The Tamga signs of the Turkic nomads in the Altai and Semirechye: comparisons and identifications

Автор: Rogozhinsky A.E., Cheremisin D.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145430

IDR: 145145430 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.2.048-059

Текст обзорной статьи The Tamga signs of the Turkic nomads in the Altai and Semirechye: comparisons and identifications

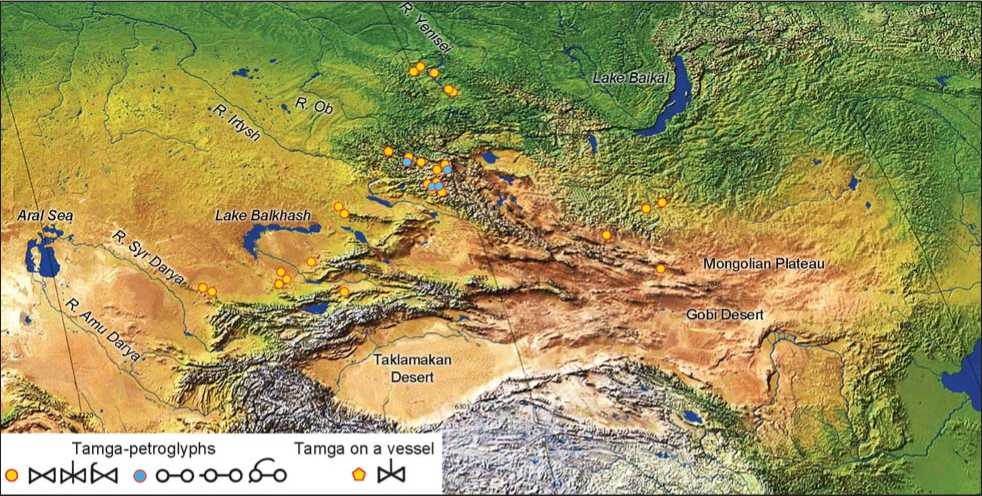

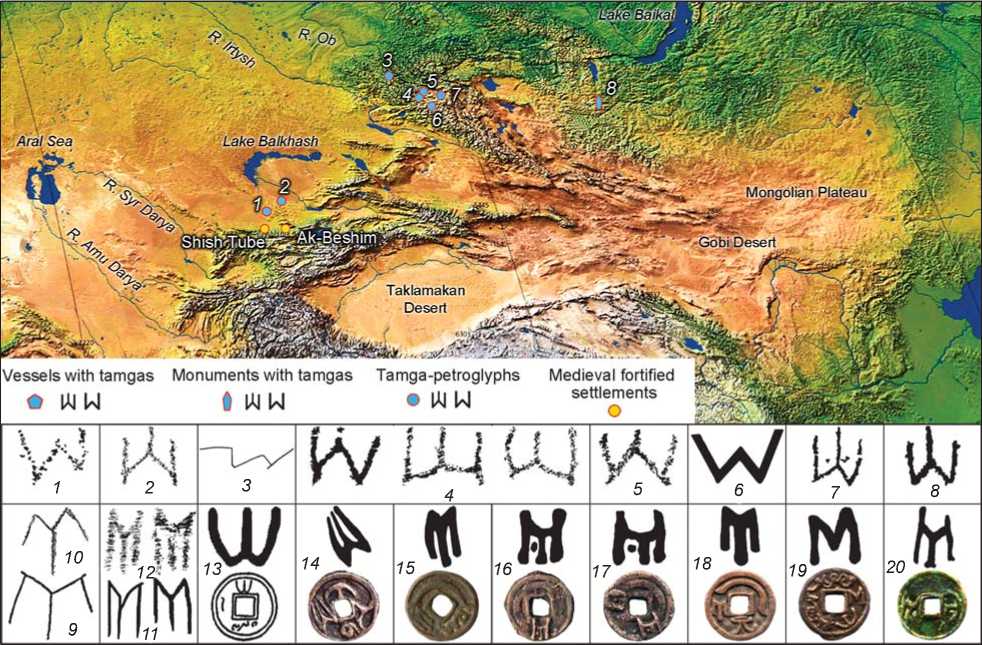

Ancient and medieval tamgas known from the vast territories extending from the Cis-Baikal region to the Caspian Sea, and from the Kuznetsk Alatau and Khangai Mountains to the Tian Shan and Pamir-Altai appear on two types of monuments: portable items and immovable monuments of archaeology and architecture (Fig. 1). Tamgas have been found on memorial and cultic structures (steles, funerary enclosures, balbal steles, tombstones, temple buildings), and in the form of rock paintings: a) in accumulations of petroglyphs (“sanctuaries”); b) near permanent sites, and c) as separate collections of tamga signs (“encyclopedias”), which represent an independent type of historical and cultural monument traditionally referred to as tamgalytas in the Turkic-speaking part of Central Asia. Tamga signs are depicted on the following portable items: a) coins of the ancient states of Transoxiana (the Kushan Empire, Khwarazm), vassal possessions of the Turks in Central

coins petroglyphs ctures steles)

cultic and household items funerary stri< (tombstones

Monuments with tamgas immovable items memorial and cultic structures separate accumulations locations of sites of petroglyphs (“sanctuaries”) z temple buildings portable items cultic and household items collections of signs (tamgalytas^

prestigious products military and horse equipment

Fig. 1. Classification of monuments with tamgas. Compiled by A.E. Rogozhinsky.

