Trends and Prospects of Labor Migration from Central Asian Countries to the United Kingdom

Автор: Ryazantsev S.V., Kurylev K.P., Rakhmonov A.Kh., Rakhimov K.Kh., Chupin A.L.

Журнал: Вестник ВолГУ. Серия: История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения @hfrir-jvolsu

Рубрика: Современные международные процессы

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.30, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Introduction. Among European countries, the UK is experiencing one of the most acute labor shortages, especially in labor-intensive and low-prestige sectors such as agriculture. Following Brexit, the UK was compelled to expand the geography of labor recruitment beyond the traditional pool of Eastern European seasonal workers (Poland, the Baltics, Bulgaria, and Ukraine) to include Central Asian countries. This article aims to identify the trends and prospects of labor emigration from Central Asian countries to the UK within the context of growing political and economic competition among key actors in the region. Methods and materials. The study combines analytical, statistical, and sociological approaches. It draws on World Bank and IOM datasets on labor migration and remittances, complemented by thematic content analysis of Russian and British media and expert interviews. Official documents from government agencies, embassies, recruitment agencies, and migrant training centers are also examined. Analysis. The analysis covers the scale, drivers, and channels of emigration from Central Asia to the UK, the participation of Central Asian workers in the British labor market, and the prospects for seasonal migration. Results. The results show that labor shortages in the UK labor market are the primary driver of migration from Central Asia. The reorientation of migration flows from the Russian direction is explained by the economic downturn in Russia, the tightening of migration legislation and the spread of English among young people in Central Asian countries. Since 2021, there has been an increase in seasonal migration of low-skilled workers, primarily through public and private recruitment agencies. Authors’ contribution. S.V. Ryazantsev – research concept and economic analysis of labor migration; K.P. Kurylev – political aspects and international relations; A.Kh. Rakhmonov – social consequences and interview analysis; K.Kh. Rakhimov – historical context and geopolitical factors of migration; A.L. Chupin – statistical analysis and policy recommendations on migration.

Labor migration, seasonal migration, Central Asian countries, UK, recruitment agencies, migration service, working conditions, adaptation, Tajik migrants

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149149150

IDR: 149149150 | УДК: 314.7 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu4.2025.4.18

Текст научной статьи Trends and Prospects of Labor Migration from Central Asian Countries to the United Kingdom

DOI:

Цитирование. Рязанцев С. В., Курылев К. П., Рахмонов А. Х., Рахимов К. Х., Чупин А. Л. Тенденции и перспективы развития трудовой миграции из стран Центральной Азии в Великобританию // Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 4, История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения. – 2025. – Т. 30, № 4. – С. 210–222. – (На англ. яз.). – DOI:

Introduction. Labor migration has become a key source of household income in the Central Asian countries and an important driver of their economic development. The present study focuses on Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan; Turkmenistan is excluded because of its closed nature and the lack of reliable statistics on migratory flows. According to World Bank estimates [6], remittances account for 35– 45 percent of Tajikistan’s GDP and about 30 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP. Between 500 000 and 600 000 Tajik nationals – roughly 20– 25 percent of the economically active population – are working abroad [4], while Kyrgyz migrants numbered 858 000 in the 2022 census. Since the early 2000s, Russia and, later, Kazakhstan have been the principal destinations [17], but economic and geopolitical shocks have encouraged a diversification of flows [12].

Interest in the United Kingdom has grown rapidly since 2021 [5]. Initially, the migrants were mainly students and skilled professionals, but a noticeable influx of seasonal agricultural workers has now emerged. With support from the International Organization for Migration and the UK Seasonal Workers Scheme, an infrastructure for organized recruitment is taking shape in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. British firms such as Pro-Force work with migration authorities and local agencies to place personnel in farms and in companies specializing in the harvesting of vegetables and berries [28]. In this way an institutionalized mechanism of transnational hiring is being formed that provides legal employment channels and reduces the risk of labor and social violations for both migrants and the host side.

