The military revolution of Peter I - quantitative measurement

Автор: Krokosz Pawe, Opatecki Karol

Журнал: Вестник ВолГУ. Серия: История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения @hfrir-jvolsu

Рубрика: К 350-летию со дня рождения российского императора Петра I

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.27, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Introduction. The article is devoted to the analysis of the processes related to the modernization of the Russian army in the times of Peter I. Owing to the magnitude and historical momentousness of these changes, we have introduced the term “revolution” in lieu of the term “reform” used hitherto in historiography. It is significant and noteworthy that these processes took place during the regular frontline military operations of the Great Northern War (1700-1721), when the tsarist army faced the perfectly organized Swedish army. Methods. So far, theories of military revolution and neo-institutional revolution have been deployed to show the transformations taking place at the time. Without denying the previous research findings, we have presented the modernization of the Russian army in the first quarter of the 18th century in quantitative terms. Hence, we have chosen three issues - recruitment, armament, and the number of officers in the army. Not only is there a sufficient source base for these issues, but they also allow for the time function in the ongoing transformations. Results. The figures under scrutiny indicate that the success of these military transformations was largely based on the recruitment system, which was superbly adapted in Russia. This made it possible not only to establish a regular national army of more than 100,000 soldiers, but also to maintain its headcount during the war despite the losses that the army suffered. In this way, almost half a million soldiers were recruited in Russia in the first quarter of the 18th century. The article emphasizes the conditions that had to be met to establish an army that could match the Swedish adversary. A key element was arming the military with modern firearms. Thanks to foreign purchases, primarilyin the Netherlands, the rearmament was completed before 1709. The organizational structure of regiments, battalions, and rotas was also reorganized, so that the appropriate number of officers, non-commissioned officers, and military musicians was adjusted to the total number of soldiers. With the introduction of military discipline, it was possible to reduce the group of officers and musicians from 18.25% (1699/1700) to 10.15% (1711).

Peter i, russian armyin the first quarter of the 18th century, the great northern war (1700-1721), armament of the russian army, recruitment

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149140569

IDR: 149140569 | УДК: 94(470+571)“17”:355.1 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu4.2022.3.14

Текст научной статьи The military revolution of Peter I - quantitative measurement

DOI:

Цитирование. Крокош П., Лопатецки К. Военная революция Петра I: количественное измерение // Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 4, История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения. – 2022. – Т. 27, № 3. – С. 208–221. – (На англ. яз.). – DOI:

Introduction. The term “military revolution” was introduced to historiography by Michaels Roberts in 1955 during his lectures given at Queen’s University in Belfast [28]. The author pointed out huge transformations in martial art of West and Central European states in the years 1560–1660, affecting dramatic reshuffles in the military potential of particular states of the Old Continent. An impulse for the transformations was to be adopting gunpowder for the needs of warfare, and a keystone of the conception was the case of Sweden, which, due to Gustav II Adolf’s reforms (1611–1632), turned from a poor and demographically small country into a power [37].

The main continuer of the theory was Geoffrey Parker, who observed that the technological transformations in the 16th and 17th centuries brought about changes in strategy and tactics (domination of infantry, artillery and bastion fortifications), enlargement of the army (10-time growth of the army between the end of the 15th c. and the end of the 17th c.), as well as the development of bureaucratization and centralization of states [27; 38]. Thereby, previous medieval troops were rapidly transformed in perfect organized armies, for which the state provided victualing, armament, uniforms, etc. The theory triggered a vivid and creative discussion in the circles of military historians. Certain researchers, for example Jeremy Black, John A. Lynn, David A. Parrott, negate the aforementioned establishments [5; 22; 29]. They maintain that the importance of technological achievements in this process was too accentuated. Changes in the tactics and extension of the army in the modern period were of evolutionary nature and manifested no signs of revolution. J. Black emphasized that really revolutionary transformations in the organization of troops, the size of the army, as well as influence on the state structure occurred at the end of the 17th century and at the beginning of the 18th century. This was connected with the states bureaucratic and fiscal adaptation to the needs of the military of those days, where money was the principal factor enabling to conduct wars and maintaining armies. It was then that the model of state supported by the state domain and selfsufficient economy was abandoned in favor of the state supported by taxes [41]. Only this organization guaranteed raising and maintaining enormous, modernly trained, armed and equipped armies.

An approach to military reforms through the prism of the modernization of the whole state seems very close to ours. In the modern period the Russian state took attempts at reforms several times, which was identified with a military revolution, but they were never permanent transformations [30]. Therefore the authors decided to analyze Peter I’s reforms extensively, among which we selected a key element, in our opinion, which is the origins of an enormous, standing modern army. It was based on a new organizational model: recruits conscripted by force, primarily from peasants and burghers, perfectly trained and equipped according to West European models.

Methods. The paper deploys quantitative analysis. On the basis of mass figures compiled and collected by historians, an assessment of the changes occurring in the Russian military during the Great Northern War (1700–1721) was carried out [3; 4; 6; 17; 20; 25; 36]. A core method to describe these phenomena was not only the quantity (number) itself but also a function of time (years elapsed during the war with Sweden). Three key issues were considered in the analysis:

1) recruitment of soldiers; 2) arming them with weapons imported from Western European countries; 3) percentage of officers in army units. This research provides a broader perspective and confronts the findings of historians using other research methods, both traditional and modern, in the context of quantitative analyses [11; 13].

Analysis. The use of local human resources. In our opinion, the new way of recruitment was of decisive importance in the process of the modernization of the Russian army. Both in the 16th and 17th century a remarkable inflow of mercenaries from Western Europe to the Muscovite State was noticeable [24]. Peter I appreciated the foreigners’ experience but for many reasons he was not able to base the core of his army on this group [31, p. 122]. One of the fundamental reasons was a long distance from the main recruitment regions in Europe. Supplementing the forces in the course of the war was very difficult organizationally. Moreover, such a soldier was very expensive [17, pp. 89, 98, 125–132; 36, pp. 156– 157]. The key question, thus, was the appropriate use of own human resources with the use of military experts from Europe 2.

