"The old man of the sacred town": ancient and recent representations of a bear-like deity from the Lower Ob, Northwestern Siberia

Автор: Baulo A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145257

IDR: 145145257 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2016.44.2.118-128

Текст статьи "The old man of the sacred town": ancient and recent representations of a bear-like deity from the Lower Ob, Northwestern Siberia

The bear has been one of the most popular characters in metal artwork and graphic art of the peoples living in the north of Western Siberia from the Early Iron Age to the present day. On the one hand, this popularity is associated with the perception of the bear as a powerful and dangerous animal, and on the other hand with reverence to the bear as a wise and mighty deity in the mythological context. In the view of this author, these positions do not often agree. Essentially, the bear-deity and the bear-prey were different beings both for the ancient and modern indigenous peoples of the Siberian North, which can be seen from the analysis of cast and graphic representations of the animal. The following hypothesis can be offered: the bear-deity was portrayed standing in full height, while all other variants of bear representations, in side view or in the so-called sacrificial, sacred, or ritual posture (with the bear’s head between its front paws), refer to the bear as prey. This hypothesis is based on archaeological and ethnographic materials from the Lower Ob region, where the bear-like deity was revered by the Ob Ugrians.

“The Old Man of the Sacred Town”: territory and worship

Yalpus-oyka (Mansi language) / Em-vozh-iki (Khanty language), “the Old Man of the Sacred Town” (bear), is a mythical ancestor of the Por phratry. The core of the phratry was the pre-Ugrian (the Ural) population of the Ob region (Chernetsov, 1939: 29). The Mansi and Khanty regard the bear as the descendant of a celestial deity, the spirit-patron, the mythical, historical, and cultural hero, the assistant spirit of the shaman, the guardian of the oath, the keeper of the border between the Middle and the Lower Worlds, etc. (Schmidt, 1989a).

The center of Em-vozh-iki worship (the village of Vezhakary on the Ob River) was widely known throughout the 18th–20th centuries. According to a legend, Yalpus-oyka killed a mighty warrior and buried his horse in standing position; thus there emerged “the horse town of the Old Man of the Sacred Town”, where the winner settled (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 147). Em-vozh-iki lives “on the abundant great Ob, in its middle, where a great town stands in the image of a horse’s neck, a glorious town stands in the image of a horse’s mane” (Moldanov, Moldanova, 2000: 73).

The Mansi and Khanty believed that Yalpus-oyka helped the sick, and they offered bloody sacrifices to him. On the Northern Sosva and the Upper Lozva rivers, he was offered a black scarf in the case of insomnia or “heaviness”. The Mansi had the concept of a “shadow soul”; when it goes away, the person experiences loss of sleep or illness. In this case, using the help of Yalpus-oyka, the shaman might return the “shadow soul” (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 147). It was believed that the Em-vozh-iki helped women in childbirth. He is quick, he could make it everywhere, to all the villages; he can pass through all places, he is said to be a flying god. People most often turn to Em-vozh-iki; he does not waste time, he does everything more quickly and decisively (E.D. Sambindalova, the village of Pashtory, Beloyarsky District, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra) (Baulo, 2002: 9).

The so-called bear festivals are widely known and important rituals of the Ob Ugrians. Once they were not universally celebrated, which was due to the difference in the ideologies of the Ugric phratries, but gradually bear festivals penetrated into the areas where they had not been previously common (Konda, Pelym). Public games were organized not only in connection with the capture of a bear, but also in front of bear skins of animals which had been killed long before. Yalpus-oyka was represented in the form of a bear; it was believed that he was a quick and kind hero helping people to extend their life (Chernetsov, 1968; Rombandeyeva, 1993: 62; Moldanov, 1999: 125; and others).

The Hungarian scholar Eva Schmidt identified the primary (early) area of worshipping “the Old Man of the

Sacred Town”, which stretched along the right bank of the Ob River from the present-day village of Oktyabrskoye in the south to the village of Vanzevat in the north, and the secondary (later) area, located, in her view, in the basin of the Northern Sosva River upstream from the village of Igrim to the village of Verkhneye Nildino (Schmidt, 1989b: 11, fig. 3).

