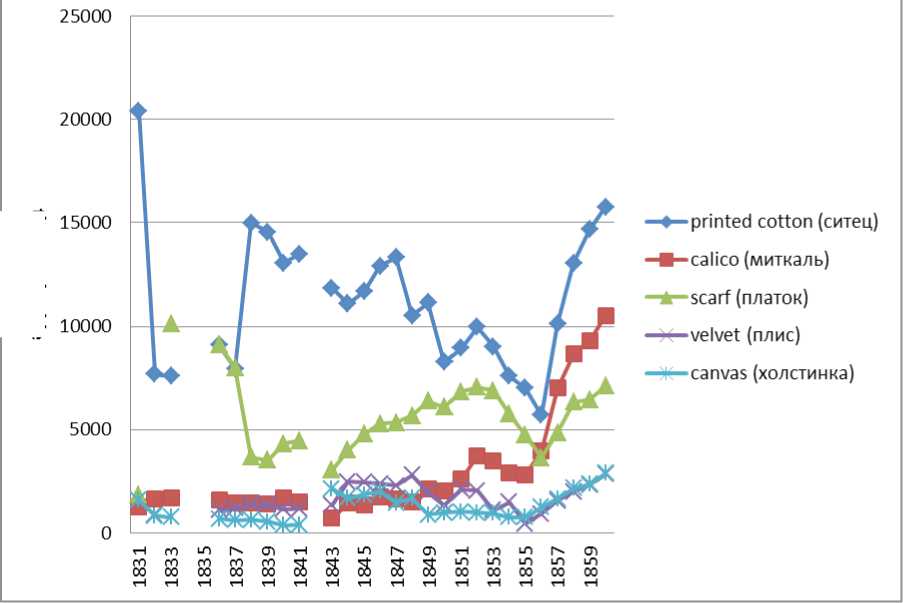

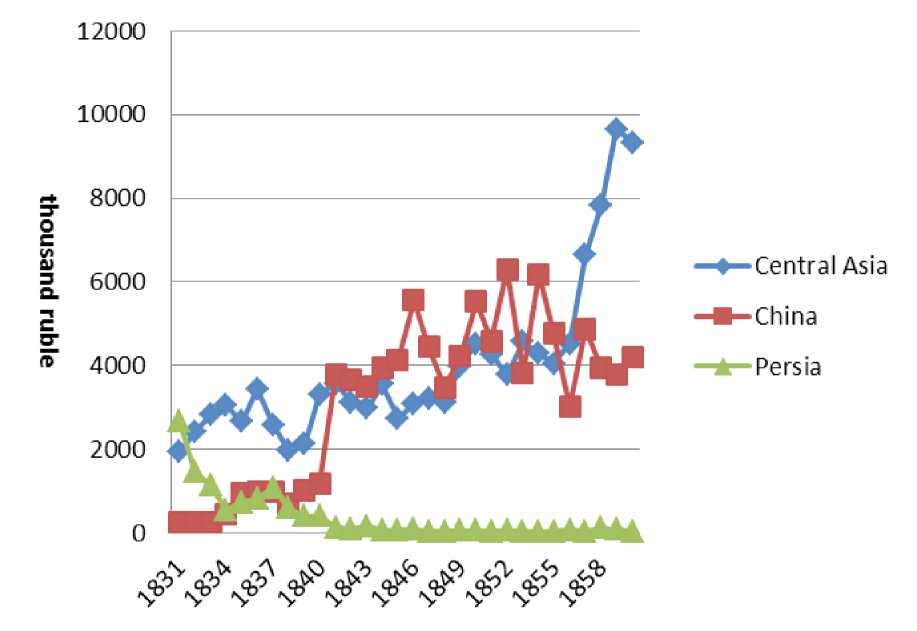

From the late 1820s, Russia’s export of cotton fabrics to Asian markets including Persia, Central Asia and China began through this Nizhny Novgorod Fair. Armenian merchants exported cotton fabrics to the Persian markets, Bukharan merchants – to the markets of Central Asia and Siberian and Shanxi merchants to the Chinese markets. While the export of Russian cotton fabrics to Persia showed the largest amount of trade among the country’s Asian trades in the beginning of the 1830s, the export of Russian cotton fabrics to China grew after the 1830s (Table 4, Fig. 4). While the export of Russian cotton fabrics to Central Asia increased in the 1850s, their export to Persia stagnated. Russian trade statistics made clear the amount of cotton fabrics export for each Asian market, but there was no research regarding which trade routes were used in the export process. The next section will trace each Asian market trade route and examine the history of the routes’ formation.

thousand ruble

Fig. 3. The transactions of Russian cotton fabrics in the Nizhny Novgorod Fair (1831–1860).

