The Russia-USA legal dispute over the straits of the Northern Sea Route and similar case of the Northwest Passage

Автор: Andrey А. Todorov

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Economics, political science, society and culture

Статья в выпуске: 29, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article examines the legal status of the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which has been a subject of dispute between the Soviet Union\Russia and the United States for over fifty years. The main legal issue of the analysis is the question whether straits of the Northern Sea Route are international, where the freedom of navigation applies, or whether the straits are internal waters of Russia and they are subjected to national rules of navigation. The case of the Northern Sea Route straits is considered from a historical perspective and with references to relevant provisions of the contemporary international law of the sea. A similar dispute between Canada and the USA over the Northwest Passage is assessed as well. The author concludes that the USA has a disadvantageous position in the disputes due to difficulties in proving that both routes can meet necessary criteria for international straits developed by the international law. So far, the debate on legal status of the NSR waters is more of theoretical nature and has no practical implications. However, the situation might change with the Arctic sea ice melting and Russia planning to use the NSR on a much larger international scale.

The Arctic, the Northern Sea Route, Russia, the USA, international straits, freedom of navigation, law of the sea, internal waters, sovereignty, Canada, the Northwest Passage

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318560

IDR: 148318560 | УДК: [341+327](47+73)(045) | DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2017.29.74

Текст научной статьи The Russia-USA legal dispute over the straits of the Northern Sea Route and similar case of the Northwest Passage

The Northern Sea Route dispute in retrospective

Over the last few decades the Arctic Ocean has experienced a rapid reduction of sea ice. These changes have opened previously inaccessible shipping lanes. First and foremost, this relates to two Arctic routes — the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and the Northwest Passage (NWP). These maritime lines could potentially be an alternative to traditional southern routes through Suez and Panama channels. At the same time the legal status of the waters constituting the both passages remain disputable. The essence of the dispute can be expressed in a simple question — whether and in what extent there is freedom of navigation in the waters of these routes or they are sovereign waters of the coastal states and are subject to national legislation.

The NSR, sometimes called Northeast Passage, is the shipping route connecting Europe and Asia, north of the Russian coast. The NSR has the potential to reduce the distance between Europe and Asia by up to 40 per cent, compared to the contemporary Suez Channel Route (SCR) [1, Hum-pert M., p. 10]. The NSR is not a specific route but a multitude of passageways along the Russian Arctic and therefore covers a vast segment of the Arctic Ocean.

Russia and USA have a long-standing dispute over the legal status of the Northern Sea Route that have been impacting the bilateral relations in the Arctic since 1960-s. Russia claims the NSR to be a national transport communication subject to national legislation on historical grounds.

USA challenge such approach and consider some of the straits of the NSR — in particular, straits of the Karsky Sea, the Laptev and Sannikov Straits — to be international, to which freedom of navigation applies.

In the mid 20 century there was an incident in the waters of NSR leading to exchange of diplomatic notes between USA and USSR. In 1963 without an advance permission of the Soviet authorities the USCGC Northwind collected data in the Laptev Sea; during the following summer the USS Burton Island surveyed in the East Siberian Sea. Reacting on this voyage the Soviet Union in its diplomatic note by 21 July 1964 argued that “...the northern seaway route at some points goes through Soviet territorial and internal waters. Specifically, this concerns all straits running west and east in the Karsky Sea. In as much as they are overlapped two-fold by Soviet territorial waters, as well as by the Dmitry, Laptev and Sannikov Straits, which unite the Laptev and Eastern Siberian Seas and belong historically to the Soviet Union. Not one of these stated straits, as is known, serves for international navigation. Thus, over the waters of these straits the statute for the protection of the state borders of the USSR fully applies, in accordance with which foreign military ships will pass through territorial seas and enter internal waters of the USSR after advance permission of the Government of the USSR”1.

United States responded with a note, in which stated its position: “With respect to the straits of the Karsky Sea described as overlapped by the Soviet territorial waters it must be pointed out that there is a right of innocent passage of all ships through straits used for international navigation between two parts of the high seas and that this right cannot be suspended”2.

In 1967 the United States planned navigation by the U.S. Coast Guard icebreakers Edisto and East Wind in the waters off the coast of Novaya Zemlya and Severnaya Zemlya and in the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea. Due to severe ice conditions on the route the ships passed through the Karsky Sea and were proceeding towards the Vilkitsky Straits. This resulted in a protest of the Soviet government, considering these actions by USA to be violation of the Soviet regulations. This statement forced US vessels to cancel the planned navigation3.

