The Origin of the Russkoust'intsy Ethnic Group and Exploration Work in the Indigirka River Delta

Автор: Strogova E.A.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Reviews and reports

Статья в выпуске: 51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The origin of the group of Russian Arctic old-timers living in the lower reaches of the Indigirka River in the village of Russkoe Ustye is still a subject of discussions. Despite the official version, the version about their origin from the Novgorod boyars, who allegedly settled in those places already in the 16th century, is being actively promoted. Written sources deny rather than confirm the legend with a complete lack of information. The article substantiates an attempt to verify the legend by means of ethnoarchaeological complexes, for which purpose archaeological prospecting works were carried out in the Indigirka delta in order to find predecessors of the contemporary village Russkoe Ustye and to assess their relevance for research. As a result, it became clear that the Staroe Russkoe Ustye tract could become the main source of archaeological material. Dating can also be attempted on the basis of materials from burials located in the Gulyanka area.

Archeology, Russians, Arctic, exploration, historical tradition, question of origin

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148329307

IDR: 148329307 | УДК: [39+902](571.56)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2023.51.295

Текст научной статьи The Origin of the Russkoust'intsy Ethnic Group and Exploration Work in the Indigirka River Delta

REVIEWS AND REPORTS

Ekaterina A. Strogova. The Origin of the Russkoust'intsy Ethnic Group … of the Russkoust'intsy, the answer to which is found in the historical legend about the fugitive Novgorod boyars who reached the mouth of the Indigirka River already in the 16th century.

This legend, stated in a more or less clear form in the book by A.G. Chikachev [3, p. 6], says that the ancestors of the Russkoust'intsy appeared in the lower reaches of the Indigirka as early as the 16th century as fugitives from Velikiy Novgorod. One of the tragic pages of Russian history of this century was the pogrom committed by the oprichniks of Ivan the Terrible in Velikiy Novgorod in 1570. The Novgorod Republic was a source of problems and an existential threat for the Grand Dukes and then for the Moscow Tsar for centuries. The united army of Mstislav Andreevich of Suzdal went to Novgorod, Ivan the Terrible’s grandfather Ivan III came there, putting an end to veche democracy, the Novgorodians themselves ruined Velikiy Ustyug and the Ustyug district several times. The Moscow authorities constantly felt the need to break the spirit of Velikiy Novgorod. Even the trip to the city itself was marked by more than one and a half thousand dead innocent people, as if they were walking through a foreign country. Historians are still arguing about the number of victims of the pogrom: some, relying on the Synodik of Ivan the Terrible, speak of one and a half thousand (which is already a lot for the 16th century), others indicate an incredible figure of forty thousand people, possibly including those who died from a terrible crop failure and the famine and plague epidemic that followed it. In such circumstances, more or less distant migrations of the population are inevitable.

It should be noted that there is also an “official” version of the origin of the Russkoust'intsy from industrial and service people who settled in the lower reaches of the Indigirka from the end of the 17th century. This version is well developed and based on written sources, but is almost always overshadowed by a vivid legend. Being a valuable historical source, legends still convey reality in a modified form and need to be studied and criticized. Unfortunately, the history of the origin of the Russkoust'intsy is still poorly understood, and the legend continues to be used without any scientific criticism. The relevance of such a study is not only in solving a local problem, but also in making a significant contribution to understanding the history of the Russian Arctic development as a whole.

From a scientific point of view, the beautiful legend has quite a few weaknesses. The first thing that comes to mind is the absence of any information about the existing Russian population, originating from the Indigirka discoverers. According to logic, for Ivan Rebrov “and his comrades”, a meeting with Russian people after long wanderings along “unknown rivers” among “unpeaceful foreigners” should have had the effect of an exploding bomb and should be reflected in their “tales”, “replies” and “questioning speeches”. Even with the loss of primary sources, the echoes of these testimonies would have turned into legends, and then would have entered the scientific and pseudo-scientific literature, as happened with the campaign of Panteley Pyanda. But, alas, despite more than two hundred years of studying events and publishing documents on the development of the northeast of Asia in the 17th century, not a single such evidence has been found to this day.