Asia, and urban centers in the Chuy and Talas valleys; b) on cultic and household items, prestigious products (expensive dishware, seals), and items of military and horse equipment (Rogozhinsky, 2014: 82). The tamgas on immovable items have the greatest informational value for the study of land use, settlement, and movement of nomadic tribes. They mark long-term habitation locations and areas of various nomad groups over a particular period of time.

Medieval tamgas have been found at monuments of all the above types on the territory of the Altai in Russia, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan. To date, about 50 locations are known, but this figure reflects only our relatively poor knowledge of the mountainous region. Typologically, about 20 basic forms of tamgas have been identified; some of them have from two to seven varieties. In Semirechye, over 150 locations with tamgas on rocks and memorials have been found; about 30 types of signs have been identified, many of which appear in three to six varieties.

Groups of tamgas: description and identification

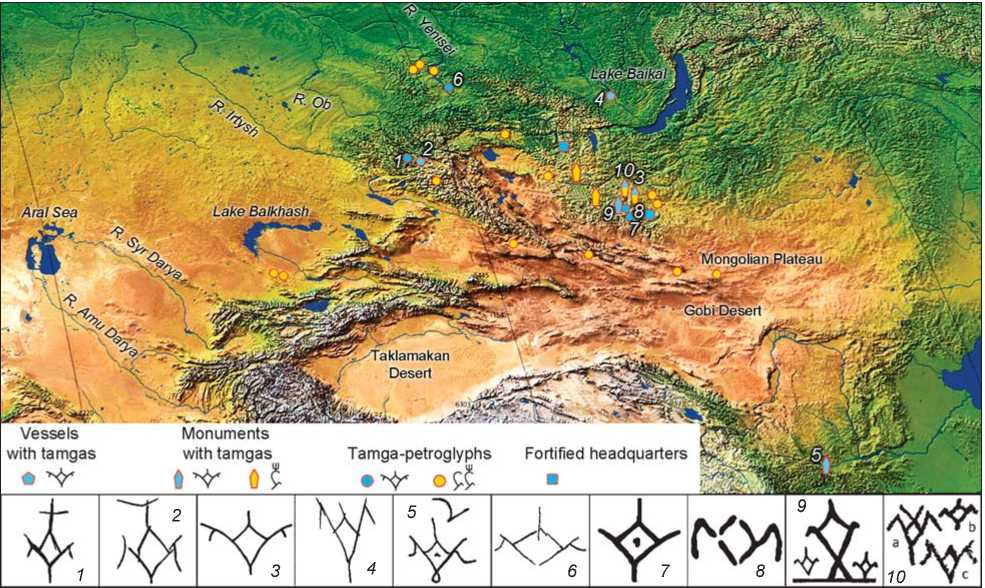

Frequent occurrence of some signs at many locations of the Altai suggests the long-term stay of their owners. These signs include the tamga in the form of two connected circles; several of its varieties, which were composed by adding diacritical elements to the main figure, are known (Fig. 2). Tamgas of this type have often been found in the Russian and Mongolian Altai (Kubarev V.D., Tseveendorj, Jacobson, 2005: App. I, fig. 937, 1050, 1248, 1345; Kubarev V.D., 2009: App. I, fig. 399, 440, 562; Vasiliev, 2013: 117–121), but outside of that territory, this “endemic” sign is rare.

Another group consists of tamgas that occur, in addition to the Altai, in many regions of Central Asia. For instance, the tamga in the form of a pair of connected triangles (up to six varieties) commonly appears in the Altai and Semirechye; it is less common in Southern Kazakhstan, the Northern Tian Shan, in the center of Mongolia, and in the Minusinsk Basin. In the Altai, this tamga has been repeatedly discovered on memorials; in Semirechye only on petroglyphs. This tamga could have belonged to a large association of nomads in the Altai, whose units at certain periods occupied the territories of the Central Asian possessions of the Turks.

Rare tamgas located outside of the Altai can be viewed as a result of penetration of certain groups of migrant population or their representatives into the local environment. Such tamgas include the sign on the Syrnakh-Gozy rock and on a vessel from the Kurai I site (Kubarev G.V., 2012: 199, fig. 2), which can be identified as a dynastic tamga of the Yaglakar (a Khagan clan of the Uyghurs) on the basis of the Kary Chortegin bilingual (775–795) from Xian (Alyılmaz, 2013: 52–53; Luo Xin, 2013: 76–78). Such tamgas are very rare; they are noteworthy because of the high political status of the emblem that has been found only on four memorials in Mongolia and China (Bugut, Mogoyn Shine Usu, Shivet

Fig. 2. Locations of tamgas.

Fig. 3. Locations of tamgas.

1 – Syrnakh-Gozy; 2 – Kurai I; 3 – Mogoyn Shine Usu; 4 – Muruisky Island, vessel 1; 5 – Xian (Kary Chortegin); 6 – Tepsey (E 116); 7 – Zuriyn Ovoo; 8 – Khurugiyn Uzur; 9 – Bugut; 10 – Shivet Ulan. 2 , 4 , 5 , 10 – drawings of the tamgas by A.E. Rogozhinsky.

Ulan, and the epitaph of Kary Chortegin), two silver vessels from Kurai I and from Muruisky Island, and in a form of a petroglyph in Syrnah-Gozy, Tepsey, Zuriyn Ovoo, and Khuriyn Uzur (Fig. 3, 1, 6–8). The most important of these monuments are associated with the “domain” (kurug) of the rulers of the Uyghur Khaganate on the northern slopes of the Khangai Mountains (Klyashtorny, 2012: 95), and petroglyphs of the Khagan emblem on the Yenisei River (Tepsey) and in the Chuy Valley (Syrnah-Gozy) may mark the distant borders of the territories, which at a certain moment became influenced by the Uyghurs.

