The Pazyryk style

Автор: Polosmak N.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146409

IDR: 145146409 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2021.49.4.043-056

Текст статьи The Pazyryk style

The question of whether there was a cultural affinity between the people of the Pazyryk culture and the contemporaneous population of the Xinjiang oases (the latter known from the materials of the burial grounds of Subashi, Shanpula, Yanghai, Jumbulak Kum, and a number of burial complexes that have been investigated in recent years in the Altai District of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region) is relevant and directly related to the identification of the southern border of the distribution area of this archaeological culture. Over the past decades, the distribution area of the Pazyryk sites has expanded thanks to the research carried out by Z. Samashev and H.-P. Francfort in Eastern Kazakhstan (Samashev, Francfort, 1999; Samashev et al., 2000) and V.I. Molodin, G. Parzinger, D. Tseveendorj in Mongolia

(Molodin, Parzinger, Tseveendorj, 2012). Samashev was right to correlate the Berel cemetery with the local group of Pazyryk people who roamed in this region and established a necropolis with burials of people of various statuses—from the highest-ranking in mound 1, middleranking nobles in mound 11, to commoners (2011: 206– 207). Research in the Mongolian Altai (northwest of Mongolia) has shown that quite few burial sites belonged to this community, whose main winter pastures and burial sites were located on the Ukok plateau (Molodin, Parzinger, Tseveendorj, 2012)* . It can be assumed that

the southern border of the Pazyryk culture’s distribution area runs along the Ukok highlands, although certain elements of this culture (often mistaken for the culture itself) are more widespread—for example, on the so-called Pazyryk monuments in Xinjiang. In recent years, owing to intense excavations by Chinese colleagues, information has appeared on the discovery and study of sites in the regions immediately adjacent to the Russian Altai—in particular, to the Ukok plateau, famous for the Pazyryk cemeteries (Polosmak, 1994, 2001). Many of the burial mounds containing remains of people and horses are unconditionally attributed by Chinese colleagues to the Pazyryk culture, probably because of the proximity of the distribution area of the latter (Mu, 2020). The paper entitled “Monuments of the Pazyryk culture in Xinjiang” presents a review of these sites, but the author is not so definite in assessing the cultural affiliation of the sites; he admits that the sites in question “may be attributed to the Pazyryk culture” (Ibid.: 138), and recognizes the differences between the sites he describes and the classic sites of the Pazyryk culture (Ibid.: 144). Russian researchers D.P. Shulga and P.I. Shulga (2017) are more accurate in their identification of Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai District of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. They considered the whole complex of features that would allow the attribution of the burials to the terminal stage of the Pazyryk culture. This approach led to the conclusion that the sites that have only one feature similar to the Pazyryk are in fact not Pazyryk. These researchers believe that such sites can be attributed to the Pazyryk culture only with certain reservations; they consider not only “classic” burials to be “Pazyryk” burials, but also all those ever recorded in the chains of the Pazyryk burial mounds in the Altai (their occurrences in these chains have not yet found an unambiguous explanation). These include the so-called Kara-Koba burials in stone boxes without horses; burials with western, southern, and southwestern orientation of the deceased; burials with horse bodies placed on the ceiling, rather than inside the burial chamber; burial mounds, in which there could be up to four deceased in one grave pit (such a feature has not been recorded in the Pazyryk graves); as well as burials of the so-called Korgantas type, with numerous skulls of domestic animals. Furthermore, it has been stated that some graves in Xinjiang contained sub-buried persons, which was atypical of the Pazyryk culture. D.P. Shulga and P.I. Shulga explain this deviation from the “Pazyryk standard” by local specifics; they argue that the rite itself is “intermediate in nature” (Ibid.: 25–27). The comparisons showed that the Xinjiang similar poor burials of the Chandmani culture, showing quite few features that find parallels in the Pazyryk culture and the Sagly culture of Tuva (Turbat et al., 2007).