The petitions of Elisey Buza 1 and Ivan Erastov 2, the questioning speeches of Fyodor Chukichev 3 describe in detail the events of the time of the Indigirka discovery, but nothing is said about meetings with anyone except the indigenous population of these places.

Historical realities are not on the side of the legend either. The pogrom of Velikiy Novgorod was a one-time action, it was not followed by long-term repressions. Moreover, already at the end of 1572, Ivan the Terrible temporarily moved the Moscow treasury here and lived for some time himself. The famine and plague epidemic that followed the pogrom were certainly catastrophic for the devastated Novgorod land and caused mass migrations of the population, but there was no need to flee so far away.

It would seem that this is a ready criticism — the question can be closed, but, judging by the vitality and wide spread of the legend among those interested in the subject of Arctic navigation, more solid evidence is needed to confirm or refute it. The most effective way to solve this problem is a comprehensive study involving a wide range of historical, ethnographic and archaeological sources. The method of ethnographic-archaeological complexes, which has already shown its effectiveness in studies of the Russian population of Siberia, requires the coexistence of a group of modern population and archaeological sites associated with its formation. In order to identify sites associated with the formation of the Russkoust'intsy ethnographic group, in August 2016 and September 2022, reconnaissance surveys were undertaken in the delta of the Indigirka River.

The development of the Indigirka delta by Russian industrialists began a little later than its discovery, customs documents record the first runs to this “outside river” since 1642, by the middle of the century they become massive, and by the end of the century they became minimal due to the decline of fur extraction and redistribution of migration flows to the Far East. Map-scheme of the location of Russian settlements in the delta, compiled by local historian V.I. Shakhova [6], although not very accurate geographically, but demonstrates the development of the territory well. The Yakuts did not settle in the lower reaches of the Indigirka north of the Burulgin stone and the mouth of the Elon (Berelekh) river, since there is no food for cattle in the tundra. This is well illustrated by toponymy: all the names in the delta are absolutely Russian, and even those objects that received Yakut names at different times, retained Russian geographical reference — layda, kurya, viska.

Fig. 1. Zaimka Syrovatskoe on the Golyzhinskaya channel. Photo by E.A. Strogova.

Neighbors of the Russians in the lower reaches of the Indigirka were the Yukaghirs, who once settled in the delta itself, but Russians did not find them here already in the 17th century. Presumably, the ancient Yukaghir dwellings — chandals — were already abandoned and became the basis for legends. These dwellings were surveyed by S.A. Fedoseeva in 1959 as part of the work of the Yukagir expedition of the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences. During a visit to the Golyzhenskaya channel, 300 m from the coast, the remains of the Zaimka Syrovatskoe were discovered, which existed at the beginning of the 20th century, but was absent both in the Zenzinov’s list [7, pp. 130–133] and on the topographic map. The settlement was located in the middle of the tundra on a small low ridge. Six burials with wooden tombstones and crosses were found at the zaimka, and 100 m away from them — the remains of a dwelling, most probably, a balagan (Fig. 1).

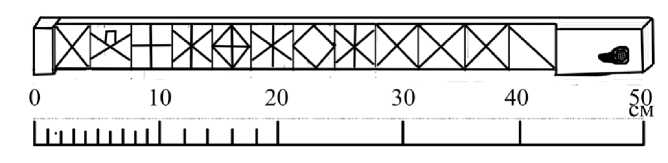

A special survey was carried out in the Stanchik site, located at the intersection of the Ko-lymskaya, Lundin and Keremsit channels; Zaimka Stanchik is apparently one of the oldest in the Indigirka delta, it is mentioned in the Zenzinov’s list [7, p. 131] as one of the landmark settlements. Convenient location at the intersection of the channels connecting the large branches of the delta with the ocean, allowed Stanchik to develop into a serious trading post by the end of the 19th century, where, according to the memoirs of the Russkoust'intsy, American trading schooners entered. Building of the church in the 18th century, which was studied and described in detail by A.V. Opolovnikov [8], indicates that already at that time there was a significant for these places settlement, and the name itself suggests the existence here in the 17th century of “district” winter camp of industrialists. The most interesting discovery was a wooden calendar fixed on the wall of the last house preserved on the surface (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Drawing figures on the calendar, Stanchik area.

