The tiger-dog and its semantics in the Nanai Shamanic sculpture: cultural and cognitive aspects

Автор: Maltseva O.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article describes the Nanai shamanic set, combining two images—a dog and a tiger. The Nanai shamanic sculpture is viewed as a phenomenon reflecting both the subjective and the objective reality constructed by traditional cultural practices. Parallels with Siberian and Pacific cultures reveal the significance of the domestic animal and the wild predator for the people of the Lower Amur. Using folkloric and lexical data, findings of field studies, and ethnographic evidence, folk images of the dog and the tiger are reconstructed. Viewing the problem in the context of collective knowledge about the world reveals the archetypical and modified layers in the image’s construction. The idea of the dog, typical of all the peoples of Siberia and the Russian Far East, is that of a draft animal, assistant, sacrifice, and guide to the afterworld. Its image in the Nanai shamanic sculpture was meant to enhance the power of the spirit. It was often combined with the image of the tiger, personifying shaman’s power and the progenitors. The analysis of the terminology relating to the tiger attests to the Southeast Asian roots of its cult. The tiger semantics in the Nanai culture resulted from a blend of Tungus, Paleoasiatic, and Manchu (Chinese) elements. These images were used by shamans not only as assistants in “capturing” spirits and holding them in “detention”, but also as a means of communicating with the world of spirits.

Ritual sculpture, Nanai people, dog, tiger, semantic field, shaman

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146260

IDR: 145146260 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2021.49.2.125-133

Текст научной статьи The tiger-dog and its semantics in the Nanai Shamanic sculpture: cultural and cognitive aspects

Shamanic sculpture of the Nanai people is an understudied cultural phenomenon. Its meanings reflect both individual and collective knowledge of the world; and the semantic field of this experience determined the cultural space of the Lower Amur society, comprising many components and manifesting features typical of both egalitarian and stratified communities with animistic views and sophisticated religious cults. The area of this cultural phenomenon includes Siberia with the lifestyle of taiga hunters and reindeer breeders, the Pacific coast where the population practiced sea animal hunting, and some regions of East Asia with agricultural and trade traditions of the population with whom the Amur Valley inhabitants maintained close cultural ties and practiced trade exchange. Studying the examples of the combined cultural elements of the “north” and “south” in the Amur Valley makes it possible to see the cultural syncretization in a wider context and to identify not only its cultural and historical aspects, but also the cognitive factors which gave rise to it (Artemieva, 1999; Campbell, 2002: 90–95; Flier, 2012; Geertz, 1973).

This article analyzes some syncretic images from the ritual realm of the Nanai people, and creates a collective mental portrait of the carriers of traditional culture in terms of its multicomponent composition. The difficulty of studying the ritual sculpture of the Nanai

Stylistically similar sets of wooden figurines have also been known from other locations in the Lower Amur region, which suggests the transmission of shamanic knowledge through intercultural communication (Kubanova, 1992). According to a survey among the indigenous population in these areas, such connection emerged during funerary rites. For example, among the Gorin Nanai people, there were no powerful shamans; therefore, for the final stage of the funerary rite—the ceremony of sending the soul of the deceased to the afterworld—they invited the shamans from the Nanai people living directly in the Amur Valley. It was believed that these shamans knew the structure of the world and funeral and commemorative customs of the majority of the Amur clans (FMA, village of Kondon, I.K., L.F., and V.V. Samar, November 22–23, 1998). In this way, contacts between the population of the Amur and Gorin valleys were maintained. The established tradition of the shaman’s invitation also contributed to the emergence of a universal shamanic set “for all occasions”. Although such sets (consisting of wooden figurines) belonging to the shamans of various categories had a common basis, they also had their own distinctive features (Smolyak, 1991: 54–56). In the process of his formation, the shaman not only adopted the main methods of entering into contact with spirits from his mentor, but also often established his own line of communication with the invisible world through improvisations, which resulted in appearance of syncretic imagery (Ibid.: 132–154) (FMA, village of Naikhin, R.A. Beldy, August 28, 2011). To interpret such imagery, we should consider the hypothesis that the wooden figurines that were a part of the ritual sets, were not only the receptacles of the spirits subordinate to the shaman. In order to “decipher” each image, it is desirable to analyze not only its semantics, but also the nature of its connection with other images in the set.

