Theoretical approaches to studying people's motivation for creative labor activity in the socio-humanitarian thought

Автор: Shabunova Aleksandra A., Leonidova Galina V., Ustinova Kseniya A.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Theoretical issues

Статья в выпуске: 4 (58) т.11, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article raises the issues of motivation in the context of individual approaches (Freudian, behavioral, cognitive-psychological, etc.) in the framework of theoretical-personal and theoretical-associative fields. The goals of the article are as follows: to structure the main existing approaches to the study of motivation, and to determine the provisions that can be used in the framework of the motivation for people’s creative labor activity. The study used general logical methods and techniques, such as system approach, generalization, analysis, and synthesis. We conclude that the main source of people’s activity is need-based tension, and the aim is to eliminate it using external incentive factors. We show that the nature of behavior will be determined by the degree of consistency between different groups of motives, correlation of motives and external goals, and in the absence of such coordination - by volitional mechanisms of regulation. We point out that scientific literature contains no unambiguous definition of motivational-stimulating mechanism; the paper provides its interpretation from the standpoint of behavioral approach and A.N...

Motivational-stimulating mechanism, motive, stimulus, creative activity, labor activity

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147224086

IDR: 147224086 | УДК: 331.1 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2018.4.58.6

Текст научной статьи Theoretical approaches to studying people's motivation for creative labor activity in the socio-humanitarian thought

Regardless of the stage of socio-economic development of territories and individual organizations, personnel motivation remains a relevant issue. Low creative activity of employees and the absence of new forms and methods of motivation for creative work are considered as the most critical barriers to economic development and innovation [Tether et al. A literature review on skills and innovation ... 2005]. Employers run the risk of losing valuable personnel and having problems attracting talented employees, if they do not pay attention to motivation [Dessler G. Human resource management . 2003].

The socio-economic reforms of the 1990s had a significant impact on the system of personnel motivation in Russian enterprises and organizations. The transition to a market economy was accompanied by their gaining economic independence; thus, the level of ideological self-consciousness of an individual was no longer recognized as a major driver of labor motivation; it was replaced by the achievement of a certain level of productivity by work teams and individual employees and by the amount of financial incentives. At present, in connection with the transition toward innovative development, non-financial incentives for workers become relevant again [Raznodezhina E.N., Krasnikov I.V. Motivation of the market organization of work in modern conditions. 2011].

Creating a mechanism to promote work motivation and improve employees’ performance, as well as studying the factors that influence such motivation [Skripnichenko L.S. The study of work motivation specifics ... 2015] are coming to the fore in social science.

The problems of personnel motivation are raised in both domestic and foreign scientific literature. There are many schools and directions on this issue. Russian researchers in this field include A.P. Volgin, V.P. Galenko, M.V. Grachev, E.E. Starobinskii, and V.V. Travin; foreign – A. Maslow, F. Herzberg, D. McClelland and others. Foreign researchers [e.g., Hugo M. Kehr. Integrating implement motives, explicit motives, and perceived abilities ... 2004] analyze inter-group differences that affect the complexity (simplicity) of achieving the goals in terms of similar qualifications, as well as mechanisms for achieving goals and their modification.

However, it should be emphasized that existing theories do not give sufficient attention to implicit motives and to the mechanisms of overcoming the conflict between implicit and explicit motives [Brunstein J.C., Schul-theiss O.C., Grassmann R. Personal goals and emotional well-being ... 1998; Emmons R.A., McAdams D.P. Personal strivings and motive dispositions ... 1991; McClelland D.C., Koestner R., Weinberger J. How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ . 1989; Spangler W.D. Validity of questionnaire and TAT measures of need for achievement ... 1992]. At the same time, there is no systematization of traditional concepts of motivation, and the attention paid to non-financial incentives for employees is insufficient. In view of the above, the purpose of our article is to analyze the existing theoretical approaches to the study of motivation in foreign scientific thought.

-

I. Overview of the main theoretical approaches to the study of motivation

Attempts to study the behavior were made long ago, with an emphasis on promoting and implementing targeted actions to manage them. Over time, more and more attention in the explanation of not only behavior, but also perception and thinking, was given to motivation. Foreign sources mentioned its features such as “inner strength”, “stimulus to action” [Russell Ivan L. Motivation. 1971]. For example, motivation can be interpreted from the standpoint of an “internal force” that causes the need to satisfy basic needs [Yorks Lyle. A radical approach to job enrichment. 1976], as well as productivity enhancing factor that helps act purposefully or improve the ability to act [Kast Fremont E., Rosenzweig James E. Organization and management... 1970].

Along with motivation, scientific literature contains a number of related concepts, similar in form, but different in content, which include “labor motivation” and “motivation for labor activity”. The former is often considered from the standpoint of the intrapersonal process of forming motives for work, the latter – in terms of those actions that are taken, for example, by organizations and encourage the employee to work.

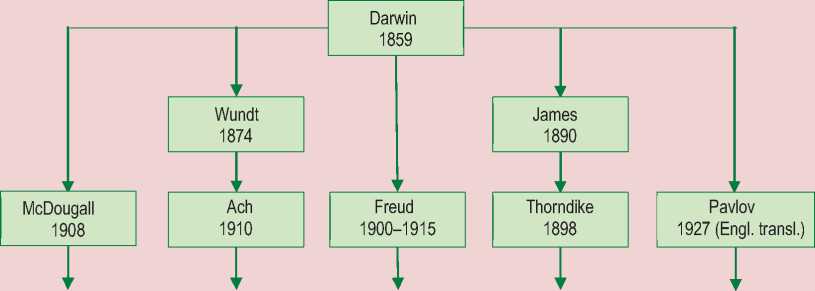

Returning to the original concept of motivation, we note that among the areas of research are the following: 1) theoretical and instinctive (Lorenz, 1937, 1943; Tinbergen, 1951, etc.); 2) theoretical and personal (Levin, 1926, 1935; stern, 1935; Maslow, 1954; McClelland, 1953, 1961; Festinger, 1957, 1964; Atkinson, 1957, 1966, 1970, etc.) and 3) theoretical and associative (Woodworth, 1918; Tolman, 1932, 1952; Young, 1936, 1961; Duffy, 1932, 1962; Skinner, 1938, 1953; Hull, 1943, 1952, etc.) (Figure) .

The first direction explains human behavior on the basis of instincts and motives, the second one emphasizes the allocation and description of personal properties, the third one considers the adaptation to changing conditions and analyzes how the organism responds to stimulation.

Original directions of motivation research

Theory of instinct Theoretical and personality direction Theoretical and assotiative direction

Psychology of activation

Psychology of learning

We do not attempt to cover all the existing approaches to the study of motivation and focus only on some of them in the framework of the theoretical and personal direction and the theoretical and associative direction (Freudian, behavioral, cognitive-psychological, etc.).