The Muscovite State had experience in this matter from the 1630s, when it started forming so-called regiments “of new organization,” regiments of the “soldier” type, regiments of Reiters and Dragoons, where the core was constituted by Russian men commanded by numerous foreign officers. These units took part in the Polish-Russian War of 1632–1634 (by the end of the war 16 regiments of 17,000 men had been formed), after which they were dissolved. In the subsequent years, depending on the needs, the regiments were recreated, and then, when they were not needed any more, the soldiers were dismissed home [7, pp. 133–154]. The result of these actions, taken because of limited financial capabilities, was creating a semi-regular army, combining European innovations and Russian military traditions. It is worth noting that analogous solutions were applied at exactly the same time in the neighboring Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Also there an identical type of military units were formed, modeled on the West European organization but consisting of its own subjects, partly complemented with foreign officers (primarily German). In this way, beside traditional units (primarily cavalry: Polish Hussars,

Pancernys, Cossacks) called “the national contingent,” there emerged Western type troops called “the foreign contingent” [9, pp. 70, 133].

In the mid-17th c. the units operating by the West European pattern were much better adopted in Poland and Lithuania than in Russia. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, it was a standing army, which replaced the previous infantry units, and in the cavalry, the reforms made it possible to form units of Reiters and Dragoons. It was otherwise in the country of the tsars, where by the 1690s a mixed organizational system of the armed forces was in operation. The core of the infantry were old shooter units enforced by the soldier regiments of “the new organization,” and the cavalry was made up by units formed by noblemen obliged to serve in the army. The forces were traditionally supported by Cossack (Ukrainian and Donian) and Tatar troops.

Peter I, preparing the war with Sweden, decided to completely abandon archaic solutions and base his military force on a professional army based on conscription. Two fundamental stages are noticeable in these actions. One fell on the years 1699–1704 and was characterized by lack of a systematic plan and was conducted on a considerably smaller scale than the second stage of 1705–1710, the culmination of which was the first determination of the whole state of the Russian Army in 1711. The year 1705 turned out crucial, because then the responsibility of providing recruits was transferred from landowners to urban and rural communities [43].

The first draft, announced in 1699, was characterized by a double nature: proclamations invited all so-called “free people” to join the army, guaranteeing an annual pay of nearly 11 rubles as well as alimentation in the same amount as the soldiers in the Preobrazhensky and Semyonovsky Regiments [2, pp. 228–229]. Beside volunteers, subjects belonging to landowners of beneficial estates (pomestie), as well as to clergymen were conscripted. The number of the recruits or the amount of a potential compensational fee was precisely determined. The Moscow and provincial noblemen in war service had to provide 1 infantryman from 50, and 1 cavalryman from 100 farms in their possession. The noblemen serving in central and provincial administration offices, as well as the noblemen not serving because of their old age, as well as widows and minors were to provide 1 recruit from 30 farms. Also the Orthodox Church and monasteries provided recruits from their land estates: one man from 25 farms. In the case of too few farms qualified to provide a recruit, the aforementioned had to pay a fee of 11 rubles [3, pp. 22–23]. Jointly over 32,000 soldiers were recruited, even though primarily twice as many of them were planned to be conscripted [44, pp. 346–347; 45, pp. 343, 451– 452]. These actions resulted in creating 27 regiments of infantry and 2 regiments of cavalry (Dragoons) in 1699 3.

The first conscription was of a joint nature: they recruited both into the infantry and the cavalry. In the subsequent years no permanent rules were developed and conscriptions were held depending on the needs: soldiers were recruited simultaneously into the infantry, the cavalry and the navy, or separately into each of the military specializations. It could happen that within one year three (1705, 1715), four (1711, 1714) or even seven (1706) conscriptions were summoned. Oftentimes old units of infantry and cavalry (dragoons) were dissolved, and new units were formed of the veterans and new recruits. In the subsequent years of the 18th century, conscription was of increasingly oppressive nature. In 1704, Prikaz Pomestny conducted a conscription of peasants from the Moscow district called “poll conscription”. For the first time the army did not take a recruit from the number of farms (smokes) but from the overall number of inhabitants [10, p. 134; 15, pp. 13–39].

In 1705, a new stage connected with recruiting people into the army began. Permanent territorial districts were established, where conscriptions were held; it was also at that time that the conscripted were officially called by the term “recruit” [34, pp. 858–859]. In 1710, the burden of recruitment was transferred onto the governorate authorities (in the Moscow Governorate, the Prikaz for Military Affaris supervised recruitment). Two years later particular units were assigned to particular governorates, which distributed evenly the burden of supporting the troops [34, pp. 858–859].

Basing the military service on Russia’s own subjects was connected with the threat of rebellions. Experiences of the 17th century, when enormous peasant or Cossack uprising broke out, showed that sending veterans home after a fewyear military service may have a very dangerous consequence. Therefore, the service in the army reformed by Peter I was usually for life. It very often happened that front-line soldiers after 20– 25 years of stay in their home units, went to garrison regiments or other auxiliary units [35, p. 83].

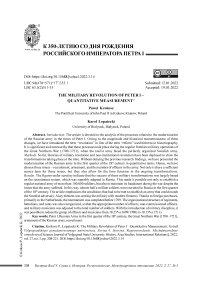

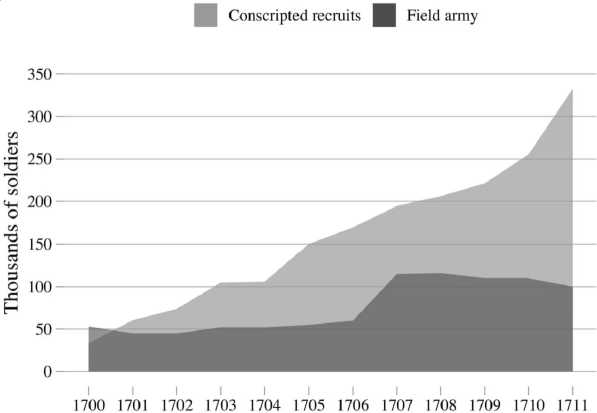

As Evgeny Anisimov informs, and Irina Volkova repeats, by 1711 139,000 men living in Russian villages were recruited to the army [1, p. 154; 47]. It is certainly the data which should be revised. Still not having all calculations, the authors know that by 1705, 150,343 men were recruited in this way. Five years later it was jointly 255,437, in the following years: 381,202 (1715), 422,453 (1720) and nearly half a million in 1724 (Fig. 1). Taking into account the number of soldiers, which in its peak (1707–1708) reached nearly 116,000 men, and from 1711 onwards it stayed within 100,000, the subsequent conscriptions could cause incredulity. In reality, it reflects an enormous rate of own losses: deaths as a result of diseases, injuries, permanent disability, captivity and primarily desertion. This was emphasized by a Swedish auditor, Lars Ehrenmalm, taken prisoner by the Russians in 1709 [4, pp. 307–332]. Desertion occurred as early as the very beginning, along with dispatching new soldiers to the frontline. In the light of fragmentary data, even before reaching the frontline desertion was c. 8– 10%, sometimes even 40% 4. It was a phenomenon known in Europe 5, but the obligation of life service additionally intensified the process.