A single find in the Mongolian Altai is a tamga associated with the Uyghur tribal union (Esin, 2017: Pl. 2). This petroglyph sign from Tsagaan Salaa IV represents the main form of the tamga, which is known in no less than five more complex varieties. The area where the main tamga and its varieties occur includes at least 16 locations on the rocks and memorials of Mongolia from the borders of the Gobi to the northern spurs of the Khangai Mountains (Fig. 3). Beyond this area, the tamga was found in individual locations in Central Tuva (Belikova, 2014: 101, fig. 23), Semirechye, as well as on a vessel from Muruisky Island on the Angara River. It can be assumed that the remote tamga locations mark the direction of the Uyghur expansion during the period of their elevation (submission of the Tuva Chik in 750– 753 and of the Yenisei Kyrgyz in 758) (Kyzlasov L.R., 1969: 57–58; Kamalov, 2001: 89–90), and the subsequent movement of individual groups of the Uyghur population to the west and southwest after the defeat of their state by the Kyrgyz (Malyavkin, 1974: 7).

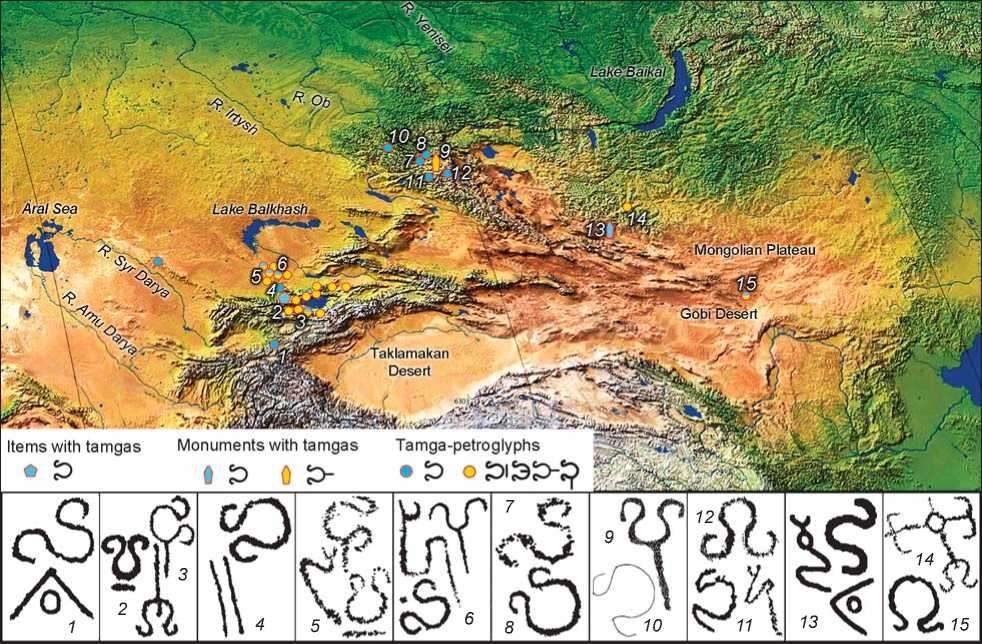

There is a group of widespread tamgas that often appear in combination with tamgas of other types. Three signs belong to this group: No. 1 – similar to the Greek letter “omega”; No. 2 – in the form of a winding snake, and No. 3 – in the form of an angle with a circle between the rays or short lines on one of them. The areas of these signs mostly coincide, although they do not form a single space, which can be explained by the uneven degree of research on different territories. The common area of the three signs consists of two remote areas: a) the Russian and Mongolian Altai; b) Semirechye, with a numerical predominance of locations in the Chu-Ili interfluve. Individual signs and their series have been found outside the common region, and from this perspective, the territory of their distribution additionally includes the southern and central regions of Mongolia, Issyk-Kul region, and Eastern Fergana region.

Tamga No. 1 is represented by at least five varieties formed by the addition of lines to the unchanged form of the sign (Fig. 4). The greatest concentration of the main tamga and its varieties occurs in the Issyk-Kul region, Chu-Ili interfluve, and the Ketmen Mountains, that is on the left bank of the Ili River and the right bank of the Chu River up to Issyk-Kul. To the west and south of this

Fig. 4 . Locations of tamga No. 1.

1 – Bololu; 2 – Kochkor; 3 – Akolen; 4 – Akterek; 5 – Akkainar; 6 – Tamgaly; 7 – Chagan; 8 – Ule; 9 – Ulandryk IV; 10 – Tuyakhta; 11 – Tsagaan Salaa; 12 – Koibastau; 13 – Bombogor; 14 – Khurugiyn Uzur; 15 – Baishint.

area, the tamgas have been found only sporadically, and derivative signs have been rare.

