The strength of the fragrance for one and a half thousand years: agarwood in the Japanese art of incense

Автор: Voytishek Elena E., Rechkalova Anastasia A.

Журнал: Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: История, филология @historyphilology

Рубрика: Культура и филология стран Восточной Азии

Статья в выпуске: 10 т.19, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article gives a brief overview of the genesis of the development of incense culture in Japan through the determining function of aromatic wood in Buddhism, as well as the significance of Japanese classifications of agarwood (aquilaria) species which were developed in the 16th - 17th centuries. Japanese masters invented ways of coding fragrances of aromatic wood through their characteristics of tastes and place of growth, as well as using metaphorical and figurative-symbolic meaning of each name. These techniques played a key role in the history of the traditional art of koudou (‘way of fragrance’) and in the development of female education during the Edo period (1603-1867). Based on the analysis of written sources and museum collections, two classifications were studied, which are still used in Japan when assessing the quality of aromatic wood and wood products: a list of ‘61 kinds of aromatic wood’, developed using associations of odours with significant phenomena in Japanese society as its foundation - calendar holidays, religious concepts, political and literary characters, as well as the system of ‘Six Countries - Five Flavours’, which was based on geographical factors and the principle of reliance on taste and olfactory receptors.

Agarwood, aquilaria, japan, awaji island, classification of aromatic wood, koudou incense art ("the way of fra-grance"), buddhism

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147220391

IDR: 147220391 | УДК: 008 | DOI: 10.25205/1818-7919-2020-19-10-117-129

Текст научной статьи The strength of the fragrance for one and a half thousand years: agarwood in the Japanese art of incense

The emergence of aromatic raw materials of plant and animal origin in Japan is associated with the penetration of a whole complex of ideological, religious and cultural borrowings from China, Korea and the southern tropics in the 6th – 7th centuries, which, in turn, was a result of the formation and development of trade and economic ties in the region. In addition to various parts of plants – flowers, fruits, roots, leaves, resin used as aromatic substances, the incense of animal origin (ambergris, musk, civetin, etc.), as well as minerals, shellfish, and others were widely used in Japan.

However, among the aromatic substances, wood, even today rightfully occupies the most honourable place. Since ancient times, various types of wood of aromatic trees has been highly valued in Japan, many varieties of which grow in the tropical zone of Southeast and South Asia. Just like in Asia, wood of the agar tree (Japanese 沈香 jinkou, or 沈水香木 jinsui-kouboku, meaning ‘the fragrance sinking [in water] / aromatic tree’) 1, has always held the highest status in Japan, which remains to this day. The finest types of this aromatic wood exude the exquisite scent of 伽羅 kyara (in Sanskrit ‘black agar wood’, ‘fragrance’). Over time, an entire system of combining various types of aromatic components was developed, and criteria for evaluating the merits and scope of a particular aroma were formed. The ability to give various types of fragrances exquisite names with deep ideological, philosophical and literary connotation was an especially valued skill, which was also reflected in a large number of classifications of fragrant wood and corresponding fragrances in the history of Japanese culture.

The origins of the use of aromatic aquilaria wood

According to the ‘Chronicle of Japan’ ( 日本書紀 Nihon shoki , 720), the use of aromatic wood in the Japanese archipelago began during the era of Empress Suiko (554–628), when a whole piece of agarwood (aquilaria) was washed ashore on the island of Awaji 2, which, due to its unusual qualities, was then sent to the imperial court [Nihon shoki, 1997. Vol. 2. P. 91]. There are also written records attesting the fact that Prince Shotoku Taishi ( 聖徳太子 , 574–622) respectfully accepted the gift of the coastal inhabitants of Awaji island, while Empress Suiko in the 3rd year of her reign (595) ordered a Korean master from Baekje to carve a statue of the Kannon Bodhisattva out of this wood, which was later assigned to the Hisodera Temple in Yoshino ( 吉野比蘇寺 ). For example, this famous episode of the efforts of the Japanese court to strengthen Buddhism is mentioned in the book ‘Biography of Shotoku Taishi’ ( 聖徳太子伝暦 Shotoku Taishi denryaku ) 3. Based on this chronicle, a series of paintings ‘Illustrated Biography of Shotoku Taishi’ was created in 1069, which were originally placed on the door panels of one of the pavilions of the Horyuji Temple (Fig. 1) 4.