Since those times both sides maintained their respective positions on the status of the straits of the Northern Sea Route. In 1980s Soviet Union to strengthen its sovereignty in the Arctic waters issued special decree drawing straight baselines in some waters of the NSR thus including them in internal waters on historic grounds4. Current legislation of Russia considers the NSR as national maritime transport route, to which special national rules of navigation apply5. USA, in turn, in its official national policy acts relating to Arctic reiterate, that the freedom of the seas is a top national priority for USA and, accordingly, they treat the Northwest Passage and some of the straits of the Northern Sea Route as straits used for international navigation, to which the regime of transit passage applies6. This stalemate in the approaches to the legal regime of the Arctic shipping routes will likely be influencing the relations of the Arctic states in the coming decades. In the following part of this paper we will discuss the legal status of the NSR with reference to the relevant provisions of the Law of the Sea.

Relevant provisions of the international law

The NSR consists of maritime areas with different legal status. Most of the waters constitute areas, where Russia enjoys sovereignty or sovereign rights — internal waters, territorial sea or EEZ of Russia, but it also includes parts of the high seas. When a strait constitutes parts of the high seas or EEZ there is little to discuss — these waters are subject to freedom of navigation for foreign vessels. Most of the legal disputes arise when straits include territorial sea or are enclosed by straight baselines into internal waters of the coastal state. Here the concept of baselines is of critical importance. All the maritime zones are defined by reference to the baselines established by a coastal state.

The waters on the landward side of the baseline are defined as internal waters. In its internal waters state exercises the greatest degree of control in comparison to other maritime zones. International law provides that internal waters are subjected to the full force of the coastal state’s legislative, administrative, judicial, and executive powers [2, Lasserre F., Lalonde S., p. 32]. The drawing of straight baselines has been the primary mechanism through which international straits have been enclosed within a coastal state’s internal waters. Article 5 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (UNCLOS) provides that the normal baseline is the low-water line along the coast as marked on large-scale charts officially recognized by the coastal state. However, UNCLOS provides that “[i]n localities where the coastline is deeply indented and cut into, or if there is a fringe of islands along the coast in its immediate vicinity, the method of straight baselines joining appropriate points may be employed in drawing the baseline” (Art.7)7.

Moreover, Law of the Sea enables a country to claim title over internal waters on historic grounds if it can show that it has, for a considerable length of time, effectively exercised its exclusive authority over the maritime area in question. Soviet Union used this provision in special Decrees of the Council of Ministers of the USSR of February 7, 1984, and January 15, 1985 to draw straight baselines and claiming White Sea, waters of the Cheshskaya, Pecherskaya, and Baydarata Bays, of the Gulf of Ob and of the Yenisei Bay, the waters of the straits separating Novaya Zemlya, Kolguev, Vaigach, Severnaya Zemlya, Anjou, and Lyakhov Islands, a range of smaller islands from the continent and of the straits separating the foregoing islands, lands, and archipelagos from each other, as historical internal sea waters8. The most influential Russian legal expert in the field of the Law of the Sea A.N. Vylegzhanin elaborates on the argument of historical claim over the waters of the NSR: “In a legal sense, the achievements of the Russian Federation in the Arctic consist, first, in the discovery and exploration of many Arctic spaces and the right of discovery was <…> a sufficient title to extend the authoritative powers of the Russian state to the discovered spaces” [3, Vylegzhanin A., p. 121].

However, there is one more criterion for claiming waters as historical — acquiescence. Coastal state must prove that its exercise of authority has been accepted by other countries, especially those directly affected by it. As we have already noted, Russia's claim over the waters of the NSR straits as historical internal waters is opposed by USA. But at the same time, no other country has joined expressly in the United States’ persistent objection to Russia’s claim of sovereignty over the Northern Sea Route [4, Rossi C., p. 505], so the question remains open.

But even if we consider waters of the straits of the NSR to be internal waters of Russia, we should bear in mind an important limitation of possible infringements of freedom of navigation by coastal states, provided by the UNCLOS. Article 8(2) stipulates that “[w]here the establishment of a straight baseline in accordance with the method set forth in article 7 has the effect of enclosing as internal waters areas which had not previously been considered as such, a right of innocent passage as provided in this Convention shall exist in those waters.” Relating to the legal regime of international straits, it means, that Russia must prove, that those waters have not been used as straits for international navigation before drawing the straight baselines. And here we come to the problem of legal definition of international straits.