To the northeast of Semirechye, in the hypothetical initial habitation area of the owners of tamga No. 1, omega-like petroglyph signs have been repeatedly discovered in the Altai (Chagan, Ule, Tsagaan Salaa, and Koibastau) (Kubarev V.D., Tseveendorj, Jacobson, 2005: App. I, fig. 379; Guneri, 2010: Fig. 2, 1). Its derivative forms (Kubarev V.D., 1987: Fig. 3, pl. LXVII) rarely occur in that region. Tamga No. 1 is a part of two collections of signs. It appears on the bottom of the vessel from burial mound 3 of the Tuyakhta cemetery, and on the memorial stele from Bombogor (Kiselev, 1951: 540–541, pl. LII, 7; Bazylkhan, 2011: Fig. 3). Despite incomplete data, concentrated locations of tamga No. 1 in two areas (the high mountains of the Altai and the Chu-Ili interfluve with the Issyk-Kul region), as well as dispersed areas of this sign, can be clearly visible on the map of the region. The absence of this tamga in the intermediate territory which separates the two areas of concentration (Tarbagatai and Zhetysu Alatau) is notable. This tamga has also been missing from the territory of Central Kazakhstan. The path of the owners of tamga No. 1 from the Altai to the western part of Semirechye and the Issyk-Kul Depression could have passed from the east, through the Ili valley, or the southeast, from the Inner Tian Shan.

Tamga No. 2 does not have any derivative forms (Fig. 5). It is represented by the variants of a snake-like figure rotated at 180°, and three variants of the image of the “head”: a bend, fork, or circle (oval). Different iconographic variants have been found in Mongolia and Semirechye, sometimes together at the same location, as it is the case in Tamgaly or Bichigt Ulaan Khad, examined by G.I. Borovka in 1925 (Mongoliya…, 2017: 67, photo II, 25188, 25189) (Fig. 5, 3 , 8 , 12 ). A striking example is the rock panel in Urkosh III, where at least five images of the tamga-snake and several other signs were drawn over ancient petroglyphs. Medieval inscriptions located nearby, which mention the titles of the Turkic and Uyghur rulers (Tugusheva, Klyashtorny, Kubarev G.V., 2014) make it possible to evaluate the importance of this religious complex and probably important military and political center in the Altai. Tamga No. 2 in the form of petroglyph has not been found in Tuva and the Minusinsk Basin, therefore a silver vessel with two similar signs from the Uybatsky chaatas should be considered as a gift or trophy. Expensive vessels of this type are more typical of the sites of the Turkic culture in the Altai and

Fig. 5 . Locations of tamgas No. 2 and 3.

1 , 2 – Kulzhabasy; 3 – Tamgaly; 4 – Eshkiolmes; 5 – Urkosh III; 6 – Kalbak-Tash I; 7 – Chagan; 8 – Ule; 9 – Ukok; 10 – Barburgazy II;

11 – Ulandryk I; 12 – Bichigt Ulaan Khad; 13 – Del-Ula; 14 – Mukhar.

Tuva (Savinov, 1984: 124–125; Nikolaev, Kubarev G.V., Kustov, 2008: 176–179).

The tamga-snake and the omega-like sign (their areas of distribution generally coincide) often coexist in famous tamga accumulations: twice in the Chu-Ili Mountains, at Tsagaan Salaa IV, and on a stele from Bombogor in Mongolia (cf. Fig. 4 and 5). The tamga-snake has not been found in the Issyk-Kul region, and only one image has been known in the eastern part of Semirechye.

The uniformity of this tamga and the special role it played among other signs of the Turkic period makes it possible to view tamga No. 2 as an emblem of the supratribal (clan or class) or general tribal identity. In this regard, it seems useful to recall the specifics of the use of tamgas among the Kazakhs in the 18th–19th centuries. Thus, the tamga of the Saryuisyn tribe played the role of a supratribal symbol for several branches of the Senior Zhuz ( Dulat , Alban , Suan ), which constituted the core of this union (Rogozhinsky, 2016: 226–229, fig. 1). It is possible that the tamga-snake had a similar meaning in some ethnic and political union of the medieval nomads from the region. Given the uniqueness of the form and special status of tamga No. 2 at the monuments with tamgas, including memorials of the ruling elite of the Eastern Turks (Choiren, Mukhar), it can be linked with clan symbolism of the Ashide , which was reconstructed in the works of S.G. Klyashtorny and Y.A. Zuev (Klyashtorny, 1980: 92–95, fig. 2, 3 ; Zuev, 2002: 85–86), or it can be recognized as a supratribal symbol of a large group of nomads similar to the Tele or Toquz-Oghuz (on these ethnic and political names, see (Tishin, 2014)).

The invariant basis of tamga No. 3 is the letter V; many derivative forms, including an angle with a circle between the rays, which can be considered the main tamga of a large tribal union, was formed from it. In some cases, this tamga occupies a special “honorable” position when it is combined with other signs of the same type or appears in accumulations of different tamgas. The tamgas on the finds from the Altai, including a belt buckle from Barburgazy (Katanda stage) and fasteners for horse fetters from Ulandryk I have been dated (Kubarev G.V., 2005: 97, 137–140, pl. 3, 12 , 13 ; 33, 15 ; 83, 11 , 12 , 13 , 17 ). The area of main tamga No. 3 with its varieties includes two zones of concentration—the high mountains of the Altai and Semirechye, as well as an area of dispersed distribution along the northern boundary of the Gobi, which makes it possible to establish its complete coincidence with the area of tamga No. 2. Notably, tamgas No. 1 and No. 3 have not been found in the Tarbagatai or Issyk-Kul region, although their combination has been discovered in Bololu in the southeast of Fergana, but scholars are not sure that these signs were simultaneous (Tabaldiev et al., 2000: 88, fig. 2).

