The Greenwich meridian of finance: London’s struggle to maintain its role in the global banking (1970s - early 2020s)

Автор: Nikitin L.V.

Журнал: Вестник Пермского университета. История @histvestnik

Рубрика: Экономическая история новейшего времени

Статья в выпуске: 2 (65), 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article analyzes the development of London as a world and national banking centre over the past 50 years, from the early 1970s to the present. The study is based on large arrays of historical statistics, systematized and processed by the author. London was the largest banking centre in the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but it gradually lost its position thereafter; by 1970, it was at third place in the global hierarchy. New factors that emerged in the 1970s (for example, the crisis of the Bretton Woods monetary system) contributed to the further decline of London. At the next historical stage, the situation changed radically as a result of the deregulation of the national financial system, implemented by the Conservative governments of Thatcher and Major (1979-1997) and then Blair's New Labour (1997-2007). Taking advantage of new business freedoms, British banks significantly expanded the scope and directions of their activities. In 2008, London ranked second in the world in terms of banking assets. However, this was largely the result of overproducing risky financial instruments. The British banking system suffered a severe downturn during the Great Recession of 2008-2009. Nevertheless, the main problems were then concentrated not in London, where banks remained relatively stable, but in Edinburgh. Later, London-based corporations led the recovery of the national banking system. London, which has long lost its absolute leadership, still remains a very important financial hub and is undoubtedly one of the five or six largest banking centres in the world.

United kingdom, london, banks, 1970s - early 2020s, competition, rankings, economic policy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147246532

IDR: 147246532 | УДК: 94(410):336.7 | DOI: 10.17072/2219-3111-2024-2-181-193

Текст научной статьи The Greenwich meridian of finance: London’s struggle to maintain its role in the global banking (1970s - early 2020s)

Even among the elite circle of the "capitals of capital" (using the famous phrase of Youssef Cassis [ Cassis , 2006]) London has a special place historically and currently. Some cities gained a lot of influence in international finance long before London (for example, Genoa and Antwerp), but today their importance has dwindled. Other cities, on the contrary, now play a huge role (Tokyo, Shanghai, etc.), but their biographies as global financial nodes are not as long as the biography of London. Early financial institutions of some international importance emerged in the capital city of the Kingdom of England during the 16th and 17th centuries. Later, the establishment of the Bank of England (one of the earliest central banks in the world) in 1694 and some other initiatives triggered the phenomenon of the financial revolution – the formation and outstanding growth of debt instruments (public and private) and the stock market. As the main trends of the 18th and 19th centuries developed (the industrial revolution, the growth of the overseas trade of the United Kingdom, the expansion of the British Empire), London turned into the largest banking, exchange and insurance hub in the world. Just as the meridian of the London-based Greenwich Royal Observatory was widely accepted since the 1880s as

the starting point for geographical measurements, London itself in many ways was the starting point for global capital markets.

However, several decades later, the situation changed dramatically. The rise of New York after the World War I and its predominance after the World War II coincided with the transformation and, ultimately, disintegration of the British Empire (especially intensive in the second half of the 1940s – early 1960s). Even under these circumstances, London was strong and adaptive. Thanks to its extensive business background and the production of innovative financial instruments such as Eurobonds, London retained its leadership on the East Side of the Atlantic, but was nevertheless behind New York (at least in banking, if not the entire financial industry). Towards the end of the 1960s, with a general slowdown in the national economy and the weakness of the pound, the prospects for London looked less and less encouraging.

This article is focused on subsequent events from the early 1970s to the present, which are considered primarily through statistics. It should be noted that the financial industry as a whole, with all its various segments, is not a very convenient object for representation on a single quantitative scale. Several rating projects aim for this goal, but they, for example, greatly underestimate the dominance of the largest financial centres, including London [ Haberly , Wójcik , 2022, p. 135]. However, the situation changes if a researcher confines himself to a single, but very important financial subdivision, namely the banking sector. Such filtration enables us to examine still the enormous business sector (with trillions of dollars in assets), while making accurate and continuous measurements.

For this study, the key source of background information is the annual statistical summaries of the largest banks in the world, which have been published since 1970 by the British magazine The Banker (The Banker Database…). However, the choice of the first half of the 1970s as a starting point is not only related to data availability. There were fundamental shifts in the world economy (the crisis of the Bretton Woods monetary system, failures in the Keynesian model of regulation, oil shocks) in this period, which also had a great impact on the banking. The Banker 's vast databases, as well as other quantitative and non-quantitative sources of information, make it possible to trace, with high accuracy and reliability, how London's place in the global banking system has changed over the course of more than five decades.

The 1970s: the further downfall

In 1970, as calculations show, London ranked as the third largest banking centre in the world. The total assets of the banking cluster on the Thames River were about 60 billion of US dollars, or 7.1 % of the total global volume1. London lagged not only behind New York (106 billion; 12.6 %), which by this time faced its difficulties too, but also behind the rising financial star – Tokyo (72 billion; 8.6 %).

