The study of permanent migration of economically depressed regions

Автор: Chernyshev Konstantin Anatolevich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Young researchers

Статья в выпуске: 4 (52) т.10, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Russia's development in the post-Soviet period is characterized by enhanced interregional socio-economic disparities, emergence of different kinds of troubled territories including depressed areas. The group of depressed regions includes ten constituent entities of the Russian Federation where economic recession is accompanied by reduction in the number of residents and the population outflow as a result of permanent migration. The purpose for this research is to identify the specific features of migration processes in economically depressed regions and elaborate proposals to optimize migration policy. The information base of the research is represented by official data of Rosstat. The article analyzes the processes of permanent migration in depressed areas, proposes periodization of migration process in the post-Soviet period and defines the reasons for the occurred changes. The author identifies net migration indicators and population decline in depressed Russian regions by flows of permanent migration: interregional and international between neighboring and distant countries...

Russia, economically depressed areas, permanent migration, migration outflow, migration intensity index, post-soviet period

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223964

IDR: 147223964 | УДК: 314.7 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2017.4.52.15

Текст научной статьи The study of permanent migration of economically depressed regions

Introduction. The development of Russia in the post-Soviet period was characterized by significant transformational processes caused by rapid transition to market economy and its subsequent development. One of the consequence of radical transformations which affected almost all spheres of the society was the strengthening of interregional socioeconomic differentiation, the emergence of different kinds of problematic regions.

One of the types of such regions is depressed regions which, during the process of transition from planned to market economy were characterized by relatively low economic performance, although these regions was developed in the past leading in a number of industries in the country. The main criterion of depression is usually production decline especially in industry [5; 15]. Often entire constituent entities have clear signs of depression.

The emergence of centers of regional economic depression in the post-Soviet period is due to issues of regions’ adaptation to new economic conditions and declining competitiveness of “old” industries. Negative changes in regional economy determined the social consequences as “total territorial depression in the Russian version always has an extremely powerful social “lopsidedness”: the destruction of economic potential is followed by a rapid breakdown of social potential, with these processes driving each other” [4, pp. 252–253]. Production decline was accompanied by rising unemployment, declining living standards, spread of negative social phenomena, as well as various demographic issues (increasing mortality, reducing fertility, migration loss), etc.

Some authors propose that negative net migration is considered as one of the criteria of depression [7]. From our point of view, the use of net migration loss (as well as population’s reproduction record) does not fully reflect the nature of regional depression as a primarily economic phenomenon. The level and pace of regional development influence migration processes [20]; however, out-migration may be explained by long-term negative changes in the economy of specific regions and the influence of other factors (environment, local conflicts, proximity of attractive regions, etc.). However, the extent, course and results of migration processes are important indicators of regions’ socioeconomic issues, as informative as GRP volume and performance, investment activity, etc.

Identification of depressed regions. Researchers propose different criteria to classify a certain area as depressed. The most requested indicators for allocating depressed regions are a decline in industrial production, level of unemployment, and GRP per capita. In order to determine the list of depressed constituent entities of the Russian Federation and further study their migration situation we use the following criteria.

-

1. Decline in industrial production. The criterion reflects the idea of depressed regions as industrially developed but having experienced production decline. From our point of view, a decline in industrial production to a 70% level compared to 1991 is significant.

-

2. GRP per capita is significantly below the national average. The process of industrial decline during the Soviet period was not always accompanied by a decrease in GRP per capita. It refers to regions where the decline in industrial production was combined with the development of other economic sectors

-

3. Unemployment rate is above the national average. Production decline in industrial regions is accompanied by rising unemployment. Since last few years were characterized by crisis phenomena in the economy accompanied by changes on the labor market, the unemployment rate was calculated on average for 2008–2015

-

4. Industrial production per capita. The threshold value was taken to be equal more than 30% compared to the average level of industrial production per capita in Russia. This indicator is necessary to separate the regions without the industrial focus of the economy neither in the past, nor now which traditionally belong to underdeveloped regions from the list of all constituent entities of the Russian Federation (republics of the North Caucasus, Altai, Kalmykia, the Jewish Autonomous oblast).

(primarily Moscow, Saint Petersburg) or occurred on the background of significant population reduction (Kamchatka Krai). It is incorrect to include in the list of depressed regions a region with GRP per capita equaling or exceeding than the national average. The category of depressed regions includes constituent entities with GDP per capita less than 70% of the national average.