The primary area of the bear cult was of great mythological importance to the Ob Ugrians. According to the beliefs of the Northern Khanty, there were two main periods in the origin of the Earth: the first, “when they created the land; when they created the water”, and the second, “when they divided the land, when they divided the water”. In the second period, the children of the celestial god Torum were taken down to Earth, and the whole Earth was divided between them. Each of them became a guardian spirit in his land. It was believed that the place from where the children of Torum went out to their lands was not far from the village of Tugiyany*. This place is called “the land divided by the seven verts **, the land, divided by the six verts ” (Mifologiya khantov, 2000: 239) or “the land where the seven gods were distributed” (Slepenkova, 2000: 48).

Before the death of a person, his/her soul makes the final journey around this sacred territory. The soul successively visits guardian spirits, who determine the destiny of the person, and the soul asks protection from each of them. In this matter, the spirits obey the decision of the life-giving goddess Kaltas , and can extend the life of the person for several days (from three to seven). If the measured term of a person’s life has not run out, each of the spirits may keep the soul back for some time. In this journey, the soul first goes to the south to Kaltysyanskiye Yurty, the place where Kaltas lives, and asks the supreme goddess whether its days are over. If this is the case, Kaltas allows the soul to move even further to the south, to Mir-susne-khum / As-tyi-iki in Belogorye. If he also allows the soul to move further, the soul, screaming and crying, turns to the north and goes on to Vezhakary to Yalpus-oyka / Em-vozh-iki . His decision is particularly important, since the last location, the village of Vanzevat, the place where the ruler of the Lower World Khin-iki, “The Ruler of diseases” resides, is still ahead. Two guardian spirits, brothers, live near Vanzevat and Malyi Vanzevat. If they let the soul go further, it leaves for good for the north, to the land of death, located near the mouth of the Ob River (Schmidt, 1989a: 223). In the journey of the soul before its death to the main mythical guardian spirits, the center of worship of “the Old Man of the Sacred Town” is the last stop before the soul’s departure to the Ruler of disease (Schmidt, 1989b: 15).

A slightly different version of the belief associated with the last journey of the soul was recorded by V.M. Kulemzin from the Northern Khanty. Two days before death, ven-is , “the great soul”, leaves a person and goes to the life-giving goddess Kaltas to ask her permission to live for some more time. The goddess does not allow that, since she determines the hour of death. Then the ven-is goes to Urt *, who allows the soul to live two more days. Further, the soul goes to the Vezhakary old man, and he gives the soul permission to live for three more days (Ocherki…, 1994: 363).

It seems that the worship of a bear-like deity has existed in this territory at least since the Early Iron Age and continues to the present day; the distinctive feature of the iconography of the deity is its depiction in full height.

The bear-deity and its representations according to archaeological data

Until recently, only sporadic representations of bears standing in full height have been known from bronze casting and engravings on metal (bronze and silver) objects of the Early Iron Age. Thus, cast images of the bear have been described as a part of the Ust-Poluy culture (Chernetsov, 1953: 137, pl. VI, 6; Ust-Poluy, 2003: cat. 34).

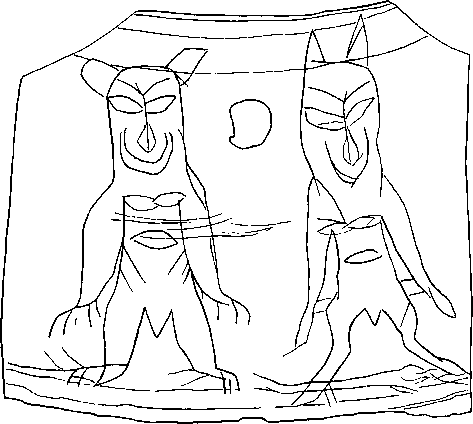

Two bronze mirrors of the so-called Sarmatian circle from the collection of the Museum of Nature and Man (Khanty-Mansiysk) show representations of the bear: a standing bear in full height is depicted in the center of one mirror (Chernetsov, 1953: 155, pl. XIII, 3; Pristupa, Starodumov, Yakovlev, 2002: 46), and two anthropozoomorphic deities with the emphasized figure of the standing bear appear on the other mirror (Chernetsov, 1953: 155, pl. XIII, 2; Pristupa, Starodumov, Yakovlev, 2002: 55). Such mirrors were common in the Lower Ob region in the 2nd century BC –2nd century AD (Pristupa, Starodumov, Yakovlev, 2002: 17). There is also a bronze pendant with two carved zoomorphic figures (a bear and wolf) from the assemblage of the Early Iron Age in the village of Khurumpaul in Beryozovsky District of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra (Baulo, 2011: Cat. 374) (Fig. 1).