Freudian approach

NarziB Ach (1871—1946) and Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) were pioneers in this direction. The prerequisites of Freud’s theory were set out in 1895 in the Project for a Scientific Psychology, and in the final form – in 1915. The key role was given to internal “stimuli” rather than external ones, and an individual was considered as a complex energy system in which energy is provided by the neurophysiological state of excitation and is spent mainly on mental activity. It was argued that any activity (thinking, perception, memory and imagination) is determined by instincts that can have both direct and indirect influence on it. In a generalized form, Freud distinguishes two groups of instincts: life and death, considered from the standpoint of the source, purpose, object and stimulus. The need-based condition of the body (for example, hunger and thirst) is a source of instinct and the elimination or reduction of excitation is a goal. Any behavioral process within the framework of psychoanalytic theory is characterized from the standpoint of the orientation of energy toward an object (cathexis) and the obstacles to the satisfaction of an instinct (anticathexis).

Behavioral approach

The behavioral approach to the study of motivation emerged in the early 20th century (B. Skinner, K. Spence, E. Tolman, J. Watson, C. Hull, etc.). In its framework, the need emerging due to the deviation of physiological parameters from the optimal level was also recognized as the basis of activity. Motivation mechanism was reduced to a decrease or removal of the arising tension, and in case when its removal was impossible – to the use of reinforcement (external factors, incentives) [Major psychological theories of motivation...]. Among the latter, not only positive (awards, incentives), but also negative (punishment) aspects were considered. And the behavior itself was characterized by both positive consequences, which led to its consolidation, and negative consequences leading to its cessation. The prevalence of a particular type of behavior was thought to imply confidence in the existence of a direct link between activity and its effects. If there are no significant consequences for the individual, then there will be no intentions to behave in a particular way.

The relationship between motivation and subsequent behavior is considered either as direct or as mediated by cognitive processes (Tab. 1) .

Taking into account the above, we can mention the following theories: stimulusresponse theories such as learning theories of Watson (J. Watson, 1924), Guthrie (E. Guthrie, 1935) and Skinner (B.F. Skinner, 1938; 1953); on the other hand, there are theoretical approaches in which between stimulus and response there are cognitive processes: assessment of the actual situation, assessment of the consequences of events; self-assessment of the achieved results (F. Halisch, 1976; H. Heckhausen, 1978). Among such approaches, there are, for example, non-behavioral theories of Hull, Spence, Miller (C. Hull, 1952; K. Spence, 1956; N. Miller, 1959), which contain no statements concerning a close stimulusresponse relationship; variables such as needs and motivational characteristics are introduced between stimulus and response. Motivation is considered as an internal component that encourages an individual to work (the desire to do something better and/or faster) and is characterized from the standpoint of the importance and achievability of this result for the subject, including through his/her faith in his/her abilities [Modern psychology of motivation. 2002]. Another group of “intermediate” theories is represented by the theories of “expected value”, which takes into account the subjective probability of achieving (not achieving) the goals. Among them, in particular, Atkinson’s model of decisionmaking in risk conditions (J. W. Atkinson, 1957; 1964).

In the scientific literature, there is a variety of theoretical approaches to the study of motivation, in which attention is focused on the differences between explicit and implicit motives [Weinberger J., McClelland D.C. Cognitive versus traditional motivational models ... 1990; Koestner R., Weinberger J., McClelland D.C. Task-intrinsic and social-extrinsic sources of arousal for motives ... 1991]. Explicit motives serve as guidelines for tracking their actions [McClelland D.C. Scientific psychology as a social enterprise ... 1995], they are associated with the sphere of the conscious, with cognitive processes, for example, decisionmaking [McClelland D.C. How motives, skills, and values determine what people do . 1985; Spangler W.D. Validity of questionnaire and TAT measures of need for achievement ... 1992], and they are influenced to a greater extent by the social environment [McClelland D.C. How motivations, skills, and values determine what people do . 1985; Koestner R., Weinberger J.,

Table 1. Four groups of theories according to B. Weiner (1972)

|

Classification |

Structure |

Essence |

|

Mechanistic |

S-R |

Behavior is explained by the stimulus-response relationship (S-R). When behavior is analyzed, intermediate hypothetical constructs are not used. Representatives: Watson, Skinner and other associationists and behaviorists. |

|

S-construct-R |

Behavior is explained by the stimulus-response relationship (S-R). When behavior is analyzed, hypothetical mediating constructs – the need and the motive – are introduced. Representatives: Hull, Spence, Miller, Brown and other neo-behaviorists. |

|

|

Cognitive |

S-cognitive processes-R |

The action of thought processes is supposed between the incoming information and the final behavioral response. Behavior is mainly influenced by “waiting”. Representatives: Tolman, Lewin, Rotter, Atkinson, etc. |

|

S-cognitive processes-R |

Between the incoming information and the final behavioral response there is the action of mental processes, but the behavior is due to many cognitive structures and processes, such as information retrieval and personal constructs. Representatives: Heider, Festinger, Kelley, Lazarus, etc. |

McClelland D.C. Task-intrinsic and social-extrinsic sources of arousal for motives ... 1991]. Implicit motives, on the contrary, are associated with the unconscious [Maslow A. H. A theory of human motivation . 1943], with hidden behavioral aspects [McClelland D.C. et al. The achievement motive . 1953], the foundations of which are laid in one’s youth and which are relatively independent of social requirements [Koestner R. et al. Task-intrinsic and social-extrinsic sources of arousal for motives ... 1991; McClelland D.C. How motives, skills, and values determine what people do . 1985]. Examples include the motives for power and achievement [McClelland D.C. Scientific psychology as a social enterprise . 1995], the motives for “hope for success” and “avoiding failure” (fear) [Atkinson J.W. An introduction to motivation . 1964; Higgins E.T. Promotion and prevention ... 1998; Kanfer R., Heggestad E.D. Motivational traits and skills ... 1997].

Explicit and implicit motives are related to different aspects of personality [McClelland D.C. et al. How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ. 1989; Spangler W.D. Validity of questionnaire and TAT measures of need for achievement... 1992], so in some cases they are considered as independent variables [Brunstein J.C. et al. Personal goals and emotional wellbeing... 1998; McClelland D.C. How do selfattributed and implicit motives differ... 1989; Epstein S. Personal control from the perspective... 1998; Metcalfe, J., Mischel W. A hot / coolsystem analysis of delay of gratification...1999], which is confirmed in the study of Spangler [Spangler W.D. Validity of questionnaire and TAT measures of need for achievement... 1992]. A similar approach is contained in the goalsetting theory, which does not distinguish between these groups of motives and ignores the possibility of “strong-willed resolution” of the conflict between them. However, in some works [Cantor N., Blanton H. Effortful pursuit of personal goals in daily life ... 1996; Emmons R.A., McAdams D.P. Personal streams and motive dispositions... 1991; King L.A. Wishes, motives, goals, and personal memories... 1995; Sokolowski K. et al. When assessing achievement, affiliation, and power motives all at once... 2000], a conclusion is made about their interrelation and interdependence, and it is pointed out that they are considered from the positions of integrated structures [McClelland D.C. How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ. 1989; Sheldon K.M., Kasser T. Coherence and congruence... 1995].

The presence of some inconsistency between these groups of motives leads to the fact that the behavioral aspects they cause may also be in varying degrees of consistency [Brunstein J.C. et al. Personal goals and emotional well-being ... 1998; McClelland D.C. et al. How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ ... 1989]. In this case, a large mismatch between explicit and implicit motives may be accompanied by considerable differences in behavior. This can be manifested in intrapersonal conflict, in reduced labor productivity and well-being and even in health problems [Bazerman M.H. et al. Negotiating with yourself and losing ... 1998; McClelland D.C. How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ . 1989; Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation ... 2000; Sheldon K.M., Kasser T. Coherence and congruence ... 1995].