The leading positions in the credit community of London were occupied by the Big Four: Barclays Bank , Lloyds Bank , Midland Bank , and National Westminster Bank . Each of these corporations developed as a result of a long chain of mergers and acquisitions in the capital city and the province. The most recent at that time was the foundation of National Westminster Bank ( NatWest ) in 1968 as the result of the merger of Westminster Bank and National Provincial Bank (turning the former Big Five into the Big Four).

In addition, London was the control centre for a number of banks with a limited presence in the UK itself, but with huge overseas interests. The structure of these financial institutions reflected the history and geography of the colossal British Empire, as well as its even larger commercial ties. Historically, this cluster included Standard Chartered Banking Group (which emerged in 1969 as the result of the merger of The Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China and Standard Bank of British South Africa, becoming the fifth largest in London), Australia and New Zealand Banking Group, Bank of London and South America, and other corporations. Finally, there was a third group of companies, which included historical investment banks (or merchant banks in traditional British terms) with interests primarily in the stock market: Schroders, Kleinwort Benson Lonsdale, Hill Samuel, et al. By the 1970s, these companies significantly expanded their areas of activity. They often offered classic lending and also actively worked abroad, becoming closer in this sense to overseas banks. In addition to these three (partially overlapping) types of banking corporations, various exchanges, brokerage houses, insurance agencies, consulting firms and other financial institutions operated in London; some of them had a very long history and worldwide influence. The various links that existed between banking and non-banking financial institutions gave both sides additional strength.

However, London's immense banking machine continued to lose its proportionate position.

At the time, commentators increasingly referred to the United Kingdom as the "sick man of Europe". The growth of the British national economy was slow and unstable for a number of reasons (which are still disputable). Possible explanations include insufficient pace of modernization of the outdated technological base, excessive influence of trade unions, high level of defense spending, difficulties associated with the preservation and then collapse of the Empire, etc. (for example: [ Grant , 2002, p. 15–16, 76–81]).

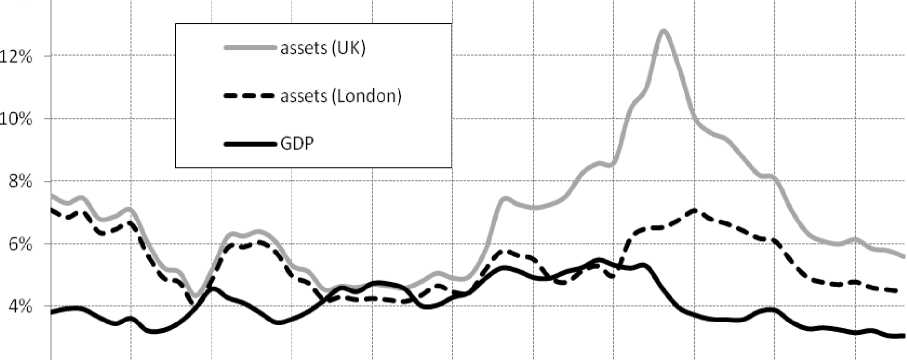

Of course, general problems in the economy led to a weakening of the national currency. Back in 1967, when the post-War Bretton Woods system still maintained fixed rates of some currencies against the US dollar, an inevitable (but controlled and coordinated) devaluation of the pound sterling was carried out [ Schenk , 2010, p. 155–205]. In the next decade, the gradual disintegration of the Bretton Woods mechanisms and their replacement with floating quotations contributed to the further weakening of the British currency. As a result, in the early and mid-1970s the UK's share in both global GDP and global banking assets was declining, and in the latter case, the process was much faster (Figure).

14%

2%

0%

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

Fig. Shares of the United Kingdom and London in world banking assets; share of the United Kingdom in world GDP, 1970–2023

Calculations based on data from:

(The Banker Database…; The UN Statistics…)

The Conservative government of Edward Heath (1970–1974) tried to solve various economic problems, including those in the banking sector, through deregulation. Following this strategy, in 1971 the Bank of England lifted quantitative constraints on lending and introduced some other reforms aimed at liberalizing the industry [ Calomiris , Haber , 2014, p. 143; Capie , 2010, p. 483–523]. Besides, in January 1973, the UK joined the European Economic Community (EEC), and a significant portion of British businesses saw the event as a good opportunity to step up their operations in huge and dynamic markets on the European continent.

Soon the hopes associated with the Heath government gave way to disappointment. The banking reform of 1971 contributed to expansion of lending to an extent, but at the same time it became an additional source of inflation [ Calomiris , Haber , 2014, p. 143–145]. In the autumn of 1973, the Arab-

Israeli War and the Arab oil embargo dealt a new blow to the entire British economy, which by that time continued to import raw hydrocarbons in large volumes. Along with the oil shock and the general economic downturn came the "secondary banking crisis" of 1973–1975. A number of relatively small ("secondary") financial firms heavily involved in mortgage lending and hit by falling property prices narrowly escaped bankruptcy thanks to the costly support from the Bank of England2.

