The Horizon of Startups in Algeria in Light of Law 22-18

Автор: Fouzi Z., Hocine H.

Журнал: Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems @imcra

Статья в выпуске: 7 vol.8, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Law 22-18 reflects a genuine desire to effectively boost the national economy. It is a law that provides for no discrimination between private and public investors, nor between Algerian and foreign investors. The investor will deal with a single point of contact: the Investment Promotion Agency (API). Among its new provisions is the creation of the One-Stop Shop, which addresses key areas such as investor expectations and access to land — a matter specifically handled by the One-Stop Shop. There are also obligations for investors who benefit from incentives; they must commit to fulfilling all related obligations. The changes are assessed on two levels: In terms of principles: the freedom to invest, equality between resident and non-resident investors, stability, and speed in the processing of investment applications. On the second level, regarding the advantages granted to investors: the establishment of the non-retroactivity of laws and assurances regarding the transfer of dividends and the repatriation of proceeds from the sale of foreign investments in a straightforward manner.

Foreign investment, foreign exchange, Law 22-18, strategic sectors, tax exemptions

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/16010886

IDR: 16010886 | DOI: 10.56334/sei/8.7.64

Текст научной статьи The Horizon of Startups in Algeria in Light of Law 22-18

-

1. Introduction

Algeria presents tangible opportunities for Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs). The resurgence in the importance of Algeria as a destination since the early 2000s is an undeniable testament to this.

Regarding the remainder, these circumspections commonly constitute an essential minimum threshold, though not always consistently satisfactory. Even if they contribute to diversification, they appear limited. Consequently, this indicates an attractiveness policy guided exclusively towards offering symptomatic territorial advantages, as opposed to an attractiveness policy driven by a resolute offering based on the correlating relationship between territorial characteristics—particularly when they are distinctive—and the characteristics sought by firms 1

-

• The first part will examine the adoption of an active FDI attractiveness policy;

-

• The second part will reveal FDI trends and their effect on the Algerian industrial sector.

-

I. Adoption of a proactive policy for attracting FDI

The implementation of an active attractiveness policy is driven by the actions of the country" perspective, as proposed by L. T. investment promotion agency. From a "marketing a

Wells and A. G. Wint in 2001, the agency's promotional efforts target its specific audience.

Thus, based on the three generations of FDI promotion measures presented by UNCTAD in

:s attractiveness policy is outlined as follows'the current state of Algeria , 2002

Generation Measures-a. First

In these measures, the country adopts a liberal approach, implements a more flexible national ccessfully investment regime, and improves the treatment of foreign investors. Algeria has su pursued this approach with a highly favorable investment code and attractive guarantees for .investors, notably national treatment

Generation Measures-b. Second

-

* Adjunct Faculty Member, University of Algiers 3.

Investments Here, the country progresses to a higher stage, actively attracting Foreign Direct FDIs) by "showcasing the merits" of the country. This approach involves creating an ) investment promotion agency. For investment promotion, Algeria demonstrated its in (commitment by establishing the National Agency for Investment Development (ANDI . 2001

Generation Measures-c. Third

In this stage, the country has already accomplished the two previous approaches and is preparing to target foreign investments by sector and company type. The country seeks to izing export promotion, for example. Taking into fulfill development priorities by emphas account the evolving location strategies of potential firms, the country promotes specific sites .in particular sectors

-

I.2.3. the Question of Free Zones in Algeria

A free zone is an area or "a part of a state's territory" that benefits from tax advantages (exemption from income tax, professional taxes, employer contributions, etc.) and customs benefits (exemption from import and export duties, access to the local market, etc.) for a specified period. These are preceded by a multitude of other advantages aimed at attracting businesses, such as employment flexibility and preferential telecommunications rates. The goals for host countries are to:

-

• Stimulate production and exports;

-

• Acquire skills and resources;

-

• Benefit from job creation and technology transfer, which would lead to economic and

social development.

-

I.3. Industrial Strategy

Algeria now aims to transition from being a mere exporter of primary products to becoming a producer and exporter of transformed goods with more sophisticated technology and high added value. The need to design a new strategy to revive industry emerged within a favorable context of economic stabilization. Furthermore, this return to industry was bolstered by the prior revitalization of agriculture through the National Agricultural and Rural Development Plan (PNDAR).