Heckhausen’s cognitive-psychological approach to the study of motivation [Heckhausen H. Hoffnung und Furcht in der Leistungsmotivation. 1963] takes into account such motivational aspects as hope of success (HS) and fear of failure (FF). It is noted that some people are motivated to solve problems by the satisfaction they get from overcoming the problems, while others are motivated by avoiding negative consequences. Heckhausen considers the causal chains “situation-result” (the probability of achieving the result in a particular situation without the action), “action-result” (the probability of achieving the result on the basis of the action), “resultconsequence” (the result from the standpoint of importance of the impact of its consequences on the behavior).

This direction is criticized for the leading role of rational, cognitive aspects in motivation and behavior. Despite the assertion that behavior is often based on logical and rational processes, preference may in fact be given to the more “optimistic” strategies [Fischhoff B. et al. The experienced utility of expected utility approaches ... 1982]. For instance, Eccles draws attention to the irrational nature of decisionmaking. However, it is possible that behavior can be driven by more stable constructs [Eccles J.S. Gender roles and women’s achievement-related decisions . 1987; Eccles J.S, Harold R.D. Gender differences in educational and occupational patterns among the gifted ... 1992], for example by stereotypes. The factors that affect decision-making process include traits of character, temperament, attitudes, and beliefs. Among them is the “cognitive structuredness”, which determines individual differences in the analysis of information (one of the parameters is the number of indicators with the help of which the information is analyzed). Part of the population with low “cognitive structuredness” often acts stereotypically and is unable to adapt to new requirements; thus it is dependent on external circumstances (O. Harvey, D. Hunt, H. Schroder, 1961; H. Schroder, M. Driver, S. Stenfert, 1967). At the same time, the opposite population group can process information very quickly and respond to the changes flexibly (H. Krohne, 1977).

An approach associated with cognitive parameters such as self-efficacy and purpose is found in the concept of self-efficacy and selfregulation [Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. 1977; Bandura A. Self-regulation of motivation... 1988]. Only a partial connection between motivation and cognitive activity is recognized; in particular, implicit and explicit motives in combination with abilities can strengthen the motivational component, but a low level of their development does not always reduce it. The Deci and Ryan approach [Deci E.L., Ryan R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal purposes... 2000] examines the compatibility of cognitive preferences with implicit motives. Motivation is characterized as a consequence of the correlation of external goals with motives; if there is no such correlation, then an important role is given to the volitional mechanisms of regulation.

The cognitive model of motivation [Lawler E.E. Pay and organizational effectiveness ... 1971; Lawler E.E., Jenkins G.D. Strategic reward systems . 1992] introduces the concept of remuneration, which can activate explicit motives that affect, for example, the choice of a job [Srivastava A. et al. Money and subjective well-being ... 2001]. In some cases remuneration may lead to conflicts between explicit and implicit motives; this requires “volitional regulation”. Accordingly, social incentives can have not only positive but also negative effects on behavior. Negative impact is due to the activation of new goals that make the initial implicit motives “ineffective” [Kanfer R. Motivation theory and industrial and organizational psychology . 1990]. When consistency is achieved between the original and new motives, then we can get a positive impact on motivation.

Taking into account the provisions of the cognitive model of motivation, in which remuneration is considered from the standpoint of the stimulus that affects behavior (employment, work, the probability of dismissal, etc.), as well as the provisions of the behavioral approach (in particular, the incentive-reactive theories), we illustrate the impact of the financial factor on various aspects of employment and labor activity of the population on the example of the monitoring of the labor potential of the Vologda Oblast residents; the monitoring was conducted

Table 2. Distribution of answers to the question: “Do you have the desire and opportunity to work?”, % of respondents

|

Answer |

Description of monetary income |

||||

|

I have enough money to afford everything I need |

I can buy the majority of durable goods without trouble, but I can’t afford to buy a car at the moment |

I have enough money to buy the necessary food and clothing, but larger purchases have to be postponed |

I have enough money only to buy food |

I don’t have enough money even to buy food, I have to get into debt |

|

|

1. Yes, I already have a job. |

76.6 |

89.6 |

83.9 |

73.4 |

52.0 |

|

2. Yes, I’m looking for a job, I’m registered with the employment service, and I’m ready to start working. |

6.4 |

2.2 |

3.0 |

10.9 |

22.7 |

|

3. Yes, I want to work, I’m looking for a job, but I’m not ready to start working yet. |

0.0 |

1.5 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

5.3 |

|

4. Yes, I want to work, but I’m not looking for a job. |

2.1 |

3.0 |

4.7 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

|

5. No, I don’t have the desire and ability to work. |

14.9 |

3.7 |

5.6 |

8.7 |

16.0 |

|

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Note: χ 2 = 95.943, р < 0.001.

The obtained value of χ 2 95.943 exceeds the critical value (26.3 at the level of error p=0.05, 32.0 at p=0.01, 39.25 at p=0.001), respectively, the null hypothesis of the absence of a correlation between the signs is rejected (the correlation between them exists).

Source: the monitoring of the quality of labor potential of the population, 2016, VolRC RAS.

by Vologda Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 20161.

The actual results show that there is a connection between people’s cash incomes and their employment status (the estimated value % 2 exceeds the critical value; see the note to Table 2). Only half of the poor have jobs, while in the group with incomes that allow them to purchase durable goods – over 90% (Tab. 2) .

Unfair payroll is seen as one of the factors impeding the implementation of one’s potential; another factor is the lack of professional knowledge. The poor and youth are more likely to point out the former, while the more well-off and people over 30 – the latter. For employees with higher education and for those who have enough money to afford everything they need, another obstacle to the realization of labor potential, in addition to the already mentioned, is the inability to influence the management of the company they work for, and for the population with secondary vocational education and with low incomes – inconvenient working hours.

Financial factor also has a significant impact on the mobility of personnel; in almost half of the cases, people change their place of employment because of low wages; this is even more important for young people (61% of cases). Almost every fourth woman and every fifth of the respondents over 30 said they had no other choice but to look for another job because

