Turkish teacher candidates’ self efficacies to use listening strategies scale: a validity and reliability study

Автор: Mehmet Kurudayıoğlu, Talha Göktentürk, Emre Yazıcı

Журнал: Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems @imcra

Статья в выпуске: 2 vol.5, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study aimed to develop Turkish Teacher Candidates’ Self-Efficacies to Use Listening Strategies Scale. Therefore, the study was designed in sequential explanatory design, and sequential timing has been followed. First, the interview study was conducted with 40 participants, and the qualitative data were analyzed through content analysis. Subsequently, an item pool was designed via the findings obtained from the qualitative findings and literature review. Afterward, the draft form was applied to Turkish teacher candidates and 345 valid forms were obtained. As a result of the exploratory factor analysis conducted for the data obtained, we determined that the items were collected in four factors in total. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as .927 for the scale. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed in the last stage, and finally, we found that all factors are statistically significant and the obtained model has a good fit. In addition, we determined that the qualitative findings have chronological categorization and the quantitative findings have thematical categorization. This means that thematic categorization to the listening strategies can be more appropriate for listening skills. Consequently, the scale can be used in determining the self-efficacy perceptions of Turkish teacher candidates to use listening strategies. Furthermore, the scale can contribute to similar studies in the literature.

Listening strategies, Turkish teacher candidates, self-efficiency, teacher education, education, social sciences, language teaching, language studies, humanities

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/16010158

IDR: 16010158

Текст научной статьи Turkish teacher candidates’ self efficacies to use listening strategies scale: a validity and reliability study

Listening is a process in which a listener is not only a passive character but also an active character with cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills (Anderson & Lynch, 2008;

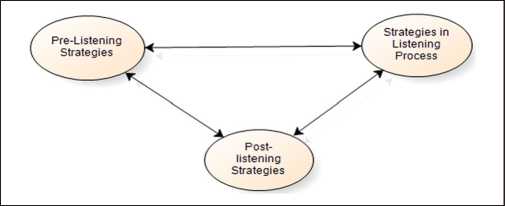

Listening strategies that can be defined as any plan that listeners improve their comprehension or listening performance (Rost & Wilson, 2013) are important elements for improving the listening process (Türkel, 2012). Listening strategies are reported in different classifications, but when the classifications are compared, we can see that the chronological based on the process is the most used classification type as pre-listening, listening, and post-listening strategies in Turkish Education (Yazıcı & Özden, 2017;

The use of relevant strategies has been studied with different subgroups. Awareness of metacognitive strategies can

Creative Commons CC BY: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages .

positively affect the listening comprehension (al-Alwan et al., 2013; Coşkun, 2010) and a significant amount of correlation between metacognitive strategies and emotional intelligence (Alavinia & Mollahossein, 2012). There is a serious relationship between listening anxiety and listening strategies (Golchi, 2012). Teaching metacognitive strategies can positively affect the target groups’ listening comprehension skills (Katrancı & Yangın, 2013; Schunk & Rice, 1984). Finally, metacognitive strategy instruction can provide selfefficacy for listening skills (Rahimirad & Zare-ee, 2015). Although there is a tendency to classified listening strategies with the chronological-based approach in Turkish Education (Yazıcı & Özden, 2017;

Turkish teacher candidates, because of the reasons such as “don’t have a rich environment for listening activities” (Rost & Wilson, 2013), are not able to improve their skills for using listening strategies (Karadüz, 2010). In addition, inside of lessons, they usually apply to passive listening that prevents themselves from becoming active participants in the listening process (Tabak, 2013). Furthermore, inside of the listening process, distraction, boring, being unbiased, and antipathy against the speaker create psychological problems, and some candidates have hearing problems on the physiological side (Emiroğlu, 2013). Furthermore, because of the type of language, listening purposes, and contexts in which listening occur (Anderson & Lynch, 2008), Turkish teacher candidates’ listening process can be difficult. There is a need for studies on which listening strategies can be used to solve the specified problems (Epçaçan, 2013). This need coincides with the studies conducted on different target audiences and emphasizes the importance of listening strategies and selfefficacy for listening against problems encountered during the listening process (Graham, 2006, 2011;

The focus of the present article is on the measurement of the prospective Turkish teachers’ self-efficacies to listening strategies. Many scales have been developed in the literature on listening skills. Especially, because of the importance to create an active listening process, different kinds of scales were developed in different areas such as active listening in medical consultations (Fassaert et al., 2007), active empathetic listening (Drollinger et al., 2006), and metacognitive awareness in listening (Vandergrift et al., 2006).

Purpose of the Study

Based on the findings, the development of the self-efficacy scale for the use of listening strategies of Turkish teacher candidates can provide a pool of data in the development of the skills to use listening strategies. Furthermore, it can contribute to the development of listening skills. Moreover, in this research, we studied for the development of Turkish Teacher Candidates’ Self-Efficacies to Use Listening Strategies Scale. The problem sentences that constitute the objectives of the research can be expressed as follows:

-

1. What is the study group’s self-efficacy for listening strategies?

-

2. Is the measurement tool developed to cover the parameters obtained as a result of qualitative examination valid and reliable?

Method

In this study, the research process has begun with the literature review, which aims to develop the self-efficacy scale for Turkish teacher candidates’ listening strategies. Considering that the obtained data pool would be inadequate during the development of the scale, a more open and inclusive research process was needed. As a result of the literature review, it was decided that only a quantitative research design did not correspond to the aims of the study. Therefore, the study was designed in a mixed method to obtain more in-depth and explanatory results (Creswell, 2009, 2012, 2017; Creswell & Clark, 2015; Lisle, 2011; Morse, 2003; Özden & Durdu, 2016; Punch, 2016).

Qualitative Stage

Participants. The first stage of the study was designed in a case study model and we aimed to determine the self-efficacy of the Turkish teacher candidates who make up the study group for the listening strategies used in the listening process. The framework of the case is to reveal the selfefficacy of the study group for the strategies they use in listening processes. About this purpose, the semi-structured interview method that allowed the researchers to gather indepth data (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2016) was chosen. Questions of the semi-structured interview form were designed with three questions that we are gathering information about listening strategies that are used as pre-listening, listening, and post-listening in line with the literature of Turkish Education (Yazıcı & Özden, 2017; Kurudayıoğlu & Kiraz, 2020). Thanks to that, we wanted in-depth data about the entire listening process. Although Tabak (2013) states that there is no significant difference among grade levels of Turkish teacher candidates’ listening, the Listening Education course that can affect their self-efficacy for using listening strategies is in third grade (Council of Higher Education, 2019). In addition, for gathering in-depth data from the research groups, we decided to involve all grades inside of research process. Finally, we decided to use a purposive sampling method that can allow the researcher to specific study units (Yin, 2011).