burial complexes from the indicated region show more distinctions than similarities with the “classic” Pazyryk burials. Most likely, in Northern Xinjiang (on the border with Russia and Kazakhstan), there was a cultural formation (and probably more than one) that had nothing in common with the Pazyryk culture. In our opinion, identification of the Pazyryk sites should primarily take into account the “frozen” graves providing the most complete evidence of the culture, since if we judge only by the surviving things made of inorganic materials, then cultural parallels and cultural unity can be found in a far wider area* . From our point of view, the burial mounds discovered in Northern Xinjiang, in Dzungaria, between the Tian Shan and Altai, are not related to the Pazyryk culture in its classic (and most correct) understanding. According to the complex of features identified by D.P. Shulga and P.I. Shulga, these sites probably belong to another cultural formation, the main features of which have been described in sufficient detail (Shulga D.P., Shulga P.I., 2017: 25–27). The occurrence of such burials in the Pazyryk cemeteries can be associated with the penetration of the tribes from the eastern part of the southern face of the Altai Ridge into the Altai mountain pastures, and not vice versa. The Pazyryk people who wintered in Ukok most likely knew about the crossings through the Kanas and Betsu-Kanas passes, which one could use to get to the eastern part of the southern face of the Altai Ridge; but this does not mean that they used this opportunity. Whether this was necessary, is not yet obvious. In our opinion, a similar situation developed in antiquity in the regions adjacent to the Chikhachev Ridge, which separates the Altai Mountains and Tuva; nowadays, these areas are connected by an automobile road running through the Buguzun Pass at an altitude of 2068 m. On the Altai side of the ridge, the Pazyryk cemeteries of Uzuntal I, III, V, and VI in the vicinity to the village of Kokorya are known (Savinov, 1978, 1986, 1993; and others), while on the other side of the ridge no sites from this culture have been discovered. In 1994, the joint expedition headed by Vl.A. Semenov searched for the Pazyryk-type mounds in the Mongun-Taiginsky

District; but such sites were not found. The excavations of a large mound at the Kholash cemetery in 1995 did not give the desired result either. On the basis of the results of the expedition works, Semenov came to a fair conclusion that in the Scythian period this district was populated mainly by representatives of the so-called culture of inventory-less burials (Semenov, 1997: 7–9, 35). Being close in all respects to the Altai mountain valleys, this high-altitude territory, which today is a cattle-breeding zone, was not inhabited by the Pazyryk people; they did not nomadize there, they had no need to leave the Altai, which was and remains the “cattlebreeding paradise” (Radlov, 1989: 144–145)*.

The purpose of this paper is to show that separate elements of the Pazyryk culture in the burial rite and grave goods at the Northern Xinjiang sites cannot be considered as evidence of the spread of this culture in this region. The identification of mounds as Pazyryk burials on the basis of isolated similar elements alone tends to diffuse cultural identity: if we go in this direction, then we can expect that all sites that bear at least a remote resemblance to the original will be called Pazyryk. Chinese colleagues find “traces” of the Pazyryk culture also in territories located at a considerable distance from the Altai Mountains—in the Hami and Ili regions (Mu, 2020: 143). Traces there may be, but not the culture.

Cultural affinity or territorial proximity?

The diversity of the Pazyryk population was first established by methods of physical anthropology in the early 21st century (Barkova, Gokhman, 2001)**. Nowadays, this conclusion is confirmed by the data from paleogenetic analysis (Pilipenko, Molodin, Romanenko, 2012; Pilipenko, Trapezov, Polosmak, 2015). In this case, the anthropological and genetic features of the buried cannot be considered a solid ground for attributing particular burial complexes to the Pazyryk culture. Such criteria are still the commonality of the territory, funeral rites, material culture, and art objects.

A single territory (the Altai Mountains) and the lifestyle of cattle-breeders and hunters united various people; they developed their own unique style that characterizes the Pazyryk culture. The Pazyryk people maintained a certain style, which manifested itself in everything: from clothing to decoration of horse harness and dwellings*. An important part of their image was a tattoo; this indelible mark confirmed affiliation of these people to a particular society.

