The Impact of Optimal Integration of the Holy Qur‘an in Teaching Arabic Grammar: A Case Study of First-Year Secondary School (Common Core – Etiquette Track)

Автор: Aicha R., Meriem B.

Журнал: Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems @imcra

Статья в выпуске: 5 vol.8, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper investigates the pedagogical potential of the Holy Qur‘an as a foundational tool in teaching Arabic grammar at the secondary school level. While traditional curricula often prioritize structural exercises and overlook the richness of Qur‘anic language, this study argues for the integration of Qur‘anic texts as authentic linguistic ref-erences that embody the core rules and expressive nuances of Arabic. Through a critical analysis of current teach-ing practices, the paper highlights the limited and superficial use of Qur‘anic examples in grammar instruction, suggesting that this neglect undermines both grammatical acquisition and student engagement. The proposed ap-proach advocates for a systematic and meaningful incorporation of Qur‘anic passages to enhance learners‘ under-standing of grammatical concepts while fostering a deeper connection to their linguistic and cultural identity. The Qur‘an, with its exemplary syntax and rhetorical depth, serves not only as a grammatical model but also as a bridge linking cognitive learning with civilizational awareness. Ultimately, the paper calls for a reformation of Arabic grammar pedagogy—one that elevates the Qur‘an from a peripheral to a central role in fostering linguistic compe-tence and cultural rootedness among students.

Grammar, grammatical critique, Qur‘anic references, education

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/16010676

IDR: 16010676 | DOI: 10.56334/sei/8.5.27

Текст научной статьи The Impact of Optimal Integration of the Holy Qur‘an in Teaching Arabic Grammar: A Case Study of First-Year Secondary School (Common Core – Etiquette Track)

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Impact of Optimal Integration of the Holy Qur’an in Teaching Arabic Grammar: A Case Study of First-Year Secondary School (Common Core – Etiquette Track) 4 Aicha Regagba University of Ziane Achour, Djelfa Algeria \ \ \ Meriem Benlahrech University of Ziane Achour, Djelfa Algeria Doi Serial Keywords Grammar, grammatical critique, Qur’anic references, education. Abstract

Aicha R., Meriem B. (2025). The Impact of Optimal Integration of the Holy Qur’an in Teaching Arabic Grammar: A Case Study of First-Year Secondary School (Common Core – Etiquette Track). Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems, 8(5), 254-263; doi:10.56352/sei/8.5.27.

Praise be to God, Lord of the worlds. To Him belongs all praise in the first and in the hereafter, and to

Him belongs judgment and to Him you will be returned. I bear witness that there is no god but God alone with no partner, and I bear witness that Mu- hammad is His servant and Messenger. As for what follows:

We seek to preserve the Arabic language with the Qur’anic text; We must not forget that the Holy Qur’an is the greatest book of Arabic, the carri-er(bearer) of its rules, the container of its methods and structures, and all the forms of its construction as an artistic tool that expresses life and civilization. The Qur’an, then, is worthy of its methods and structures being the model from which the learner begins on the journey of acquiring the language as a linguistic faculty and as scientific knowledge that he transmits to other learners.

We have noticed that the grammatical and linguistic contents in academic curricula do not give the Qur’anic witness its place. It is used in citation and representation only a little, so we must draw attention to the importance of teaching grammar and all levels of the linguistic system of Arabic in the Holy Qur’an. It is the rules, it is the methods, and it is the faculty that the learner acquires automatically with frequent practice and repetition of models.

The basic question around which our discussion of the topic of teaching grammar in the Holy Qur’an revolves is: What are the practical implications of employing the Holy Qur’an in teaching grammar in secondary education?

-

1- Research methodology

To study this problem and its ramifications, we will adopt the descriptive approach with analysis in describing the relationship of teaching grammar to the Qur’anic text, and demonstrating the impact of employing the Holy Qur’an in teaching Arabic grammar. We will also adopt the deductive approach to accompany the description and analysis in the applied study attached to this research.

Previous studies related to the research: There are many studies that dealt with teaching the Arabic language in general, and Arabic grammar in particular. Its issues were addressed across the various stages of education, and these studies varied between theory and application, and they are almost unlimited, and I have used a number of them in this article. These include: the work of the symposium on facilitating grammar held in April 2001 at the National Library in Hamma, scientific grammar and educational grammar and the necessity of distinguishing between them by Professor Dr. Abdel Rahman Haj Saleh, the morphological miracle in the Holy Qur’an by Abdel Hamid Hindawi, and “The Virtue of the Holy Qur’an in Preserving and Enriching the Arabic Language” by Khair Al-Din Khoja, and “Technical Employment of the Holy Qur’an in Teaching Arabic to Speakers of Other Languages” by Muhammad Abdel Fattah Al-Khatib, Muhammad Abdel-Latif Rajab Abdel-Ati, and others;

Commenting on previous studies related to the research: This study aims to illuminate the aspect of benefiting from the Qur’anic text in teaching gram- matical rules in the general education stage, and to focus on the method and conditions that make this approach the beginning of success in teaching grammar.

