Traces of the Dahaean and Sarmatian cultural legacy in Ancient Turan and Old Rus

Автор: Suleimanov R.H.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study examines the migrations of the Dahae and Sarmatians—the two related early nomadic peoples of Middle Asia and Eastern Europe—directed to the south and west of their homeland. Archaeological, written, and folkloric sources make it possible to trace the migrations of the Dahae and Sarmatians over several centuries preceding the spread of Islam in Central Asia and of Christianity in Old Rus. The study focuses on mortuary monuments, temples, and sanctuaries, cross-shaped in plan view, of migrants and their descendants. A detailed analysis of the major southward migration of Dahae from the Lower Syr-Darya in the late 3rd to early 2nd BC is presented. This migration had a considerable effect on ethnic and cultural processes in Middle Asia. The migration aimed at conquering the lands of Alexander the Great’s descendants, who were rapidly losing control over them. Features of Dahaean culture are noticed in town planning, architecture, mortuary rites, armor, etc. over the entire territory they had captured. Southward migration of the descendants of the Dahae—people of the Kaunchi and Otrar cultures—from the Syr-Darya, led by the Huns, was part of the Great Migration. The Kaunchi people headed toward the oases of Samarkand and Kesh, the Otrar people toward the oasis of Bukhara, and those associated with the Dzhetyasar culture toward the Qarshi oasis. It is demonstrated that while the cross-shaped plan view of religious structures turned into the eight-petaled rosette, the fu neral rite did not change, remains of burials and charcoal are observed everywhere. Relics of the ScythoSarmatian legacy are seen in the culture of Old Rus. For instance, remains of the sanctuaries of Perun are walls and ditches arranged in a cruciform or eight-petaled fashion, fi lled with charcoal and bones of sacrifi ced animals, with a statue of the supreme Slavic deity, in the center. Early sanctuaries of Perun in Kiev and Khodosovichi were cruciate in plan view, while later ones on the banks of the Zbruch and the Volkhov rivers had octopetalous plans. Apparently they were infl uenced by the architectural traditions of Dahae and Sarmatians, who took part in the ethnogenetic processes in both Old Rus and Turan.

Mortuary rites, traditions, migrations, cults, archaeological cultures, ecology

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146299

IDR: 145146299 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2021.49.3.060-074

Текст статьи Traces of the Dahaean and Sarmatian cultural legacy in Ancient Turan and Old Rus

According to the tradition of the Avesta and Shahnameh, the lands of the sedentary Aryans were in the basin of the southern Amu Darya – the upper reaches of the Vakhsh – Oxus (Iran and Khorasan (from “Khors”, “Khorshid” – the Sun)), and the lands of the wandering Turs were in the basin of the Syr Darya – Tanais and the upper reaches of the Jaxartes (Turan). On the basis of archaeological evidence, it has long been established that the Syr Darya was the southern border of the steppes, and the interfluve of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya (Sogdiana) often turned out to be the region of rivalry and interaction between the cultures of the agricultural and nomadic peoples of Central Asia. Something similar happened in Eastern Europe and southern Siberia, where the southern

foothills and northern forest-steppe of the middle latitudes were separated by the so-called steppe belt.

Bounded on the northwest by the Aral Sea, the delta of the Syr Darya—a vast alluvial plain surrounded by semidesert steppe and sands of the Kyzylkum Desert—had traditional connections with Khorezm, the Volga region, and the steppes of Kazakhstan. Sedentary agricultural urbanized culture of the population inhabiting the Lower Syr Darya region emerged in the mid first millennium BC under the influence of the urbanization of Khorezm and on the basis of the cultures of the nomads who were engaged in seasonal agriculture along ancient the delta channels of the Syr Darya.

The migration of ancient societies entailed carrying the entire complex of their ethnic features, which could take root or eventually disappear under the influence of ethno-genetic processes in a new ecological and ethnocultural environment, depending on specific conditions. We know mainly about migrations in ancient periods from fragmentary information in written sources. The comprehensive analysis of burial structures and sanctuaries, as well as traces of cultic rituals, makes it possible to supplement this information and reconstruct the customs and rituals of particular peoples. In ancient times, rituals were closely associated with mythology and language. An exchange of mythological subjects, as well as religious beliefs and vocabulary, took place during the periods when migrants settled down and ethnic boundaries in certain ecological zones became stabilized. In material culture, exchange of production techniques, styles of fine art, types of weaponry, coins, etc., occurred. The emergence of a special nomadic type of cattlebreeding resulted in annual large-scale and long-term seasonal migrations as a lifestyle of population in vast expanses of the Eurasian steppes, while the formation of local cultures of the sedentary agricultural population was sometimes interrupted by new waves of nomads.

Migration of the Dahae to the south of Middle Asia

Large migration of the Dahae from the lower reaches of the Syr Darya in the late 3rd to early 2nd century BC made a great impact on the ethnic and cultural genesis of the population living in Middle Asia. Numerous but very brief reports about this event have survived in various written sources. The nomadic peoples of the steppes were heterogeneous, but had similar archaeological complexes. The Greco-Roman sources call them the Sauromates, Sirmats, and Sarmatians, although occasionally the Dahae are named among the nomads. The Chinese sources mention the Kangju land. The Persian sources inform us about the Dahae. This ethnonym in the form of daya also appears in the Greco-Roman sources. The Dahae and Sarmatians, whose movements can be traced through archaeological finds, had a similar material culture and mythology; at least the majority of them spoke similar dialects of the Eastern Iranian language group.

The Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition has established that after the defeat of Cyrus by the army of nomadic tribes and peoples led by the Massagetae by the mid first millennium BC, the Chirik-Rabat and Dzhetyasar archaeological cultures emerged in the area of the ancient delta channels of the Syr Darya. After two centuries of successful development, the Chirik-Rabat culture found itself in a crisis. The movement of tectonic plates in the Turan Depression had caused serious changes in the landscape—the hypsometric slope of the entire Eastern Aral Sea region constantly increased from south to north, which resulted in reduction of the volume of water inflow from the middle river channel into the southern channels in the ancient delta of the Syr Darya. In the 3rd century BC, the river in its lower course broke into a new northern channel and flowed from the northeast into the Aral Sea. This led to ultimate drainage in the territory of the Chirik-Rabat culture, which originated in the 5th–4th centuries BC. B.I. Weinberg reasonably considered this culture to belong to the Dahae mentioned in the written sources (1999). Specific aspects of their culture have been analyzed in a number of studies by B.I. Weinberg and L.M. Levina (Weinberg, Levina, 1993; Weinberg, 1999). The Dahae left their homeland in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya gradually, as the crisis unfolded.

The Dahae are mentioned in the Frawardin-Yasht of the Avesta, together with the Arya, Tura, Sairima, and Saina (Weinberg, 1999: 207). The appearance of the Dahae and Sairima in the same list (it does not matter whether the latter are compared with the Sauromates or Sarmatians) confirms that these peoples at that time represented independent political entities, although their material culture was very close, and the weaponry from the burials was identical. From the 4th century BC, the Dahae were known as warriors, first of the Achaemenid troops and then of the army of Alexander the Great. Genetically, the Dahae were related to the Sauromates and Sarmatians in the south of the Urals. The Ural River is the medieval Yaik and Ptolemy’s Daik. This name is related to the ethnic name of the Dahae or Daae. In the 4th–2nd centuries BC, the Dahae are mentioned among the population of the territories located south of the Amu Darya—Khorezm, Uzboy, and Atrek, as well as the Zarafshan basin. Their archaeological complex is genetically related to the Prokhorovka culture of the southern Urals (Balakhvantsev, 2016).

According to the Greco-Roman sources, the Parni, who were a part of the Dahae union, led by Arsaces and Tiridates, captured Parthia. Under Mithridates the Great, the rulers of Parthia expanded their borders to

Mesopotamia in the southwest, and exerted pressure on the Kushans in the east; in the north, they owned the lands up to Turiva – Tarab and Kazbion – Kaspi on the southwestern frontiers of Sogd. The history of Parthia is an individual and vast topic.

After the Dahae left their homeland at the turn of the 3rd–2nd centuries BC, the life along old channels of the Kuvan Darya, Inkar Darya, and Jana Darya came to a standstill. Land cultivation began along the northern, new lower part of the river, but there were no settlements there until the 2nd century BC.