Straits are natural maritime passages connecting parts of the high seas, or seas and oceans. Some straits due to their geographical position and importance for international navigation are subject to special international legal regime. UNCLOS does not contain an official definition of international straits. However, there is one developed by legal practice. In 1949 the International Court of Justice decided the Corfu Channel case9, in which it set out the criteria for considering a strait used for international navigation. There are two main criteria:

-

1) the strait must connect two parts of the high seas (geographical requirement),

-

2) and the strait must be used for international navigation (functional requirement — volume of traffic is crucial).

Most experts believe that both a geographical and a functional element must be satisfied for a strait to be qualified as an international one [2, Lasserre F., Lalonde S., p. 34]. Indeed, the Court’s deliberate use of the coordinative conjunction “and” gives equal weight to both criteria. If we apply these criteria to the Northern Sea Route, it will be obvious, that its straits meet the geographical requirement while connecting parts of the high seas or Russian EEZ, which in this context also can be treated as high seas.

Contrary to that, there are ongoing debates on the functional criterion. Some legal experts, primarily from the United States, argue that so long as the body of water can potentially be used for international navigation, the Court’s functional test is satisfied. Others believe that to define a strait as an international, it must be a “useful route for international maritime traffic,” that it must have a history of usage by the ships of foreign nations [5, Pharand D., p. 224]. But then a next question arises: what volume of traffic is sufficient? For example, there is a view that “the sufficiency of the use is determined mainly by reference to two factors: the number of ships using the strait and the number of flag states represented. Both figures should normally reach the order of magnitude shown to exist in the Corfu Channel case. There, the ships using the North Corfu Channel averaged 137 a month, during a twenty-one-month period, and represented seven flag states”. [6, Pharand D., p. 107]

In any case, applying the functional criterion to the straits of the NSR would demonstrate, that before the Soviet government declared some of its waters internal, they were used for international navigation only for few times. Even nowadays international navigation through the NSR is counted literally by several dozens of transits (2014 — 24 vessels, 2015 — 18, only 8 of them are foreign flagged10). So, it would be justified to conclude, that functional requirement is not fulfilled in case of the NSR straits. However, USA maintain their position that some straits can be potentially used for international navigation and thus represent international straits.

Unlike legal definition of an international strait, the legal regime for navigation through such straits is firmly established. Part III of the UNCLOS addresses five different kinds of straits used for international navigation, each with different legal regime:

-

1. Straits connecting one part of the high seas/EEZ and another part of the high seas/EEZ (Article 37 — governed by transit passage).

-

2. Straits connecting a part of the high seas/EEZ and the territorial sea of a foreign state (Article 45(1) (b) — regulated by nonsuspendable innocent passage).

-

3. Straits connecting one part of the high seas/EEZ and another part of the high seas/EEZ where the strait is formed by an island of a state bordering the strait and its mainland, if there exists seaward of the island a route through the high seas/EEZ of similar convenience regarding navigation and hydrographic characteristics (Article 38(1) and Article 45(1) (a) — regulated by nonsus-pendable innocent passage).

-

4. Straits regulated in whole or in part by international conventions (Article 35(c)). The LOS Convention does not alter the legal regime of straits regulated by long-standing international conventions in force specifically relating to such straits. Examples of such straits are the Dardanelles and Bosporus, Baltic Straits and others.

-

5. Straits through archipelagic waters governed by archipelagic sea lanes passage (Article 53(4)).

Most of the straits of the Northern Sea Route and in relation to which USA claim the status of international straits can be attributed to the first category, and thus can be potentially connected with the regime of transit passage. Transit passage applies to straits connecting one part of the high seas/EEZ and another part of the high seas/EEZ and is defined in the LOS Convention as the exercise of the freedom of navigation and overflight solely for continuous and expeditious transit in the normal modes of operation. For warships this means that submarines are free to transit international straits submerged, since that is their normal mode of operation. The right of transit passage “shall not be impeded.” UNCLOS provides certain limitations of the transit passage — all transiting ships and aircraft must proceed without delay; must refrain from the threat or the use of force against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of states bordering the strait; and must otherwise refrain from any activities other than those incidental to their normal modes of continuous and expeditious transit (Article 39(1)).