The abundance of derivative forms of both signs (tamgas No. 1 and No. 3) with incomplete coincidence of their distribution areas may suggest the existence of numerous related subdivisions which were a part of two large independent unions and occupied some common territories (initially the Altai, then the western part of Semirechye) at approximately the same time (simultaneously or sequentially). In the Tian Shan region, tamga No. 3 (when it is possible to assume the simultaneous creation of signs in one accumulation) is repeatedly combined with tamga No. 2, but never with tamga No. 1. In turn, the omega-like tamga is also often depicted together with the tamga-snake and never with tamga No. 3; one exception is a location in Fergana.

The combination of three signs (No. 1–3) occurs only at the sites of Mongolia: among the petroglyphs at Tsagaan Salaa IV in the Mongolian Altai (Kubarev V.D., Tseveendorj, Jacobson, 2005: 235, fig. 379) and on the stele from Bombogor in Central Mongolia. In this accumulation, tamgas No. 1–3 are depicted on the lower part of the stele and form a row, which separates the upper group of signs of the same type (a circle connected with a line with two outgoing arcs), which has been unknown outside of Mongolia, from 14 tamgas of other forms, 12 of which are among those tamgas that are the most common in the Tian Shan region.

According to H. §irin (2016: 371-372), the epitaph on the Bombogor stele, which mentions the Basmyls and Karluks, was devoted to the “princess” (wife or daughterin-law of the Karluk Yabghu), who had the title il bilge and probably originated from the Ashina dynasty of the Turks or from the Yaglakar ruling dynasty of the Uyghurs. However, the monument shows neither signs that can be correlated with the Yaglakar dynasty, nor a tamga in the form of a stylized goat figurine, which was traditionally depicted on the Khagan memorials of the Eastern Turks. It is also unknown whether the female relatives of the Basmyl rulers possessed the high title of il bilge . The question of whether the leader of the Basmyls, who led the anti-Turkic coalition in 742–744, belonged to the dynasty of Ashina cannot be definitively answered on the basis of written sources (Malyavkin, 1989: 171; Kamalov, 2001: 72–73). The content of the runic text on the stele makes it possible to correlate tamgas No. 1–3 and some more signs at the bottom of the stele with the Karluk union or confederation of tribes, which at some point included the Karluks. It can be assumed that tamgas of the same type depicted on the upper part of the stele probably referred to the “forty-tribe Basmyls”. At least four such signs have been found in Gurvan Mandal (near the Bombogor memorial). Two more signs have been discovered in Del Ula; a Chinese inscription dated to 665 was pecked over the tamga (Mert, 2010: Fig. 9, 10; Sukhbaatar, 2015: 97).

The snake-shaped, omega-like, and V-shaped tamgas known from the Altai and Mongolia are generally dated to the period from the second half of the 6th century to mid 8th century. However, tamgas No. 1 and No. 3, found in Semirechye and Issyk-Kul region, which, in our opinion, are associated with the Karluk unit, can hardly be dated to a period earlier than the second half of the 8th century. Such chronology is supported by the combination of these signs with runic inscriptions (twice in Kulzhabasy and many times in the Kochkor Valley), whose appearance on this territory in the 9th– 10th centuries is also associated with the Karluks or other groups of the Altai-Sayan population (Kyzlasov I.L., 2005: 61–62). In addition, a combination of tamga No. 1 and the sign of the “kos alep” type (two parallel inclined lines), which is known as the tamga of the Kypchaks (see Fig 4, 4), has been found in the Akterek Gorge, which was a part of transit mountain valleys of Zhetyzhol (“Seven roads”), connecting the western part of Semirechye with the upper reaches of the Chu and Issyk-Kul region by nomadic routes. Similar tamgas have been also discovered in Kulzhabasy and other locations of the Chu-Ili interfluve, but they are missing from the Issyk-Kul Depression. The simultaneous presence of the Karluks and Kypchaks on the lands of the Western Semirechye and foothills of the Kyrgyz Alatau could have taken place in the second half of the

9th–10th centuries (Gurkin, 2001: 31–33; Ermolenko, Kurmankulov, 2013: 159). Finally, the concentration of these signs near mountain encampments may reflect the exacerbation of “land shortage” and intensification of tribal struggle among the nomads of the Chu-Ili interfluve during the mass migration of the Karluks to the lands of the “people of ten arrows” and the subsequent flourishing of the urban culture in the foothills of the Northern Tian Shan. Obviously, tamgas No. 1–3 in Semirechye should be dated to no earlier than the second half of the 8th century, but rather to the 9th–10th centuries or later.