-

I.4. Construction of Algeria's Attractiveness Matrix

-

I.4.1. Matrix Presentation

-

The attractiveness matrix representation method correlates the effective amounts of realized foreign direct investments (FDI) as per the World Bank (WB) and the potential entry index, calculated by UNCTAD. The objective is to:

-

• Evaluate Algeria's attractiveness performance and its rate of evolution.

-

• Qualify the "Algeria site" in terms of attractiveness across the various phases of development the country has experienced.

-

• Show whether the "Algeria site" can one day be included in investors' "shortlist," or if it remains in the fourth circle, grouping "peripheral countries," whose attractiveness, according to C. A. MICHALET, 1999 (Charles, 1999, p. 135), relies exclusively on the existence of abundant factors such as natural resources (hydrocarbons).

The matrix construction is based on the "potential entry index" (or potentiality index) of foreign direct investments, calculated by UNCTAD since 1988. This index is primarily based on economic and institutional variables. It corresponds to the unweighted average of the normalized values of eight variables for each country. The variables are: GDP per capita, GDP growth rate, export share in GDP, number of telephone lines per 1000 inhabitants, private sector energy consumption per capita, share of public and private R&D expenditure in GDP, percentage of postgraduate students in the total population, and country risk. The choice of variables was based on the results of studies concerning the determinants of FDI (J. H. DUNNING, 1993 (DUNNING, 1993) and UNCTAD, 2002 (UNCTAD, Transnational Corporation and Export Competitiveness, 2002)). This index ranges between 0 and 1. The closer it is to 1, the more attractive the country is considered; the closer it is to 0, the less attractive the country is considered.

-

I.4.2. Advantages of the Attractiveness Matrix

This matrix, structured in zones, is a visualization that helps to schematize Algeria's attractiveness. The analysis is conducted based on the typology of C. A. MICHALET, 1999 (Charles, 1999, p. 135), who delimited the circles according to the attractiveness of the different economies in the study's sample. The attractiveness matrix, based on the potential FDI entry index and the amounts of received flows, is designed to provide greater visibility to public policymakers and analysts on this issue. It aims to measure the country's attractiveness performance and in no way the impact of FDI on the host country's economy.

-

2. Trends in Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) and Their Effects on Algerian Industry

The purpose of the attractiveness matrix is to illustrate the evolution of the country's economic situation by presenting the different zones. The observation concerning Algeria supports the analysis of M. C. MICHALET, 1999 (Charles, 1999, p. 135), according to which the country does not necessarily pass through the different zones successively.

Since its independence, Algeria has consistently aimed to attract FDI flows, a commitment affirmed in various investment laws. Indeed, the country's natural resources, combined with numerous comparative advantages such as proximity to Europe, developed infrastructure, availability of a young workforce, a strong Francophone presence, and tax incentives, are all favorable determinants.

The transition process from a centralized system to a market economy compelled the Algerian government to implement structural reforms starting in the early 1990s. These reforms facilitated the restoration of macroeconomic balances and the liberalization of the economy. The privatization of public enterprises and the opening to FDIs have been two major pillars of Algeria's economic policy since the early 2000s. While Algeria has experienced a significant increase in FDI flows in recent years compared to the 1990s, these inflows remain insufficient relative to the country's potential.

-

II .1. Evolution of Foreign Direct Investments in Algeria

A. BOUYACOUB (2007) analyzes the FDI flows received by Algeria, highlighting three major periods based on the movement of these flows:

-

a) The 1973-1979 period: This era saw the opening of the hydrocarbon sector to foreign capital in 1971, particularly in the oil, natural gas, refining, production, and exploration branches.

-

b) The 1980-1995 period: This period was characterized by a near-total absence of FDIs. However, investments in the hydrocarbon sector continued to occur.

-

c) The period after 1996: This began with the new legislation on the privatization of public enterprises (1995) and a more appropriate institutional support framework, introduced by the new investment code of 1993, which was amended in 2001 and 2006.