Based on: (Kommercheskaya gazeta. 1831–1860; Zhurnal Ministerstva vnutrennikh del. 1831–1861)

Table 4

Russian exports of cotton fabrics to Asia (1831–1860) (thousand ruble)

|

Years |

Central Asia |

China |

Persia |

|

1831 |

1 938 |

242 |

2 661 |

|

1832 |

2 418 |

245 |

1 466 |

|

1833 |

2 828 |

272 |

1 139 |

|

1834 |

3 056 |

450 |

554 |

|

1835 |

2 660 |

944 |

738 |

|

1836 |

3 445 |

996 |

814 |

|

1837 |

2 591 |

979 |

1 087 |

|

1838 |

1 961 |

697 |

595 |

|

1839 |

2 120 |

1 005 |

409 |

|

1840 |

3 322 |

1 190 |

410 |

|

1841 |

3 567 |

3 777 |

144 |

|

1842 |

3 122 |

3 672 |

88 |

|

1843 |

2 986 |

3 500 |

165 |

|

1844 |

3 560 |

3 955 |

56 |

|

1845 |

2 744 |

4 127 |

77 |

|

1846 |

3 087 |

5 565 |

84 |

|

1847 |

3 213 |

4 452 |

49 |

|

1848 |

3 122 |

3 483 |

39 |

|

1849 |

3 980 |

4 221 |

53 |

|

1850 |

4 534 |

5 534 |

53 |

|

1851 |

4 267 |

4 592 |

39 |

|

1852 |

3 777 |

6 293 |

60 |

|

1853 |

4 568 |

3 833 |

35 |

|

1854 |

4 291 |

6 188 |

32 |

|

1855 |

4 046 |

4 767 |

46 |

|

1856 |

4 526 |

3 017 |

67 |

|

1857 |

6 650 |

4 879 |

39 |

|

1858 |

7 833 |

3 934 |

123 |

|

1859 |

9 657 |

3 780 |

84 |

|

1860 |

9 335 |

4 204 |

49 |

Fig. 4. Russian exports of cotton fabrics to Asia (1831–1860).

Based on: [Gosudarstvennaya vneshnyaya torgovlya v raznykh ee vidakh, za 1831–1860 gg., 1832–1861]

When Russian cotton fabrics were exported to Persia in the 19th century, Armenian merchants undertook the role of intermediaries as they had been in other areas of trade between the two countries since the 16th century. Armenian merchants engaged not only in the trade between Russia and Persia, but also controlled the commercial network in the sphere of Persian commerce. Before going any further, it is important to first explain the history of how Armenian merchants were involved in the trade with Russia.

Armenian merchants had been engaged in trade in the sphere of Persian commerce for a long time. Since the 16th century, Armenian merchants kept distant trade in the city of Jolfer near the Alas River between Azerbaijan and Georgia [Gamo, 1957. P. 170]. In those days, 12,000 Armenian people lived in Jolfer and the city prospered as the biggest commercial center in Persia. During the

Safavid dynasty, Persia first declared Tabriz as the capital. However, as the city was considered to be strategically badly positioned in relation to the political effect of the Osman Empire, Abbas I transferred the capital from Tabriz to Kazvin. He then went on to transfer the capital again, this time from Kazvin to Isfahan in 1598 [Ibid. P. 156]. In 1604, he built the New Julfā – the settlement for Armenian people near Isfahan. When Armenian people settled in New Julfā, Abbas I then transferred the commercial base of the Persian Empire to New Julfā [The Armenians, 1998. P. 3]. At that time, the commercial sphere of Armenian merchants spread from the Caspian Sea through Holasan to Central Asia. They formulated their ethnic communities around Armenian churches outside Persia and connected distant cities through the intermediary network of churches. These conditions brought on the prosperity of Persian trade with foreign countries [Payaslian, 2007. P. 107].