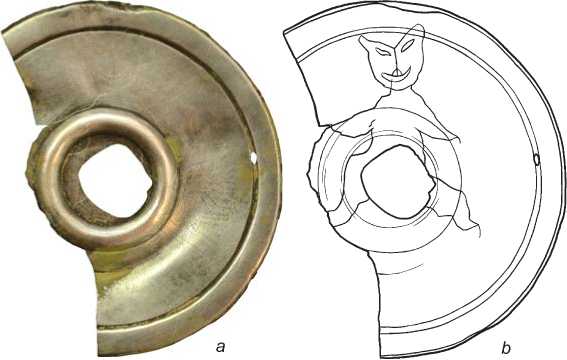

A silver “saucer” (8.5 × 8.0 cm in size), which is the convex bottom of a bowl which has not survived, was found during unauthorized excavations on the cape in the Muratka River basin (the right tributary of the Ob, Oktyabrsky District of Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra), together with ten small bronze anthropomorphic figurines of the Ust-Poluy culture. The

Fig. 1. Bronze pendant with the figures of a bear and wolf.

central gilded roundel is decorated with a sophisticated six-petalled rosette (Fig. 2, a ). Such rosettes were typical of the silver vessels of Sogdia and the adjacent regions; the closest parallel is the roundel on a thin-walled bowl of the 6th century from Chilek (Samarkand Museum) (Marshak, 1971: Fig. 13, pl. 1).

A hole was punched in the edge of the “saucer”, and a large figure of a standing bear with his legs spread wide was engraved under the hole. The image shows claws, ribs, male sexual characteristic, and three faces on its head. Five fish and a bird are depicted around the bear (Fig. 2, b ). Three large figures of beavers and two small figures resembling dogs were engraved on the reverse side of the “saucer”. Judging by the hole which was punched in the edge in such a way that the bear figure was located vertically when the “saucer” was hung, most likely the “saucer” was a kind of “icon” with the representation of the taiga deity. Taking into account the dating of the Chilek bowl with a similar pattern in the roundel, the time needed for the second bowl to reach the Ob region, and the period of its functioning until the fragmentation, it can be assumed that the figure of the sacred animal could have been hardly engraved on it before the 7th–8th centuries.

New materials on the subject of this article appeared in the summer of 2014, when as a result of an amateur search using metal detectors, unidentified persons discovered two hoards located near each other. The exact place of the discovery is unknown; it is tentatively placed on one of two small islands near the mouth of the Kazym River (Beloyarsky District of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra). The total number of discovered bronze objects is close to 300: these are mirror-rattles, mirrors of the Sarmatian circle, cast

Fig. 2. Silver “saucer” with engraved animal representations. a – photograph of the front side; b – drawing of the representations on the front side.

objects (buckles, pendants, and animal figurines)*. Many mirrors are engraved (approximately 60 spec.); in some cases, the motifs of their engravings coincide with those of the mirrors from the collection of the Museum of Nature and Man (MPiCh). It had been previously believed that the collection was confiscated in the 1930s from the Khanty and Mansi by the officers of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) in the basin of the Northern Sosva, Lyapin, or Kazym rivers (Pristupa, Starodumov, Yakovlev, 2002: 12). Taking into consideration hoards with similar mirrors, found near the mouth of the Kazym River, we can assume that both collections (from the 1930s and from 2014) belong to the same group of artifacts which found their way to the north of Western Siberia probably in the first centuries AD and became a part of the ritual paraphernalia of the local population.

The Kazym hoard included five objects with representations of the standing bear: bronze mirrors and a small silver plate. It should be clarified that the mirrors were identified as imported objects, presumably from the south of Siberia, while the “bear” engravings were already made in the north of Western Siberia, possibly not later than the middle of the 1st millennium AD. It is crucial that these artifacts were found near the main sanctuary of Yalpus-oyka / Em-vozh-iki (“The Old Man of the Sacred Town”), which is located on a high right bank of the Ob

River opposite the village of Vezhakary, at a well-known archaeological site.

