The Influence of the Russian Orthodox Church on the Development of Schools and Education in the North Caucasus

Автор: Psikhomakhova Aminat Rashidovna

Журнал: Bulletin Social-Economic and Humanitarian Research @bulletensocial

Статья в выпуске: 18 (20), 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Orthodox missionary work in the North Caucasus has had a thorny path in its development. Different factors had a huge impact on the specifics of activities: the policy of the state and the position of the Church. Missionaries played a great role not only in the propaganda of the Orthodox faith, but also in strengthening the state authority in the national outskirts. They rendered great assistance in the dissemination of enlightenment and social support for the population.

Orthodox missionary work, North Caucasus, politics, state, enlightenment

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/14127632

IDR: 14127632 | DOI: 10.52270/26585561_2023_18_20_66

Текст научной статьи The Influence of the Russian Orthodox Church on the Development of Schools and Education in the North Caucasus

Today, society is undergoing reconstruction of the social system. The destruction of social foundations is accompanied by crisis phenomena, contributes to the creation of new ideas for spiritual renewal, the search in the past for answers to the questions of our time. Russia today shows a profound transformation of public consciousness. The question of the role of the Orthodox Church in the enlightenment of the peoples of Russia is becoming topical.

Without the role of religion it is difficult to imagine the history of Russia. Issues of faith are of great importance for modernity. The degree of respect and benevolent attitude towards representatives of different confessions, between believers and non-believers, demonstrates the level of civilization of society. In modern Russian society it is very important to adhere to confessional tolerance, as it is very important for the security and integrity of the country.

The study of the experience of missionary activity allows one to expand the understanding of the processes associated with the entry of the peoples of the region into the Russian Empire.

-

II. METHODOLOGY

The methodological foundations of the study are based on the principles of historicism, objectivity and comprehensiveness, the application of which made it possible to recreate a holistic picture of the activities of the Russian Orthodox Church in the region under study in the pre-revolutionary period.

-

III. DISCUSSION AND RESULTS

The studies devoted to the missionary activity of the Russian Orthodox Church are one of the insufficiently studied pages of history. Of particular interest are works from the pre-revolutionary period. The work of Archpriest Ioann Belyaev, Bishop of Vladikavkaz, and Baron Pyotr Karlovich Uslar, a military engineer, linguist and ethnographer, note the positive role of the spread of Christianity in the Caucasus. A number of works by Butkov P.G., Prozritelev G. N., and N.F. Dubrovin, narrate fragmentarily about the activities of the Russian Orthodox Church in the context of the policy carried out in the Caucasus. The influence of Christianity is noted in the works of the clergymen themselves. The activities of the parochial schools are noted in the works of M.V. Krasnov and L.N. Modzalevsky. The Charter and the report of the Society for the Restoration of Orthodox Christianity in the Caucasus are of great value.

The Soviet period is marked by works on Ossetian writers, and by A.R.Shikhsaidov's publication on the penetration of Christianity in the Caucasus.

The modern period is marked by a number of works. Of particular note is the work of Gedeon, Metropolitan of Stavropol and Baku, who examines the history of the Caucasian and Vladikavkaz diocese on the basis of various sources. P.G. Nemashkalov's works consider the formation and functioning of the eparchial system of the Russian Orthodox Church in the North Caucasus from the end of the 18th century to the 1860s. The works written in the pre-revolutionary period are republished.

The North Caucasus is one of the oldest cradles of Christianity in Russia. The North Caucasus was characterised by a mixture of pagan, Christian and Muslim beliefs. The inaccessibility of many parts of the North Caucasus helped to preserve the remnants of old beliefs and gradually mingle them.