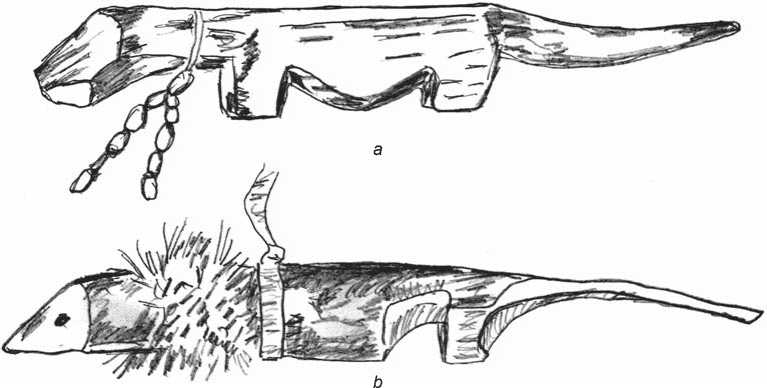

Some sets retained their importance also in the Soviet period. According to the journal materials of V.A. Timokhin, in the 1970s, among the Nanai people of the Khabarovsk Territory, there still were shamans who continued healing practices using wooden sculptures called sewens . The records of Timokhin, among the wooden containers of diseases, mentioned sewen Buchile , which, together with “two men” and “a dog” ( indavla/ endaula ), was used as a remedy (Maltseva, 2008: 167). Approximately twenty years later, a similar selection of wooden items from the shaman set was described by T.A. Kubanova, relying on information from the Kevur group of the Kondon Nanai people, who adhered to the same shamanic traditions as the Amur Nanai people. She observed that the cultic composition of Buchile was formed according to the principle of dichotomy, uniting the figures of ancestors—a tiger and tigress (the female Buchile is smaller in size)—depicted in the sitting position, which denoted a male and female Buchile . Each of these Buchile had its own groups of sewens : a set of the “ancestor-tiger” included sewens rendering the images of a tiger ( Mokhe ) and tigress ( Khapo ); in a pair, they are called indavla totkorpani (“the dog that hits the target”); and a set of the “ancestor tigress” included two flattened figures representing her children—tiger cubs ( sangarav ) (Fig. 1) (Kubanova, 1992: 33–43).

In order to analyze the stylized image with the double name, which was a part of this set and conveyed

Fig. 1. Ritual sculpture ( sewens ) of the Nanai people, the Buchile set.

a – male Buchile , “ancestor-tiger”, the main assistant of the shaman (Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East SB RAS (MHCPSFE SB RAS), No. KP 761 osn.); b – Mokhe ( Mokha ), assistant to male Buchile , stylized image of tiger (MHCPSFE SB RAS, No. KP 2088 osn.); c – Khapo , assistant to male Buchile , stylized image of tigress (MHCPSFE SB RAS, No. KP 763 osn.); d – female Buchile , “ancestor-tigress”, assistant to the shaman (MHCPSFE SB RAS, No. KP 760 osn.); e – sangarav , “children” of the female Buchile , in the form of tiger cubs (MHCPSFE SB RAS, No. KP 1891, 1892 osn.). Sewens Mokhe ( Mokha ) and Khapo form a separate group indawla totkorpani ‘the dog that hits the target’.

the meaning of a dog and a tiger, we need to trace the development of its name, content, and form in the historical and cognitive context of the traditional culture of the Lower Amur region.

Dogs in the Amur Valley— from real to symbolic animals

The worldview of the Nanai shamans reflected the natural conditions in which the Amur fishermen and hunters lived. The host of their spirits included the images of wild and domesticated animals inhabiting Siberia and the Far

East. These regions are located in the taiga zone, where economic models associated with hunting, fishing, and reindeer breeding evolved. Already in the early stages of human history, the inhabitants of this northern part of Asia could not live without dogs, which helped them in hunting, grazing and pasturing deer, and transporting belongings and people (Losey et al., 2018). In Northern Eurasia, two large areas can be distinguished where the use of dogs had its own specific features. In central Siberian taiga and tundra zones, where relationship between people and deer had a firm basis in economic and cultural areas, dogs were used as sheepdogs. On the Pacific coast, traditions of breeding sled dogs emerged, which were reflected in the vocabulary of the Paleoasiatic peoples. The Nivkhs have a corpus of words denoting the functions of dogs and their position in the harness (‘sled dog’ – if қan, ‘dog following the leader in sled harness’ – latrat, ‘first dog in sled harness’ – nuɧis, etc.) (Savelieva, Taksami, 1970: 140, 157, 214).