Over the following years of the Northern War, the authorities wanting to reduce this problem threatened the deserting soldiers with very rigorous punitive measures in the form of corporal punishments, exile to hard works or galleys (including penalties for his family members), not excluding the capital punishment [34, pp. 284, 289, 311, 526–527, 837–838]. The authorities, however, realized that repressions against the deserter would not be effective; therefore they regularly proclaimed amnesty towards the returning deserters [19].

Undoubtedly, after the desertion the greatest losses were caused by spreading diseases; soldiers often died of hunger or because of atmospheric conditions before they reached the battlefield. The Russian army also suffered from painful losses during the most important battles and sieges of the Great Northern War, for example at Narva in 1700, during the siege thereof and of Dorpat in 1704, at Golovchin and Lesnaya in 1708, and foremost a year later at Poltava [12]. Due to the introduction of the conscription system, the Russian army, despite enormous losses in people, was able to secure the number of soldier balanced with the financial abilities of the state (see: fig. 1). For instance, the conscription of 1705 was described by an English envoy, Charles Whitworth, who noted that due to the solutions adopted in Russia at that time 29 new field regiments of infantry were formed. The headcount of each regiment exceeded 40,000 soldiers. [4, pp. 179–189; 40, p. 61] 6.

Fig. 1. Number of recruits conscripted into the Russian Army by 1711 in collation with the nominal state of the field army

Note. Based on: [3, pp. 23–29; 4, pp. 89–309; 25; 34].

Figure 1 confirms the effectiveness of and rationale behind Russia’s self-adopted recruitment system. The solutions known in Western and Central Europe were adapted to the capabilities and specifics of Russia rather than copied. Consequently, the territorially huge and quite populous state (in 1724 Russia had 5,409,930 males burdened with the poll tax [1, p. 101]) guaranteed a supply of soldiers regardless of the situation at the front. The caesura was 1705, when the basic conscription of recruits was introduced, guaranteeing the state authorities convenient solutions in creating an army according to one organizational scheme. Before the conscription system was fully adopted, volunteers were also used, and, which is particularly important, shooters. The tsar did not trust shooter formations, mainly because of their part in conspiracies and rebellions about the state authorities, but still appreciated their combat value. Certain units were dispatched to various Russian towns and to Siberia in order to serve in garrisons. During the war he allowed to form new units. In 1702, when it turned out that an appropriate number of men were missing to form new regiments of infantry, those units were made of former shooters and shooters’ children. If it was possible to create them, they were sent directly to the frontline in order to fill staff shortages of the newly formed units [32, pp. 184–193, 571–572]. In 1704, Peter I was forced to issue an ukase ordering the return of the Moscow shooters and shooters’ children deported to Smolensk; they were to join field infantry regiments and garrisons [34, p. 257].

Introduced at the end of the 17th century and consolidated in 1705, the recruitment system allowed the Russian authorities to field nearly half a million recruits in the first quarter of the 18th century. Figure 2 proves that after the most bloody and devastating campaigns of 1700–1709 ended, the need for recruits not only did not decrease, but increased even more. Between 1710 and 1713, army conscription far exceeded the average multi-year trend of its growth. Seemingly defying logic, this actually demonstrates an important point. Primary human losses in the early modern period were not necessarily the result of ongoing battles and sieges. According to preliminary estimates, they accounted for between 10 and 25% of the overall losses. Desertions, diseases and wounds were a much greater threat to the army’s headcount.

Fig. 2. Estimated number of recruits and volunteers obtained by 1724 Note. Source: [3, pp. 23–29].

In Western Europe, preliminary estimates demonstrate that armies were losing between 2 and 14% of full-time personnel each month.

Thus, seemingly victorious campaigns coupled with the capture of enemy provinces paradoxically led to an even greater need for soldiers. This also shows that the Battle of Poltava, which was victorious for the Russians, and the capture of the eastern provinces from Sweden in 1710, as well as the capture of Finland in the following years were by no means decisive for the outcome of the war; they required an enormous mobilization effort – even greater than at the beginning of the Great Northern War. It was not until 1714–1717 that recruitment ceased, recovering at a rate averaged over the entire period in the last years of the first quarter of the 18th century (see: Fig. 2). In summary, Figures 1 and 2 manifest how large and constant the supply of soldiers enlisted using the conscription system had to be in order to maintain a huge professional army of over 100,000, at least until desertion and losses due to disease were significantly reduced.

Rearming the army. Adaptation of the Russian Army to West European patterns required the introduction of uniform and modern arms in the infantry and the cavalry. The soldiers had to be provided with both firearms and cold steel, as well as a new, well equipped, artillery park. Home production of hand firearms did not satisfy the needs. In the years 1674–1696, in Tula, a leading casting house, 2,000 muskets a year were manufactured, but their products were of considerably lower quality than foreign ones [16, p. 90]. The same was true of arms production in the country’s other casting houses [48]. In the meantime, the looming war with Sweden forced complete rearmament of old units and a necessity of arming new ones.

