The role of the investment projects in the renaissance of Syrian cultural heritage

Автор: Alghafri M.A.

Журнал: Теория и практика современной науки @modern-j

Рубрика: Международные экономические отношения

Статья в выпуске: 2 (44), 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The objective of this paper is to examine the issues and options related to the appraisal of projects and the selection of policy measures in the cultural heritage sector in Syria. The paper starts with the issue of whether cultural heritage has an economic value and provides a survey of concepts and methods in the valuation of heritage assets. Then it examines how cost benefit analysis can be used in the evaluation and selection of cultural heritage project and the issue of financing of cultural heritage projects in Syria.

Investment, financing, cultural heritage, heritage value, economic development, syria

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140274317

IDR: 140274317

Роль инвестиционных проектов в ренессансе сирийского культурного наследия

Целью данной работы является изучение вопросов и вариантов, связанных с оценкой проектов и выбором политических мер в секторе культурного наследия в Сирии. Статья начинается с вопроса о том, имеет ли культурное наследие экономическую ценность, и содержит обзор концепций и методов оценки активов наследия. Затем рассматривается вопрос о том, как анализ затрат и выгод можно использовать при оценке и отборе проектов культурного наследия, а также вопрос финансирования проектов культурного наследия в Сирии.

Текст научной статьи The role of the investment projects in the renaissance of Syrian cultural heritage

Introduction. The evaluation of investments and the identification of financing cultural heritage projects becomes a priority. This does not imply that only economic factors matter for such projects; quite the opposite. It implies that the allocation of investment funds between competing objectives, the selection and prioritization of projects, the financial structure, and the implementation and governance of such projects are important challenges that need to be addressed [1,21]. However, such challenges are very different from those encountered when we have to evaluate and select projects in the real economy, such as industrial or even infrastructure projects. The economic impact of cultural heritage projects is non-tangible and, hence, there are no markets to provide an objective valuation of goods and services delivered. The lack of markets and the difficulty in the quantification of goods and services provided by cultural heritage projects makes selection difficult or sometimes impossible. This approach does not deny the cultural, artistic, archaeological, architectural, and historic value of heritage assets; it complements it with the “economic value” or the “economic dimension”. It offers a tool for making the allocation of investment funds easier, it provides an “objective” assessment of what the people and markets consider valuable and, hence, what the society considers worth spending scarce public resources on[2,5]. Economics is considered a narrow discipline, ignoring or incapable of taking into account the many facets of value of a cultural asset. Putting an economic value on cultural heritage objects is considered by purists as sacrilegious or blasphemous. Art and culture, they claim, has no economic value; has only historical, archaeological, artistic, intrinsic, but not economic value [5,6].

This paper aims to examine how recent advances in applied economics can be utilized in the evaluation and selection of investments in cultural heritage projects in Syria, in addition to identify the responsibility to evaluate and investment of cultural heritage projects in Syria. This approach has been extensively used for the evaluation of investment policies in the areas of environment and climate change.

Approaches for valuing cultural heritage. Cultural heritage is a typical public good. Economics provides a clear definition of a public good as having two important characteristics: it is (a) non-excludable, and (b) non-rival in consumption. These concepts have been used extensively in public economics to analyze public policy options [3,11]. Governments and non-governments or private not-for-profit organizations may step in as providers of cultural heritage goods if the private sector is not willing to do so. However, the choice of the amount of cultural heritage goods and services to be provided and the amount of expenditure needed to facilitate that supply remains unsettled. Our world is one of limited resources, hence, tradeoffs must be made either within the cultural heritage sector or across economic sectors and among competing objectives. However, when the evaluation of projects and activities involves experts from different disciplines, an opportunity is provided to open up the dialogue in expectation that there is a lot of common ground between economic and cultural approaches in the valuation of heritage. It can be claimed that an economic assessment of a heritage asset, if well done, has a lot to contribute to decisionmaking in public policy and expenditure selection in the heritage sector [4,5]. This section provides a brief overview of these concepts and a broad conceptual framework for assessing value. Speaking about the economic value of a heritage asset, one does not deny the cultural value of the asset, but it adds to it an economic dimension, the economic value, that is central to the choice of allocating scarce resources and to public policy decisions. The problem of determining economic value becomes more complex when it becomes apparent that a distinction must be made in economic value between individual and collective value and between private and public value [10,13].