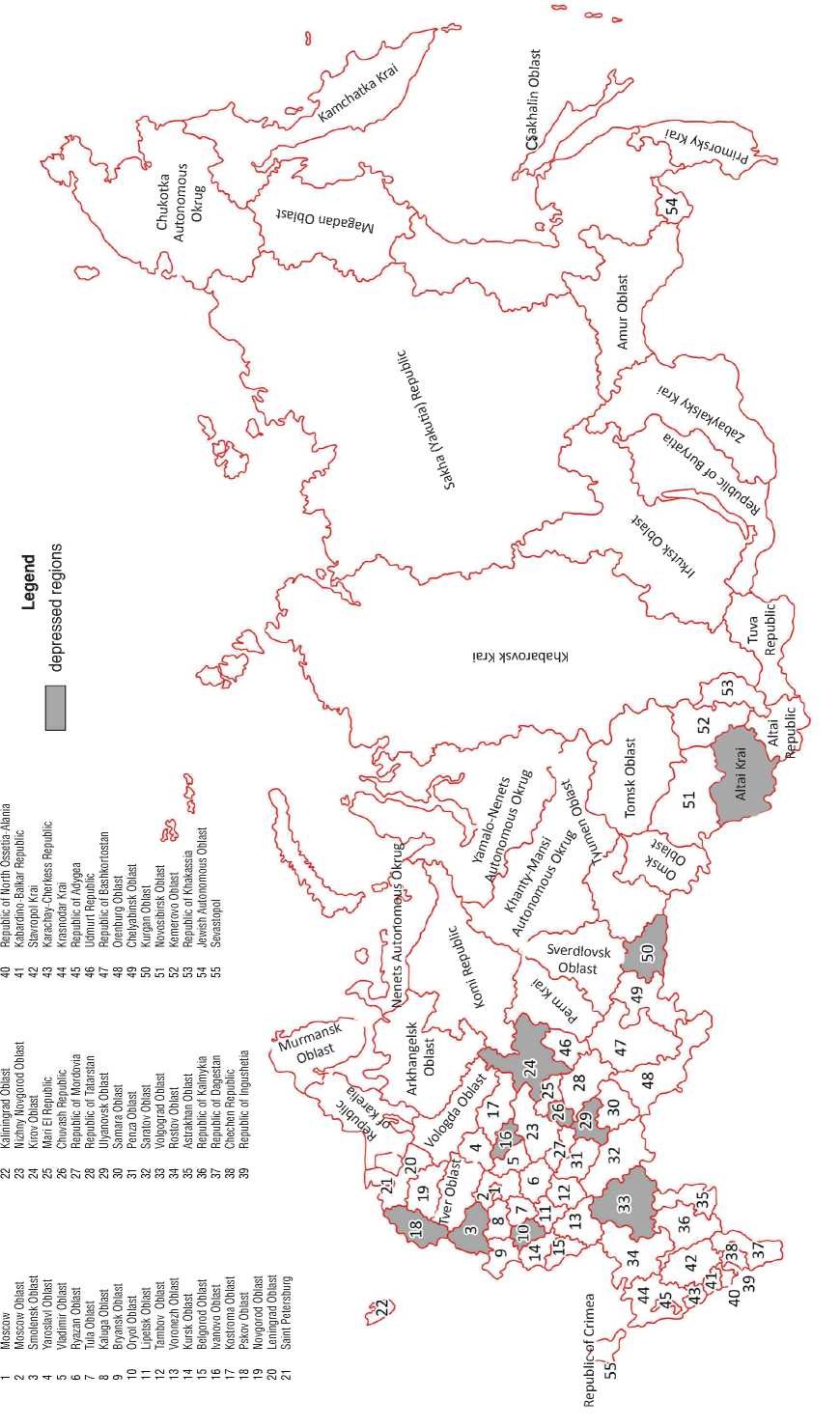

According to the proposed methodology, the category of depressed regions in 2011– 2015 includes ten constituent entities of the Russian Federation ( Tab. 1 ). Depressed regions do not form large adjacent areas

