The triquetras from the Filippovka kurgans, Southern Urals

Автор: Fedorov V.K.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145467

IDR: 145145467 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.1.101-109

Текст обзорной статьи The triquetras from the Filippovka kurgans, Southern Urals

The sign of triquetra*, known in many cultural traditions of antiquity, occurs relatively infrequently at sites from the Scythian period in the Great Steppe. Specialists most often consider it together with swastikas and “swirl rosettes” (Korolkova, 2009; Beisenov et al., 2017; Dzhumabekova, Bazarbaeva, 2018), mostly regarding them as solar symbols. Archaeological evidence contains both images of triquetras and zoomorphic objects in which the heads or bodies of various animals bear a resemblance to this sign. In the southern Urals, the triquetra is known only from evidence discovered in royal kurgans 1 and 4 at the Filippovka I cemetery (Fig. 1), which includes 31 triquetra images, all made of gold, or appearing on gold items. There were no swastikas at Filippovka I, and “swirl rosettes” were used for decorating only very few elements of a horse harness (Yablonsky, 2013: Cat. 45, 48, 49, 2741). Triquetras appear on gold onlays of wooden vessels, on sewn plaques, and in gold inlays on a sword. Triquetras and “swirl rosettes” in Filippovka I do not show any “points of contact”, which makes it possible to focus solely on the triquetra ornament.

55*

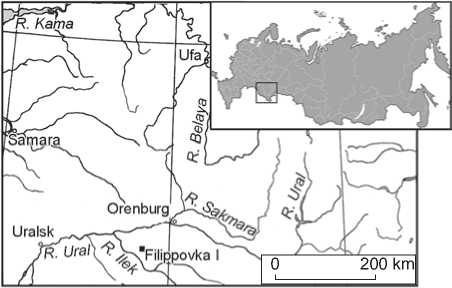

Fig. 1 . Location of the Filippovka I kurgan cemetery.

Objects of study and discussion of the results

The evidence from Filippovka I, dated to the interval from the turn of the 5th–4th to the third quarter of the 4th century BC (Treister, Yablonsky, 2012: 284), include the following items with the image of triquetra:

-

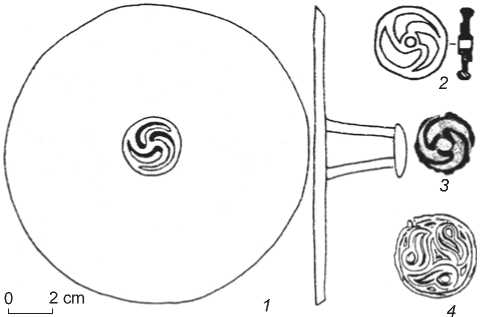

1) Five small flat onlays on wooden vessels in the form of triquetra, kurgan 1, cache 1 (Kollektsii…, 2018: Cat. 540, 582–585) (Fig. 2);

-

2) An open-work onlay on a vessel, the lower part of which shows the image of triquetra with strongly curved crescent branches, inscribed in a circle and emphasized by holes in the form of “comma”-magatama*, kurgan 1, cache 1 (Ibid.: Cat. 335) (Fig. 3);

-

3) The hollow handle of a vessel in the form of horse figurine showing the recessed image of a triquetra with the spirally twisted ends of branches on each thigh, kurgan 1, cache 1 (Ibid.: Cat. 466) (Fig. 4, 1 );

-

4) 20 argali figurines with similar images of triquetra, kurgan 1, cache 2 (Ibid.: Cat. 785–804) (Fig. 4, 2 );

-

5) An iron sword showing three images of triquetra with the spirally twisted ends of branches on its gold-inlaid blade, kurgan 4, burial 2 (Yablonsky, 2013: Cat. 296) (Fig. 5).

Five onlays from kurgan 1 represent the triquetra, but lack any context. They are small in size, ranging from 1.1 × 1.3 cm to 1.6 × 2.0 cm. On four onlays, slightly curved branches of a triquetra pattern are bent to the right, and on one onlay to the left (see Fig. 2). In fact, they do not stand out from other small onlays abundantly found in this kurgan, which mostly have the form of various curls (Fedorov, 2012: Fig. 13, 5; 14, 5). A similar situation has been observed in the antiquities of the Middle Sarmatian period in the Kuban region, where gold sewn plaques in the form of triquetra were only one of many types of plaques (Gushchina, Zasetskaya, 1994: Pl. 54, 6; Marchenko, 1996: Fig. 11, 72), but because of a large chronological gap between them and the Filippovka onlays, this should be assumed to be a mere coincidence.