The earliest among the sites of the Chirik-Rabat culture is the Chirik-Rabat settlement in the place of the first capital of these people. It is now represented by ruins with burial structures of the leaders who lived in the 5th–4th centuries BC. The settlement is surrounded by an oval defensive wall. The Babish Molda settlement was the second in time. This was a fortress-type structure in the form of a monumental, square-shaped high fortress, surrounded by a defensive wall around the perimeter with an impregnable high tower at the entrance, which was connected to the fortress by a swing bridge. Weinberg dated the castle to the 4th century BC and believed that it was built as the seat of a satrap after incorporating the lands of the Dahae into the Empire as allies of the Achaemenids. The fortress remained unfinished, because already in the late 4th century BC, Khorezm, and with it the Dahae, gained independence. The land of the Dahae, through which large and small channels of the Syr Darya delta flowed, had been inhabited and cultivated, but in the process of the endogenous ecological disaster mentioned above, it became depopulated.

The Dahae roamed and went on campaigns in Middle Asia in the earlier time, since the 5th–4th centuries BC. This is revealed by the evidence from numerous burial grounds of the undercut and catacomb types, located in the middle reaches of the Syr Darya, Zarafshan, and in the Kyzylkum. In the Aral Sea region, the Dahae were preceded by the Saka people, related to the Sauromates (Smirnov, Petrenko, 1963: 5). Almost all scholars believe in the common origin of the Dahae and the Sarmatians, and the unity of their material culture. With all resemblance to the Scytho-Sarmatian world of the early nomads, the Dahae, who left the lower reaches of the Syr Darya in the 2nd century BC, had two hundred years of experience in sedentary agricultural, cattlebreeding and, moreover, urbanized culture, as evidenced by two hundred-year history of the Chirik-Rabat culture. The last and final movement of the Dahae to the south and east at the turn of the 3rd–2nd centuries BC became the impetus for the migration of other nomadic peoples, which swept away the last Greek rulers (the heirs of Alexander the Great) in the 2nd century BC and laid the foundation for new dynasties of autochthonous origin. It is no coincidence that the Sarmatian movement in the spaces to the west of the Aral Sea and the Urals began in the 3rd century BC.

In the south, one part of the Dahae invaded Parthia, while another part, passing Sogd and Bactria and crossing the Hindu Kush, occupied the lands up to the Helmand Valley and the middle reaches of the Indus, where the so-called Indo-Scythian or Indo-Parthian kingdoms existed in the first centuries BC. These kingdoms minted their own silver coins, from which the names of the rulers such as Vonones, Maues (Mahvash?), and Azes are known.

Roman written sources report that Bactria was taken away from the Greeks by the Asii, Pasiani, Tokhari, and Sakarauli. It may be assumed that these were the names of the main tribal unions of the Dahae. Zhang Qian paid a diplomatic visit to the Da Yuezhi, who settled in the upper reaches of the Amu Darya after being driven out by the Huns and Wusuns from Eastern Turkestan; he called the land they recently occupied “Daha”. It may be the case that the Tocharians of the Greco-Roman historical tradition correspond to the Yuezhi from the Chinese sources.

Thus, by the first century BC, a large cultural community, which occupied the territory from the lower reaches of the Volga and Ural Rivers to the lower and middle reaches of the Syr Darya, had emerged in the steppe zone of Middle Asia. In the west, it bordered with the lands of Greek colonies. This is reflected in Greek sources informing us about the arrival of the Sarmatians, who were known as the Dahae or Daae in the south of Middle Asia. Chinese sources call them “Kangju”. The population of these areas is distinguished by a common archaeological complex. Since the beginning of the Common Era, red-clay mugs with the side handle in the form of a lamb with twisted horns have been a marking feature of this cultural community (Podushkin, 2015).

These large-scale migrations and ethno-cultural processes resulted in profound changes in the material and spiritual culture of the population living in Middle Asia. These changes are reflected primarily in the monetary economy of this vast region. After new rulers of each separate possession declared their sovereignty, they began to mint coins in their own names. Not all rulers had an opportunity to issue full-fledged silver coins, but they tried to adhere to the weight and nominal standards of the Greek drachma and chalkos whenever possible. In most possessions, with the exception of the Parthian State, coins quickly lost their weight and quality, and silvered drachmas appeared. Coins vary in typology; all copper coins are imitations of Greek coins of various types. The new thing was that the clan tamgas of the rulers appeared on the coins, while the image of a deified ancestor, often on horseback, was represented on the reverse. These are already the undoubted symbolic features of the sovereignty of the nomads.

Initially, the Dahae (represented by their warlike clans, which were inclined to nomadism) occupied the vast fragmented territories of the heirs of the Empire; but over time, when the last wave of migrants had left the lands in the middle reaches of the Syr Darya, which their ancestors had developed, the Dahae began to populate these lands. This was also an exodus from the homeland by those communities of the Dahae who had long been sedentary and were engaged in sophisticated cattle-breeding and agricultural economy. They moved upstream the Syr Darya along the right bank, which was partially irrigated by small rivers running down from the southern slopes of the Karatau Ridge. In the process of slow migration, these Dahae communities began to appropriate the lands suitable for agriculture. Later, some of the Dahae went to Semirechye, as indicated by the pottery complexes of the first half of the first millennium BC discovered there. As a result, two new ethno-cultural communities represented by the Otrar-Karataus and Kaunchi archaeological cultures well-studied for a long time, emerged in the basin of the middle reaches of the Syr Darya in the 2nd century BC. The groups of the Dahae who settled in Semirechye spread their original early urban culture to the right bank of the Syr Darya. In the 2nd–1st centuries BC, the founding of large and small towns such as Sygnakh, Sauran, Yassi (Turkestan), Otrar, Chimkent, Tashkent, and Taraz, as well as fortified settlements located between them, took place. The evidence of long-term excavations carried out in Tashkent, Chimkent, and Taraz has confirmed their age of over two thousand years.

These movements were fundamentally different from the previous movements of the nomadic Dahae, which corresponded to the traditional model of nomadic migration. Now the Dahae became united and, thanks to their mobility and military superiority and despite their small numbers, they captured wealthy but defenseless agricultural areas in order to receive tribute. In this case, the Dahae acted as occupiers; in the role of new lords, their aristocracy infiltrated the urban centers of the conquered territories.

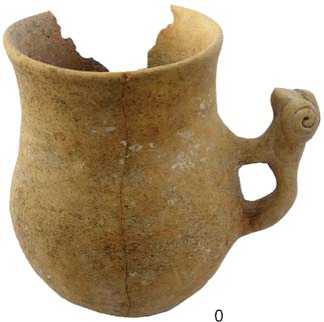

Wherever the Dahae appeared, they left the signs of their culture, manifested in urban planning and architecture, funeral rites and weaponry, and art and religious traditions. At the same time, the material culture of the Dahae retained the features inherent not only in the Prokhorovka culture, but also in the Sarmatian culture of Eastern Europe. This has been observed by the researchers of burial mounds in the valley of the Syr Darya and Zarafshan, and on the right bank of the Amu Darya (Yagodin, 1982; Podushkin, 2015). Sarmatian mugs with the lamb-shaped handle are also typical of the Kaunchi culture of the Tashkent oasis of the 1st–4th centuries AD (Fig. 1).

In my opinion, the emergence of the Chirik-Rabat and Prokhorovka cultures happened not only synchronously, but also syngenetically: the carriers of both archaeological

Fig. 1. Mug with the lamb-shaped handle. 2nd–3rd centuries AD. Yangiyul (URL: .

5 cm

cultures constituted the union of the Dahae. In the 3rd century BC, owing to the drying up of their oasis in the delta of the Syr Darya, all Dahae were set in motion, and some of them entered the territory of the Sauromates. After merging with the newcomers, the Sauromates could have begun to be called “Sarmatians”.