|

Answer |

Sex |

Age |

||||

|

Men |

Women |

Criterion χ 2 |

Under 30 |

Over 30 |

Criterion χ 2 |

|

|

1. Low wages |

54.8 |

50.6 |

1.402 (р = 0.236) |

61.4 |

49.3 |

9.300 (р = 0.002) |

|

2. Personal circumstances |

19.9 |

24.6 |

2.532 (р = 0.112) |

17.7 |

24.1 |

3.687 (р = 0.055) |

|

3. Personnel cuts |

13.2 |

23.6 |

14.418 (р < 0.001) |

11.8 |

21.1 |

9.159 (р = 0.002) |

|

4. Uninteresting work, no hope for career growth |

18.9 |

18.8 |

0.001 (р = 0.980) |

21.8 |

17.7 |

1.774 (р = 0.183) |

|

5. Poor working conditions |

21.2 |

20.2 |

0.110 (р = 0.741) |

30.0 |

17.2 |

15.980 (р < 0.001) |

|

6. Hard work |

10.3 |

11.8 |

0.439 (р = 0.507) |

11.8 |

10.8 |

0.160 (р = 0.689) |

|

7. I wanted to start my own business |

5.9 |

5.5 |

0.060 (р = 0.807) |

5.0 |

6.0 |

0.303 (р = 0.582) |

|

8. There is no social support from the enterprise, the organization (housing, recreation, etc.) |

6.7 |

5.3 |

0.715 (р = 0.398) |

7.3 |

5.5 |

0.893 (р = 0.345) |

|

9. Expiration of the employment contract |

7.8 |

4.8 |

2.946 (р = 0.086) |

8.2 |

5.5 |

1.967 (р = 0.161) |

|

10. Fear of closure of the enterprise, organization |

3.4 |

4.3 |

0.516 (р = 0.473) |

2.7 |

4.3 |

1.057 (р = 0.304) |

|

11. Bad relations with colleagues, with administration |

3.9 |

6.7 |

3.253 (р = 0.071) |

11.4 |

3.1 |

21.523 (р < 0.001) |

Note: 1) the sum in all the columns exceeds 100% due to the fact that the answer to the question allowed for choosing several options;

2) χ 2 = 3.841 when р=0.05; χ 2 = 6.635 when р=0.01; χ 2 = 7.879 when р=0.005. Accordingly, the value allowing to reject the null hypothesis of the absence of a correlation between the features should be at least 3.841.

Source: the monitoring of the quality of labor potential of the population, 2016, VolRC RAS.

of staffing cuts. In addition, among the reasons for the change of employment, a significant role is given to personal circumstances, as well as poor working conditions (Tab. 3) .

Similar results were obtained according to the calculation of the coefficients / 2 . In particular, it is proved that age is interrelated with such reasons for changing jobs as low wages, poor working conditions and poor relations in the team and with the managers.

The above data show that there is a connection between the financial factor, the status of employment, the implementation of the accumulated potential, and the change of the place of employment. It is revealed that the motives may vary depending on what sociodemographic group respondents belong to: for example, for the more affluent, the financial factor is less important than power (the ability to influence the management of the enterprise), while for the opposite group, working hours and remuneration are more important.

Marxist approach and the theory of objectified motivation in the school of A.N. Leontiev

As we have already shown above, people’s activity results from the action of stimuli and motives associated with both the presence of a need for something and the desire for a change. These and a number of other provisions are manifested and further developed in the framework of the Marxist approach and the theoretical provisions of A.N. Leontiev. These provisions focus primarily on human activity, its development and forms. The provisions related to the formation of an image of the need resulting from the contemplation of the subject are criticized (the key problem consists in the fact that it is impossible to explain the adequacy of the subjective image of objective reality) [Marx K., Engels F. Works. Vol. 3. 1955]. Marxism considers consciousness as a secondary phenomenon, as a result of reflection of material processes, and as a relatively passive instance. Within the framework of Marxism, the problems of motivation were considered by domestic researchers in the cultural-historical psychology of development (L.S. Vygotsky) and the psychological theory of activity (S.L. Rubinshtein, A.N. Leontiev, etc.). In the former case, the attention was focused on the general methodological laws of the genesis of the individual, in the latter – on the technological aspects.

The provisions of the activity approach were developed by A.N. Leontiev, who connects activity with personality and considers it as an internal moment [Marx K., Engels F. Works. Vol. 3. 1955]. The prerequisites for the formation of the personality arise in the conditions of establishing a hierarchy of activities and motives. Activity is characterized from the perspective of the process aimed at the subject and coinciding with the individual’s motivation for activity (motive). Non-objective activity is impossible, because it is only in activity that the prerequisites of consciousness emerge and thoughts are generated; outside activity there exists only a direct sensual reflection. The need acts as an internal condition and prerequisite for activity because it is “objectified”, the subject becomes the motive, the one that motivates activity”.

Summarizing our review of theoretical approaches to the study of motivation, we note the following:

– regardless of theoretical direction, the main source of activity is the need-based condition of an individual (deviation of physiological parameters from the optimal level), and the main task is to eliminate the stress, with the use of incentives, too (encouragement/punishment), exerting both positive and negative impact on the behavior;

– the relationship between stimuli and subsequent behavior can be direct or it can be mediated by cognitive processes; it is often recognized that implicit and explicit motives, combined with abilities, can enhance the motivational component; however, in some cases, the leading role of rational and cognitive aspects in motivation and behavior is criticized (it is pointed out that decision-making may be irrational);

– the nature of behavior and the possibility of conflict situations will depend on the degree of consistency between explicit and implicit motives; there should be a correlation between external goals and motives, and if there is no such correlation, then the volitional mechanisms of regulation should be used; contradictions between motives may arise in a situation where new stimuli make ineffective initial motives and update new ones.

Taking into account the fact that the formation of a motive can be associated with both internal and external processes, we emphasize that in the latter case there is a management of motivation. For example, in a situation in which it is necessary to complete the work with “poor” content of labor that does not have “internal attractiveness”, motivation can be formed under the influence of external factors with the help of motivational-stimulating mechanism.

-

II. Motivational-stimulating mechanism

In the scientific literature there is no unambiguous interpretation of motivational-stimulating mechanism. When describing it, we often mean the unity of motive and stimulus. The latter is considered from the point of view of an external object (material objects, images of a psychologically comfortable state, etc.), which affects the behavior of an individual or a group of people, which is attractive to them, and which serves as the goal of their aspirations. The motive is associated with an internal impulse induced by the stimulus, so in the absence of real effective stimuli, the motives may not arise.

The orientation of motivation is determined by the life attitude of an individual and the possibilities of its implementation in specific conditions. Motivation serves as a form of regulation of mental processes, is expressed in a steady desire for self-realization and acts as a motivating force. Given that the motivational sphere of an individual is the inner psychological formation, it is necessary to point out that there is an ability to influence it through motivational-stimulating mechanism [Shavel S.A. Social mission of sociology . 2010].

Based on the theoretical provisions of such approaches, as the behavioral approach and A.N. Leontiev’s approach of objectified motivation, motivational-stimulating mechanism can be defined as a system of features of the subject and the conditions of activity, due to which the subject voluntarily adopts regulatory requirements (responsibilities) and mobilizes his/ her potential for successful implementation of activity.

In this case, the conditions of activity are a stimulus, and the regulatory requirements are an image of the subject. The correlation between “internal” and “external” means that these requirements are voluntarily adopted; and in turn, their comparability with the existing potential can promote the effectiveness of activity.

Taking into account the activity-based accentuation of motivational-stimulating mechanism, when developing it, it is necessary to take into account the normative nature of relations between the participants, assuming the clarity of the “rules of the game” and the possibility of their implementation in activity; the presence of socially useful stimuli available to participants of socio-economic relations, correlated with internal orientations and attitudes; the fairness of remuneration in accordance with the contribution made; the legitimacy and legality of the means used to achieve the goal. In addition, it is important to take into account specific types of activity and conditions of their implementation [Shavel S.A., Mikhailovskaya S.V. To know the society that we live in. 2014], as it sets the specifics of motivational-stimulating mechanism.