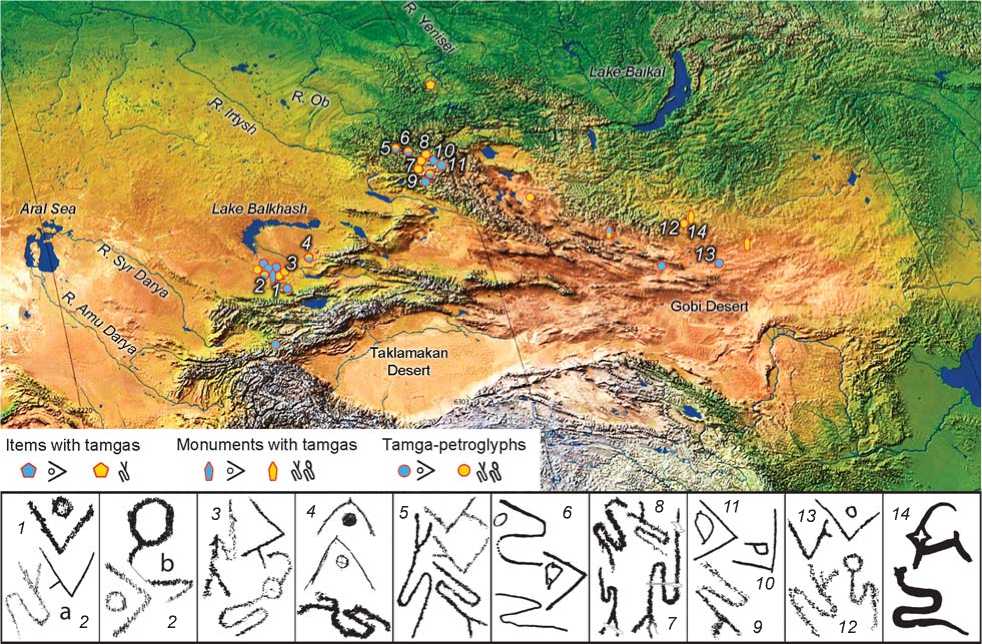

Tamga of the ruling clan of the Karluks

A sign resembling an inverted runic grapheme м (lt), which is present in the tamga accumulation in the valley of the Ashchysu near Tamgaly (Fig. 6, 2 ) belongs to the historical stage of changes in the dominant groups of nomads in Semirechye in the second half of the 8th century. Seven signs were pecked on a vertical rock. They are not contemporaneous: four tamgas, one of

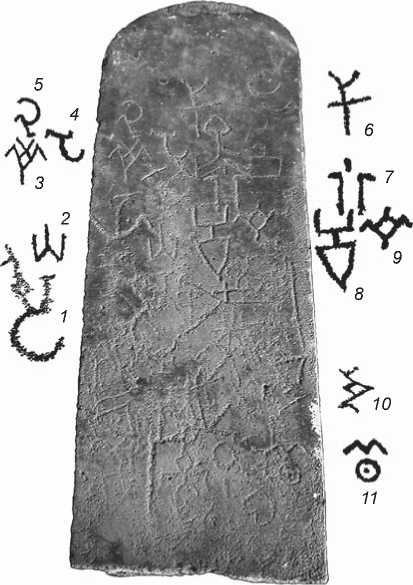

Fig. 6 . Locations of tamgas ( 1–8 ), runic signs ( 9 , 10 ), and tamgas on coins ( 11 – 20 ).

1 – Zhaisan; 2 – Ashchysu; 3 – Tuyakhta; 4 – Chagan; 5 – Taldura; 6 – Yustyd; 7 – Tsagaan Salaa; 8 – Shivet Ulan; 9 – Kalbak-Tash I (XXX);

10 – Kulzhabasy I; 11 – Achiktash; 12 – Kulzhabasy II; 13 – Minusinsk Museum, coin (after (Kyzlasov I.L., 1984)); 14 – 20 – Semirechye, coins (after (Babayarov, Kubatin, 2016)).

which can be identified as the tamga of the Türgeshes, can be considered the earliest. Two signs were pecked separately and probably later, one above the other on the adjacent face of the rock: the lower one in the form of a straight cross, and the upper one in the form of a runic grapheme. The tamga similar to the latter sign is known from the accumulation of signs of the Turkic time in the Zhaisan locality, in the southwest of the Chu-Ili region (Dosymbaeva, 2013: Photo on p. 238). It resembles an inverted Orkhon runic sign (It) or £ (nc) (Fig. 6, 1 ). In both cases, the signs show similarities with letters of the runic script (Fig. 6, 11 , 12 ), but they should not be confused with the brief inscriptions in the form of a single sign (r) found in Semirechye and Altai (Fig. 6, 9 , 10 ).

Both heraldic signs can be identified using numismatic evidence from Semirechye. Already in 1989, on the basis of materials from the fortified settlement of Krasnaya Rechka, the numismatist V.N. Nastich distinguished a coin type with the Sogdian legend “Arslan Kul-Irkin” and two tamgas, “the first of which is in the form of an onion arc with an offshoot inside”, and the second was identical in its shape to the tamga from Ashchysu (Fig. 6, 20 ). Nastich connected this coin issue and coins of another type with the “dynasty (?) of the Arslanids— certain ‘intermediaries’ between the Türgesh rulers and the Kara-Khanids, who replaced them in the 10th century in Semirechye” (1989: 117). To date, several types of coins (Fig. 6, 14–19 ) with the tamga in the form of the runic sign (numismatists correlate it to the grapheme r) as an additional sign in the dynastic emblem of the Türgeshes have been collected at the fortified settlements of the Chuy and Talas valleys. There is a discussion about the dating and attribution of these coin issues (Kamyshev, 2002: 63–64; Koshevar, 2010: 20–22, fig. 4, 5; Babayarov, Kubatin, 2016: 89–93, 97). The coins were found in 2006 at Ak-Beshim (Suyab) with the legend “fan of the Lord Türgesh Khagan” on the obverse, and the dynastic emblem on the reverse, covered by an additional tamga (Fig. 6, 16 , 17 ), which A.M. Kamyshev called “a clan sign of the Karluks” (2008: 18–19, photo 6). This sign is identical to the tamga from Ashchysu, but has an additional point between the left and central lines. Finally, the numismatic finds from the fortified settlement of Shish Tube (Nuzket) in the Chuy Valley has recently made it possible to identify the coins of the Karluks’ own minting, based on the reading of the legend, “coin of the Lord Khagan of the Karluks” by P.B. Lurie (2010: 280–282, fig. 1, 1 , 2 ).