The influence of the Dahae on the urban planning and culture of Sogd is also manifested in Nakhshab, in the lower reaches of the Kashkadarya. A new grand fortified town of the fortress type Qal’ayi Zahhoki Moron—the Castle of Zahhak the Snake (Dahak)—was built 10 km south of the capital fortified settlement of Yerkurgan in the 2nd century BC. It was a colossal square fortress with 100-meter long sides and height exceeding 15 m; it was surrounded by three rows of walls: the first row measured 210 × 210 m; the second 400 × 400 m, and the third 1500 × 1500 m (its walls have not survived). Walls up to 8 m high and up to 10 m wide at the base have been preserved. Previously, there were such structures neither in Sogd nor in Bactria. Qal’ayi Zahhoki Moron reproduces all the fortification features of Babish Molda— an unfinished residence of the 4th century BC, belonging to the Satrap of the Dahae in the Aral Sea region, in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya—but has exaggeratedly enlarged sizes and three times as many walls. The fortress and second row of walls in Qal’ayi Zahhoki Moron on its southern façade have massive protrusions similar to the Babish Molda gatehouse. It can be assumed that precisely this fortress town of the Dahae was the center of power for the new lords of the land. The very name Zahhak or Dahak indicates its connection with the ethnic name of the Dahae. Judging by the grand sizes of Qal’ayi Zahhoki Moron, the power of the owners of the new Dahae residence in Nakhshab extended far beyond the boundaries of Nakhshab proper and Sogd. The formerly

Hellenized capital of Nakhshab (the fortified settlement of Yerkurgan) might have been assigned the role of the trading and artisanal center of the oasis. It is important to mention that the settlement of Kat was located in the fortified settlement before the latter was consumed by the modern town of Qarshi; old-timers remembered this still in the second half of the 20th century. Kat is a traditional name of towns and fortifications of the Eastern Aral region, including the name of the capital town and Early Medieval Khorezm; most likely, the word is associated with the Dahae language.

The construction of such large ancient towns of the Fergana Valley as Akhsikath and others happened at that same time.

In addition to the fortress center Qal’ayi Zahhoki Moron, a monumental Zoroastrian Tower of Silence was built outside the walls of the Yerkurgan settlement in ancient Nakhshab (the Qarshi oasis). The town was surrounded by a second outer wall with semicircular flanking towers. The Tower, which turned out to be inside the town wall, was mured up.

The town of Samarkand under the Dahae was going through hard times; at that time, less than half of its area was inhabited. Small fortified towns with citadels were built in the Samarkand, Bukhara, and Kesh oases (Poykent, Varakhsha, Dabusia, Kitab, etc.), in the Fergana Valley, and in the south of Kazakhstan.

In the 2nd–1st centuries BC, on the lands newly captured by the Dahae, temple structures of previously unknown types were built: in the form of a large cross in plan view, with rooms inside, surrounded by a wall rounded or square in plan view.

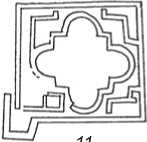

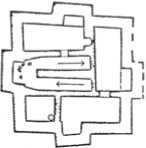

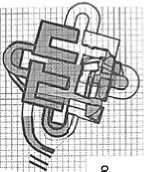

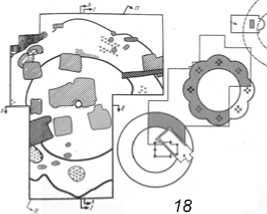

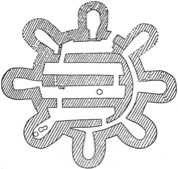

A classic example of such a religious complex is the oldest temple complex—Shashtepa, of the 2nd century BC in Tashkent. The structures Arktepe and Bilovurtepa in the Fergana Valley of the same period, as well as the Early Parthian Shahr-i Qumis VII and Shahr-i Qumis XIII in northeastern Iran, have a similar layout. All of these bear traces of cultic and commemorative rituals that go back to the rituals of the Eastern Aral Sea region and burial rites of the Sarmatians. The Early Scythian mausoleums at the cemetery of Northern Tagisken and the Chirik-Rabat culture in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya reveal various combinations of a cross, circle, and square in their planning. However, outside their homeland, the Dahae continued to reproduce only one layout model of their commemorative structures in a form of a cross surrounded by a round or square wall (Fig. 2).

In the early first millennium AD, a religious building of the cruciform layout with four towers was built one parasang upstream of the Salar River, on the site of the settlement of Minguryuk (the territory of Tashkent). The towers are not rectangular, as is the case with the buildings in Shashtepa, but semicircular; because of that, the structure had the form of a four-petaled rosette in plan view (Filanovich, 2010: 131ff). During the transition period from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages, this model for religious buildings was widespread in Middle Asia. Referring to G.V. Grigoriev and A.I. Terenozhkina, who discovered the Kaunchi culture, M.I. Filanovich wrote that the pottery of the Kaunchi stage 2 (1st–2nd centuries AD) with mugs with handles of horned lamb was similar to Sarmatian pottery. Kaunchi 3 or the Dzhun culture dates back to the time of the Hunnic movement (3rd–5th centuries AD), while the pottery of Kaunchi 1 shows parallels with the pottery of the Chirik-Rabat culture (Filanovich, 1983: 112).

A burial of the leader dressed in laminar steel armor was discovered by S.P. Tolstov in the center of the Chirik-Rabat settlement. Such armor is associated with the beginnings of the semi-sedentary early urban culture and statehood of the Dahae in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya. The discovery has made it possible to establish the origins of the famous cavalry of the cataphracts from Central Asia. Iconographic evidence clearly links this aristocratic type of warrior with the Dahae, Sarmatians, as well as with the armies of Kangju and Parthia. Images of warriors-cataphracts are represented on a belt buckle from the Orlat burial mound dated to the turn of the Common Era, which in fact are a documentary illustration of Plutarch’s narration about the cataphracts encased in iron armor and serving the Parthian leader Surena, who defeated the Roman army of Crassus. However, the horses shown on Orlat’s plates are not protected by armor, since in the vast expanses of Middle Asia there was no need for that. Mobility and speed were much more important

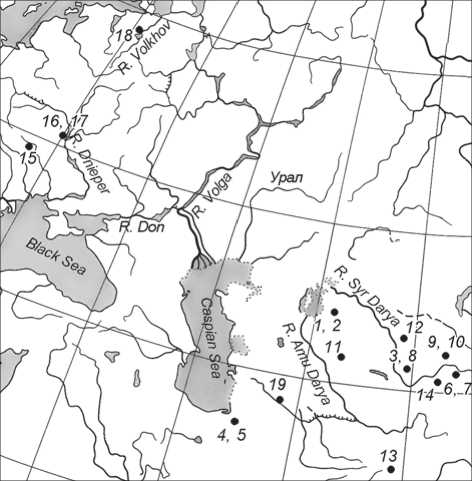

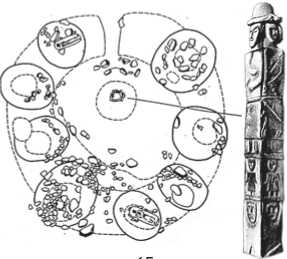

Fig. 2 . Map of pagan cultic and commemorative sites of Ancient Turan and Old Rus.