Amidst the recession, the Conservative party lost power after the February 1974 general election. Under the Labour governments of Harold Wilson (1974–1976) and James Callaghan (1976– 1979), the economic situation remained controversial. On the one hand, in the second half of the 1970s the national GDP and the share of the United Kingdom in the world economy grew (partly due to the short-time strengthening of the sterling and the newly-launched oil extraction in the North Sea). On the other hand, this period was marked by a new surge in inflation and the aggravation of various social conflicts, as well as by the relative weakness of London's banking industry (which, of course, is principally important in the context of this study), especially at the end of the decade.

Perhaps the most symbolic case was Australia and New Zealand Banking Group ( ANZ ). During 1976–1977, this bank, which ranked sixth in terms of assets in the UK, transferred its registration from London to Melbourne. ANZ intended to expand its operations globally, so incorporation in Australia made it possible to get around some of the administrative restrictions, which the Bank of England practiced at that time [ Jones , 2001, p. 336]. Thus, for one of the major financial institutions, London ceased to be the centre of its corporate empire.

Of course, the London Big Four banks, which had historical roots on the British Isles, were not going to leave their habitual location. However, these corporations were rapidly losing positions in the global hierarchy. For example, in 1974 Barclays Bank ranked sixth and National Westminster Bank seventh in the world by assets, while in 1979 these corporations dropped to the 19th and 21st places, respectively. Back in 1977, London downgraded to the fifth line in the table of banking metropolises, behind Tokyo, New York, Paris and Frankfurt. The rapid decline in the UK's share of global banking assets contrasted unexpectedly with some increase in the share of global GDP (Figure).

1979–2007: deregulation and rise

A new chapter in the history of the UK was opened after the general election of May 1979, which brought victory to the Conservatives under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher. In 1979–1990, the Thatcher Cabinets moved decisively along the path of wide range economic deregulation, direct tax cuts, privatization, and limiting the power of trade unions.

However, the very first decision under Thatcher on the credit sector had a somehow different logic. The Banking Act, passed in October 1979, expanded the ability of the Bank of England to oversee private financial institutions (basing on lessons of the 1973–1975 crisis) and created a centralized system of deposit protection [ Capie , 2010, p. 629–643].

At the same time, along with the benefits common to all corporations from tax cuts, banks get a number of additional opportunities. Particularly important was the elimination of previous industry barriers, that is, the permission to combine commercial and investment banking as well as specialization in foreign exchange transactions within any large banking corporation. This versatility contributed to the global competitiveness of British banks [ Calomiris , Haber , 2014, p. 147]. Besides, the 1986 reform, commonly known as the Big Bang, introduced looser rules on the London Stock Exchange [ Cassis , 2006, p. 246]. In the same year, the Building Societies Act endowed such companies with many of the functions of classical banks [ Boddy , 1989], and the 1987 Banking Act established important improvements in deposit insurance mechanisms and monitoring practices [ Schooner , Taylor , 1999, p. 632–635].

Not surprisingly, the business-friendly policies of the Thatcher government gave a new energy to British banking corporations. In June 1981, the long-awaited opening of the new National Westminster Bank headquarters was a symbolic beginning of changes. The personal presence of Queen Elizabeth II at the ceremony gave a special significance to the event. The 43-story NatWest Tower was the tallest skyscraper in the United Kingdom for many years (Emporis Building Directory…).

The major British banks (including, of course, National Westminster under the very successful and influential chairman Robert Leigh-Pemberton (1977–1983)3) moved along two directions: the creation of combined corporations with a wide range of financial services and further expansion into foreign markets. For example, in 1979–1983, National Westminster bought and remodeled the National Bank of North America , headquartered in New York City, making this corporation a strategic platform for expansion in the United States ( Bennett , 1983). Meanwhile, a legally autonomous entity called International Westminster Bank was developing large divisions in West Germany, France, and other countries. In 1989, following another typical trend, International Westminster Bank was merged into the multi-functional National Westminster Bank (NatWest Group…).

Nevertheless, in some other cases, transnational activity was not so successful at all. The biggest setback was endured by Barclays Bank and Midland Bank , which had subsidiaries in California since 1965 and 1981, respectively. These banks did not perform well in this market and ultimately sold these branches to San Francisco-based Wells Fargo in the second half of the 1980s [ Pohl , Freitag , 1994, p. 1198, 1224]. In addition, the further development of international business ties meant, of course, the counter movement of foreign financial forces into the UK (for example, the establishment of full control of Deutsche Bank from Frankfurt over Morgan Grenfell Group (London) in 1989 [Ibid., p. 1230]). But in general, the main circumstances of this decade (tax cuts, the abolition of compulsory specialization, and technological progress, especially the spread of ATMs) played in favour of British banks.