The fate of the historical piece of aromatic aquilaria wood, found off the coast of Awaji island in 595 is also noteworthy; sources claim that during the Asuka period, it appeared in the capital’s Horyuji Temple ( 法隆寺 ), founded in the early VII century by Prince Shotoku Taishi. Since then, the history of the ancient Horyuji Temple is inextricably linked with the history of the development of aromatic plants and trees in Japanese culture, and the study of the properties and functions of aromas in religious and everyday life spheres [Ota Kiyoshi, 2001. P. 30–31]. Like so, an entry in the consolidated register of documents ‘Description of the history and property of the Horyuji Temple’ ( 法隆寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳 Houryuji garanengi narabini ryuuki shizai chou) 5 has been preserved that testifies to the active trade and economic activities of the temple and its ceremonial needs.

Along with Horyuji, another temple in Nara played an outstanding role in spreading the tradition of using incense, namely the Buddhist Todaiji Temple ( 東大寺 ) 6. In the national treasury Shoso-in ( 正倉院 ), a fragment of aquilaria wood (the best variety with the kyara scent) has been kept on its territory for a long time, which has two names – 黄熟香 oujuku-kou (‘ripe yellow aroma’) and 蘭奢

待 ranjatai (‘to receive an exceptional long-awaited aroma’). With the characters of ranjatai , it is customary to include the concealed characters of the name of the Buddhist Todaiji Temple.

Fig. 1. Panel № 4 ‘Illustrated Biography of Prince Shotoku’, ‘arrival of the sacred tree’ fragment. 1305 copy, Tokyo National Museum. Shotoku Taishi e-den [ 聖徳太子絵伝 ]. Illustrated Biography of Prince Shotoku (1305) // Online Cultural Heritage Website. URL: https://bunka.nii.ac.jp/ heritag-es/detail/147157/2 (accessed 07.07.2020)

Рис. 1. Панель № 4 «Иллюстрированная биография принца Сётоку». Фрагмент «Прибытие священного дерева», копия 1305 г., Национальный музей Токио

A piece of ranjatai wood (156 cm long, 11.6 kg in weight, measuring 42.5 cm at its widest part) is recognized as an important national treasure. It continues to have a high reputation, embodying in a certain sense the imperial power [Shoso-in, 1994. P. 40]. There are many extraordinary stories associated with this piece of wood. According to legend, it was transported from China to Empress Komyo in 756 to the Todaiji Temple. As a result, it ended up with other treasures of Emperor Shomu in the special Shoso-in storehouse to perpetuate his memory and is kept there to this day [Peace and Harmony, 2011. P. 112].

As for the initial uses of aromatic raw materials, at the beginning of the Nara era (710–784), along with the spread and consolidation of Buddhism, a large amount of aromatic wood was brought from mainland China to Japan. At that time, it was widely used in Buddhist memorial services (it was burned in front of a sign with the name of the deceased). Since this kind of wood was not known to contain wood bugs, it was also used to manufacture cases for storing sutra scrolls and writing brushes. In addition, this wood was also often used to make jewellery boxes, game boards, handles and sword sheaths 7.

Since the Heian era (794–1185), pieces of aromatic wood burning on a Buddhist altar were called 名香 myougou (‘aromatic trees with a fine smell’), and this term was assigned the meaning of ‘a scent presented as a gift to Buddha’. During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), the pronunciation of this word changed – it began to sound similar to meikou (short for 名物の香 meibutsu-no kou – ‘the aroma of fine items’). This name acquired the following meanings – ‘aroma of noble origin’ (由緒ある香 yuisho aru kou), ‘aroma of a wonderful fragrance’ (香気の優れた香 kouki-no sugureta kou), for wood included 8.

Aromatic aquilaria wood classifications in Japan

Specifically the Muromachi period can be credited for the beginning of classifications of 名香 meikou high-quality fragrant wood in Japan, which subsequently gained great fame.