1 – mausoleums of the Northern Tagisken burial ground, 10th–8th centuries BC (after (Itina, Yablonsky, 2001)); 2 – mausoleums of the Chirik-Rabat culture of the 5th–3rd centuries BC (after (Weinberg, Levina, 1993)); 3 – Shashtepa, 2nd century BC–4th century AD (after (Filanovich, 2010)); 4 , 5 – Shahr-i Qumis, 2nd century BC–2nd century AD (after (Filanovich, 2010)); 6 – Bilovurtepe, 1st–3rd centuries AD (after (Zadneprovsky, 1985)); 7 – Ark Tepe, 1st–3rd centuries AD (after (Gorbunova, 1994)); 8 – Minguryuk, 1st–4th centuries AD (after (Filanovich, 2010)); 9 – Kzyl-Kainar-Tobe, 1st–4th centuries AD (after (Mershchiev, 1970)); 10 – Chol-Tobe, 1st–4th centuries AD (after (Mershchiev, 1970)); 11 – Setalak I, 3rd–6th centuries AD (after (Suleimanov, Mukhamedzhanov, Urakov, 1983); 12 – Kultobe, 1st–4th centuries AD (after (Smagulov, Erzhigitova, 2013)); 13 – Khair Khaneh, 5th–6th centuries AD (after (Hachkin, Carl, 1936)); 14 – Tepe-5, 3rd–6th centuries AD (after (Gorbunova, 1985)); 15 – sanctuary of Perun on Mount Bogit near the Zbruch River, the beginning of the Common Era–9th century AD (after (Rybakov, 1987; Ivanov, Toporov, 1982)); 16 – sanctuary of Perun in Kiev, 8th–10th centuries AD (after (Sedov, 1982)); 17 – sanctuary of Khodosovichi, 10th–11th centuries AD (after (Sedov, 1982)); 18 – sanctuary of Perun in Novgorod, 9th–10th centuries AD (after (Sedov, 1982)); 19 – eight-tower structure in Garry-Kyariz I, 7th–6th centuries BC (after (Pilipko, 1984)).

in the small skirmishes of steppe dwellers with each other. Armor and complex of weaponry, similar to those depicted on the Orlat buckle, also appear on the coins of the Indo-Scythian rulers, Roman bas-reliefs, and on a few iconographic finds from Parthia. Later, military armor of this type would be depicted on the coins of the rulers of the Kushan, and in Early Medieval paintings in Sogd and Eastern Turkestan.

In pottery production, the appearance of large spherical flasks flattened on the sides in the oases of Middle Asia, as well as bell-shaped goblets in Sogd and Bactria, are associated with the influence of the Dahae-Sarmatians; some specific features of the Dahae pottery are known from the evidence of the Chirik-Rabat culture. Decorating pots and jugs with streaks of brown engobe is a distinctive feature of the Dahae pottery.

Several examples of painting and sculpture from the temples of Middle Asia of the first centuries BC to the beginning of the Common Era, as well as compositions on toreutics from the famous burials of Tillya-Tepe of the 1st century BC in Northern Afghanistan, testify to the spreading cult of female deities of the tribes of the Daho-Sarmatian circle. The traditionally high position of women and mothers was undoubtedly the legacy of the earlier Sauromates, among whom the Greek sources mentioned gynecocracy. The Sauromates contributed to the emergence of the culture of both the Sarmatians and the Dahae.

The history of female deities in Central Asia is worth considering in some detail. Patriarchy had developed since the Chalcolithic in ancient agricultural societies in connection with the development of economy, accumulation of wealth, and militarization of lifestyle. In the steppe zone, this process happened more slowly—the role of women was too high in nomadic societies, since for most of the year men grazed cattle in vast steppes or participated in long military campaigns to foreign lands. The role of the woman and her cult persisted for a very long time in sophisticated cattle-breeding and agricultural societies in Central Asia, the Northern Caspian and Aral Sea regions, and the basin of the Syr Darya, Semirechye, and the foothills of Eastern Turkestan.

It is known that the patriarchal pantheon corresponds to Zoroastrianism; it included only two female characters—the goddess of water and fertility Aredvi Sura Anahita and goddess of the earth Spenta Armaiti. The main character in the pantheon was the male deity Ahura Mazda. In this respect, the pantheon of Zoroastrianism did not differ from the Greek and Roman pantheons presided over by Zeus and Jupiter, respectively. After the appropriation of the entire heritage of the Achaemenids and Alexander the Great by the early nomads in the first centuries BC, female deities returned to the cultic pedestals. Sculptural representations of female deities appeared in the urban temples of Khorezm and Bactria, in Parthia, and in the south of Sogd. Written sources report about the temple of Cybele in Samarkand. Images of Asian goddesses are rendered in the traditions of the Hellenistic art, showing a fusion of Asian goddesses with Greek imagery. However, the fact that these deities were of local origin is confirmed by the phrase of Clement of Alexandria: in Bactras, there was a statue of Aphrodite Tanais, that is, the goddess of the Syr Darya (Trever, 1940: 21).

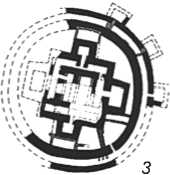

An important difference between Aphrodite and Zoroastrian Anahita was her companions—representatives of the water element: fish, dragons, snakes, and frogs. In the Zoroastrian bestiary, these were considered unclean beings from the world of evil; but in most myths of the peoples of Antiquity, these creatures were companions of aquatic female deities. Earlier, we have examined in detail the image of a female deity embodied in the sculpture of the goddess, located in the temple of Yerkurgan (the ancient capital of Southern Sogd), along with a metal figurine of a snake and an image of a frog carved of agate. An imprint of a seal of the country’s ruler was found in the same location, in potters’ quarter. The ruler is depicted sitting on a dragon with a whip in his hand, and the figure of a goddess holding out a goblet to him is represented opposite him (Fig. 3). It was the classic investiture composition typical of the proclamative art of the Ancient East and Scythia. It is possible that the image of a female deity was introduced to the oases in the basin of the Amu Darya by the Daho-Sarmatian peoples, who crushed the power of Alexander the Great’s heirs (Suleimanov, 2000: 274).

We should also discuss the image of the dragon Azhdar. According to the conclusion of A.D.H. Bivar, Azhdar or Azhi Dahaka of Avesta means the Dragon of the Dahae (Dandamaev, 1991). The mythological Azhi, Slavic Yassi, and Yashcher (Lizard), as well as Indian Ahi are associated with the water element. For the Dahae, this was the image of the sacred sturgeon—the largest

Fig. 3 . Stamp representing the investiture of a ruler. 3rd century AD. Yerkurgan (Suleimanov, 2000).

predator of the Aral-Caspian basin. It can be assumed that Astrakhan/Ashtarkhan in the north of the Caspian Sea, and Astrabad in the south had been the places of worshipping this fish since prehistoric times. A gold plaque from one of the female burials that accompanied the ruler’s burial in Tillya-Tepe in Northern Afghanistan depicts the goddess of water holding a large sturgeon in each hand (Fig. 4). Among the Dahae, the sturgeon was considered a companion of the Great Goddess of the water element, who gave life. In the territories of the Dahae remote from the sea, the sturgeon turned into the mythical dragon azhdar . In Shakhrisabz, until the 20th century, there was a cult of the grave of Saint Malik Azhdar or Ashtar. According to N.S. Nyberg, Anahita could originally have been a river nymph among the Saka people of the Syr Darya (1938: 261).

The dragon (mythical serpent and inhabitant of the three elements) is popular in the mythology of all peoples of the world. These images are of different origins. In Middle Asia, it was originally a fish. The earliest images of azhdar known from the Tillya-Tepe toreutics retain all the anatomical features of fish.

Fig. 4 . Plaque representing the goddess of water. 1st century BC. Tillya-Tepe (Sarianidi, 1985).

Migration of the Dahae descendants under the auspices of the Huns, Kidarites, and Hephthalites

The second major migration from the basin of the Syr Darya to the south happened in the 4th century BC. The migrants were distant descendants of the Dahae (the carriers of the Kaunchi and Otrar-Karatau cultures), who were displaced from their homeland as a result of the movement of the Chionites, superimposed by the invasions of the Kidarites from Eastern Turkestan, and later the Hephthalites from the Altai. The ethnonym of “Daha” completely disappeared from the sources of this time.

Analyzing the reasons for the Great Migration, L.N. Gumilev came to a well-grounded conclusion that the impetus was a century-long drought, which swept through the middle latitudes of the Eurasian continent in the 3rd century AD. At this time, all ancient states underwent a crisis. First, the Parthian State collapsed in the early 3rd century. In the 4th century AD, the Roman Empire, weakened by internal contradictions, became divided into two parts, with the subsequent degradation of its western part. The Kushan and Han states disappeared from India and China. However, it was especially hard for the steppe nomads: the absence of herbaceous vegetation led to a massive loss of livestock and widespread famine among the Huns, who dominated the entire steppe belt from Mongolia to the lower reaches of the Danube at that time. The entire population of the steppe zone was forced to migrate south to the areas of traditional agriculture.

Chinese, Indian, Sogdian, Iranian, and Roman written sources report the invasions of the Huns.

The drought forced the majority of the substrate of other steppe (including sedentary) cattle-breeding and agricultural peoples to migrate along with the Huns.

Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that the Huns or Chionites fought in the army of the Sassanids as their allies against the Romans. The Chionites had white complexions, showed high culture, and observed the law no worse than the Romans. All this distinguished them from the rest of the Huns. These Chionites might have been the descendants of the ancient population living in the middle reaches of the Syr Darya, which became involved in the general movement of migrants under the banner of the Huns. They might have been the carriers of the Kaunchi and Otrar-Karataus cultures— the descendants of the ancient Dahae. The burial rite of the deceased son of the Chionite leader, described by Marcellinus, was accompanied by lighting a fire, similarly to the Sarmatians and Dahae.

Archaeological evidence, primarily massive pottery complexes, reveals the influence of pottery traditions typical of the Kaunchi and Otrar-Karataus archaeological cultures of the middle Syr Darya on the pottery production of Sogd, Khorezm, Merv, and Bactria. After the 4th century AD, bell-shaped goblets disappeared from the typology of pottery in the oases in the basins of the Zarafshan and Kashkadarya; these became replaced by wide bowls with vertical rims, typical for the pottery of the 3rd–6th centuries AD. Spherical mugs with loop-shaped handles appeared in the Samarkand and Shakhrisabz oases. Their earlier prototypes again can be found among the pottery of the lower and middle Syr Darya. However, if in the former case, the handles of the mugs were made in the form of a lamb; on the products of Sogd, the animal head was turned into a small molded button on the upper part of the loop-shaped handle. Home production of rough molded kitchenware—cauldrons, pots, braziers, etc.— became widespread. The material culture of Nakhshab (Ancient Nakhshab) also manifests a strong influence of the Dzhetyasar culture from the lower reaches of the Syr Darya. During this period, most of the carriers of that culture settled in the lower reaches of the Kashkadarya and in the areas adjoining the borders of Khorezm.

Cessation of life in the ancient urbanized settlement of Shashtepa, located in the southwestern part of the presentday Tashkent along the ancient channel of the Salar, was associated with that time. In Minguryuk, life was also interrupted.

The migration of the Chionites along with the major part of the agricultural and cattle-breeding population of the Middle and Lower Syr Darya to the south resulted in the building of distinctive small and strongly fortified castles by the newcomers in the newly occupied territories—mainly in the peripheral zones of the oases. Migrants preserved not only the traditional features of their material culture, but also their ideological life, with rituals and religious paraphernalia; they built their temples in accordance with the sacred prototypes left behind in their homeland. These temples corresponded to the model of the temple in Minguryuk. The Setalak I temple on the western outskirts of the Bukhara oasis, which I excavated in the 1970s, is very close to it in time and structure. First, a temple structure square in plan view was built there; then it was mured up, and monolithic semi-oval towers were attached to it on four sides, following the model of the temple in Minguryuk (Suleimanov, Mukhamedzhanov, Urakov, 1983). Similar monolithic temple structures (the complexes of Chol-Tobe and Kzyl-Kainar-Tobe) were built in Semirechye near Taraz. The former complex contains two small rooms without entrances; the second complex has a narrow corridor-like room in which a warrior with weaponry of the Hunnic type was buried (Mershchiev, 1970). The Tepe-5 temple near the Kerkidon reservoir in the Fergana Valley (see Fig. 2) is an example of similar structure. It was built in the form of a monolith with a small closed room in the center (Gorbunova, 1972). In the course of subsequent rebuilding, four more similar towers were constructed between the four semicircular towers, which resulted in the eight-petaled rosette in plan view (see Fig. 2).

In recent years, a similar cruciform cultic structure has been excavated by E. Smagulov in the center of the town of Turkestan—Ancient Yassi. The structure is dated to the 3rd–4th centuries by a Huvishka’s coin, although the coin might have also gotten there later. The building was rebuilt and expanded several times. Back in 1936, photographs were published of the remains (discovered near Kabul) of a small monolithic tower structure, crossshaped in plan view, which belongs to the complex of the Sun temple—Khair Khaneh of the 5th–6th centuries. However, the cross in this case is of a different design—it is represented by four towers at the corners of the square (Hachkin, Carl, 1936: Pl. I). Importantly, the modern toponym “Khair Khaneh” is translated as the “House of Sacrifices” (see Fig. 2).

It should be mentioned that the Early Medieval archaeological complexes of Sogd, Fergana, and Semirechye preserved until the emergence of Islam their own techniques and typological features (especially in pottery), which had developed in the 4th–5th centuries.

Sculptural and pictorial images of female deities in urban temples of Nakhshab at the fortified settlement of Yerkurgan, Penjikent, Shahristan, and Dilberjin indicate that in the 4th–7th centuries these deities remained the main mediators between heaven and earth prior to Islam.

Relics of the Scytho-Sarmatian heritage in the culture of Old Rus

The Sarmatians migrated to the west from the Northern Caspian Sea region and Aral Sea region. Roman sources report their wars with the Dacians of Decebalus in the 2nd century BC. Trajan’s Column depicts the Dacian cavalry with the banner of a dragon-fish with an open mouth. S.P. Tolstov pointed out the similarity of the Dahae from the Aral Sea region and the Dacians of the Western Black Sea region (1948: 186). It is possible that after leaving their homeland in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya, some part of the Dahae together with the Sarmatians went far to the west and established their possessions on the borders with the Roman Empire.

The Sarmatians have been most often mentioned in the Greco-Roman sources. In the 2nd century BC, they were the true lords of the Northern Black Sea region, conquering the Scythian Kingdom on the Crimean Peninsula. According to B.A. Rybakov, the Proto-Slavs (Scythians – “plowmen” of Herodotus) had contacts with the Sarmatians at the turn of the Common Era in the Northern Black Sea region (1987: 219–220). It is known that ancient Slavs and Sarmatians together with Goths participated in the formation of the Chernyakhov culture of Eastern Europe. After the migration of the Huns to the west, the carriers of the Chernyakhov culture participated in the emergence of the Eastern Slavic group of tribes. The sanctuaries of the Chernyakhov culture also had a form of square grounds with idols; bonfires were made on them (Vinokur, 1972, 1983).

In the Late Sarmatian period (3rd–4th centuries AD), as a result of the advance of the Huns to the west, skeletons with circular deformation of the skull appeared in Sarmatian burials. Notably, Sarmatian cemeteries extended to the north into the interfluves of the Volga, Khoper, and Don Rivers. In the forest-steppe regions and in the upper reaches of the Volga and the Don, the Sarmatians mixed with the Veneti, and became a part of the emerging groups of Eastern Slavs (Berestnev, Medvedev, 2015). These observations are of fundamental importance for understanding the genesis of paganism in Old Rus.

It is known that after the Christianization of Rus in the 10th century, ancient temples and sanctuaries of the Slavs were destroyed. Information from the written sources about the destruction of temples of Perun in Kiev and Novgorod, as well as the idol on the Zbruch River, is confirmed by archaeological research (see Fig. 2). It has been established that all idols were thrown into the rivers. In Kiev and Novgorod, idols of Perun were made of wood. A four-faced stone statue carved of local limestone stood in the sanctuary of Zbruch (Rusanova, Timoshchuk, 1986).