The rest of the Filippovka triquetras are explicitly associated with other images, which provides a rationale for identifying their meaning. The onlay with a triquetra inscribed in a circle is flat; its size is 3.8 × 2.5 cm (see Fig. 3). The symbol was engraved; it has a small circle in the middle; the spaces between the branches constitute the holes in the form of “comma”-magatama. The circle with the inscribed triquetra constitutes a single whole with trapezoidal plate, which shows a griffin head with a strongly elongated closed beak without its cere, and two curls behind the back of the head. Several similar images are known from Filippovka I; for example, the image at the end of the handle of a wooden vessel (Kollektsii…, 2018: Cat. 453).

Similar triquetras have been associated with other cultures of nomads inhabiting the eastern part of the Eurasian steppes in the Early Iron Age. A small wheel, the shape of which is similar to the Filippovka design, was found in Northwestern China (Xinjiang), at the Yanbulake cemetery of the 7th–6th centuries BC (Shulga, 2010: Fig. 52, 25 ; 81, 32 ) (Fig. 6, 2 ). Such a triquetra is depicted on a bridle plaque from kurgan 3 of the Tasmola-5 cemetery of the same period (Kadyrbaev, 1966: Fig. 72) (Fig. 6, 3 ). Many other metal items show this type of design: it appears on the buttons of Tagar mirrors (Fig. 6, 1 ) and plaques (Chlenova, 1967: 85, pl. 21, 1 ; Kungurova, Oborin, 2013: Fig. 3, 1 ; 9, 1 ), but never combined with the image of a bird of prey. Triquetras associated with this image have been found in different regions and in different periods. The best known objects have triquetras ending in all branches in the form of the heads of a bird of prey. Such images have nothing to do with the Filippovka representations. Perhaps only the gold “badge” from kurgan 2 at the Duzherlig Khovuzu I cemetery of the Sagly culture of the 6th–5th centuries BC shows some similarities. The triquetra on that badge is composed of three images representing the head of a bird of prey inscribed in a circle; moreover, these heads resemble “comma”-magatamas in their shape (Grach, 1980: 35–36, fig. 68) (Fig. 6, 4 ).

Parallels to the Filippovka triquetra, which are contextually associated with the image of a bird of prey, have been found in the materials of the Pazyryk culture, on the felt decorations of a saddle cover from the Second Bashadar kurgan. The full-face volume of the chest with two griffin representations was rendered by three “comma”-magatamas made of felt of a different color, forming triquetra (Rudenko, 1960: Pl. CXVII, 2 ). The direction of the branches is clockwise in one figure, and

Fig. 2 . Gold onlays on wooden vessels in the form of triquetras, Filippovka I, kurgan 1, cache 1 (after (Kollektsii…, 2018: Cat. 540, 582–585)).

Fig. 3 . Gold onlay on a wooden vessel with the representation of the triquetra inscribed in a circle (after (Kollektsii…, 2018: Cat. 335)).

counterclockwise in the other figure (Fig. 7). A circle with a triquetra combined with the image of griffin head is very similar to the Filippovka representation.

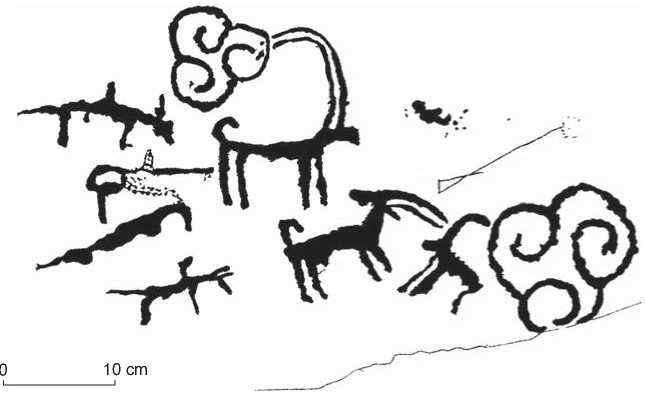

If the origin of the design with branches formed by the figures in the form of the “comma”-magatama can be easily established (from the steppes east of the southern Urals), the origins of the image of a triquetra with narrow spirally twisted branches, which is the most common in Filippovka I, are not clear. Such signs have sometimes been found on petroglyphs; for example, on stone 40 at the foot of Mount Aldy-Mozaga in the Upper Yenisei

Fig. 4 . Gold animal figures with recessed representations of triquetras on the thighs, Filippovka I, kurgan 1.