We received the verbal consent of the participants. Afterward, the qualitative phase of the study was carried out in Yıldız Technical University Turkish Language Teaching Undergraduate Program. The study group consisted of 10 students from the first grade, nine students from the second grade, 11 students from the third grade, and 10 students from the fourth grade. The interviews were recorded with a voice recorder and decoded. During the interview process, the participants in the study group were informed about the listening strategies, and at the same time, it was ensured that the prior knowledge levels were increased through additional materials and information on the subject, if necessary.

Data collection, analysis process, and reliability of findings. In the first step of the study, interviews were conducted with the study group, which collected qualitative data. While preparing the interview questions, the literature review was made, and after the draft questions were prepared, a field expert was consulted. After this step, the interview form was completed. To create a data pool and to obtain in-depth data from each of the class levels, 10 students from the first grade, nine students from the second grade, 11 students from the third grade, and 10 students from the fourth grade were interviewed, and the data were collected.

Number of agreements

Reliability =------------------------2---------------------.

Totalnumberof agreements + Disagreements

Quantitative Stage

Research universe and sample group. The development of a valid and reliable scale depends on the sample size. Gorsuch (1983) states that there should be at least five participants per variable, and there should be at least 100 participants for each analysis. Bryman and Cramer (1999) argue that, although there is a factor analysis with less than 100 participants, it is appropriate to have at least 100 participants for each analysis. Büyüköztürk (2002) argues that as a general rule, the sample size should be 5 times the number of variables. There are 36 items in the application form of the research.

In this research, every member of the Turkish teacher candidates’ population has an equal and independent chance of being selected and there is no intent to describe specific subgroups. That is why a simple random sampling method (Fraenkel et al., 2012) was used to obtain the sample. To reach a sufficient number of participants, a total of 345 valid forms, 160 participants from Yıldız Technical University Turkish Language Teaching Program, and 185 participants from the Marmara University Turkish Language Teaching Program were obtained. During the application process, we received the verbal consent of the participants.

Research process. In the study, after the literature review, we found that no assessment tool makes Turkish language teacher candidates directly as the target group. Later, we tried to answer the question: “Is the assessment tool developed to cover the parameters obtained as a result of qualitative examination valid and reliable?”

For finding an answer to this question, first findings of the qualitative data reorganized in line with the chronological-based approach (Yazıcı & Özden, 2017;

Kiraz, 2020) via quotations that were taken from interviews. At this point, we take into account the classifications of O’Malley et al. (1989), Vandergrift (1997), and Bacon (1992). Especially, Bacon’s (1992) approach is more suitable for the construction of draft items because of the chronological-based and cognitive-based strategies together. In addition, although we analyzed qualitative data in three main themes, we take into consideration that our subcategories also coincide with active listening strategies that can be summarized in eight main categories: planning, focusing attention, monitoring, evaluating, inferencing, elaborating, collaborating, and reviewing (Rost & Wilson, 2013). Finally, we examined sample scale development studies that involved listening strategies (Drollinger et al., 2006; Fassaert et al., 2007; Vandergrift et al., 2006), and designed our draft item form with taking these studies as an example.

After the organization of the draft item form, whether the content of the items is a representative sample from the domain (Fulcher & Davidson, 2007) was tested by Lawshe’s analysis formula: content validity ratio (CVR) = (Ne – N/2)/ (N/2) (Lawshe, 1975). In assigning experts for Lawshe’s analysis, we sought that experts worked in the field of measurement and evaluation and have knowledge in this area. Finally, we obtained our application form that consists of 36 items. With the completion of the data collection process, explanatory factor analysis with Varimax rotation was made to reveal the theory and infrastructure under the 36 items (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007; Thompson, 2004). To find the internal consistency coefficient (Büyüköztürk, 2002/2018; Özdamar, 2015), Cronbach’s alpha values calculated for each dimension and the total scale. Then, factor-based discriminatory procedures were followed with an independentsample t test (Kelley, 1939). Finally, to determine whether the fit indices are acceptable, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted (Erkorkmaz et al., 2013).

Results

Qualitative Results

As a result of the interviews with the students, the data in the interview were collected under three themes. Following the interview form, the findings were categorized into three main themes as pre-listening listening strategies, listening strategies used during listening, and listening strategies used after listening. In the last stage of the qualitative research part, prospective Turkish teacher candidate’s selfefficacy to use listening strategies modeled based on qualitative findings which were created by open coding (see Figure 1).

As a result of content analysis which was made by open coding, we determined that listening strategies in which participants consider themselves sufficient consist of three themes. About these findings, listening strategies were divided into themes with a process-based perspective. The

Figure 1. Listening strategies.

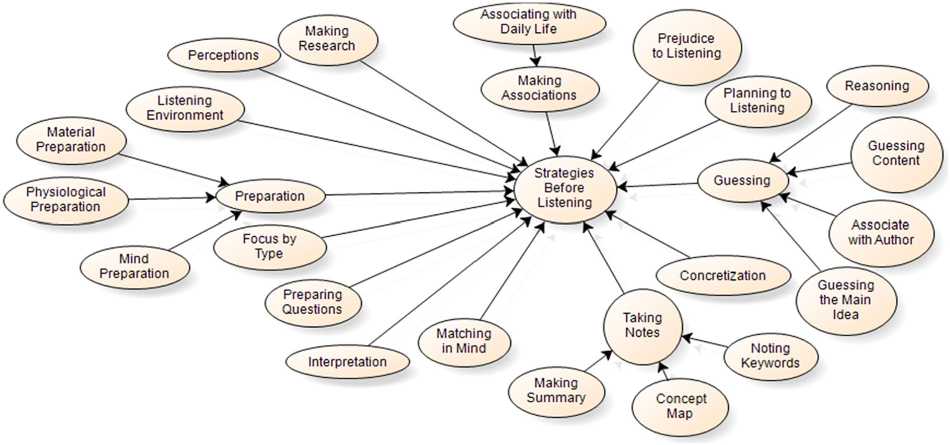

categories included in each theme are presented below (see Figure 2).