For our topic, it is important to discuss the structure of such sanctuaries with the sculpture of an idol in the center. These were elevations round in plan view, with eight round depressions encircled by embankments along the perimeter. On the Zbruch and in Peryn near Novgorod, the structures looked like a symmetrical eight-petaled rosette in plan view. Similar in plan to the Early Medieval cultic structures of the Fergana Valley and comparable in sizes, all of them date back to the Early Middle Ages. However, in the Fergana Valley, such sanctuaries were monolithic adobe structures, while in the sanctuaries of the Zbruch and Peryn, the hill with the idol was surrounded by eight pits, where bonfires were kindled and animal sacrifices were made. This was a traditional ritual of sacrifice rooted in common IndoEuropean archaic times. Ash pits identical in content have been found at all of the above-mentioned cruciform structures in Middle Asia. Similarly to the monuments of Middle Asia mentioned above, remains of people buried in pits around the idol have been found in the sanctuaries of Old Rus. The authors of the excavations at the Slavic shrine on the Zbruch considered them to be human sacrifices (Ibid.). Christian authors of Old Rus accused the pagans of rituals of human sacrifice (Ibid.). Human burials also appear in the cruciform structures in Middle Asia mentioned above. For example, the bones of a male of middle age were laid in anatomical order in large ash pit under a clay mound near the entrance to the building of the 5th–6th centuries at Setalak in the Bukhara oasis. A small rectangular chamber, where a warrior with weaponry of the 5th–6th centuries AD was buried, was found in the continuous adobe masonry of the cruciform structure of Kzyl-Kainar-Tobe near the town of Taraz in Kazakhstan (see Fig. 2). Burials of human skulls with traces of fire were found in the interior spaces of the cruciform structures of Shashtepa in Tashkent and Shahr-i Qumis in Northeastern Iran. These skulls might have belonged to priests or revered people whose lives could have been associated with these sanctuaries. The oldest prototypes of the structures under discussion are represented in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya by the Scythian mausoleums of Northern Tagisken of the 10th–8th centuries BC and adobe mausoleums of the Chirik-Rabat culture of the 5th–3rd centuries BC. On the ground plans of all these structures, we may see the same composition—the combination of circle, square, and cross—the symbols of heaven, earth, and the sun (see Fig. 2). These commemorative cultic structures reflect the evolution of burial practices—transition from cremation in Northern Tagisken to inhumation in Chirik-Rabat with ritual burning of the mausoleum. Ritual burials at the sanctuaries of Old Rus may also constitute the burials of priests of ancient Slavic cults, and their funeral rite testifies to a transition from archaic IndoEuropean cremation to inhumation yet accompanied by the ancient rite of making a bonfire. It is known that traces of fire have been found in all Sarmatian burials. The reports of Christians may be a sheer slander against the pagans, like many ridiculous accusations by the early Muslims against the population of Sogd, which adhered to their old religion.

As far as the eight-partite structures of the outer peripheries in the two above mentioned sanctuaries of Old Rus and the Early Medieval structure in the Fergana Valley are concerned, these could have been the embodiment of the natural development of the idea on the symmetry of the cross. Transition from the four-petaled to eight-petaled ground plan is manifested in the cultic building in the Fergana Valley. The corners of the central square structure protruding between the four semicircular towers in this cruciform structure were transformed into semicircular towers, which resulted in a monolithic cultic tower or high platform, eight-petaled in plan view (see Fig. 2). This is certainly a conjecture. The evolution of ancient Slavic sanctuaries, initially represented by round and square elevated platforms on which idols stood and bonfires burned, might have followed the same trends. There were shrines and sanctuaries in the form of the cross in Old Rus. The central structure of the temple of Perun excavated by V.V. Khvoiko in Kiev, which had the form of an oval superimposed on the cross in plan view, was built of stone blocks in the 8th century. Semicircular pits were dug in the four cardinal directions at the sanctuary of the 10th century in Khodosovichi, which was cruciform in plan view. Bonfires were made in the pits, and bones and other waste from collective meals were thrown there in honor of the deity (Sedov, 1982: 286–287). The fact that the eight-petaled structures also had their own history is evidenced by the eighttower structure Garry-Kiariz I of the 7th–6th centuries BC in Turkmenistan (see Fig. 2). Its function raises questions (Pilipko, 1984). It is known that the eight-pointed star or eight-petaled flower was a symbol of the Great Aquatic Goddess—the goddess of love and childbirth. Her planet Venus (Aphrodite, Cholpan, Zuhra) appears for eight months as the evening star and for another eight months as the morning star, which has been known since prehistoric times.

All of these sanctuaries were usually built on river banks. Fragments of legends about the complex of river deities have survived. The main deities among them were the archaic river Nymph and her two companions, including the river dragon or sacred fish. The most famous narrative on this topic in Rus is the Novgorod tale about Sadko. The legends about Sadko written down from various storytellers do not coincide in details, but have their plot, storyline, and protagonists in common. In the earliest pre-Christian version of this epic tale, the events unfolded around three main characters—Sadko, the Virgin Whitefish, and the King of the Sea. In later versions, a Christian saint guiding Sadko’s behavior appeared in the plot. The female character is represented by two images—the mother Virgin Whitefish and her daughter Charnava, identified with the Chernava River which flows into the sacred Lake Ilmen. According to this most common version, Sadko was a lonely stranger, popular gusli player; he played music on his multistringed gusli entertaining the sea king. After he gained the support of the king, Sadko made a bet with the merchants of Novgorod that he could catch the Fish of the Golden Feather and become richer than them. The sea king did not disappoint Sadko, and after catching the fish, Sadko quickly became rich. The king of the sea demanded payment for this wealth. Sadko sank to the bottom of the sea and enchanted everyone with the music he played on the gusli . The king of the sea also started to dance, so that a hurricane raised on the sea and the waves sank all the ships. Only the appearance of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, who insisted on tear the strings of the gusli , before Sadko, saved everyone. Peace and tranquility at started to pervade the sea again. The contented sea king invited Sadko to become his relative. At the bride show, following the advice of the Virgin Whitefish, Sadko chose Charnava, the daughter of the king, out of hundreds of girls of the underwater kingdom. The newlyweds miraculously returned to Novgorod. According to another version of the epic tale, the newlyweds sailed away to the Khvalynskoye Sea (Caspian Sea) on ships donated by the sea king; this is an allusion to the fact that by origin Sadko was associated with the Sarmatian lands.

This Novgorod epic tale has preserved the oldest and, in fact, matriarchal mythologeme about the marriage of a guest to an autochthonous virgin. The same legend speaks about the origin of the Scythians from Hercules, who married the serpentine maiden, the daughter of the Borysthenes River. According to the Shahnameh, Rustam (the hero of the Sako-Sogdian epics) married Takhmina, but he himself was the grandson of the dragon Zahhak (Dahak) on the side of his mother, a pagan who did not know the doctrines of Zarathushtra.

The advance of the late Sarmatians to the north could have accelerated after their defeat by the Huns in 375 in the steppes of the Northern Black Sea region. Part of the Sarmatians (the Ases) entered the Hunnic union, while the irreconcilable part left to the north.

As mentioned above, in the second century BC the Dahae occupied not only the entire Amu Darya basin, but also the lands in the middle reaches of the Indus and Afghanistan, after crossing the Hindu Kush. There, in Gandhara, the archaic hymns of Mithra (Avestian “Mihr” – ‘deity of the treaty’, Russian “Mir”), Aredvi Sura Anahita, and Hvarn have been preserved; later, they entered the canon of Zoroastrianism, even though they contradicted the doctrine of Zarathushtra reflected in his sermons-gathas (Lelekov, 1992: 247–255). This, the so-called, Drangiana tradition of the Avesta is associated with the tradition of the Helmand River valley—repeating the hydronym of the sacred Lake Ilmen. “Helmand” means ‘depositing clay, silt’. The water in the river and lake into which it flowed was muddy, like in Lake Ilmen and in the Volkhov River flowing from it.

In his book The Paganism of Old Rus , Rybakov made an exhaustive analysis of the cultic and mythological semantics of idols on the Zbruch and in the sanctuary of Perun on Lake Ilmen and in Novgorod (1987). He emphasized that the idol on the Zbruch was set at a sanctuary which appeared in distant Scytho-Sarmatian times, and from there it was thrown into the river in the

10th century. Rybakov identified that stone idol from the sanctuary with the most ancient deity of the Slavs— Rod-Svyatovid, the same as Svarog or Stribog (Ibid.: 172–173). In Novgorod, the idol of Perun—the patron deity of the Prince and his retinue, the god of thunder and lightning of the Slavic pantheon—was set up by Dobrynya Nikitich in 980, and stood for only eight years until Prince Vladimir decided to convert to Christianity. All these eight years, the unquenchable fire burned near Perun similarly to the cultic temples of the Parthian rulers—descendants of the Dahae and Sarmatians. Avestan Farn or Sogdian Parn was also associated with celestial fire. During forced Christianization, the people (Slovenes) led by their pagan priest Bogomil-Solovei rebelled against Dobrynya Nikitich. The image of Solovei (the oldest water deity) is associated with the snake or lizard of ancient Russian mythology. The source reports that the slogan “It is better to die than to give our gods over to mockery” raised five thousand residents of Novgorod to protest; but Dobrynya defeated the pagans, and in 988 threw the idol of Perun into the Volkhov River.