Since the present study focuses on the aspects related to the motivation for creative work activity, we pay attention to the definition of the latter. At the same time, this concept is based on labor activity, which is considered from the standpoint of not only quantitative but also qualitative characteristics of the work performed, the discipline of participants of the labor process (compliance with the rules and internal regulations, labor discipline), as well as the nature of this activity. Taking into account the last feature, labor activity can be divided into creative and non-creative [Popov A.V. Development of labor activity of the population . 2012]. In turn, creative labor activity can be characterized as a type of labor activity in which people participate in creating new ideas, improving organizational technologies, and designing new products. The involvement in innovative processes implies the existence of abilities that at the cognitive and behavioral level help develop and implement new, promising ideas in the individual activity of the subject and in the activity of the social system within which the subject operates [Yagolkovskiy S.R. Creative activity within the innovative process ... 2013], and solve the problems contributing to the increase of the quantitative and qualitative results of the work [Bogdanchikov T. V. Labor and creative activity of employees in entrepreneurship . 2006].

It is noted in the scientific literature that creative activity involves not only thought processes, but also “dynamic forces” that put these processes into action [Gutman H. The biological roots of creativity. 1967]. However, there are different views on dynamic forces. In particular, the motivators for such actions are as follows:

– natural instinct (the urge to creativity arises instinctively; motivation for creativity is self-conscious and self-developing [Rorbach M.A. La pensee vivante. Regles et techniques de la pensee creatice . 1959]);

– communicative motive (orientation on social order, accuracy and perfection of form) [Zhabitskaya L.G. Revisiting the problem of leading motives ... 1983];

– cognitive need (formation of value attitude to the world; diversity of interests creates conditions for the accumulation of material for creative transformation, which is accompanied by the formation of the state of interest);

– achievement motive (the desire to succeed, to achieve the goal; Chambers, 1967);

– competition (competitive relationships between different creative structures can lead to discoveries and different achievements; J. Watson, 1968);

– change of the directions of creative activity (to maintain motivation for creative activity throughout life);

– pleasure from work (satisfaction from understanding complex issues and subjects; Ch. Darwin, 1957).

Let us illustrate the influence of some of the above motives on creative activity on the example of factual data. Young people under the age of 29, since they have the greatest innovative potential, were chosen as the object of research. The results obtained in 2016 in the framework of the monitoring of the quality of labor potential conducted by Vologda Research Center of RAS indicate the prevalence of forced motives for creative activity among young people (practical necessity or an order from their seniors – 46%); only 5% are engaged in creativity on a voluntary basis. One of the features of creative young people in comparison with the rest of the population is that they more often express motives for self-development and self-realization. This is manifested in the fact that among the creative youth the intellectual level is higher (71% vs. 33%), they are more often disposed toward creative work (65% vs. 8%) and entrepreneurial activity (52% vs. 25%). In addition, in the set of motives of this group an important place is given to the social motives associated with the achievement of a certain position in society and career. For example, there are three times more specialists with higher qualification among creative young people, and in the future, in fifteen years, they are twice as often, compared to the rest, see themselves as heads of enterprises, and three times more often see themselves as heads of the lower levels of management. It is not surprising that the inclination toward lifelong learning, self-development and achievement of a certain social status can be accompanied by a growth not only in productivity and average monthly wages, but also in life satisfaction. This is clearly demonstrated by the data of the monitoring of the quality of labor potential of Vologda Oblast residents for 2016: among the innovation-active youth, labor productivity is slightly higher compared to the rest (7.9 against 7.7 points on a 10-point scale), wages (18,635 rubles vs. 18,113 rubles) and life satisfaction (42% vs. 26%) are also higher.

However, it should be borne in mind that the implementation of creative activity is hampered by many factors. In the scientific literature, such factors are divided into internal (insufficient development of volitional qualities; lack of talent, knowledge; impatience, inattention) and external (insufficient level of financial security; lack of support from relatives, teachers, and parents; lack of likeminded people, etc.; M.M. Zherdeva, 2005). In a generalize form, the barriers that inhibit activity are structured by V.M. Voskoboinikov

[Voskoboinikov V.M. How to identify and develop the child’s abilities . 1996]: they include contrasuggestive (prejudice, lack of confidence in their own strength, distrust of colleagues, rigidity of beliefs and attitudes, opportunism), thesaurus-based (low level of education and/ or intellectual development, lack of access to information), interactional (the inability to plan and organize one’s own activity and that of other people) – i.e. those barriers which are sensory-emotional, cognitive, and behavioral in nature and which influence different facets of the subjectivity of an individual.

Socio-economic environment is an important factor influencing creative labor activity. At the same time, there may be not only the influence of creative people on the development of the economy of a particular territory, but also vice versa. An example of the influence of creative workers on the economy of a territory can be found in the UK, where creative industry has become one of the priorities of economic development. Already in 1998, in accordance with Creative Industries Mapping Document, 1.4 million people were employed in this sector, their total income exceeded 60 billion GBP, and their contribution to GDP was about 4%. An interesting fact is that the sphere of creative work in the UK is considered an important economic segment and a means of social mobility [Kuleva M.I. Transformation of creative employment in modern Russia . 2017].

[Aleksandrova E.A., Verkhovskaya O.R. Motivation of entrepreneurial activity ... 2016].

Of interest is the nature of the impact of the level of economic development of the territories on the motives of entrepreneurial activity. Thus, as the economic development is progressing, the level of forced entrepreneurship decreases, while the level of voluntary entrepreneurship, on the contrary, increases. For example, in 2016, the average share of voluntary entrepreneurs in innovation-oriented economies was 79%, while in resource-oriented economies it was 66%. In Russia, the largest share of forced entrepreneurs (39%) was recorded in 2014 during the crisis in the economy, when there was a reduction in demand in the labor market, accompanied by a choice in favor of entrepreneurship as an alternative to employment [ Global Entrepreneurship Monitor ... 2017].

Many different factors that affect creative work activity, lead to the need to manage it. Summing up the existing practices, we can note at least two management approaches. The first one is related to the initiative of managers along with the passivity of their subordinates and their loyalty to the leadership. In such circumstances, a significant proportion of employees often exhibit a positive attitude toward their managers and comply with their requirements [Efendiev A.G. et al. Organizational culture as a normative-role system of requirements... 2012]. In some cases, it is noted that the Russian culture involves not so much the compliance with formal aspects as the formation of relations in the team and the achievement of trust. In such conditions, there is practically no place for initiative and creativity, and career development is provided mainly through loyalty to the team [Efendiev A.G., Balabanova E.S. “Human dimension” of Russian business...2012; Efendiev A.G. et al. Careers at Russian business organizations... 2011]. The second approach to management, used in conditions of instability (increased degree of uncertainty, unpredictability of the nature of work, etc.), is associated with the provision of some autonomy to the performers, under the condition that the tasks will be implemented [Prokhorov A.P. Russian model of management. 2013]. In this model, the factors that determine career growth of employees no longer include loyalty, but professionalism, diligence and activity. Career promotion is provided in the conditions of development of individual qualities, including, for example, communication skills, creativity, high adaptability, etc. [Efendiev A.G. et al. Careers at Russian business organizations... 2011]. It is noted that in this approach, top managers often tend to involve their subordinates in the discussion of innovations and decision-making. The above approaches to management do not exist in isolation, and they may often be combined in different proportions depending on how the style and nature of work changes in the light of external conditions. According to A.P. Prokhorov, it is necessary to take into account the dualism of national character, which implies, on the one hand, passivity and a tendency to laziness, on the other hand – “vast achievements” in a short time [Prokhorov A.P. Russian model of management. 2013].