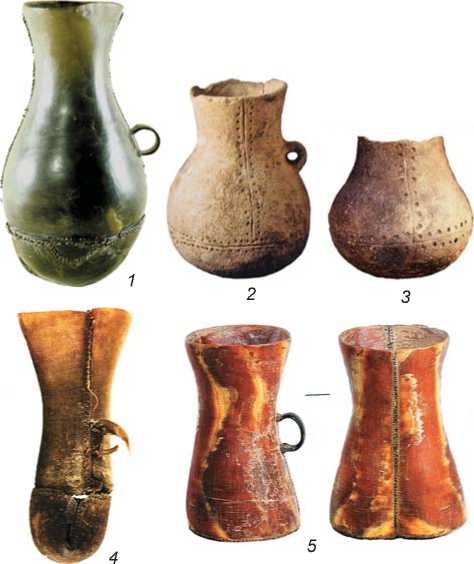

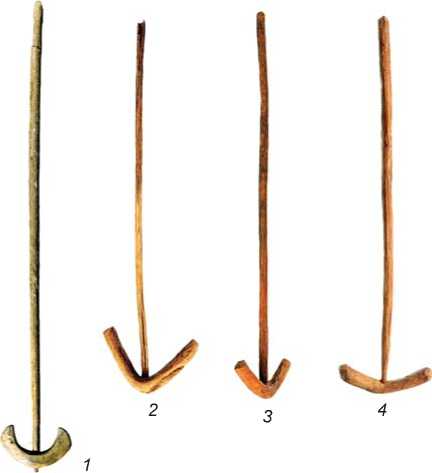

The discovery in the Xinjiang oases of burial complexes with goods made from organic materials allows us to see what the main external difference between the cultures was, and to understand what is denoted under the Pazyryk style. As it turned out, people living in different climatic zones, differing in lifestyle and subsistence strategies, had the same set of clothing items and largely similar household items. The closeness can be traced between wooden scoops, mugs, and tabledishes. However, similar wooden items existed also in other regions and cultures. Such items have been recorded in Early Scythian complexes; for example, in burial 5, mound Arzhan-2 in Tuva, a wooden scoop with the tip of the handle shaped like a horse’s hoof was found (Chugunov, Parzinger, Nagler, 2017: 406, pl. 68), as in the scoop from the 2nd Pazyryk mound, and in other similar items from ordinary mounds (Rudenko, 1953: Pl. XXI; Kubarev, 1987: 49). Similar items were also used in later periods: table-dishes and other wooden utensils were found in burials at the Kokel necropolis dating back to the period from the late 1st millennium BC to early 1st millennium AD (Veinstein, Dyakonova, 1966: 187, pl. X). Many goods in this category have survived till the ethnographic present, since they are universal forms convenient in everyday life. Among the utensils from the burials of Xinjiang, there are isolated items similar to the Pazyryk horn vessels (Fig. 1), and ceramic items similar in shape to the Pazyryk samples. In the graves of the Xinjiang dwellers, there occur the same stirring-sticks as in the female burial of mound 1 at the Ak-Alakha-3 cemetery, which may suggest that people of these regions drank the same milk (?) beverage (Fig. 2). wooden stiffening-frames on bow-cases, simple in their shape, are identical, which may indicate their similar structure and shape. Some Xinjiang samples bear carved ornaments that have nothing in common with the Pazyryk motifs (Fig. 3).

*We can speak about dwellings, since the burial chambers of the Pazyryk people imitated dwelling-houses, and sometimes they were real log cabins.

Fig. 1. Vessels from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1 , 4 ) and Xinjiang ( 2 , 3 , 5 ).

Horn vessels: 1 – mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-3; 4 – mound 1 at Verkh-Kaldzhin-2 (excavations by V.I. Molodin); 5 – burial 92 at Yanghai (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. III, p. 303, fig. 1]; ceramic vessels: 2 – Hongshawan, northern part of the Silk Road, Manas District of the Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture (The ancient culture…, 2008: 308, 1 ); 3 – burial at Jumbulak Kum (Debaine-Francfort, Francfort, 2001: 209, fig. 99).

Fig. 2. Wooden stirring-sticks from mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-3 in the Altai ( 1 ) and Yanghai in Xinjiang ( 2–4 ) (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. III, p. 172, fig. 1–3, fig. 5; p. 307).