The attitude to dogs among the Tungus-Manchu peoples of the Amur Valley was influenced by the Paleoasiatic and Tungus (Siberian) forms of economic activities and beliefs. The dog has become a multivalued figure in the life of the local community, and this role became reflected in folklore and the sacred domain. The dog’s image absorbed many of its original features as transportation animal, sacrifice, assistant, and equivalent of man. The vocabulary of the Nanai people contains the name of sled dog – khaliachiri inda ; but more words are associated with designation of dogs depending on their color, working qualities, and position in the pack (for example, ‘gray dog’ – kurien , ‘black dog with a white stripe on the forehead’ – chokoan , ‘several months old puppy’ – keicheen , ‘leading dog’ – mioriamdi , ‘female dog’ – vechen ) (Onenko, 1980: 94, 234, 237, 262, 448). Folklore shows the attitude to the dog as a thinking and self-motivating being. In the Nanai fairytales ningman , one can distinguish the plots where the main character in the form of a dog becomes a relative of people and is endowed with human rights (Nanaiskiy folklor…, 1996: 174–183, 290–300; Sem, 2001). Such ideas have also found their place in ethical norms. Representatives of all Nanai families observed the ban on killing a dog. Taking care of dogs, their treatment, and, in the event of death, funeral with honors—all this formed the basis for the tradition of honoring dogs as human partners among the hunting peoples of the Amur Valley (Schrenck, 1899: 185–186; Sternberg, 1933: 500).

The perception of a four-legged helper as a sacrificial animal and contactee with spiritual beings has a more ancient subtext as compared to the one described above, which is confirmed by the Neolithic evidence found in Siberia (Losey et al., 2011). The Nivkhs, living next to the Ulchi and Nanai people, sacrificed dogs to appease the gods and make it easier for the deceased to travel to Mlyvo (the afterworld) (Sternberg, 1933: 299–328). Ritual killing of dogs in the name of supreme powers was practiced among a number of semi-sedentary peoples inhabiting the northern part of the Pacific coast (Sokolova, 1998: 261–262).

In Siberia and Pacific coast, the connection of dog with the hypostases of the mythical universe is most clearly manifested in burial complexes and funerary rites. In one of the mythological tales of the Yukaghirs, a dog acts as a guard of the road of the dead, judge and master of human destinies in the afterworld (Folklor…, 2005: 305). According to the Nanai beliefs about buni (afterlife), a dog was the carrier of the soul of the deceased:

several harnessed dogs took the soul to another world (Shimkevich, 1896: 18).

A dog could be a counterpart of a wild animal. The dog-wolf relationship was perceived to be on the same conceptual plane among the peoples of Siberia with the nomadic type of economy. The following configuration of the animal autonomy emerged there in the form of a conventional triangle: deer was in one corner, elkhound in another corner, and wolf was in the third corner (Losey et al., 2011; Stepanoff et al., 2017). In the sacred realm, wolf and dog sometimes replaced each other; their essences were related to patronage of reindeer herd or to hunting (Ivanov, 1970: 34, 36, 88–90; Baldick, 2012: 147–148).

The worldview of the Tungus reindeer breeders has received a new content during their migration to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. The changes affected primarily the hierarchy of spirits that had their representations in the animal environment. The wolf has practically lost its sacred essence in the beliefs of the groups inhabiting the Amur Valley. There are several explanations for this. Pack-hunting is difficult in rough taiga terrain, which was sometimes flooded during the overflow of the rivers, and wolfs might face stronger competitors, such as bear and tiger (Cherenkov, Poyarkov, 2003: 7–33). In the past, there were isolated cases of capturing wolves in the lower reaches of the Amur River. The wolf was even a totem in some of the Nivkh clans; but in spiritual terms, the wild relative of the dog did not replace it (Priamurye…, 1909: 268; Sternberg, 1933: 304–305). The connection between the bear and dog as a sacrifice was expressed in the traditional consciousness of the population living in this part of the Amur region. Notably, the Gorin Nanai people had a tradition of leading a bear around the village, with harness khala put on it, essentially treating it like a riding animal. It can be assumed that in this case the bear performed the function of a dog (Samar E.D., 2003: 36). The Nanai people from the Lower Amur believed that the soul of the deceased was brought to the next world by a train of dogs headed by a bear (Lipsky, 1925: 47 (XLII); Smolyak, 1976: 131). Strengthening of the bond between the dog and bear in conservative rites serves as a proof that the Tungus-Manchu groups adopted the Paleoasiatic traditions.