The main purpose of the reconnaissance was the Old Russkoe Ustye tract, which is located on the left bank of the Russkoust'inskaya channel of the Indigirka river, 20 km upstream the modern Russkoe Ustye village (until 1988, the village of Polyarnyy) on the northern coast of a small peninsula formed by a meander of the Indigirka River. Until 1943, the ancient village of Russkoe Ustye was located here; the time of its foundation is unknown, but no later than the first quarter of the 18th century, since D. Laptev mentions the participation of the inhabitants of Russkoe Ustye in rescue his ship [9, pp. 233–234]. The territory of the settlement is a tundra area with small hills and ridges, where the remains of buildings are located [10, p. 232]. In addition, the territory is dissected by three small ravines, at the tops of which ice lenses are clearly seen — streams eroding the soil.

The remains of seven buildings and the cemetery are now clearly visible on the surface. Remains of two more buildings were found at the edge of the shore. One of the buildings was identified on the basis of a drawing found in the Archives of the YSC SB RAS in the materials of the ethnographer N.M. Alekseev, a member of the 1949 expedition 4. The drawing, judging by the inscription on it, depicts Russkoe Ustye in 1931 [10, p. 233]. The church building and the school are clearly visible here. The school was built in 1929 from the logs of the dismantled Ozhoginskaya church, carefully deconstructed when the settlement was moved to a new place, and nowadays, though in a poor condition, it is located on the territory of the modern settlement. The church, in the traditions of that time, was abandoned; it is likely that in the conditions of a shortage of wood, part of its logs was also eventually used for some kind of construction or for firewood. The image of the graves on both sides of the church helped to identify it, since now crosses are fixed on the ground on both sides of building No. 1.

A study of the bank edge along the entire length of the settlement showed that the cultural remains are concentrated in a layer of wood chips in gray silty loam, the thickness of which varies from 40 cm at the edge to 160 cm in the middle of the settlement. Under this layer, a small brown layer of humus is visible, which may be buried soil.

On the towpath formed after the water left, in a small area about 2 m long, 35 units of lifting material were collected, including 15 metal objects made of copper and iron, 8 bone products, 3 wooden objects, 3 stone weights, 4 fragments of porcelain .

Iron items are represented by fragments of two knives, a forked arrowhead, a massive forged iron ear of a cauldron, and two large forged nails 22 cm long [10, p. 234], a deformed iron ring made of a round wire with a diameter of 0.5 cm. The collection of iron products also includes scissors, which have an analogue in the materials of the Olenyokskiy winter hut [11].

The largest copper product is a deformed fragment of some kind of vessel (bucket, kettle, teapot?). The item was being repaired: a rectangular patch, attached with copper rivets, is clearly visible. Another such patch was found separately. The found earring is made of a tin-zinc alloy with a small copper content and covered with a thin layer of gilding [10, p. 233]. The lock shackle is made of the same alloy with a small addition of iron.

The most interesting piece of bone found at the site is a plate on the skid of the narta (subsledge) made of whale rib. Such plates were fixed in the front part of the skid after bending to improve sliding. That is why its front surface is polished to a shine. The Russkoust'intsy did not make such things themselves, but bought them from the Chukchi at the Anyuyskaya Fair.

Another interesting item is a miniature kopoushka (ear pick), made of mammoth bone and decorated with carving [10, p. 234]. The handle of the kopoushka is straight, fixed, rounded in cross section, smoothly connected to the plate and spoon. The handle and spoon are carefully pol- ished. The plate has a complex profiled shape and a complex openwork ornament. Its length from the extreme attachment point to the edge of the spoon is 6.3 cm (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Kopoushka from mammoth bone, Old Russkoe Ustye.