Finally, there was another source of inspiration for many companies: the plan announced in 1981–1982 by the Thatcher government to replace the closed docks in the Isle of Dogs and Canary Wharf in the eastern part of London with a new business zone and advanced infrastructure. The construction of the Docklands Light Railway, which began in 1984, was followed by the increasingly active development of office, residential and other projects [ Weinreb et al., 2011, p. 436]. The headquarters of the largest banks at that time still remained in the historic City of London, but the promising area a few miles to the east aroused particular interest among the management of financial corporations.

Thus, throughout the 1980s, London's global share remained rather volatile due to the successes and failures of various corporations, but there was no longer a permanent decline at this stage, unlike in the 1970s (Figure). By 1990, London banks controlled about 4.3 % (840 billion of US dollars) of global banking assets. Under the Japanese banking dominance at the time (see, for example: [ Nikitin , 2022, p. 54–55]), London ranked fourth in the world after Tokyo, Paris and Osaka.

In the early 1990s, the UK experienced a rather long and deep recession along with many other countries. Moreover, due to the difficult economic situation in September 1992, the British government was forced to withdraw the sterling from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) – less than two years after joining this system. Other EU countries continued their historic path to a single currency without the United Kingdom.

Despite these circumstances, as well as the unexpected resignation of Thatcher in November 1990, the British Cabinets showed a clear continuity in most issues of economic policy. Under John Major (1990–1997) Conservative governments remained no less business-friendly than in the previous decade under Margaret Thatcher. It is not surprising that the top managers of many financial companies in London remained generally optimistic and still set themselves big goals.

Rather paradoxically, the source of the most important corporate event in the British banking system of those years was not in London itself, but thousands of miles away. Back in 1865, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation ( HSBC ) was founded in Hong Kong, then under the British rule. From its genesis, HSBC has played an important role in trade relations between China and the United Kingdom. Over time, HSBC has grown into a giant financial player with diverse business interests and a wide presence of offices in Asia, Europe, and North America [ Roberts , Kynaston , 2015, p. 1–6]. In many ways, including the British origins of its top management, HSBC resembled London's overseas banks. However, its headquarters was located not on the Thames River, but near Victoria Harbour in the South China Sea.

Under the new generation of energetic leaders, Michael Sandberg (1977–1986) and William Purves (1986–1998), HSBC firmly established itself among the global banking elite and continued to strive towards new financial heights. Meanwhile, an important political factor began to play an in- creasingly prominent role: the forthcoming transfer of Hong Kong to the jurisdiction of the People's Republic of China, which was agreed upon between London and Beijing in 1984. This event, scheduled for 1997, caused some concern in Hong Kong business circles. On the other hand, the Great Britain under Margaret Thatcher and John Major became more and more attractive as a base for the activities of financial corporations.

HSBC had longstanding and varied interests in London, but now the question arose of a much more decisive reorientation of the company from the Far East to the British capital city. A very important step was taken in 1987 when HSBC bought a large stake in London-headquartered Midland Bank [Ibid., p. 96–97]. What began as a tentative rapprochement between two corporations quickly turned into a mutually beneficial partnership and, finally, into the idea of a merger on the basis of a larger contributor – HSBC . After rather complicated negotiations and a long series of legal procedures, the merger of HSBC and Midland Bank was formalized in 1992. The Bank of England approved the deal, but insisted that the combined financial group be registered in London, not in Hong Kong [Ibid., p. 179]. With certain political risks that were already visible in Hong Kong, this idea could hardly lead to rejection on the part of the corporation's owners and managers. After the merger and relocation, the new HSBC immediately became the largest bank in London (with assets of 258 billion of US dollars in 1993), ahead of longtime leaders Barclays (225 billion) and NatWest (217 billion). Later, in 1999– 2002, the 45-storey skyscraper was erected for HSBC in the new business district of Canary Wharf (Emporis Building Directory…). Designed by famous architect Sir Norman Foster, this magnificent building became the corporate global headquarters and housed several thousand employees.

In mid-1990s, we can see other ambitious mergers and acquisitions among British financial institutions. Particularly important was the 1995 merger of Lloyds Bank with the TSB Group (the latter has historically been an association of numerous retail banks located in dozens of cities and towns throughout the UK). The new institution, named Lloyds TSB Group , has become Britain's largest retail bank (Lloyds Bank…, 1995), also ranking fourth in terms of total assets (after HSBC , Barclays and NatWest ). It also should be noted that these mergers in Britain ( HSBC – Midland , Lloyds – TSB , and others) were part of a much wider trend. In the 1990s, a series of spectacular banking mergers (associated, in turn, with industry deregulation) were also observed in other countries, including financial giants such as the United States and Japan [ Nikitin , 2019, p. 204–211, 215–219, etc.; Nikitin , 2022, p. 56–57].