Transit passage through international straits cannot be suspended by the coastal state for any purpose (Article 44). The state bordering the international strait may designate sea lanes and prescribe traffic separation schemes to promote navigational safety.

Returning to the dispute between Russia and USA on the legal status of the straits of the NSR, it should be noted, that the straits claimed by the United States as international — Dmitry Laptev, Sannikov and some other — connect parts of the high seas or EEZ of Russia. Theoretically, if it is proved that they should be treated as international straits; norms of UNCLOS pertaining to transit passage could be applied to them. But there is one important issue to bear in mind: the regime of transit passage was established only by UNCLOS and there is a legal question if transit passage represents customary law. USA have not yet ratified the UNCLOS, however, the country acknowledges most of the provisions of UNCLOS as reflective of customary international law. Obviously, USA treats the transit passage regime also as customary law. Contrary to that, Canadian lawyers think that the rule may not have had enough support in practice to claim the customary law status [7, Jia B., p. 127]. It is worth mentioning that during the first diplomatic note exchange between USSR and USA on the issue of the legal regime of the NSR straits in 1960-s, Washington argued that straits were subject to “right of innocent passage”. And that is no wonder, because the transit passage regime was introduced only later with the development of the 1982 UNCLOS.

USA may rely on an argument that freedom of navigation existed in the straits of the NSR before 1984 when USSR included them into internal waters. But then another question arises: can a treaty-based provision (transit passage regime, introduced by UNCLOS), which could have hardly evolved into customary law for a short period of time, be claimed by a state, which is not a party to that treaty (USA), retrospectively to a situation, existed prior to the year of this treaty coming into effect (the UNCLOS was enforced in 1994)? The author of this paper believes that it could hardly be done with sufficient legitimacy. The reasoning of USA is however also clear — being a strong supporter of as much freedom of navigation in the World Ocean as possible, the United States aim at providing best opportunities for its naval forces. And in this context transit passage is more in favour for foreign ships navigating through a strait than the regime of innocent passage. However, from the angle of law and consistency, it would be more appropriate for USA to refer to the innocent passage regime.

The regime of innocent passage, rather than transit passage, contains less freedom for foreign vessels and a higher extent of sovereignty of the coastal state. The concept of innocent pas- sage is normally associated with the territorial sea but applies also to certain types of straits — mentioned in the Article 45(1) (b) and Article 38(1). In comparison with transit passage the extent in which the coastal state can interfere with the navigation of a foreign vessel with the innocent passage regime is much higher. This can be evidently shown by a list of laws and regulations that the coastal state can adopt regarding the both regimes: in the innocent passage regime the list is twice as big as for the transit passage. Moreover, innocent passage is not so favourable for naval forces of foreign states as well — e.g. submarines passing through international straits in a regime of innocent passage must navigate on the surface and to show their flag (Art. 20). There is an important difference in the innocent passage through international straits and innocent passage through territorial sea — there may be no suspension of innocent passage through straits (Art. 45).

In any case, today current legislation of Russia considers the NSR as a national maritime transport route. According to Russia, the NSR consists of waters with different legal status, in each of the maritime zones except for the high seas — territorial or internal waters, EEZ or contiguous zone — Russia as a coastal state exercises sovereignty or jurisdiction. Even in the EEZ Russia has special authority according to Art. 234 UNCLOS to adopt laws for prevention of pollution of the sea. These authorities allow Russia to treat the NSR as a single set of waters with national status. The integrity of the Route for the legal regime is supported by the argument by Russia, that navigation in any parts of the NSR which constitute high seas and in which freedom of navigation applies would be not possible for a foreign vessel without entering the territorial sea and internal waters of Russia. The straits, which the USA addresses as international straits, are included into internal waters of Russia. Overall the Northern Sea route, special national rules of navigation apply. One of the essential rules is that a foreign vessel wishing to pass through the NSR must apply for a special admission to the Russian authorities 15 days in advance11.