The first section (theoretical framework of the study): Teaching grammar and the Holy Qur’an:

-

2- Teaching grammar and its goals:

-

2 .1-What is the grammar that needs to be taught?

The justification for asking this question is the distinction between two types of grammar - as is known -: scientific (theoretical) grammar, and didactic (educational) grammar, and the difference between them, as Youssef Al-Saidawi says:« It is the difference between the rules and grammar; The rules are monitoring what the Arabs said, clarifying it, and formulating its rulings. As for grammar, it is the implementation of the mind in all of this, and the rules remain the same, but the mental journey in them may be long or short » (Yusuf, 1999, p. 17); Scientific grammar is taught for itself; It is specific and seeks accuracy, depth, and abstraction (Bouteraa, 2011/2012, p. 56) It is a pure science , which includes the scientific study of everything that surrounds man, and man himself, including language as a phenomenon and system of evidence, and only stubborn people deny this.

Educational grammar is taught to improve the language and writing and choose the appropriate material that the learner needs. It is a useful, functional grammar that is based on linguistic, psychological, and educational foundations at the same time, and is not merely a summary of scientific grammar, We do not expect to find the educational purpose and language acquisition behind scientific grammar as well; One of the first reasons for the emergence of Arabic grammar was the acquisition of the language by non-Arabs.(Abd al-Rahman, p. 145)

It is mentioned here that voices have risen in the modern era complaining about the low level of learners, and the dryness of the grammar provided to them, It is not difficult for those who work in teaching grammar to notice the large number of grammatical errors and the inability to distinguish morphological structures; Rather, the weakness reached the point that students had many spelling and expression errors - and this is an old call in any case - and the objections of modern grammarians to grammar came from five directions (Tewati, 2004, p. 44):

-

■ In terms of its style and presentation to stu

dents;

-

■ In terms of his approach and the exaggera

tion in mixing it with philosophy;

-

■ In terms of its definition, that is, the subject

of grammar itself;

-

■ Factor theory;

-

■ Secondary and third reasons, or what are

called grammatical reasons.

Here we return to the issue of the distinction between scientific grammar and educational grammar. To realize which grammar should be simplified, and which grammar should be presented to the student. Facilitation only affects the form in which the rules are presented to the learner. That is, simplification in how to teach grammar, not in grammar itself. Abd al-Rahman Haj Saleh denied the claim of simplifying grammar. He said: « How can grammar be simplified when it is the law on which the tongue is built! .

The grammar that the student must be aware of is the educational grammar with a simplified image and clear rules, which is subject to the scientific selection of the grammatical material taking into account its nature, based on the renewed and diverse data in linguistics, psychology, sociology, and pedagogy, and taking into account the students’ progression in the learning process. In the early stages of his studies, the student is satisfied with grammar at the educational level that suits his abilities. If he goes to university and specializes in Arabic, he must go beyond that to understand scientific grammar, and this will be according to a well-studied curriculum. Because educational data requires that education and learning be subject to the engineering of the curriculum, the specifications of the permanent assessment system, and the interaction between the curriculum, education and assessment in all its dimensions, according to a linguistic policy determined by the strategy adopted by educational planning.

2-1 What is the purpose of teaching grammar?

The approach to teaching grammar is determined by reference to the goal of studying it. The early grammarians stated that learning it aims to acquire fluency, so that those who are not native to Arabic can catch up with native Arabic in eloquence - as Ibn Jinni put it - and therefore there is no crime that the modern researchers in language education have determined the rules for teaching grammar; Objectives represent the foundations for planning the educational process and teaching strategies. The starting point was to separate the scientific aspect from its educational aspect, and then« there is no escape from an objective view of teaching Arabic grammar, as it must be functional that the learner needs in his educational or professional life, as he does not need all the information contained in grammar books to the extent that he needs It has what leads to proper control of the language in the field of learning » (Hedges, 2019); Therefore, a number of objectives of teaching Arabic grammar for the secondary stage and beyond can be identified as follows:

-

■ Forming correct linguistic habits among students and training them to use words, sentences and phrases correctly.

-

■ Increasing students’ vocabulary thanks to the examples, evidence, and correct structures they study.

-

■ Addressing errors that are common in students’ linguistic use.

-

■ Teaching comprehensive rules that control the use of various expressions in similar linguistic usage situations.

■

Reaching the level of understanding the language that is passed down through generations, and knowing the foundations that govern it, which facilitates understanding meanings easily and expressing them clearly and smoothly.