Valuation methods and techniques. The standard methodology for calculating the economic value of an asset is based on the derivation of a demand curve for its services or the preferences for its existence. Following the identification of the components described above, an analyst will list expected project impacts, classified according to the type of value they are likely to affect and the beneficiary group [7,12]. Also, in some cases, heritage benefits can be measured directly, while in other cases benefits are deduced and valued from observed behavior, or measurement relies on direct questioning of consumers. A list of methods with a brief description of each is given next (Table 1).

Table 1- The valuation methods of cultural heritage assets [9,10,11,14,19].

|

Market price methods |

The benefits of a heritage project enter the market and could be quantified and priced in the market. For example, in a cultural heritage project that may induce economic activities in tourism, standard techniques can be used to value these benefits. However, the problem arises in the quantification of these services, not in their valuation. |

|

Replacement cost method. |

The cost of replacing a good is often used as a proxy for its value. However, given that heritage assets are essentially irreplaceable, replacement is not an appropriate approach and in such cases the appropriate approach is one of cost-effectiveness rather than of cost benefit. |

|

Travel cost method. |

This method infers value from observed consumer behavior. It derives the consumer’s demand curve for the asset’s services using information about the visitors’ total expenditure to visit a heritage site or a heritage asset to “consume” heritage services, thus deriving the consumer’s demand curve for the site’s services. From this demand curve, the total benefit visitors obtain can be calculated. |

|

Hedonic pricing. |

Starting from the observation that market prices are in fact prices of a bundle of attributes, the use of hedonic methods is based on the principle that by examining the difference in market prices of similar goods having different attributes, one can infer the value of non-market attributes, such as environmental quality. For example, a home with a sea view may have a different market price that an exactly similar home without a view. Hedonic techniques allow this effect to be measured, holding all other factors constant. |

|

Contingent valuation method. |

This is the most popular method used in valuing cultural heritage assets. It has been employed for the valuation of aesthetic benefits, existence values, as well as other benefits such as to value publicly or privately provided goods such as water supply and sewerage in areas without existing services. |

Funding model. The funding model of heritage projects is an important issue. Traditionally, financing of investment in culture and heritage used two main modes: (a) public funding, either national or local, as public investment or as operational expenditure of public organizations, and (b) private funding from private individuals or from charities in the form of donations. However, currently, public funds are under severe stress from competing objectives, and charity funds are dwindling. In addition, to ensure that heritage assets and archaeological sites will remain available for many years to come, operation and maintenance expenditures should be foreseen, in addition to investment funds. Hence, given the shortage of public and charity funds, innovative tools and models for heritage asset financing that overcome the constraints and barriers present in almost every country are needed [6,13]. However, with stringent fiscal constraints, financing heritage projects from public funds becomes a nearly impossible task, and there is a clear need for financial innovation and for new financing instruments to be used in heritage project attracting private sector funding. The heritage sector offers an uncharted potential for partnerships. In fact, the use of Public Private Partnerships in the cultural sector is relatively recent, and many countries do not have the appropriate legislations in place, or the legal and administrative conditions, to allow the use of Public Private Partnerships in heritage projects. Public Private Partnerships can bridge the funding gap of public entities, provide interesting investment opportunities for the private sector, but they require the development of legal, institutional, policy, and administrative conditions in order to offer opportunities to develop capacities, transfer of knowledge and excellence, and foster entrepreneurship in local communities. The experience so far shows that Public Private Partnerships, if properly designed, allow the public sector to participate in compliance with its own regulations, practices, and financial resources and the private sector to bring management expertise, knowhow, and financial and technical inputs [3,7].