Bronze cast mirror with engraving (Fig. 3, a , b ), 11.5 cm in diameter. Two holes were drilled in the edge of the object opposite to each other. The following representations were engraved on a wide band running around a cone-shaped protrusion and raised fillet (clockwise): a bird with a long tail (peacock?), horse with saddle, horse, horse’s head, horse, animal with big horns, head and a part of the torso of a horned animal, a horse with a saddlecloth and fluffy tail, horse with saddle, animal with big horns, and horse with a fluffy tail. Some of the animals are shown walking around the circle one after the other, and a part of them are shown coming from the opposite direction. This object is likely to have belonged to the group of the so-called mirrorrattles, which appeared among the nomads in the late 6th–5th centuries BC; their Eastern origin is undoubted (see review in (Shulga, 1999)).

In our case, it is important that a large figure of a standing bear was engraved with a sharp cutting instrument on top of the mirror decoration (see Fig. 3, c ): the paws are spread wide to the sides, and the male sexual characteristic is indicated. The figure of the animal is placed vertically exactly under the drilled hole. This supports the assumption that the hole and the engraving were made at the same time. The mirror might have been hung on a string or attached to a metal rod.

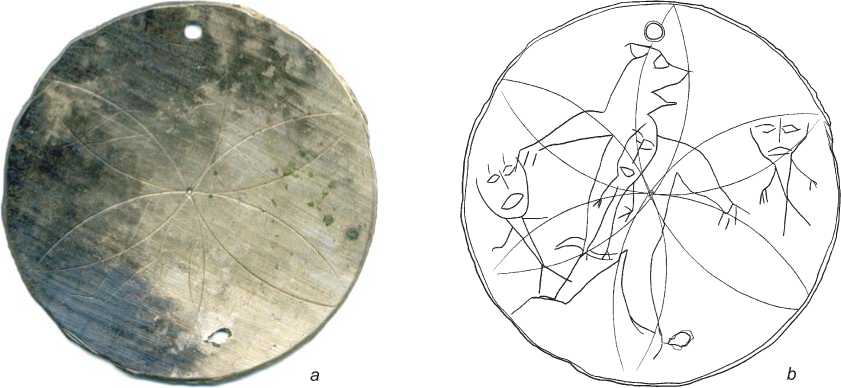

Fragment of cast mirror of white bronze (Fig. 4, a ). Its dimensions are 8.3 × 6.0 cm. Initially the object was of round shape with a high fillet in the center of the reverse side. A hole was punched in the edge. A part of the mirror and its center were broken away and have

Fig. 3. “Eastern” bronze mirror from the Kazym hoard.

a – photograph of the front side; b – drawing of the front side; c – drawing of the engraved figure of the standing bear.

not survived. The front side* is smooth. A figure of the standing bear with his paws spread wide is engraved on the reverse side (Fig. 4, b ).

Fig. 4. Fragment of a mirror of white bronze from the Kazym hoard. a – photograph of the reverse side; b – drawing of the engraved figure of a standing bear.

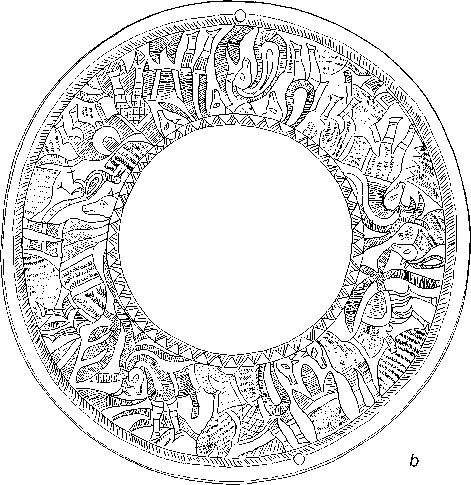

Bronze wrought mirror with engraving . It is 6.9 cm in diameter. Two holes were drilled in the edges. The front side is smooth; it shows the engraving of three anthropomorphic figures in frontal view; a beaver moving to the right is depicted underneath. The reverse side was originally decorated with a carved six-petalled rosette (Fig. 5, a ). Three anthropomorphic figures were engraved with thin lines on top of the rosette, and a standing bear with his paws spread and his head turned to the right was depicted with deep lines on top of the central figure (Fig. 5, b ).