Theoretical approaches. Contemporary migration scholarship rests on a multi-level analytical framework in which macro-, meso-, and micro-dimensions form an interdependent system of factors that shape both the direction and the intensity of migratory flows. At the macro level, decisive forces include global and structural determinants: economic disparities between donor and recipient countries, demographic growth in the Central Asian (CA) states, changing labor-market conditions, and the evolution of migration policies in destination countries. The British labor market, suffering a shortage of low- and medium-skilled workers after Brexit, coincides with the economic slowdown in Russia and Kazakhstan – traditional destinations for CA labor migrants – thereby strengthening the “push” and “pull” incentives that favor reorientation towards the United Kingdom. Relevant macro factors also encompass international agreements, such as the 2021 Tajikistan – UK treaty on seasonal workers, and the reform of the British visa system, which obliges applicants to earn seventy points across criteria of education, salary, language proficiency, and a job offer from a licensed sponsor.

The meso level is defined by institutions and networks linking prospective migrants to employers. Recruitment agencies (Agri-HR, Osrodek-HR, and others), diaspora associations, migrant-training centers in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, and the migration services of CA countries all function as mediators that reduce the informational and transaction costs of mobility. By providing access to vacancies, facilitating the issue of documents, and consolidating emergent migration routes, these actors help embed new patterns of emigration.

At the micro level, individual motivations remain paramount: the pursuit of higher earnings, the desire for socio-economic advancement and career development, and the possession of linguistic capital or social ties in the destination country. An IOM online survey (2019) confirmed that economic expectations and clear career prospects are the chief determinants of choice for young Central Asians, while risks and benefits are additionally weighed against marital status and accumulated savings.

A political-economy perspective views these levels through the prism of competing material interests. The depreciation of sterling and the decline in UK earnings – highlighted by J. Portes – interact with the tightening of the visa regime noted by D. Syme, M. Moskal, and N. Tyrrell, together producing fluctuating labor-market attractiveness. Meanwhile, rival destinations (the USA, the EU, China, Turkey, Iran, and Russia) have intensified their competition for CA labor resources, adding complexity to the migration landscape [8].

Russian research underscores the growing significance of these factors. S.V. Ryazantsev points to the proactive strategies of receiving states in attracting CA migrants set against a backdrop of stricter Russian migration policy and heightened competition from other EAEU citizens. A.Kh. Rakhmonov links Tajik workers’ pivot towards Europe to the post-2014–2015 currency crisis decline in real dollar incomes [33]. Subsequent shocks – the 2022 mobilization campaign, sanctions, and the withdrawal of foreign companies – have only reinforced this tendency.

In sum, today’s flow of labor migrants from Central Asia to the United Kingdom results from a synergy of macroeconomic imbalances and regulatory reforms, meso-level brokerage infrastructures, and the migrants’ own micro-level pragmatic aspirations. Understanding this layered architecture allows for a more accurate assessment of future diversification in migration routes and the formulation of well-grounded policy responses.

Sources of information and research methods. This study employs analytical, statistical, and sociological methods. Statistical data on labor migration from Central Asian countries for the period 2000–2024 vary in quality due to the specific characteristics of national migration accounting systems. The most comprehensive and systematic data are provided by Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan through current administrative records, population censuses, and labor force surveys. Data from Tajikistan are less detailed and are primarily based on administrative statistics from the Migration Service. Uzbekistan has only recently begun to publish information on international labor migration.

Statistics on the number of labor migrants and the volume of remittances are obtained from the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Agency on Statistics under the President of the Republic of Tajikistan, and the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, as well as from international sources such as the World Bank and the International Organization for Migration. In addition, data on the number of seasonal migrants and the structure of labor migration from Central Asia were published in 2024 by the UK Office for National Statistics.

A qualitative analysis was also conducted based on media publications and expert interviews with representatives of the IOM, academics, and officials from relevant government bodies. The collected material was systematized and compared, allowing the identification of both quantitative trends and qualitative mechanisms shaping migration from Central Asia to the United Kingdom.

Discussion. The United Kingdom is experiencing an acute labor shortage in the laborintensive yet lower-status sectors of its economy – agriculture, transport, construction, services, and municipal utilities [31]. This deficit was sharply worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic: in January 2022 the country lacked roughly half a million workers [39]. According to the UK Office for National Statistics, the number of vacancies climbed to a new peak of 1.3 million between March and May 2022 – half a million more than before the pandemic [27]. In the first quarter of 2022, for the first time since records began, nationwide vacancies outnumbered the unemployed. The shortage reflects the combined impact of the pandemic and Brexit [30]. Agriculture has been the hardest-hit sector, traditionally dependent on seasonal workers from the EU during planting and harvest periods [32]. The share of temporary (seasonal) workers in 2022 rose to 150 percent of the 2021 level (Table 1), underscoring severe staffing gaps. EU workers are no longer arriving because they cannot satisfy the UK’s post-Brexit visa requirements: wages in the sector are low, while the salary threshold for a work visa is high [23].

