The Svalbard fisheries protection zone: how Russia and Norway manage an Arctic dispute

Автор: Sthagen Andreas, Jrgensen Anne-Kristin, Moe Arild

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Political processes and institutions

Статья в выпуске: 40, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Svalbard and the maritime zone around this Arctic archipelago are central to Norway-Russia relations. Since 1977, a dispute has concerned Norway's right to exercise jurisdiction over fisheries. What are Russian positions on Norwegian jurisdiction enforcement in the Fisheries Protection Zone (FPZ)? How have perceptions and reactions evolved since the turn of the millennium? Has the deterioration in the bilateral relationship post-2014 sharpened the dispute in the FPZ, and has the risk of conflict increased? We find that 2014 does not appear to be a watershed with respect to relations in the FPZ around Svalbard. After the dramatic arrest of a Russian trawler in 2005, the Russian central authorities switched from protest to relatively conciliatory dialogue - with a marked exception in 2011 related to Russian domestic discord surrounding the 2010 Barents Sea maritime boundary agreement. After 2011, incidents in the FPZ have been handled without further escalation, but the situation is underpinned by various factors that might change. Russia’s policies in the FPZ have been a balancing act: always stressing its official position and insisting that there are limitations to how much Norwegian enforcement can be accepted, while also ensuring that the enforcement regime survives.

Fisheries protection zone, svalbard, Russia, coast guard, arctic

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318383

IDR: 148318383 | УДК: 347(470+481)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2020.40.183

Текст научной статьи The Svalbard fisheries protection zone: how Russia and Norway manage an Arctic dispute

The Svalbard archipelago, located between the Norwegian mainland and the North Pole, occupies a special international relations position. For centuries it remained a no man's land, despite extensive economic activity in whaling, hunting, and fisheries. Only in the early 20th century did the great powers agree that Norway should have sovereignty over the islands, as stated in the Svalbard Treaty signed in Paris in 1920. Due to their economic interests, special provisions on access, taxation, and non-discrimination applied – and still apply – to economic activity on this Arctic Archipelago.

When the concept of extended maritime zones emerged in the post-war period and states subsequently implemented these, a problem arose. Did the special Svalbard provisions apply to these new maritime zones, although the zones themselves were not specified in the Svalbard Treaty? Norway has continued to argue against this, whereas other states with an economic and political interest in Arctic waters – like Iceland, Russia, and the UK – take a contrarian position. Norway subsequently implemented ‘only’ a Fisheries Protection Zone (FPZ) in 1977 – in contrast to a full Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) –to avoid an outright conflict over the issue. Still, other states with an economic and political interest in Svalbard continue to dispute the Norwegian approach.

Svalbard is close to Russia (Svalbard’s maritime zones border those extending from Frans Josef Land), and Russia is the only country besides Norway that has a sizeable population living and working on Svalbard, constituting a community on its own in the mining town of Barentsburg. Russia has argued against Norway’s right to unilaterally establish any form of the maritime zone, which has been described as a decision in violation of the Treaty of 1920. A dispute between the two Arctic neighbors thus emerged in the 1970s, which remains unresolved.

From time to time, the dispute emerges on the political agenda in relations between Norway and Russia or in Arctic governance discussions more broadly. Moreover, at times this legal dispute gives an impression of immediate risk of conflict between a small state and its big neighbor. There is a potential for clashes, particularly in the interaction between Russian fishing vessels and Norwegian authorities enforcing regulations. Further, in Norway and in NATO, there is a growing awareness of the North Atlantic/Barents Sea as an area where Russia’s military efforts are increasing.

Although other countries besides Russia holds an interest in the Svalbard maritime dispute, Russia is undoubtedly the most central actor when unpacking the complexities of this dispute. Therefore, in this article, we want to clarify Russia’s interests, positions, and behavior concerning the FPZ. What are Russian perceptions of Norwegian politics in the FPZ? How have perceptions and reactions developed after Norway tightened its enforcement practices in the zone around the turn of the millennium? Have there been changes in connection with the deterioration in the bilateral relationship after 2014? What does this mean for the risk of conflict in this area?

We seek to identify factors that may increase or reduce the risk of serious conflict. The purpose is thus not to give a complete overview of all Russian positions (or actors with a position) on the Svalbard maritime dispute, but rather to make use of the events in the FPZ over the last two decades in order to examine how statements – both official and unofficial – as well s actions concerning the zone have fluctuated and altered character, and explain why. We begin by placing the FPZ in the larger context of Barents Sea fisheries and then review and analyze developments in Norwegian management of the zone and the Russian response, highlighting the constellation of actors on the Russian side at federal and regional levels. Finally, we discuss how to explain the variations in perceptions and reactions over time and what implications can be drawn regarding the future conflict in the area.

The article is based mainly on written sources, especially Russian media outlets, journal articles, expert comments, and interviews. The bulk of this material was collected in 2018 and 2019. We also lean on writings about Svalbard and the particularities of this part of the world, either examining the archipelago on its own or as part of the larger Arctic governance system. In addition, we have conducted formal interviews and informal conversations with relevant actors on the Norwegian side. All interviewees are key participants in Norwegian fisheries cooperation with Russia. Informal discussions with a few Russian participants have added to our understanding of Russian positions.

Svalbard and the Fisheries Protection Zone

Svalbard is located approximately 650 kilometers north of the Norwegian mainland and just 1,000 kilometers from the North Pole. Initially named Spitsbergen by the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz in the Sixteenth Century, Spitsbergen is today the name of the largest island in the archipelago while the archipelago was renamed Svalbard from 1925. Only in the early 20th century, when promising discoveries of coal were made and mines opened, were specific steps taken to establish an administration of the Svalbard archipelago. Various models were discussed before the First World War; post-war negotiations resulted in a treaty that gave sovereignty to Norway 2.

These negotiations were annexed to the peace settlements which did not involve Russia and Germany. However, as Russia had played a major role in earlier talks on the status of the archipelago, the Treaty assigned to Russia the same rights as the signatories until it could formally accede. In 1924, the Soviet government unconditionally recognized Norwegian sovereignty over the archipelago and acceded to the Treaty in 1935.