-

■ Developing students’ ability to criticize and distinguish between right and wrong what they hear or read; Because the study of grammar involves analyzing words and styles, knowing the relationships between them and their meanings, knowing poor or good styles, and understanding the functions of words and styles.

-

■ Training the mind in organized thinking, correct conclusions, accurate linking, and sound balancing; The study of grammar is not devoid of these skills.

Moreover, the intended goals cannot be achieved without taking into account the following aspects:

-

■ The nature of the learners in terms of their real abilities, their linguistic, cognitive, intellectual, social and psychological levels, and their relationship to their surroundings.

-

■ The nature of the academic material that is used based on the concept of language.

-

■ Pedagogical practice, which is based on everything that ensures effective communication between teachers, learners, and the academic subject.

-

2 .3 Grammatical Criticism

It is well established that Arabic grammar is one of the most deeply rooted sciences that developed within the Arabic language, originally in service of the Holy Qur’an and as a means to preserve the integrity of Arab speech following their contact with nonArabs. This discipline received great attention from scholars since the early ages, leading to the emergence of grammatical schools and a diversity of authorship methodologies.

Nevertheless, this science has not been immune to criticism. Scholarly voices, both historical and modern, have criticized its complex terminology, its occasional rigidity in adapting to linguistic development, and its detachment from practical application in teaching the language to younger generations.

Contemporary criticism of grammar focuses on calls to simplify its rules and to connect them with real-life linguistic contexts, rather than relying solely on theoretical memorization. Criticism has also been directed at school curricula, which often present grammar as an isolated subject, thereby depriving learners of the motivation and ability to apply it in expression and comprehension.

In this context, there arises a pressing need for a modern critical reading of the reality of grammar instruction—one that examines its effectiveness, relevance, and methods, and seeks to develop it in a way that meets the goals of contemporary language education. This is especially true when grammar is taught through a rich context like the Qur’an, which repre- sents the highest and most impactful linguistic model for Arab learners.

It is noteworthy that the term "grammatical criticism" is a compound expression made up of two words: criticism and grammatical. It is a descriptive compound, where the first word typically remains constant, while the second word varies. Thus, we find “criticism” recurring in many compound terms such as: grammatical criticism, linguistic criticism, literary criticism, rhetorical criticism, stylistic criticism, scientific criticism, historical criticism, social criticism, and so on.

When examining the word grammatical, it denotes that the subject is related to grammar. However, the term grammatical criticism differs from the aforementioned terms in that it refers specifically to criticism from a grammatical perspective. That is, it is a form of critique that evaluates its subject strictly through the lens of grammar. This type of criticism involves the critic expressing views and evaluative judgments regarding particular grammatical issues—usually issues that are the subject of scholarly disagreement among grammarians. However, these judgments are not issued arbitrarily; rather, they are based on the fixed grammatical rules that guide the grammatical critic’s evaluation

-

3- The importance of Qur’anic sciences in the grammar education industry: How do we benefit from Qur’anic sciences?

The sciences of the Qur’an have two meanings: an additional meaning and the meaning of knowledge of the written art. The first means the types of sciences and knowledge related to the Holy Qur’an, whether they serve the Qur’an with its issues, rulings, or vocabulary, or the Qur’an indicates its issues or guides to its rulings. The second is investigations related to the Holy Qur’an in terms of its revelation, collection, readings, interpretation, abrogated and abrogated, and the reasons for its revelation, Mecca, Medina, and so on. What is meant by the sciences of the Qur’an here is the first meaning, and they are the sciences that serve the Holy Qur’an in itself, in an effective exchange process between the language and the Holy Qur’an. The Arabic language is the vessel of miracles, as it is the one that carried the verses of the Holy Qur’an and was chosen by God Almighty to be the language of Islam. Qur’anic expression carries within it the secrets of the Arabic language that cannot be replaced by another expression, or an expression in another language, as well as structures and sentences, for there is no other language. It can contain this huge mass of connotations, vocabulary, connotations, images, structures, collocations, alliteration, syno-nyms...etc., like the Arabic language; The Arabic language enabled the Qur’an and the Qur’an enabled the Arabic language (Manaa, 1988). Indeed, the Holy Qur’an has clear effects on the Arabic language, including: preserving the language from loss, strengthening the language and advancing it towards perfec- tion, unifying the Arabic dialects, transforming the Arabic language into a global language, and creating language sciences such as grammar, morphology, and rhetoric, and all of this refers to The importance of the Holy Qur’an in teaching the language and creating its sciences, at both the scientific and educational levels.