Table 1. Economic and social status of depressed Russian regions*

|

Depressed region |

Industrial production in 2015 compared to 1991 (in comparable prices), % |

Industrial production per capita in 2015, in current prices |

GRP per capita in 2015, in current prices |

Average unemployment rate for 2008–2015 |

Population |

|||||

|

thousand rubles |

in % to the national average |

thousand rubles |

in % to the national average |

in the region, % |

how much more than the national average, % |

in 1991, thousand people |

in 2015, thousand people |

2015 to 1991, % |

||

|

Ivanovo Oblast |

33.9 |

114.3 |

34.1 |

165.5 |

37.2 |

6.44 |

0.15 |

1293.9 |

1033.4 |

79.9 |

|

Oryol Oblast |

55.3 |

147.4 |

44.0 |

269.9 |

60.6 |

6.69 |

0.40 |

896.7 |

762.5 |

85.0 |

|

Smolensk Oblast |

67.4 |

228.5 |

68.1 |

267.3 |

60.1 |

6.50 |

0.21 |

1158.1 |

961.7 |

83.0 |

|

Pskov Oblast |

65.8 |

133.9 |

39.9 |

204.8 |

46.0 |

7.95 |

1.66 |

843.5 |

648.7 |

76.9 |

|

Volgograd Oblast |

59.5 |

285.0 |

85.0 |

288.2 |

64.7 |

7.48 |

1.19 |

2631.0 |

2551.7 |

97.0 |

|

Сhuvash Republic |

56.7 |

135.8 |

40.5 |

202.4 |

45.5 |

7.31 |

1.02 |

1338.5 |

1237.4 |

92.4 |

|

Kirov Oblast |

53.2 |

165.9 |

49.5 |

212.5 |

47.8 |

7.28 |

0.99 |

1650.3 |

1300.9 |

78.8 |

|

Ulyanovsk Oblast |

57.6 |

209.3 |

62.4 |

239.2 |

53.7 |

6.59 |

0.30 |

1416.1 |

1260.1 |

89.0 |

|

Kurgan Oblast |

54.6 |

123.1 |

36.7 |

207.6 |

46.6 |

9.41 |

3.12 |

1106.1 |

865.9 |

78.3 |

|

Altai Krai |

64.2 |

122.1 |

36.4 |

206.7 |

46.4 |

8.46 |

2.17 |

2647.1 |

2380.8 |

89.9 |

* Calculated according to: Russian regions. Socio-economic indicators. 2016: statistics book. Moscow: Rosstat, 2016. 1326 p.; Federal State Statistics Service. Available at: ; ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/ru/statistics/enterprise/industrial/#

throughout the country being mainly situated in the European part of Russia. The industry in these regions was unable to shift towards market economy unharmed due to objective reasons: predominance of “old” industries, entry to the market of the country’s competitors from abroad, reducing state demand, broken economic links with former Soviet republics. This was combined with absence in depressed Russian regions of explicit factors able to make the transition less harmful (export-oriented resource industries, capital status, etc.). The selected depressed regions are concentrated within the Volga and Central (3), Southern, Northwestern, Ural, Siberian (1) federal districts ( Fig. 1 ).

Migration processes have their own specific features in depressed regions and require detailed consideration. There is experience of studying migration processes in the group of regions selected by similar issues of socio-economic development: border [8], earlier developed [9], oil and gas [13] etc. The consequence of the economic decline in depressed regions was population outflow resulting in permanent migration. The study of migration in depressed regions was carried out only at the level of some constituent entities [1; 2; 16]. A number of studies which review population issues associate the phenomenon of regional depression with different performance of the processes of

reproduction or migration [6], for which the use the concept of “regions, depressed relative to net migration”. There are also examples of regional demographic studies where subsidized regions are considered depressed [3].

Migration flows and migration ties in depressed regions. Sources of information on permanent migration in depressed regions were data from the current record presented in statistics books and recalculated taking into account population census in depressed constituent entities. During the post-Soviet period, there were noticeable fluctuations in the recorded amounts of domestic and international permanent migration due to a change in migration flow and repeated revision of the migration registration procedure. This made useless the performance analysis of absolute values and indicators of migration intensity in regions [12]; however our research results have not been fundamentally affected since the change were related to all Russian regions and migration rates were calculated in general for a longterm period.

Population loss in depressed regions over the post-Soviet period was significant. During 1992–2015, the population of depressed Russian regions decreased from 15.0 to 13.0 million people despite net migration at the end of the 20th century. Natural population decline played a major role in the population decline during the post-Soviet period.