A key objective of the Treaty was, after assigning Norway ‘full and absolute sovereignty’ and responsibility for managing the islands, to secure the economic interests of nationals from other countries. This was done by including provisions on equal rights and non-discrimination in the most relevant economic activities: Norway could not treat other nationals less favourably than its own citizens; and taxes levied on Svalbard could be used solely for local purposes. Regardless, international economic interest plummeted, and soon only Norwegian and Soviet mining companies had activities there. Soviet attempts to gain special status on Svalbard were expressed in the aftermath of WW2 and later. The USSR was particularly concerned about possible military use, demanding strict adherence to the Treaty’s ban on the use of the islands for warlike purposes and construction of fortifications or naval bases.

Developments in the law of the sea from the 1950s onwards extended the coastal states’ exclusive rights to resources in the seabed as well as in the water column. Such rights were codified in the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention in 1982, but they had become customary law well before then. In 1976 Norway declared a 200-nm Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) off its coast. According to the Norwegian government, Norway, as the coastal state of Svalbard, was entitled to establish an EEZ around the archipelago, as the non-discriminatory provision in the Treaty referred only, and explicitly, to the islands themselves and their territorial waters.

However, this view was disputed by some other states. The status of the water column was an urgent issue since Norway saw a need to manage the ongoing international fisheries in the area. To avoid recourse to legal proceedings, Norway simply established a Fisheries Protection Zone (FPZ) in 1977. Management of the FPZ would be on a non-discriminatory basis: fishers from Norway and from other nations would be treated equally, although access to the zone would be granted only to vessels from nations traditionally active in the area. Norway maintained that the zone was in line with the Treaty’s ‘equal treatment’ provisions 3, even if its establishment was a unilateral Norwegian decision.

This arrangement in the FPZ satisfied several states who had voiced opposition to Norway’s insistence on exclusive resource rights, notably the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark [1, Pedersen T., Henriksen T., pp. 146]. However, other states with extensive fishing rights were still critical, primarily Iceland, Spain and Russia, although their positions were not identical.

The Russian official position, expressed in diplomatic notes, has been that Norway had no right to unilaterally establish a fisheries protection zone: fisheries in the waters around Svalbard should have been the subject of bilateral negotiations between Norway and Russia.4 This was the position of the USSR when Norway established the FPZ; it remains Russia’s position today, reiterated by Russian legal scholars arguing that Norway has no legitimate right to enforce fisheries regulations around Svalbard. The waters are international, and regulations – which can be set only by international fisheries organizations – can be enforced by the flag state alone, in this case Russia [2, Vylegzhanin A. N., Zilanov V.], [3, Pedersen T., p. 34].

To understand Russia’s position regarding this zone, we must also examine explicit interests. The primary (economic) interests in the area concerns fisheries. Despite the disagreement over the legal status of the FPZ, Norway and Russia, and earlier the Soviet Union, have a long history of cooperation in management of Arctic fisheries 5. When 200nm EEZs were introduced, the two countries established a Joint Fisheries Commission for cooperation on the management of fish stocks in the whole Barents Sea, which comprises the Soviet/Russian EEZ, the Norwegian EEZ and the waters around Svalbard.

The two countries decided to treat the most important stocks (cod, haddock, capelin) as shared stocks. They institutionalized annual negotiations on the total catch limits (quotas) and agreed on a fixed distribution of these quotas (50/50). Despite problems with overfishing in the 1990s, and occasional disagreements on the total quota, this cooperation generally functioned well, and evolved to include increasingly sophisticated regulations [4, Sergunin A.]. Many observers have deemed it among the best managed international fisheries agreements in the world [5,

Eide A., Heen K., Armstrong C., et al.], [6, Jakobsen T., Ozhigin V.K.], and in 2013 the Northeast Arctic cod stock reached an all-time high 6.

There are no separate quotas in the FPZ for Norway and Russia: catches there are within the quotas set for the whole Barents Sea. Beyond doubt, Barents Sea fisheries are important to Russia – altogether they represent 10–15 per cent of Russia’s total global catch of marine living resources, probably constituting an even larger share in terms of value.7 Fisheries in the FPZ are an important part of this picture. The Russian fishing fleet takes about a quarter of its catches in the Barents Sea in the FPZ alone, and Russia has the largest annual catch among the nations active in the zone. Russian catches there have been increasing recently, as stocks like cod and haddock have extended their distribution towards the north.

The importance of the FPZ for the Russian fishing fleet must be seen in light of the fact that Russia takes a relatively small share of its catches in the Russian Economic Zone (REZ), where fish are predominantly young and small, and weather and ice conditions are complicated [8, Zilanov V.]. Access to both the Norwegian Economic Zone (NEZ) and the FPZ is vital to the Russian fishing fleet, and it is quite clear that Russia has strong material interests in the FPZ. How, then, have Norway and Russia interacted and engaged over the Svalbard maritime dispute? How have Russian interests and concerns been reflected in Russia’s practical policies towards both Norway and the Zone? How have Russia’s policy response varied over time, ranging from the late 1990s, when the Norwegian Coast Guard initiated a more stringent enforcement policy in the Zone, up to 2014 when bilateral relations between the two countries deteriorated? And what does this mean for the potential for conflict over this issue?

Russian reactions and responses to the Norwegian FPZ policy over two decades

The FPZ was established in 1977, but the first twenty years of its existence saw few signs of confrontation. The Norwegian Coast Guard practised lenient enforcement of regulations, with warnings as the strongest form of reaction used. Russian fishers had instructions from their own authorities to facilitate inspections, but refrain from catch reporting and signing any inspection forms – as a symbolic indication that the Soviet Union and later Russia did not recognize Norwegian authority in the zone [2, Vylegzhanin A. N., Zilanov, V.]. According to some Russian observers there was a mutual understanding that the Soviet Union accepted Norwegian Coast Guard’s inspection of Soviet vessels, while Norway, in turn, acknowledged that it was the flag state’s prerogative to impose any sanctions [9, Portsel A. K.], [10, Tsypalov V.], [11, Zilanov V.].