The main argument for expanding Russian sovereignty over the waters of the NSR is that this route represents very harsh climate and ice conditions. Russia argues that it is the responsibility of the coastal states to ensure safety of navigation there and to prevent possible ecological threats resulting from accidents on the sea, like oil spills, collision of ships etc. To control the navigation and provide vessels with gidrographical, icebreaking and other support the coastal state should obtain all necessary information about the passing vessel. If the vessel fails to meet existing requirements posing threat to the safety of navigation Russia may not allow this vessel to pass through the NSR. Though in reality there were hardly cases of refusal to foreign vessels in transiting the NSR. A. Vylegzhanin believes, that “the principal geographic, climate. political and legal feature of marine areas in the Arctic Ocean lies in the fact, that even in ice-melting conditions a non-Arctic state may safely perform shipping, fishing and other economic activities in such extremely severe polar areas solely with the consent of a relevant Arctic coastal state, relying on its coastal infrastructure, communication technologies, capability to respond to emergency situations, to search for and rescue people and cargo, to eliminate consequences of marine pollution etc”. [8, Vylegzhanin A., p. 6].

Pevek

Murmansk I

Islands

Kara Sea

Tiksi

Nordvik

1 000 km

Internal Waters

Arctic Ocean

SanniApv / Strait (13 m)

Svalbard (Norway)

Laptev Strait (6,7 m)

Franz Joseph

L^Umd

Long Strait (20 m) '

‘Eastern Siberia

Severnaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya

J Amderma ^^•■ V^amalf\p^ 'geninsula v

Vorkuta z

. Dudinka

ViQtjuKj Strait (25 r. lickson .

Khatanga

Sfiolyilsy Strait (37m)

I / Laptev

Cliu^hi

Wrangel Island Sea

• Norilsk Igarka a

XatocHCein

Strait (12 m) (Barents

Zelenyy Mys

RUSSIA

Baseline claimed by Russia Russian baseline contested . by the United States Northern sea Route Northwest Passage

ALASKA (UNITED Лк STATES)

Ирга Strait (21 m)

Kugors^j Strait (12 m)

Figure 1. The Northern Sea Route.

Indeed, navigation in its waters most time of the year is hardly possible without the aids of the coastal state. Foreign ships may have to rely on local icebreakers, ice conditions forecast and other forms of assistance. Some argue [7, Jia B., p. 129], that in such case straits can no longer be treated as natural straits and refer to the 1951 Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries Case on the legal regime of the Indreleia strait. In that case, Norway drew straight baselines to measure its territorial sea claiming that sea space on the landward side of these straight lines were part of its internal waters, while the UK opposed this. The International Court of Justice supported Norwegian position stating that “the Indreleia is not a strait, but rather a navigational route prepared as such by means of artificial aids to navigation provided by Norway” and has a status of internal waters of Norway12. So, following the logic of this decision, if there exists a degree of dependence of navigation on aids of the coastal state it may not be treated as a natural geographical strait at all, but ra- ther some kind of artificially maintained route which can be used by foreign vessels only with the aids of the coastal state. Thus, international rules of transit passage cannot be applied to such routes. However, in case of the Arctic routes question arises, whether this argument can be used by a coastal state if the aid is being carried out not by this state or if it is not needed at all — for example, in case of a foreign icebreaker or vessel of Arctic class.

Similar case of the Northwest Passage

The United States and Canada have also a long-standing dispute over the legal status of the waters of the Northwest Passage between Davis Strait / Baffin Bay and the Beaufort Sea. The NWP is defined as the combination of shipping lanes connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean through the North American Arctic waterways. The Passage has the potential to function both as an alternative to the Suez Canal and the Panama Canal. Potentially the distance between Northwestern Europe and Asia can be reduced by up to 30 per cent, as well as up to 20 percent between East Coast USA and East Asia [9, Hansen С., Gronsedt P., Graversen C., Hendriksen C., p. 14]. In similarity to the NSR, it is not a specific route but a combination of several routes due to the multitude of different straits and waterways.

As in the case of the NSR, there was also an incident in the late 1960-s with a voyage by the US SS Manhattan from the Beaufort Sea through the Northwest Passage to Davis Strait. This trip was perceived by the Canadian government as a direct threat to Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic waters as the US was accused of not having obtained a formal admission of the Canadian authorities for its vessel [10, Rothwell D., p. 338]. At that moment there had been no formal assertion of Canadian sovereignty over all the Passage waters or those surrounding the Archipelago, and that forced the Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau to make a following statement:

The area to the north of Canada, including the islands and the waters between the islands and areas beyond, are looked upon as our own, and there is no doubt in the minds of this government, nor do I think was there in the minds of former governments of Canada, that this is national terrain.13

After a second voyage of the Manhattan through the NWP the Canadian government came up with enacting the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act, which prolonged Canadian jurisdiction over 100 nautical miles from the low-water mark to ensure environmental standards on vessels passing through Canada's arctic waters. The main argument for such action the growing concern for ecological protection of the Arctic. The United States reacted with strongly opposing such measures by Canada. As in the case of the NSR, USA insisted, that the NWP constituted waters to which the freedom of navigation applied [10, Rothwell D., pp. 340–341].