Various missionary societies were established in the Caucasus. On September 18, 1739 the Treaty of Belgrade was signed between Russia and Turkey. According to which Russia regained Azov, but with the obligation not to arm it and to dismantle its fortifications. It also received the right to build a fortress on the island of Cherkas on the Don and Turkey received the right to build a fortress at the mouth of the Kuban River. Greater and Lesser Kabarda was recognized as a neutral barrier between Russia and Turkey. The petition of Archbishop Joseph and Archimandrite Nikolai provided information about Ossetians, "these people had been Orthodox Christians since ancient times... As a sign of their ancient piety stone churches with holy icons and books ... and holy fasts are still kept in them. And when on occasion they see a spiritual person, they kindly treat that person and invite that person to their homes for a visit. It was also noted that despite prevalent pagan beliefs, Ossetians still respected Orthodox sacred places and in general were inclined to accept Christianity "and were very capable to obey Christian faith of Greek confession". The problem was the complete absence of "spiritual persons who could sow the word of God in those unenlightened people". Therefore, "they are forced to do only one prayer, looking to heaven". This letter of the Georgian priests ended with a proposal to initiate missionary activities in the North Caucasus: "... would it not be desirable... the above-named people... for preaching the word of God and their baptism to do this God-pleasing work send those who are able and willing to do this". Names of Georgian clergymen that "know their language partly" i.e. know Ossetian language were also mentioned.

@®

Long before the founding of the Ossetian religious commission there had already been educated priests, teachers and common people in Ossetia who could read and write, and who knew languages of their neighbours, including Kabardian and Georgian. An enormous role was played by the Ossetian Spiritual Commission. At the suggestion of Georgian clergymen a coaching inn was built on the territory of Ossetia for them to live there, arrange and maintain a church and a school for Ossetian youth. In 1749 there were 7 boys studying in Ossetian church, they "mechanically read".

Activities of the Russian Orthodox Church intensified in the second half of the XIX century. Realising that any discontent could provoke a popular uprising, the clergy was given the important task of maintaining and developing loyalist and monarchist sentiment. After the Caucasian War, the territory of the North Caucasus became part of Russia, the border was pushed back, but this was not enough and there were many challenges to be met in mastering the new space. Abolishing serfdom and passing a number of laws contributed to intensive settlement of new people.

Various missionary societies and organisations were established in the Caucasus. A.I. Baryatinsky proposed to use means of persuasion and restoration of Christian beliefs and traditions rather than violence and coercion for the more humane development of the land. He proposed not only the building of new churches but also the restoration of ancient ones. He also deemed it expedient to train clergymen speaking Caucasian languages so that they could deliver Christian precepts to highlanders in their native language that they would understand, to translate orthodox literature and most importantly, to make Christianity a protected, not oppressed faith in the mountains. He was a deputy governor of the Caucasus who initiated establishment of "Society of restoration of Orthodox Christianity in the Caucasus".

rests

ар ед ШШЙ№ ицить Ffl ИМПЕРАТОРСКАГО ВЕЛИЧЕСТВА, №ШРЙП Ш1Ш1Щ

ОБЩЕСТВА В03СТАН0ВЛЕН1Я ПШОСШЕМО ШСТ1ШШ ю «маме, ал 1801 годъ.

ОТ^ВТЪ

ОБЩЕСТВА В03СТАН0ВЛЕН1Я

ПРАВОСЛАВНЫХ) ХРИСТ1АИСТВА

НА КАВКАЗА, за 1875 1ч)дъ.

ТИШИ.

Tenrp^i Kucmpi Гшммиктцмшо грииашю ао» и КмшЕ Лорея-Мелмоаи тли, 1 их

H№6rr««ia га*1»к> гор л кипг» меетича «Ш1Э«»лге-

117».

According to the "Charter of the Society of restoration of Orthodox Christianity in the Caucasus" main directions of its work were: construction and maintenance of churches and establishment of premises for clergy; opening of parochial schools for education of mountain youth and financial support for them; translation of Bible, educational and other useful for reading books into native languages and printing of their translations, as well as church-books in Georgian; assistance to Diocesan authorities in fulfilling their propositions; building of parochial schools and kindergartens; creation of small and medium-type schools. The society, acting on the basis of the Greatest approved June 13, 1884, has in its charge parochial schools for the education of the children of city dwellers. The society's Council determines the sums to be allocated for the upkeep of the parochial schools. The amount of aid, over and above the fixed salary, accorded to clergymen, depends on their merit and the discretion of the society. Annual reports shall be submitted to the patroness.