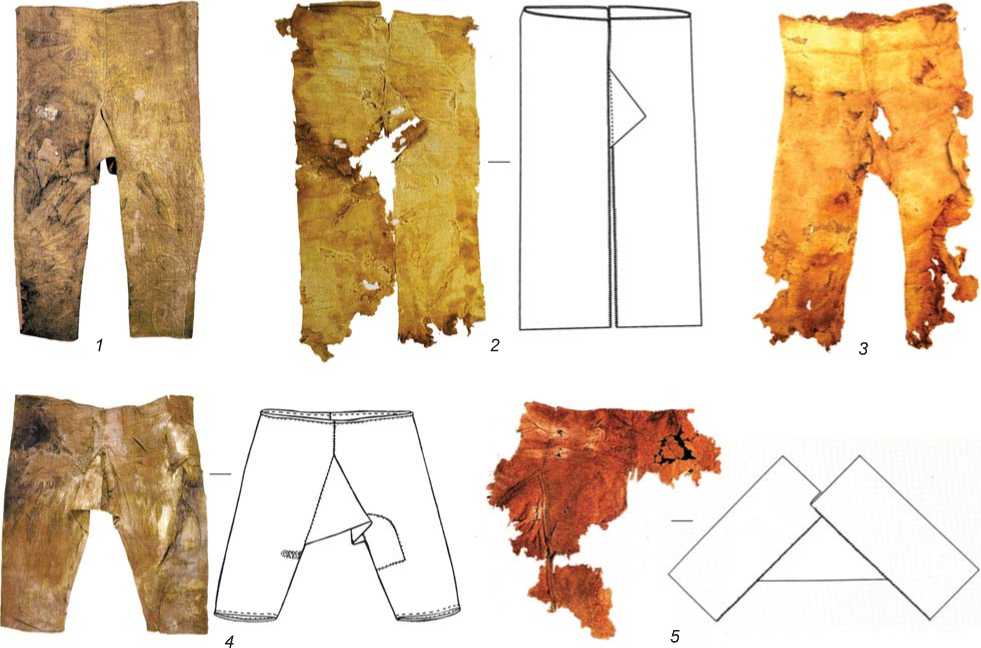

Sets of clothes of the residents of Xinjiang oases and the Pazyryk people* are similar in color (red, white, and black; more rarely blue and yellow) and in categories of clothes (fur coats, shirts, pants, and skirts). Women wore skirts made of narrow multi-colored stripes of woolen fabric sewn together horizontally (Fig. 4), long-sleeve shirts trimmed at the seams with red laces and braids (Fig. 5), and belts-cords woven from woolen threads. Some Xinjiang burials also yielded long felt and leather stockings similar to the Pazyryk ones (Fig. 6). Men wore similarly-cut woolen trousers: two legs joined by a rectangular piece of fabric. Of course, such apparel of a very simple cut could appear in various places independently (Fig. 7). This cannot be said of outerwear— fur coats. For the Pazyryk people, each fur coat was a unique product, a real work of tailor’s art, which showed a combination of various furs (from sheepskin to sable), dyed fur decorations, horsehair tassels, and leather appliqués. In addition, these fur coats were unusual in cut: at the back, they had a long separately sewn detail— a kind of a tail. For the inhabitants of the Xinjiang oases, outerwear was a very simple functional thing; it can be called a sheepskin coat (Fig. 8).

The above examples show that the funeral garments of human mummies from both regions are similar. Often, not only the style, cut, and color, but also the trimmings coincide. As is known from historical examples, such similarities were difficult to achieve even when these were urgently needed. For example, in the Middle Ages, when vassals who lived at a considerable distance from the castle of their lord needed to join his retinue in clothes of certain colors and styles, they received fabrics and instructions for sewing dresses in advance. Then it was possible to achieve a very approximate similarity; but even this was perceived by contemporaries as identity. The striking similarity between the clothes of the inhabitants of the Xinjiang oases and the Pazyryk people may be the result of contacts.

It would be difficult at first glance to find the distinctions between the population that left the Ak-

Fig. 3. Stiffening wooden frames on the bow-cases from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1 , 2 ) and Xinjiang ( 3–5 ). 1 – mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-1; 2 – mound 1 at Verkh-Kaldzhin-2 (excavations by V.I. Molodin); 3–5 – Yanghai burials (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. I, p. 169, fig. 1; vol. III, p. 293, fig. 4, 5).

Fig. 4. Skirts from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1 , 3 ) and Xinjiang burials ( 2 , 4 – 8 ).

1 – woolen skirt with a belt-cord and its pattern, mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-3; 2 , 6 , 7 – fragments of woolen skirts, Shanpula cemetery (Bunker, 2001: 25, pic. 15; fig. 63, 64, 93); 3 – fragment of a woolen skirt, the 2nd Pazyryk mound; 4 – reconstruction of a woolen skirt based on the remains from a burial at Jumbulak Kum (the Keriya River basin in the southern part of the ancient Silk Road (Desrosiers, 2001b: 193);

5 , 8 – fragments of woolen skirts from Yanghai cemetery (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. III, p. 269, fig. 4, 5).

Fig. 5. Shirts from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1 ) and Xinjiang ( 2–4 ).