The two approaches to management are applied in the case when we are talking about the management of creative labor activity. We recognize the need to make algorithms, develop techniques contributing to the creation of something new; and at the same time to use indirect methods of control, involving the establishment of conditions for creative activity (creative environment in a research team; situations conducive to “grasping” intuitively the ideas of the project. [Ponomarev Ya.A. Psychology of creativity . 1976].

Creative teams can be managed with the help of various techniques, which can include brainstorming, synectics, maieutics, IPID (induction of psycho-intellectual activity), etc., an overview of which is given in the book by G. Bush [Bush G.O. Basics of heuristics for inventors. 1977]. According to Ya.A. Ponomarev [Ponomarev Ya.A. Psychology of creativity. 1976], such techniques are criticized because they do not go beyond the empirical (“raw material” for subsequent fundamental analysis), arise mainly outside the scientific research into creativity, and are associated with artificial ways of organizing creative communication. Therefore, their use is not always accompanied by the results that were expected to be achieved initially.

One of the ways to manage creative work activity is to assemble creative teams, especially interdisciplinary ones, which would take into account different types of personality, and which would have no barriers of isolation that complicate the generation and use of ideas [Sovetova O.S. Innovation: theory and practice . 1997]. However, the existence of such teams is associated with a number of problems, among them – understanding (due to the lack of a common language for all). Ya.A. Ponomarev and Ch.M. Gadzhiev [Ponomarev Ya. A., Gadzhiev Ch.M. Psychological mechanism of group (collective) creative problem solving . 1983] note a number of stages that creative communication must go through: if at the initial stage information is transmitted and no secondary information is intended, then one of the last stages focuses on the expression and understanding of new ideas, and the transfer of the rest of the information becomes less important. We should emphasize that the formulation and understanding of new ideas, unlike other stages in the development of communicative process, can be associated with a number of difficulties, among which a special place is given to the psychological barriers of an individual, associated with the inertia of attitudes and stereotypes of thinking (the need to understand and accept new ideas, which in some cases are contrary to conventional ideas).

Involvement in various social situations increases internal motivation to the growth of creative potential [Amabile T.M. Creativity in context. 1996]. One distinguishes between internally and externally driven motivation. In case of the former, the innovator focuses on the creative process, in case of the latter – on the results. Motivation caused by internal processes may be associated with training, acquisition of knowledge, skills, experience, while external motivation can be associated with production goals [Kaufman J.C. Creativity. 2009; Nicholls J.G. Quality and equality in intellectual development... 1979].

Motivation driven by the social aspects, involves the desire to spend one’s efforts to support and help others [Batson C.D. Prosocial motivation ... 1987; Grant A.M., Berry J. The necessity of others is the mother of invention ... 2011]. Thus, creativity based on social and moral values is considered as an “attribute” of helping other people and society as a whole [Niu W., Sternberg R.J. Contemporary studies on the concept of creativity ... 2002; Niu W., Sternberg X. The philosophical roots of western and eastern concepts of creativity . 2006]. It is revealed that creativity is directly connected with values of universalism, benevolence, good for others [Dollinger S.J., Burke P.A., Gump N.W. Creativity and values . 2007]. It is shown that the originality of the product created for others exceeds the originality of its creation for the self [Polman E., Emich K.J. Decisions for others are more creative than decisions for the self . 2011], which may be partly due to the positive influence of social motives on creative thinking [Grant A.M., Berry J. The necessity of others is the mother of invention ... 2011]. However, there are studies that show that creativity can be accompanied by social exclusion and disapproval [Arndt J. et al. Creativity and terror management ... 1999] and this, in turn, prevents creative endeavors because of the threat of destruction of social ties. Accordingly, in order to increase creative activity, measures should be taken to restore social contacts [Routledge C. et al. The life and death of creativity ... 2008].

Foreign works propose measures of “prosocial” and “altruistic” behavior [Carlo G., Randall B.A. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents . 2002; Chadwick R.A. et al. An index of specific behaviors in the moral domain . 2006; Rushton J.P. et al. The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale . 1981]. However, there are still not enough works that address social motives and behavior in the context of creativity. In particular, D.K. Simonton [Simonton D.K. Creativity . 2005] emphasizes the need to develop new methods to enhance both individual and group creativity. The majority of empirical work focus on cognitive approaches that provide creative thinking [Scott G. et al. The effectiveness of creativity training ... 2004], while motivational approaches that help overcome negative consequences of the influence of external incentives are not given due attention [Hennessey B.A., Zbikowski S.M. Immunizing children against the negative effects of reward ... 1993].

It can be stated that in order to ensure the systematic nature of creative labor activity management, it is necessary to take into account both external and internal factors, as well as to identify barriers that have a sensual, emotional, cognitive and behavioral nature and affect different aspects of the subjectivity of an individual. A combination of direct and indirect management should play a special role. On the basis of the activity approach, we can argue that significant importance should be attached to creative teams, to the interrelation of motives of their members with the priority of social motives that unite the team.

Considering the necessity of taking into account both external and internal elements of motivation in the motivational mechanism and in accordance with the external and internal forms of stimulation, we note that researchers in some cases emphasize the incentives and results, while the motivational characteristics of an individual (attitudes, beliefs, ideals)

are not reflected properly. The latter should not be ignored, because beliefs, for instance, lead to action in accordance with value orientations, and attitudes provide for targeted and consistent implementation of activity. The need to take into account both external and internal elements of motivation is due to the use of integrated approach that involves the unity of motive and stimulus. In practice, this idea is sometimes expressed in the consideration of “economic”, external, and “non-economic”, internal components. At the same time, the interdependence of the “external” and the “internal” can be achieved through the use of different forms of influence on the motivational characteristics of an individual. They include non-mandatory forms (request, offer/advice, persuasion and suggestion), direct imperative forms (orders, demands, coercion), manipulation (indirect inducement of the recipient to change the attitude toward something, to make a decision, and to do something that is necessary to achieve the manipulator’s own goals), and motivation caused by the object’s attractiveness.

In conclusion we note the following.

-

1. Our study shows that people’s behavior is determined by the features of its motivational sphere such as consistency between different groups of motives, correlation between external goals and motives (the basis of behavior is the motive that will ensure the most effective achievement of the target state), and the use of volitional mechanisms of regulation for their coordination. The motivational sphere should be based on the premise of the unity of stimulus and motive, on the possibility of structuring motives according to a number of features (explicit/implicit, economic/non-economic, formed under the decisive influence of the external environment or based on internal prerequisites, etc.).

-

2. Having analyzed the actual data, we find out prevailing motives for creative labor activity in the structure of young people’s motives; these

-

3. We determine that people’s creative labor activity should be managed on the basis of the system approach that involves the formation of creative labor activity mechanism; it should be based on the theoretical provisions of the behavioral approach and Leontiev’s objectified motivation; and its structure, along with the subject and the object, should include individual and group forms of innovation process, direct and indirect management methods, and external and internal factors that contribute to and hinder creativity.