Among the most famous is the classification of 180 types of fragrant wood, developed by military leader of the period of the Southern and Northern courts who was famous for his extravagance, Sasaki Doyo ( 佐々木道誉 , 1296–1373), as well as the classification of ten types of fragrant wood, compiled by tea master Yamanoue Soji ( 山上宗二 , 1544–1590). There were other lists of fragrant wood, including 66 types ( 六十六種名香 ), 120 types ( 百二十種名香 ), 130 types ( 百三十種名香 ) and even 200 types ( 二百種名香 ) [Jinbo Hiroyuki, 2003. P. 446].

By order of the 8th shogun of the Muromachi period, Ashikaga Yoshimasa ( 足利義政 , 1436– 1490), a famous patron of the arts, the head of the main schools of the ‘aroma path’ 香道 koudou – Shino Soushin ( 志野宗信 , 1443–1522), founder of the Shino-ryuu school ( 志野流 ), and Sanjonishi Sanetaka ( 三条西実隆 , 1455–1537), founder of the Oie-ryuu school ( 御家流 ), were given the task of compiling a list of the best wood aromas, taking into account the specifics of the scent and place of growth, resulting in the ‘61 kinds of aromatic wood’ list ( 六十一種名香 rokujuu isshu meikou ), which to this day is still considered to be the set standard in Japanese fragrance art 9.

It is worth mentioning that the list of 61 types of aromatic woods starts with two types of agar trees that have special names, named after the temples where the fragments of wood were originally located – 法隆寺 Horyuji (or 太子 Taishi) 10 and 東大寺 Todaiji (or 蘭奢待 Ranjatai).

List of 61 types of aromatic wood

法隆寺・東大寺(蘭奢待)・逍遥・三芳野・紅塵・枯木・中川・法華経・花橘・八 橋・園城寺・似・不二の煙・菖蒲・般若・鷓鴣斑・青梅・楊貴妃・飛梅・種島・澪標・ 月・竜田・紅葉の賀・斜月・白梅・千鳥・法華・臘梅・八重垣・花の宴・花の雪・名月・ 賀・蘭子・卓・橘・花散里・丹霞・花形見・上薫・須磨・明石・十五夜・隣家・夕しぐ れ・手枕・有明・雲井・紅・泊瀬・寒梅・二葉・早梅・霜夜・七夕・寝覚・東雲・薄紅・ 薄雲・上馬

Horyuji, Тоdaiji (Ranjiatai), Shoyo (Stroll), Miyoshino, Kojin (Red Dust), Dead Koboku Tree, River Nakagawa, Hokekyo (Lotus Sutra), Hana-tachibana (Blooming Citrus) 11, Yatsuhashi (Eightpiece Bridge) 12, Onjoji Temple 13, Nitari (Similarity), Fuji-no kemuri (Smoke over Fuji), Ayame (Iris), Hannya (Prajna), Shakoban (Spots of Pearl of Black Francolin) 14, Aoume (Green Plum),

Yang Guifei, Tobiume 15 (Flying Plum), Tane-ga shima, Miotsukushi 16, Tsuki (Moon), Tatsuta 17, Momiji-no ga 18, Shagetsu (Moon Bowing to the West), Hakubai (White Plum), Chidori (Sandpiper), Hokke (Flower of the Law), Robai (Winter Blossom) 19, Yaegaki (Eight-Layer Fence) 20, Hana-no en 21, Hana-no yuki (Flower Snow) 22, Meigetsu (Full Moon), Gа (Celebration) 23, Ransu (Orchid Child), Joku (Near the Altar) 24, Tachibana (Citrus), Hana-chirusato 25, Tanka (Red Clouds, pierced by sun rays), Hana-gatami (Flower Basket) 26, Uwadaki (Fume for the Top Dress), Suma, Akashi 27, Jugoya (Fifteenth Night), Rinka (House Next Door) 28, Yushigure (Evening Rain), Tamakura (Hand pillow), Ariake (Pre-Dawn Moon), Kumoi (Cloud Abode), Kurenai (Scarlet), Hatsuse, Kanbai (Winter Plum), Futaba (Two First Leaves), Sobai (Early Plum), Shimoyo (Cold Night) 29, Tanabata (Seventh Night), Nezame (Awakening), Shinonome (Dawn Clouds), Usukurenai (Pink) 30, Usu-kumo 31, Noboriuma (Beautiful Horse) 32.