The number of strategies that participants in the study group deemed sufficient to use themselves before listening consists of 15 main categories. The Guessing category has Guessing the Main Idea, Associating With the Author, Guessing Content, and Reasoning subcategories. The Note Taking category has Creating Summary, Concept Map, and Taking Notes of Keywords subcategories. The Preparation category has Material Preparation, Physiological Preparation, and Mind Preparation subcategories. Finally, the Making Associations category has one subcategory as Associating With Daily Life.

In line with the findings, participants make their guesses to find the main idea of their listening. Furthermore, they consider themselves sufficient for making associations between their listening and the sender. Furthermore, they also consider themselves sufficient to guess the context of messages that they listen to. Finally, before listening, they consider themselves sufficient to reasoning about the message that they listen to. Based on the detailed findings of the Guessing category, we can say that the study group largely uses the strategies about guessing.

Another main category that is used by participants is Taking Notes. In line with the findings of this part, participants consider themselves sufficient in noting keywords, and they usually use this strategy to improve the efficiency of their listening. Some of the participants emphasized that making a concept map according to their former learnings about the messages would help to a better understanding of the listening process. Finally, in line with former learnings, making a summary is a beneficial strategy to create a better listening process.

In addition, when they prepare for listening to come, participants consider themselves sufficient for providing necessary materials such as a pencil, notepaper, a recorder, and so on. Furthermore, they adjust their sitting and choose the appropriate body position to take notes as physiological preparations. They also clear their minds to gain a better listening process before listening. Finally, inside of the main categories which have subcategories, Making Associations has one category as Associating With Daily Life. This category means that participants consider themselves capable of

Perceptions

Reasoning

Guessing

Preparation

Concretization

Interpretation

Making Summary

Physiological Preparation

Planning to Listening

Listening Environment

Preparing

Questions

Making Research

Guessing Content

Matching in Mind

Prejudice to Listening

Noting Keywords

Focus by Type

Making Associations

Taking Notes

Associating with Daily Life

Concept Map

Material Preparation

Guessing the Main Idea

Associate with Author

Strategies Before Listening

Mind Preparation

Figure 2. Strategies that Turkish teacher candidates consider themselves self-sufficient before listening.

associating the messages they get with daily life thanks to their former learnings.

The other main categories have no subcategories. According to these findings, participants consider themselves sufficient in making research, constructing necessary perceptions, organizing the listening environment as suitable to their needs, constructing their focus according to type, preparing questions to the speaker, interpreting the messages, matching the messages’ notions with their minds via their active vocabulary, concreting the message, planning to their listening, and managing their prejudices to messages before the listening process. Conclusively, participants of the qualitative research part widely use the listening strategies before the listening process (see Figure 3).

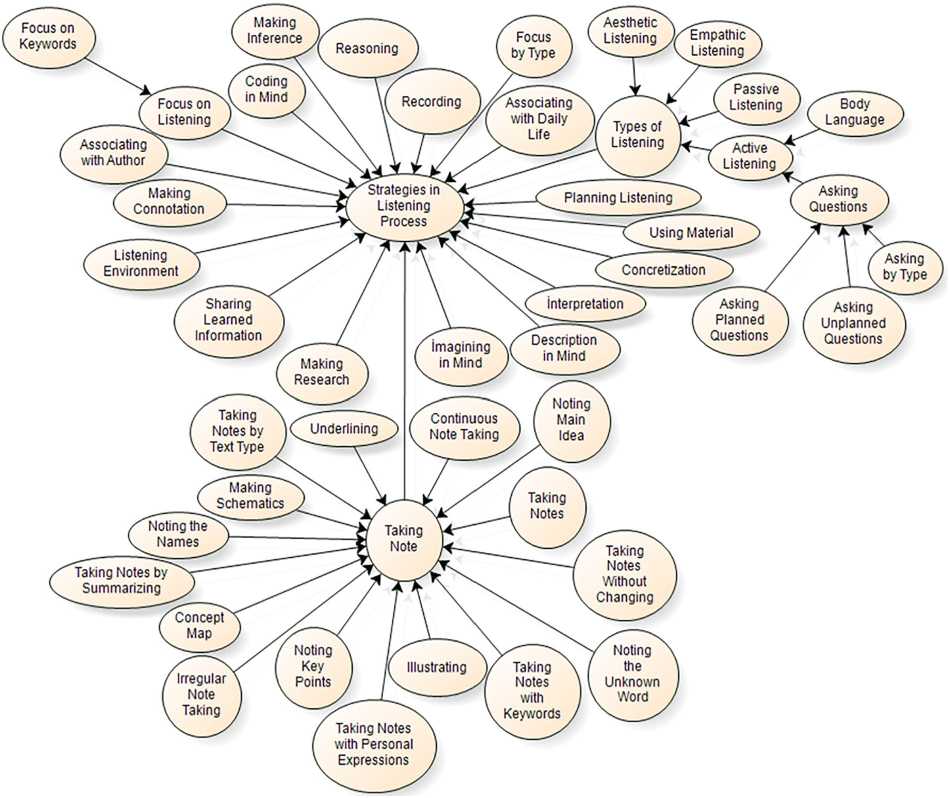

In this part of the study, as a result of content analysis, 20 main categories were determined through the open coding process. Among these categories, Focus on Listening, Taking Note, and Types of Listening have their subcategories. Other main categories have no subcategories.

The Focus on Listening has only Focus on the Keywords subcategory. This category means that participants focus on the keyword in a listening process. They also believe that this strategy makes their listening more efficient.

Taking Note category has more subcategories than any other main categories. According to the findings that were obtained via content analysis, participants consider themselves sufficient in underlining the written forms of listening messages. They are also able to take notes by message type, making schematics which is appropriate to the message, noting the names inside of the message, taking notes by summarizing, creating concept maps, irregularly notetaking, noting key points, taking notes with personal expressions, illustrating their listening, taking notes with keywords, noting the unknown words, taking notes without changing the listening messages, taking notes, noting the main idea of listening messages, and continuously note-taking.

Types of the listening category have four subcategories as aesthetic listening, empathic listening, passive listening, and active listening. Participants use aesthetic listening for obtaining pleasure from their listening. Among the other subcategories, active listening has its subcategories as body language and asking questions. Participants are capable of asking planned or unplanned questions, and they can also ask questions by the type of listening messages. They also use their body language to making their listening processes more effective.