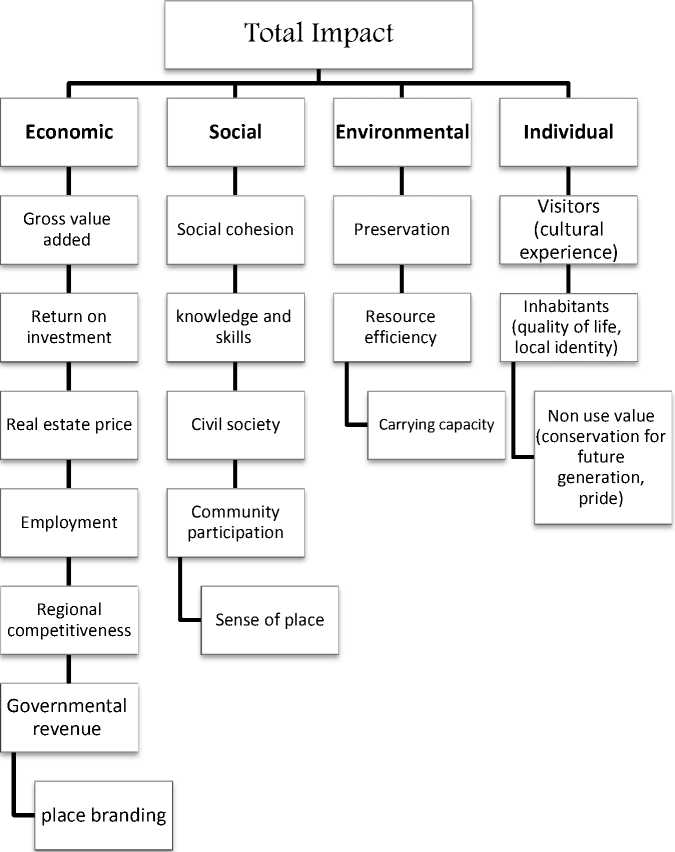

The cost benefit analysis method in appraising cultural heritage projects. Cost benefit analysis (CBA) is an economic methodology or a framework to assess the economic impacts of a project or policy intervention from the perspective of society. CBA is widely used in the evaluation of public investments and policies. It involves measuring the benefits and costs from an activity to the society using “money” metric and aggregating those streams of benefits and costs to infer the economic and social impacts of these projects or policies to society [20]. Conducting a CBA would also provide information on what it would take to make the potential benefits of an activity actually materialize. CBA can be undertaken at any stage in the project cycle [16]. Conducting a CBA of a heritage project would require an analysis of the policy, legal and institutional framework, baseline data for measuring costs and benefits, an analysis of alternatives and an impact assessment of the proposed activities [17,22]. Measuring project costs is easier. Two categories of costs must be considered when evaluating projects involving cultural heritage. The first is the cost of the proposed project activities. The second is the opportunity costs of resources employed in the project. However, measuring project benefits may be quite difficult with respect to quantification as well as to valuation. A broad categorization of a heritage project’s benefits is given in (Figure1).

Figure1- Decomposing total impact of a heritage project [8,9,15].

There is a clear need to develop conservation models that are capable of being enhanced in the long term and become self-sustaining. This will need the full support of the local communities and owners of heritage properties [9,10]. Projects will also have a better chance of success if they encourage publicprivate cooperation in the financing and implementation of conservation projects. This may require, on the public sector’s side, improvement in the laws and regulatory environment, and clarifications in institutional roles and responsibilities involving heritage conservation. Clear codes and standards relevant to heritage conservation will also have to be made. Cities that have an environmental impact assessment procedure in place to approve development projects can easily include heritage criteria as an integral part of the assessment. On the private sector’s side, there is a need for providing financial, technical, and other inputs to the project to enhance conservation efforts. Gathering background information and project formulation itself can be taken up by private sector entities.

Conclusions. The evaluation of investment and policy measures, and the identification of sources of financing of cultural heritage projects is a requirement. Recent advances in applied and environmental economics and their application in the evaluation of public policies and in the selection of cultural heritage projects provide solutions to this challenge. Central to this approach is the valuation of goods and services provided by cultural heritage projects. Admittedly, the valuation of cultural heritage assets is still quite controversial. However, when we put an economic value to cultural heritage assets, the sin we commit is of the same kind, but perhaps greater in degree, to the one we commit when we measure GDP as an indicator of well-being of a country or the economic value of a food-producing hectare of land.

The objective of this paper is to examine the issues and options related to the appraisal of projects and the selection of policy measures in the cultural heritage sector. The discussion in this paper can be summarized as follows. First, cultural heritage assets have an economic value. Denial of this reality by adherence to old fashioned perceptions deprives societies of an important development resource and concurrently leads to devaluation and destruction of the same cultural heritage due to inability of budgets to bear the financial burden of maintenance. Second, in the modern conception of economic development, cultural heritage is recognized as both an engine of growth and a catalyst for economic and social development. The challenge is the successful integration of the use of cultural heritage in the economic and social environment with an effective change management framework. Third, the international experience is rich in examples, where the successful integration of cultural heritage into the economic development strategy has a strong positive impact at local and national level.

Список литературы The role of the investment projects in the renaissance of Syrian cultural heritage

- Boardman A.; D. Greenberg; A. Vining and D. Weimer. Cost Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice/ A.; D Boardman, A. Vining and D. Weimer, Pearson International Edition, London, UK, 2014. P. 67- 73.