Pendant of oval shape (Fig. 6). Silver, hammer-work, engraving. Its dimensions are 3.0 × 2.5 cm. A hole was drilled in the edge for attaching or suspending. Almost

Fig. 5. Bronze mirror of the Sarmatian circle from the Kazym hoard.

a – photograph of the reverse side; b – drawing of the engraved representations on the reverse side.

the entire surface of the plate is covered with the figure of a standing (sitting?) bear with raised left paw; the male sexual characteristic is shown.

Meaning of the composition on the mirror from the Kazym hoard according to ethnographic data

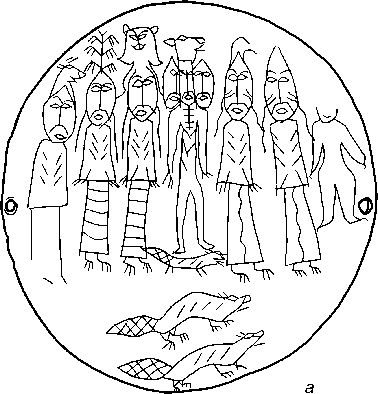

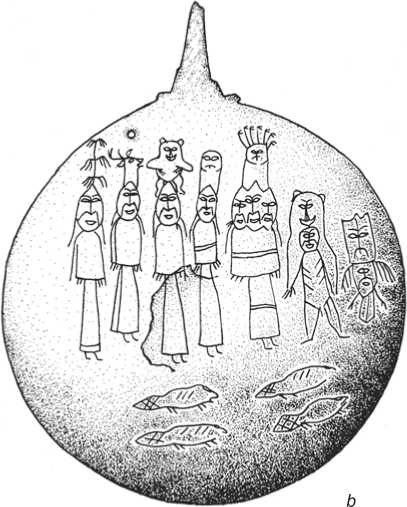

A wrought bronze mirror 5 cm in diameter is decorated with 12 circles on its reverse side. A recess for a compass leg is in the center; two holes are made in the edge. The front side is smooth; a sophisticated composition was drawn on it with a thin cutting tool already in Northern Siberia (Fig. 7, a ). Five anthropomorphic figures are represented wearing hats with a variety of tops (from left to right): in the form of animal heads, an umbelliferous plant, and a bear; a sixth figure does not have a top to its hat; the seventh figure is likely to be a standing bear, which can be identified not only by the poorly preserved silhouette (the mirror has been burned), but also by a mirror with a similar composition from the collection of the MPiCh (Fig. 7, b ) (Chernetsov, 1953: 155, pl. XIII, 2; Pristupa, Starodumov, Yakovlev, 2002: 55). In the lower part of the mirror, the figures of three beavers were engraved. Their distinguishing feature in the art of the Early Iron Age in Western Siberia is a tail cross-hatched with diamond shapes.

The meaning of such compositions with anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representations has been analyzed many times. According to V.N. Chernetsov, the composition “is well explained by certain rituals, known from the ethnography of the Ob Ugrians, which are dedicated to the ancestors of the family clan and

Fig. 6 . Silver plate with the engraved figure of a standing bear from the Kazym hoard.

particularly to phratry ancestors; specifically, rituals associated with the winter solstice and spring equinox, which took place in the sanctuary of the Por phratry” (Chernetsov, 1953: 138)*.

We should recall that the sanctuary of the Por phratry is the sacred place of Yalpus-oyka / Em-vozh-iki opposite the village of Vezhakary. Well-known bear festivals which were the most explicit demonstration of the cult of the bear-deity, were celebrated precisely in this area,

Fig. 7. Drawings of anthropozoomorphic figures on the mirrors of the Sarmatian circle.

a – from the Kazym hoard; b – from the collection of the MPiCh (after (Pristupa, Starodumov, Yakovlev, 2002: 55)).