However, from 1993, the Coast Guard began to employ arrests and other means of force in the FPZ against third-country vessels fishing there without quota [12, Kosmo S.]. And from the late 1990s came a shift in Norwegian enforcement also towards Russian vessels. Norway abandoned its previous practice of ‘lenient’ enforcement in order to respond adequately to cases of serious fisheries crime.

From a Norwegian perspective, this development represented a normalisation. In a period characterised by good-neighbourly relations between Norway and Russia, enforcement of fisheries regulations was no longer seen through a foreign policy prism, but was regarded as the responsibility of regular administrative bodies. It has been argued that the tougher response to rulebreakers was initiated not at the political level, but by the administration (the Coast Guard and the State Attorney in Troms and Finnmark counties), seeking better control of the rapidly declining cod stocks [12, Kosmo S. p. 46], [13, Østhagen A. p. 108]. However, many on the Russian side perceived this tightening of control as a breach of contract, given the ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ between the two countries. When the ‘agreement’ was broken, it gave rise to strong reactions. The Norwegian side, however, has never acknowledged the existence of such an agreement.

Phase I, 1998–2005: Unanimous criticism of Norway’s new line

In 1998, for the first time, the Norwegian Coast Guard arrested a Russian trawler, the Novokuybyshevsk , in the FPZ. Several fishing grounds in the zone had been closed due to large quantities of small fish in the catches [14, Skram A-I.]; when the Novokuybyshevsk was arrested, it was in a group of about 50 Russian fishing vessels, all fishing in a closed area [12, Kosmo S. pp. 32]. The arrest provoked loud reactions in Russia. After ‘diplomatic intervention’, the charges were withdrawn, and the trawler, which had been escorted to Tromsø in North Norway, was released [3, Pedersen T. pp. 35]. Nevertheless, the incident fuelled the existing antipathies towards Norway in Russian fisheries circles: the once-friendly bilateral atmosphere had been replaced by a colder climate.

In the years around the turn of the millennium, Norwegian–Russian fisheries cooperation was characterized by disagreement on several important management issues, including the size of the annual total allowable catch [15, Hønneland G., Jørgensen A-K.], and there was considerable criticism of Norway – from fishers, military elites and regional politicians. Fishers complained about stricter regulations and stricter enforcement, many of them alleging that Norway’s longterm goal was to expel the Russian fishing fleet from the FPZ. Representatives of the military, for their part, argued that Norway was acting as a tool of NATO in the High North [16, Jørgensen J. H.]. Murmansk Governor Yuriy Yevdokimov demonstrated his concern for both fishing and defence interests by launching a sponsorship scheme for Russian fisheries inspection vessels (so that they could afford to go to sea and ‘protect’ the fishers), as well as an ‘adoption scheme’ for submarines of the Northern Fleet [15, Hønneland G., Jørgensen A-K.], [16, Jørgensen J.H.]. A core narrative was that Norway (once again) was exploiting Russia’s temporary weakness.

Recently, discrimination against Russian interests has become an everyday phenomenon (…) Norway is running a ‘silent’ campaign to expel Russian fishers from the Svalbard zone (...) In the Soviet period, there were no serious incidents.

Norway did not want to argue with its strong neighbour in the East. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it was decided in Oslo that it was time to act. The Norwegians obviously believed that Russia was not able to fully defend its interests and began purposefully to expel Russian fishers from the zone... 8

The Russian federal authorities were more restrained in their reactions, but they most likely assumed that new arrests would not occur. And indeed, an incident in 2000 similar to the Novokuybyshevsk, involving an unnamed vessel, was solved by ‘diplomatic means’ 9. But when the trawler Chernigov was arrested, prosecuted and fined for serious violations in 2001, Russian official reactions were sharp: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MID) delivered a note – leaving out the usual diplomatic courtesy phrases – accusing Norway of violating international law [3, Pedersen T. p. 25]. In addition, Russian participants at a meeting of the Permanent Committee under the Norwegian–Russian Fisheries Commission were recalled on short notice – obviously on orders from the highest level [12, Kosmo S.]. Russia also deployed the naval cruiser Severomorsk to the FPZ in 2002 to protect Russian fishers against the Norwegian Coast Guard 10.

Phase II, 2005–2012: Central Power vs. Opposition

After the uproar around the Chernigov case, the next four years saw no arrests. In 2005, however, the FPZ controversy re-emerged with force, caused by the unsuccessful arrest of the Russian trawler Elektron, which had been under surveillance for some time by the Norwegian Coast Guard for illegal discarding of fish in the FPZ. The vessel was inspected, and serious violations were uncovered, including the use of an illegal, small-meshed trawl net inside the ordinary one [17, Fermann G., Inderberg T. H. J. pp. 374-376]. The trawler was then arrested and escorted by the Coast Guard vessel KV Tromsø towards the Norwegian mainland for the police to continue with the prosecution.

The captain of the Elektron, in agreement with the Russian owners, had other plans. Just before entering the Norwegian EEZ he fled, with two Norwegian inspectors onboard. For three days, four Norwegian Coast Guard vessels, as well as a maritime surveillance aircraft and several helicopters, pursued the Elektron, closely tailing the trawler as it headed for Russian waters, where the Russian Navy was waiting. The Norwegian Coast Guard had considered boarding the trawler, but, in the end, bad weather was blamed for not following through [18, Åtland K., Ven Bruusgaard K. pp. 341]. It is also highly likely that the Norwegian authorities were concerned about the escalation effect such action could have vis-à-vis Russia [17, Fermann G., Inderberg T. H. J. pp. 389, 395].

Constant media coverage kept the case high on the political agenda in Norway. The event also received considerable attention in Russia, primarily because of the spectacular chase. However, official reactions on the Russian side were more mixed than in the Chernigov case. MID was low-key in its comments to the press, and Foreign Minister Lavrov explained, as the chase went on, that the Russian side was in constant contact with ‘The Norwegian Coast Guard, the Norwegian MFA and other Norwegian authorities’ 11. The head of the Murmansk Border Service denied that the arrest had been in violation of international law though [18, Åtland K., Ven Bruusgaard K. pp. 341], while the head of the Russian delegation to the Joint Fisheries Commission stated, ‘the Norwegians, understandably, had to respond to the uncontrolled fishing that goes hand in hand with [Russia’s] passivity’ 12.