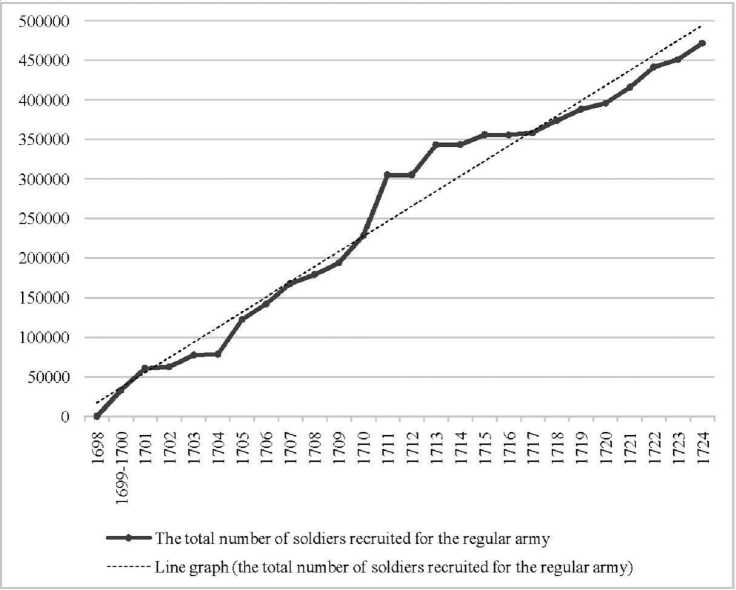

Before Russia gained access to the Baltic Sea, it was the port in Archangelsk that was a place of transfer of the arms bought in Western Europe, primarily in the United Provinces (the Netherlands). In the years 1695–1700 over 30,000 muskets and 10,000 bayonets were imported. The defeat at Narva in 1700 resulted in the loss of artillery and the firearms purchased with so much effort. Then, an energetic Dutch merchant, Johan Lups, offered his assistance, becoming the most important weapon supplier for Russia. At the beginning of the 18th c. he delivered 19,213 rapiers, 67,792 locks for muskets, 7,116 pairs of pistols, 11,546 muskets with bayonets, 750 rifles for dragoons, 3,000 ordinary muskets, 12,098 musket barrels and nearly 20,000 blades for cold steel. The authors are also familiar with expenses in rubles incurred by the tsar’s treasury for arms supplies from Western Europe to Russia in the years 1706–1709. The expenses in subsequent years are as follows: 1706: 54,000; 1707–1708: 176,639; 1709: 44,705 rubles [16, pp. 79–80, tab. 24].

Absolute values for the years 1701–1710 indicate that at that time all soldiers were provided with new arms, usually produced by the Dutch. In that period over 114,000 muskets and 2,700 rifles were purchased, as well as 19,500 pairs of pistols; additionally, 200,000 items of cold steel were imported. Certainly, it is not a complete list, since the process connected with own production, inflow of foreign weapons as well as their losses was characterized by dynamics. On the one hand, part of the armament was destroyed, another part was taken over by the enemy, or was taken by deserters. On the other hand, a certain number of arms were spoils of war 7. In this context it is important to accentuate the extension of domestic metallurgic industry. Over time, these actions had an impact on the reduction of dependence on foreign supplies. The growth of manufactures producing arms, combined with the raising quality of the production in 1705 resulted in the production of 20,000 tons of cast iron (10 times more than at the beginning of the 18th c.) and 3,600 tons of copper. The reorganization of factories in Tula resulted in their ability in 1715 to produce 11,000 muskets, 7,000 rifles and 8,000 pistols. From the beginning of the Great Northern War till the end of 1717, they altogether produced 64,000 items of fire arms [16, p. 92].

The analysis of Figure 3 shows the complexity of the phenomenon. Beside the purchase of whole arms, also modern flintlocks were imported (Marin le Bourgeoys’ construction), which determined the superiority of the new fire arms over the old ones [23, fig. 17]. Their installation in older models meant that the rearmament of the army occurred already in 1706. Thus, we deal with a spectacular action, which enabled, in six years, to create an army of over 100 thousand men equipped with new locks, and within nine years in new arms. The gravity of the transformations can be understood referring to medieval haplology. Polish studies demonstrate that rearmament of knights occurred on average every 70 years (1290, 1360, 1430 and the turn of the 16th c.). It was an effect of experience acquired in military campaigns, and, of course, the change dynamics during the military revolution was much faster. The example of Peter I’s army shows that rearmament of even enormous masses of soldiers could be conducted even eight times faster than in the Middle Ages.

The whole army, on the other hand, including garrison units, was rearmed around 1711. Then the authorities determined a new number of soldiers in the regiments of the frontline infantry, as well as in garrisons and the cavalry. In accordance with the adopted guidelines, the army was to consist of 85 regiments of infantry: 42 frontline and 43 garrison, as well as 33 regiments of cavalry (including 3 grenadier regiments formed as early as 1709). The infantry was to consist of even 120,000 (frontline infantry: 62,454; garrison infantry: 58,000), and the cavalry of 43,824 soldiers [34, pp. 590–621]. Also the process of modernization of the old arms is visible, which involved exchanging the locks in old types for flintlocks (Fig. 3).

When the saturation of arms was high, they began to think about their unification – the characteristics of the arms imported from abroad was different from the arms produced in Russian factories or captured from the enemy. This state of affairs reduced the effectiveness of the army; therefore, in 1715 the authorities imposed the standardization of the arms used in particular units. Their particular types had strictly specified tactic and technological parameters including: caliber, length of the barrel, length of the whole, weight of the bullet and the load, shot range, fire speed, type of the lock [3, p. 95].

^^^^^м muskets and rifles ^^^^^M cold steel musket locks ^^^^^ number of Russian field troops

1701 1702 1703 1704 1705 1706 1707 17 08 1709 1710

Fig. 3. Arms export from Western Europe to Russia in the years 1701–1710 Note. Source: [14, p. 83].

Reorganization of military units. During the long lasting modernization of the tsar’s army both the general number of units of particular arms, as well as their internal organization were subject to changes. The new type of the army required adjusting to them from the tactic units. As a result of the first conscription in 1699, infantry and cavalry (dragoons) soldiers who were dispatched to Narva in 1700 were divided into three divisions or generalities. They were headed by generals: Avtamon Golovin, Adam Weyde and Prince Nikita Repnin. The new entities were not standardized, so they show a transition stage of the changes in progress. They differed in the number of regiments, the number of soldiers and the internal division of the regiments into battalions and rotas [15, pp. 20–30].

The regiments directly under the command of General Repnin and General Weyde were divided into 3, and Golovin’s into 4 battalions. In the divisions of Golovin and Weyde, the regiments of 1,200 men were to be divided into 12 fusilier rotas (this division became a determinant while forming new units in subsequent years). The situation was different in Prince Repnin’s division, where the regiments were divided into 8 fusilier rotas and 1 grenadier rota, at the composition of the unit between 1,000 to 1,100 soldiers, whereas the sources have no information about the number of the commanding staff. Also the number of two dragoon regiments was diverse and was, respectively, 996 and 800 men [45, pp. 465–468].

In the years 1703–1704 the line regiments were reformed and reduced to 10 fusilier rotas, at the division of the unit into 2 battalions, although there occurred 3-battalion regiments. In 1704 a new regulation entered into force, which determined the number of soldiers in the regiment as 1,364 persons, reducing simultaneously the number of rotas to 8 fusilier rotas and 1 grenadier rota. However, it was not a rule, since alongside there were still units of 10 rotas: certain regiments were divided into 3 (the forces given under the command of the Austrian Field-Marshal Georg Ogilvy, who joined the tsar’s service), and the others into 2 battalions [20, p. 24]. Further changes occurred about 1707, when at the division of the regiment into 2 battalions, the regiment was reduced to 1,348 men, and divided into 7 fusilier rotas and 1 grenadier rota. In 1708 the regiment grenadier rotas were liquidated (except the

Ingermanland and Astrakhan Regiments), out of which the tsar ordered to create completely separate grenadier battalions in the number of 6, with mixed commanding staff: foreign and Russian [33, p. 183]. The battalions made up an ovule of future independent grenadier regiments. In the same year 3 or 4 such units were formed, and in the following years subsequent units [46].