often jointly by the Khanty and Mansi. According to the materials of Chernetsov, in the early 20th century bear festivals in Vezhakary were constantly attended by the Sosva Voguls who would come across the Ob River for hunting (Istochniki…, 1987: 214). Both Khanty and Mansi deities were represented at the “dances of the spirits” in the Ob villages. As an example we can mention the festival in Ilpi-Paul (Yurty Novinskiye) in January of 1937. The deities from Northern Sosva ( Yipyg-oyka , “Eagle-owl-old man” from Khalpaul; Nyaksimvol otyr pyg , “The son of the mighty warrior from Nyaksimvol”; Vissum sunta otyr pyg , “The son of the mighty warrior from the village at the mouth of the Visim”; Khalev-oyka , “Seagull-old man from Aneyevo”), the Lozva ( Yovtim sos otyr , “Mighty warrior from the stream of Yovtim”), the Lyapin ( Vorsik-oyka , “Wagtail-old man” from Maniya Paul), the Kazym ( Kasum nai ekva , “The Kazym fiery woman”), and the Ob (the patrons of Aleshkinskiye Yurty, the villages of Sherkaly and Lokhtyt-kurt) would “come” to welcome the bear (Ibid.: 216–218, 246). The tradition of inviting guardian spirits to bear festivals continues until today. Thus, the second part of the Yuilsk bear games is dedicated to the guardian spirits of individual family clans, the masters of rivers, lakes, woods, etc.; songs are sung in name of the coming deity (Moldanov, 1999: 24–30, 36, 41); the spirit Voshchan iki comes with an “iron staff” (from a very tall larch tree) (Ibid.: 25); Kat veshpi yapal , “A creature with two faces” also comes to the games (Ibid.: 57). The dances at the bear festival of the Mansi (seven circles) are also performed by Yalpus-oyka himself, the son of Numi-Torum (bear) (Soldatova, 2007: 52).

As far as the images on the mirrors from the MPiCh collection are concerned (Fig. 7, b ), Chernetsov believed that the anthropomorphic figures were endowed with zoomorphic and other kinds of tops. According to him, the first figure on the left was the woman-plant Poryg followed by a woman-roedeer, woman-bear and womanowl, a three-headed creature, bear with its face on its chest, and eagle-owl. The scholar also believed that these creatures represented anthropozoomorphic ancestors of the genealogical groups of the Ob-Ugrians, and the whole composition reflected the dances which the ancestors performed during periodic and sporadic festivities (Chernetsov, 1971: 91–92).

The figures on the mirror from the Kazym hoard (Fig. 7, a) find their definite parallels in the pantheon of the Ob Ugrians: zoomorphic images of guardian spirits are emphasized by the tops of their hats (masks?). A deity in the form of an elk was revered by the Mansi Sambindalovs and Elesins in the upper reaches of the Lozva and the Northern Sosva rivers (Chernetsov 1939: 25–26; Chernetsov, 1947: 172; Istochniki…, 1987: 200–202); in the Mansi folklore, the umbelliferous plant (on the head of the second figure from the left) was associated with the ancestors of the Mansi Por phratry (Chernetsov 1939: 22); three-headed forest menkv spirits (fourth figure from the left) were revered by the Mansi from the Northern Sosva (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 148, 156–157, 218; Gemuev, Baulo, 1999: 100). The rightmost figure may represent a bear-deity, and the image of the bear on the top of the hat of the third figure from the left may represent the son of Yalpus-oyka—this deity was also known among the Mansi. The diaries of Chernetsov have a record that in the 1930s the guardian spirit of the family of Pakins, Yalpus-oyka-pyg (“The son of Yalpus-oyka”), was located in the village of Nirus-Paul (the basin of the Tapsuy River). In certain years, the figure of this guardian spirit would be brought to Vezhakary for “visiting” his father Yalpus-oyka (Istochniki…, 1987: 151).

Thus, we can assume that the deities which participated in the ancient mysteries taking place on the right bank of the Ob River, were engraved on bronze mirrors. Their zoomorphic hypostasis was emphasized by the decor of their hats; the figures included a bear-deity and possibly his son. The preservation of the traditions of representing the guardian spirits at the bear festival in the villages of the Ob Ugrians located on the right bank of the Ob, is an eloquent testimony of the stable centuries-old mythological beliefs and rituals, common for the region and the local population.

Certainly, the standing bear in full height is not the only, but a relatively rare (and as I have tried to show, geographically confined) variant of bear representations. Cast bears in the so-called sacrificial*, sacred, ritual posture with the head shown between the front paws of the animal in top view** are much more commonly found among the archaeological artifacts of the Early Iron Age and the Middle Ages. Hollow bear figurines are also widely known.