Following the incidents with the Manhattan Canada continued to reinforce its sovereignty over the waters of the NWP. In 1973 Canada claimed the waters of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago to be “internal waters of Canada, on a historical basis, although they have not been declared as such in any treaty or by any legislation.”14 Later on in 1986, after another incident with a United States vessel — icebreaker Polar Sea — sailing through the Passage without seeking an approval of Canada, this claim was formally affirmed by the governmental act establishing straight baselines around the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and thus making it officially internal waters of Canada over which it had complete sovereignty and jurisdiction. The United States reacted with expres- sions of "regret" over the Canadian decision and formally objected in writing to the Canadian ac- tion [10, Rothwell D., p. 345].

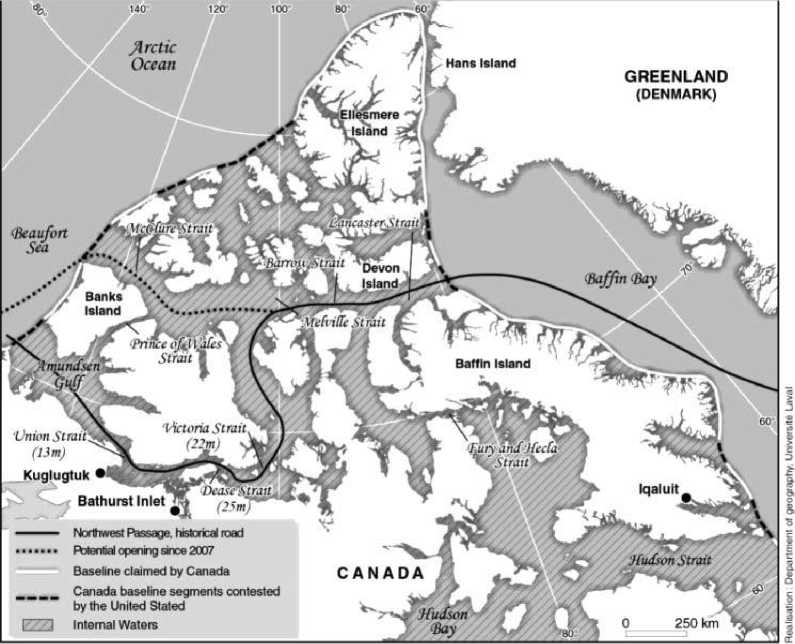

Figure 2. The Northwest Passage.

When considering whether the Northwest Passage is an international strait through which a right of navigation exists, the same provisions of international law apply as in the case of the NSR discussed above. The key point here is also a test of the NWP on the functional criterion of international straits. And alike with the NSR it would be unjust to assert that the NWP can meet the func- tional requirement because of the low number of recorded transits. The total number of passages for the whole history of NWP equals only 236 (end of 2015). A record number (30) of vessels transited through the Northwest Passage in 201215. It is obvious that this would be not enough to complete the functional test of the ICJ.

The history of confrontation between Canada and USA however goes further than that of Russia-USA. Trying to reconcile the differences of opinions Canada and the United States made an “Arctic Cooperation Agreement.”16 This agreement sets forth the terms for cooperation by the two governments in coordinating research in the Arctic marine environment during icebreaker voyages and in facilitating safe, effective icebreaker navigation off their Arctic coasts. There is an important provision in the agreement, that navigation by United States icebreakers within waters claimed by Canada to be internal would be undertaken with the consent of Canada.

However, this agreement deals only with navigation of icebreakers, leaving all other issues of commercial navigation aside. Moreover, the Agreement has not affected the positions of the both countries on the legal status of the NWP. Both countries reserved their views, namely USA — that the NWP is an international strait and that the regime of transit passage applies; Canada — that the NWP constitutes historic internal waters of Canada over which it exercises full sovereignty and that navigation of foreign vessels should proceed with its permission.