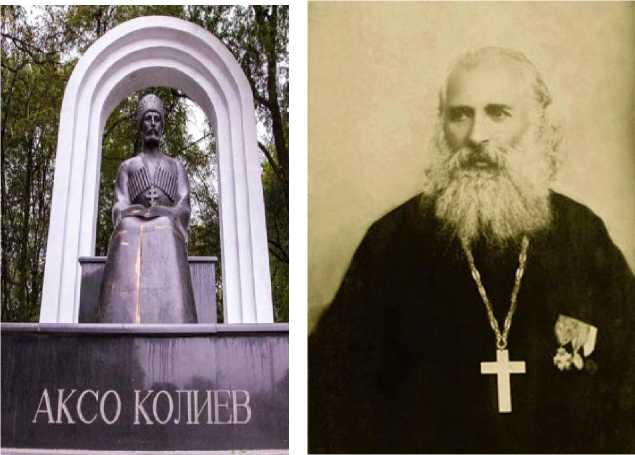

Only graduates of teachers' seminaries and institutes, who were also responsible for the 'moral' state of parents and pupils, could teach in parochial schools. The curriculum of parochial schools included an introduction to the basics of Orthodoxy, a series of general education subjects, and some crafts. Among obligatory disciplines were: "... the Russian language, local languages, arithmetic with the beginnings of geometry, world studies with the beginnings of natural history, geography and history, writing, drawing, secular and church singing, gymnastics, gardening, handicrafts (female schools) or crafts (male schools)". Some parochial schools practiced a method of joint education of Ossetian and Russian children, administration thought that this would help local children to faster learn Russian language and prepare population for "merging into one Russian nation". Staffing was always an acute problem. In March 1887, a missionary religious school was opened in the Ossetian village of Ardon to train clergymen and parish school teachers from the local population. The school could also admit children of "Mohammedan confessions of North and South Ossetia that showed love towards Christianity in order to attract them to it". In eight years the task was not justified, only five out of 39 graduates became clergymen. In August of 1895 the school was transformed into the Alexander Theological Seminary for training of teachers for Ossetian parochial schools. The mid-nineteenth century saw the emergence of a galaxy of outstanding educators, a striking representative of which was Akso Koliev. He was a public figure and priest, thanks to his efforts the translation of religious and church books appeared in rural schools. He was one of the pioneers of women's education. "An educated mother means educated children and an educated child means an educated society" - he believed.

The first Ossetian girls became pupils and went to the primary school, which Akso Besaevich opened at his home and maintained on his own funds. In addition to theology, the curriculum included natural sciences and humanities. By 1880 there were seven female schools where about two hundred girls were studying, many of them later became teachers and gave literacy to new generations of Ossetians. The Vladikavkaz Ossetian religious school, opened in September 1836, promoted growth of book printing and literate population. In the year of its opening there were only 34 pupils, of whom 33 were Ossetians.

The main purpose of this school was to prepare conductors of Christian ideas, priests, missionaries and teachers for parish schools. Every pupil was paid 50 silver Rubles. Great merit was paid to the teacher of the Vladikavkaz Spiritual School Sh. Dvalishvili, inspector and teacher of Russian language G. Mzhedlov and officer P. Zhuskayev for helping academician A. Shegren to compile his "Ossetian grammar". Activities were encouraged by the secular authorities, and families were able to enjoy various benefits. Many representatives of the clergy of the Caucasian Diocese greatly contributed to the rescue and study of ancient Christian monuments in the North Caucasus.