The reasoning is used by the participants throughout the listening process. Some of the participants stated that sometimes they are making interferences about listening messages. When they listen, they also code the messages to their minds. Furthermore, they can associate listening messages with their sender and make connotations. Like the strategies which can be used before listening, participants can organize their environment inside of listening. Furthermore, they share learned information with others and make research via different research tools, such as the internet, inside of listening.

About findings, we determined that participants usually imagine what they listen to throughout the listening and create a description in their minds. In addition, they make interpretations and concretizations. When participants need materials, they can use it, such as a pencil, notepaper, recorder, and so on. Finally, they can plan their listening, associate them with daily life, and focus on by type (see Figure 4).

Reasoning

Recording

Planning Listening

Using Material

Concretization interpretation

Underlining

Concept

Noting

Noting

Illustrating

Points

Taking Notes by Summarizing

Taking Notes by Text Type

Types of Listening

Asking by Type

Listening Environment

Making Research

Body Language

Making Schematics

Making Inference

Strategies in Listening Process

Asking Questions

Associating with Author

Noting the Names

Taking Note

Taking Notes

Coding in Mind

Empathic Listening

Making Connotation

Asking Unplanned Questions

Description in Mind

Associating with Daily Life

Unknown Word imagining in Mind

Noting Main Idea

Asking Planned Questions

Sharing Learned Information

Focus by Type

Focus on Listening

Passive Listening

Irregular Note Taking

Taking Notes Without Changing

Aesthetic Listening

Active Listening

Taking Notes with Personal Expressions

Focus on Keywords

Continuous Note Taking

Taking Notes with Keywords

Figure 3. Strategies that Turkish teacher candidates consider themselves sufficient in the listening process.

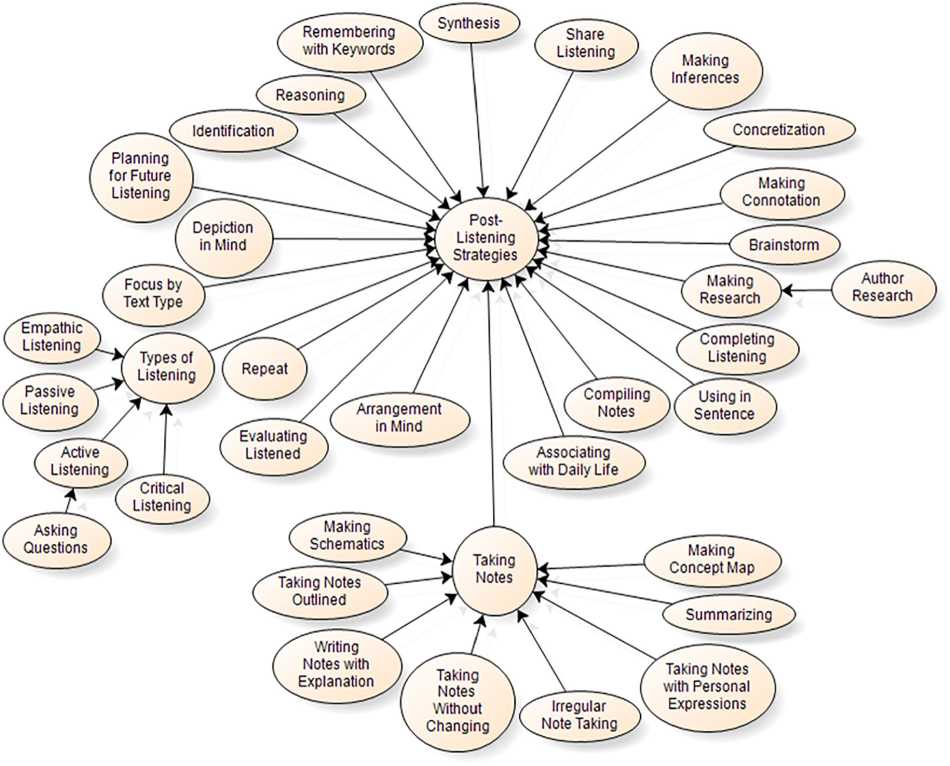

The post-listening strategies consist of 22 main categories. Among these categories Types of Listening, Note Taking, and Making Research categories have their subcategories. The other 19 categories have no subcategories.

Types of the Listening category have four subcategories, such as Empathic Listening, Passive Listening, Active Listening, and Critical Listening. Participants individually stated that they sometimes use these listening types as a strategy to make their listening process more efficient. In addition, the Active Listening category has an “asking questions” subcategory. As a difference, critical listening is used by participants after they listen. In summon, participants of this study use different types of listening depends on conditions.

Taking Notes category has seven subcategories. This category means that participants make schematics, take outlined notes, add them explanations, and they can also take notes without any change. Furthermore, they can take irregular notes and notes with personal expressions. They can summarize a listening message after the listening process, and make a concept map.

Among the categories which have subcategories, Making Research category has only one subcategory as Author Research. This category means that participants make researches about the sender of the listening messages. Participants stated that they gain a deep review of the listening messages thanks to this research. Finally, participants consider themselves sufficient in the other main categories, and they use them to gain a better listening process in the post-listening part.

Reliability level of qualitative findings. In the final part of the qualitative stage, we consulted a field expert to determine the reliability of qualitative findings. Eight of 108 categories took corrections, and categories took final forms as a result of this process. Finally, we found that the reliability ratio of findings is 92.59%, and determined that these findings are

Synthesis

Reasoning

Concretization

Identification

Brainstorm

Repeat

Summarizing

Focus by Text Type

Irregular Note Taking

Remembering with Keywords

Completing Listening

Asking Questions

Making Inferences

Taking Notes Outlined

Making Schematics

Empathic Listening

Types of Listening

Taking Notes

Compiling Notes

Using in Sentence

Making Concept Map

Making Connotation

Evaluating Listened

Making Research

Depiction in Mind

Arrangement in Mind

Author Research

Taking Notes Without Changing

Share Listening

Taking Notes with Personal Expressions

Writing Notes with Explanation

Planning for Future Listening

Passive Listening

Active Listening

PostListening Strategies

Associating with Daily Life

Critical Listening

Figure 4. Post-listening strategies that Turkish teacher candidates consider themselves sufficient.

Quantitative Results

Data collection tool. Self-Efficacy Scale for Listening Strategies of Turkish Teacher Candidates was used as a data collection tool in this stage of research. After the data collection process, we analyzed the quantitative data in line with quantitative analysis methods. The development process of the scale is presented below.