Trade between Russia and Persia began in the 16th century. Since this period, Russia strategically used Persian-Armenian merchants as intermediaries of trade with Persia. In fact, Ivan IV gave Armenian merchants the right to act freely on Russian territory and declared various special treatment for them. Armenian merchants therefore undertook the serious responsibility of conducting trade between Russia and Persia [The Armenians, 1998. P. 37]. Aleksei Mikhailovich also followed Russia’s previous policy [Burton, 1997. P. 292] and admitted not only special trade treatments between Russia and Persia to Persian merchants, but also the establishment of Armenian churches in Russia in 1667. Armenian merchants gradually occupied the dominant position among other merchants operating in Russia. At the time, Persian silk was the most important goods which Armenian merchants were trading and it was in high demand not only in Russia, but also in Northern Europe. However, in the 17th century, the trade route between Northern Europe and Asia had not yet been established. It was only after Sweden had concluded a trade treaty with Armenian merchants when it was able to import Persian silk thorough Russia [The Armenians, 1998. P. 44].

When Afghan occupied Persia’s capital Isfahan in 1722, Safavid Persia came to an end. The Qajar dynasty appeared straight after in 1796, which governed Persia for the next 150 years. As internal political disturbances frequently happened during the period of this dynasty, many Armenian merchants emigrated from Persia to neighboring countries including Georgia, Russia and the Caucasus, in order to flee from the difficult situations surrounding Persia [Payaslian, 2007. P. 109].

Georgia was annexed by Russia after the sovereignty of Georgia was completely entrusted to Russia in 1801 [Nishi Asia shi, 1987. P. 293]. While Russia wanted to expand its territory, Persia wanted to keep its previous territory. As tensions between Russia and Persia heightened, two wars ensued in the first half of the 19th century [Nishi Asia shi, 2002. P. 339]. After the first war (1804– 1813) ended, The Treaty of Gulistan was concluded between Russia and Persia. Persia ceded part of its territory to Russia, including Baku, and admitted Russian sovereignty to Georgia and Dagestan. After the second war (1826–1828), the Treaty of Turkmenchay was concluded between Russia and Persia in 1828 where the two sides drew a border line between the Caucasus and Alas River. Based on the treaty, the one region where Armenian people previously lived together, was divided into the Russian Caucasus and Persian Azerbaijan region [Nishi Asia shi, 1987. P. 293].

This new border did not end the social connection of the Armenian people. The commercial network of Armenian merchants functioned as before across borders, and continued to promote trade between Russia and Persia [The Armenians, 1998. P. 58]. When Russia annexed the Northern Caucasus region, it accepted 45,000 Armenian people from Persia and established an Armenian settlement [Ibid. P. 61]. Though the effect of the Persian and Osman Empire greatly influenced the Caucasus region, Russia influenced this region much more after 1828 [Payaslian, 2007. P. 112]. In 1844, the settlement for Armenian people in Russia moved to Tiflis; present capital Tbilisi of Georgia. The city of Tiflis was the base of Russian–Armenian people and played an important role for trade between Russia and Persia in the 19th century.