In 1711 line infantry regiments were to include 1,487 men (1,242 of line soldiers and 245 non-line soldiers), and a garrison regiment 1,483 members of the crew. In cavalry it was 1,328 men (1,040 line soldiers and 288 non-line). The units were allotted military equipment and an appropriate number of horses (mounts for the cavalry and draft animals used by the artillery and the wagon fort) [34, pp. 590–621]. The division of the line infantry regiment into 8 rotas (including 1 grenadier rota) and 2 battalions 8 remained intact; analogously grenadier regiments were divided [33, pp. 590–621, 787]. Furthermore, the cavalry (dragoon) regiment consisted of 10 rotas: 9 fusilier rotas and 1 grenadier rota (from 1704 onwards), and was divided into 5 squadrons 9. In 1716 the division of infantry regiments (line and garrison) into 2 battalions 4 fusilier rotas in each was confirmed. Grenadier regiments, on the other hand, had no established organization, because depending on the needs they were divided into 2 or 3 battalions. In 1724 another change took place and the headcount of the line infantry regiment was determined as 1,260 men [3, p. 41] 10. The cavalry line regiment was to consist of 1,253 soldiers [14, pp. 26, 36].

If we analyze the general changes in military units, we can see a clear tendency of increasing the size of the regiment from 1,000 men in 1699 to 1,487 men, which was achieved in 1711. Simultaneously, the number of rotas in the regiment decreased; those units became larger. Dividing the soldier by the number of the rotas, the result is c. 100 people in 1699, which increased to, on average, 151 in 1704 and 168 in 1707. Finally, the highest level it reached in 1711, when one rota had 185 men. We can observe a clear trend to increase the units. Regiments increased their sizes by 49%; similar tendencies can be observed in rotas. Battalions had originally 400 men, and then the number grew to, on average, 546 (1704), 674 (1707) and 747 men (1711): the increase by 86.75%. It should be noted that the planned manning of individual units was frequently incomplete; yet, in all European armies it was a crucial factor in determining the size of the entire army [8].

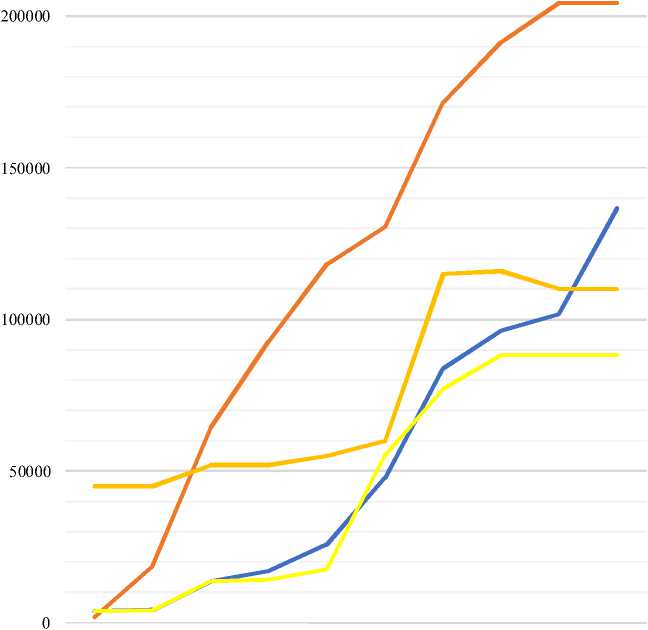

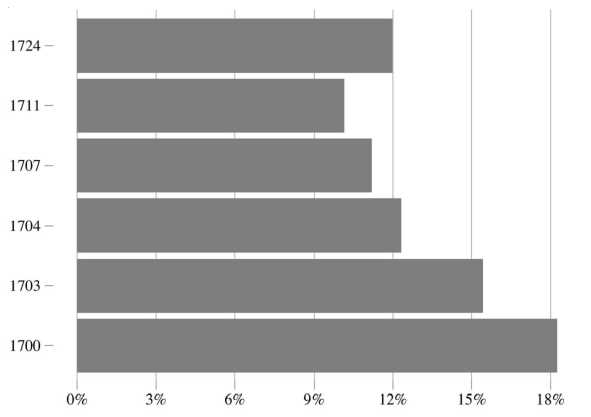

What was the sense of the aforementioned transformations? The firepower of single units increased, even though it had to affect negatively their mobility. Of key importance, however, was the fact that a large units had proportionally fewer officers and more regular soldiers. The cost of maintenance of such units was considerably lower, and their firepower relatively stronger. Nominally, the colonel’s staff consisted of 15 people, and in the infantry rota were 17 officers, noncommissioned officers and signalers [15, pp. 172–174, 338]. As a rule, there was a radical reduction of the number of officers, noncommissioned officers and signalers in the army staff. The ratio fell from 18.25% in 1700 to 15.42% (1703), 12.32% (1704), 11.2% (1707) reaching merely 10.15% in 1711 (Fig. 4). Certainly, in reality the ration was higher, since it was rare for a regiment to achieve its target number (primarily due to desertions), but proportions were similar. This tendency brought about the reduction of maintenance costs 11. A considerable percentage of officers were necessary at the moment of creating new units, whereas along with the acquired experience, both among regular soldiers, and officers, the growth in discipline and sills a gradual process of reorganization was possible 12. The authors think that the organizational transformations were adjusted to the experience acquired during wars against Swedish, Polish and Turkish troops.

In turn, in the inter-war period (1724) the regiment organization enabled a permanent employment of a higher number of officers, which potentially allowed for using them later.

Results.

-

1. In the opinion of the authors of this paper, the key element of the Russian armed forces reorganization was a decision to base the army on Russia’s own subjects (Cf.: [18, pp. 252–255]), who were forcibly conscripted to serve practically for life. Due to the enormous territory and relatively high number of population, regardless of the military situation, the state authorities could safely carry out subsequent conscriptions. From the first conscription at the turn of 1700 till the year 1724, nearly half a million men were recruited in this way. The highest dynamics fell on the first period, by 1705: 150,000 were conscripted, in the following periods the numbers were 255,000 (1710), 381,000 (1715) and 422,000 (1720; see: Fig. 2).