In the shamanic iconography of the Nanai people, dog and bear were not paired. The image of a dog denoted the quality and property of connections between the objects of the spiritual world. From the host of shamanic spirits represented in sculptural form, one can distinguish the images of the mythical dog Vanko—a companion of an evil spirit or shaman and executor of his will, and the ‘dog’s head’ ingda delini, guarding the souls of the dead, who have no opportunity to be reborn (Onenko, 1980: 90; Smolyak, 1991: 199–200). In the Buchile set, which included the sewens Khapo and Mokhe, the dog expressed the nature of their relationship; it united the sewens into one group. To understand this pattern, one needs to proceed from the perception of dogs, which emerged among the peoples with a fishing and hunting lifestyle. The evidence relating to the Nivkhs and some peoples of Siberia makes it possible to identify several interrelated spiritual roles of the dog: “sacrifice”, “receptacle of the soul of the deceased”, and “guide to the afterworld” (Samar A.P., 2011: 125). Under these guises, dogs appeared also in the shamanic worldview. At the same time, we cannot rule out the overlapping of various symbolic functions of the dog, which emerged during the borrowings and transformations. Taking into account the essence of shamanic spirits, closely related to nature (terrain, flora and fauna, climatic conditions, etc.), and the second name of the Mokhe-Khapo group – ‘the dog that hits the target’, it can be assumed that reference to the dog is intended to emphasize the power of the spirits’ influence. In this case, its initial function in human life as assistant and guard was taken as a basis (Sternberg, 1933: 495). The reflection of the utilitarian meaning of dogs in the sacred realm makes it possible to consider the sets of ritual sculptures as a kind of language. The double name, which includes the dog, serves as an emphatic construction, emphasizing strength and speed of the spirits “subordinate” to the shaman.

Adaptation of tiger image among taiga hunters and fishermen

The use of the image of a tiger among the Lower Amur peoples involves several semantic variations. Each of these reflects the evolution not only of concepts, but also of the shamanic complex as a whole. The conceptual model associated with the tiger image is based on the attitude towards the real animal. The indigenous population of the Amur Valley came into direct contact with tigers; therefore, many ideas about tigers resulted from observing them. For hunters, tigers were dangerous competitors; tigers often attacked unprotected camps or fishing groups, and forced them to look for new places to stay. The local population, which perceived tigers as carriers of mystical qualities, considered it to be one of the first ancestors. Such Nanai clans as the Samar, Beldy, Odzyal, and Aktanko traced their origin to the marriage of woman and tiger (Lopatin, 1922: 206–209; Nanaiskiy folklor…, 1996: 405–407; Samar E.D., 2003: 9–26). The tiger cult among the Tungus-speaking peoples, as was observed by Shirokogoroff, manifests the effect of various cultural systems (1935: 70–185). The most striking evidence of mixed heterogeneous layers in the worldview is the “tiger” terminology, applied mainly to the sacred realm. In this regard, it is interesting to compare the tiger and the bear as the main actors of ecological and social communication in the Amur Valley.

In the peoples of the Lower Amur region, the conceptual framework associated with bears is more detailed than with tigers. In the Nanai language, the tiger has received the compound name puren ambani ; panther and leopard have the names amban edeni or yarga . Previously, the image of a leopard was called mari , while that of tiger was called yarga or ambani sewen (Onenko, 1980: 36, 258, 543). The lexeme amban ( ambani , ambasani ), belonging to the group of names of feline predators, raises some questions regarding its etymology, and also its usage with several meanings. In the Nanai environment, it denoted an evil spirit, as well as tiger the animal. Modern Nanai informants still link together two sememes of the one word, which designates the properties of immaterial entity and material object in the guise of the animal. The tiger has become the embodiment of an evil spirit and a punishing, destructive, and irresistible force. In the late 1990s, in the Museum of Local History in Komsomolsk-on-Amur, the author of this article observed that some visitors from the indigenous population were afraid not only to pass by a stuffed tiger, but even to look at it. The visitors to the museum assured me that they were experiencing a superstitious fear from seeing the beast. Such a response testifies to preservation of the original attitude towards this predator in the depths of the Nanai consciousness. According to the information recorded in the Ulchsky District of the Khabarovsk Territory, the indigenous population of the Amur Valley does not always associate the beliefs about the tiger as the embodiment of deceit, wisdom, and clan power, with the real animal. Talking about receiving her gift in a dream, the Ulchi shaman Sofya Angi-Valdyu mentioned that for several nights her late father appeared to her in the guise of a tiger and each time offered her something item of shaman’s equipment. On this occasion, she embroidered a picture of her ancestor-tiger, which looked most similar to a lion. As it turned out, the shaman submitted the screen image of the animal, which she associated with a tiger, since she had never seen a living tiger (FMA, village of Bulava, July 21, 1996).