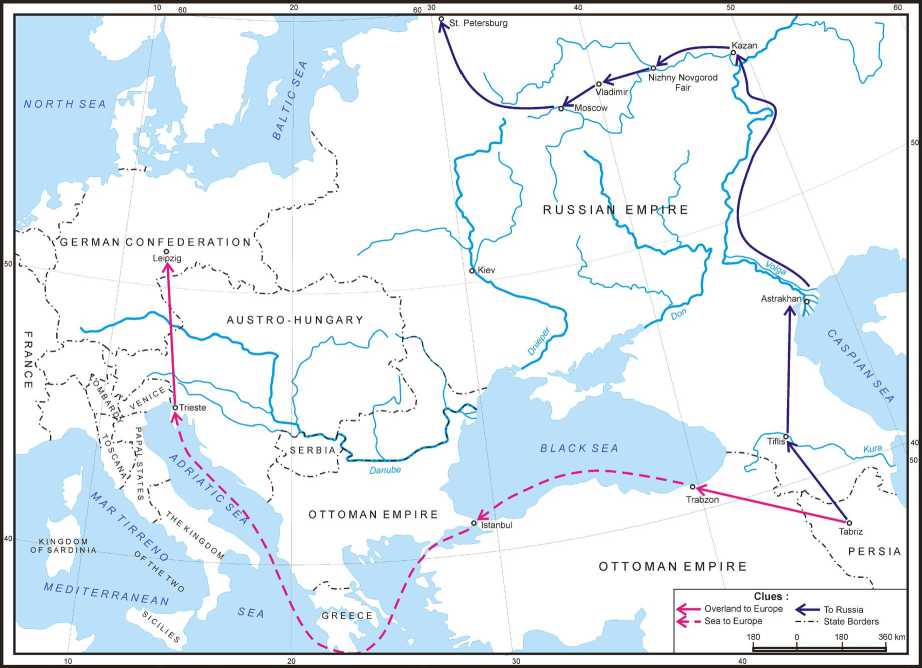

When trade between Russia and Persia was being carried out in the 19th century, Tiflis was the base of domestic distribution in Russia [Panossian, 2006. P. 86], and Tabriz was the base of domestic distribution in Persia (Kommercheskaya gazeta. 1841. Mar. 27. No. 37. P. 146). In those days, Tabriz was an international trade city. Not only Russian goods, but also foreign goods from the Osman Empire and Europe accumulated in this city. Russian–Armenian merchants who lived in Tiflis often visited Tabriz, promoting the trade between Russia and Persia. Prior to the railroad being built in this region, the main means of transportation were camels and mules [Papazian, 1979. P. 16]. Armenian merchants utilized the two kinds of animals and organized caravans to transport commodities between Persia and Russia (Fig. 5). At that time, the trade route from Moscow to Tiflis, including river transportation took 60–90 days, and the route from Tiflis to Tabriz by caravans would take a further 16–20 days (Kommercheskaya gazeta. 1841. Mar. 27. No. 37. P. 146). As a result, the entire period of transportation of commodities from Moscow to Tabriz was about four months.

Fig. 5. The trade route of Armenian merchants.

The map created by Anastasiya L. Nesterkina (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of SB RAS), based on the author’s data

The Nizhny Novgorod Fair in Russia played an important role in the trade between Russia and Persia. The Fair was an intermediary base of trade commodities, transacted between Russia and Asia [Shiotani, 2009]. The goods exported from Russia to Persia and those imported from Persia to Russia usually went through the Nizhny Novgorod Fair to consumers. In the summer months when trade was carried out, Armenian merchants visited the Nizhny Novgorod Fair to purchase goods from Russia and Central Asia in order to export them to Tabriz. In the 1820s, usual commodities, which were exported from Russia to Persia, were cotton fabrics. Some Armenian merchants who looked for Russian printed cotton samples would visit the Nizhny Novgorod Fair, purchase the same kinds of Russian printed cotton at a cheaper price, and then export them from the Fair to Tabriz going on to receive large profits (Kommercheskaya gazeta. 1834. May 17. No. 59. P. 230). This shows one example of close relations between the Nizhny Novgorod Fair and Russian–Persian trade.

Russia had been engaged in transit trade between Europe and Persia for a long time. It took on a preferential policy for European commodities from the viewpoint of tariffs and promoted transit trade [Russko-iranskaya torgovlya, 1984. P. 8]. Russian–Armenian merchants also visited the Leipzig

Fair every year and bought European goods including European cotton fabrics, and exported them through the Osman Empire to Tabriz. During such trades, European goods traveled via land route from Leipzig to Trieste, then by sea from Trieste through Istanbul to Trabzon, and then on land again from Trabzon to Tabriz (Kommercheskaya gazeta. 1834. Mar. 29. No. 38. P. 150). Armenian merchants exported European cotton fabrics from Leipzig to Tabriz by utilizing this route in 1823 (Ibid. 1830. Dec. 20. No. 102. P. 677).

In the late 1820s, printed cotton exported from Russia to Persia was mainly produced in Moscow and Vladimir (Ibid. 1825. Aug. 12. No. 64. P. 4). It was considered to be of acceptable quality by consumers in Tabriz, selling well as a result. However, after Persian merchants began to export European printed cotton from Istanbul to Tabriz, the market share of European products increased and overtook those of Russia in the Persian markets (Ibid. 1834. Mar. 29. No. 38. P. 150). The European printed cotton designs were somewhat irregular, but vividly printed. Therefore, the consumers in Tabriz, who liked the vivid colors, preferred the European design to those of the Russian goods. Russian and European printed cotton was mainly used as the lining material for women’s clothes (Ibid. 1840. Apr. 2. No. 40. P. 158).

European products dominated the Tabriz market in 1830, causing the sales of Russian products to become stagnant. The following year Russia imposed a 5% protective tariff on transit goods from Europe to Persia through Russia and raised the price of European commodities, as a way to protect Russian products being exported to Persia (Ibid. 1853. May 21. No. 58. P. 230). After the European countries opposed Russia’s protective tariff and started to export through the Osman Empire to Tabriz in order to circumvent the Russian trade route, the amount of Russian transit trade subsequently decreased. As the export of European products to Tabriz was as active as before, the effect of the Russian protective tariff policy was negligible. As European products gradually expelled Russian products in the Persian market, the export of Russian printed cotton to Persia decreased. Russian– Armenian merchants continued to export European printed cotton to Persia, even though the export of Russian printed cotton had decreased.