Conclusion

The dispute between Russia and the United States over the Northern Sea, as well as between USA and Canada over the Northwest Passage has continued for over fifty years and has involved important issues of territorial sovereignty and national security, on the one hand, and freedom of navigation — on the other. The choking point of the dispute is the legal status of the straits of both passages. The opposing sides rely upon different legal arguments which became possible since the UNCLOS has certain lacunae in terms of providing a clear vision of what international straits really are. Nevertheless, in the author’s opinion, Russia and Canada have stronger positions due to the fact that both routes, especially the NSR remain to be used mainly as internal transport communications for domestic purposes and have a low record of international passages. This makes it hard to assert that these passages would meet a functional criterion of international straits, developed by legal practice. Moreover, even when a foreign vessel passes through these Arctic routes, it strongly depends on the aids provided by coastal states — gidrographical, ice- breaking, meteorological and other services. The dependence of the routes on the aids by a coastal state enables to draw analogy with the Indreleia strait case, when the International Court of Justice classified this route as internal waters of Norway.

In any case, if the Northern Sea Route, as well as the Northwest Passage, due to severe climate and ice conditions and lack of developed infrastructure, is not involved on a large scale into the international navigation, the debate on legal status of its waters is more of theoretical nature and so far, has no practical implications. However, climate is rapidly changing and ice in the Arctic is melting, the navigation season is becoming longer. On that background Russian authorities plan to increase the potential of the Northern Sea Route as international maritime route connecting the markets of Asia with Europe171819. The growth of international navigation through the NSR would mean new arguments for USA insisting that straits of this route are international. It also means that all countries and stakeholders interested in using the Northern Sea Route would need to reach some sort of agreement on the terms of navigation in its waters that would, on the one hand, benefit the interests of free and expedite passage of foreign flagged trade vessels and, on the other hand, have a due regard to the sovereignty and security concerns of Russia.

Список литературы The Russia-USA legal dispute over the straits of the Northern Sea Route and similar case of the Northwest Passage

- Humpert M., Raspotnik A. The Future of Arctic Shipping. The Arctic Institute, Washington, 2007. 20 p.

- Lasserre F., Lalonde S. The Position of the United States on the Northwest Passage: Is the Fear of Creating a Precedent Warranted? Ocean Development and International Law 44: 28–72 (2013).

- Vylegzhanin A. Features of the Legal Regime of Subsoil Use in the Arctic. International Legal Fundamental Principles of the Subsoil Use: Manual. Ed. A. Vylegzhanin. Moscow, Norma (2007). [In Russian]

- Rossi Ch.R. The Northern Sea Route and the Seaward Extension of UtiPossidetis (Juris). Koninklijke Brill Nv, Leiden, 2014. pp. 476–508

- Pharand D. The Arctic Waters and the Northwest Passage: A Final Revisit. Ocean Development and International Law 38 (2007)

- Pharand D. The Northwest Passage in International Law, 17 CAN. Y.B. INT'L L. 99, 100-01 (1979).

- Bing Bing Jia The Northwest Passage: An Artificial Waterway Subject to a Bilateral Treaty Regime? Ocean Development and International Law 44: 123-144 (2013).

- Vylegzhanin A. Introduction in International Cooperation in the Sphere of Environmental Protection, Preservation and Sustainable Management of Biological Resources in the Arctic Ocean. Materials of the International Science Symposium, ed. A. Zagorsky and A. Nikitin. Moscow, Russian Political Science Association, Russian Political Encyclopedia (2012) [In Russian]

- Hansen С. Gronsedt P., Graversen C., Hendriksen C. Arctic Shipping — Commercial Opportunities and Challenges. Ed. Carsten Ørts Hansen. The Arctic Institute. 2016. 94 p. URL: https://services webdav.cbs.dk/doc/CBS.dk/Arctic%20Shipping%20-%20Commercial%20Opportun ities%20and%20Challenges.pdf (Accessed: 18 October 2017)

- Donald R. Rothwell, The Canadian-U.S. Northwest Passage Dispute: A Reassessment, Cornell, International Law Journal, Vol. 26. Iss. 2. Pp. 331–372. URL: http://scholarship.law.cornell. edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1309&context=cilj (Accessed: 18 October.2017)