Therefore, the analysis of FDI evolution in Algeria will be divided into two parts. The first covers the period preceding the structural reforms, while the second covers the period following these reforms, specifically from the 1990s onward. It is worth noting that all reforms undertaken during this period only began to yield results from the 2000s (due to the security situation), a date which coincides with the signing of the association agreement with the European Union.

-

II.1.1 . Evolution of Foreign Direct Investments Before Structural Reforms

Since the opening of the oil and natural gas industry in 1971, Algeria has attracted significant FDI flows into these sectors. It's important to note that almost 100% of investments during this period were concentrated in the hydrocarbon sector. These were heavily invested in the refining, exploration, production, and transportation of hydrocarbons. The attractiveness of this sector increased following the oil shocks of the 1970s and 1980s. The rise in oil prices and the prohibition on major oil groups owning oil fields made investments in oil and gas infrastructure even more appealing. This also helped to offset the lack of financial resources needed for their maintenance and upgrading. Nevertheless, prior to 1992, Algeria did not allow foreign companies to produce directly for their own account.

benefit from production-sharing agreements or other service contracts with the state-owned company Sonatrach

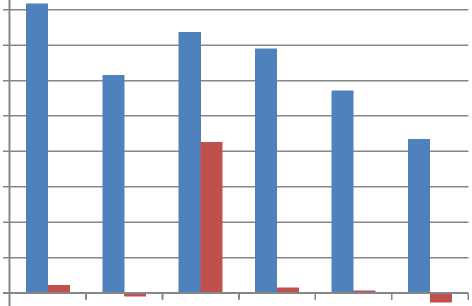

Table 1: FDI Flows in Algeria, 2016-2021.

|

IDE Inflows (in $10^6) |

Startup Exits (in $10^6) |

||||||||||

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

1636 |

1232 |

1475 |

1382 |

1143 |

870 |

46 |

-18 |

854 |

31 |

15 |

-52 |

Source: UNCTAD, FDI/MNE database (.

Figure No. 1: FDI Flows in Algeria, 2016-2021.

-

■ FDI INFLOWS

-

■ FDI OUTFLOWS

-200

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Source: CNUCED, FDI/ MNE database (.

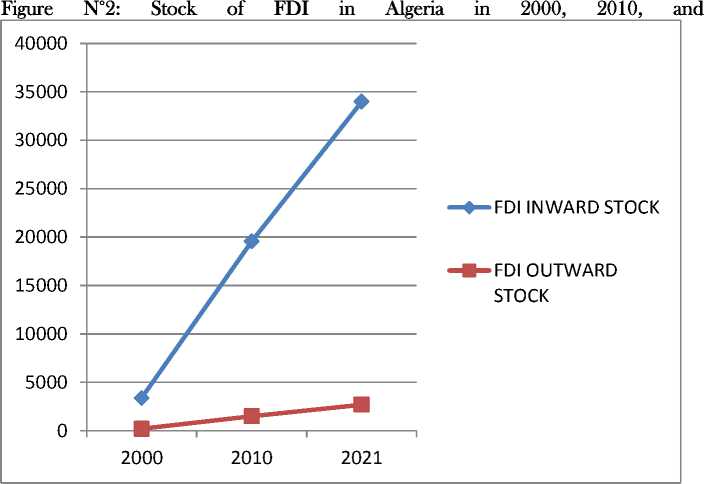

Table n° 2: FDI Stock in Algeria, in 2000, 2010, and 2021.

|

Stock d'IDE vers l'intérieur |

Outward FDI Stock |

||||

|

2000 |

2010 |

2021 |

2000 |

2010 |

2021 |

|

3 379C |

19 545 |

33977 |

205C |

1505 |

2 699 |

Source: CNUCED, FDI/MNE database (.

Source: CNUCED, FDI/ MNE database (.

The near absence of Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in Algeria during the 1980s was due to the re-evaluation of the Hydrocarbon Valorization Plan (VALHYD), which had envisioned an ambitious investment program. At that time, the government was hesitant to allow any foreign involvement.

Gradually, however, opening up to foreign investments in Algeria emerged as the preferred solution for a range of economic issues the country faced. This approach became a recurring theme, even though actual FDI figures didn't significantly increase.