It must be mentioned that all these types of aromas belong to different varieties of agar wood 沈 香 jinkou , the features of which differ significantly from each other depending on the place of growth and the type of forming. This list was compiled taking into account the specifics of different types of agar wood.

In terms of the features of this list, in addition to the first names associated with the main and oldest Buddhist temples of Nara, the rest of the names are mostly the names of seasonal phenomena, ceremonies and observances of the Chinese calendar (for example, the autumn festival of the clear moon 十五夜 jugoya (‘Fifteenth Night’), the celebration of Bootes and Weaver 七夕 tanabata and others). In addition, a number of agar wood varieties are named in association with poetic and figurative names of plants and trees (‘Early Plum’ 早梅 sobai ; ‘Green Plum’ 青梅 aoume 33; ‘Winter Plum’ blooming in the cold 寒梅 kanbai and others) as well as established traditional culture images (bridge with eight sections 八橋 yatsuhashi 34 in a Japanese garden; a special ‘seasonal word’ in Japanese poetry 夕時雨 yushigure ‘Evening Rain’, associated with winter, and others).

A number of names do not refer to the original images of Japanese culture and literature, but instead refer to well-known Buddhist works (for example, the ‘Lotus Sutra’ 法華経 Hokekyo ), widely used Buddhist concepts such as 般若 hannya (‘wisdom’, ‘insight’, Sanskrit: Prajñā ) and 紅塵 kojin (literally ‘Red Dust’ meaning ‘secular vanity’), or even famous characters such as the beautiful Yang Guifei 楊貴妃 – the beloved of the Chinese Emperor Xuan-zong (685–762).

However, most of the names of aromatic wood types in the list are associated with Japanese classical literature. Apart from references to well-known theatrical dramas (for example, Zeami’s ‘Flower Basket’ play 花形見 Hanagatami ), there are many examples from a famous work of the Heian period – ‘The Tale of Genji’, written at the turn of the 10th –11th centuries by Murasaki Shikibu. Generally, these are chapter titles from the famous work: ‘Celebration of the Scarlet Leaves’ 紅葉の賀 (Ch. 7); ‘Celebration of Flowers’ 花の宴 (Ch. 8); ‘Garden Where the Flowers Fall’ 花散里 (Ch. 11); ‘Suma’ 須磨 (Ch. 12); ‘Akashi’ 明石 (Ch. 13); ‘Melting Cloud’ 薄雲 (Ch. 19) and others.