Besides these success stories, there was a very different case in the London financial community during this period. The famous Barings Bank , which was founded in 1762 and at one time even had a reputation of the "sixth great power" in European politics, suffered huge losses in 1994–1995 due to the risky actions of one of its traders with Japanese financial instruments and an ineffective internal audit. Finally, after unsuccessful attempts by the Bank of England to save Barings , it was purchased in 1995 by the Dutch ING Group for a nominal sum4. Certainly, the liquidation of a financial institution with such a long and brilliant history was an extraordinary event. But it must be emphasized that long before this drama, Barings gradually transformed from a transnational financial giant into a mediumsized corporation, many times inferior in terms of assets to such contemporary leaders as HSBC or Barclays . Thus, the fall of Barings did not have a significant impact on London's position among the global banking centres.

Meanwhile, the Labour Party, led by Tony Blair, won the general parliamentary election in May 1997. During their 18 years in opposition, Labour gradually began to recognize some of the achievements of Conservative governments of Thatcher and Major. Now in power, New Labour sought to maintain favourable conditions for business in various sectors of the national economy. An important part of this strategy was the decisions adopted in 1997–2001 to expand the autonomy of the Bank of England, as well as to create the Financial Services Authority (FSA) – a single regulator that was gradually entrusted with the supervision of various types of financial institutions [ Andryushin , 2019, p. 71–72], including banks. (Previously, supervision of private banking corporations was carried out by the Bank of England.) Noteworthy, the headquarters of the FSA was located not in the City of London, but in one of the newest buildings in Canary Wharf. As subsequent events showed, the FSA sought to minimize its interference in the activities of private business [ Pavlova , 2020].

The 2000s, like the previous decade, were a time of great mergers, although not always in favour of London.

By the end of the 1990s, NatWest (then the third largest bank in London and the whole of the UK) was going through a long series of hardships, mainly due to the mistakes made by management. NatWest ’s stock plummeted, which in turn made possible for a smaller competitor, Edinburgh-based Royal Bank of Scotland (with assets of 146 billion of US dollars at the beginning of 2000), to acquire this huge financial institution (287 billion). The enlarged Royal Bank of Scotland ( RBS ) continued to use the NatWest brand for some of its divisions. Nevertheless, the headquarters of RBS , contrary to many expectations, did not move to London, but remained in Edinburgh [ Martin , 2013, p. 91–105].

Besides, in 2004 Abbey National (the fourth largest bank in London at the moment, as well as one of the former building societies) was acquired by the Spanish Banco Santander ( Timmons , 2004); such cross-border mergers were becoming more common for nations of the European Union.

The liquidation of NatWest and Abbey National as independent financial entities significantly slowed the growth of London's overall banking performance in the first half of the decade. However, the contribution of other corporations was sufficient to ensure that London's share in global banking during this period remained fairly stable, and later (since 2005) its share began to grow again (Figure). The most active bank in that period was Barclays under its new CEO John Varley. A series of decisive moves (for example, the purchase of a large stake in Absa , a big financial group in South Africa, in 2005 ( Spikes , Macmillan , 2005)) soon made the corporation the largest bank by assets in the world. The fact that a British bank achieved such heights for the first time in many decades (after the almost uninterrupted dominance of first American and then Japanese corporations) was remarkable. Also in 2005, a new chapter in Barclays ' development began with the transfer of its headquarters from Lombard Street, in the historic City of London, to the recently built 32-story skyscraper in Canary Wharf (Emporis Building Directory…).

Along with the achievements of the private sector, the financial significance of London was confirmed when a new structure for the monitoring of banking activities throughout the EU, the Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS), was placed there in 2004.

By the beginning of 2008, the London banking cluster, headed by a somewhat different group of leaders ( Barclays , HSBC , Lloyds TSB ), accounted for 6.5 % of global assets (5.8 trillion of US dollars), which put the capital city of the UK in second place in the world, behind only Paris. At the same time, the aggregated number of wholesale financial services jobs (not just banking) in London reached a new record high [ Cassis , Wójcik , 2018, p. 39–41]. The financial community on the Thames River was very active in exploiting the opportunities of further deregulation under the New Labour Cabinets of Tony Blair (1997–2007).

From 2008 to the present days: the Great Recession and beyond

However, while Barclays and some other banks were performing spectacularly, very dangerous and destructive mechanisms were already at work in the British financial system. In the 2000s, the United Kingdom (alongside the United States, Ireland, Spain, and several other countries) saw a real estate sales and construction boom. This was accompanied by an unprecedented rise in mortgage lending, including subprime mortgages for clients with low and moderate incomes. Additionally, new and highly sophisticated financial instruments designed to redistribute and mitigate credit risk had become widespread. Various types of financial companies participated in this multilevel game. Along with investment funds, insurance groups, rating agencies and other actors, banks made a significant contribution to the formation of the real estate bubble.

Some years before the crisis, at least two basic indicators in British statistics pointed to serious problems ahead.