-

II.1.2. Evolution of Foreign Direct Investments After Structural Reforms

A free trade agreement with the EU in 2001, and Algeria's future accession to the WTO, are likely to contribute to creating a more favorable climate for FDI (Foreign Direct Investments). To reduce its dependence on hydrocarbons and diversify exports, Algeria has, since 2000, undertaken ambitious recovery programs. Although the implementation of the association agreement with the EU opens positive prospects for FDI flows, investments from developing countries, known as "South-South" investments, are rapidly increasing. Egypt made a notable entry in 2001, positioning itself directly as the second-largest investor in the country thanks to the entry of the cellular phone operator Orascom.

Algeria has consistently attracted FDI flows since 2000. Since then, the annual FDI amount has remained above $600 million. In 2001 and 2002, Algeria ranked fourth and third respectively among FDI host countries in Africa and first in the Maghreb region in 2002. This remarkable performance is mainly due to the realization of certain strategic investments (hydrocarbons, GSM license, and steel industry). In 2003, Algeria was ranked 74th globally, behind Tunisia (38th), Egypt (58th), and Morocco (61st). In 2004, Algeria secured the first place in the Maghreb by attracting $882 million, compared to $853 million in Tunisia and $639 million in Morocco.

Despite rapid growth, FDI stocks remain relatively modest in Algeria. They increased from $1561 million in 1990 to $3647 million in 2000, reaching $7428 million in 2004. Algeria remains in the last position regarding FDI stock in the Maghreb. The FDI stock recorded in Algeria represents 41.3% of Tunisia's and 35.4% of Egypt's, which has always held the top position in this area since 1990 (BOUYACOUB, 2007).

From the perspective of capital inflows, the year 2006 was particularly characterized by a strong expansion of foreign direct investments, reaching $1.79 billion, including inter-company credits, corresponding to a 66% growth. The analysis of the structure of foreign direct investments in 2006 reveals a new phenomenon: the relative share of these investments in nonhydrocarbon sectors (53.02%) exceeded that of the hydrocarbon sector (46.97%).

The state has proposed to Gulf countries to launch projects, offering them guarantees of investment returns. For 2008 and 2009, ANDI (National Agency for Investment Development) registered only twelve (12) projects from Arab countries, eight of which are among major tourism and multifunctional complex projects, and five (5) key projects in the industrial sector. ANDI noted that the implementation of large-scale projects necessarily requires a period of maturation in planning (between 5 and 6 years, especially for megaprojects). From 2000 to the end of September 2006, ANDI processed Arab investment project files totaling $6 billion. Of these declared investments, 60% have been realized, including those of the Orascom group, which invested $2.4 billion, cement factories belonging to the same Egyptian group, and Wataniya Telecom.

-

II.2. The Effects of FDI on National IndustryII.2.1. Global Context

The Algerian economy is heavily dependent on hydrocarbons, which are often the sole analytical factor for the economy. More than 60% of state revenues certainly originate from oil taxation. Since 1977, the share of hydrocarbons has averaged 97% of exports, and their share of GDP has continuously increased (33% in 1996, 41% in 2001, 52% in 2006). These figures, of course, vary from year to year depending on international oil prices. Furthermore, A. AISSAOUI, 2001 (AISSAOUI, 2001, p. 312) estimates that a $1 change in international oil prices leads to a $700 million variation in exports and a $500 million, or even 3% of the state budget, variation in budget revenues.

The growth of total factor productivity (TFP) slowed at the end of the 1970s and became negative during the 1980s until the mid-1990s. Following structural reforms since 1994, TFP has somewhat improved. Negative factor productivity is explained by the shortcomings of the administratively managed economic system, which faced no efficiency constraints. TFP performance was hampered by relative price distortions, limited openness to non-hydrocarbon trade, and a restricted flow of FDI. The recent improvement in productivity is primarily due to the private sector's role in industry and services since 1994.

The impact of FDI on diversification cannot be qualitatively assessed due to the significant weight of hydrocarbons in the economy and because many joint ventures are still very recent. However, it can already be stated that this impact, though minimal, exists and tends to intensify. Foreign investors primarily target the national market and also aim to export to regional MENA and African markets (e.g., Henkel and Michelin) (UNCTAD, Investment Policy Review, 2004).