Forming of item pool. To reveal the measurement tool that will be developed to cover the parameters obtained as a result of the qualitative examination, a pool of 50 items was created first from the categories and quotations obtained from the focus group interviews. Lawshe’s (1975) analysis was completed with seven experts from two educational sciences and five Turkish educational fields. Based on the results obtained from Lawshe’s analysis, we gave the final form to the item pool as 36 items (see Table 1).

The x symbol means that there is no problem with this item’s application to the target group. In addition, CVRs were presented inside of the table. According to Lawshe’s (1975) CVR, the acceptable threshold is equal or above from .70. As a result of the analysis, we eliminated 14 items with expert opinion, and 36 items were formed with the application form; 29 items took 1 point and approval of all experts. Afterward, we included the other seven items in the application form as a result of the approval of most experts. At this stage, corrections for non-consensus items were completed following expert opinions. Finally, we eliminated 14 items from the draft form and applied the application form to 345 participants from Yıldız Technical University Turkish Education Department Undergraduate Program and Marmara University Turkish Education Department Undergraduate Program.

Table 1. Lawshe’s Analysis Results.

|

Items Expert 1 |

Expert 2 Expert 3 Expert 4 Expert 5 Expert 6 Expert 7 CVR |

|

Item 1 x Item 2 x Item 3 x Item 4 x Item 5 x Item 6 x Item 7 x Item 8 x Item 9 x Item 10 x Item 11 x Item 12 x Item 13 x Item 14 x Item 15 x Item 16 Item 17 x Item 18 x Item 19 x Item 20 x Item 21 x Item 22 x Item 23 x Item 24 x Item 25 x Item 26 x Item 27 x Item 28 x Item 29 x Item 30 x Item 31 x Item 32 x Item 33 x Item 34 x Item 35 Item 36 x Item 37 x Item 38 x Item 39 x Item 40 x Item 41 x Item 42 x Item 43 x Item 44 x Item 45 x Item 46 x Item 47 Item 48 x Item 49 x Item 50 x CVR (critical) for a panel size ( N ) of 7 is 1 |

x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x 0.714 x x x x 0.429 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x -0.429 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x 0.714 x x x x x x1 x x x x x 0.714 x x x x 0.143 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x 0.429 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x 0.429 x x x x 0.429 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x 0.143 x x x x x 0.714 x x x x 0.429 x x x x x 0.714 x x x -0.143 x x x 0.143 x x x x x x1 x x x x x 0.714 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x 0.714 x x x x 0.429 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x x x x x x1 x -0.429 x x x -0.143 x x x x x x1 x x -0.143 x x x x x x1 0.857 |

Note. CVR = content validity ratio.

|

Table 2. Communalities. |

||

|

Item Names in Draft Form |

Initial |

Extraction |

|

21. I can visualize the message I’m listening to in my mind. |

1.000 |

.662 |

|

15. I can relate the message I’m listening to daily life. |

1.000 |

.661 |

|

13. I can empathize with the characters of the message I listen to while listening. |

1.000 |

.579 |

|

22. After listening, I can make reasoning about the message I listened to. |

1.000 |

.663 |

|

10. I can make inferences about a message I am listening to. |

1.000 |

.681 |

|

31. After listening, I can relate the message I listened to daily life. |

1.000 |

.675 |

|

20. I can take note of the message I’m listening to with my own expressions. |

1.000 |

.617 |

|

34. After listening, I can produce a new message based on the text I listened to. |

1.000 |

.695 |

|

36. I can adapt the message I listen to a different genre (e.g., expressing poetry as prose). |

1.000 |

.668 |

|

35. After listening, I can edit the message I listened to in my mind. |

1.000 |

.686 |

|

30. I can plan my future listening with the preliminary information I get from the message I listened. |

1.000 |

.596 |

|

28. After listening, I can find the aesthetic elements of the message I listen to. |

1.000 |

.535 |

|

1. If I already know the subject of the message I will listen to, I can research the message. |

1.000 |

.757 |

|

2. I check my preliminary information about the content I will listen to. |

1.000 |

.766 |

|

4. Before listening, I can physiologically prepare myself to listen (sleep, hunger, etc.). |

1.000 |

.539 |

|

5. Before listening, I can prepare the materials that will be necessary for me during listening. |

1.000 |

.468 |

|

16. I can use additional materials while listening (post-it, small notepapers, etc.). |

1.000 |

.681 |

|

18. In the message I am listening to, I can write down words that I don’t know the meaning of. |

1.000 |

.653 |

|

19. During listening, I can take notes of the message with using visualizations such as concept map, scheme, picture, table, and so on. |

1.000 |

.689 |

Data analysis. After the formation of the draft form, we obtained 345 valid forms from the participants and analyzed the data with SPSS and AMOS program. Kaiser–Meyer– Olkin (KMO) test, Bartlett’s test, Varimax rotation technique, and explanatory factor analysis were used to analyze the data, which were gained by the application process. Subsequently, item-total and item-remainder correlations were examined, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated, and confirmatory factor analysis was performed.

Results of validity analysis. To measure the validity of the 36 items obtained through Lawshe’s analysis and to develop a theory based on the structure of the items and to reveal the relationship between the factors for the analyses to be carried out in the next steps, we carried out exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation to reveal the theory and infrastructure under the 36 items used in the application process (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007; Thompson, 2004). As a result of the KMO and Bartlett’s test performed to determine the suitability of the data for factor analysis, we found that KMO = .931 and Bartlett’s value was significant (x2 = 3,200.8 8 8, p < .0001). In line with the obtained data, we concluded that the sample size and structure were factorable. In the first stage, the results obtained by calculating the communalities obtained through principal components analysis were reported (see Table 2).