Notably, transmission of animal imagery and interpretation of their qualities depend mostly on perception and knowledge of the world, fixed in the vocabulary. Since the 1930s, a pidgin derived from the literary Nanai and Russian languages played an important role in transmitting knowledge among the Nanai people, similarly to the majority of the peoples inhabiting the Amur Valley (Perekhvalskaya, 2008; Mamontova, 2015). The adopted literary vocabulary did not contain a set of the concepts related to the construction of the mental world, in particular, to the shamanic iconography. Using the introduced linguistic standards, new worldview complexes have emerged, in which the features of physical nature were combined with properties of the spiritual objects.

Viewing the problem through the lens of linguistic metamorphosis makes it possible to focus on the amba / ambani concept. While studying the rituals of the Nanai shamans, Bulgakova observed that their spirits ( sewens ) were not the embodiment of the subjects taken from the material world. Sewens were immaterial entities; to become stronger, they only adopted the features of animals (it could have been a combination of features from various species). They were opposed by amba — uncontrollable spirits who were not subordinate to the shaman (Bulgakova, 2016: 290–291). Shirokogoroff linked the appearance of the word amban in the Tungusspeaking environment with the Manchu and Chinese influence. This word was used to denote high officials, for whom the use of tiger skins was a sign of prestige (Shirokogoroff, 1935: 82). The indigenous inhabitants of the Amur Valley, who maintained close contacts with the Manchus, interpreted the use of tiger skins by the highest dignitaries of the Manchu court in their own way. The prohibition on hunting tigers has acquired totemic status among the dwellers of this region. The emerging tiger cult had similarities to, and some differences from, the bear cult. In both cases, some designations of the animals reflect a related use of names. For example, the Nanai people perceived the bear as an ancestor, and called it mapa (‘grandfather’, ‘old man’) (Onenko, 1980: 258). Their vocabulary also reflects the age of the bear: they call a bear-cub of 7–8 months of age sirion , one-year-old bear chairo , 2–3-year-old bear khoer , and 3–4-year-old bear puer (Ibid.: 340, 367, 463, 497). The relation to this carnivore as a blood relative is conveyed by the word agdima , meaning both the eldest of the brothers and a 5–6-year-old bear (Ibid.: 27).

The representatives of the Nanai clans that believe they have originated from the tiger sometimes called it daka (‘father-in-law’) (Ibid.: 134). However, traces of the potestar organization have survived in the “tiger” terminology and the tradition of endowing the feline predator with the features of a taiga deity. Almost no peoples of the Amur region have practiced the ritual killing of this animal; and if it was killed for attacking a man, a symbolic trial was organized on this occasion, with participation of a zangin (tribal judge). This judge received a silk robe and a cauldron for his work, which served as a sign of reconciliation between the two parties—the “clan of the tiger” and that of the “man” (Smolyak, 1976: 151–152; Sternberg, 1933: 501–502). If a dead tiger was found in the forest, it was buried clothed in human outfit; depending on the season, it was dressed in winter or summer pants, khalat, footwear, and hat (Istoriya…, 2001: 92–93). The image of tiger entered the shamanic pantheon of spirits with a status of taiga deity. In the hierarchy of entities with zoomorphic features, the sewens with tiger qualities had the highest rank, as those close to the shaman. The problem is the interpretation of tiger images embodied in sculptures. Their origin points to borrowings from the religious and philosophical teaching of Buddhism and agricultural complexes. According to Shirokogoroff, the pantheon of spirits of the Tunguses emerged in the process of reworking the Manchu system of the spiritual world based on a number of Chinese cults (1935: 108–164). Among the spirits, the mafa group stands out, which had several interpretations. The spirits with the name mafa, which means ‘noble man’, ‘old man’, were considered the ancestors of the Manchus. According to Buddhist teachings, they descended from ancient animals and were neither benevolent nor harmful, but could cause illness and misfortune. In the Manchu complex, the word mafa also denoted various borrowed spirits with whom it was desirable to maintain good relations (Ibid.: 143, 145, 151, 158, 234–238). Among the Nanai and Tungus peoples, the word mapa/mafa with the meaning of “old man” referred to the patron spirits of places, and served as allegorical designation of bear (Lopatin, 1922: 206; Onenko, 1980: 258). It can be assumed that the name of sewen Mokhe/ Mokha in the Nanai shamanic complex goes back to the word mapa/mafa. When this name entered shamanic ritual usage, it was phonetically changed and began to be used for denoting the status of a spiritual entity with punishing, destructive power, and the personification of a number of diseases. The etymology of the word khapo, meaning a sewen with protective function, which opposes sewen Mokhe with destructive, punishing power, causes many questions. The Nanai vocabulary does not contain words with the same root or a similar meaning, which suggests that it was borrowed from another language. In the works of P.P. Shimkevich, the sewen that symbolically expresses patronage and protection is called khafani. Its appearance may be associated with the dissimilation of consonants in the word mafani, and formation of words denoting the opposite hypostases in the configuration of the cultic realm (like mukhani/khafani; mokhe/khapo). It is also possible that the word khapo(ni) was formed as a result of adapting the name Dzhafan mafa—the patron spirit of house and estate among the Manchus—in the conglomerate of the Nanai shamanic spirits (Shimkevich, 1896: 52).