1 – silk shirt and its cutting-pattern, mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-3; 2 – fragment of a shirt and its reconstruction, Yanghai (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. III, p. 276, fig. 2, 3); 3 – woolen shirt, Shanpula II (Bunker, 2001: 34, fig. 35); 4 – fragment of a woolen shirt and its reconstruction, burial at Jumbulak Kum (Desrosiers, 2001d: 196–197).

Fig. 6. Boots-stockings from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1 , 2 ) and Xinjiang burials ( 3 , 4 ).

1 – men’s felt stockings, mound 3 at Verkh-Kaldzhin-2 (excavations by V.I. Molodin); 2 – men’s felt stockings, mound Olon-Kuren-Gol-6; 3 – leather stockings, Yanghai (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. III, p. 220, fig. 6);

4 – a felt stocking, Jumbulak Kum (Desrosiers, Francfort, 2001: 164).

Fig. 7. Pants from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1 , 4 ) and Xinjiang ( 2 , 3 , 5 ).

1 – woolen pants, burial 1 at Ak-Alakha-1; 2 , 3 – pants and their cutting-pattern, Yanghai (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. II, p. 928; vol. III, p. 270, fig. 5; p. 272, fig. 2); 4 – woolen pants and their cutting-pattern, mound 1 at Verkh-Kaldzhin-2 (excavations by V.I. Molodin); 5 – fragment of woolen pants and their cutting-pattern, burial at Jumbulak Kum (Desrosiers, 2001c: 195).

Fig. 8. Men’s fur coats from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1 ) and Xinjiang ( 2–4 ).

1 – mound 3 at Verkh-Kaldzhin-2 (excavations by V.I. Molodin); 2 – burial at Wupu (Hami ancient civilization, 1997: 24, fig. 49).

Alakha kurgans and the inhabitants of the Xinjiang oases if the former did not have ornaments that, in our opinion, it would be more correct to call identification marks*.

It is clear that the similarity of the basic outfit is not yet a sign of affinity of cultures. Perhaps this is evidence of closeness, but territorial in this case. The uniform cut of top- and bottom-wear, headgear, and footwear is, as was observed in the process of studying the folk outfit of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, a region-specific feature, but not an ethnic differentiating feature, and does not even indicate common roots in the culture of the peoples of the region (Lobacheva, 1989: 35; 2001: 70–71, 92). Only details can serve as culturally differentiating indicators.

Fig. 9. Men’s headgear- and belt-decorations from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1–6 ) and Xinjiang ( 7–9 ).

1–4 , 6 – men’s headgear decorations, mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-1; 5 – wooden belt-plates, mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-1; 7 – bronze decoration of men’s headgear, burial at Jumbulak Kum (Francfort, Lacoudre, 2001: 205–206, fig. 92); 8 – headgear decoration, burial in Keriya oases (The ancient culture…, 2008: 33, fig. 5); 9 – men’s mummy wearing headgear, Keriya (Ibid.: 32, fig. 3).

Given the general similarity of the items of men’s and women’s clothing, the outfits of the inhabitants of the Xinjiang oases and the Pazyryk people (we can compare only these, since they are in approximately the same state of preservation; so, this is an equivalent comparison) show certain distinctions that are determined by ornaments. The men’s Pazyryk outfit was decorated with wooden figurines of horses with ibex horns and deer figurines on a headgear, a torque bearing images of predators, and belt-decorating plates with carved animal figures (Fig. 9). In an outfit of the Pazyryk women, ornaments were a figurine of a lying deer decorating a wig, the so-called aigrette, a metal hairpin with a deer-shaped pommel, carved plait decorations, images of birds, torques and diadems bearing images of animals (Fig. 10)—everything that is missing in the outfits of Xinjiang residents, including a wighairstyle.