A saber-shaped beater for knocking snow off clothes, hats and shoes is made of a reindeer antler trunk, cut in half lengthwise. At the lower end of the beater, there are traces of a horn being cut and a round hole for attaching a cord 0.9 cm in diameter. Several items were identified by local residents as parts of dog harness, but no one could indicate the specific purpose and location of the parts. A small but heavy almost square-shaped weight measuring 5x6 cm was made of mammoth tusk.

In addition, three more wooden objects were found: a leaf-shaped wooden float with a straight base and three through holes. The large 1.6x2.0 cm hole is located in the center of the float, two other holes cut along the straight base, the float measures 10.0x7.4 cm and is 0.6 cm thick. Wooden detail interpreted as a spinner in the form of a round disk with a small hole in the center. In 2022, another unidentified object was added to the collection in the form of two halfmoon-shaped wooden handles connected by a half-meter rope, divided by knot marks into 8 almost equal parts, clearly intended for some kind of measurement.

Five small fragments of porcelain were also found, the age of which is not possible to determine due to the lack of hallmarks, and three stone weights-kibasa, attached to rings made of talnika twigs with bald rope. Such “kibasya”, as the Russkoust'intsy call them, are still used by fishermen.

The great thickness of the cultural layer, about 160 cm, suggests that cultural remains were deposited here for at least 200 years. A comparison of the modern outlines of the coast with a map reflecting the state of the area in 1972 showed a significant decrease in the territory of the Russkoe Ustye settlement — the location of an ancient village well known in ethnographic and folklore literature — as a result of destruction by the waters of Indigirka.

In the course of exploration work, it was impossible to miss the legendary Gulyanka — a tract located at the mouth of the Elon (Bereleh) River, which, in the minds of the Russkoust'intsy, is firmly connected with the history of their origin as the first settlement of their ancestors in these places. The settlement at the mouth of the Elon is mentioned in the diary of the astronomer E.F. Skvortsov (1908–1909) [12, p. 60], as non-existent by V.M. Zenzinov (1914) [7, p. 130].

A.G. Chikachev recorded the story of the Russkoust'intsy old-timer A.P. Chikacheva-Strizheva: “They came on kochas along the Golyzhenskaya channel and stopped at the mouth of Elon... and built 14 houses, a pub and a bathhouse. At first they drank and partied a lot. Several people drowned. That is why this place at the mouth of the Elon is still called “Gulyanka”. There was smallpox. Many people died. Afterwards, from Gulyanka, people moved to the place where now the Russkoe Ustye is” [3, p. 22]. It is interesting that our informant P.A. Cheremkin attributes the sad events at the Gulyanka to the beginning of the 20th century and does not connect them in any way with the formation of the Russkoe Ustye.

Fig. 4. Gulyanka tract, absence of a cultural layer in the coastal line, photo by E.A. Strogova, 2022.

The survey of the Gulyanka tract (Fig. 4) showed the complete absence of the cultural layer in the coastal line and any signs of structures (hills or depressions) on the surface. Only old graves indicate that once there was a settlement nearby, but its remains were completely washed away by the river waters.

The age of the graves cannot be determined by their appearance, as they look similar to the tombstones at the Old Russkoe Ustye. The features of the preservation of wooden objects and buildings in the Arctic do not allow visually determining the age of structures even approximately. In addition, drift-wood is used for construction, which can contain wood of any age. Special atten- tion was paid to the examination of structures of gravestones, because some local historians justify their antiquity by the presence of ship parts. Alas, the details of ancient ships were not found in the visible remains of the structures of gravestones. The age of the existing burials can be established only by their archaeological research.

Thus, the basis for applying the method of historical-archaeological complexes and obtaining new information about the past of the Russkoe Ustye has been obtained. The study of monuments of historical time by archaeological methods allows supplementing significantly the data of written sources, which, as a rule, do not preserve information about everyday life. Archaeological research of the Old Russkoe Ustye, and possibly the burials at Gulyanka, can play a significant role in the question of the origin and time of the beginning of the formation of the Russkoust'intsy as an ethnographic group. The materials obtained during archaeological excavations make it possible to trace in the dynamics the transformation of the culture of the Russkoust'intsy people in the process of its adaptation to the Arctic conditions and the degree of influence of a foreign ethnic environment.