At the regional level in Murmansk, on the other hand, there were crass statements against Norway, both from shipowners and local politicians. Their anger was also directed at their own authorities – the military and the Federal Security Service (FSB) were criticized for their unwillingness to protect Russian citizens 13. In the media, the captain of the Elektron was partly hailed as a hero and partly portrayed as a criminal who had embarrassed Russia.

Thus, starting with the Elektron case, we see a distinction between a dialogue-oriented central power and a conflict-oriented ‘opposition’ concerning the FPZ. Lavrov’s desire for bilateral discussions was followed up in the Joint Fisheries Commission, where the fisheries around Svalbard became a regular item on the agenda from 2005. In the ensuing years, the parties appeared to reach a mutual understanding of the need to react to violations in the Zone. Between 2006 and 2010, six trawlers were arrested in the FPZ, without triggering formal protests from Russia [13, Østhagen A. pp. 107-111]. The focus of the Russian delegation to the Joint Fisheries Commission was to reach an agreement on harmonization of Norwegian and Russian fishing regulations 14. And in 2009/10, the parties agreed on common rules for mesh size in trawls, minimum size limits for fish and regulations concerning closing/opening of fishing grounds. Russian fishers had long complained about having to follow Norwegian rules when fishing in the FPZ, so this was an important conflict-dampening measure.

In practice, the Russian fisheries authorities’ civilian surveillance vessels had little to contend with against the Norwegian Coast Guard [19, Åtland K.]. At a meeting of the ‘Russian government commission for provision of Russia’s presence on the Spitsbergen archipelago in December 2011 the possibility of using the Northern Fleet, as well as strategic, long-range bombers pa- trolling the Arctic Ocean, to demonstrate strength was discussed, although direct military intervention in fisheries disputes was not considered [9, Portsel A. K. pp. 14-15].

Intermezzo 2010–2011: Turmoil surrounding the maritime boundary agreement and the Sapfir-2 case

In 2011 – when the agreement had been ratified and had entered into force – a total of five Russian trawlers were arrested by the Norwegian Coast Guard in the FPZ, and the fishers and their supporters understandably felt vindicated [24, Glubokov A.I., Afanasiev P.K., Mel’nikov. S.P.] Fisheries representatives and local politicians in Murmansk described the arrests as ‘aggressive acts’ aimed at ‘driving’ Russian fishers out of the Barents Sea [25, Nevskoe vremya]. They also had harsh words to their own authorities: for example, a representative in the Murmansk Parliament accused MID of taking the [Norwegian] ‘intruders” side (ibid.)

The controversy peaked in autumn 2011, when the Russian trawler Sapfir-2 was seized for discarding fish. Russian media described the arrest as unusually dramatic. Also in this case, the captain called on a Russian state vessel, Angrapa, for help, and media reports conveyed the impression that the Norwegian Coast Guard inspectors acted brutally to prevent Russian inspectors from coming to the rescue.15 There had been no official protests against arrests earlier that year, but now MID delivered a sharp note to the Norwegian ambassador, declaring that Norway’s actions had an ‘unacceptable and challenging character’, and specifically noting the many recent arrests in the FPZ [9, Portsel A. K.].

At the meeting of the Joint Fisheries Commission a few weeks after the arrest, the mood was tense 16. At Russian request, an extraordinary session was held in February 2012 on fishing around Svalbard. Here it was agreed to ‘prepare as soon as possible’ a unified definition of the term ‘discard’. In addition, a working group was to prepare common guidelines for inspections [7, Hønneland G.].

Phase III, 2012–2018: Control and attenuated reactions

Since 2012, there has been much less turmoil over the FPZ internally in Russia. The arrests that have taken place in the zone after 2011 have received scant media coverage; articles and commentaries about the FPZ generally refer to older cases ( Elektron , Sapfir-2 ). In the spring of 2017, however, the arrest of the Norwegian trawler Remøy in the REZ, which was held back for three weeks as well as receiving a stinging fine for what the Norwegians saw as a technical registration error by the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries, received extensive coverage in the Northwest Russian media 17. In Norway, it was speculated that the arrest could be ‘revenge’ for humiliating arrests of Russian vessels in the past 18.