A further driver of migration from Central Asia to the United Kingdom is the comparatively high remuneration now offered in the British agricultural sector.

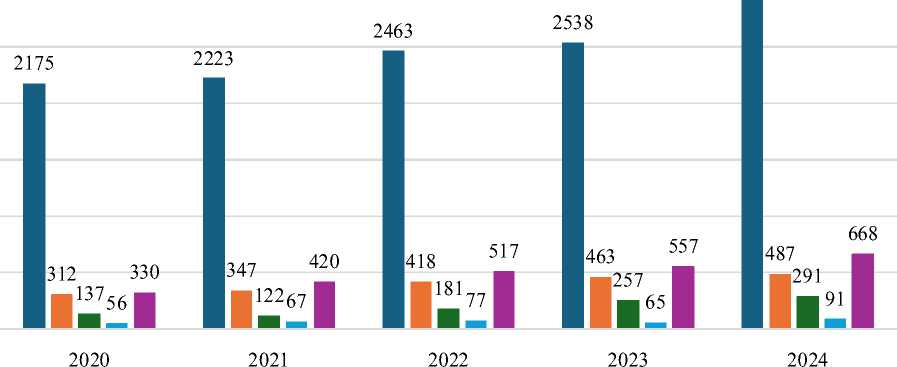

The minimum hourly wage in UK agriculture stood at Ј9.50 in 2022 [11], rose to Ј10.40 in 2023 [11], and reached Ј11.50 in 2024 [19]. Between 2020 and 2024, the average monthly pay for an agricultural worker in the United Kingdom was about USD 2,462. In the Central Asian countries, by contrast, agriculture has long been the lowest-paid sector [3]. The sharpest gap is observed in Tajikistan, where the average agricultural wage amounted to just USD 71 per month over 2020– 2024 (Fig. 1). This stark differential has clearly acted as a strong push factor for Tajik workers with farming experience [13].

UK Office for National Statistics data show that by March 2022 some 277 thousand work visas had been issued to foreign nationals – 2.5 times the 2021 total. Roughly 66 percent of the visas granted in 2022 went to skilled workers (Table 1).

■ UK ■ Kazakhstan ■ Kyrgyzstan ■ Tajikistan ■ Uzbekistan

Fig. 1. Average monthly agricultural wages in Central Asia and the United Kingdom, 2020–2024, USD Note. Compiled by the authors from data in sources: [1; 2; 10; 14; 15].

Table 1. Number of work visas issued to foreign nationals to enter the UK, January – March 2020–2022

|

Worker category |

Jan. – Mar. 2020 (thousand visas) |

Jan. – Mar. 2021 (thousand visas) |

Jan. – Mar. 2022 (thousand visas) |

Visa-issuance growth index in 2022 vs 2020 (%) |

Visa-issuance growth index in 2022 vs 2021 (%) |

|

Skilled employees |

110.0 |

76.1 |

182.2 |

66 |

139 |

|

Seasonal workers |

40.3 |

24.2 |

60.3 |

50 |

150 |

|

Other types of workers |

29.1 |

17.1 |

28.2 |

3 |

65 |

|

Highly-skilled specialists |

5.3 |

3.7 |

6.5 |

23 |

76 |

|

Total |

185.0 |

112.0 |

277.1 |

50 |

129 |

Note. Compiled by the authors from data in source: [26].

The combination of these factors has widened the “windows of opportunity” for drawing labor from new supplier countries – including the Central Asian states – and has greatly enhanced the diversification of seasonal-migration sources [24]. Prior to Brexit, the influx of such workers was governed by the EU-wide 2014 Seasonal Workers Directive, which set common standards for short-term employment in agriculture and tourism while protecting foreign employees from exploitation [30; 37]. After leaving the EU, the United Kingdom retained the directive’s core provisions: a seasonal-worker visa limits the stay to five to nine months per year, with scope to extend the contract or change employer as long as visa conditions are strictly observed [20]. It is important to note that the EU directive itself is not a law but a framework that must be transposed into national legislation; this enabled London to adapt its key norms to domestic needs. A further incentive is financial: since October 2022, the minimum hourly rate in agriculture has been raised to Ј10.10, effectively bringing the pay of low-skilled seasonal workers close to that of skilled specialists [16].