We begin by emphasizing the importance of the Holy Qur’an in teaching the Arabic language, based on the fact that the Holy Qur’an is the source from which the sciences of the Arabic language, including Arabic grammar, arose, and that this grammar can only be understood and assimilated in the most complete manner if one starts from the Qur’anic text. No Arabic text, whether poetry or prose, whether its rhetorical status is high or not, rises to the level of perfection in teaching the grammar of the Arabic language, as would be the case if reliance was placed on the Holy Qur’an, especially when the teacher is an expert in the Holy Qur’an at all levels, and the educational content is It agrees with the learner, and is appropriate for him, while relying on the sciences of the Qur’an to support clarification and explanations, such as the science of interpretation, readings, provisions of Tajweed, and so on.

But how can we benefit from the sciences of the Holy Qur’an in teaching grammar?

The answer to this question comes as follows:

■ The Holy Qur’an is the key to synthetic grammatical study, and its sciences serve it and the grammar of the language.

■ The Qur’anic text possesses all the characteristics of the ideal, high Arabic language in structure, eloquence, style, and connotation... (the complete language)

■ We can notice in the Qur’anic text two important aspects of the educational process:

■ The first aspect: is that the Qur’anic text is a text that carries both the linguistic level and the aesthetic artistic level, which are the basis of what the learner needs in learning the language.

■ The second aspect is that the Holy Qur’an is a text for use. It is alive in the daily use of learners, through worship and recitation, and the fact that it is a text for use means that it is not as far from the learner as poetry is from him, for example, as it is words that he circulates in his life. Therefore, it is more useful in the educational process. It is more useful than examples taken from general and artificial linguistic life, such as: Zaid struck Omar.

■ The sciences of the Qur’an (especially the science of interpretation) include what is useful in clarifying the text and clarifying linguistic rules, and the positions of their use in a way that cannot be matched by an educational curriculum or academic content. This is what led us to believe in the possibility of creating a synthesis of teaching grammar in the Holy Qur’an, provided that Literary texts of poetry and prose are included in the study of other levels of language.

The second section (applied framework): An applied study of employing the Holy Qur’an in teaching grammar (First year secondary school lessons, Arts and Philosophy Division)

-

3.1 Description of the study sample and its tools: lessons for the first year of secondary education, a com-

mon core of literature, and these lessons are distributed between grammar and morphology as shown in the table :

Grammar rules:

Morphology rules:

Asserting the present tense verb using tools that assert two verbs

The crier

Original and ordinal number

The present tense verb is nominative and accusative

Absolute effect

The verb and its temporal significance

The subject, the predicate, and their types

Adverb

The abstract verb and more and the meanings of the letters of the increase

was and her sisters

Effect for it

Actor name and exaggeration forms

The characters are already suspicious

Discrimination

Object name

Cad and her sisters

Adjective of both kinds

Prohibited from exchange

No denying sex

Emphasis

Name of place, time and instrument

Object

Allowance

Suspicious adjective

This is the content of the course since the 2005/2006 season, and it is distributed over twelve educational units, from which the last two units have been omitted, due to the length of the program and the inability to complete it, most teachers do not exceed the seventh unit, and rarely one of them reached the tenth unit. It is noticeable on this content that it varies between grammar and morphology, and grammar lessons combine what is related to the nominal sentence and the actual sentence; As for the lessons of morphology, they vary between the study of verb forms, derivatives and numbers, and the topics have been omitted: "the name of the object, the forbidden from morphology, the name of the place, time, the machine and the similar adjective."

Study tools: The tools of applied study are represented in the textbook for the first year of secondary arts, philosophy and philosophy, as it is the code from which we take the most important information about the content of the course, in addition to the total notes of lessons completed by the professor, And books and articles, some of which relate to the study of Arabic grammar according to Quranic grammar, and some of them are studies in the Holy Quran, and we will prove them in the list of research references.

Analytical study:

escription of the reality of teaching grammar and morphology for the first year of secondary school:

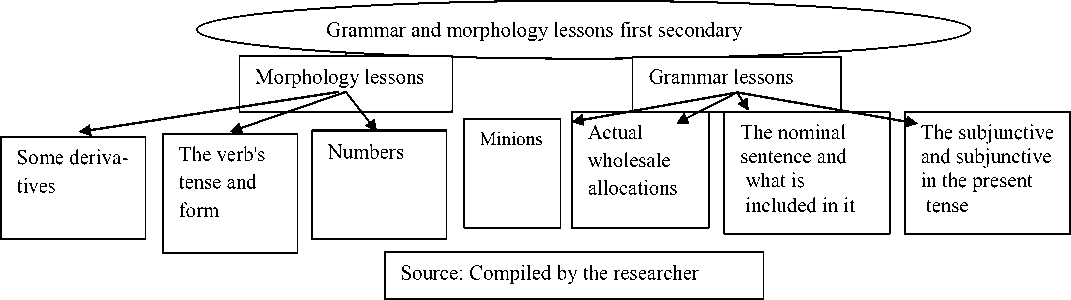

The course includes twenty lessons, where the last four lessons (the noun of the object, the forbidden to morphine, the name of the place, time and machine, and the similar adjective), which vary between grammar and morphology, but grammar topics are predominant. Grammar lessons can be divided into four axes: the present tense verb and its nouns, the nominal sentence and what enters it, the allocations of the actual sentence, and the dependencies, and dividing them into axes means that there are relationships between the lessons that belong to one axis and serve each other, and the teacher should exploit this point as much as he can to that way. Morphology lessons are divided into three axes: numbers, verbs in terms of time and formula, and formulas of some derivatives. This can be illustrated by a diagram:

Figure 1: A diagram showing the axes of grammar and morphology lessons for the first year of secondary school, Arts and Philosophy Division

As for strategies for teaching grammar and morphology, the method used according to the textbook and the professor’s notes is the inductive-deductive method, which is a method based on starting with examples, which are explained and discussed, and then the rule is deduced from them. The lesson begins with an introduction, followed by displaying examples on the blackboard and reading them by the students and the teacher, then comes the discussion and observation of the morphological or syntactic phenomenon studied ; This is done by linking and balancing the sentences in terms of common characteristics and different characteristics. The budget includes the type of words, their relationships, their function, their position in relation to others, and their grammatical mark. The rule is then devised with the participation of the students, and written on the blackboard in easy language. All of this is followed by applications and multiplication of examples to consolidate the rule and practice it.

Evidence and examples: taken from the literary or communicative text on which the rest of the learning is built; Grammar lessons are among the objectives required to be learned accordingly. We may find evidence from outside the text, but the Qur’anic witness has little luck here. By following the Quranic evidence at the level of the entire book, we found that the total number of examples does not exceed twenty-four examples, and that six of the lessons are devoid of Quranic evidence, and eight lessons are not detailed in the book, which is the teacher’s achievement according to the method used in the rest of the lessons. The Qur’anic examples mentioned in the book range from their presence in presenting the lesson, in building the grammatical base, and in applications and exercises. Here we notice that the Qur’anic witness is not benefited from despite its importance, and it is not taken within its context, even though the context is one of the most important clues to understanding the sentence and determining the functions of its elements.

In this regard, we see that it is inappropriate to present grammar and morphology according to a strategy that does not make the Holy Qur’an a key to it, which is the first codifier of the Arabic language and the bearer of its meanings and structures. The saying of one of the researchers in the applied example applies to it, as he says: «The example that should be It is approved that it must achieve a number of goals in the life of the individual and society, and achieve a good understanding of the rule, far from any complexity, through the context in which the intended example appears. The example must also achieve value in the learner’s soul, contributing in some way to his evaluation and reform. And to build him as an individual fit for life, and to achieve in the student the development of the artistic taste that the Arabic language possesses» (Abdelmajid, 2008,) , and there is no example in Arabic that achieves this like the Holy Qur’an. Therefore, we present here a different vision for presenting the grammar lesson to secondary school students. This vision is based on the centrality of Quranic grammar, and makes it the basic strategy in teaching grammar. In order to prove the merit of this approach, we will resort to a process of comparison between the achievements in the textbook and the teacher’s notes and the proposal we present in this context.

3-2 Activating the role of Qur’anic evidence in teaching grammar and morphology and its impact on achievement :

The purpose of choosing examples for the lesson is to consolidate the rules for the student, and the purpose of consolidating the rules is to use them well in linguistic communication, and the Qur’anic example is more appropriate for this than any other; In that it gives the witness a context that reminds the learner of the communicative context, and alerts him to the need to take into account the circumstances of the speech and the context of the sentence to know the grammatical meanings, and not just stop at justifying the inflectional movements at the end of the words.

In this regard, we have chosen examples of lessons to highlight the role of the Qur’anic witness in consolidating and controlling the rules for the learner. These selected lessons are: the subject and the predicate, the verb and its temporal significance, Let's start with the subject and the predicate:

Lesson of the subject and the predicate :

Among the Qur’anic examples mentioned are: God Almighty’s saying: wa-an ta s bir u khayrun lakum (“And that you may be patient is better for you”) [An-Nis a’ : 25], and His saying: wa-min a y a tihi annaka tar a al-ar d a kh a shi ‘ ah (“And among His signs is that you see the earth humbled”) [Fussilat: 39], to represent the coming of the subject as an interpreted source; and God Almighty’s saying: wa-al-s a biq u n al-s a biq u n O l a' ika al-muqarrab u n (“And the forerunners, the forerunners – those are the ones brought near [to Allah]”) [Al-W a qi ‘ ah: 10-12], to represent the link between the predicate, the sentence, and the subject.