-

2. The scale of the recruitment demonstrates a great organizational (bureaucratic), social and military effort connected with maintaining the army’s potential. After the end of the Great Northern War, the troops of particular arms still remained under arms, and their number was slightly reduced. In 1720 the joint state of infantry was 54,560 frontline soldiers and 3,396 nonfrontline soldiers: 2 guard regiments, 5 grenadier regiments, 35 infantry regiments and 1 battalion

Fig. 4. Percentage of officers, noncommissioned officers and signalers in Russian Army regiments in 1700–1724 Note. Based on: [17].

-

3. The number of recruited soldiers obviously exceeded many times the establishment of the army which was in 1707 c. 100,000 – 110,000 soldiers (see: Fig. 1). This resulted, in our opinion, from enormous personal losses, and it is doubtful that the soldiers killed during field operations constituted a key factor. A much more serious problem was indirect effects of war: diseases, famine, cold, and foremost desertions, which in Russia took dramatic numbers (before the troops reached the frontline, the losses were 8–10%).

-

4. The organization and facilities of the recruitment, without providing modern armament of the army would have turned out ineffective. Regardless of increasing production potential (artillery, firearms and cold steel), modern arms were regularly imported from Western Europe. By 1710 it was over 200,000 items of cold steel, almost 137,000 items of firearms and 88,000 flintlocks for muskets and rifles. Probably a full reequipping of the field army in modern arms occurred as early as 1709; taking into account the purchase of flintlocks, a possibility of adopting old arms to new solutions took place already in 1706. We can observe then, than the equipment with modern arms occurred (depending on the calculating method) within six/nine years. This shows the dynamics of the changes; in the Middle Ages it occurred c. every 70 years. The military revolution gave the process a new dynamics (see: Fig. 3). It is also important to show a correlation of the full rearmament of the army with the victorious battles of Lesnaya (1708) and Poltava (1709).

-

5. Along with the origin of the new army, also military units were reorganized. They were adjusted to new circumstances connected with recruitment and warfare. In the years 1699–1700 a certain organizational chaos could be observed; each division/generality had a different structure and number. The changes initiated in the following years were frequent and complex. As it seems, it

was not until 1711 that the optimum was achieved. According to our observation, there was a clear tendency of reducing the number of officers in units. Such changes reduced the costs of a unit maintenance, and simultaneously increased its combat mobility. The success of the reforms was secured by officers and soldiers acquiring experience as well as enhancing military discipline and morale. Whereas at the beginning of the modernization of the army the number of officers, noncommissioned officers and signalers could nominally reach 18.25%, in subsequent years systematically fell to 15.42% (1703), 12.32% (1704), 11.2% (1707) and 10.15% (1711). After the end of the war we observe a reverse tendency, i.e. the increase of the percentage of officers, which was also a deliberate action, allowing for employing valuable commanding personnel full time during the peacetime (1724; see: Fig. 4).

(the number of frontline soldiers grew at the cost of non-frontline soldiers) [8, p. 140] 13. The solutions developed then survived in its fundamental core until World War I, while the recruitment system became the main burden in the public perception. Beside bureaucratic-fiscal processes, we perceive in this element a fundamental impact of the military revolution on the government structures.

NOTES

-

1 The article came to existence within the framework of the research project of the National Center of Science SONATA, no. 2016/23/D/HS3/03210 entitled: “Military Revolution As a Factor Modernizing Finances and Organization of the Polish-Lithuanian State Against the European Background”.

-

2 In the years 1700–1711 the vast majority of higher commanders (including generals) were foreigners (in 1708 even 76%). Over time, especially from 1709 onwards, their place was taken by Russian officers having acquired war experience [6, p. 706].

-

3 According to Kirill Tatarnikov even until 1730 the Russian army did not have regiments of line cavalry, the tasks of which were fulfilled by dragoons or “mounted infantry” [42, p. 22].

-

4 In 1705 in a group of 2,277 soldiers 895 (39.3%) deserted, five years later 2,835 (37.9%) out of 7,485 escapted. Lower rates of desertion come from the years 1707 (9.7% out of 1,766 men) and 1708 (8.3% out of 11,733 men) [3, p. 29]. According to Viacheslav Tikhonov, in some cases the desertion rate was even higher than 50% [43, p. 29].

-

5 Desertion in regular circumstances meant losses of 10–20% of soldiers. Sometimes, however, they were much higher; for example, in the army of Saxony in the years 1717–1728 every third soldier deserted.

-

6 The data provided by the both foreigners were not far from the facts, since according to the two conscriptions of 1705, jointly 44,539 soldiers went to the infantry units. The possibility of simultaneous use

of a diverse source base, diaries and official statistics to prepare this type of information is acknowledged by Western European military historians, including John A. Lynn [21, pp. 35–37].

-

7 Liubomir Bieskrownyj observed that they decided to preserve pikes in the army. In 1707, on the tsar’s order, even 35,000 items were to be prepared [3, p. 76].

-

8 In 1712 r. the tsar issued an ordinance that the infantry regiments: Moscow, Kiev and Narva, did not change their previous division into 2 battalions. However, the Ingermanland regiment was still to be divided into 3 battalions [34, p. 791].

-

9 In cavalry even 24% of the unit establishment was made up by logistics. In 1720 this dependence fell to 18% [39, p. 108].

-

10 Also the number of non-frontline soldiers was reduced from 17% to 14% in relations to line soldiers of an infantry regiment.

-

11 17 officers and signalers in a rota obtained 66 portions of soldier’s payment rate; on average 3.9 portions fell on one person, whereas soldiers in the infantry regiment staff (15 people) received 143 portions (one person received the payment for 9.5 privates).

-

12 As the example of the Battle of Narva (1700) showed, even the enormous, over an 18% group of officers and noncommissioned officers were not able to control the dissatisfied soldiers [26, pp. 56–57].

-

13 To compare, in 1717 the neighboring Commonwealth introduced financial and military reforms, which were to maintain the establishment at the level of 24,000 soldiers (18,000 in the Crown and 6,000 in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania), and 5.5 m zlotys were allocated for the army, which made 64.6% of the whole budget (5.9 and 2.3 m zlotys).

Список литературы The military revolution of Peter I - quantitative measurement

- Anisimov E.V. Podatnaia reforma Petra I. Vvedenie podushnoi podati v Rossii 1719-1728 gg. [The Tax Reform of Peter I: The Introduction of the Poll Tax in Russia 1719-1728]. Leningrad, Nauka Publ., 1982. 296 p.