-

4. Managing creative labor activity should be based on both the initiative on the part of managers, and on granting some autonomy to executors in solving problems; in such a case, professionalism, diligence and activity may be crucial factors, rather than just loyalty to management. One of the ways to manage creative labor activity is to assemble creative teams, which would take into account different types of individuals, coordinate goals and attitudes of its participants, and overcome the barriers that impede the generation and use of ideas.

prevailing motives include forced motives (caused by practical necessity) and economic motives (labor remuneration, justice/injustice of its calculation that affects the behavior of individuals at all stages – from employment to changing the job and dismissal). We prove that creative people, in comparison with those who are not active in this regard, have clear motives for intellectual development and selfrealization and social motives associated with the achievement of a certain position in society. We show that the motives vary depending on the fact which socio-demographic group an individual belongs to (for example, one of the most significant motives for wealthy people is their ability to manage the organization; while the less affluent attach importance not only to the financial factor but also to working hours); and these features must be taken into account in managing creative labor activity.

Список литературы Theoretical approaches to studying people's motivation for creative labor activity in the socio-humanitarian thought

- Tether B., Mina A., Consoli D., Gagliardi D. A literature review on skills and innovation. How does successful innovation impact on the demand for skills and how do skills drive innovation? CRIC report for the Department of trade and Industry, 2005.

- Dessler G. Human Resource Management. 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003.

- Raznodezhina E.N., Krasnikov I.V. Motivatsiya rynochnoi organizatsii truda v sovremennykh usloviyakh . Ulyanovsk: UlGTU, 2011. 214 p.

- Skripnichenko L.S. The study of work motivation specifics in enterprises of food industry. Innovatsionnaya nauka: mezhdunarodnyi nauchnyi zhurnal=Innovation Science: International Scientific Journal, 2015, no. 9, pp. 288-290..

- Kehr H.M. Integrating implicit motives, explicit motives, and perceived abilities: the compensatory model of work motivation and volition. Academy of Management Review 2004, vol. 29, no. 3, рр. 479-499.

- Brunstein J.C., Schultheiss O.C., Gra¨ssmann R. Personal goals and emotional well-being: The moderating role of motive dispositions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1998, vol. 75, рp. 494-508.

- Emmons R.A., McAdams D.P. Personal strivings and motive dispositions: Exploring the links. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1991, vol. 17, рp. 648-654.

- McClelland D.C., Koestner R., Weinberger J. How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 1989, vol. 96, рp. 690-702.

- Spangler W.D. Validity of questionnaire and TAT measures of need for achievement: Two meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 1992, vol. 112, рp.140-154.

- Russell I.L. Motivation. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown Company, 1971.

- Yorks L. A Radical Approach to Job Enrichment. New York: Amacom, 1976.

- Kast F.E., Rosenzweig J.E. Organization and Management: A Systems and Contingency Approach. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1970.

- Major psychological theories of motivation. Rationalistic and irrationalistic approaches to the essence and origin of motivation. Available at: http://www.newpsyholog.ru/newlos-45-2.html..

- Leontiev D.A. (Ed.). Sovremennaya psikhologiya motivatsii . Moscow: Smysl, 2002. Pp. 36-37.

- Weinberger J., McClelland D.C. Cognitive versus traditional motivational models: irreconcilable or complementary? In: Higgins E.T., Sorrentino R.M. (Eds.). Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior. Vol. 2. New York: Guilford Press, 1990. Pp. 562-597.

- Koestner R., Weinberger J., McClelland D.C. Task-intrinsic and social-extrinsic sources of arousal for motives assessed in fantasy and self-report. Journal of Personality, 1991, vol. 59, рp. 57-82.

- McClelland D.C. Scientific psychology as a social enterprise. Working paper. Boston University, 1995.

- McClelland D.C. How motives, skills, and values determine what people do. American Psychologist, 1985, vol. 40, рp. 812-825.

- Maslow A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 1943, vol. 50, рp. 370-396.

- McClelland D.C., Atkinson J.W., Clark R.A., Lowell E.L. The Achievement Motive. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1953.

- Atkinson J.W. An Introduction to Motivation. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand, 1964.

- Higgins E.T. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 1998, vol. 30, рp. 1-46.

- Kanfer R., Heggestad E.D. Motivational traits and skills: A person-centered approach to work motivation. Research in Organizational Behavior, 1997, vol. 19, pр. 1-56.

- Epstein S. Personal control from the perspective of cognitive-experiential self-theory. In: Kofta M., Weary G., Sedek G. (Eds.). Personal Control in Action: Cognitive and Motivational Mechanisms. New York: Plenum Press, 1998. Pp. 5-26.

- Metcalfe J., Mischel W. A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 1999, no. 106, pр. 3-19.

- Cantor N., Blanton H. Effortful pursuit of personal goals in daily life. In: Bargh J. A., Gollwitzer P.M. (Eds.). The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior. New York: Guilford Press, 1996. Pp. 338-359.

- King L.A. Wishes, motives, goals, and personal memories: Relations of measures of human motivation. Journal of Personality, 1995, vol. 63, pp. 985-1007.

- Sokolowski K., Schmalt H.-D., Langens T.A., Puca R.M. Assessing achievement, affiliation, and power motives all at once: The multi-motive grid (MMG). Journal of Personality Assessment, 2000, vol. 74, pp. 126-145.

- Sheldon K.M., Kasser T. Coherence and congruence: Two aspects of personality integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1995, vol. 68, pp. 531-543.

- Bazerman M.H., Tenbrunsel A.E., Wade-Benzoni K. Negotiating with yourself and losing: Making decisions with competing internal preferences. Academy of Management Review, 1998, vol. 23, pp. 225-241.

- Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 2000, vol. 55, pp. 68-78.

- Heckhausen H. Hoffnung und Furcht in der Leistungsmotivation. Meisenheim am Glan: Anton Hain, 1963.

- Fischhoff B., Goitein B., Shapira Z. The experienced utility of expected utility approaches. In: Feather N.T. (Ed.). Expectations and Actions: Expectancy-Value Models in Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1982. Pp. 315-339.

- Eccles J.S. Gender roles and women’s achievement-related decisions. Psychol. Women Q., 1987, vol. 11, pp. 135-172.

- Eccles J.S., Harold R.D. Gender differences in educational and occupational patterns among the gifted. In: Colangelo N., Assouline S.G., Ambroson D.L. (Eds.). Talent Development: Proceedings from the 1991 Henry B. and Jocelyn Wallace National Research Symposium on Talent Development. Unionville, NY: Trillium Press, 1992.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 1977, vol. 84, pp. 191-215.

- Bandura A. Self-regulation of motivation and action through goal systems. In: Hamilton V., Bower G.H., Frijda N.H. (Eds.). Cognitive Perspectives on Emotion and Motivation. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer, 1988. Pp. 37-61.

- Deci E.L., Ryan R.M. The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 2000, vol. 11, pp. 227-268.

- Lawler E.E. Pay and Organizational Effectiveness: A Psychological View. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971.

- Lawler E.E., Jenkins G.D. Strategic reward systems. In: Dunnette M.D., Hough L.M. (Eds.). Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1992. Pp. 1009-1055.