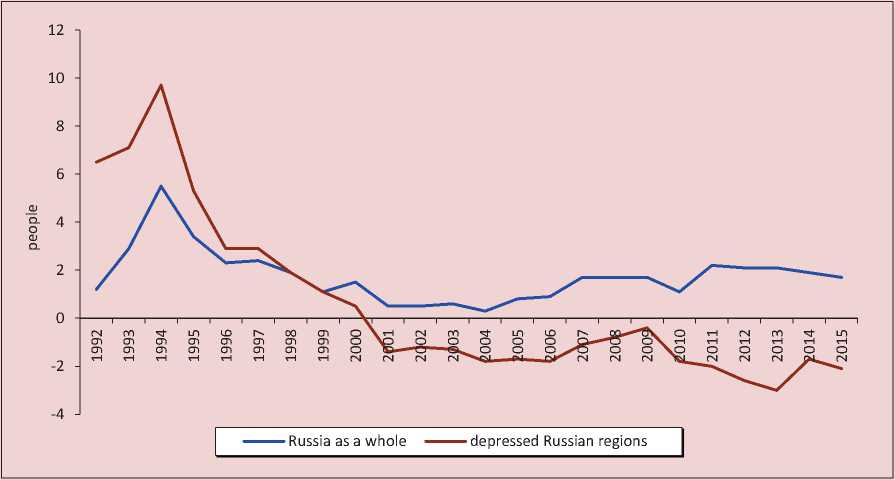

Performance of migration processes in depressed constituent entities in the postSoviet period was uneven. In the 1990-s, depressed regions had higher migration rates than the national average ( Fig. 2 ). During this period, most regions in European Russia experienced an unprecedented migration growth caused by forced migration from unstable regions of the former USSR, migration from the North. We believe that a significant part of migrants arriving in depressive subjects of the Russian Federation during the 1990-s were those who for decades had been leaving these regions, as well as their relatives, i.e., migration was largely return in nature. This is possible when people keep in touch with the region of departure and local residents who would help them settle. Such resettlement could occur in least economically prosperous regions. Thus, amid stress migration depressed regions which have been population donors for many years could count rely on migrant influx.

By the early 2000s, the migration potential of the Russian population was largely exhausted. There was a gradual transformation of politically motivated international migration into economically motivated migration of compatriots and representatives of the titular nations of the CIS [11]. However, depressive Russian regions having no distinct pull factors began to lose the competition for main migrant flows which as a result were channeled to other Russian

Figure 2. Migration gain (loss) per 1000 people in depressed Russian regions during the post-Soviet period*

* Compiled from: Rosstat unified interdepartmental information-statistics system. Available at: ; Russian statistics yearbook: statistical compilation. Russian State Statistical Committee. Moscow: Logos, 1996.

regions. In addition, the economic recovery in Russia in the 2000-s was accompanied by an increase in population outflow from depressed to more migration-attractive regions. Migration loss in depressed Russian regions in internal migration is not compensated by the inflow of migrants from neighboring countries. In the Smolensk Oblast, migration loss became apparent in 1999, in the whole group of regions of this type – since 2001. Since that time, the group of depressed regions annually loses population as a result of permanent migration, necessitating a more detailed consideration of migration processes in 2001–2015. During this period, the population loss in depressed regions as a result of migration, according to current records, amounted to 339.3 thousand people. Net migration of the population in depressed regions formed as a result of interaction with other Russian regions and near and far-abroad countries.