To represent the nominal sentence in general, the book cited an example from the text studied before, which is the poet’s saying:

The doctor tells you: I have your medicine .

* If he feels your palm and arm I am the slave you learned about

* You have examined me, so let the listener Examples include: Knights of Antara? The brave is not defeated. The wise man has good character, travel reveals the character of men, and glory is under the banner of knowledge.

Note the following examples:

- They are various examples that include issues that are scheduled to be taught to the student, but they do not include all the rulings related to the subject and the predicate.

- Examples need to be supported by other examples in order to train and consolidate the rules.

- These examples revolve around defining the essence of the subject and the essence of the predicate, and the relationship between them.

What seems to me here is that the example of “: I have your medicine” used to define the nominal sentence and specify its components does not suit the purpose for which it came; It lacks the grammatical mark, which may confuse the student in determining the grammatical function of the elements of the sentence. The same applies to the sentence “I am the slave”; However, the last example may not contain the meaning of the information, and the meaning appears as if it is a trivial matter known to every human being, as we are all slaves. One of the conditions for accepting the news is that it should not be trivial and useless. And the student, even if he does not know this grammatical rule, may be led by his linguistic intuition into confusion. A more appropriate way to clarify this is through an example from the Holy Qur’an, as in God Almighty’s saying: Allahu waliyyu alladhina amanu (“Allah is the Guardian of those who believe”) [Al-Baqarah: 257]. The context clarifies the boundaries of identifying the subject, the syntactic indicator is evident, and the nominalization of both the subject and the predicate is clear.

Then follow examples that elaborate on the nature of the subject, particularly when it comes in the form of an interpreted verbal noun (ma s dar mu ’ awwal), as in the Almighty’s saying: wa-an ta s bir u khayrun lakum (“And that you may be patient is better for you”) [An-Nis a’ : 25]. Thus, grammatical rulings proceed in harmony with the Qur’anic context. In cases where the subject appears without an explicit predicate in the nominative structure, it is preferable to provide an example that supports both the functional and contextual meaning, such as in the Almighty’s saying: a-r a ghibun anta ‘ an a lihaQ y a Ibr a h i m (“Are you averse to my gods, O Abraham?”) [Maryam: 46]. Here, the beginner (mubtada ’ ) is described in a way that renders the predicate unnecessary, which highlights the functional meaning conveyed in the sentence.

This example also illustrates the possibility of inversion (taqd i m wa-ta ’ kh i r) between the sentence elements, drawing the learner’s attention to the importance of meaning, as specifically intended in the verse. This approach moves beyond the formal aspect of grammatical rules. For instance, in the construction a-r a ghibun anta , the inversion emphasizes that the focus of the question is not on the subject (“you”) but rather on the action being questioned. When the rhetorical purpose is to inquire about the predicate, it is placed before the subject. Each element in such structures is the focus of the question and draws the attention in the sentence, as Al-Jurj a n i pointed out in Dal a 'll al-Ij a z. A similar example is the Almighty’s saying: a-anta fa ‘ alta h a dh a bi- a lihatin a y a Ibr a h i m (“Is it you who did this to our gods, O Abraham?”) [Al-Anbiy a’ : 62].

There is no harm in making such structures clear to the student; rather, this clarity demonstrates rhetorical purposes and facilitates language acquisition across all levels simultaneously. In discussing the types of predicates and the links that connect them to the subject, it is necessary to broaden the range of examples to cover all forms of syntactic linking — and the Holy Qur’an provides ample and enriching material for this purpose, including the Almighty’s saying...:

As in the Almighty’s saying: al-q a ri ‘ ah (1) m a al-q a ri ' ah (“The Striking Calamity! What is the Striking Calamity?”) [Al-Q a ri ‘ ah: 1-2], which includes repetition of the subject using the same lexical item within the predicate sentence. Similarly, in the Almighty’s saying: wa-lib a su at-taqw a dh a lika khayr dh a lika (“And the clothing of righteousness — that is best. That is...”) [Al-A ‘ r a f: 26], we find the use of a demonstrative pronoun that refers back to the subject.

Thus, we find that the Qur’anic examples provide a rich contextual fabric that facilitates the syntactic and semantic linking of sentence elements. These exam- ples transcend the artificial constructions often found in traditional grammar books, which tend to be decontextualized and disconnected from practical linguistic use.