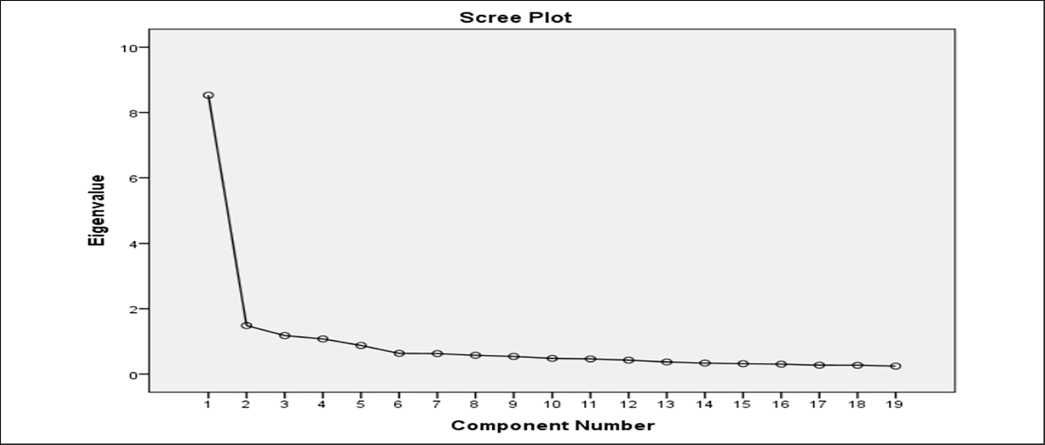

When the extraction values of the items are examined, we determined that all of them are higher than .30 and the highest extraction value is .766. Due to the high values obtained, we continued factor analysis without the elimination of any item. Afterward, the variance ratio and the findings of factor analysis were presented below (see Figure 5 and Table 3).

We determined that the scale has a four-factor structure with factor analysis made with principal components analysis based on Eigenvalue 1. The first of these factors explains 22.474% of the total variance, the second explains 17.888%, the third explains 12.585%, and the fourth explains 11.641%. Four factors explained 64.587% of the total variance of the scale. The analyses were carried out with the obtained multifactor structure (see Table 4).

When we look at the item which was obtained by Varimax rotation, there is no item lower than .30. Items 15, 22, 10, 31, 20, 35, 30, 28, 4, and 5 took values from more than one factor. Even so, the difference between them is not less than .10. Because of that, we decided to keep items at the factor where the most value was taken. Finally, we presented factors that were obtained and items of factors in Table 5.

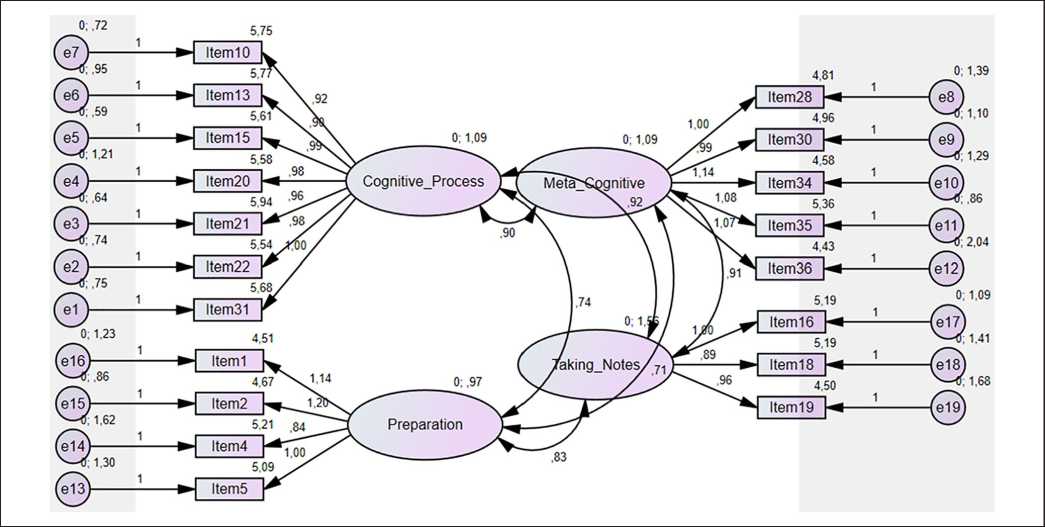

About these findings, the cognitive processes factor in listening is composed of seven items (21, 15, 13, 22, 10, 31, and 20), the metacognitive listening factor is composed of five items (34.36, 35, 30, and 28), the preparatory factor for listening is four items (1, 2, 4, and 5), and note-taking factor in listening consists of three items (16, 18, and 19). There is no inverse item on the scale. The scale consists of 19 items.

In the naming of the factors, we examined items of each factor and then we made the final decision for all factors; therefore, it was decided that to name the first factor as the cognitive process, the second factor as the metacognitive listening, the third factor as preparation to listening, and the fourth factor as the taking notes in listening. As a result, the increase in the scores related to that factor and the increase in the total score were evaluated as positive self-efficacy perceptions of Turkish teacher candidates to use listening

Figure 5. Scree Plot.

Table 3. Component Analysis.

The internal consistency coefficient of the scale is quite high. The alpha values are as follows: for the first subdimension of the scale, a = .900; for the second sub-dimension, a = .842; for the third sub-dimension, a = .766; for the fourth sub-dimension, a = .756; and for the total scale, a = .927. According to Buyukozturk (2002/2018), an alpha value greater than .70 is necessary for the scale to be accepted as reliable. According to Özdamar (2015), the scale of .60 < a < .70 is sufficiently reliable. Therefore, the scale was found to be reliable. After the analysis, factorbased discriminatory procedures were performed, and 27%

Table 4. Rotated Component Matrix.

Component

Table 5. Factors and Items of the Factors.

|

Factors |

Number of items Items |

|

Cognitive process Metacognitive listening Preparation to listening Note taking in listening |

7 items 21, 15, 13, 22, 10, 31, 20 5 items 34.36, 35, 30, 28 4 items 1, 2, 4, 5 3 items 16, 18, 19 |

Table 6. Factors and Items of the Factors.

To determine whether there is a significant difference between the arithmetic means of the upper 27% and lower 27% groups, we found that the difference between all groups was statistically significant. The results show that scale total and factor scores are distinctive ( p < .001). Afterward, to determine whether there is a correlation among factors, we made Pearson’s correlation analysis and presented the results in Table 9.

As a result of Pearson’s correlation analysis, there are significant correlations among factors and total scale. These findings indicate that factors of the scale are related and they measure the same structure (see Figure 6 and Table 10).

As a result of the analysis data, the χ2/ df value is below 5. This means that the fit indices are acceptable. Goodness-of-fit index (GFI) value is .903, and this also means that there is an acceptable fit. Furthermore, the comparative fit index (CFI) value is .919 and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value is below 0.08. Finally, the fit indices revealed that the scale has a good fit (Erkorkmaz et al., 2013).

Discussion

In this research, we developed a measurement tool to cover the parameters obtained as a result of qualitative analysis. The 50-item draft form prepared to determine whether the measurement tool is valid and reliable was presented to the opinion of seven experts and turned into a 36-item application form by Lawshe’s analysis. After removing 14 items

Table 7. Independent-Samples t Test Results to Determine the Distinctiveness of Scale Items.