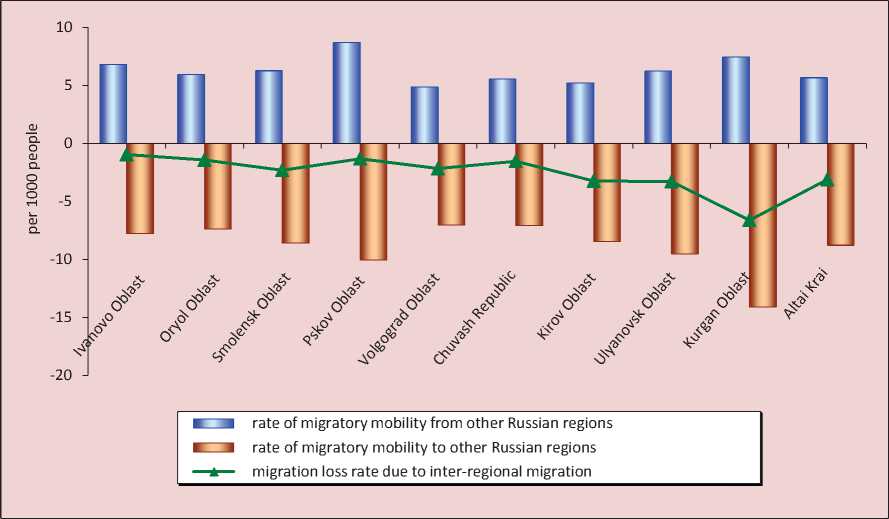

The comparison of migration and regions’ population helps allocate Russian regions with the highest intensity of different migration flows during 2001–2015. The intensity of migratory departure in the group of depressed regions to other Russian regions is higher than the national average, although it significantly differs by region. In turn, almost all the regions under review are characterized by relatively low intensity of interregional migration by arrival. The exception is the Pskov Oblast where the intensity of arrival from other Russian regions is slightly higher than the national average. The lowest rate of migration loss as a result of interaction with other regions is registered in the Ivanovo, Pskov, Oryol oblasts (Fig. 3). These Russian regions are located near metropolitan areas – the main centers of migrant attraction. Here constant migration to Moscow and Saint

Petersburg may be partially replaced with temporary forms [17]. The most significant population loss as a result of migration to other Russia regions was in the Kurgan, Ulyanovsk, Kirov oblasts and in Altai Krai. It should be noted that the study of migration conducted on the basis of population census indicate the under-record of migration from depressed regions [19].

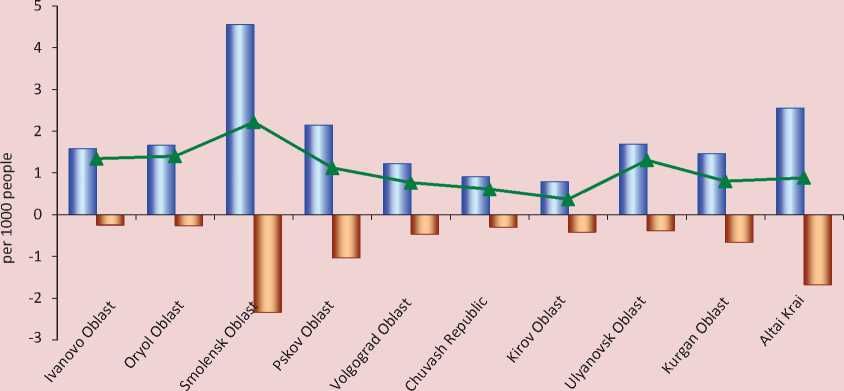

Compared to the rest of Russian regions, depressed regions demonstrate lower intensity of international migration. The lowest intensity of migration from abroad is marked in regions remote from the country’s borders

Figure 3. Inter-regional migration intensity in depressed Russian regions in 2001–2015*

* Compiled from: Population and migration of the Russian Federation in 2015: statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat, 2016; Rosstat unified interdepartmental information-statistical system. Available at:

Figure 4. International migration intensity in depressed Russian regions in 2001–2015*

■ ■ rate of migratory mobility to Russia

■ ■ rate of migratory mobility from Russia

—*— migration loss rate due to international migration

* Population and migration in the Russian Federation in 2015: statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat, 2016; Rosstat Unified Interdepartmental Information-statistical System. Available at: and major centers attractive for migrants (in the Kirov Oblast and Chuvash Republic). The population of border depressed Russian regions (Smolensk and Pskov oblasts, Altai Krai) is more involved in international migration (Fig. 4).

The highest migration growth due to permanent international migration is marked in the regions of the Central Federal district. The extent and territorial structure of migration with foreign countries also differ significantly between Russian regions as they are determined by the geographical position and traditional regional ties.

Migratory exchange of the majority of depressed Russian regions with far-abroad countries in the 2000-s was negative. The maximum population loss in the exchange with foreign countries is recorded in Altai Krai mainly due to emigration of ethnic Germans to West Germany. Some regions, primarily the Smolensk oblast, have insignificant migration gains in the exchange with far-abroad countries ( Tab. 2 ).