- Srivastava A., Locke E.A., Bartol K.M. Money and subjective well-being: It’s not the money, it’s the motives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2001, vol. 80, pp. 959-971.

- Kanfer R. Motivation theory and industrial and organizational psychology. In: Dunnette M.D., Hough L.M. (Eds.). Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1990. Pp. 75-170.

- Marks K., Engels F. Sochineniya . Vol. 3. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo politicheskoi literatury, 1955.

- Shavel’ S.A. Motivational-stimulating mechanism of social activity. In: Obshchestvennaya missiya sotsiologii . Minsk: Belaruskaya navuka, 2010. 404 p..

- To know the society that we live in: an interview with Professor S.A. Shavel, Doc.Sci. (Sociol.). Sotsiologiya=Sociology, 2014, no. 2, pp. 5-15.

- Popov A.V. Development of labor activity of the population. Problemy razvitiya territorii=Problems of territory’s development, 2012, no. 6 (62), pp. 66-76.

- Yagolkovskiy S.R. Creative activity within the innovative process: cognitive and group aspects. Psikhologiya: zhurnal Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki=Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 2013, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 98-108..

- Bogdanchikova T.V. Labor and creative activity of employees in entrepreneurship. Omskii nauchnyi vestnik=Omsk Scientific Bulletin, 2006, no. 4 (38), pp. 181-184..

- Gutman H. The biological roots of creativity. In: Exploration in Creativity. New York, 1967.

- Rorbach M.A. La pensee vivante. Regles et techniques de la pensee creatice. Paris. 1959.

- Zhabitskaya L.G. Revisiting the problem of leading motives for literary and artistic creativity. In: Tezisy nauchnykh soobshchenii sovetskikh psikhologov k VI Vsesoyuznomu s"ezdu Obshchestva psikhologov SSSR. Lichnost’ v sisteme obshchestvennykh otnoshenii. Sotsial’no-psikhologicheskie problemy v usloviyakh razvitogo sotsialisticheskogo obshchestva . Moscow, 1983. Part 1. Pp. 116-118..

- Sharov A.S. Ogranichennyi chelovek: znachimost’, aktivnost’, refleksiya . Omsk, 2000.

- Kak opredelit’ i razvit’ sposobnosti rebenka . Compiled by V.M. Voskoboinikov. Saint Petersburg, 1996.

- Kuleva M.I. Transformation of creative employment in modern Russia: on the example of employees of non-state art centers in Moscow. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya=Public Opinion Monitoring, 2017, no. 2 (138), March-April, pp. 50-62.

- Aleksandrova E.A., Verkhovskaya O.R. Motivation of entrepreneurial activity: the role of institutional environment. Vestnik SPbGU. Ser. 8: Menedzhment=Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Management, 2016, no. 3, pp. 107-138..

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Russia 2016/2017: National Report. Available at: http://gsom.spbu.ru/files/docs/gem_russia_2016-2017.pdf..

- Efendiev A.G., Balabanova E.S., Gogoleva A.S. Organizational culture as a normative-role system of requirements to employees of Russian business organizations. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsial’noi antropologii=Journal of sociology and social anthropology, 2012, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 167-187..

- Efendiev A.G., Balabanova E.S. "Human dimension" of Russian business: towards a democratic-humanistic type of social organization of a company. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 2012, no. 7, pp. 43-54..

- Efendiev A.G., Balabanova E.S., Sorokin P.S. Careers at Russian business organizations as a social phenomenon: experience from empirical research. Mir Rossii=Universe of Russia, 2011, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 140-169..

- Prokhorov A.P. Russkaya model’ upravleniya . Moscow: Studiya Artemiya Lebedeva, 2013.

- Ponomarev Ya.A. Psikhologiya tvorchestva . Moscow, 1976.

- Bush G.O. Osnovy evristiki dlya izobretatelei . Riga, 1977.

- Sovetova O.S. Innovatsii: teoriya i praktika . Saint Petersburg, 1997.

- Ponomarev Ya.A., Gadzhiev Ch.M. Psikhologicheskii mekhanizm gruppovogo (kollektivnogo) resheniya tvorcheskikh zadach: issledovanie problem psikhologii tvorchestva . Moscow, 1983. Pp. 279-295.

- Amabile T.M. Creativity in context. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 1996.

- Kaufman J.C. Creativity 101. New York, NY: Springer, 2009.

- Nicholls J.G. Quality and equality in intellectual development: The role of motivation in education. American Psychologist, 1979, vol. 34, pp. 1071-1084 DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.11.1071

- Batson C.D. Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? In: Berkowitz L. (Ed.). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 20. New York, NY: Academic Press, 1987. Pp. 65-122 DOI: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60412-8

- Grant A.M., Berry J. The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective-taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 2011, vol. 54, pp. 73-96 DOI: 10.5465/AMJ.2011.59215085

- Niu W., Sternberg R.J. Contemporary studies on the concept of creativity: The East and the West. Journal of Creative Behavior, 2002, vol. 36, pp. 269-288 DOI: 10.1002/j.2162-6057.2002.tb01069.x

- Niu W., Sternberg X. The philosophical roots of western and eastern conceptions of creativity. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 2006, vol. 26, pp. 1001-1021 DOI: 10.1037/h0091265

- Dollinger S.J., Burke P.A., Gump N.W. Creativity and values. Creativity Research Journal, 2007, vol. 19, pp. 91-103 DOI: 10.1080/10400410701395028

- Polman E., Emich K.J. Decisions for others are more creative than decisions for the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2011, vol. 37, pp. 492-501 DOI: 10.1177/0146167211398362

- Arndt J., Greenberg J., Solomon S., Pyszczynski T., Schimel J. Creativity and terror management: Evidence that creative activity increases guilt and social projection following mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1999, vol. 77, pp. 19-32 DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.19

- Routledge C., Arndt J., Vess M., Sheldon, K.M. The life and death of creativity: The effects of mortality salience on self versus social-directed creative expression. Motivation and Emotion, 2008, vol. 32, pp. 331-338 DOI: 10.1007/s11031-008-9108-y

- Carlo G., Randall B.A. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 2002, vol. 31, pp. 31-44 DOI: 10.1023/A:1014033032440

- Chadwick R.A., Bromgard G., Bromgard I., Trafimow D. An index of specific behaviors in the moral domain. Behavior Research Methods, 2006, vol. 38, pp. 692-697 DOI: 10.3758/BF03193902

- Rushton J.P., Chrisjohn R.D., Fekken G.C. The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 1981, vol. 2, pp. 293-302 DOI: 10.1016/0191-8869(81)90084-2

- Simonton D.K. Creativity. In: Snyder C.R., Lopez S.J. (Eds.). Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005. Pp. 189-201.

- Scott G., Leritz L.E., Mumford M.D. The effectiveness of creativity training: A quantitative review. Creativity Research Journal, 2004, vol. 16, pp. 361-388 DOI: 10.1080/10400410409534549

- Hennessey B.A., Zbikowski S.M. Immunizing children against the negative effects of reward: A further examination of intrinsic motivation training techniques. Creativity Research Journal, 1993, vol. 6, pp. 297-307 DOI: 10.1080/10400419309534485