Bronze castings with the motif of a “bear’s head between its paws” in the Kazym hoard amount to 10 objects (three epaulette-shaped objects; others have round and rectangular shapes), which means that the objects with this version of bear representation are rare among the artifacts (about 400 spec.) and they might have been imported together along with the main bulk of the objects. Another point is of no less importance: the Sarmatian mirrors were imported goods in the north of Western Siberia; the local people depicted the standing bear on them, but there are no known engravings of the type with the “bear’s head between its paws”. They are also unknown from other regions of Western Siberia. This may indicate that cast objects with the representations of the bear in the sacred posture in the Kazym hoard also belong to imported objects. Moreover, bears were most likely not hunted in the Early Iron Age on the right bank of the Ob River, in the “primary territory of bear worship” (according to E. Schmidt), which also was formerly suggested by Chernetsov (1939: 29; 2001: 35).

Thus, it can be assumed that the objects with the “bear’s head between its paws” motif were not a part of the bear cult; they must have been a kind of distinctive token for hunters on the occasion of a successful bear hunt. The number of animal’s heads in bronze castings (buckles, bracelets, finger guards) might correspond to the number of hunted bears: buckles with one to six heads (see, e.g., (Chemyakin, 2003, 2006; Baulo, 2011: Cat. 319–326)) and even with thirteen heads are known; eight killed animals, for example, could have been be marked by two buckles with four heads each, etc.

As far as bronze hollow bear figurines are concerned, it seems they were associated with prey-animals by hanging such objects on the belts of the hunters or other clothing with magical purposes for ensuring successful hunting. It seems that the engraved figures of bears which were depicted in side view, in motion, were regarded as prey-animals.

The iconography of the bear-deity according to ethnographic evidence

Representations of the bear among the Ob Ugrians are known from the early 20th century. In the earlier periods, the ethnographers who worked in the north of Western Siberia did not have sufficient drawing skills; photographs of the objects also started to be taken relatively recently.

Most of the paraphernalia with bear symbolism is related to the well-known bear festival, which often took place on the occasion of procuring the animal in the hunt (see, e.g., (Sokolova, 2009: 537–569)), but it could also be celebrated in honor of bear-skins which already were in possession. During the ritual, the bearskin would be brought into the house, rolled up, and laid on the table in the honorary corner in such a way that the bear’s head would rest between its front paws. In spite of a sufficiently wide occurrence of this ritual among the local groups of the Ob Ugrians, the sacred posture of the bear’s “head between its paws” has not became a part of their ornamental decoration.