On the coins of this type, the tamga is represented in the form of an “onion arc” similar to the Arslanid coins, and an additional tamga has the form of a runic sign (Fig. 6, 19), similar to the petroglyph from Zhaisan. According to Lurie, the issue of these rare coins was shortlived and could “relate to any time between 766 and the mid 10th century”; however, “the Sogdian transcription of the ethnonym Kar(a)luk on the coin is earlier than the one which appears on the Karabalgasun inscription” (Ibid.: 282), and the preferrable period of the coin issue is the second half of the 8th–mid 9th century (Babayarov, Kubatin, 2016: 92–93). Notably, petroglyphs-signs that appear to be the dynastic emblems of the ruling clan of the Karluks are very rare in Semirechye as compared to other tamgas, which can be identified as clan and tribal signs of the Karluk confederation units.

Outside Semirechye, tamga-petroglyphs in the form of runic graphemes or have been found at Tsagaan Salaa I in Mongolia (Fig. 6, 7 ), and at the origins of the Chuy River in the adjacent valleys of the Taldura* (Kubarev G.V., 2017: 344, fig. 1) and Chagan in the Russian Altai (see Fig. 6, 4 , 5 ). The latter location is especially important, since similar signs discovered by D.V. Cheremisin were combined there with other items: two tamgas were depicted together with expressive engravings of the Turkic time (cataphract horsemen, etc.); another sign was represented on a rock next to the tamga-snake and other petroglyphs located in the area of the concentration of the medieval sites, burial mounds, and ritual enclosures with steles and rows of balbals.

Two images on silver vessels found in the Altai (in mound 3 at the Tuyakhta cemetery, and in a ritual enclosure with a stele at the Yustyd XII cemetery (see Fig. 6, 3 , 6 )) are pertinent to our discussion. A tamga-like goat figurine is represented on the central part of the bottom of the vessel from Yustyd XII; another tamga “in the form of the letter (W) of the Orkhon-Yenisei alphabet is represented on the tray” (Kubarev V.D., 1984: 73, fig. 12, 1 ). With its wide base down, it resembles the grapheme with diverging baselines. This sign could be perceived differently only in an inverted position of the vessel. In this form, the tamga shows greatest similarity to the petroglyphs from Taldura, Chagan, and Zhaisan, and to the sign on the coins of “Lord Khagan of the Karluks”. If the position of the heraldic sign was important, the tamgas represented on the vertical surfaces of immovable items with limited frontal access, that is, rocks and monuments are needed for establishing its canonical appearance.

I.L. Kyzlasov gave a detailed description of the signs on the vessel from Tuyakhta (2000a: 83–85, 88–90, fig. 1). A drawing of the engraving, made by S.V. Kiselev in 1935, is also known (Vasiliev, 2013: 33–34). At the present time, when it is possible to see the monument on high-quality photographs , the conclusions of our predecessors can be supplemented with additional arguments.

We should point to the compositional and semantic connection of the engravings placed on the flat bottom and inclined rim of the tray from Tuyakhta. A runic inscription covers about a third of the rim; a large tamga occupies the main space of the bottom and is turned with its base towards the inscription. This series of engravings can be considered synchronous. The same tamga appears at Bichigt Ulaan Khad, possibly in the accumulation of signs at Kalbak-Tash I, and on the bottom of a vessel from the Kopyonsky chaatas (Evtyukhova, Kiselev, 1940: Pl. III, b). Later, a large omega-like tamga was engraved over the first sign, and two smaller signs of smaller sizes (a variety of the bitriangular tamga and tamga No. 3 in one of its variants) were engraved on the narrow rim. The fourth sign is partially covered with a spot of paint with the museum code; judging by the drawing by Kiselev, there may be two more signs under the spot. Finally, the fifth sign was inscribed between the omega-like tamga and signs on the tray, which in its shape looks similar to the sign on the vessel from Yustyd XII. Generally, the late group of engravings on the vessel can be viewed as a separate accumulation of identifying signs belonging to the representatives of different clans (?), which could have participated in an important collective action (concluding an alliance, funeral feast, etc.). All distinguishable signs of this series belong to the most common signs in the eastern part of the Central Asia, but numerically predominant in the Altai and Semirechye. We should emphasize that the dominant role in this accumulation is played by the tamgas placed in the center of the pictorial field, that is, the omega-like tamga and sign of some privileged clan, identified by the numismatic evidence from Semirechye as the emblem belonging to the rulers of the Karluks in the second half of the 8th–9th centuries.

The dynastic Karluk tamga, as with tamga No. 2 or the emblem of the Yaglakar clan, is rare and is characterized by the stability of its form. In the Altai, such a tamga has also been found at Tsagaan Salaa I; the sign looks similar to the tamgas on the Arslanid coins, but has two points, and not one as is the case with the additional tamga on the coins from the fortified settlement of Ak-Beshim. Also noteworthy is a little-known coin kept in the Minusinsk Local Lore Museum, which has three signs scratched on the reverse and a tamga-like figure (Kyzlasov I.L., 1984: 94, 96, fig. 3) similar to the Altai petroglyphs from Chagan and Taldura. Finally, the representation of the tamga of the Karluks appears on the stele at the Shivet Ulan complex in the Khangai at a considerable distance from the Altai subarea of sign distribution (see Fig. 6, 8 ).