The main volume of migratory exchange in international migration in all depressed regions accounts for neighboring countries. As for individual Russian regions, almost

Table 2. Permanent migration flows in depressed Russian regions in 2001–2015, people*

|

Depressed region |

Number of immigrants |

Number of emigrants |

Migration gain (loss) in relation to |

||||||

|

from other regions |

from CIS and Baltic countries and Georgia |

from other countries |

to other regions |

to CIS and Baltic countries and Georgia |

to other countries |

other regions |

CIS and Baltic countries and Georgia |

other countries |

|

|

Ivanovo Oblast |

112 755 |

25 164 |

1 118 |

128 766 |

2 862 |

1 181 |

-16 011 |

22 302 |

-63 |

|

Oryol Oblast |

72 705 |

20 109 |

330 |

90 352 |

2 485 |

709 |

-17 647 |

17 624 |

-379 |

|

Smolensk Oblast |

95 911 |

62 882 |

6 846 |

131 377 |

29 668 |

6 078 |

-35 466 |

33 214 |

768 |

|

Pskov Oblast |

93 381 |

21 849 |

1 168 |

107 529 |

8 986 |

2 027 |

-14 148 |

12 863 |

-859 |

|

Volgograd Oblast |

192 109 |

46 068 |

2 464 |

278 099 |

8 468 |

9 825 |

-85 990 |

37 600 |

-7 361 |

|

Chuvash Republic |

106 453 |

14 835 |

2 633 |

136 073 |

3 112 |

2 622 |

-29 620 |

11 723 |

11 |

|

Kirov Oblast |

110 801 |

15 833 |

947 |

179 618 |

7 026 |

1 869 |

-68 817 |

8 807 |

-922 |

|

Ulyanovsk Oblast |

124 748 |

31 298 |

2 630 |

190 573 |

5 173 |

2 533 |

-65 825 |

26 125 |

97 |

|

Kurgan Oblast |

106 822 |

20 575 |

370 |

201 733 |

8 017 |

1 424 |

-94 911 |

12 558 |

-1 054 |

|

Altai Krai |

213 025 |

89 189 |

6 966 |

330 109 |

32 620 |

30 341 |

-117 084 |

56 569 |

-23 375 |

|

All depressed regions |

1 228 710 |

347 802 |

25 472 |

1 774 229 |

108 417 |

58 609 |

-545 519 |

239 385 |

-33 137 |

* Compiled from: Population and migration in the Russian Federation in 2015: statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat, 2016; Rosstat Unified Interdepartmental Information-statistical System. Available at: all of them have positive net migration in the exchange between all CIS countries (with the exception of a small migration loss in the exchange of Altai Krai with Belarus). Analysis of the available data on the territorial structure of migration during 2004– 2015 demonstrates that the main source of migration gain for the Ulyanovsk, Volgograd, Pskov and Ivanovo oblasts is Uzbekistan and it is typical for the whole Russia. For two depressed Russian regions – the Kurgan Oblast and Altai Krai – the main migration donor is Kazakhstan, the Chuvash Republic, for the Orel and Kirov oblasts – Ukraine, for the Smolensk oblast – Belarus. Since 2014,

Ukraine has been the main source of migrants for all depressed regions of the European Russia.

However, the share of migrants from selected countries in the total migration of each region does not fully reflect the real intensity of existing migratory flows as it depends on the population of the countries. For example, it is obvious that migration indices and the share of Uzbekistan in migration turnover will be higher than similar indicators for Moldova as the population of these countries varies considerably. To eliminate the influence of factors such as population of the territories and the absolute

Table 3. Countries with high IMTI values in exchange with depressed regions in 2004–2015*

|

Depressed region |

IMTI by immigration higher than 10 |

IMTI by emigration higher than 10 |

|

Ivanovo Oblast |

Armenia, Moldova |

– |

|

Oryol Oblast |

Armenia, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova |

– |

|

Smolensk Oblast |

Belarus |

Belarus |

|

Pskov Oblast |

Armenia, Moldova, Estonia |

Estonia |

|

Volgograd Oblast |

Armenia |

Armenia |

|

Chuvash Republic |

Armenia, Tajikistan |

– |

|

Kirov Oblast |

Armenia |

Armenia |

|

Ulyanovsk Oblast |

Armenia |

– |

|

Kurgan Oblast |

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic |

Kazakhstan |

|

Altai Krai |

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan |

Kazakhstan |

|

* Compiled from: Russian demographic yearbook, 2004: statistical book. Moscow: Rosstat, 2005; Russian demographic yearbook 2015 : statistical book . Moscow: Rosstat, 2015. |

||

extent of migration flows on the indicator of migration intensity is possible through the use of Indices of Migrant Ties Intensity (IMTI), which are calculated by the formulas:

IMTI em = -^ : —;

ZBij ^si’

IMTI imm = —: —,

ZPij EsP where IMTI imm – index of migrant ties intensity (by immigration); IMTI em – index of migrant ties intensity (by emigration); Bij – number of emigrants from region j to country i; Pij – number of immigrants in region j from country i; Si –average population of country j for the period; ∑Bij – total number of emigrants from depressed regions in the country under review; ∑Pij – total number of immigrants to depressed regions from the countries under review; ∑Sij – total population of the countries under review [10].

This index is applied in the studies of internal migration to assess the intensity of relations between Russian regions [14]. We calculated IMTIs for migratory interaction of depressed regions with the CIS and Baltic countries, Georgia, the United States, Germany, and Israel. High indicators by immigration and emigration (more than 10) are typical for migration exchange of depressed regions with individual CIS countries (Tab. 3), as well as the exchange of the Pskov Oblast with Latvia and Estonia. Analysis of migration relations with the CIS countries demonstrated increased IMIT values for the Chuvash Republic and Israel. In most cases, high IMTIs are explained by the geographical proximity of the regions and specific countries and a low level of socioeconomic development even compared to depressed Russian regions, as well as small population size of some foreign countries.

Main conclusions. Depressed regions are traditionally assessed as problematic compared to more successfully developing Russian regions. It is obvious that a decline in economic indicators amid depression must increase population outflow as a result of permanent migration. The main characteristic of all depressed Russian regions and at the same time one of the manifestations of economic depression is the population decline as a result of internal migration. However, during the post-Soviet period, this trend was accompanied by an increase in stress and return migration after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990-s and economic migration in the 2000-s. Being an part of the country attractive to migrants from the neighboring countries, depressed Russian regions during the post-Soviet period attracted migrants from the CIS countries. Amid reducing population in depressed Russian regions, immigrants are an important source of additional workforce for such regions, which would partially compensate, at least quantitatively, for the population decline caused by natural decline, interregional migration and emigration to developed far-abroad countries. The immigration flow to depressed regions provides significant quantitative results and slows down the process of resident population ageing reducing gender disparity. The proximity to certain countries and traditional regional ties were of decisive importance in the formation of the territorial structure of permanent migration in the 2000-s.

It is possible to identify more favorable migration situation in the regions belonging to the Central Federal district, which, in our opinion, is due to the fact that depressed Russian regions situated close to the capital region are more attractive to migrants from neighboring countries. Immigrants may consider depressed regions as transit territories for further movement in Russia. In addition, the proximity of some depressed regions to the Moscow agglomeration makes it possible to replace permanent migration with temporary forms of labor migration.

The current situation in the sphere of migration is a consequence of problems in the economic and social sphere of depressed regions. While the existing regional disparities are preserved, part of the population of depressed Russian regions will inevitably be focused on being engaged in processes of permanent or temporary migration. For this reason, activities carried out by the authorities of depressed Russian regions aimed at reducing migration outflow of the youth and people of employment age do not always produce the expected results. The implementation of the migration policy in depressed regions should be linked to measures of socio-economic development of these regions; the main goal should be to ensure the quality of life of the local population primarily by increasing wages, creating new jobs, and developing social infrastructure. At the same time, administrative mechanisms impeding temporary labor migration from depressed regions (restriction of registration and social services outside the region of residence, etc.) should be minimized. It is also necessary to consider the mechanisms of reallocating funds received by the budgets of the host regions from migrants’ labor activity in favor of the regions providing the population of depressed regions.

A relevant aspect of the migration policy for depressed regions is the regulation of immigration from neighboring countries, primarily from the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). The obvious consequences of this migration manifested in both depressed and other Russian regions include the reduction in labor costs and requirements to the working conditions. Replacement of local workers with foreign ones leads to the degradation of labor market of depressed regions where the already high unemployment rates increase migration outflow. Workers from depressed Russian regions are in competition with foreigners on the labor market of both their “own” regions and regions which are centers of attraction of temporary and permanent migrants across the country (capital, oil and gas regions, etc.); employers prefer foreign, often illegal, migrants [18].