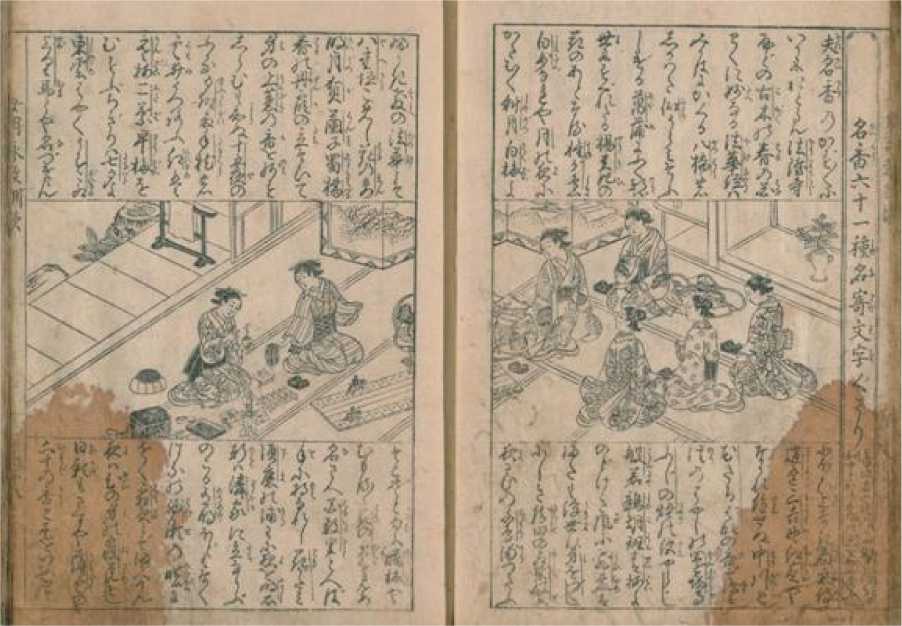

It must be noted that these elegant names, evoking an entire train of literary and artistic allusions, are very difficult to remember, being lined up one after another in the list. As a result of this, it seems that in the second half of the Edo period (at the end of the 18th century), an unknown author created a rhythmically organized poem of seven and five syllables, which eventually became known as ‘A Chain of Word-Names for 61 Types of Fragrances’ ( 名香六十一種名寄文字鎖 Meikou rokujyuu ishhuu nayose moji kusari ) 35. Subsequently, it was included in publications for women's education. Among the earliest are editions such as ‘Educational songs for chanting recitations for women’ ( 女朗詠教訓歌 Jorouei kyoukun-uta , 1753) and ‘Writings for women's reading’ ( 女用続 文章 Joyou yomi bunsho , 1787) and some others (Fig. 2).

Based on the classifications of 61 types of aromatic wood compiled at the beginning of the 16th century, another system was finally formed by the end of the 17th century by two luminaries of koudou art – Sanjonishi Sanetaka and Shino Soshin, – called ‘Six Countries – Five Flavours’ ( 六国 五味 rikkoku-gomi ), which united the best agar wood incents from India and tropical Asia with various types of flavours: 甘 kan (sweet), 酸 san (sour), 辛 shin (spiced), 鹹 kan (salty), 苦 ku (bitter). Considering the places where aromatic plants grow, six varieties of agar wood were identified by the names of six countries: 伽羅 kyara wood with a spiced flavour and pungent smell (the best kinds from India, Vietnam); 羅国 rakoku sweet wood (Siam, Myanmar); 真那伽 manaka wood without any pronounced smell (Malacca, Malaysia); 寸聞多羅 sumotara bitter-salty, slightly sweet wood (Sumatra); 真南蛮 manaban sour-bitter wood (Malabar region on the eastern coast of South India) and the 佐曾羅 sasora wood with a cold and salty flavour (India and Indonesia) [Voytishek, 2011. P. 189–190; Voytishek, 2019. P. 70–71].

In accordance with this system, the highest quality kyara wood contained all five kinds of smells, which is why it was often called 五味立 gomi-tatsu (‘containing five flavours’). The famous 蘭奢 待 ranjatai wood from the Todaiji Temple was believed to be of this type (Fig. 3).

As for the classification of 61 types of fragrant agar wood, it was reconsidered in the Edo period. Based on the already existing classification and in accordance with the ‘Six Countries – Five Flavours’ system, first of all, 11 varieties of wood were distinguished (six types of 伽羅 kyara wood native to India, three types of 羅国 rakoku wood native to Siam (modern-day Thailand), two types of 真那伽 manaka wood native to Malacca). Among the 50 remaining agar wood types, 41 types were identified as 伽羅 kyara , six types as 羅国 rakoku , nine types as 真那蛮 manaban native to the east coast of India, and five types as 真那伽 manaka native to Malacca 36.

Fig. 2. Onna rouei kyoukunka [ 女朗詠教訓歌 ]. Educational songs for chanting recitations for women. Kyoto, Uemura Toemon, 1753. 1 note // Electron. Collection of the National Parliamentary Library. URL: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/ in-fo:ndljp/pid/2533881 (accessed 07.07.2020)

Рис. 2. Онна ро:эй кё:кунка [ 女朗詠教訓歌 ]. Поучительные песни для декламации нараспев женщинами. Киото: Уэмура Тоэмон, 1753. 1 тетр. // Электрон. коллекция Национальной парламентской библиотеки. URL: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/2533881 (дата обращения 07.07.2020)

In addition, around the same time, two types began to be distinguished from the kyara wood – the old ( 古伽羅 ko kyara ) and new ( 新伽羅 shin kyara ). As a result of these reconsidered types, a system of seven types of aromatic wood was gradually formed, which is still considered one of the most optimal and harmonious classifications. Currently, it is used by many experts in assessing the quality of aromatic wood [Peace and Harmony, 2011. p. 46–48; 112–113].