1 – vessel handle in the form of horse figurine, cache 1 (after (Kollektsii…, 2018: Cat. 466)); 2 – argali figurine, cache 2 (after (Kollektsii…, 2018: Cat. 801)).

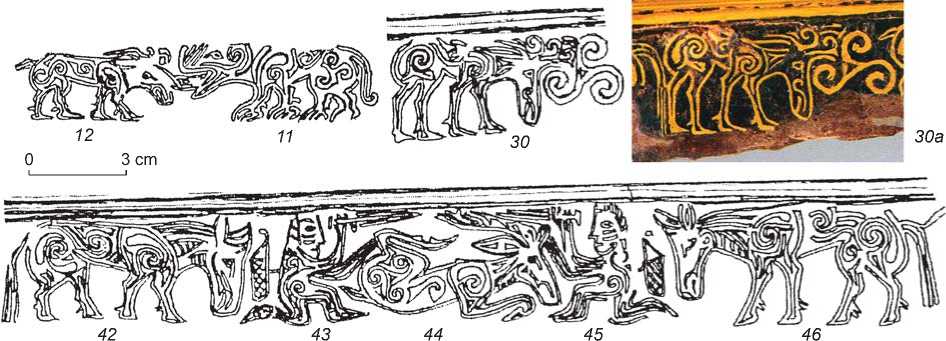

Fig. 5 . Representations on the gold-inlaid blade of an iron sword (their numbers in linear compositions are indicated), Filippovka I, kurgan 4, burial 2.

11 , 12 , 30 , 42 – 46 – after (Yablonsky, Rukavishnikova, Shemakhanskaya, 2011: Fig. 5, 7, 8); 30a – after (Yablonsky, 2013: 87, cat. 296).

Fig. 6 . The sign of the triquetra on items from Northern Kazakhstan and Eastern Siberia.

1 – bronze mirror, the village of Tesinskoye, Minusinsk Basin, Tagar culture (after (Chlenova, 1967: Pl. 21, 1 )); 2 – bronze wheel, the Yanbulake cemetery, Xinjiang (after (Shulga, 2010: Fig. 52, 25 )); 3 – iron bridle plaque with gold inlay, Tasmola-5, Northern Kazakhstan, Tasmola culture (after (Kadyrbaev, 1966: Fig. 72));

4 – gold “badge”, Duzherlig Khovuzu I, Tuva, Saglyn culture (after (Grach, 1980: Fig. 68)).

Fig. 7 . Fragment of a saddle cover, the Second Bashadar kurgan, Pazyryk culture (after (Rudenko, 1960: Pl. CXVII, 2)).