Rybakov cited a legend about the emergence of the Slovenes, written down in the 17th century on Lake Ilmen: “Two tribal leaders left their old lands in ‘Scythenopontos’ and began to search for ‘favorable places’ ‘in the world’; ‘like sharp-winged eagles they flew over the desert’; after forty years of wandering, they reached the Great Lake named after Sloven’s sister Ilmera. On the bank of the Volkhov River (‘then called’ “muddy”’), the town of Slovensk the Great (‘and now Novgrad’) was built. And after that time, the Scythian newcomers began to be called Slovenes…” (Ibid.: 179). We should mention that the muddy Karasu River—‘Black Water’, the Sogdian name Matrud—‘muddy, dim river’—also flows near Samarkand and is also considered sacred.

According to Rybakov, earlier, before the idol of Perun was set there, a sanctuary of the ancient deity of the Volkhov River had been in that place (Slavic Veles + ov, ob – Iranian ‘water’. Cf. the name of the most ancient Aryan town of Balkh on the Balkhob River)—a water lizard that the Christian chronicler called “Korkodel” (Ibid.: 180–190). Rybakov cited an Old Russian text that Ov (“someone”) conducted magical rituals of worshiping the goddess of the river and god-beast living in it. Ov made a sacrifice for a rich catch (Ibid.: 180). This archaic text preceded the legend of Sadko. This classical triad reappears in the hymn of the Avesta about the goddess of the river Aredvi Sura Anahita with the dragon Gandharva living in her waters, and a protagonist who worships this river.

Rybakov pointed out that the ancient gusli discovered during the excavations of the 12th century Novgorod in the form of a wooden trough with strings, had a handle with representation of the head of a dragon or lizard—the king of the sea. This is the Slavic water deity Jassa—Yasha, Lizard. As Rybakov observed, in the southern Kiev triad of Yashcher (Lizard), Lada, and her daughter Leya, Lizard corresponded to old Slavic “Rod” (clan). According to V.V. Sedov, the Slovenes were genetically related to the Lechid tribe of Poland (1982). There is another version: the Slovenes came from the banks of the Danube. Fibulae were decorated with lizard heads among the Slavs of the Dnepr region of the 6th–7th centuries AD. Later, the dragon image often appeared in the decoration of the Christian architecture of Novgorod in the 10th–13th centuries. Rybakov came to the conclusion that the history of the sanctuary in Peryn could be divided into three stages: the first stage was associated with the pagan cult, lake, river, and fish (led by Yashcher), the second stage with the artificial introduction of the cult of Perun, and the third stage with forced Christianization (1987).

The Sarmatian sanctuaries of the first century AD were square or round areas in the open air, on which large bonfires were lit. The sanctuaries of the carriers of the Chernyakhov culture and ancient Slavic places of worship, where the stone idol stood, were the same (Vinokur, 1972, 1983).

According to Sedov, two more round platforms, which could have been dedicated to two female deities of the Slavic triad, stood (one on either side) by the sanctuary of Perun in the place where the idol of the Yashcher (the deity of the Volkhov River) had previously been (1982).

It is important for our research topic that a pair of sacrificial knives was discovered in the famous Chernaya Mogila burial mound, where one of the pre-Christian Kiev princes of the 10th century was buried according to the cremation rite (Rybakov, 1987: 216). The earliest pairs of bronze sacrificial knives have been found in the Scythian burial mounds in the Northern Black Sea region. Apparently, bronze knives quickly became blunt during sacrifices of large animals among the Scythians, and therefore it was the custom to prepare two knives for ritual celebrations. Even today, when cutting carcasses, butchers usually use not one knife, but several, and often sharpen them. Paired knives have been also found in the inventory of a royal person of the first century BC, buried in Tillya-Tepe (Fig. 5). Two identical knives were inserted into a golden scabbard (Sarianidi, 1985: Ill. 162; 1989: 98–101). The information about this find given by V.I. Sarianidi in his 1985 book was somewhat incorrect. At the invitation of Sarianidi, I participated in the expedition, and excavated and unearthed this royal burial, and I know that two identical narrow knives were inserted into the same scabbard. A similar scabbard with paired ritual knives was also present on the belt of one of the khalats of the Emir of Bukhara, which was exhibited in the museum collection of the Ark of Bukhara in the 1960s. The Emir’s purple velvet robe was embroidered with silver thread; a

Fig. 5 . A pair of kosh pichak knives. 1st century BC. Tillya-Tepe (Sarianidi, 1985).

5 cm

Mies kazanlar kainadi, apa kel, apa kel . – Copper cauldrons have boiled up, come, sister, come, sister.

Kosh pichaklar kairaldi, apa kel, apa kel . – The kosh pichak knives have been sharpened, come, sister, come, sister…

At that very moment, the sister breaks in with a mug in her hand; she rushes to the kid, and pours water from the sacred spring into his mouth. A miracle happens, and the kid turns back into her brother. The Kalmyks, struck by the miracle, let them go unharmed.

The Russian fairy tale about Sister Alyonushka and Brother Ivanushka has a similar plot. Such coinciding plots belonging to peoples who seem to be remote in space and time, are called “wandering” by folklorists. Archaeology, to the best of its capacity, makes it possible to trace the paths and times of migrations of these subjects, associated with specific types of material culture of particular ethnic groups in place and time.

silver scabbard, from which the turquoise handles of two identical knives protruded, was attached to his wide silver belt. The memory of a pair of sacrificial knives “kosh pichak” has survived until this day in Uzbek folklore: the characters of fairy tales sharpen “kosh pichak” before sacrificing an animal.

In this regard, the following plot of the Uzbek fairy tale can be summarized. An older sister and her brother go into the field to gather “mother-kaymak” (dandelions). When they return to the house, ashes await them: the Kalmyks have ravaged and burned the village. The children go to search for at least anyone who has survived. The sun is scorching mercilessly. The brother asks for a drink; the sister persuades him to be patient. There is no water anywhere, and suddenly, the brother sees a hoofprint filled with water on the ground, and drinks from it. It is goat-urine, and the boy turns into a kid. After the sister realizes what has happened, she leaves her brother there and runs to the sacred spring for miracle-working water. At this time, the Kalmyks have set up a camp nearby, and a son has been born to their leader. The leader has ordered the organization of a “beshik-toi” (a feast in honor of the swaddling of a newborn in a cradle) for the people. Those who were sent on a hunt to bring meat for the feast find the kid. Preparations for the feast at the Kalmyk camp are already in full swing. The brother bleats loudly and calls his sister:

Altyn beshik boulandi, apa kel, apa kel . – They have tied the golden cradle, come, sister, come, sister.

Conclusions

Cyrus’ historical campaign against the nomads was caused by the need to secure the northeastern borders of the Kingdom of Kingdoms he was building, in which he was Shahan Shah—the King of Kings—before his distant campaign to Egypt. Cyrus knew the Scythians who found themselves within the boundaries of his rapidly expanding Empire, yet he underestimated the powerful mobilization capacity of the nomadic tribes of the Great Steppe, which at that time were also creating extensive military and political entities. Cyrus became a victim of his own mistake. After he was defeated by the united coalition of the nomads from Middle Asia, two early state formations of the Dahae and Massagetae emerged. Their oases appeared in vast delta of the Syr Darya. The example was the southern neighbor—the Ancient Khorezm, which appeared in the Amu Darya delta a hundred years earlier, in the Median time. Khorezm could certainly not avoid fighting with Cyrus together with the nomads, although there is no information about this in the sources.

The Dahae settled in the southwestern part of the delta of the Syr Darya and formed their semi-sedentary early urban culture. Two hundred years after the disastrous draining of the delta channels in their oasis, they migrated mainly to the south and east, and created their own larger and smaller states there. It is no coincidence that precisely at this time, the carriers of the Prokhorovka culture, who continued to roam in the Southern Urals, migrated to the west and invaded the lands of the Sauromates, as a result of which the ethnic name “Sarmatian” appeared. A part of the Dahae might have left for the steppes of Kazakhstan, where they mixed with the Massagetae and Saka people, who remained in the steppe in the second century BC, originating the strong state of Kangju, mentioned in the Chinese sources.