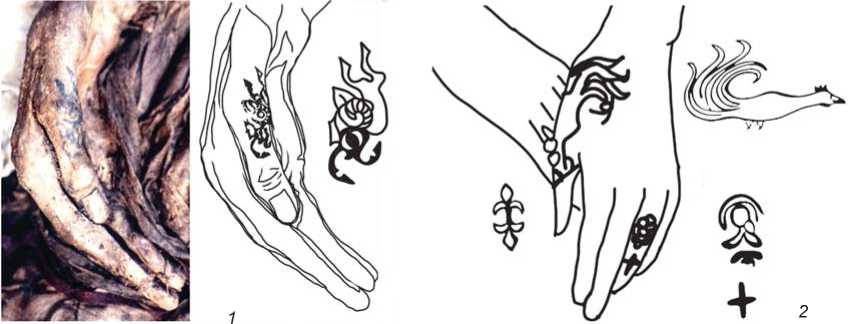

The Pazyryk style implies not only the style of personal ornaments, but also everything that surrounded people—decorations of household utensils, horse harness, coffins, felt items, and weapons. One of the main distinguishing features of the Pazyryk culture is a tattoo. Tattoos on bodies were the feature that united all Pazyryk people, their indelible marks indicating a relationship stronger than blood; these were the signs distinguishing between kin and strangers in this and the other world. Differences in the number of signs, location of images, and compositions emphasized the individuality of each person. The history of a person was “recorded” on his or her own body; but the images and signs, like the letters of one alphabet, were the same for everyone. Throughout a person’s life, other signs and images would be added to his or her body. Tattoos differed in details, depending on the sex, status, and age of people (Barkova, Pankova, 2005). The tattoos reproduced the same images of the animals, birds, fish, imaginary creatures, and signs that were carved from wood or made of felt and leather (Fig. 11). If the tattoo of a man from

Fig. 10. Women’s headgear and personal ornaments from the Pazyryk burial complexes in the Altai ( 1–3 , 5–9 ) and Xinjiang ( 4 ).

1–3 – felt caps, the 2nd Pazyryk mound ( 3 – reconstruction by D.V. Pozdnyakov); 4 – felt headgear on women’s mummy, Subashi (Desrosiers, 2001a: 155, fig. 12); 5–8 – wooden decorations, mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-3; 9 – headgear with decorations (reconstruction), mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-3.

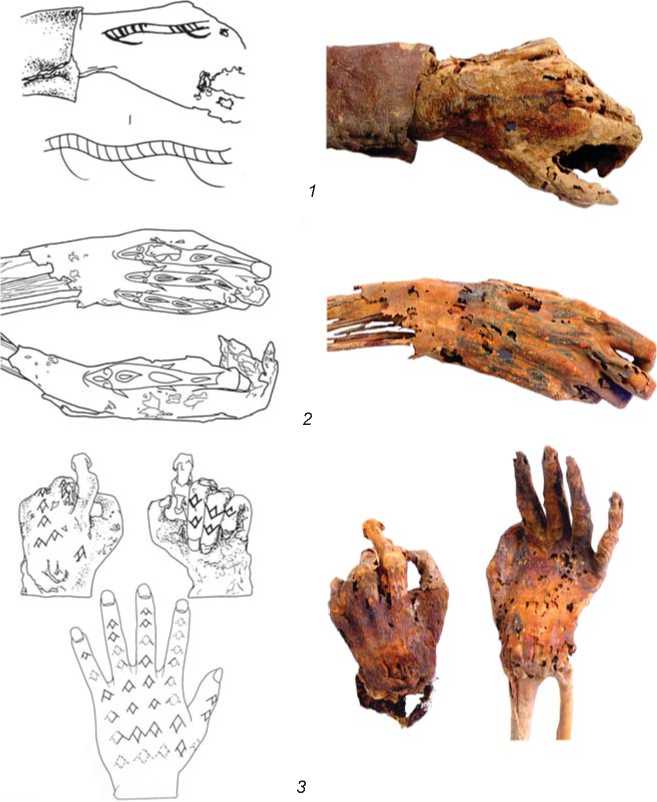

Fig. 11. Tattoos on the Pazyryk mummies of the Altai.

1 – on hands and fingers of a woman, mound 1 at Ak-Alakha-3; 2 – on fingers of a woman, the 5th Pazyryk mound.

Fig. 12. Tattoos on hands of the mummies of Xinjiang. Yanghai cemetery (Sintszyan…, 2019: Vol. I, fig. 1, 2 , 9 ; vol. III, p. 211, fig. 1, 5 ).

the 2nd Pazyryk mound is interpreted as “zodiacal” (Marsadolov, 2021), then the whole art of the Pazyryk culture should be considered in the same way; but is the author of this hypothesis ready to ascribe zodiacal meaning to the entire Pazyryk bestiary? Even though on the hand of a woman from the 5th Pazyryk mound a composition is depicted that we have not seen before, this is not the reason to consider the buried a representative of another culture (Azbelev, 2017). Today, we only have information about a small number of Pazyryk people with tattoos, although we know for sure that all representatives of this culture had tattoos. And, as all the previous experience has shown, conclusions based on small amount of data are premature.