Seasonal migrants from Central Asia enjoy the same rights as local workers with respect to recruitment, wages, working hours, leave, health and safety, and access to core social security benefits (public housing excepted) [22]. These guarantees – combined with persistent staffing shortages – make the UK labor market an attractive alternative destination for migrants from the region.

Analysis. Labor migration from the Central Asian states to the United Kingdom was initially negligible and consisted almost exclusively of highly qualified specialists and students [21]. After the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union, however, a sharp labor shortage emerged in agriculture as the traditional inflow of seasonal workers from Eastern Europe dwindled. In response, the British Government launched the temporary Seasonal Workers Scheme in 2019, aimed at recruiting employees from outside the EU – including migrants from Central Asia and, in particular, Tajikistan. Under the scheme, up to 38,000 visas were allocated to the agricultural sector and another 2,000 to poultry enterprises; by the end of 2022, a total of 34,532 seasonal visas had been issued [38].

The program – extended through 2024 [9] – has become indispensable to British farms and agrobusinesses, which depend on migrant labor for harvesting fruit and vegetables and for other farm tasks [25]. Organized temporary migration took shape in 2021, when the British company Pro-Force began inviting citizens of the Central Asian republics for seasonal work. In Tajikistan, deployment to the United Kingdom is arranged with the assistance of the Migration Service, the Ministry of Labor, Migration and Employment, and the Embassy of Tajikistan in London.

In 2022 migrants from Central Asia received a striking share of the United Kingdom’s seasonal visas: 4.3 thousand (12.6 percent) went to Kyrgyz nationals, 4.23 thousand (12.3 percent) to Uzbeks, 3.91 thousand (11.3 percent) to Tajiks, and 2.67 thousand (7.8 percent) to Kazakhs – together amounting to roughly 15.1 thousand visas, or about 40 percent of the total (Table 2). For comparison, the single largest national group was Ukrainians (7.3 thousand; 21.3 percent), while the leading African and South Asian sources were Nepal (2.7 thousand; 8.0 percent) and Indonesia (1.45 thousand; 4.2 percent). Central Asia is therefore rapidly becoming a key supplier of seasonal labor to the UK agricultural sector.

The growth rates confirm this trend: whereas in 2021 the UK Department for Work and Pensions issued only about 2.4 thousand permits to citizens of all four Central Asian countries combined, by the end of 2022 the figure had climbed to roughly 15.5 thousand. Quotas for 2023 and 2024 have been maintained at not less than 45 thousand visas per year (covering agriculture and poultry), signaling the consolidation of the region’s new migratory role. The expanding recruitment of Central Asian workers is directly linked to the post-Brexit shift in British migration policy: the end of free movement for EU citizens forced employers to look more actively beyond Europe, and the Central Asian labor markets have become an attractive alternative.

As Table 2 shows, migration flows to the United Kingdom from the Central Asian republics are still modest relative to those from traditional donor regions – South Asia and Eastern Europe – but they are growing steadily. India and Pakistan continue to account for the largest diasporas and to top the migration rankings, so the combined share of Central Asian nationals in overall UK immigration remains small. Even so, the region already plays a noticeable role in the seasonal agricultural workforce: in 2022 Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan together supplied more than 40 percent of all workers admitted under the scheme.

Table 2. Distribution of UK Seasonal Worker visas (HORT – agriculture) by country, 2022

|

Country |

Visas issued (thousand) |

Share of total (%) |

|

Ukraine |

7,3 |

21,3 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

4,3 |

12,6 |

|

Uzbekistan |

4,2 |

12,3 |

|

Tajikistan |

3,9 |

11,3 |

|

Nepal |

2,7 |

8,0 |

|

Kazakhstan |

2,6 |

7,8 |

|

Moldova |

2,1 |

6,4 |

|

Indonesia |

1,4 |

4,2 |

|

Romania |

1,1 |

3,3 |

|

Bulgaria |

1,1 |

3,0 |

Note. Compiled by the authors from data in source: [26].