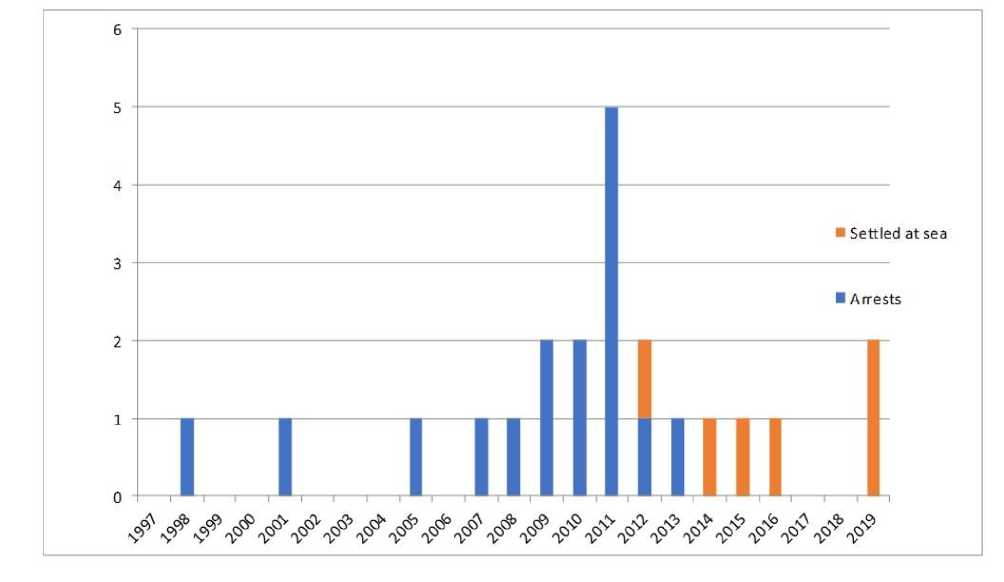

An important reason why the debate around the FPZ has now stalled is probably the relatively few arrests of Russian vessels in recent years (see Table I). Importantly, most of these cases – and all cases after 2013 – have been ‘resolved at sea’. Under this procedure which was introduced in 2012 by the Norwegian side, arrested vessels are not brought to a Norwegian port, but are released when a guarantee for payment of imposed fines has been produced 19. Prior to the introduction of this scheme, there were frequent complaints from Russian vessel-owners that only foreign fishing vessels were forced to go to a Norwegian port after being arrested in Norwegian jurisdictions. The shipowners saw this as discriminatory, as it entailed lost fishing time and income, in addition to the fine. The Norwegian Coast Guard believes that the new scheme has offset con-flict20 – a view supported by the relative silence on the topic of arrests in the Russian media.

Table 1

Overview of Norwegian Coast Guard arrests in the FPZ. 1997–2019. Data from the Norwegian Coast Guard and from [14, Skram A-I. p. 151].

Nevertheless, the sailing has not always been smooth. Criticism of the Norwegian Coast Guard’s inspection practices has come from several corners (see, for example, [26, Sennikov S. A.]) and Chairman of the Coordination council for northern fisheries (Sevryba) Vyacheslav Zilanov claimed in an interview in 2016 that inspections of Russian vessels have 'a humiliating character' 21. Particular attention has been given to discarding of fish. Zilanov complained that the rules for discarding are interpreted too strictly: ‘…if a herringbone falls overboard or the trawl accidentally splits as it is hauled, this cannot be considered a violation ...’ 22. In an email exchange with the authors in 2018, Zilanov elaborated his views:

Discarding is a Norwegian 'invention' and the Norwegians show a consistent lack of interest in giving the concept a practical interpretation. Why? [Because] this is a favourable situation for the Norwegian coast guard, so that they can continue to arrest fishers, especially Russian ones. The Norwegians are not interested in solving this problem.23

The processes initiated at the Fisheries Commission's session in 2011 (unified definition of the term 'discarding', common guidelines for inspections) were aimed at addressing exactly these Russian concerns. In the years that followed, the parties tried to find mutually acceptable solu- tions, but this proved difficult. The Russian side wanted specific and strict limitations on the duration of inspections, the number of inspectors who could normally participate, etc. Furthermore, common guidelines were sought not only for the inspection phase itself, but also for the investigation phase, which in Norway falls under the competence of the prosecuting authority.24 Negotiations on this point were not acceptable to Norway, and the work was 'temporarily' halted in 2015.

However, the atmosphere in the Joint Fisheries Commission and its subsidiary bodies has improved in recent years.25 Norwegian participants in the collaboration state that constructive work is being done to identify matters where joint solutions are possible, and that the parties otherwise 'agree to disagree'. Interviews also indicate that the deterioration in government-level Norwegian–Russian relations after 2014 has not affected the Commission's work.26

In parallel with the better climate in the Joint Fisheries Commission, the official Russian presence in the FPZ has become more noticeable. Responsibility for patrolling in the area lies no longer with the fisheries authorities, but with the Russian Coast Guard. Since its formal establishment in 2004, the Coast Guard has undergone extensive modernization, and its work is prioritized [19, Åtland, K.]. Several new, more sophisticated vessels have been added27; some of these are ice-strengthened, and at least one vessel is equipped with a helicopter.28 Despite Russia's weakened economy, there has been a moderate increase in Coast Guard patrolling in the FPZ in recent years.29 The modernization of the fleet has made it possible to conduct patrols most of the year, and the helicopter-carrying vessel Polyarnaya Zvezda is regularly observed in the Zone.30 By contrast, Norwegian capacities have deteriorated: the Norwegian Coast Guard is now without helicopters most of the time, due to serious delays in delivery of new helicopters, and its vessels are age-ing.31 However, there have been no attempts to interfere with Norwegian inspections in the FPZ since the Sapfir-2 episode back in 2011 – which involved a vessel from the regional fisheries inspection agency, not a Russian Coast Guard vessel.

Statements from representatives of the Russian Coast Guard indicate an ambition to achieve some form of parity with the Norwegian Coast Guard in the FPZ. In 2016, the head of the Border Service claimed in an interview that the agency's vessels oversee Svalbard 'together with'

the Norwegian Coast Guard, and that they inspect 'both Russian and foreign fishing vessels'.32 In an interview in 2012, the Border Service's press officer in Murmansk gave the impression that there was an agreement that the Norwegian Coast Guard should 'generally' refrain from controlling Russian vessels when Russian coastguard vessels were in the area.33

Such statements can perhaps be explained by poor information flow upwards in the system or, more likely, as 'alternative facts' intended for a domestic audience. The Norwegian Coast Guard states that there is no form of operational cooperation with the Russian side in the FPZ, other than exchanging courtesy phrases on the radio, and that joint inspections are completely out of the question – although the Russians have expressed a desire for such on several occa-sions.34 Attempts by Russian Coast Guard vessels to inspect third-country vessels in the FPZ have not been observed.35

In summary, the dust has settled in Russian fisheries circles and in the Fisheries Commission, while the Russian presence in the FPZ has increased. But at a higher level, Russia’s criticisms of Norway continue. There have been attempts to engage Norway in bilateral discussions concerning Svalbard.36 In October 2017, Russian newspapers published excerpts from a 'leaked' report from the Russian Ministry of Defence:

As a special threat, mention is made of Norway and its plans for unilateral revision of international agreements. The report underlines that the country's authorities are striving to establish 'absolute national jurisdiction over the archipelago of Svalbard and the adjacent 200-mile zone'.37

And in February 2020, in connection with the centenary of the Svalbard Treaty, Foreign Minister Lavrov sent a letter to his Norwegian counterpart listing Russian complaints, including ‘the unlawfulness of Norway’s fisheries protection zone’.38 In April 2020, MID sent a formal protest note to Norway after the arrest of the trawler Borey, explicitly referring to the Svalbard Treaty. “In the year of the 100th anniversary of this document, we urge Oslo to strictly follow the spirit and letter of the treaty” 39. On the practical level the episode was resolved after one day, as the trawl- er accepted to pay a fine 40.