- Study the verb and its temporal significance:

This topic is one of the fertile topics as it requires showing the link between the word and the meaning. Therefore, it is most in need of using the Qur’anic text to represent it and explain it to the student, as it is known that «the construction of “he did” and the construction of “ he does” cannot indicate time with its divisions, boundaries, and minutes. ; Hence, the Arabic verb does not reveal time in its form, but rather time is obtained from the structure of the sentence, as it may include additions that help the verb to determine time within clear limits », and the Holy Qur’an has ample room to teach the details of this topic, using two factors: the Qur’anic linguistic context and the level. Rhetorical Quranic expression; The examples we present now explain the idea and clarify the proposition:

1 - The past tense is defined as that which indicates that an event occurred prior to the time of the speaker. It is most commonly expressed in the form of “he did” , as in the Almighty’s statement:

"Wahuwa alladh i khalaqa allayla wa al-nah a ra wa al-shamsa wa al-qamara" ( It is He who created the night and the day and the sun and the moon) [Al-Anbiy a ’: 33].

The present tense , on the other hand, is defined as that which conveys a meaning in itself that is linked to a time that may refer to the present moment or the future. It is usually expressed by the form “he does” , as in:

"Yawma naq u lu li-jahannama hal imtala’ti wa taq u lu hal min maz i d" (On the Day We will say to Hell ‘Have you been filled?’ and it will say, ‘Are there any more?’ [Q a f: 30].

However, temporal reference—whether past, present, or future—is not always determined solely by the form of the verb. Rather, it is often inferred from contextual clues accompanying the verb. These clues are numerous and varied. It is also possible for the past tense to be used to indicate the future, and vice versa.

While students learn certain grammatical rules to guide them in identifying verb tenses, these rules do not always account for all contextual nuances. For instance, in the verse:

"Ata amru Allahi fa-la tasta'jiluhu" (The command of Allah has come, so do not hasten it [Al-Nahl: 1], the verb “‘tla ” (has come) appears in the past tense, yet it conveys a future meaning—namely, the imminence of the Day of Judgment. The Qur’an employs the past tense here to emphasize the certainty and nearness of the event.

Therefore, it is pedagogically more effective to provide students with exercises drawn from the Qur’an itself. Such exercises help them develop the ability to interpret the interplay between verb forms and contextual indicators, supported by simplified explanations that clarify complex vocabulary and meanings. Many Qur’anic examples reflect this stylistic feature, such as:

"Wa tarakn a ba' d ahum yawma’idhin yam u ju f i ba‘ d , wa nufikha f i al- su r fa-jama‘n a hum jam‘ a " (And on that Day We will leave them surging over each other, and the trumpet will be blown, and We will gather them all together ) [Al-Kahf: 99],and:

"Wa ashraqat al-ar d u bi-n u ri rabbih a wa wu d i'a al-kit a b" (And the earth will shine with the light of its Lord, and the record [of deeds] will be placed ) [Al-Zumar: 69].

These examples demonstrate the rich linguistic fabric of the Qur’anic style, where verb forms are used with remarkable rhetorical precision, transcending the confines of grammar books and reflecting language in dynamic, meaningful use.

The verbal context may exist, but it needs to be examined in order to clarify the moral differences. It is clear that the s i n is a tool of catharsis, and it is « specialized in the present tense, and devotes it to reception.” Such as “No, they will know » (Badr al-Din & Al-Janna al-Dani, 1992), its meaning may be confused with “suf” entering the present tense and indicating reception as well. Ibn Malik said: «...the Arabs expressed the one meaning occurring at one time with: He will do, and he will do» (Badr al-Din & Al-Janna al-Dani, 1992), so it is Where can the student explain the difference between: I will visit you and I will visit you, when it is often said in grammar that the s i n is for the near future and the suf is for the far future, and we have the rule “Every increase in the structure leads to an increase in meaning?” Perhaps the accuracy of the difference in usage appears only in the Qur’anic expression. God said: “Inna alladh i na kafar u bi- a y a tin a sawfa nu s l i him n a ran.” (An-Nisa 4:56).

And the Almighty also said:“Sayasl a n a ra al-lahab.” (Al-Masad 111:3).

Abu Hayyan mentioned that the verse from Surah An-Nisa carries a threat that comes after His state-ment:“Wa minhum man sadda ‘anhu wa kafa bija-hannama sa‘ira.” (An-Nisa 4:55). This follows and explains what is stated in it. In the verse of Surah Al-Masad, Abu Hayyan says: “The sin indicates the arrival [of the event], even if time is delayed, and it is a promise whose fulfillment is inevitable.”

Al-Tahir ibn Ashour stated that “ sawfa is a particle that enters the present tense and transforms it into the future tense, and it is more likely synonymous with s i n. Some grammarians said: sawfa indicates a more distant future, which they called procrastination, but there is nothing in its usage that supports this.” He said this when commenting on God’s words: “Fa sawfa nu s l i hin n a ran.” (An-Nisa 4:30).