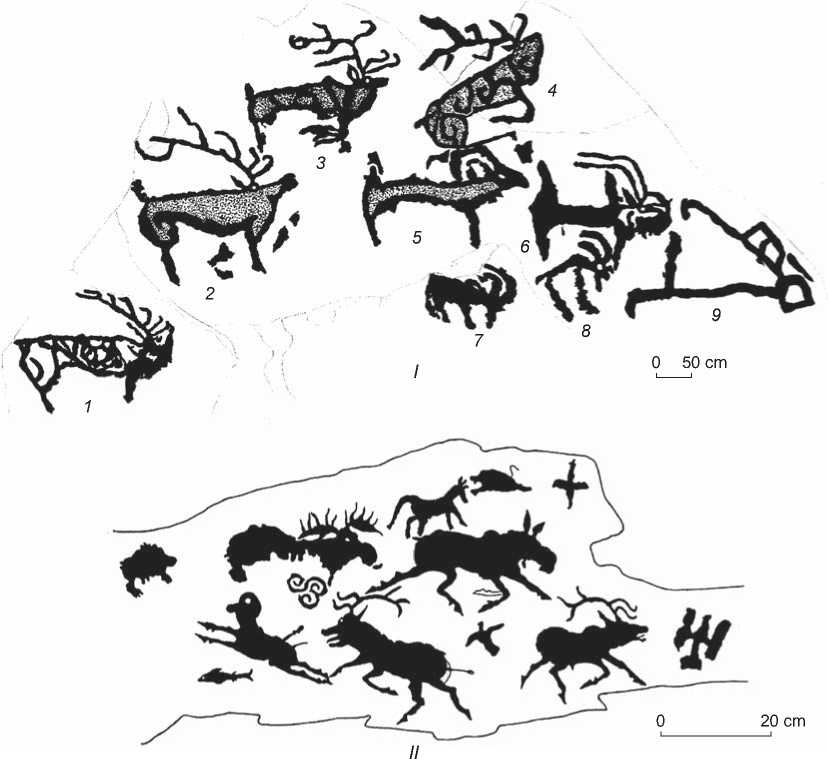

River region (Devlet E.G., Devlet M.A., 2005: Fig. 197) (Fig. 8, II ), but their dating is difficult: they can be both earlier and later than the Filippovka representations. Images of a triquetra recessed into metal, that is, representations similar to the animal figures from Filippovka I, are well known from the Koban culture of the Northern Caucasus, appearing on the shields of semioval (segment-like) buckles (Kozenkova, 2013: Pl. 35, 5 , 7 ). Despite the great resemblance to the Filippovka representations, they cannot be genetically linked. The Koban buckles date from the 13th to the first half of the 12th century BC (Ibid.: 75) and have only intra-Caucasian parallels (Ibid.: Pl. 35, 10 , 12 ).

The sole parallel to three triquetras made of gold on the iron blade of the sword in terms of manufacturing method appears on a bridle plaque from Tasmola-5, yet the sign is of a different type (see Fig. 6, 3 ). In a special article on this sword, the authors examined all the human and animal representations in detail. The number, to which we will further refer to, was assigned to each representation. The authors suggest that the compositions revealed on the planes of the blade depict “the legend of the warrior-hero and warrior-sorcerer” (Yablonsky, Rukavishnikova, Shemakhanskaya, 2011: 240). Yet, very little attention in the article was paid to triquetras, whereas from our point of view they played the key role in the narrative. One triquetra twisted clockwise is depicted on the thigh of the predator with clawed legs (see Fig. 5, 11 ), which opens its mouth and is trying to grab the deer’s muzzle (see Fig. 5, 12 ), but, according to the authors of the article, instead, the predator’s mouth is threatened by the antlers directed forward. If this is true, what we have here is the extremely rare case of a successful confrontation of a herbivore against a predator. In all other “torment scenes”, ten more of which appear on the blade, the predator grabs the prey by its muzzle, which is generally typical of the Filippovka art (only in one composition, the second predator is grabbing the deer by its back). In the image under consideration, the deer’s muzzle is indeed directed downward past the mouth of the predator; the bent “neck-muzzle” forms a rather steep arc, as is usually represented in the animals that are not under attack (see Fig. 5, 30 , 30a ). In the deer under attack, this bend is very small ( 9 , 17 , 20 , 31 , 39 , 41 ) or this line is almost straight ( 22 , 24 ). The antlers in many figures are poorly preserved. Wherever they are clearly distinguishable, the antlers are bent far back and partially stick straight up; otherwise, they would have interfered with the scene of the torment. The antlers are poorly preserved in the composition under consideration. One antler bent back is visible; one prong sticks up; another short prong is directed forward and down. As far as the forward direction of the prongs, resulting in placement of “antlers in the mouth of the predator” (Ibid.: 233), is concerned, this observation is not obvious, since the incrustation lines seem to be displaced, most likely owing to the poor preservation of the blade in this area. The completely disintegrated representation 35 is located on the corresponding section on the backside of the blade. Thus, “the composition of a deer repelling a predator’s attack” (Ibid.) is probably the result of reconstruction flaws, and this is the usual “torment scene”. This being said, more complex “relations” between the deer and predator cannot be completely excluded. This is the only scene where a triquetra is depicted on the body of the predator, and maybe it was not done by chance. On the back of the sword, a triquetra then appears on the figure of the deer, and moreover it is twisted in the opposite direction.

Fig. 8 . Rock images with representations of triquetras on animal figures.

I – design on the shoulder of deer leader ( 4 ), petroglyphs of Mount Kherbis, group 5 (after (Kilunovskaya, 2003: Fig. 7, 4 ));

II – a triquetra projected onto the body of male elk, petroglyphs at the foot of Mount Alda-Mozaga, stone 40 (after (Devlet E.G., Devlet M.A., 2005: Fig. 197)).