Reforms undertaken in the postal and telecommunications sector since 2000 have led to a richer and more varied offering of telecommunications services, significant investments (over $5 billion as of December 31, 2007), and the creation of over 16,000 direct jobs and 100,000 indirect jobs. The annual growth rate in the telephony sector is [Missing information in original text, likely a subheading break here].

-

II.2.2. Evolution of Non-Hydrocarbon Activity in 20XX [Assuming 2022 as per text]

Household consumption significantly slowed in Q1-2022 (+1.5% year-on-year), reflecting, in particular, the effect of rising consumer prices on household purchasing power.

Investment growth also remained moderate in Q1-2022 (+1.1% year-on-year), suggesting a limited recovery of public investment at the beginning of 2022; investment thus remained below pre-pandemic levels.

Furthermore, Algeria's non-hydrocarbon GDP continued a gradual recovery, reaching a level 2.9% higher than in Q1-2021. Moreover, night-lighting data suggests a continuous and transversal recovery of non-hydrocarbon activity in the second quarter (see Box 1), which available labor market data also seems to suggest (see below). (Figure 1).

-

II.2.3. The Services Sector as a Lever for Non-Hydrocarbon Growth

Still according to the World Bank report, the continued recovery of the services sector was the main driver of non-hydrocarbon activity in Q1-2022. Agricultural value added recovered year-on-year in Q1-2022 (+1.9%) after a 2021 marked by a poor cereal harvest in a context of low rainfall. 1 Furthermore, the dynamism observed in 2021 in the industrial sector moderated in Q1-2022, consistent with the absence of a strong investment recovery.

The recovery of the iron, steel, metal, mechanical, electrical, and electronic industries (ISMMEE), whose activity is mainly carried out by public enterprises, remains particularly limited (–6% in Q1-2022 year-on-year). (Figure 2).

-

II.3. Regional FDI Trends

Moderate Growth of FDI Inflows in Most African Countries

FDI flows to Africa reached a record level of $83 billion, or 5.2% of global FDI, compared to $39 billion in 2020. However, most recipients observed only a slight increase in FDI after the pandemic-induced drop in 2020. The amount of FDI to Africa was inflated by a significant intra-company financial operation carried out in South Africa during the second half of 2021. Excluding this transaction, the observed increase in Africa remains significant but is more in line with that of other developing regions. FDI inflows increased in Southern, East, and West Africa, stagnated in Central Africa, and declined in North Africa.

Table 3: FDI Inflows by African Sub-region, 2020-2021.

|

Sub-region |

2020 ( 109$) |

2021 ( 109$) |

Development ( %) |

|

All of Africa |

39 |

83 |

+ 113 |

|

North Africa |

10 |

9 |

- 10 |

|

West Africa |

9 |

14 |

+ 56 |

|

Central Africa |

10 |

9 |

- 10 |

|

East Africa |

6 |

8 |

+ 34 |

|

Southern Africa |

4 |

42 |

+ 950 |

Source : Prepared by the Researcher, drawing upon the UNCTAD report, database on FDI and multinational enterprises .

-

II.4. Evolution of FDI in the MENA Region

The mining and fuels sector has attracted the most Greenfield investments in recent years, but investment in the manufacturing sector is progressing.

FDI directed towards the MENA region has long been concentrated in a small number of sectors. The real estate and construction sector attracted the most greenfield investments in the examined economies, receiving over one-third of the total greenfield FDI announced between 2003 and 2019.

The share of investment allocated to the mining and fuels sector significantly increased during the 2013-2019 period compared to the period preceding the last economic crisis (2003-2008), while investment in real estate and construction saw its share halved. The fact that the minerals and fuels sector received a larger percentage of greenfield investments in the region than other sectors confirms the findings of studies showing that FDI in natural resources is almost unaffected by political instability (BURGER, LANCHOVICHINA and RIJKERS, 2013).