Quite different signs are reproduced on the rear sides of the hands and fingers of the inhabitants of the Xinjiang oases. In execution and composition, these images are absolutely dissimilar to those found among the Pazyryk people. It has already been noted that on the bodies of the Pazyryk people, tattoo-images of animals, birds, and fish traditional for their culture were reproduced with great skill. Tattoos on the hands of Xinjiang mummies* are simple in execution and consist of one repeated sign (these are, as a rule, geometric figures; in one case, stylized fish images) (Fig. 12). The tattoos on hands peeking out from under the sleeves of shirts and fur coats provided much more information about a person than his/her physical type. It is unlikely that the meaning of these images will ever become understandable to us, but one of the purposes of tattoos is quite transparent—to designate a person’s membership of a certain community.

The Pazyryk people were a multi-component and multi-ethnic entity. So, what united them and distinguished from the surrounding cultures and peoples? Their habitat, subsistence, and lifestyle were identical to those of their neighbors in the Sayan Mountains, Transbaikalia, and the Mongolian steppes and mountains. It was not these basic components that determined the originality of the Pazyryk culture, but its unique cultural baggage and historical background. On this foundation, the Pazyryk people created their own conception of the world, reflected in their style, by which we mean the unity of all components of the culture—body-tattoos, decorations of clothes and horse harness, appliqué decorations on felt items and household utensils, their hairstyles, and their mummification techniques, etc., which distinguished the Pazyryk people from others.

Conclusions

The question arises as to whether the wooden items— figurines of animals, birds, and fantastic creatures*, the main features of the “Pazyryk style”—were manufactured for everyday wear. Many experts doubt this. But since none of the Pazyryk burials yielded metal (gold) analogs of at least one wooden item from this set of ornaments, it is quite likely that all these things, beautifully made of cedar, served their owners not only during the funeral, but also in everyday life**. These items could have been reproduced many times. Most likely, they were used as everyday ornaments, lightweight and comfortable to wear. They could be lost, broken, repaired, or produced again in any quantity***. A low-ranking member of society could have ornaments as fine as a high-ranking one; everything depended only on the skill of the carver. Ordinary burials often contained wooden ornaments made with exceptional skill and talent (Kubarev, 1991: 116, fig. 29; p. 122, fig. 32; 1992: 96, fig. 28; p. 105, fig. 33; and others). All the members of society, including children, had such much-significant figurines; they served as identification marks for the Pazyryk people, and determined their style. Notably, both in the ordinary and in “royal” mounds, these items were coated most often with gold foil, less often with tin foil. The golden sheen is characteristic of items of the Pazyryk culture; but at the same time, fullweight gold jewelry was absent in the burials, and this fact cannot be the result of looting. In our opinion, the Pazyryk culture was not wasteful: in order to add golden luster to the product, the Pazyryk people used gold foil. Almost weightless, it was used everywhere and in large quantities, equalizing all members of the society*.

Any culture is determined not by the number and wealth of imported items, but by the people who practiced this culture. The view of the world developed by the Pazyryk people disappeared along with them. The only way to recreate this view is through interpretation of the images they have created. We do not know why the creators of this peculiar art valued them, but we are trying to understand it, relying on mythology, folklore, and epics. We can read any “text” consisting of images of animals, birds, fish, imaginary creatures, and it seems that we have found a clue to unraveling this language. But is it one? Unfortunately, we create the mythology of the Pazyryk people ourselves. With regard to the Pazyryk culture, this became clear after the publication of the work of D.V. Cheremisin “The Art of the Animal Style in the Burial Complexes of the Ordinary Population of the Pazyryk Culture” (2008), in which the author perfectly applied a research approach to the pictorial corpus of the animal style as a source containing a certain “mythological text” conveyed in the language of images. Both the approach itself and the author’s hypothesis, according to which “the motifs of images in the animal style manifested in the ensembles of ritual attributes are determined by myth and represent the language of the burial complex, which proclaimed the ideologemes common to the society”, do not give rise to any objections (Ibid.: 5). However, the analysis of the images themselves showed that each of them is ambivalent, and the place that this or that character will take in the picture of the world of the Pazyryk people depends only on the erudition and will of the author of the concept. But the images of animals, birds, and fish may reflect concepts unknown to us, not related to their natural animal essence.