The above classification was founded on the principle of reliance on taste and olfactory receptors. Indeed, in order to determine an aroma type, fragrant wood is heated and the quality of the smell emanating from it is assessed (‘sweet’, ‘sour’, ‘salty’, ‘bitter’ or ‘spiced’). According to the apt observation of Iwasaki Yoko of Doshisha University (Kyoto, Japan), labeling aromas with flavour and smell reveals another problem: smell is an extremely erratic sense. In addition, the human nose can become quickly accustomed to scents, which results in a short-lived ability to assess aromas. Consequently, the wisdom of medieval masters was contained within the ability to label scents with flavours, so that, due to such an encoding, specific aromas could be extracted from memory 37.

Fig. 3. Collage. From right to left: Wood of the famous agar tree 黄熟香 oujuku-kou ( 蘭奢待 ranjatai ) from the Shoso-in National Treasury at Toudaiji Temple (Nara, Japan) (Shoso-in, 1994. p. 40); Aromatic wood ‘Six Countries’: rakoku , kyara, sumotara, manaka, manaban, sasora (length 42.5 cm) (Koudougu, 2006. Р. 80). On the top: Aromatic wood cutting tool sets (Koudougu, 2006. Р. 149). (Collage by I. A. Axenov)

Рис. 3. Коллаж. Справа налево: Знаменитая древесина агарового дерева 黄熟香 о:дзюку-ко: ( 蘭奢待 рандзятай ) из национальной сокровищницы Сё:соин при храме То:дайдзи (Нара, Япония) (Сё:со:ин, 1994. С. 40); Ароматическая древесина «из шести стран»: ракоку , кяра , сумотара , манака , манабан, сасора (длиной 42,5 см) (Ко:до:гу, 2006. С. 80). Наверху: Наборы инструментов для разрезания ароматической древесины (Ко:до:гу, 2006. С. 149). (Коллаж – И. А. Аксёнов)

Currently in Japan, aquilaria wood continues to be highly valued. In addition to its use in medicine, perfumery and cosmetology, agarwood has found its use in the art of 香道 koudou (‘way of fragrance’), presenting the opportunity to enjoy incense in a refined atmosphere, appreciate its importance in religious ceremonies and the arts sphere. The Japanese are convinced that this art contributes to the purification of consciousness, awakens humanity and displays temperament. By ‘listening to incense’ ( 聞香 monkou ) one can emphasize the beauty and uniqueness of each season [Morita Kiyoko, 2015. P. 13–15].

Ever since a piece of aromatic wood miraculously made its way into Japan, incense has become a part of everyday life of commoners, samurai, aristocrats, and wealthy merchants, eventually becoming a part of popular culture. Products made from aromatic wood entered the sphere of decorative applied arts long ago: it is used to carve out sculptures of characters from the Buddhist pantheon, figurines, vessels, jeweler boxes, fans, stands, and various game boards. A separate form of the Japanese art of incense was the manufacture of various and richly decorated tools for splitting and sawing bars of aromatic wood. The great importance of incense and various aromatic substances in the history of Japanese culture is underscored by the presence of a significant number of metaphors, idiomatic expressions and proverbs associated with the fragrant wood of aquilaria and sandalwood [Peace and Harmony, 2011. P. 113; Kan’yo kotowaza jiten, 1988; Kotowaza 15000 jiten, 1989; Nichiei hikaku kotowaza jiten, 1981].

Conclusion

Based on the analysis of Japanese written and artistic sources, as well as field research of the authors of the article, the main classifications of the aromatic wood species of the agar tree (aquilaria) which have played a large role in the culture of Japan for one and a half millennia, were considered. Some of these classifications are still used by authoritative experts when assessing the quality of wood and wood products.