It is important to note that merchants with Russian nationality did not always carry out their business in the interests of the Russian government. While Armenian merchants with Russian nationality exported printed cotton from Russia to Persia, they also exported European printed cotton from Leipzig to Persia at the same time (Ibid. 1841. Jul. 8. No. 81. P. 315). In the 1830s, European printed cotton competed with Russian printed cotton in the market of Tabriz. When European products tried to expel Russian products from the market, if Armenian merchants has sympathized with the national interests of Russia, they would have supported the export of Russian products, and controlled the export of European products for Persia. However the Armenian merchants continued the export of European products to Persia for their own ethnic interests, to the detriment of Russia’s national interests. Based on this fact, it can be concluded that ethnic merchants with Russian nationality attached greater importance to the interests of their ethnic group than to that of their national interests.

In the trade between Europe and Persia, European commodities were mainly exported from Leipzig to Tabriz, thorough Trabzon. This trade route went across land and partly sea. The late 1840s brought on the next wave of progress – the steamship. Steamships connected Manchester and Istanbul by sea route and made it possible to transport many commodities much quicker than before. As a result, the distribution route between Europe and Persia drastically changed (Ibid. 1847. Nov. 25. No. 139. P. 559). After many cheap English commodities were exported to Istanbul by steamship, they would then go on to be transported from Istanbul to the Tabriz market. It is interesting to note that it was Greek merchants with Russian nationality that seemed to largely engage in the trade between England and Istanbul. They exported English products to the Osman Empire and Persia as agencies of English companies [Russko-iranskaya torgovlya, 1984. P. 144]. As Armenian merchants with Russian nationality exported the European printed cotton from Europe to Persia, the Greek merchants with Russian nationality exported English printed cotton products from England to Persia, and European printed cotton competed with English products in the Tabriz market.

Although both Armenian and Greek merchants had Russian nationality, they chose not to cooperate because of their shared roots, and instead compete with each other. Greek merchants with Russian nationality did not pay attention to Russian national interests, and strove to export English products to the Osman Empire and Persia as agencies of English companies. They promoted trade solely in the interests of their ethnic group. Such were the ethics of ethnic merchants in the Russian Empire. The competency of the transportation methods of European commodities exported on land routes from Europe to Persia was inferior to the transportation by steamship from the viewpoint of price and speed. As a result, European trade which Armenian merchants were engaged in became stagnant. Therefore, they chose to specialize in trade between Persia and Russia instead.

The introduction of steamships transferred the bulk of European trade from land to sea routes, however the Armenian merchants who were superior in the comparative land trade chose not to enter sea trade by steamship like the Greek merchants (Kommercheskaya gazeta. 1849. Jul. 19. No. 84. P. 334). Greek merchants also specialized in sea trade, based in Istanbul and Odessa, and hardly engaged in land trade between Russia and Persia [Russko-iranskaya torgovlya, 1984. P. 143]. Although the export of Russian cotton fabrics to Persia decreased after the 1830s, trade between Russia and Persia itself did not decline, keeping up a certain level of trade. Up until the railroad between Moscow and the Caucasus region was built in the first half of the 20th century, the caravans of Armenian merchants supported the trade between Russia and Persia. Armenian merchants continued to keep their superiority in trade between both countries via land routes.

As examined in this article, Asian merchants assumed the trade between Russia and Asia between the 18th – 19th centuries. At the turn of the century, country territories also expanded and contracted on the Eurasian continent, and furthermore some countries which people belonged to also changed. Armenian and Bukharan merchants must have had strong allegiance to their ethnic groups rather than to their countries. This allegiance to their sense of belonging to ethnic groups became the key factor in promoting international commerce. As the concept of a «nation» was still not realized in Russia in the 19th century, Russian people did not share the concept of being a «Russian nation» [Mironov, 1999. P. 63]. Therefore, religion and ethnicity were the key basis for people, and communication proceeded between groups which shared religion and ethnicity. Such was the commercial base for Asian merchants. They easily operated businesses across country borders. As examined previously within trade between Russia and Persia, the interests of ethnic groups sometimes were opposed to that of government.