When considering the semantics of sculptures rendering the image of a feline predator, small discrepancies in conveying similar images in different parts of the Lower Amur region have been identified. The evidence gathered by several generations of scholars contains the following combinations of names: yarga , khafu yarga , ambanso , ambanso mukhani , ambanso seoni , mocha , and khapo (Kubanova, 1992: 37–43; Lopatin, 1922: 224–228; Shimkevich, 1896: App. 1; Baldick, 2012: 143–144). These should be interpreted not only in the light of shamanic “improvisation”, when the shaman himself personified the spirit and determined

Fig. 2 . Representations of a wolf and a dog.

a – wolf- syadei , Nenets people (Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) of the RAS, coll. 2427-8); b – dog, Sakhalin Evenks (Russian Museum of Ethnography, coll. 6936-122).

its position in the hierarchy of invisible entities. It is also important to take into consideration the natural, social, and cultural contexts. In the southern part of the Nanai habitation area, which coincides with the ranges of the Amur tiger and the Far Eastern leopard, the attitude towards real predators was reflected in the shamanic worldview in the form of the supposed links between the tiger and leopard. The evidence discovered in these areas by the scholars in the late 19th to 20th centuries contains numerous representations of cultic images with feline features, which occupied various positions in the hierarchical system of spirits (Lopatin, 1922: 225–228; Shimkevich, 1896: 40–45). A.V. Smolyak gave an example of subordination, in which the assistants of the amban sewen (in the form of a tiger) were sewens of a lower rank— yarga (of a spotted leopard) (1991: 71). In the northern regions of the Nanai people (for example, the Gorin Nanai) territory, the “tiger-leopard” group of the shaman’s set did not have such details. Notably, the worldview of the indigenous population inhabiting the Lower Amur region was enriched with new ideas under the influence of trade and family ties with the Manchus; up to the early 20th century, the posts of the Manchu officials could have been the centers for spreading state shamanism and Buddhist philosophy (Schrenck, 1883: Vol. 1, p. 53–74).

Outside the Lower Amur region, three-dimensional wooden representations, similar in style to the Amur sculptures, have been found in some parts of Siberia and Sakhalin. These are usually figurines with the horizontally elongated torsos and muzzles indicated by several cuts. Among the Nenets people, such small-scale sculpture serves as receptacle of the spirit of the wolf—syadei. Among the Sakhalin Evenks, a figurine with similar features conveys the image of a dog, and was used in the past as a toy (Fig. 2) (Ivanov, 1970: 89, 250). This is a widespread sculptural form, whose conventionality made it possible to fill it with different content in various regions of Siberia and the Far East. The meanings of this stylized image in various geographical locations reflect the distinctiveness of the natural environment of the nomadic community living in Northern Eurasia. In the culture of the reindeer breeders of Western and Eastern Siberia, spirits with wolf and dog features were the protagonists and masters of human destinies, while the fishermen and hunters of the Amur Valley had spirits in the guise of the taiga predator—a tiger.

Conclusions

Analysis of the shamanic sculpture of the Nanai people makes it possible to regard this as a phenomenon combining a number of semantic functions. For example, a set with the double meaning (of a dog and a tiger) indicates the cultural and mental fields, in which the figurines acquired their content. Shamanic sculptures were created as a means of communicating with the invisible world, in which the role of mediator was played by a shaman. This role determined the information content of a sculpted representation. In Nanai shamanism, wooden figures sewens performed a double function— as containers of spirits and neutralizers of their power. Representation semantics contains information about the category, character of the spirit, its position in the shamanic iconography, as well as personal participation of the shaman in its “processing”. It can be assumed that the configuration and design of each figure were used by the shaman as mnemonics, which helped him to orient himself in the spiritual realm. Accordingly, both individual images and their totality functioned as a sacred language. Conventionality in the transmission of images served as a basis for filling them with different ideological content.