The image of a triquetra with branches twisted clockwise appears on the free field of the blade of the same sword, between the figures of a deer and a mountain ram, and it touches the deer antlers (see Fig. 5, 30). The authors of the article even suggest that this sign “is a continuation of the antlers on the inclined deer head” (Ibid.: 235). This seems not to be the case, since the sign is depicted separately, but very close to the antlers. Triquetras located among the figures of animals (mainly herbivores) are a fairly well-known motif among the petroglyphs of the Altai-Sayan region. Sometimes they are isolated from other figures, like for example at Kuilug-Khem (stone VIII) (Devlet, 2001: Pl. 6), but sometimes they directly interact with the figures. In Kuilug-Khem VII, seven triquetras were placed on the stone among the human and animal representations; the two largest triquetras touch the horns of mountain goats (Ibid.: Pl. 4, 3; 5) (Fig. 9). The motif of touching the triquetra with horns, which is also present on the Filippovka sword, emphasizes that this ornament and the herbivores are attracted to each other. In some figures, a triquetra was depicted on the figure of the animal. For example, in the group of five petroglyphs on Mount Kherbis (Tuva), a triquetra was depicted on the shoulder of one out of four deer, which is located in the highest position, is going forward and upward, and seems to be the obvious leader (Kilunovskaya, 2003: Fig. 7, 4) (see Fig. 8, I, 4). On stone 40 at the foot of Mount Aldy-Mozaga, in the Upper Yenisei region, an expressive triquetra with the spirally twisted branches was projected onto the figure of male elk approximately in the shoulder area (Devlet E.G., Devlet M.A., 2005: Fig. 197) (see Fig. 8, II).

As has been already mentioned, in the evidence from Filippovka I, the image of the triquetra was most frequently found on the figures of herbivores. The fact that this is not simply an ornamental decoration is confirmed by both the design and its location on the thigh of the central character in the composition of a

Fig. 9 . Representations of mountain goats touching triquetras with their horns, Kuylug-Khem petroglyphs, stone VII (after (Devlet, 2001: Pl. 4, 3 )).

deer sacrifice appearing on the blade of the sword. A clue to the semantics of the sign among the early nomads of the southern Urals can probably be found in this scene. It is hardly possible to doubt that the deer opposing the predator with a triquetra on its thigh in the compositions on the blade, the deer touching the triquetra with its antler, and the deer with triquetra on its thigh, are one and the same animal. The interpretations of the images on the sword that have been proposed so far have been based on the assumption that the main characters in this “story” are human. The “story of the deer with the triquetra” remains virtually beyond the scope of interpretation.

The scene of a deer sacrifice (see Fig. 5, 42–46) has attracted the greatest attention among all the compositions on the blade of the sword. Two people are grabbing a lying deer, one holding the deer by the leg turned upside down, another by the antlers or ear, and each person is directing forward the other hand with a dagger. The persons who grabbed the deer look alike in every way: they have the same postures, figures, faces, and weapons (daggers and quivers with bows hanging behind their backs). The horses behind each person are also exactly alike. V.G. Kotov and R.B. Ismagil, who suggests that the composition represents the confrontation of two brothers, because the characters point their weapons not so much at the deer but at each other (2013: 80), must have been right in their interpretation. The subject of confrontation between brothers is very typical of many mythologies in the world, including Iranian mythology, where the motif of the righteous protagonist dying from the hand of his evil and envious brother is not uncommon. Yima and Iraj die in this way. Moreover, these events had global consequences: after assassination of Yima, evil triumphed on earth, and the death of Iraj determined the fate of Turan to be the eternal enemy of Iran. In the upheavals of this enmity, the leaders of the Iranians and Turanians sought to seize *Hvarnah, lost by their common ancestor Yima, and fratricides were committed again: Frangrasyan killed his brother Agreras, and Rustam died at the hand of his brother Shaghad*.

The composition of deer sacrifice could have represented the allegory of the struggle between the Aryans and Turanians for *Hvarnah, which was depicted in the form of deer with triquetra on its thigh. Each of the characters is pulling the deer in his direction, and at the same time seeks to hit the other character with a dagger. Chasing and capturing *Hvarnah in the form of a wild, predominantly ungulate, animal is one of the frequent motifs in the Iranian art. For example, Iranian shahs striking various animals (rams, mountain goats, gazelles, wild boars, or lions) were often depicted on Sasanian dishes, and this is the motif of capturing *Hvarnah (Trever, Lukonin, 1987: 56–57). The prey also include deer; moreover, in one composition (a dish from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art), Shah Yazdegerd I hits a deer with a figure on its thigh, consisting of three semicircles, that is, the figure similar to triquetra (Plate…, 399–420) (Fig. 10). We should note that real triquetra on the bodies of herbivores in hunting scenes (for example, on the thigh and shoulder of a gazelle grabbed by an eagle) are also known from Sasanian dishes (Trever, Lukonin, 1987: 115) (Fig. 11).