The uniqueness of these classifications lies in their scientific significance, which is confirmed by the mass of historical and written sources, and also determined by their role in culture, literature, religious and everyday practices of the entire region. Attention is drawn to the undoubted discovery of medieval Japanese masters of methods of encoding one or another aroma of fragrant wood, associated not only with the specific characteristics of flavours and places of growth of aromatic trees, but also with the figurative-symbolic meaning of each name, the more notable ones of which are Buddhist and worldview concepts, philosophical categories, historical precedents, famous characters from the history of Japan and China, elements of the calendar year and festive rituals, natural phenomena, poetic and literary images, myths and legends.

Analysis of various types of aromatic wood invariably leads to the topic of formation and development of trade and economic ties in East, Southeast Asia and tropical regions of South Asia, to the study of the role of trade intermediaries from the Middle East and Central Asia (this is also indicated by archaeological finds from sunken ships, as well as burnt seals and inscriptions on pieces of wood in Sogdian, Persian and Pahlavi languages). Perhaps the discovery and study of new sources and artifacts in these languages in the future will make it possible to more accurately determine the routes of the merchant ships and fully appreciate the cultural finds. In addition, the study of the phenomenon of aromatic wood seems promising from the point of view of the existence of a specific category of 唐物 karamono goods (‘items from China’), on the supply of which the habits and social status of the aristocracy, clergy and high military leaders largely depended.

The importance of aromatic culture in Japan, which has developed almost 1,500 years ago since the discovery of the aromatic wood bar off the coast of Awaji island is truly immense. As in many countries of East and Southeast Asia, it is not merely limited to medical, sanitary and hygienic functions, religious and cult practices, or everyday needs. However, it was only in Japan that the use of aromatic raw materials rose to become a true form of art. Having united with the ideological and worldview foundations of Buddhism and adopting the principles of aristocratic and later samurai ideology, the use of incense, enriched with various methods, techniques and accessories, over time transformed not only into traditional art, but also turned into a certain symbol of national culture, largely based on the awareness of the value of the present moment, the transience of life and the ephemerality of everything.

An unusually reverent and careful attitude to different types of aromatic substances, as well as to all the circumstances accompanying the history of their emergence, the peculiarities of use and evaluation, is one of the stable constants of traditional Japanese culture. There are many examples of this from ancient and modern Japanese history, one of which is the cultural phenomenon of fragrant wood, the boundaries of which to this day have never been fully defined to its fullest extent.

Ishigami Eiichi . Ho: ryu: ji garan engi narabini ryu: ki shizai cho: shoshahon-no denrai [ 石上英一。 法隆寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳諸写本の伝来 ]. An introduction to the manuscript docu-ments“Descriptions of the History and Property of the Horyuji Temple”. Bulletin of the Institute of Historiography , 1976, no. 10, p. 1 - 10. (in Jap.)

Jinbo Hiroyuki . Koudou-no rekishi jiten [ 神保博行。香道の歴史事典 ]. In: Encyclopedia of the history of art of incense. Tokyo, Kashiwa-shobo, 2003, 454 p. (in Jap.)

Kan’yo kotowaza jiten [ 慣用ことわざ辞典 ]. Learning Dictionary of Proverbs. Tokyo, Shogakukan, 1988, 424 p. (in Jap.)

Kojiki - Records of Ancient Matters. Transl., comment. E. M. Pinus. St. Petersburg, SHAR, 1993, 320 p. (in Russ.)

Kojiki [ 古 事 記 ]. Records of Ancient Matters. Transl. to modern Jap. Fukunaga Takehiko. Tokyo, Kadokawa Shouten, 2014, 445 p. (in Jap.)

Kotowaza 15000 jiten [ ことわざ 15000 辞典 ]. Dictionary of 15,000 proverbs. By Yamada Mitsuji.

Osaka, Musashi shobo, 1989, 854 p. (in Jap.)

Koudougu [ 香道具 ]. Incense art accessories. By Arakawa Hirokazu. Kyoto, Tankosha, 2006, 255 p.

(in Jap.)

Morita Kiyoko . The Book of Incense. Enjoying the traditional art of Japanese scents. New York, Kodansha, 2015, 134 p.

Nichiei hikaku kotowaza jiten [ 日英比較ことわざ辞典。監修山本忠尚 ]. Japanese-English Proverbs Comparative Dictionary. By Yamamoto Tadahisa. Tokyo, Sogensha, 1981, 394 p. (in Jap.)