- Avtokratov V.N. Voennyi prikaz: (K istorii komplektovaniia i formirovaniia voisk v Rossii v nachale XVIII v.) [Military Order (Issues of Recruitment and Forming Troops in Russia at the Beginning of the 18th Century)]. Poltava. K 250-letiiu poltavskogo srazheniia: sb. st. [Poltava. To the 250th Anniversary of the Battle of Poltava. Collection of Articles]. Moscow, Izd-vo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1959, pp. 228-245.

- Beskrovnyi L.G. Russkaia armiia i flot v XVIII veke (Ocherki) [Russian Army and Navy in the 18th Century (Essays)]. Moscow, Voennoe Izdatel'stvo Ministerstva oborony Soiuza SSR, 1958. 648 p.

- Bespiatykh Iu.N. Inostrannye istochniki po istorii Rossii pervoi chetverti XVIII v. (Ch. Uitvort, G. Grund, L.Iu. Erenmalm) [Foreign Sources on the History of Russia in the First Quarter of the 18th Century. (Ch. Whitworth, G. Grund, L.J. Ehrenmalm)]. Saint Petersburg, Russko-Baltiiskii informatsionnyi tsentr BLITs, 1998. 480 p.

- Black J.A. Military Revolution? Military Change and European Society, 1550-1800. London, Atlantic Highlands, NJ, Humanities Press, 1991. 128 p.

- Chernikov S.V. Evoliutsiia vysshego komandovaniia rossiiskoi armii i flota pervoi chetverti XVIII veka: k voprosu o roli evropeiskogo vliianiia pri provedenii petrovskikh voennykh reform [Evolution of Russia's Military Command During the First Quarter of the Eighteenth Century. The Role of European Influence in the Implementation of Peter's Reforms]. Cahiers du monde russe, 2009, vol. 50, no. 2-3, pp. 699-735. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/monderusse.9914

- Chernov A.V. Vooruzhennye sily Russkogo gosudarstva v XV-XVII vv. [The Armed Forces of the Russian State in the 15th - 17th Centuries]. Moscow, Voennoe izdatelstvo Ministerstva vooruzhennykh sil Soiuza SSR, 1955. 224 p.

- Davies B. Empire and Military Revolution in Eastern Europe: Russia's Turkish Wars in the Eighteenth Century. London, New York, Continuum Publishing Corporation, 2011. 288 p.

- Davies B. Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 1500-1700. London, New York, Routledge, 2007. 256 p.

- Doklady i prigovory sostoiavshiesia v Pravitelstvuiushchem Senate v tsarstvovanie Petra Velikogo, izdannye imperatorskoi Akademei nauk [Reports and Sentences Held in the Ruling Senate in the Reign of Peter the Great, Published by the Imperial Academy of Sciences]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiia Imperatorskoi Akademii nauk, 1880, vol. 1. 501 p.

- Fogel R.W. The Limits of Quantitative Methods in History. The American Historical Review, 1975, vol. 80, pp. 329-350.

- From P. Katastrofen vid Poltava. Karl XII: s ryska fälttäg 1707-1709. Lund, Historiska Media, 2007. 432 p.

- Guzowski P., Poniat R. Miejsce badan kwantytatywnych we wspolczesnej historiografii polskiej. Roczniki Dziejöw Spoiecznych i Gospodarczych, 2013, no. 73, pp. 243-255.

- Ivanov P.A. Obozrenie sostava i ustroistva reguliarnoi russkoi kavalerii. Ot Petra Velikogo do nashikh dnei [Review of Devices and Regular Russian Cavalry. From Peter the Great to the Present Day]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiia N. Tiblena i Ko, 1864. 354 p.

- Kodeks wojskowy Piotra Iz 1716 roku. Krakow, Oswiçcim, Wydawnictwo NapoleonV, 2016. 372 p.

- Kotilaine J. In Defense of the Realm: Russian Arms Trade and Production in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Century. Military and Society in Russia. Leiden, 2002, pp. 67-95.

- Krokosz P. Rosyjskie siiy zbrojne za panowania Piotra I. Krakow, Wydawnictwo Arcana, 2010. 427 p.

- Krotov P.A. «Do Boga vysoko, do tsaria daleko»: pravoslavnyi liud kak glavnaia predposylka uspekha gosudarstvennoi reformy Petra Velikogo ["God is Too High from Here and the Tzar is Too Far to Ear": Orthodox People As the Main Precondition of Success of State Reform of Peter the Great]. Mavrodinskie chteniia 2018: materialy Vseros. nauch. konf., posviashch. 110-letiiu so dnia rozhdeniia prof. Vladimira Vasilevicha Mavrodina [Mavrodinskie Reading 2018. All-Russian Scientific Conference Dedicated to the 110th Anniversary from the Birthday of Vladimir Mavrodin]. Saint Petersburg, 2018, pp. 252-255.

- Kutishchev A.V. Dezertirstvo v evropeiskikh armiiakh v epokhu Liudovika XIV i Petra Velikogo [Desertion in European Armies in the Age of Louis 14th and Peter the Great]. Istoricheskie, filosofskie, politicheskie i iuridicheskie nauki, kulturologiia i iskusstvovedenie. Voprosy teorii i praktyki [Historical, Philosophical, Political and Legal Sciences, Cultural Studies and Art History. Questions of Theory and Practice], 2018, no. 4, pp. 41-45.

- Leonov O.G., Ulianov I.E. Reguliarnaia pekhota 1698-1801: boevaia letopis, organizatsiia, obmundirovanie, vooruzhenie, snariazhenie [Regular Infantry 1698-1801: Combat Chronicle, Organization, Uniform, Armament, Equipment]. Moscow, TKO AST Publ., 1995. 296 p.

- Lynn J.A. Giant of the Grand Siècle. The French Army, 1610-1715. Cambridge, University of Cambridge, 1997. 651 p.

- Lynn J.A. The Evolution of Army Style in the West. International History Review, 1996, vol. 18, pp. 505-545.

- Makovskaia L.K. Ruchnoe ognestrelnoe oruzhie Russkoi Armii kontsaXIV-XVIII veka [Hand firearms of the Russian Army of the End of the 14th -18th Centuries]. Moscow, Voenizdat Publ., 1992. 248 p.