Explanations, implications, and conclusions

There has been considerable variation in Russian responses to Norwegian enforcement practice in the FPZ. The strongest reactions have come from regional actors, primarily shipowners in the fishing industry and their supporters in north-western Russia. Criticism from these actors was particularly sharp around the turn of the millennium and in the time around the signing of the maritime boundary agreement but weakening after 2011. The Russian federal authorities have been more diplomatic than the fishers, but they too were initially highly critical of Norway's new line – as borne out by the absence of diplomatic niceties in the note transmitted after the arrest of the Chernigov in 2001. From the Elektron case in 2005, however, Moscow focused on a dialogue-oriented approach, except for a short period after the arrest of the Sapfir-2 .

We thus find two turning points: one in 2005, when the central power went from protest to dialogue, and one after 2011, when criticism from fishers and their supporters quieted. Interestingly, 2014 does not appear to have been a turning point, despite the deterioration in bilateral relations following the Russian annexation of Crimea. How can this be explained?

The dispute over the FPZ has more aspects than purely legal ones. Russia has extensive interests in the area, both military and economic; there is also a historical dimension, involving strong feelings. Russian observers refer both to fishing history and to the fact that early Russian marine scientists have made the greatest contributions to exploration and mapping of the stocks around Svalbard [2, Vylegzhanin A.N., Zilanov V.], [11, Zilanov V.]. There is also much to indicate that feelings of historical injustices continue to shape Russia’s perceptions of its legitimate role in the area. The fact that Russia was barred from participating in the negotiations on the Svalbard Treaty has shaped Russian perceptions of Svalbard issues in retrospect [16. Jørgensen J. H.], [2, Vylegzhanin A. N., Zilanov V.]; this narrative of the ‘weakened superpower’ was reactivated in the Russian Svalbard debate after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

In their criticism of Norway and the Norwegian Coast Guard, shipowners have mentioned all these factors, but that does not mean they carry equal weight. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Russian fishers seem mainly concerned with the practicalities of fishing. What they have feared first and foremost are deteriorating framework conditions for Russian fishing activities in the FPZ – at worst, being squeezed out of the zone. The campaign against ratification of the 2010 maritime boundary agreement, helped sharpen fishers’ fears of underlying motives on the Norwegian side.

These fears were amplified when the Norwegian Coast Guard arrested a record number of Russian vessels in the FPZ soon after the agreement went into force.

Nevertheless, the wave of protests from the 'fishery opposition' in 2010/2011 was a transient phenomenon. This may partially be explained by the region's weakened position, which made it costly for regional politicians to continue to challenge the policies of the central authorities. But we believe that a more important factor was the decline in the number of arrests from 2012 onwards – and not least the new scheme for settling cases at sea. Further, the harmonization of Norwegian and Russian fisheries regulations in the Barents Sea, as well as the work of the Joint Fisheries Commission in obtaining and distributing information on national regulations, made it easier for Russian fishers to operate both in the FPZ and in the NEZ. Regional opposition to Norwegian practices in the FPZ dwindled, since so much of it had been based on dissatisfaction among fishers.

Moscow's response pattern has been more complex. Different agencies have different priorities and sometimes different worldviews and ideological positions. The ongoing power struggle among government structures adds to the complexity. In the late 1990s, power in Russia was highly fragmented. Sector interests and private interests were evident in many political areas – not least in the fisheries sector. In the Joint Fisheries Commission, several shipowners critical to Norway contributed to a high level of conflict. When the Norwegian Coast Guard began to tighten its enforcement, Russian reactions were strong but uncoordinated.

As Vladimir Putin consolidated his power soon after the turn of the millennium, Russia emerged as a more unified actor – at least in foreign policy. This became evident when the Russian authorities were faced with the Elektron case in 2005. Given the considerable public and international attention to the story as it unfolded, there is little reason to doubt that Putin was involved in deciding how it should be handled – and the central power chose dialogue rather than confrontation. That response seems to correspond to priorities in Putin’s early presidency, with pragmatism in most areas. True, the goal was to rebuild Russia as a great power, but this could best be achieved through stabilization and economic growth. Putin was also concerned that Russia should be perceived as a reliable and responsible partner to other countries – not least in the Arctic. Several analyses have indicated that centralization under Putin helped the Norwegian–Russian fisheries cooperation to develop in a positive direction in those years.41

As Jørgensen has noted [16, Jørgensen J. H.], the absence of official protests against the arrest of Russian vessels in the FPZ could be interpreted as tacit acceptance of Norway's right to exercise jurisdiction there. However, the Russian authorities made sure to send signals that they were not prepared for any kind of infringement on Russian rights. Here, Russia followed the same line as the Soviet Union: putting mild pressure on Norway to try to achieve a special position for Russia in the region – including by promoting proposals for various joint arrangements, and by sending Russian fisheries inspection vessels to the FPZ. The deployment of ships from a modern Russian Coast Guard underscores Russia’s positions.

When the ratification of the Barents Sea boundary agreement was followed by an unusually high number of arrests of Russian fishing vessels in the FPZ, Moscow's dialogue-oriented line came under intense pressure. It would have been politically impossible for MID not to respond. The red-hot (in a diplomatic context) language used in the protest note delivered during the Sapfir-2 case testifies to strong frustration. However, the Russian authorities soon resumed a conciliatory tone. Indeed, there seem to have been no protests vs arrests of Russian vessels in the FPZ between 2012 and 2019. The period includes six cases in total, five of which occurred after Russia's annexation of Crimea. All but one was resolved at sea.