Overall, the structure of the UK labor market is still shaped by large communities from India, Poland, Pakistan, Romania, and Ireland, which together represent roughly one-third of the migrant contingent (about 16 percent of the total population). South Asia (India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) and Eastern Europe (Poland and Romania) have long provided both skilled and unskilled labor, while African countries – especially Nigeria and Ghana – are strongly represented in the service and health-care sectors. Yet between 2021 and the first quarter of 2024, the United Kingdom recruited about 50 thousand seasonal workers from Central Asia (Table 3), underlining the rapid expansion of labor flows and the growing importance of the region to the British economy.

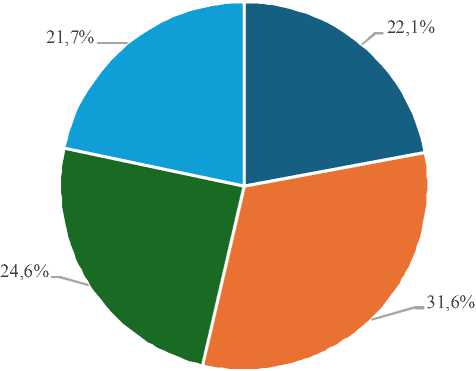

Between 2021 and the first quarter of 2024, the largest shares of Central Asian seasonal migrants came from Kyrgyzstan (31.6 percent)

and Tajikistan (about 25 percent). Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan contributed 22.1 percent and 21.7 percent, respectively (Fig. 2). These figures show that labor migrants from Central Asia are now entering the UK labor market in appreciable numbers.

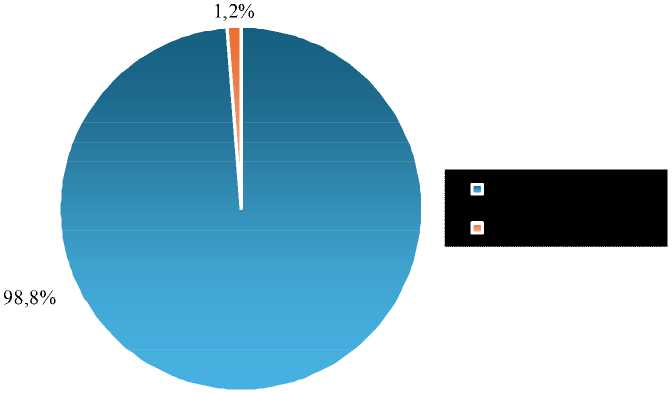

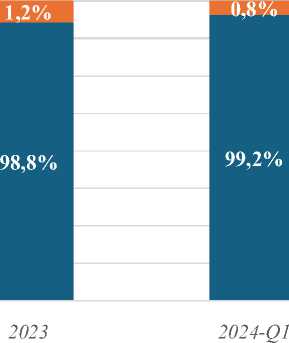

Throughout the period from 2010 to the first quarter of 2024, seasonal workers accounted for about 99 percent of all Central Asian migrants entering the United Kingdom (Fig. 3). Tajik students and highly qualified professionals were the first to open up this migration route, but recently the Tajik contingent has been increasingly dominated by labor migrants, particularly seasonal workers.

The United Kingdom faces one of Europe’s most acute labor shortages, particularly in laborintensive yet low-status branches of the economy.

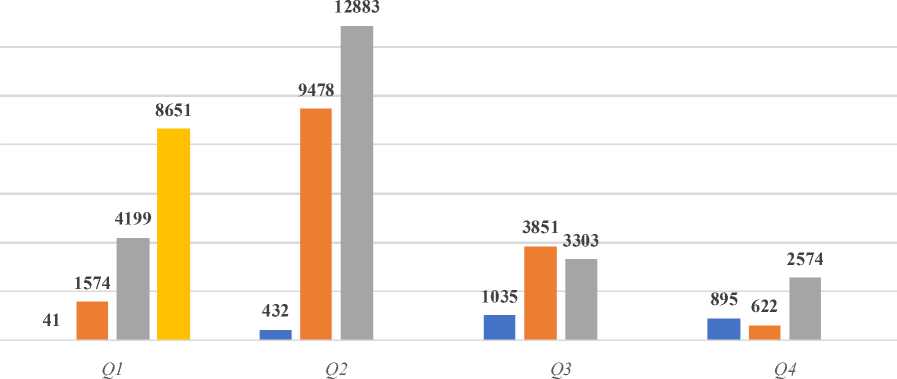

A noticeable inflow of seasonal workers from Central Asia began in the second quarter of