First, the country returned to a steady excess of total banking assets over GDP. A similar situation had been previously observed, but it had been many years prior (in the 1970s and early 1980s), and with a less pronounced imbalance (Figure).

Secondly, the ratio of banks' own capital to the volume of assets sharply decreased in the UK after 2005. In this case, as in the previous one, it is useful to look at a more distant retrospective. In the

1970s, the ratio of capital to assets of British banks was in the safe and comfortable range of 5–6 %, which was well above the global average of 4 %. Later, after some fluctuations, these ratios closely converged. From the first half of the 1990s to the mid-2000s in both cases they were about 4.5 %. In 2005, these trajectories began to diverge again, but now the situation had reversed in comparison with the previous gaps in the 1970s: the global average remained close to 4.5 %, while in the UK the ratio fell to dangerous levels of around 3 % in 2008–20095. British banks, which were very reliable some decades ago, now practiced exceedingly rapid increases in assets (including through the expansion of subprime mortgages), and this generated serious threats if low-income clients had difficulty repaying loans. Such problems became particularly evident in September 2007, when Northern Rock (a fairly large bank based in Newcastle upon Tyne) experienced a dramatic flight of depositors earlier than other financial institutions during this crisis [ Shin , 2009].

However, important differences within the UK should be noted too. The most active sources of high-risk loans were located outside London. First, it was the Edinburgh-headquartered RBS , which under CEO Fred Goodwin gained phenomenal speed and became the world leader in terms of assets in 2008. Secondly, a similar role (on a somewhat smaller scale) was played by HBOS , also registered in Edinburgh6. On the Figure we can see that the main contribution to the potentially dangerous excess of total assets over GDP was made by non-London corporations.

When the major wave of the financial crisis came in September 2008, the Labour government of Gordon Brown (2007–2010) had to deal primarily with the problems of Scottish banking institutions. The government bailed out RBS at great expense and bought out the bulk of the company' shares [ Martin , 2013, p. 271–280]. Scottish HBOS and the London-based Lloyds TSB also received assistance. Lloyds TSB was overburdened with subprime mortgages, but not to the same extent as its competitors from the north. After rather heated discussions, the government and private shareholders decided to merge Lloyds TSB and HBOS ( Carrell , 2008). The combined and partially nationalized corporation, headquartered in Gresham Street in the City of London, was named Lloyds Banking Group .

Meanwhile, the two largest London banks ( Barclays and HSBC ) were also hit hard by the overproduction of subprime mortgages and related financial instruments. However, thanks to more cautious financial tactics in the pre-crisis period, the situation in these companies was not as bad as in Lloyds , not to mention Scottish banks. Due to their relative stability, Barclays and HSBC contributed to the gradual recovery of the national banking system.

Some time later, the government adopted new anti-crisis measures. While under the Brown Cabinet in 2007–2009 urgent solutions were needed to save troubled corporations, the coalition (Conservative–Liberal Democrat) government of David Cameron and Nick Clegg (2010–2015) was able to implement systemic reform of the financial sector in relatively calm conditions. Important laws were passed in 2012–2013, including the abolition of the Financial Services Authority (FSA). This macroregulator created under the Labour rule in the late 1990s – early 2000s has since been criticized for being unprofessional and too loyal to the risky strategies of various financial companies. In 2012, the functions of the former FSA were divided between two new institutions – the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The monitoring of the bank activities was entrusted mainly to the PRA. Unlike the FSA, the PRA began to work very closely with the Bank of England, and also consistently ensured that private companies strictly adhered to key norms. British laws of 2012–2013 (as well as, for example, the Dodd–Frank Act of 2010 in the United States) have become an important part of a broad international trend of increased financial supervision, compared to the practice of previous decades [ Pavlova , 2021]. There is no doubt that the reforms introduced by the Cameron– Clegg government played a significant role in stabilizing many financial services in the UK.

In general, the following years saw the recovery of the national banking system of Great Britain. However, certain old problems remained and new ones emerged. A remarkable example is the fate of a very important international institution. In place of the Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS), founded, as already noted, in 2004 and headquartered in London, the EU established the European Banking Authority (EBA) in 2011. Despite the recent banking turmoil in the UK, it seemed logical that the European Commission decided to place the EBA in London as well (this time not in the City of London, where CEBS was based, but in Canary Wharf). However, the situation changed dramatically when the majority of Britons voted for the withdrawal of their country from the EU in a referendum in June 2016. Although there were still heated debates around Brexit for quite a long time after, and the decision to withdraw did not yet seem final, EU authorities preferred to remove the EBA from London to the Continent in advance. After a thorough consideration of the issue, in 2017 the choice was made in favour of Paris (Ewing, Castle, 2017; Noonan, 2017). In 2019, with the final relocation of the EBA, Paris and its La Défense business district gained an important additional advantage over London and Canary Wharf.