The real question is why Russia has not responded more strongly. After all, the Russian official position on the FPZ has been consistent ever since 1977: Norway has no right to unilaterally establish such a zone and enforce regulations there. Perhaps Russia does not want to risk an open conflict in the Zone, for instance by using force to prevent Norwegian Coast Guard interven-tions?42 Given Norway’s NATO membership, such a conflict could escalate to dangerous levels. While it cannot be ruled out that such calculations play a role for central decision-makers, we hold that concern for Russian fisheries interests has more explanatory power.

This may seem paradoxical, as we have concluded that disputes about Norwegian enforcement in the FPZ have brought strong reactions from Russian fishers. However, ‘Russian fishing interests’ can be understood more broadly. As noted, Russian fishers catch considerable quantities in the Zone very year. Crucially, the FPZ keeps newcomers out, and third-nation vessels must fish within quotas allocated by Russia or Norway – as a share of their respective Barents Sea quotas. As third-country vessels must also comply with Norwegian regulations, the Zone protects Russian fisheries interests well. If Russia were to sabotage Norwegian jurisdiction to such an extent that the FPZ effectively broke down and the official Russian position – that these areas are international waters – were realized, third-country vessels would basically have free rein – to the detriment of Russian fishers. This paradox is understood by many, but not all, in Russia.

Logically, then, if the FPZ is so important for Russia, why does the country not formally recognize Norwegian jurisdiction? This would be a step too far, as it would collide with overarching Russian priorities and ambitions in the region. Russia has consistently argued for interpretations of international agreements, be they UNCLOS or the Svalbard Treaty, that serve to maximize Russian interests. In this respect Russia is not much different from other countries. But in the Arctic, Russian interests are stronger than those of many other states. Russian policies in the FPZ have been a balancing act: always underscoring its official position and demonstrating that that there are limitations to how much Norwegian enforcement can be accepted – while also making sure that the enforcement regime survives, e.g. by formally instructing Russian fishing vessels to accept Norwegian inspection on board (but not sign inspection protocols) [28, Zilanov, V.]. It is not easy to maintain this balance. Forces outside the Kremlin’s control may rock the boat. Earlier episodes caused outcry in fisheries circles and regionally in Murmansk. Largely because of revised procedures for interaction between Russian fishers and Norwegian inspectors, as well as clarification of regulations, such episodes have not occurred for several years. But a situation when a Russian vessel is boarded by the Norwegian Coast Guard and calls for help from the Russian Coast Guard cannot be ruled out. In the past, responses from the Russian authorities was moderate. But today, with distinctly nationalistic trends in Russian politics, as in the media and society at large, neglecting calls for intervention when Russian fishers claim mistreatment by the Norwegian authorities could prove difficult even for Moscow. The deterioration in Norway-Russia relations also means that any situation that may arise in the FPZ will be interpreted in a more tense security policy context.

Precisely this may also help to explain the willingness to avoid such situations between the two coast guards [13, Østhagen A.]. Russian operations at sea are now under better control than before. Since 2012, patrolling operations in the FPZ have been conducted by the Russian Coast Guard, subordinate to the FSB and its Border Service. Although the FSB sees itself as the nation's (coastal) defender, and some statements may indicate a desire to get on par with the Norwegian Coast Guard in the FPZ, we assume that the Border Service will have a high threshold for direct confrontation with the Norwegian Coast Guard in the Zone. The FSB has generally acted more disciplined than the fisheries authorities; moreover, the FSB answers directly to the president and is presumably highly receptive to signals from the top – for instance, to avoid direct skirmishes.

Specific measures have been taken to avoid clashes between the Norwegian and Russian Coast Guards. Several studies have highlighted the importance of contact and dialogue to avoid conflict escalation and crisis situations.43 As Østhagen shows [13, Østhagen A. pp. 118-120], there is close dialogue between the two Coast Guards, with regular drills in the Barents Sea, annual exchanges of fisheries inspectors and personnel between headquarters, and sharing of relevant information as needed.44 Although the 2014 Ukraine conflict brought some restrictions, dialogue has generally been maintained [27, Østhagen A. p. 53]. An important element is the person-to-person contact, at the official and the operational levels [15, Hønneland G., Jørgensen A-K.]. This is not just about meeting points, but also about continuity. Keeping the same people in key roles over time fosters personal relationships. This contributes to the development of trust, and to the formation of a commonality of interest: a group of people who approach the same problems (fisheries conflict, search-and-rescue operations, oil spills) in the same way. Also positive is the Norwegian Coast Guard's emergency assistance to Russian fishers. Its dual role, as enforcer of fishing regulations and as 'merciful Samaritan' towards Russian fishers, helps to build a community of shared interest and creates goodwill on both sides. Another important forum for dialogue is the joint Norwegian–Russian Fisheries Commission. Moreover, the Arctic Coast Guard Forum has been established, focusing on practical multilateral cooperation.

Of course, cost–benefit calculations are the basis of much of this cooperation. Sustainable management of shared fish stocks benefits both parties. Emergency preparedness and search-and-rescue services are an area where cooperation achieves more than what each country can do unilaterally. Mutual interest is vital for maintaining and furthering cooperation and dialogue. But these aspects are not static. A weakening of venues for dialogue could change personnel and undercut communication channels. Perceptions of common interests may shift. Climate change, economic downturns for fisheries, and sharply reduced quotas may challenge the situation. Changes in international power relations could also entail risks for confrontation in the FPZ.

We have not found that the events of 2014 represent a watershed as regards the level of conflict in the FPZ. As during the Soviet period, both parties seem concerned with shielding fisheries cooperation as much as possible from fluctuations in (geo)political cycles. This says something about the great value that both sides place on cooperation. It also indicates that not everything with a security-policy dimension is necessarily securitized.

Список литературы The Svalbard fisheries protection zone: how Russia and Norway manage an Arctic dispute

- Pedersen T., Henriksen T. Svalbard’s Maritime Zones: The End of Legal Uncertainty? The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 2009, no. 24 (1), pp. 141–161. DOI: 10.1163/157180808X353920

- Vylegzhanin A.N., Zilanov V. Spitsbergen: Legal Regime of Adjacent Marine Areas. Utrecht, Eleven International, 2007, 167 p.

- Pedersen T. Endringer i internasjonal Svalbard politikk [Changes in International Svalbard Policy]. Internasjonal Politikk, 2009, no. 67 (1), pp. 31–44.