The Sarmatians constituted the western wing of this large ethnic and cultural community of the early nomads, which may have been a confederation, and migrated west starting in the 3rd century BC. They moved on the paths by which the Scythians had passed five hundred years before. Like the Dahae in Middle Asia, the Sarmatians dominated the steppes in the south of the present-day Russia until the appearance of Huns in the 3rd century.

In the 3rd–4th centuries AD, owing to the subsequent aridization of climate and advance of the Huns to Middle Asia, the carriers of the Kaunchi and Otrar-Karatau cultures (the late derivatives of the Dahae culture) migrated to the south. The influence of the pottery traditions of the Kaunchi artisans has also been observed in the Syr Darya basin. At this time, cultic and commemorative structures cross-shaped in plan view, with ritual premises inside, became replaced by squat monolithic towers or platforms cross-shaped in plan view; but, unlike the earlier structures, the ends of the crosses in them were not rectangular, but rounded in the form of semicircular towers. These were monolithic structures, on top of which fire could have been made and sacrifices performed. In plan view, these buildings have the form of four-petaled rosette. A thick layer of ash with the remains of ritual sacrifices and meals has survived around them. In the Early Middle Ages, four more of the same towers were built in the spaces between the four towers in a similar structure in the Fergana Valley. Thus, the ground plan of the structure acquired the form of an eight-petaled rosette similarly to the pre-Christian sanctuary on the Zbruch and sanctuary Peryn on the sacred Lake Ilmen. It is possible that idols whose cult was mentioned by the Arabs stood there as in the pagan sanctuaries of Rus, and fires burned.

These ancient traditions of spiritual culture from the middle latitudes of Eurasia in the Middle Ages were swept away by the monotheistic religions (Islam and Christianity) that came from the Eastern Mediterranean and were more in line with the needs of medieval societies.

Список литературы Traces of the Dahaean and Sarmatian cultural legacy in Ancient Turan and Old Rus

- Balakhvantsev A.S. 2016 Sredneaziatskiye dakhi v IV-II vv. do n.e. Rossiyskaya arkheologiya, No. 1: 11-24.

- Berestnev R.S., Medvedev A.P. 2015 Sarmatskiye pamyatniki v lesostepnom mezhdurechye Dona i Volgi (opyt rayonirovaniya). Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser 4. Istoriya. Regionovedeniye. Mezhdunarodniye otnosheniya, vol. 20 (2): 7-17.

- Dandamaev M.A. 1991 Review of Acta Iranica. Encyclopedie permanente des Etudes iraniennes. Deuxième série, XVII (28). A Green Leaf. Papers in Honour of Professor Jes P. Asmussen. Leiden: E.G. Brill, 1988. Vestnik drevnei istorii, No. 3: 209-215.

- Filanovich M.I. 1983 Tashkent. Zarozhdeniye i razvitiye goroda i gorodskoy kultury. Tashkent: FAN.

- Filanovich M.I. 2010 Drevnyaya i srednevekovaya istoriya Tashkenta v arkheologicheskikh istochnikakh. Tashkent: FAN.

- Gorbunova N.G. 1972 V Drevney Fergane. Tashkent: FAN.

- Gorbunova N.G. 1985 Pamyatniki Kerkidonskoy gruppy v Yuzhnoy Fergane. ASGE, iss. 26: 45-70.

- Gorbunova N.G. 1994 Poseleniye Ark-tepe v Yuzhnoy Fergane. Rossiyskaya arkheologiya, iss. 4: 191-206.

- Hachkin J., Carl J. 1936 Recherches Archéologiques au Col de Khair khaneh près de Kabul. In Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique Franşaise en Afghanistan, vol. VII. Paris: Les Éditions dʼArt et dʼHistoire, pp. 14-17.

- Itina M.A., Yablonsky L.T. 2001 Mavzolei Severnogo Tagiskena. Pozdniy bronzoviy vek nizhney Syrdaryi. Moscow: Vost. lit.

- Ivanov V.V., Toporov V.N. 1982 Slavyanskaya mifologiya. In Mify narodov mira, vol. 2. Moscow: Sov. entsikl., pp. 450-456.

- Lelekov L.A. 1992 Avesta v sovremennoy nauke. Moscow: (s.n.).

- Mershchiev M.S. 1970 Poseleniye Kzyl-Kainar-tyube I-IV vv. i zakhoroneniye na nem voina IV-V vv. In Po sledam drevnikh kultur Kazakhstana. Alma-Ata: Nauka KazSSR, pp. 79-93.

- Nyberg N.S. 1938 Die Religionen des alten Iran, Bd. 43. Leipzig: MVAG, pp. 190-323.

- Pilipko V.N. 1984 Poseleniye rannezheleznogo veka Garry-Kyariz I. In Turkmenistan v epokhu rannezheleznogo veka. Ashgabat: Ylym, pp. 28-58.

- Podushkin A.N. 2015 Sarmatskaya atributika v arkheologicheskikh kompleksakh katakombnykh pogrebeniy arysskoi kultury Yuzhnogo Kazakhstana (I v. do n.e. - III v. n.e.). Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser. 4. Istoriya. Regionovedeniye. Mezhdunarodniye otnosheniya, vol. 20 (5): 67-77.

- Rusanova I.P., Timoshchuk B.A. 1986 Zbruchskoye svyatilishche. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, No. 4: 90-100.

- Rybakov B.A. 1987 Yazychestvo Drevney Rusi. Moscow: Nauka.

- Sarianidi V.I. 1985 Bactrian Gold: From the Excavations of the Tillya-Tepe Necropolis in Northern Afghanistan. Leningrad: Aurora Art Publ.

- Sarianidi V.I. 1989 Khram i nekropol Tillya-tepe. Moscow: Nauka.

- Sedov V.V. 1982 Vostochniye slavyane v VI-XIII vv. Moscow: Nauka. (Arkheologiya SSSR).

- Smagulov E.A., Erzhigitova A.A. 2013 Tsitadel drevnego Turkestana: Nekotoriye itogi arkheologicheskogo izucheniya, 2011-2012 gg. Izvestiya AN Respubliki Kazakhstan, No. 3: 82-99.

- Smirnov K.F., Petrenko V.G. 1963 Savromaty Povolzhya i Yuzhnogo Priuralya. Moscow: Nauka. (SAI; iss. D. 1-9).

- Snesarev G.P. 1969 Relikty domusulmanskikh verovaniy i obryadov uzbekov Khorezma. Moscow: Nauka.

- Suleimanov R.H. 2000 Drevniy Nakhshab. Problemy tsivilizatsii Uzbekistana. VII v. do n.e. - VIII v. n.e. Samarkand, Tashkent: FAN.

- Suleimanov R.H., Mukhamedzhanov A.R., Urakov B. 1983 Kultura Drevnebukharskogo oazisa. III-VI vv. n.e. Tashkent: FAN.

- Tolstov S.P. 1948 Drevniy Khorezm. Moscow: Izd. Mosk. Gos. Univ.

- Trever K.V. 1940 Pamyatniki greko-baktriyskogo iskusstva. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR.

- Vinokur I.S. 1972 Istoriya i kultura chernyakhovskikh plemen DnestroDneprovskogo mezhdurechiya. II-V vv. n.e. Kiev: Naukova dumka.

- Vinokur I.S. 1983 Chernyakhovskiye plemena. In Slavyane na Dnestre i Dunaye. Kiev: Nauk. dumka, pp. 105-135.

- Weinberg B.I. 1999 Etnogeografiya Turana v drevnosti. VII v. do n.e. - VIII v. n.e. Moscow: Vost. lit. RAN.

- Weinberg B.I., Levina L.M. 1993 Chirikrabatskaya kultura. Nizovya Syrdaryi v drevnosti, iss. 1. Moscow: Nauka.

- Yagodin V.N. 1982 Arkheologicheskoye izucheniye kurgannykh mogilnikov Kaskazhol i Berniyaz na Ustyurte. In Arkheologiya Priaralya, iss. I. Tashkent: FAN, pp. 39-81.

- Zadneprovsky Y.A. 1985 Gorodishche Bilovur-tepe (Vostochnaya Fergana). KSIA, iss. 184: 88-95.