The situation in the private banking sector was also ambiguous. Undoubtedly, the conclusion of the phased sale of Lloyds ’ shares (previously owned by the government) in 2017 was a positive movement ( Treanor , 2017). This meant that the corporation had, on the whole, overcome the consequences of the 2007–2009 crisis and no longer needed special assistance. HSBC also performed well. Once again the largest bank in the UK since 2010, it continues to hold this position. These achievements were accompanied by a major restructuring of international activities. For example, HSBC stepped up its ties with mainland China, but abandoned a number of inefficient destinations in Latin America [ Roberts , Kynaston , 2015, p. 653–655]. Barclays , on the contrary, decreased somewhat in rank, but this did not prevent it from maintaining a reputation as a powerful and generally reliable business.

These and many other individual cases form the following generalized picture. In 2023, London ranked fifth among the banking metropolises of the world at 6.8 trillion of US dollars (4.5 % of global assets), after Beijing, Paris, Tokyo, and New York. Although this seems a relatively low position at first glance, this is quite impressive given that after 2008 there was a powerful offensive by Asian (especially Chinese) banking centres, while European contestants continued to decline (with Paris and London as rare and partial exceptions).

In the 2010s and early 2020s, the share of British (including London-based) banks in global total assets has been gradually declining, somewhat faster than the national economy’s share of world GDP (we must also note here the depreciation of the sterling against the US dollar that occurred in the middle of the former decade). This also meant that the UK generally overcame the huge and dangerous excess of assets over GDP observed on the eve of the 2008 crisis (Figure). The capital-to-assets ratio of London banks is 4.5 %, which is below the current global average of 6.7 %, but above the risky values (about 3 %) that prevailed in the UK by the beginning of the Great Recession. In short, some decline of London from its previous global positions was accompanied by financial normalization (recall again that even in 2008–2009 the situation in London banks was not as difficult as that of their Scottish competitors).

Of course, over the half century discussed in this article, much has changed in the banking sector both in London itself and across the globe. From having the third highest assets in 1970, London moved to fifth position in the early 2020s. In place of the Big Four of the late 1960s ( Barclays , Lloyds , Midland, and NatWest ), London is now dominated by the new Big Three ( HSBC , Barclays , and Lloyds ), alongside which many other banks ( Standard Chartered , Schroders, etc.) also operate. Two of the three named corporations ( HSBC and Barclays ) settled in the new business district of Canary Wharf, less than one mile from the Greenwich meridian and not far from the Royal Observatory on the opposite bank of the Thames. Thus, the reference to the Greenwich meridian used in the title of this article has taken on an even more literal meaning. London banks (above all, of course, the current Big Three) remain corporations with large transnational connections and interests. The logos of these companies ( HSBC 's red and white hexagon, Barclays ' gradient blue eagle, and Lloyds ' black horse) are well recognizable not only within the UK, but across the world. The top managers of these corporations (respectively, Noel Quinn, Coimbatore Venkatakrishnan (“Venkat”), and Charles Nunn) are in the highest strata of the global financial elite.

The world economy continues to change rapidly, constantly, and unpredictably. It will take some time to estimate with sufficient accuracy the long term impact that the major challenges of the early 2020s (like Brexit, formalized in February 2020 under the Conservative government of Boris Johnson (2019–2022); the recent coronavirus pandemic, including closely related lockdowns and inflation; and the latest turmoil in the cryptocurrency markets) will have on London's international banking status. But in any case, we can say with confidence that London will remain one of the most im- portant banking hubs on the planet, bringing this very important mission, which started more than 300 years ago, into the 21st century.

Endnotes

-

1 Here and further in this article, the absolute, share, or rank indicators of countries, cities, and corporations in the banking sector are drawn from processed initial data of The Banker . Following the standards of The Banker database, the author uses values not in British pounds, but in US dollars. The absolute numbers, as in The Banker , are quoted at current prices and are based on the market rate of the dollar.

-

1 This crisis, including its international aspects, has been studied in detail by Margaret Reid, Forrest Capie, and Catharine R. Schenk [ Reid , 1982; Capie , 2010, p. 524–586; Schenk , 2014].

-

1 Later, from 1983 to 1993, Leigh-Pemberton served as Governor of the Bank of England.

1 The story of the collapse of Barings Bank has been detailed in several books and articles, for example: [ Drummond , 2009].

1 As with assets, information about the capital of banks, as well as its ratio to assets, is given by the results of calculations based on the initial data of The Banker .

1 HBOS was created in 2001 as a result of merger between Bank of Scotland (Edinburgh) and Halifax plc from Northern England.

Primary sources

Bennett, R. (1983), “NatWest Does the Unexpected”, The New York Times , 18 Sept.

Carrell, S. (2008), “Lloyds TSB Shareholders Back HBOS Merger”, The Guardian , 19 Nov.

Emporis Building Directory. United Kingdom. London , available at:

(accessed: 15.12.2021).

Ewing, J. & S. Castle (2017), “Key European Agencies Move to Continent, Signs of Brexit’s Toll”, The New York Times , 20 Nov.