Addressing migration and socio-economic issues of depressed Russian region is impossible without federal authorities. Certain measures to regulate migration in the regions are informational and promotional and must be supplemented with economic and administrative measures.

Список литературы The study of permanent migration of economically depressed regions

- Vasilenko P.V. Osobennosti migratsionnogo dvizheniya naseleniya Pskovskoi oblasti v postsovetskii period . Narodonaselenie , 2014, no. 2, pp. 50-57.

- Evdokimov S.I. Migratsii naseleniya kak otrazhenie ekonomicheskoi privlekatel'nosti regiona (na primere Pskovskoi oblasti) . Vestnik Baltiiskogo federal'nogo universiteta im. I. Kanta , 2010, no. 1, pp. 108-112.

- Izheikina N.M. Demograficheskie protsessy v blagopoluchnykh i depressivnykh regionakh Rossii (sravnitel'nyi analiz): avtoref. dis.. kand. ekon. nauk: 08.00.05. . Moscow: ISPI RAN, 2007. 23 p.

- Leksin V.N., Shvetsov A.N. Gosudarstvo i regiony. Teoriya i praktika gosudarstvennogo regulirovaniya territorial'nogo razvitiya . Moscow: URSS, 2007. 368 p.

- Leonov S.N. Tipologiya problemnykh regionov na osnove otsenki mezhregional'nykh sotsial'no-ekonomicheskikh i finansovykh razlichii . Izvestiya RAN. Ser. Geograficheskaya , 2005, no. 2, pp. 68-76.

- Man'shin R.V., Abidov M.Kh. Demograficheskoe razvitie Yuzhnogo federal'nogo okruga . Narodonaselenie , 2008, no. 2, pp. 81-86.

- Mil'chakov M.V. Faktory i dinamika razvitiya depressivnykh regionov i gorodov Rossii: avtoref. dis.. kand. geogr. nauk: 25.00.24 . Moscow: MGU im. M.V. Lomonosova, 2012. 25 p.

- Mikhel' E.A., Krutova O.S. Migratsionnye protsessy v zerkale transformatsii: prigranichnye regiony Rossii . Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz , 2011, no. 2, pp. 86-96.

- Mkrtchyan N.V., Karachurina L.V. Migratsionnaya situatsiya v staroosvoennykh regionakh Rossii . Nauchnye trudy Instituta narodnokhozyaistvennogo prognozirovaniya RAN , 2006, vol. 4, pp. 535-559.

- Rybakovskii L.L. Regional'nyi analiz migratsii . Moscow: Statistika, 1973. 159 p.

- Rybakovskii O.L. Migratsiya naseleniya postsovetskoi Rossii . Vestnik Tadzhikskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta prava, biznesa i politiki. Seriya obshchestvennykh nauk , 2016, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 30-37.

- Rybakovskii O.L., Sudoplatova V.S. Postoyannaya migratsiya naseleniya rossiiskikh regionov . Narodonaselenie , 2015, no. 3, pp. 4-14.

- Ryazantsev S.V. Migratsionnaya situatsiya v Rossii i neftegazovykh regionakh Zapadnoi Sibiri . Bezopasnost' Evrazii , 2004, no. 3 (17), pp. 164-190.

- Ryazantsev S.V. Vnutrirossiiskaya migratsiya naseleniya: tendentsii i sotsial'no-ekonomicheskie posledstviya . Voprosy ekonomiki , 2005, no. 7, pp. 37-49.

- Sidorenko O.V. Formirovanie selektivnoi regional'noi politiki sotsial'no-ekonomicheskogo razvitiya problemnykh regionov: avtoref. dis.. dokt. ekon. nauk: 08.00.05. . Irkutsk: BGIEP, 2011. 39 p.

- Chernyshev K.A. Migratsii naseleniya depressivnogo regiona . Narodonaselenie , 2016, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 52-63.

- Brunarska Z. Regional out-migration patterns in Russia. EUI Working Paper RSCAS, 2014. 23 p. Available at: http://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/31382 .

- Judah B. Russia's Migration Crisis. Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, 2013, vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 123-131.

- Kashnitsky I. Cohort Research on Russian Youth Intraregional Migration and Education. Beder Journal of Educational Science, 2013, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 22-30.

- Wegren S., Drury C. Patterns of Internal Migration during the Russian Transition. Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 2001, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 15-42.