Clergymen stood at the origins of origin of local regional studies and archeology: a great contribution to their development was made by priest Timofeevsky Yevfimi Petrovich. Being a full member of Kuban regional statistical committee, father Evfimi compiled a thorough work "Kholmsk church-parish chronicle or, something else, the story about church-parish life of the inhabitants of Kholmskaya village from the beginning of its existence". He strove to support and develop literacy and enlightenment of the local Cossack and non-resident population. His teaching and organizational activities greatly contributed to the development of regional education. His pastoral, literary and organizational talents were revealed to their fullest extent in the Caucasus. Often he visited remote parishes on his own, without informing the local clergy. It was often thanks to this that he was able to put a stop to numerous cases of negligence in divine services and the lack of the necessary liturgical utensils in churches. The priest was very active in charity events and did his best to help the needy people. Timofeevsky left many handwritten sermons of his own composition. He often published his articles, teachings and conversations in the local "Diocesan Gazette" and newspapers. His writings were always distinguished by their originality, vitality and thoroughness. In his work Mikhailov Nikolai Tikhonovich reports on church schools and the standards of the clergy, and notes the most notable events in the life of the parishes. The topographical position of the settlement, the occupation and degree of economic well-being of the population. The fruit of the research of Archpriest Alexey Gatuev was a complex historical sketch of the history of Christianity in North Ossetia. For many years, Father Alexey was a brilliant teacher of the Law of God in the Vladikavkaz Diocesan Women's School and the Vladikavkaz Olginskiy Women's Gymnasium, paying much attention to school building.

In 1867, Gatuev opened the first rural female parochial school in Salugardan village in Ossetia, where his wife later worked as a teacher. In October 1890, at Holy Trinity Church of the Brotherhood in Vladikavkaz, Gatuev opened a parish school, which was maintained on donations from parishioners and the rector himself. He taught the Law of God, and his daughter Nadezhda taught crafts to female pupils. In the early 90s of the XIX century, Father Alexei opened a parochial school for women at the Church of the Protection of the Holy Mary in Sleptsovskaya village, Sunzha district. Gatuev took part in collecting ethnographic and folklore material. Information collected by him about religious beliefs of Digori people were included in his work "Religious beliefs of Ossetians" which constituted the second part of his famous work "Ossetian sketches". Gatuev also participated in gathering materials on Ossetian language for Ossetian-Russian-German dictionary compiled by W. F. Miller. A significant contribution of Father Alexei Gatuev to Ossetian studies was his historical and ethnographic work. In 1891 the newspaper "Terskiye Vedomosti" published his essay in 12 issues. In 1901 it was published as a separate book in a revised and expanded form.

The priest's book was republished in the "Christian Caucasus" series in 2007. The governmentalisation of religion should be noted: all events were accompanied by a church ceremony, demonstrating the greatness of power. A divine liturgy was an obligatory component of the celebrations. On the birthdays of tsars or on their accession to the throne, for example, "the bells were rung in all the city churches and crowds of people marched to the church squares". A liturgy and prayer service began every event from the opening of educational institutions to various institutions. The Church increased the official component and contributed to the establishment of statehood.

-

IV. CONCLUSION

Thus, it should be noted that the activities of the Russian Orthodox Church in its development has passed a difficult and thorny way, and the formation of the specifics of missionary activity was strongly influenced by both subjective and objective factors, above all the policy of the state and the position of the Church. Missionaries have played a huge role not only in the spread of the Orthodox faith, but also in strengthening the national outskirts and consolidating the position of the state, in solving educational and social problems. We would like to note the necessity of close co-operation of the Church in the region at the present stage of development.

Список литературы The Influence of the Russian Orthodox Church on the Development of Schools and Education in the North Caucasus

- Central State Archive of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, F.12. 7. D. 2 P. 67.

- Central State Archive of North Ossetia-Alania. F. 12. OP. 1. D. 53. L. 64.

- Central State Archive of North Ossetia-Alania. F. 12. OP. 1. D. 53. L. 64.

- Central State Archive of North Ossetia-Alania. F. 1. OP. 1. REP. 17. L. 34-37.

- F.12. OP. V.17, P. 34-37 5. F. 12. op. 1. D. 53. L. 64.

- Archive of the North Ossetian Institute for Humanitarian and Social Research, F. 10. 1. D. 70. L. 13-21

- Archive of the North Ossetian Institute for Humanitarian and Social Research, F. 10, OP. 1, D. 70, P. 13-21 7. 1. D. 70. L. 5

- At the National Archives of the SOIGSI. 10. OP. 1. D. 70. L. 24-25.

- Na SOIGSI. F. 10. OP. 1. D. 71. L. 36.