Active study of the memorial complex of Shivet Ulan, including the stele with tamgas, has been recently resumed, but the date and attribution of the monument has not been definitively established (Kidirali, Babayar, 2015). Without going into discussion about the origin of this unique accumulation of signs, we should limit ourselves to pointing to the obvious facts*, associated with the representation of the Karluk tamga.

In its present form, the stele with tamgas as a small architectural structure at a memorial complex is not a selfsufficient monument in its own right; at some point it was subjected to reconstruction according to the principle of palimpsests: 1) abrasive treatment of the surface of the solid rock was done selectively (petroglyphs are still visible under the tamgas; some signs were intentionally removed, but not completely erased); 2) the upper part of the stele, the most important in semantic terms, was carefully polished for secondary (?) application of representations or text, but remained empty. The accumulation of signs consists of at least two groups of multisymbolic images created at different times: the tamgas are different in size and execution technique; later signs are superimposed on earlier signs and traces of crude renewal of the latter are visible; compositional consistency of the group of early signs was disrupted by the addition of larger, later figures. Finally, the signs of the early and later groups belong to different areas of the predominant distribution and presumably of different unions of the medieval nomads of Mongolia and Southern Siberia.

Two signs of the main tamga of the Uyghurs and three signs of the Yaglakar clan (two in canonical form as on the stele from Mogoyn Shine Usu, and one with an additional element) stand out from among the early engravings. Four of these five signs occupy the upper level (Fig. 7, 3–5 , 8 , 10 ). The tamga of the dynastic clan of the Karluks (Fig. 7, 2 ), similar to the signs at Tsagaan Salaa, Ashchysu, and on the Arslanid coins, is located closer to the middle part of the obelisk. The later signs under the Karluk tamga include a large representation in the form of a sickle with a handle and an additional figure similar to a key (Fig. 7, 1 ). This sign is commonly found among the petroglyphs of Mongolia and, most importantly, appears at commemorative structures belonging to the ruling elite of the Uygur Kaganate in the initial period of its history (Mogoyn Shine Usu) and its final stage (Sudzhi). The area of this tamga does not extend beyond Mongolia; this sign is most likely associated with one of the influential subdivisions of the Toquz-Oghuz, although the exact attribution of the tamga remains problematic.

Seven to eight signs distinguished by the depth of pecking and their large scale constitute the central axis of the tamga composition. Almost all these tamgas (Fig. 7, 6 , 7 , 9 ) commonly appear among the petroglyphs of Tuva and the Minusinsk Basin, at the memorials of

Fig. 7 . Stele with tamgas from the Shivat Ulan complex. Photo by N. Bazylkhan, drawing by A.E. Rogozhinsky.

Elegest (E-10, 52, 53, 59, etc.) and Eerbek (E-147, 149), on the rocks of Maly Bayankol, Ust-Tuba, and Turan (Repertoire…, 1995: Pl. 50, 29a, 2 , 30, 2 , pl. 52, 36, 2 , 3 , etc; Belikova, 2014: Fig. 23). Tamgas of this group in Mongolia are rare (Mert, 2009: 11). The main area of the signs that prevail on the stele is associated with the territory on the upper and middle reaches of the Yenisei River. The tamga in the form of a circle with a point in the center and connected arcs above it (Fig. 7, 11 ) is particularly notable. The shape of this sign is identical with the tamga found by A.V. Adrianov on the left bank of the Belui Iyus. Later, I.L. Kyzlasov established the area of this tamga as the northern part of Khakassia (2000b: 72–73, fig. 1, 5 ).

Identification of some of the signs on the stele makes it possible to distinguish two stages in the emergence of tamga accumulations: the early stage, when the owners of the signs of the above Toquz-Oghuz and Karluk subdivisions had approximately equal status, and later, when the tamgas of the incoming groups from Tuva and Khakassia started to occupy the dominant position. The addition of new signs to the stele can be confidently associated with the collapse of the Uyghur State and thus must have happened not earlier than 840. The period of the existence of the Uyghur Khaganate (744–840) as a probable time for the creation of the early group of signs should be excluded considering the position of the Yaglakar tamga in the same row with the emblem of the ruling clan of the Karluks. Apparently, the early stage of the formation of this accumulation goes back to the previous period when the leaders of the Toquz-Oghuz and Karluks recognized the political superiority of the Eastern Turks whose dynastic sign could have occupied the upper area of the stele before its “restoration”. An indirect indication of the particularly high political status of the unknown commemorated person is the presence of emblems belonging to the ruling clans which governed two major unions of nomads of Central Asia of that period, on the monument.

Conclusions

The increased volume of identity signs belonging to the medieval nomads from Central Asia, and their specialized study make it possible to use this source in historical research along with other sources traditionally used. Comparative analysis of such signs from the Altai and Semirechye has shown a close relationship between the population of two historical and cultural areas of the region, and has made it possible to establish the areas of

the most common signs and movement vectors of their owners. Groups of tamgas of the same type (tamgas No. 1 and 3) have been identified. They are distinguished by a variety of forms and mark the presence of related units in both territories at the same period of time. It may be assumed that tamga No. 2 had the status of a sign designating supratribal identity. Its uniform shape was preserved in various contexts. A group of signs that served as markers of ethnic and political identity of the ruling clans of the Uyghurs and Karluks during the emergence of statehood in the 8th–9th centuries has been identified.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Project URN: БР 05236565).