“Lloyds Bank to Merge with TSB Group” (1995), The New York Times , 12 Oct.

NatWest Group. International Westminster Bank Ltd. Brief History, available at: (accessed: 26.05.2023).

Noonan, L. (2017), “EBA Shift Expected to Weaken UK Role in Regulation”, The Financial Times , 21 Nov.

Spikes, S. & A. Macmillan (2005), “Barclays to Acquire 60% Stake in South African Lender Absa”, The Wall Street Journal , 10 May.

Timmons, H. (2004), “Deal Gives Banco Santander a Foothold in Britain”, The New York Times , 27 July.

The Banker Database. Top 300/500/1000 World Banks, 1970–2020 , available at:

(accessed: 25.05.2023).

Treanor, J. (2017), “Lloyds Reaches Landmark as Government Sells Final Shares”, The Guardian , 16 May.

The UN Statistics Division. National Accounts Main Aggregates Database, available at: (accessed: 18.06.2023).

Список литературы The Greenwich meridian of finance: London’s struggle to maintain its role in the global banking (1970s - early 2020s)

- Andryushin, S.A. (2019), Denezhno-kreditnye sistemy: ot istokov do kriptovalyuty [Money-Credit Systems: From Sources to Cryptocurrencies], Sam Poligrafist, Moscow, Russia, 452 p.

- Boddy, M. (1989), "Financial Deregulation and UK Housing Finance: Government-Building Societies Relations and the Building Societies Act, 1986", Housing Studies, vol. 4, iss. 2, pp. 92-104.

- Calomiris, C.W. & S.H. Haber (2014), Fragile by Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA, 584 p.

- Capie, F. (2010), The Bank of England: 1950s - 1979, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, 921 p.

- Cassis, Y. (2006), Capitals of Capital. A History of International Financial Centres. 1780-2005, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, 400 p.

- Cassis, Y. & D. Wojcik (eds.) (2018), International Financial Centres after the Global Financial Crisis and Brexit, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 268 p.

- Drummond, H. (2009), The Dynamics of Organizational Collapse: The Case of Barings Bank, Routledge, New York, USA, 159 p.

- Grant, W. (2002), Economic Policy in Britain, Palgrave, New York, USA, 265 p.

- Haberly, D. & D. Wojcik (2022), Sticky Power: Global Financial Networks in the World Economy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 400 p.

- Jones, G. (2001), British Multinational Banking, 1830-1990, Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK, 528 p.

- Martin, I. (2013), Making it Happen: Fred Goodwin, RBS and the Men Who Blew Up the British Economy, Simon & Schuster, London, UK, 361 p.

- Nikitin, L.V. (2019), Prodolzhenie Uoll-Strit: Nyu-York i drugie bankovskie stolitsy SShA na rubezhe XX-XXI vekov [The Greater Wall Street: New York City and Other Banking Metropolises of the USA in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries], Izd -vo YuUrGGPU, Chelyabinsk, Russia, 545 p.

- Nikitin, L.V. (2022), "Financial Storms in the Pacific: the USA-Japan Competition in the Banking Sector (1970-2020)", VestnikPermskogo universiteta. Istoriya, vol. 59, № 4, pp. 51-61.

- Pavlova, O.Yu. (2020), "Banking Reforms of 1997-1998 in the United Kingdom and their Consequences", Rossiyskiy ekonomicheskiy Internet-zhurnal, № 2, p. 42.

- Pavlova, O.Yu. (2021), "Banking Reforms of 2012-2013 in the United Kingdom: First Results", Rossiyskiy ekonomicheskiy Internet-zhurnal, 2021, № 1, p. 13.

- Pohl, M. & S. Freitag (eds.) (1994), Handbook on the History of European Banks, Edward Elgar, Alder-shot, UK, 1328 p.

- Reid, M. (1982), The Secondary Banking Crisis, 1973-75: Its Causes and Course, Macmillan, London, UK, 228 p.

- Roberts, R. & D. Kynaston (2015), The Lion Wakes: a Modern History of HSBC, Profile Books, London, UK, 785 p.

- Schenk, C.R. (2010), The Decline of Sterling: Managing the Retreat of an International Currency, 1945-1992, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 464 p.

- Schenk, C.R. (2014), "Summer in the City: Banking Failures of 1974 and the Development of International Banking Supervision", English Historical Review, vol. 129, iss. 540, pp. 1129-1156.

- Schooner, H.M. & M. Taylor (1999), "Convergence and Competition. The Case of Bank Regulation in Britain and the United States", Michigan Journal of International Law, iss. 4, pp. 595-655.

- Shin, H.S. (2009), "Reflections on Northern Rock: The Bank Run That Heralded the Global Financial Crisis", Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 23, iss. 1, pp. 101-119.

- Weinreb, B., Hibbert, C., Keay J. & J. Keay (2011), The London Encyclopedia, Macmillan, London, UK, 1120 p.