- Sergunin A. Russia and Arctic Fisheries. In: Liu N., Brooks C.M., Qin T. eds. Governing Marine Living Resources in the Polar Regions. Northampton, Edward Elgar Publishing Inc., 2019, pp. 109–137.

- Eide A., Heen K., Armstrong C. et al. Challenges and Successes in the Management of a Shared Fish Stock – The Case of the Russian-Norwegian Barents Sea Cod Fishery. Acta Borealia, 2012, no. 30 (1), pp. 1–20. DOI: 10.1080/08003831.2012.678723

- Jakobsen T., Ozhigin V.K., eds. The Barents Sea: Ecosystem, Resources, Management – Half a Century of Norwegian-Russian Cooperation. Trondheim, Tapir Academic Press, 2011, 825 p.

- Hønneland G. Norway and Russia: Bargaining Precautionary Fisheries Management in the Barents Sea. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 2014, no. 5 (1), pp. 75–99.

- Zilanov V. Rossiya teryaet Arktiku? [Is Russia Losing the Arctic?]. Moscow, Algorithm Publ., 2013, 262 p. (In Russ.)

- Portsel A.K. Rossiya ostaetsya na Shpitsbergene [Russia Remains on Spitsbergen]. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2012, no. 9, pp. 1–20.

- Shchipalov V.V. Natsional'nye interesy Rossiyskoy Federatsii na arkhipelage Shpitsbergen [Russia’s National Interests on the Archipelago of Spitsbergen]. Analiticheskiy vestnik [Analytical Bulletin], 2009, no. 12 (379), pp. 66–79.

- Zilanov V. Smeshannaya sovetsko/rossiysko-norvezhskaya komissiya po rybolovstvu: ot istokov che-rez doverie k budushchemu [The Joint Soviet / Russian-Norwegian Fisheries Commission: From the Origins Through Trust in the Future]. Voprosy rybolovstva [Problems of Fisheries], 2016, no. 17 (4), pp. 460–483.

- Kosmo S. Kystvaktsamarbeidet Norge-Russland. En fortsettelse av politikken med andre midler? [Coast Guard Cooperation Norway-Russia. A Continuation of Politics by Other Means?]. Forsvarets stabsskole – Norwegian Joint Staff College, Oslo, 2010, 62 p.

- Østhagen A. Managing Conflict at Sea: The Case of Norway and Russia in the Svalbard Zone. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 2018, no. 9, pp. 100–123.

- Skram A-I. Alltid Til Stede: Kystvakten 1997–2017 [Always Present: Coast Guard 1997–2017]. Bergen, Fagbokforlaget Publ., 2017, 319 p.

- Hønneland G., Jørgensen A-K. Kompromisskulturen i Barentshavet [The Culture of Compromise in the Barents Sea]. In: Heier T., Kjølberg A., eds. Norge og Russland: Sikkerhetspolitiske utfordringer i Nordområdene [Norway and Russia: Security Challenges in the High North]. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget Publ., 2015, pp. 57–68.

- Jørgensen J.H. Russisk Svalbardspolitikk [Russian Svalbard Policy]. Trondheim: Tapir Akademiske Forlag Publ., 2010, 100 p.

- Fermann G., Inderberg T.H.J. Norway and the 2005 Elektron Affair: Conflict of Competencies and Competent Realpolitik. In: Jakobsen T.G., ed. War: an Introduction to Theories and Research on Col-lective Violence. New York, Nova Science, 2015, pp. 373–402.

- Åtland K., Ven Bruusgaard K. When Security Speech Acts Misfire: Russia and the Elektron Incident. Security Dialogue, 2009, no. 40 (3), pp. 333–353. DOI: 10.1177/0967010609336201

- Åtland K. Myndighetsutøver, ressursforvalter og livredder – den russiske kystvakten i støpeskjeen [Government Official, Resource Manager and Lifeguard – Russian Coast Guard in the Making]. Nordisk Østforum, 2016, no. 30 (1), pp. 38–54. DOI: 10.17585/nof.v30.390

- Hønneland G. Hvordan Skal Putin Ta Barentshavet Tilbake? [How shall Putin Reclaim the Barents Sea?]. Bergen, Fagbokforlaget, 2013, 152 p.

- Hønneland G. Russia and the Arctic: Environment, Identity and Foreign Policy. London, New York, I. B. Tauris Publ., 2016, 191 p.

- Ims M. Russiske oppfatninger om delelinjeavtalen i Barentshavet [Russian Perceptions Concerning the Maritime Boundary Agreement in the Barents Sea]. University of Tromsø Publ., 2013, 115 p.

- Moe A., Fjærtoft D., Øverland I. Space and Timing: Why Was the Barents Sea Delimitation Dispute Resolved in 2010? Polar Geography, 2011, no. 34 (3), pp. 145–162. DOI: 10.1080/1088937X.2011.597887

- Glubokov A.I., Afanasiev P.K., Mel’nikov S.P. Rossiyskoe rybolovstvo v Arktike – mezhdunarodnye aspekty [Russian Fisheries in Arctic – International Aspects]. Rybnoe Khozyaystvo [Fisheries], 2015, no. 4, pp. 3–10.

- Sennikov S.A. Mezhdunarodnye dogovory Possiyskoy Federatsii kak pravovaya osnova rybolovstva v morskom rayone arkhipelaga Shpitsbergen [Treaties of the Russian Federation as Legal Basis for Fisheries in the Maritime Area of the Spitsbergen Archipelago]. Evraziyskiy yuridicheskiy zhurnal [Eurasian Law Journal], 2014, no. 7 (74), pp. 88–91.

- Østhagen A. Coast Guards and Ocean Politics in the Arctic. Singapore, Palgrave Pivot, 2020, 99 p.

- Zilanov V. Arkticheskoe razgranichenie Rossii i Norvegii: novye vyzovy i sotrudnichestvo [Delimita-tion Between Russia and Norway in the Arctic: New Challenges and Cooperation]. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2017, no. 29, pp. 28–56. DOI 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2017.29.28