- Gittinger, J. P. Economic Analysis of Agricultural Projects/ J. P. Gittinger, The Johns Hopkins University Press for The World Bank, 2nd Edition, 1982. P. 45.

- Hanemann, W.M. The Economic Theory of WTP and WTA" in Valuing Environmental Preferences, by Ian J. Bateman and Kenneth G. Willis (Editors), Initiative for Policy Dialogue Series, Oxford University Press, 2002. P. 23.

- huaxia, Syria's tourism sector shows improvement in past three years [Electronic resource]. Access mode: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-05/10/c_137168033.htm [Accessed 10/09/18].

- Hutter, M. and D. Throsby. Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics, and the Arts /M. Hutter, D. Throsby, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008. P. 123.

- Lazanyi, O. Multidisciplinary methodology development to measure socio-economic impacts of cultural heritage EHHF Task Force meeting, 16-17 September 2015, Brussels. 2015.

- Mergos, G. Socio-economic Evaluation of Investments and Policies / G. Mergos, Vol. 2 Applications, Benou Publishing, Athens (in Greek). 2007. P. 83.

- Midel east, Syria Preparing Several Projects to Attract Russian Investors [Electronic resource]. Access mode: https://sputniknews.com/middleeast/201708231056724915-syria-tourism-investment/ [Accessed 10/09/18].

- Mourato, S. and M. Mazzanti. Economic valuation of cultural heritage: evidence and prospects / S. Mourato, M. Mazzanti. In: Getty Conservation Institute (2002) Assessing the Value of Cultural Heritage. Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles. 2002. P. 54- 78.

- Navrud, S. and R.C. Ready. Valuing Cultural Heritage: Applying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings / S. Navrud, R.C. Ready, Monuments and Artifacts. Cheltenham: Ed-ward Elga, 2002. p. 141.

- Pagiola, S. Economic Analysis of Investments in Cultural Heritage: Insights from Environmental Economics / S. Pagiola, Environment Department, The World Bank, June 1996 (mimeo, 1996. P. 118.

- Palmquist, R. B. Hedonic methods in J. B. Braden and C. D. Kolstad (eds.). Measuring the Demand for Environmental Quality / R.B. Palmquist, B. Braden and C. D. Kolstad North Holland, Amsterdam. 1991. P. 178.

- Plaza B. The Return on Investment of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao // International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. (2006) Vol. 30(2). P.452-467.

- Ready R.C. and S. Navrud, Why Value Cultural Heritage? in Navrud S. and Ready R.C. (Editors) Valuing Cultural Heritage - Applying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings, Monuments and Artifacts, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., UK. 2002. P. 48.

- Rizzo, I. and A. Mignosa, Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage/ I. Rizzo, A. Mignosa, Edward Elgar Northampton, Massachusetts, USA. 2013. P. 69- 99.

- Rizzo, I. and D. Throsby Cultural heritage: economic analysis and public policy, in Victor Ginsburgh and David Throsby (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture / I. Rizzo, D. Throsby. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland, 2006. P.983-1016.

- The Syria Report: Projects Licensed by Investment Body Decline 74% y-o-y [Electronic resource]. Access mode: http://www.syria-report.com/news/economy/projects-licensed-investment-body-decline-74-y-o-y. [accessed 12.09.2018]

- Throsby, D. Cultural sustainability", in Towse (ed.) (2003), A Handbook of Cultural Economics / D. Throsby, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2003. p. 183-186.

- Throsby, D. Determining the value of cultural goods: how much (or how little) does contingent valuation tell us? // Journal of Cultural Economics, (2003). vol. 27(3-4) p. 275-285.

- Throsby, D. Investment in Urban Heritage: Economic Impacts of Heritage Projects in FYR Macedonia and Georgia / D. Throsby, Urban Series, Development Knowledge Papers, The World Bank, Washington DC. 2013. P. 139.

- Throsby, D. (2016). Investment in urban heritage conservation in developing countries: Concepts, methods and data City // Culture and Society, 2016. Vol. 7 (2) 81-86.

- Towse, R. Handbook of cultural economics / R. Towse, R 2nd edition. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. 2013.p. 86.

- Yazigi, J. Syria's War Economy, European Council on Foreign Relations, London. [Electronic resource]. Access mode: (http://www.ecfr.eu/page//ECFR97_SYRIA_BRIEF_AW.pdf; [accessed 12.08.2018]