Table 3. Number of seasonal migrants from Central Asian countries in the UK, 2021–2024 Q1, persons

|

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Tajikistan |

Uzbekistan |

|

|

2021 |

519 |

321 |

982 |

581 |

|

2022 |

2 964 |

4 364 |

3 910 |

4 287 |

|

2023 |

5 156 |

7 988 |

5 669 |

4 146 |

|

2024-Q1 |

2 289 |

2 980 |

1 649 |

1 733 |

Note. Compiled by the authors from data in source: [26].

* Kazakhstan ■ Kyrgyzstan ■ Tajikistan ■ Uzbekistan

Fig. 2. Share of seasonal migrants from Central Asian countries in the UK, 2021–2024 Q1, % Note. Compiled by the authors from data in source: [26].

2021, when 432 migrants arrived. The stream expanded to 1,035 in the third quarter and 895 in the fourth quarter of that year. By 2023 the scale of Central Asian seasonal migration had grown dramatically, reaching a peak of about 13 thousand arrivals in the second quarter (Fig. 4).

Licensed recruitment agencies – chiefly Agri-HR and Osrodek-HR – are the principal conduit for bringing seasonal workers from

Central Asia to the United Kingdom under the Seasonal Workers Scheme. Whereas recruitment was once handled largely through Moscow offices, the agencies now operate directly in the region. Training centers and information offices have been established in Tajikistan and Kazakhstan in cooperation with these agencies and local authorities. In Tajikistan, for example, the selection and dispatch of candidates are coordinated by the

Fig. 3. Distribution of migration types among migrants from Central Asian countries in the UK, 2021–2024 Q1, % Note. Compiled by the authors from data in source: [26].

I 2021 ■ 2022 ■ 2023 ■ 2024

Fig. 4. Number of seasonal workers from Central Asian countries in the UK by quarters, 2021–2024, persons Note. Compiled by the authors from data in source: [26].

Migration Service and the Ministry of Labor, Migration, and Employment, but their mandate extends only to Tajik citizens, underscoring the absence of monopoly control over migration channels. Alongside organized recruitment, some Central Asian migrants make their own way to the United Kingdom: the journey costs roughly USD 1,000 to 1,500, and a six-month work contract is signed on condition that the worker returns home when it ends [16].

Agri-HR and Osrodek-HR mainly supply personnel to Pro-Force and Fruitful Jobs. Until 2022 Agri-HR recruited through its Moscow office, but after the start of the special military operation, it shifted operations to the region itself [35]. English language skills are generally not required: interviews are conducted in Russian, and Russian-speaking supervisors are present on the farms [14].

Growing demand has spawned fraudulent schemes. Fruitful Jobs urges applicants to submit forms only through Agri-HR, while the Tajik Migration Service asks that bogus offers be reported. The operator Concordia publishes a list of licensed agencies – six in total, including four additional suppliers [18].

Pre-departure orientation is provided by advisory centers in Tajikistan and by labor mobility centers in Kazakhstan; one such center opened in Turkestan in November 2024 with support from Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Labor, the IOM, and the UK Embassy. According to Ambassador K. Leach, the aim is “to ensure that all workers arrive well prepared” [29].

Social media also shape migration flows: the Telegram channel Work in England has 19,800 subscribers. Experienced migrants share information and often return several seasons in a row without intermediaries, advising newcomers to travel in groups for mutual support [16].

Working conditions typically involve a 40 hour week, weekly pay, a minimum wage of £8.91 per hour, and a working day from 06:00 to about 15:00–16:00 with breaks. Workers are entitled to 14 days’ leave during a six-month contract, which can be taken in cash, and receive free English lessons twice a week [16]. Accommodation – costing £60 per week – is provided close to the workplace: four-person caravans, single rooms, or units for couples, with an on-site gym, sports grounds, and shop.