Nihon shoki . Annaly Yaponii [Chronicles of Japan]. Transl. by L. M. Ermakova and A. N. Mesheryakov. St. Petersburg, Giperion, 1997, vol. 2, 427 p. (in Russ.)

Ota Kiyoshi . Kaori to chanoyu [ 太田清史。香と茶の湯 ]. Incense and tea ceremony. Kyoto, Tankousha, 2001, 190 p. (in Jap.)

Peace and Harmony [ 祥和。中國香港沉香珍藏展 ]. The Divine Spectra of China’s Fragrant Harbour. A Collection of 108 Aloes of Sacred Scripture and Related Artifacts. Ed. by P. Kan. Hong Kong, 2011, 289 p. (in Chin. and Eng.)

Shoso-in [ 正倉院 ]. Shoso-in National Repository. Nara, Shoso-in jimusho kanshuu, 1994, 79 p.

(in Jap.)

Voytishek E. E. Igrovye traditsii v dukhovnoi kul'ture stran Vostochnoi Azii (Kitai, Koreya, Yaponiya). Game tradition in the culture of East Asia countries (China, Korea, Japan). Novosibirsk, NSU Publ., 2011, 312 p., 44 p. with ill. (in Russ.)

Voytishek E. E. The “Imperial Fragrance” of East Asian Culture: types, properties and features of the agarwood tree. Vestnik NSU. Series: History and Philology , 2019, vol. 18, no. 4: Oriental Studies, p. 61–74. (in Russ.)

Morita Kiyoko . The Book of Incense. Enjoying the traditional art of Japanese scents. New York, Kodansha, 2015. 134 p.

Нитиэй хикаку котовадза дзитэн [ 日英比較ことわざ辞典。監修山本忠尚 ]. Японоанглийский сравнительный словарь пословиц / Под ред. Ямамото Тадахиса. Токио: Со-гэнся, 1981. 394 с.

Нихон Сёки . Анналы Японии / Пер. со старояп. Л. М. Ермаковой и А. Н. Мещерякова. СПб.: Гиперион, 1997. Т. 2. 427 с.

Ота Киёси . Каори то тя-но ю [ 太田清史。香と茶の湯 ]. Благовония и чайная церемония. Киото: Танко:ся, 2001. 190 с. (на яп. яз.)

Сё:со:ин [ 正倉院 ]. Национальное хранилище Сё:со:ин. Нара: Сё:со:ин дзимусё кансю:. 1994. 79 с. (на яп. яз.)

Peace and Harmony [ 祥和。中國香港沉香珍藏展 ]. The Divine Spectra of China’s Fragrant Harbour. A Collection of 108 Aloes of Sacred Scripture and Related Artifacts / Ed. by P. Kan. Hong Kong, 2011. 289 р. (на кит. и англ. яз.)

Материал поступил в редколлегию Received 20.07.2020

Список литературы The strength of the fragrance for one and a half thousand years: agarwood in the Japanese art of incense

- Ise monogatari (‘Literature artifacts' series). Transl., comment. by N. I. Konrad. Moscow, Nauka, 1979, p. 287.

- Ishigami Eiichi. Ho: ryu: ji garan engi narabini ryu: ki shizai cho: shoshahon-no denrai [石上英一。法隆寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳諸写本の伝来]. An introduction to the manuscript documents"Descriptions of the History and Property of the Horyuji Temple". Bulletin of the Insti-tute of Historiography, 1976, no. 10, p. 1-10. (in Jap.)

- Jinbo Hiroyuki. Koudou-no rekishi jiten [神保博行。香道の歴史事典]. In: Encyclopedia of the history of art of incense. Tokyo, Kashiwa-shobo, 2003, 454 p. (in Jap.)

- Kan'yo kotowaza jiten [慣用ことわざ辞典]. Learning Dictionary of Proverbs. Tokyo, Shogakukan, 1988, 424 p. (in Jap.)

- Kojiki. Records of Ancient Matters. Transl., comment. E. M. Pinus. St. Petersburg, SHAR, 1993, 320 p. (in Russ.)