The image of an animal with a horizontally elongated body and tail, embodied in wooden figurines, was spread over a vast territory. In different regions of Siberia and the Far East, it has his own semantic meaning: from wolfdog to tiger. In the Amur Valley, a paired image (one of streamlined form with a narrowed end, the other angular with a thickening at the end of the tail or with a forked tail) combines the meanings of a dog, and each separately, a tiger and tigress. There is a deeper connotation in its interpretation. The semantic duality associated with dog and tiger indicates the cultural layers of different times, with the Tungus, Paleoasiatic, and Manchu (Chinese) roots. The ideas of domestic animal and wild predator, embodied in the ritual sculpture of the Nanai people, should also be perceived as actualization of social life, which was refracted in the sacred realm. Dogs played an important role in the life of almost all peoples of Siberia and the Far East; but in the shamanic iconography of the Nanai people, its symbolic function served as a basis for developing the profile of other spirits. The imported image of a tiger was a secondary link, expressing the aspect of social demarcation.

It can be concluded that Nanai ritual sculpture has lost its religious and practical content along with the decline of shamanism in the Amur region; its images have begun to be interpreted only in a historical, cultural, and symbolic context.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the staff of the Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East IAET SB RAS, and to the residents of villages of the Solnechny, Nanaisky, and Ulchsky Districts, Khabarovsk Territory, for their help in studying the issue. Special thanks go to the staff of the museum for the opportunity to use and publish the materials from the ethnographic collection of the Nanai people.

Список литературы The tiger-dog and its semantics in the Nanai Shamanic sculpture: cultural and cognitive aspects

- Artemieva E.Y. 1999 Osnovy psikhologii subyektivnoi semantiki. Moscow: Nauka.

- Baldick J. 2012 Animal and Shaman. Ancient Religions of Central Asia. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Bereznitsky S.V. 2003 Klassifikatsiya kultovoi atributiki korennykh narodov Dalnego Vostoka Rossii. In Tipologiya kultury korennykh narodov Dalnego Vostoka Rossii (materialy k istoriko-etnograficheskomu atlasu). Vladivostok: Dalnauka, pp. 190–220.

- Bulgakova T.D. 2016 Kamlaniya nanaiskikh shamanov. Norderstedt: Verlag der Kulturstiftung Sibirien SEC Publications.

- Campbell J. 2002 Mifi cheskiy obraz. Moscow: Akt.

- Cherenkov S.E., Poyarkov A.D. 2003 Volk, shakal. Moscow: Astrel, AST.

- Flier A.Y. 2012 Proiskhozhdeniye kultury: Novaya kontseptsiya kulturogeneza. In Informatsionnyi gumanitarnyi portal “Znaniye. Ponimaniye. Umeniye”, No. 4 (July–August). URL: http://www.zpu-journal.ru/e-zpu/2012/4/Flier_The-Origin-of-Culture/ (Accessed February 21, 2020).

- Folklor yukagirov. 2005 Moscow, Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Geertz Cl. 1973 The Interpretation of Culture: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. Istoriya i kultura orochei: Istoriko-etnografi cheskiye ocherki. 2001 St. Petersburg: Nauka.

- Ivanov S.V. 1937 Medved v religioznom i dekorativnom iskusstve narodnostei Priamurya. In Pamyati V.G. Bogoraza (1865–1936). Moscow: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 1–44.

- Ivanov S.V. 1970 Skulptura narodov Severa Sibiri. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Kubanova T.A. 1992 Ritualnaya skulptura nanaitsev. Komsomolsk-on-Amur: [Tip. APO im. Gagarina].

- Lipsky A.N. 1925 Vvedeniye. In Pervyi tuzemnyi syezd DVO. Khabarovsk: pp. 5–52 (V–LII).

- Lopatin I.A. 1922 Goldy amurskiye, ussuriyskiye i sungariyskiye. Vladivostok.

- Losey R.J., Bazaliiskii V.I., Garvie-Lok S., Germonpré M., Leonard J.A., Allen A.L., Katzenberg M.A., Sablin M.V. 2011 Canids as persons: Early Neolithic dog and wolf burials, Cis-Baikal, Siberia. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, vol. 30 (2): 174–189.

- Losey R.J., Nomokonova T., Gusev A.V., Bachura O.P., Fedorova N.V., Kosintsev P.A., Sablin M.V. 2018 Dogs were domesticated in the Arctic: Culling practices and dog sledding at Ust’-Polui. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, vol. 51: 113–126.