-

1. About the Eigenvalue in the self-efficacy scale of Turkish teacher candidates to use listening strategies, the total variance explained by four factors is 64.587%. As a result of the Varimax rotation technique, the items are sufficiently distinctive. Factor loads of items vary between .468 and .766.

-

2. We named the first factor as “cognitive processes in listening,” the second factor as “metacognitive listening,” third factor as “preparation to listening,” and the fourth factor as “taking notes in listening.”

-

3. To the first factor (cognitive processes in listening), the Cronbach’s alpha value is .900. To the second factor (metacognitive listening), the Cronbach’s alpha value is .842. To the third factor (preparation to listening), the Cronbach’s alpha value is .766. To the fourth factor (taking notes in listening), the Cronbach’s alpha value is .756. To the scale itself, the Cronbach’s alpha value is .927. Calculated Cronbach’s alpha values are higher than .70. This means that the scale and its factors are consistent and reliable.

-

4. The analyses showed that for all items, factors, and total scores of the scale, there is a statistically significant difference. The factors and total scores of the scale are distinctive. This is means that the scale can be used as a reliable tool.

-

5. As a result of item-total and item-remaining analyses, correlations of all items in the scale were found to be significant. Therefore, we determined that all the items of the scale are in the same structure.

-

6. The fit indices obtained as a result of confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the scale has a good fit.

Table 8. Independent-Samples t Test Results to Determine the Distinctiveness of the Scale Scores.

t test

|

Item |

Groups |

N |

M |

SD |

SE |

t |

df |

p |

|

Cognitive |

Upper |

93 |

6.83 |

.168 |

.017 |

30.993 |

184 |

.000 |

|

process |

Lower |

93 |

4.30 |

.771 |

.080 |

|||

|

Metacognitive |

Upper |

93 |

6.39 |

.382 |

.040 |

36.690 |

184 |

.000 |

|

listening |

Lower |

93 |

3.38 |

.693 |

.072 |

|||

|

Preparation to |

Upper |

93 |

6.29 |

.370 |

.038 |

35.629 |

184 |

.000 |

|

listening |

Lower |

93 |

3.47 |

.670 |

.069 |

|||

|

Taking notes in |

Upper |

93 |

6.58 |

.328 |

.034 |

40.289 |

184 |

.000 |

|

listening |

Lower |

93 |

3.20 |

.739 |

.077 |

|||

|

Total |

Upper |

93 |

6.34 |

.307 |

.032 |

33.619 |

184 |

.000 |

|

Lower |

93 |

3.97 |

.606 |

.063 |

|

Table 9. |

Correlational Findings Among the Factors and Scale. |

||||

|

Factors and scale |

Factor 1: Cognitive process |

Factor 2: Metacognitive listening |

Factor 3: Preparation to listening |

Factor 4: Taking notes in listening |

Total scale |

|

Factor 1: |

Cognitive process |

||||

|

r |

.610 |

.610 |

.567 |

.907 |

|

|

p |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

n |

345 |

345 |

345 |

345 |

|

|

Factor 2: Metacognitive listening |

|||||

|

r |

.610 |

.466 |

.464 |

.754 |

|

|

p |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

n |

345 |

345 |

345 |

345 |

|

|

Factor 3: |

Preparation to listening |

||||

|

r |

.610 |

.466 |

.464 |

||

|

p |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

||

|

n |

345 |

345 |

345 |

||

|

Factor 4: Taking notes in listening |

|||||

|

r |

.567 |

.464 |

.464 |

.746 |

|

|

p |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

n |

345 |

345 |

345 |

345 |

|

|

Total scale |

|||||

|

r |

.907 |

.754 |

.754 |

.746 |

|

|

p |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

n |

345 |

345 |

345 |

345 |

|

Figure 6. Confirmatory factor analysis results of the scale.

Table 10. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Indexes for Model Fits.

|

χ 2 |

df |

p |

χ 2/ df |

GFI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

|

627.022 |

146 |

.000 |

4.295 |

.903 |

0.919 |

0.072 |

Note. GFI = goodness-of-fit index; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

Unique to this study is suggesting a thematic approach to the classification of prospective Turkish teachers’ self-efficacy perceptions to use listening strategies. The qualitative findings of the study show differences when we compare them with quantitative findings. In the qualitative stage, listening strategies have three themes as the strategies used before, during, and after listening in line with related literature (Yazıcı & Özden, 2017; Kurudayıoğlu & Kiraz, 2020; Doğan, 2016). This stage is evaluated with a chronologicalbased approach. Contrarily, after the quantitative process that was conducted by explanatory factor analysis which was made to explore the dimensions underlying the data (Field, 2009), the functional side of listening strategies came forward. Thanks to this result, we suggest that functional classifications for further researches on listening strategies could create more useful data to a researcher. Finally, this result can also be interpreted, as functionalbased classifications (O’Malley et al., 1989; Vandergrift, 1997) should not be neglected, whereas chronological-based classification is widely used in Turkish Education (Yazıcı & Özden, 2017;

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The scale can only be used for determining prospective Turkish teachers’ self-efficacy to use listening strategies. However, according to the research findings, the self-efficacy scale of Turkish teacher candidates to use listening strategies is a valid and reliable scale, and the scale can be used to measure prospective Turkish teachers’ self-efficacy perceptions about the strategies they use in listening processes. Besides, it can be used to determine which variables the Turkish teacher candidates’ self-efficacy toward the strategies they use in their listening processes depend positively or negatively. The scale can contribute by providing a data pool in the investigation of variables that affect self-efficacy perceptions toward listening strategies and variables that may affect related self-efficacy perceptions as an independent variable.

Appendix

Turkish Teacher Candidates’ Self-Efficacies to Use Listening Strategies Scale.

|

Order in the |

Order in the application |

|

|

Factors |

scale |

form İtems 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

|

Preparation to 1. |

1. Dinleyeceğim bir metnin konusunu önceden biliyorsam metinle |

|

listening 2. 3. 4. |

ilgili araştırma yapabilirim. [=If I already know the subject of the message I will listen to, I can research the message.]

[=I check my preliminary information about the content I will listen to.]

dinlemeye hazırlayabilirim. [=Before listening, I can physiologically prepare myself to listen (sleep, hunger, etc.).]

materyalleri hazırlayabilirim. [=Before listening, I can prepare the materials that will be necessary for me during listening.] |

|

Cognitive 5. process 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. |

[=I can make inferences about a message I am listening to.]

empati kurabilirim. [=I can empathize with the characters of the message I listen to while listening.]