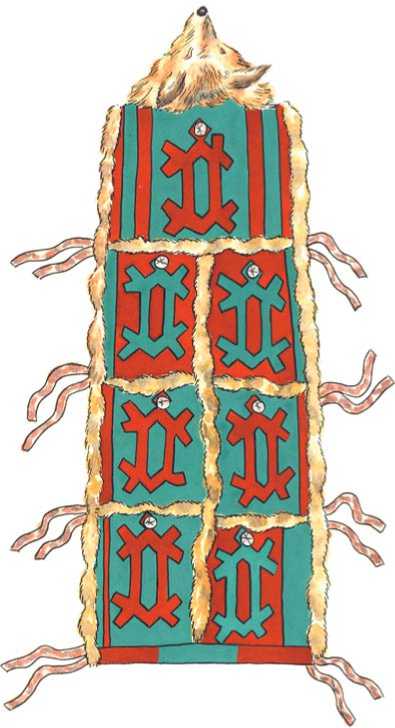

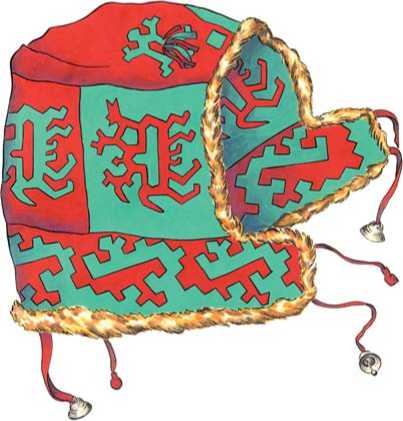

On the sacred paraphernalia of the Mansi and Khanty of the late 19th–early 20th centuries, the bear is shown standing in full height: among the Northern Mansi—in the sacred ornamental patterns (they were brought to Finnish museums after the expedition of A. Kannisto in the early 20th century) (Vahter, 1953: Pl. 189, 1 , 2 ); and among the Kazym Khanty—on birch-bark objects (Shukhov, 1916: Pl. II, 5, III, 3), bone finger guards (Ibid.: Pl. III, 2; Rudenko, 1929: 33), mittens of the participants of the bear festival (Shukhov, 1916: Pl. III, 1; Rudenko, 1929: Pl. XV, 3), and sacrificial veils (Gemuev, Baulo, 2001: Cat. 114, 115, 119). In these cases, the Ob Ugrians perceived such a pattern as a figure of the bear-deity, while in representations associated with everyday life, the bear was shown in side view as a prey (Rudenko, 1929: 22–23).

Fig. 8. Warrior belt with the representation of two standing bears in the center. The Synya Khanty, mid-20th century.

Fig. 9. Ritual quiver with the figures of a standing bear. The Beryozovo Khanty, mid-20th century.

Fig. 10. Mittens for the bear festival with the figures of standing bear. The Beryozovo Khanty, 1960s–1970s.

The tradition of portraying the standing bear-like deity survived until the mid-20th century and has not changed until today. The examples are the warrior belt of the Synya Khanty (Fig. 8), a ritual quiver (Fig. 9) and the mittens (Fig. 10) of the Beryozovo Khanty, and the warrior helmet of the Sosva Mansi (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Warrior helmet with the figure of a standing bear on top. The Mansi of the Northern Sosva, 1960s–1970s.

The studies today increasingly focus on the surviving paraphernalia rather than on fragmentary information: even at the end of the 19th century N.L. Gondatti, who collected information about the bear festival, expressed regret that “everything is forgotten by the Ostyaks, the dwellers at the main flow of the Ob” (1888: 65). Nevertheless, the Ob Ugrians of today still maintain the difference between the meaning of bear-deity and bear-prey. According to one version of the legend, at the bear festival, the bear-deity is represented by the son of “ Numi-Torum , the spirit of the Upper World” (Chernetsov, 2001: 7). Moreover, despite its “high” position, Numi-Torum himself is a bear (Chernetsov, 1939: 32), that is, a direct kinship between the bear-deity and the bear-like supreme god is demonstrated.

“The Old Man of the Sacred Town” acts as a mediator between the Middle and the Lower worlds (Schmidt, 1989b: 12). His function of the first bear-hunter and the founder of the bear rituals clearly emerges in the mythology of the Khanty and Mansi (Ibid.: 15).

Conclusions

Thus, the submitted archaeological and ethnographic materials make it possible to formulate the hypothesis that the cult of the bear-deity has been functioning among the local population of the Lower Ob region from at least the Early Iron Age until today. The followers of the cult distinguished between the iconography of the bear-deity and bear-prey: the former was depicted standing in full height, while the latter was represented in a specific sacred posture with its “head between its paws” in top view or in the form of a walking bear depicted in side view. Such a distinction was manifested in a particularly explicit manner in the Early Iron Age on the right bank of the Ob River, from its confluence with the Irtysh in the south to the village of Vanzevat in the Beloyarsky District of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra in the north; Schmidt identified this territory as the primary area for the spread of the cult of “the Old Man of the Sacred Town” (1989b: 11, fig. 3). The opinion of Chernetsov is especially important in this respect; according to him, “obviously, the bear was formerly not hunted at all” (1939: 29) and “periodic festivities in the sanctuary of the Por phratry at the time were the only rituals of the bear cult, while sporadic festivities observed today after hunting a bear, did not previously exist, because bears were not killed at all” (2001: 35).

In the 19th and 20th centuries, bear festivals were recorded among a number of local groups of Ob Ugrians, specifically on the territory Eva Schmidt identified as the primary and the secondary area of the bear cult. These rites played a key role in the center of the Por phratry— the village of Vezhakary of the Beloyarsky District, the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra. During the ritual, the hunted bear was placed in the “ancient” sacred posture with its “head between its paws,” but this posture did not become a part of the sacred ornamental decoration of the Mansi and Khanty. On various ritual paraphernalia, “The Old Man of the Sacred Town” continues to be depicted in a standing position.