- Malov A.V. Komandnyi sostav chastei soldatskogo, reitarskogo, dragunskogo i gusarskogo stroia ot poiavleniia ikh v Rossii do rospuska posle okonchaniia Smolenskoi voiny. 1628-1636 gg. [Commanders of the Units of New Organization in the Years 1628-1632 (From Preparations for the Smolensk War up to the Dissolution of the New Organization Units Thereafter)]. Tri daty tragicheskogo piatidesiatiletiia Evropy (1598-1618-1648): Rossiia i Zapad v gody Smuty, religioznykh konfliktov i Tridtsatiletnei voiny [Three Dates of the Tragic Fifty Years of Europe (1598-1618-1648): Russia and the West During the Time of Troubles, Religious Conflicts, and the Thirty Years' War]. Moscow, IVI RAN Publ., 2018, pp. 221-238.

- Miliukov P. Gosudarstvennoe khoziaistvo Rossii vpervoi chetverti XVIII stoletiia i reforma Petra Velikogo [The State Economy of Russia in the First Quarter of the 18th Century and the Reform of Peter the Great]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiia M.M. Stasiulevicha, 1905. 702 p.

- Nefedov S.A. Petr I: Blesk i nishcheta modernizatsii [Peter I: Shine and Poverty of Modernization]. Istoricheskaia Psikhologiia i Sotsiologiia Istorii [Historical Psychology and Sociology], 2011, no. 1, pp. 48-73.

- Parker G. The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800. Cambridge, University of Cambridge, 2011. 493 p.

- Parker G. The "Military Revolution" 1955-2005: From Belfast to Barcelona and The Hague. The Journal of Military History, 2005, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 205-209.

- Parrott D.A. Strategy and Tactics in the Thirty Years' War: The "Military Revolution". The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe. Boulder, Westview Press, 1995, pp. 227-252.

- Paul M.C. The Military Revolution in Russia, 1550-1682. The Journal of Military History, 2004, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 9-45.

- Penskoi V.V. Armiia Rossiiskoi imperii v XVIII v.: vybor modeli razvitiia [The Army of the Russian Empire in the 18th Century: The Choice of a Development Model]. Voprosy istorii [Questions of History], 2001, no. 7, pp. 119-136.

- Pisma i bumagi imperatora Petra Velikogo [Letters and Papers of Emperor Peter the Great]. Saint Petersburg, Gosudarstvennaia tipografiia, 1889, vol. 2. 812 p.

- Pisma i bumagi imperatora Petra Velikogo [Letters and Papers of Emperor Peter the Great]. Saint Petersburg, Gosudarstvennaia tipografiia, 1900, vol. 4. 519 p.

- Polnoe sobranie zakonov Rossiiskoi imperii [Complete Collection of the Laws of the Russian Empire]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiia II Otdeleniia Sobstvennoi Ego Imperatorskogo Velichestva Kantseliarii, 1830, vol. 4. 890 p.

- Porfirev E.I. Petr I - osnovopolozhnik voennogo iskusstva russkoi armii i flota [Peter I -Founder of the Military Art of the Russian Regulary Army and Fleet]. Moscow, Voennoe izdatelstvo Voennogo Ministerstva Soiuza SSR, 1952. 288 p.

- Rabinovich M.D. Sotsialnoe proiskhozhdenie i imushchestvennoe polozhenie ofitserov reguliarnoi russkoi armii v kontse Severnoi voiny [The Social Origin and the Ownership of Property of the Officers of the Regular Russian Army at the End of the Northern War]. Rossiia v period reform Petra I [Russia During the Reforms of Peter I]. Moscow, Nauka Publ., 1973, pp. 133-171.

- Roberts M. GustavusAdolphus. A History of Sweden. London, New York, Toronto, Longmans Green and Co, 1953, vol. 1. 63 p.

- Roberts M. The Military Revolution, 15601660. The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe. Boulder, Westview Press, 1995, pp. 13-36.

- Russkaia voennaia sila. Ocherk razvitiia vydaiushchikhsia voennykh sobytii ot nachala Rusi do nashikh dnei [Russian Military Force. Essay on the Development of Outstanding Military Events from the Beginning of Russia to the Present Day]. Moscow, Tipo-Litografiia I.N. Kushnereva i Ko, 1890, vol. 6. 220 p.

- Sbornik Imperatorskogo Russkogo Istoricheskogo Obshchestva [Collection of the Imperial Russian Historical Society]. Saint Petersburg, 1886, vol. 50. 580 p.

- t'Hart M., Brandon P., Sánchez R.T. Introduction: Maximising Revenues, Minimising Political Costs - Challenges in the History of Public Finance of the Early Modern Period. Financial History Review, 2018, vol. 25, Special Issue, no. 1, pp. 1-18.

- Tatarnikov K.V. Russkaia polevaia armiia 1700-1730. Obmundirovanie i snariazhenie [The Russian Field Army 1700-1730. Uniforms and Equipment]. Moscow, Liubimaia kniga Publ., 2008. 352 p.

- Tikhonov V.A. Rekrutskaia sistema komplektovaniia russkoi armii v 1705-1710 g. [Recruiting System in the Russian Army in 1705-1710]. Elektornnyi zhurnal «Vestnik Moskovskogo gosudarstvennogo oblastnogo universiteta» [Electronic Journal Bulletin "Bulletin of Moscow State Region University"], 2012, no. 4, pp. 28-36.

- Ustrialov N.G. Istoriia tsarstvovaniia Petra Velikogo [The History of the Reign of Peter the Great]. Saint Petersburg, Tip. II-go Otdeleniia Sobstv. Ego Imp. Vel. Kantseliarii, 1858, vol. 3. 662 p.

- Ustrialov N.G. Istoriia tsarstvovaniia Petra Velikogo [The History of the Reign of Peter the Great]. Saint Petersburg, Tip. II-go Otdeleniia Sobstv. Ego Imp. Vel. Kantseliarii, 1863, vol. 4, no. 2. 706 p.

- Vasilev A.A. O sostave russkoi i shvedskoi armii v Poltavskom srazhenii [On the Composition of the Russian and Swedish Armies in the Battle of Poltava]. Voenno-istoricheskii zhurnal [Military History Journal], 1989, no. 7, pp. 62-67.

- Volkova I.V. Voyennoye stroitel'stvo Petra I i peremeny v sisteme sotsial'nykh otnosheniy v Rossii [Military Construction of Peter I, and the Changes in the System of Social Relations in Russia]. Voprosy istorii [Questions of History], 2006, no. 3, pp. 35-51.

- Zaozerskaia E.I. Manufaktura pri Petre I [Manufactory Under Peter I]. Moscow, Leningrad, Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1947. 190 p.