- At the National Archives of the SOIGSI. 10. OP. 1. D. 74. L. 10

- Belyaev I.I. (1900) Russian Missions to the Outskirts: A Historic Ethnographic Sketch by Archpriest. St. Petersburg. 308 p. (In Russ).

- Blaramberg I.F. (2010) Historical, topographic, statistical, ethnographic and military description of the Caucasus Translation from French. Moscow: Izd. Nadirshin. 400 p. (In Russ).

- Butkov G.P. (1869) Materials for the new history of Caucasus, from 1722 to 1893. Sankt Peterburg: The printery of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. 592 p. (In Russ).

- Gatuev A. (1896) Christianity in Ossetia. Vladikavkaz eparchial bulletin. Vladikavkaz. Pp. 175-176. (In Russ).

- Gatuev A. (1901) Christianity in Ossetia. Vladikavkaz: Printery of V.P.Prosvirnin. 118 p. (In Russ).

- Gedeon, Metropolitan of Stavropol and Baku. (1992) History of Christianity in the North Caucasus before and after its joining Russia. Moscow-Pyatigorsk. 191 p. (In Russ).

- Gostieva L. K. (2014) Archpriest Alexey Gatuev. Orthodoxy in Ossetia. Essays on Orthodox clergy of the second half of XIX - early XX centuries. Vladikavkaz. (In Russ).

- Dubrovin N.F. (1871) History of war and domination of Russians in the Caucasus. Т. 1-6. - St. Petersburg: typ. Dep. of Udelov, 1871-1888. 6 т. Book 1: An Essay on the Caucasus and the Peoples Occupying It. 640 p. (In Russ).

- Efimov A.B. (2007) Essays on the history of missionary work of the Russian Orthodox Church. M.: Publishing house of PSTGU. 688 p. (In Russ).

- Kanukova Z.V. (2016) Orthodoxy in the formation of Russian statehood and all-Russian identity in Ossetia (late XVIII - early XX century). Izvestiya SOIGSI. Nomer 20 (59). (In Russ).

- Krasnov M.V. (1913) Illuminators of the Caucasus. Stavropol.102 p. (In Russ).

- Modzalevsky L. (1880) Teaching business in Caucasian region from 1802 to 1880. Memo book of Caucasian school district for 1880. Tiflis. Part I. Pp. 3-96. (In Russ).

- Mukhanov V.M. (2016) Projects of establishing a missionary society in the Caucasus: from A.P. Yermolov to Prince A.I. Baryatinsky. Russian History. Nomer 3. (In Russ).

- Nemashkalov P.G. (2018) Formation of the Caucasian Eparchy and its role in the life of the North Caucasus in the 1840-s. Stavropol: Stavropol Theological Seminary. 244 p. (In Russ).

- Report of the Society for the Restoration of Orthodox Christianity in the Caucasus in 1864. Tiflis: printing house of the Main Administration of the Viceroy of the Caucasus. 147 p. (In Russ).

- Prozritelev G.N. (1906) Ancient Christian monuments in the North Caucasus. Stavropol: Stavropol. provincial stat. comm. 15 p. (In Russ).

- Totoev M.S. (1957) History of origination of Ossetian writing in XVIII century. Izvestiya SONII. VOL. XIX. Orjonikidze. Pp.135-146. (In Russ).

- Tuayeva B.V. (2004) The role of confessional societies in development of public education in North Caucasus (second half XIX - beginning XX-th centuries). Uspekhi sovremennogo naturistva. Nomer 7. Pp. 96-97. (In Russ).

- Uslar P.K. (1869) The beginning of Christianity in Transcaucasia and the Caucasus. Collection of information about the Caucasian mountaineers. Vol. II. Tiflis: Typography of the Chief Department of the governor of the Caucasus. Pp.1 - 24. (In Russ).

- Tskhovrebova O.D. (2018) History of Education and Development of Pedagogical Thought in Ossetia. Moscow: MAKS Press. 223 p. (In Russ).

- Shikhsaidov A.R. (1957) On the penetration of Christianity and Islam in Dagestan. Uchenye zapiski IYAL Dagfiliala AS USSR. Т. 3, History Series. Makhachkala. Pp. 54-76. (In Russ).