Leaving aside the semantics of images of the Pazyryk art, we would like to focus on the style, which is obvious. In contrast, the semantics will always serve as a stumbling-block, owing to our lack of knowledge in this area. This lack gives rise to many interpretations and to

*A gold earring, silver buckles with a scene of a lion torturing a fallow deer from the 2nd Pazyryk mound, and precious woolen fabrics and a carpet from the 5th Pazyryk mound could have been part of the loot from the Achaemenid treasuries during the Macedonian expansion. In this period, the jewels of the Ancient East were moved over huge distances and, together with the invaders, ended up in Central Asia (Litvinsky, Pichikyan, 1993: 88).

the reduction of all images and compositions to a single conception (upper, middle, and lower realms, and scenes of torment, symbolizing the cycle of life-death). The style does not explain anything, but the Pazyryk culture is singled out and exists both literarily (in scientific works) and in reality, thanks to this particular style. Pieces of applied art of the Pazyryk people have become their identification mark. The totality of customs of one nation is always marked by some style (Levi-Strauss,

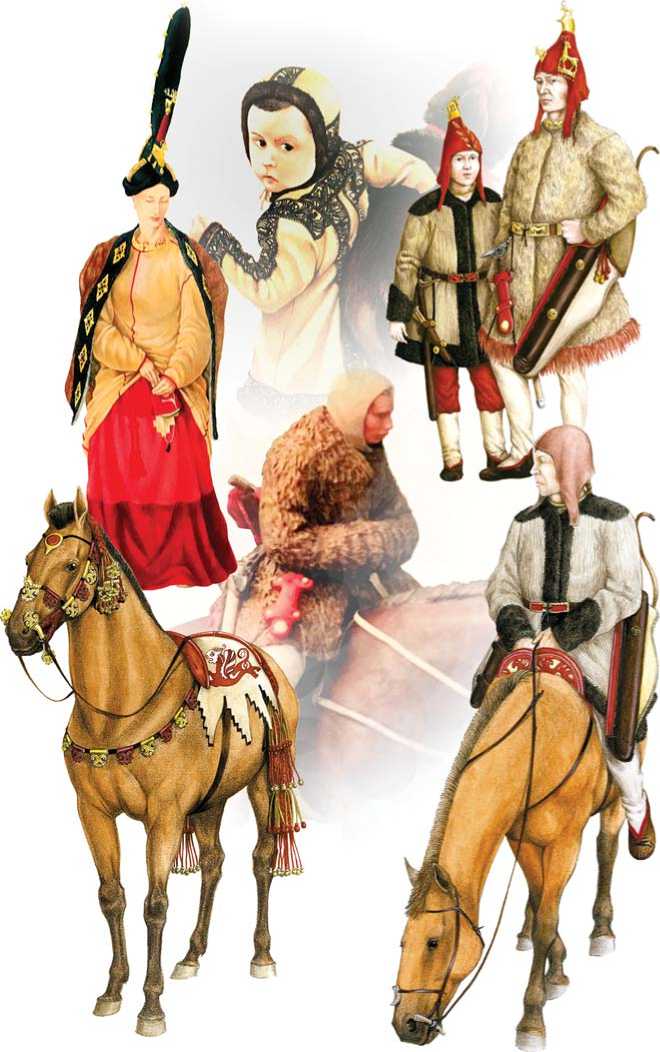

1984: 78). Style is a visualization of culture (Fig. 13). It would not be an exaggeration to say that we would immediately recognize a Pazyryk person, but why? Because the appearance of any of them—a man or a woman, young or old, noble or ordinary—is stylistically consistent; they all are alike in their main characteristic, despite the differences in status. Why is style so important? Comparison of the Pazyryk culture with the culture of the Xinjiang oases population has clearly shown that certain

Fig. 13. Pazyryk people. Visualization of the Pazyryk style. Reconstructions by D.V. Pozdnyakov.

categories of things reveal an unconditional similarity and suggest the kinship of cultures and people; but when the concept of style is introduced, it becomes obvious that we face completely different people with different cultural traditions. Images of animals, birds, and fish, both real and fantastic, repeated in original combinations and ornamental compositions on everything—from dishes (handle of a wooden vessel from mound 1 of the Ak-Alakha-3 cemetery, leather applications on clay and leather vessels, etc.) to the ornaments and decorations of people, horses, coffins, felt items, clothes, tattoos on the bodies of men and women— make the Pazyryk people members of one society, unique and recognizable in every feature.

Acknowledgement