He also said, interpreting the Almighty’s saying: “Wa sayasl a na sa’ i r a .” (An-Nisa 4:10),“The s i n in sayasl is a letter of approach, meaning reception; that is, it enters the present tense and prepares it for reception, whether the reception is near or far, and it is synonymous with will . It was said that it may indicate a longer period of time. In the context of a promise, it serves the purpose of fulfilling the promise and also the threat.”

Thus, you see the difference in their usage. The difference between them lies in how they are arranged and their semantic purposes. The s i n in “He will burn in fire” is only at the beginning of the statement, indicating emphasis and the nearness of fulfillment, whereas sawfa in “We will burn them” lacks this emphasis due to the absence of conjunction and initial position in the structure, thus indicating an absolute and distant reception.

Hence, the student can realize the subtle semantic differences between verbal clues indicating time in sentences, which may appear similar and cause confusion in ordinary speech. A student should not think that interpreting the Qur’anic text is beyond their level or that analyzing its texts is beyond their ability. Because adherence to clear and tangible rules linking pronunciation and meaning, as shown in these examples, suffices to consolidate understanding and master the language at a high rhetorical level. Indeed, memo-rizers of the Qur’an and students in Quranic schools are often those who best acquire the language and are most capable of speaking it fluently and creatively.

This approach applies to all grammar lessons, including syntax and morphology. Abstract and causative verbs can be studied using this method, overcoming the artificial and stereotyped approach that fixes meanings for affixes, far from linguistic context. The same applies to lessons on active participles, exaggerated forms, and so forth. The key is for the student to learn the meanings of these forms and their uses in various contexts, thereby building their own curriculum that enables them to analyze new patterns they have not encountered before. This forms a link between grammar and rhetoric by connecting structure, stylistic significance, and aesthetic systems.

Since the best methods for teaching grammar rely on a linguistic constructionist approach—repeating phrases to achieve desired goals, ensuring examples are suitable and meaningful to learners, and choosing linguistic patterns that strengthen learners’ tongues and guide them to meaningful language use—it is necessary to benefit from verbal similarities in the Holy Qur’an. The Qur’an contains repetitions of examples with similarities and differences that benefit learners by offering diverse and abundant exercises, without deviating from educational goals. This suits learners’ minds and helps improve their fluency, especially in highlighting semantic differences according to structural and systematic distinctions.

Conclusion

The optimal investment in employing the Holy Qur’an in teaching Arabic grammar is one of the important strategies that the maker of the grammar educational curriculum should follow. The learner finds flexibility and ease in understanding the rules and testing their consolidation in his mind through applications and use in various situations and contexts, when the Qur’anic text is frequently used as examples, for two reasons: The first: Because education depends on the competency approach, which makes the learner make a clear effort and work his mind in understanding, applying and using, on the one hand. Second: On the other hand, the Qur’anic text is the example and has the rule and application, and the student composed this text; He has prior knowledge of it, and its frequent involvement in the various activities of his life. He does not find difficulty in establishing, applying, and using the grammatical rule, and it is clear that this rule will continue to follow him in life as long as the Qur’anic text is with him in his worship, prayer, and reading, and in his various linguistic situations. This is a unique feature of using the Qur’anic text in teaching grammar, unlike the use of various examples from Artistic language (poetry and prose) and non-artistic language.

In addition, the Qur’anic example is unique in its ability to study language in an integrated manner. It combines the study of language levels at the same time thanks to its linguistic context and eloquent style, and it can be considered the bearer of the educational curriculum for the Arabic language.

Therefore, recommending the optimal use of the Qur’anic text in teaching Arabic grammar constitutes one of the most important recommendations of this article, which we present as follows: It is essential to thoroughly train teachers in the sciences of the Holy Qur’an, particularly in parsing, interpretation, and the reasons for revelation. A dedicated subject on Qur’anic sciences should be introduced alongside other subjects, adapted to each educational level and continuing throughout the general education stage, as it directly supports teaching Arabic language skills— phonological, morphological, syntactic, rhetorical, and semantic. Qur’anic evidence and examples should replace those drawn from everyday speech or literary texts due to their sufficiency and comprehensiveness. Teachers should parse entire Qur’anic vers- es related to the studied phenomena, recalling any previously covered content, to foster an integrative approach that combines reading, writing, speaking, and listening within the context of the Qur’anic text. The Holy Qur’an encompasses all eloquent linguistic levels: it teaches Tajweed and proper pronunciation, morphology aligned with intended meanings, syntax with its varied readings, comprehensive parsing, semantics, and enriches rhetorical artistry. Finally, it is vital to distinguish between contemporary Arabic— which tends to be diluted and mixed with dialects— and the pure, sophisticated Arabic of the Qur’an, promoting the latter as the model language for learners to ensure linguistic precision and depth.