Therefore, the sword from burial 2 of kurgan 4 presents a kind of “story of *Hvarnah”. Lost by Yima, it abides in nature, being sometimes in the sky and sometimes in the depths of the sea. On the blade of the

Fig. 10 . Sasanian dish with a representation of Shah Yazdegerd I striking a deer with a three-partite figure on its thigh, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (after (Plate…, 399–420).

Fig. 11 . Sasanian dish with a representation of an eagle grabbing a gazelle. The signs of triquetra are shown on the shoulder and thigh of the gazelle. The State Hermitage Museum (after (Trever, Lukonin, 1987: 115)).

sword, the events happening to *Hvarnah are probably shown in the form of its transition from animal to animal—from the world of darkness (wolf) to the world of light (deer). At the time when *Hvarnah was abiding in the “sun deer”, a struggle ensued between the brothers—the Aryan and the Tur. The result of the struggle is not shown on the sword, but contextually it is expressed in the idea that *Hvarnah becomes in the possession of the person holding this sword.

The remaining images of triquetra in the materials of Filippovka I can also be interpreted as a part of the plot related to *Hvarnah. It flew away from Yima in the form of the bird Varagn (eagle, falcon), and in the same guise returned to Traitaunas. The triquetra with the head of a bird of prey on top obviously represents *Hvarnah in this form. In the legend of Ardashir, *Hvarnah accompanied him in the form of a beautiful ram, and then appeared on the croup of Ardashir’s horse. This corresponds to the images of triquetra on the figures of rams and horse.

Conclusion

A search for parallels to the Filippovka triquetras has revealed that the main distribution area of the design inscribed in a circle and formed by means of recesses/ holes in the form of “commas” in the 7th–4th centuries BC was the steppe belt east of the southern Urals. Rock drawings depicting triquetras, which touch the antlers and are placed on the bodies of herbivores (the features observed in Filippovka I), also appear in the same region.

The origin of the triquetra with the spirally twisted ends, which have been most often found among the materials of the site, is not very clear. Signs with similar morphology are known from the complexes of very early burial grounds of the Koban culture, located far to the west. In the early and classic Scythian culture, and in the antiquities of the Sauromatians inhabiting the Don region and the Volga region, this design seems not to appear at all. Moreover, the triquetra appears nowhere else in the southern Urals, except for Filippovka I. To the east of the Urals, similar triquetras are known only on petroglyphs, the exact dating of which is difficult. Nevertheless, an eastern origin for this type of ornament is more likely than a western origin.

In Filippovka I, the images of triquetra numbering over 30 specimens have been found only among the evidence from “royal” kurgans 1 and 4. These circumstances, as well as the fact that all of them were either made of gold or appeared on gold items, indicate that the design belongs to the symbols only the highest nobility of the early nomads inhabiting the southern Urals could use. The context of the images suggests that the sign of triquetra is a symbol of *Hvarnah. The chief or military leader, who was in possession of *Hvarnah, fell under the special protection of gods and as a result became invincible, invulnerable, and successful. Such an idea could be very popular in the militarized society of the early nomads who inhabited the southern Urals and were oriented in their external relations toward the Achaemenid Iran. The triquetra whose image reached the southern Urals from the eastern regions of the Great Steppe belt, could have been reinterpreted as a symbol of *Hvarnah in the process of contacts with Iran. However, it cannot be ruled out that such notions existed in the nomadic milieux, not only in the southern Urals, but also in the areas located to the east. After studying the semantics of the headdress from Aluchaideng, the Chinese scholar Zhen Ziming came to the conclusion that, “at that time, the tribes in Ordos believed in Zoroastrianism. On this basis, we may speak about various cultural exchanges and ethnic interactions between the nomads of Eurasia along the Silk Road” (Zhen Ziming, 2015: 380). Any assumption that based on the presence of Zoroastrianism in Ordos is certainly too bold, but the fact that the Ordos nomads could have professed some form of pre-Zoroastrian religion, similar to the beliefs of the nomads in the southern Urals, cannot be ruled out. The presence of zoomorphic triquetra among the finds in Aluchaideng (Kovalev, 1999: Fig. 2, 11 ) should also be mentioned in the context of our discussion.

Acknowledgment

Ethnography: Collection Resources, Research, and New Information Technologies”.