When Russia promoted trade with Asian regions, it used the commercial network in the neighboring sphere of commerce. Armenian merchants controlled the internal and external commercial network in the sphere of Persian commerce. Bukharan merchants controlled the network in the sphere of commerce in Central Asia. Every Asian merchant occupied a dominant position in Russia’s neighboring spheres of commerce. It was no wonder that each Asian merchant played an important role in Russia’s trade with Asia. Armenian merchants were familiar with the distribution and financial transactions within the sphere of Persian commerce. Historically the Persian shar (king) would utilize them, when promoting trade [Payaslian, 2007. P. 107]. Bukharan merchants controlled the central section of the Silk Road trade in Central Asia, and developed trade with not only Russia, but also Eurasian countries including China and India [Potanin, 1868. P. 3].

The 19th century in Russia was the period when human society departed from the conditions of depending on their natural environment. It would be true to say in other words that sources of power were shifted from natural energy such as power of wind and water, and animal power such as horse and camel, to fossil fuel such as coal. When dividing 19th century Russia into two periods, sources of power were shifted in the field of production from natural energy and animal power to fossil fuel in the first half of the 19th century. If we use the cotton industry as an example, after the steam engine was introduced in the field of production, including the process of printing, spinning and weaving in turn, the sources of power shifted from natural energy and animal power to fossil fuels, and mass production of cotton fabrics was realized. On the other side, a similar shift occurred in the field of distribution in the second half of the 19th century. That is to say that the steam engine used in railway and steamship transport was introduced in the field of distribution. After sources of power were shifted from natural energy and animal power to fossil fuel, mass and speedy transportation was realized. It is not difficult to imagine that this trend of transformation radically changed Russian trade with Asia and greatly influenced the commercial network of Asian merchants.

Список литературы The export of Russian cotton fabrics and the commercial network of Asian merchants in the first half of the 19th century. Part 1

- Arima T. Roshia Kogyoshi Kenkyu . Tokyo, Tokyo Univ. Press, 1973, 335 p. (In Jap.)

- Bogoroditskaya N. A. Nizhegorodskaya yarmarka -krupneishii tsentr vnutrennei i mezhdunarodnoi torgovli v pervoi polovine XIX v. . Gorky, Gor'kovskii gosudarstvennyi universitet, 1989, 71 p. (In Russ.)

- Brokgauz F. A., Efron I. A. Rossiya: entsiklopedicheskii slovar' . Leningrad, Lenizdat Publ., 1991, 922 p. (In Russ.)

- Burton A. The Bukharans: a Dynastic, Diplomatic and Commercial History, 1550-1702. Richmond, Curzon, 1997, 664 p.

- Gamo R. Iran Shi . Tokyo, Shudosha, 1957, 301 p. (In Jap.)

- Mironov B. N. Sotsial'naya istoriya Rossii perioda imperii (XVIII -nachalo XX v.) . St. Petersburg, Dmitrii Bulanin, 1999, vol, 1, 548 p. (In Russ.)

- Mironov B. N. Vnutrennii rynok Rossii vo vtoroi polovine XVIII -pervoi polovine XIX v. . Leningrad, Nauka, 1981, 257 p. (In Russ.)

- Nishi Asia Shi . S. Maejima (ed.). Sekai Kakkoku shi 11. Tokyo, Yamakawa shuppansha, 1987, 594 p. (In Jap.)

- Nishi Asia Shi . Y. Nagata (ed.). Tokyo, Yamakawa shuppansha, 2002, vol. 2, 476 p. (In Jap.)

- Panossian R. The Armenians: from Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York, Columbia Univ. Press, 2006, 492 p.

- Papazian K. S. Merchants from Ararat: a Brief Survey of Armenian Trade through the Ages. New York, Ararat Press, 1979, 56 p.

- Payaslian S. The History of Armenia: from the Origins to the Present. New York, Macmillan, 2007, 296 p.

- Potanin G. N. O karavannoi torgovle s Dzhungaskoi Bukhariei v XVIII stoletii . Moscow, Universitetskaya tipografiya, 1868, 93 p. (In Russ.)

- Shiotani M. Strukturnoe izmenenie assortimenta tovarov na Nizhegorodskoi yarmarke s 1828 po 1860 g. . Gumanitarnye issledovaniya Vnutrennei Azii , Ulan-Ude, 2009, no. 4-5, p. 70-88. (In Russ.)

- Shoji R. Menka . Osaka, Nihon Boseki Kenkyu-jo, 1938, 596 p. (In Jap.)

- Yatsunsky V. K. Krupnaya promyshlennost' Rossii v 1790-1860 gg. . Ocherki ekonomicheskoi istorii Rossii pervoi poloviny XIX v. . Moscow, 1959, p. 118-220. (In Russ.)