-

II.5. FDI Prospects in Light of Investment Law No. 22-18II.5.1. Analysis of the New Investment Law 22-18

Following the AIC Algeria Investment Conference, statistically, approximately 67% success and 23% waste are observed. The latter stem from banks not always "hobbling along," the difficulty of frequently accessing land within deadlines, and in some cases, defective financing or technology not being absorbed. Another significant aspect: do foreign suppliers commonly inflate their invoices? And here, centers have been established worldwide to conduct studies, for instance, if an economic operator requests a pro-forma invoice from China, France, Spain, or Germany, there is a claim to these countries to detect if there are any exaggerations. Consequently, custom and practice have amply demonstrated that the Algerian citizen wishes to operate when there is remarkable freedom of action, and when they have received money from banks, also when they are certainly supported and have the guarantee of the tax administration, and particularly when facilities have been agreed upon for them to engage in a certain project. In light of the new legal text, directions have changed; it seems that the aggregation of positive components for investment are now merged, as is the land system which is being restored, and the complete liberalization of shares. The tangible transactions being recorded are a very significant influx of foreign manifestations; there are considerably more foreigners arriving, who are clarifying and informing themselves. Consequently, at least one strategy is being discussed: "it's the spring of investment in Algeria."

As evidence, not only is Algeria a vast country, a proven subcontinent, accommodating colossal potentials of raw materials, with an abundant, admirable, and fully trained youth, on the way to learning various technical and technological sectors, which encourages foreign investors to give additional consideration. Indeed, here we highlight all these project construction processes, formulated in electrical energy, gas, water, with raw materials being very cheap proportionally to a comparative arrangement across the world. Another observation is that a list of thousands of project ideas has recently emerged, while there was concern that some investors who undoubtedly wanted to commit and did not succeed in realizing them; for this reason, a list of projects is unveiled to them for evaluation, and subsequently, by agreement, a certain number of projects are distinguished to make a final choice. However, since the promulgation of the new legal text, it is appreciated that the same concordance no longer exists, and Algeria is now fully extending its hand to foreigners; it just requires good dialogue and awareness to attract investors. There is also an imperative requirement: mastering languages: English, Spanish, Chinese.

How can the energy sector contribute to this?

-

II.5.2. Start-ups

Regarding startups specifically, many have expressed a desire to work in the circular economy, for example. There is also an imperative need to implement structuring operations. Truth be told, we cannot exclusively let these large companies and giants work alone in a relatively closed environment via multinationals, especially when we have a population fully determined to undertake, particularly young people. Consequently, the potential of SMEs/SMIs and the agricultural sector must not be underestimated. We are on a trajectory to make immense efforts towards the Great South; it's fabulous to see how these people exert efforts and invest in regions such as El Bayadh, Naama, and Ghardaïa.

-

II.5.3. ASLICAF and Industrial Land

The Minister of Industry, Ahmed Zeghdar, indicated that public authorities are currently working on the directives of the President of the Republic, Mr. Abdelmadjid Tebboune, to adapt the system governing investment. This involves the upcoming creation of national public bodies responsible for designated land.

Amir Lebdaoui, PhD in Development Economics at the University of Cambridge and Senior Lecturer at SOAS University of London, believes that Algeria's strong point remains its energy potential. He questions how this already structured sector, which benefits from a genuine industrial fabric, can serve non-hydrocarbon sectors in terms of investment.

-

II.6. Recent Changes and Horizons

According to ALGÉRIE MPO SM22, driven by the oil and gas sector, the economy grew by 3.9% year-on-year during the first nine months of 2021, after contracting by 5.5% in 2020. The recovery in hydrocarbon production was boosted by surging European gas demand and the easing of OPEC production quotas. Agricultural production stagnated due to low rainfall, and activity slowed in the services sector, but growth was driven by industry and construction. In September 2021, non-hydrocarbon GDP was still 3% below its pre-pandemic level.

Conclusion:

This Law was introduced to liberalize Algerian structures, whether public or private. Deep down, there's a wealth of existing texts: decrees, laws, and numerous field expertises, many of which have resulted in failure. However, failure is a school. This law emerges to capitalize on lessons learned, and we believe this is its core: to free state structures.

Regarding state structures, specifically the Executive within the Algerian government concerning this Law, it has been appropriately implemented through the National Investment Council. This aligns with the overall strategy. However, there's another crucial point: while we develop many strategies, on the operational front, we often find ourselves in a state of expectation. Vigilance regarding coherence is essential to initiate a strategy consisting of a set of objectives that can become imbalanced midway. This is where the National Council, under the authority of the Prime Minister, plays a vital role.