Список литературы The Origin of the Russkoust'intsy Ethnic Group and Exploration Work in the Indigirka River Delta

- Azbelev S.N., Venediktov G.L., Gabyshev N.A. et al., eds. Fol'klor Russkogo Ust'ya [Folklore of the Russian Estuary]. Leningrad, Nauka Publ., 1986. 382 p. (In Russ)

- Druzhinina M.F. Slovar' russkikh starozhil'cheskikh govorov na territorii Yakutii, v 4-kh tomakh [Dic-tionary of Russian Old-Timer Dialects on the Territory of Yakutia, in 4 vol.]. Yakutsk, NEFU Publ., 2007. (In Russ)

- Chikachev A.G. Russkie na Indigirke [Russians on Indigirka]. Novosibirsk, Nauka publ., 1990. 189 p. (In Russ)

- Chikachev A.G. Russkie v Arktike: polyarnyy variant kul'tury: istoriko-etnograficheskie ocherki [Rus-sians in the Arctic: a Polar Version of Culture: Historical and Ethnographic Essays]. Novosibirsk, Nau-ka Publ., 2007. 303 p. (In Russ)

- Rasputin V.G. Russkoe Ust'e [The Russian Estuary]. Pisatel' i vremya: sbornik dokumental'noy prozy [A Writer and Time: A Collection of Documentary Prose]. Moscow, 1989, pp. 4–50. (In Russ)

- Shakhova V.I. Russkoust'inskaya natsional'naya kul'tura. Rabochaya tetrad' [Russian Ustyinsk Na-tional Culture. Workbook]. Yakutsk, Bichik Publ., 2011. 56 p. (In Russ)

- Zenzinov V.M. Starinnye lyudi u kholodnogo okeana. Russkoe Ust'e Yakutskoy oblasti Verkhoyan-skago okruga [Ancient People by the Cold Ocean. The Russian Mouth of the Yakutsk Region of the Verkhoyansk District]. Moscow, Kniga po trebovaniyu Publ., 2017. 134 p. (In Russ)

- Opolovnikov A.V. Sokrovishcha Russkogo Severa [Treasures of the Russian North]. Moscow, Stroyiz-dat Publ., 1989. 367 p. (In Russ)

- Ekspeditsiya Beringa. Sbornik dokumentov [Bering's Expedition. Collection of Documents]. Moscow, Glavnoe arkhivnoe upravlenie NKVD SSSR Publ., 1941. 418 p. (In Russ)

- Strogova E.A. Russkie v nizov'yakh Indigirki: pamyatniki starye i novye [Russians in the Lower In-digirka: Old and New Monuments]. Kul'tura russkikh v arkheologicheskikh issledovaniyakh: sbornik nauchnykh statey [Russian Culture in Archaeological Research: A Collection of Scientific Articles]. Omsk, Nauka Publ., 2017, pp. 232–237. (In Russ)

- Starkov V.F. Olenekskoe zimov'e [Olenek Wintering Place]. Russkie pervoprokhodtsy na Dal'nem Vostoke v XVII–XIX vv.: Istoriko-arkheologicheskie issledovaniya [Russian Pioneers in the Far East in the 17th–19th Centuries: Historical and Archaeological Research]. Vol. 5. Ch. 1. Vladivostok, Dal'nauka Publ., 2007, pp. 195–208. (In Russ)

- Boyakova S.I. Otechestvennye issledovateli XIX — nachala XX vv. o russkikh zhitelyakh nizov'ev In-digirki [Domestic Researchers of the 19th - early 20th Centuries about Russian Residents of the Lower Indigirka]. Russkie arkticheskie starozhily Yakutii: sbornik nauchnykh statey [Russian Arctic Old-Timers of Yakutia: Collection of Scientific Articles]. Yakutsk, Institute for Humanitarian Research and Problems of Indigenous Peoples of the North SB RAS Publ., 2019. 288 p. (In Russ). DOI: 10.25693/RusStarozil.2019