- Maltseva O.V. 2008 Traditsionnye vozzreniya nanaitsev v kultovoi skulpture (po dnevnikovym materialam V.A. Timokhina, 1960–70-e gody). In Zapiski Grodekovskogo muzeya, iss. 20. Khabarovsk: Izd. Khabar. kraevogo kraeved. muzeya, pp. 164−169.

- Mamontova N. 2015 Language as mechanism of systemic foundation: Tungus-speaking groups in the Far East. Asian Ethnicity, vol. 17 (1): 48–66.

- Nanaiskiy folklor. Ningman, siokhor, telungu. 1996 N.B. Kile (comp.). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Nanaitsy. 2019 Katalog kollektsii iz sobraniya Khabarovskogo kraevogo muzeya im. N.I. Grodekova. G.T. Titoreva et al. (comp.). Krasnoyarsk: Yuniset.

- Onenko S.N. 1980 Nanaisko-russkiy slovar. Moscow: Rus. yaz.

- Ostrovsky A.B. 2009 Ritualnaya skulptura narodov Amura i Sakhalina. Putevodnaya nit chisel. St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya.

- Ostrovsky A.B. 2019 Antropologiya myshleniya: Izbrannye statyi 1990–2016 gg. St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya.

- Ostrovsky A.B., Sem T.Y. 2019 Kody kommunikatsii s bogami: (Mifologiya i ritualnaya plastika ainov). St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya.

- Perekhvalskaya E.V. 2008 Russkiye pidzhiny. St. Petersburg: Aleteiya. Priamurye. Fakty, tsifry, nablyudeniya. 1909 Moscow.

- Samar A.P. 2011 Traditsionnoye sobakovodstvo nanaitsev. Vladivostok: Dalnauka.

- Samar E.D. 2003 Pod senyu rodovogo dreva. Zapiski ob etnokulture i vozzreniyakh gerinskikh nanaitsev roda Samande-Mokha-Mongol/roda Samar. Khabarovsk: Kn. izd.

- Savelieva V.N., Taksami C.M. 1970 Nivkhsko-russkiy slovar. Moscow: Sov. entsikl.

- Schrenck L.I. 1883–1903 Ob inorodtsakh Amurskogo kraya. In 3 vol. St. Petersburg: Izd. AN.

- Sem T.Y. 2001 Sobaka-mergen v folklore i ritualakh nanaitsev. In Ritualnoye prostranstvo kultury: Materialy mezhdunar. foruma. St. Petersburg: pp. 101–104.

- Sem T.Y. 2002 Shamanizm tungusoyazychnykh narodov Sibiri i Dalnego Vostoka po materialam REM. In Rasy i narody, iss. 28. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 226–242.

- Shimkevich P.P. 1896 Materialy dlya izucheniya shamanstva u goldov. In Zapiski Priamurskogo otdeleniya IRGO, vol. II, iss. 1. Khabarovsk: [Tip. kantselyarii Priamur. general-gubernatora].

- Shirokogoroff S.M. 1919 Opyt issledovaniya shamanstva u tungusov. In Uchenye zap. ist.-fi lol. fak. v g. Vladivostoke, vol. 1. Vladivostok: [Tip. obl. zemsk. upravleniya], pp. 47–108.

- Shirokogoroff S.M. 1935 Psychomental Complex of the Tungus. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

- Smolyak A.V. 1976 Predstavleniya nanaitsev o mire. In Priroda i chelovek v religioznykh predstavleniyakh narodov Sibiri i Severa (vtoraya polovina XIX – nachalo XX v.). Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 129–160.

- Smolyak A.V. 1991 Shaman: Lichnost, funktsii, mirovozzreniye. Moscow: Nauka.

- Sokolova Z.P. 1998 Zhivotnye v religiyakh. St. Petersburg: Lan.

- Stepanoff C., Marchina C., Fossier C., Bureau N. 2017 Animal autonomy and intermittent coexistences. North Asian modes of herding. Current Anthropology, vol. 58 (1): 57–81.

- Sternberg L.Y. 1933 Gilyaki, orochi, goldy, negidaltsy, ainy. Khabarovsk: Dalgiz.

- Titoreva G.T. 2012 Seveny: Katalog kultovoi skulptury iz sobraniya KhKM im. N.I. Grodekova. Khabarovsk: Khabarov. kraevoi muzei im. N.I. Grodekova.

- Zelenin D.K. 1936 Kult ongonov v Sibiri. Perezhitki totemizma v ideologii narodov Sibiri. Moscow, Leningrad: AN SSSR.