Migrants report that conditions are markedly better than in Russia: equipped cabins, free laundry, and average food expenses of £35–40 per week. Workers from the CIS communicate in Russian; with East Europeans they use English, which eases contract comprehension but is not essential [16].

A small cohort of highly qualified professionals uses seasonal visas as a springboard for seeking positions in their own fields. Overall, organized seasonal migration to the United Kingdom has become a significant employment channel for Central Asians and illustrates how public institutions, private agencies, and social networks jointly shape migration flows, minimize risks, and raise the returns to labor mobility.

Agriculture is the principal field of employment for migrants from the Central Asian republics in the United Kingdom. According to the UK Office for National Statistics, an average of 96 percent of Central Asian migrants worked in British agriculture in 2021 and again in the second half of 2024 (Fig. 5).

Because labor migration from Central Asia to the United Kingdom is largely channeled through organized schemes, cases of wage arrears and other violations of workers’ rights are rare – unlike the situation in the Russian Federation. One interviewee who had spent five years with private construction firms in Russia before moving to Britain explained, “In Russia I earned around 500 dollars a month; in Britain I made about one and a half thousand in the last month. In Russia you are never sure the employer will pay. There is lawlessness there, whereas in Britain I feel protected by the law” [9].

Central Asian migrants report feeling more comfortable and secure in the United Kingdom despite the language barrier and say they have not encountered ethnic or racial discrimination from law-enforcement bodies or employers. The same respondent recalled, “I never felt safe in Russia, and I faced racial discrimination and harassment both from employers and from police officers” [9]. Another migrant, Sukhrob Ulmasov, who worked in Wales, observed, “We are pioneers of a sort among Tajiks – large groups have not yet gone to Britain for farm work, as far as I know. I can say straight away: local people are friendly to visiting laborers. That is already a big plus” [7].

2,8%

9,9%

97,2%

90,1%

■ Agriculture ■ Other sectors

Fig. 5. Sector of employment of migrants from Central Asian countries in the UK, 2021–2024 Q1, % Note. Compiled by the authors from data in source: [26].

Although the scale of Central Asian migration to the United Kingdom is gradually increasing, it remains relatively modest. The main constraints are the lack of appropriate skills and insufficient knowledge of English [34].

Results. A persistently high – albeit partly concealed – rate of unemployment and chronically low wage levels in the Central Asian republics have long served as classic “push” factors prompting workers to look for jobs abroad. For many years most migrants from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan headed for the Russian labor market, but European destinations – among them the United Kingdom – are now gaining ground.

Labor migration is both an economic and a political phenomenon: it reshapes bilateral relations, strategic partnerships, and the social stability of all parties involved. Since the late 2010s the United Kingdom has intensified its engagement with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan in the field of labor mobility. That shift reflects domestic economic needs – above all, acute post-Brexit labor shortages in agriculture – and the broader recalibration of British migration policy after leaving the European Union.

From the standpoint of the Central Asian governments, expanding migration channels is a foreign-policy instrument aimed at strengthening links with the West, attracting hard-currency remittances, and easing social tensions at home [36].

Whereas early Central Asian migration to the United Kingdom consisted almost exclusively of highly qualified specialists and students, the combination of Russia’s worsening economic climate and Britain’s demand for low-skilled labor has opened the door to seasonal farm workers. Tajikistan, for example, actively encourages this reorientation: in 2021 it concluded agreements with both the United Kingdom and the Republic of Korea on sending seasonal migrants. The resulting flows now move through two main corridors – organized recruitment via the Tajik Migration Service and licensed agencies, and independent, self-financed travel.

Agriculture remains the principal sector of employment for Central Asian migrants in the United Kingdom. Despite the short duration of contracts – typically up to six months – the country has emerged as a significant new destination. It is too early to speak of a wholesale switch away from Russia, yet Russia’s economic difficulties, stricter migration rules, and falling real wages, combined with rising labor demand in Britain, are already diverting part of the Central Asian outflow towards the UK.

Experience shows that well-regulated, organized recruitment systems offer substantial advantages in safeguarding rights and ensuring access to health care. Once migrant workers arrive, British employers are responsible for accommodation, sanitary standards, medical services, and work permits – and must arrange the workers’ return when contracts expire. These provisions both enhance migrant welfare and underscore the importance of cooperative frameworks in maximizing the benefits of labor mobility for all parties.