[=I can relate the message I’m listening to daily life.]

[=I can take note of the message I’m listening to with my own expressions.]

[=I can visualize the message I’m listening to in my mind.]

yapabilirim. [=After listening, I can make reasoning about the message I listened to.] |

(continued)

Appendix. (continued)

|

Order in the |

Order in the application |

|

|

Factors |

scale |

form İtems 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

|

11. |

31. |

Dinleme sonrasında dinlediğim metni günlük hayatla |

|

Taking notes 12. |

16. |

ilişkilendirebilirim. [=After listening, I can relate the message I listened to daily life.] Dinleme sırasında ek materyallerden faydalanabilirim (postit, |

|

13. |

18. |

küçük not kâğıtları ve benzeri). [=I can use additional materials while listening (post-it, small notepapers, etc.).] Dinlemekte olduğum metinde anlamını bilmediğim kelimeleri |

|

14. |

19. |

not alabilirim. [=In the message I am listening to, I can write down words that I don’t know the meaning of.] Dinleme sırasında metni kavram haritası, şema, resim, tablo vb. |

|

Metacognitive 15. |

28. |

görselleştirmeler kullanarak not alabilirim. [=During listening, I can take notes of the message with using visualizations such as concept map, scheme, picture, table, etc.] Dinleme sonrasında dinlediğim metnin estetiki unsurlarını |

|

listening 16. |

30. |

bulabilirim. [=After listening, I can find the aesthetic elements of the message I listen to.] Dinlediğim metinden aldığım ön bilgilerle gelecekteki |

|

17. |

34. |

dinlemelerimi planlayabilirim. [=I can plan my future listening with the preliminary information I get from the message I listened.] Dinleme sonrasında dinlediğim metinden hareketle yeni bir |

|

18. |

35. |

metin üretebilirim. [=After listening, I can produce a new message based on the text I listened to.] Dinleme sonrasında dinlediğim metni zihnimde düzenleyebilirim. |

|

19. |

36. |

[=After listening, I can edit the message I listened to in my mind.] Dinlediğim metni farklı bir türe uyarlayabilirim (örneğin şiiri düz |

|

yazı olarak ifade etme vb.). [=I can adapt the message I listen to a different genre (e.g., expressing poetry as prose).] |

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Talha Göktentürk ф

Anderson, A., & Lynch, T. (2008). Listening . Oxford University Press.

Aytan, T. (2011). The effects of active learning techniques on listening ability (Thesis No. 280654) [Doctoral dissertation, Selçuk University Educational Science Institute]. Council of Higher Education Thesis Center.

Bacon, S. M. (1992). Phases of listening to authentic input in Spanish: A descriptive study. Foreign Language Annals, 25(4), 317–333.

Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (1999). Quantitative data analysis with SPSS 8 release 8 for windows: A guide for social scientists . Routledge.

Büyüköztürk, Ş. (2002). Factor analysis: Basic concepts and using to development scale. Educational Administration in Theory

Büyüköztürk, Ş. (2018). Sosyal bilimler için veri analizi el kitabı istatistik, araştırma deseni SPSS uygulamaları ve yorum [Data analysis handbook for social sciences statistics, research design SPSS applications and interpretation]. Pegem Academy. (Original work published 2002)

Coşkun, A. (2010). The effect of metacognitive strategy training on the listening performance of beginner students. Online Submission, 4(1), 35–50.

Council of Higher Education. (2019a, June 10). Türkçe öğretmenliği lisans programı [Turkish teaching undergraduate program]. egitim_ogretim_dairesi/Yeni-Ogretmen-Yetistirme-Lisans-Programlari/

Council of Higher Education. (2019b, June 10). Yükseköğretim bilgi yönetim sistemi [Higher education information management system].

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

Creswell, J. W. (2017). Karma yöntem araştırmalarına giriş [A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research] (M. Sözbilir, Ed. & Trans.). Pegem Academy. (Original work published 2014)

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2015). Karma yöntem araştırmalarının tasarımı ve yürütülmesi [Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research] (Y. Dede & S. B. Demir, Ed. & Trans.). Anı Publication. (Original work published 2006)

Doğan, Y. (2016). Dinleme eğitimi . Pegem Academy.

Drollinger, T., Comer, L. B., & Warrington, P. T. (2006). Development and validation of the active empathetic listening scale. Psychology & Marketing , 23 (2), 161–180.

Emiroğlu, S. (2013). Turkish teacher candidates’ opinion about listening problems. Adıyaman University Journal of Social Sciences Turkish Education Special Issue, 6(11), 269–307.

Epçaçan, C. (2013). Listening as a basic language skill and listening education. Adıyaman University Journal of Social Sciences, 6(11), 331–352.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS . SAGE. (Original work published 2000)

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2012). How to design and evaluate research in education . McGraw-Hill. (Original work published 2000)

Fulcher, G., & Davidson, F. (2007). Language testing and assessment an advanced sourcebook . Routledge.

Golchi, M. M. (2012). Listening anxiety and its relationship with listening strategy use and listening comprehension among Iranian IELTS learners. International Journal of English Linguistics, 2(4), 115–128.

Gorsuch, R. L. (1983). Factor analysis . Lawrence Erlbaum.

Graham, S. (2006). Listening comprehension: The learners’ perspective. System, 34(2), 165–182. system.2005.11.001

Graham, S. (2007). Learner strategies and self-efficacy: Making the connection. Language Learning Journal, 35(1), 81–93.

Graham, S. (2011). Self-efficacy and academic listening. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(2), 113–117. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.04.001

Karadüz, A. (2010). The evaluation of listening strategies of Turkish language and primary student teachers. Erciyes University Journal of Social Sciences, 1(29), 39–55. tr/tr/pub/erusosbilder/issue/23763/253285

Kassem, H. M. (2015). The relationship between listening strategies used by Egyptian EFL college sophomores and their listening comprehension and self-efficacy. English Language Teaching, 8(2), 153–169.

Kelley, T. L. (1939). The selection of upper and lower groups for validation of test items. In A. W. Ward, H. W. Stoker, & M. Murray-Ward (Eds.), Educational measurement origins, theories and explications, Volume II: Theories and applications (pp. 63–70). University Press of America.

Kurudayıoğlu, M., & Kana, M. F. (2013). Türkçe öğretmeni adaylarının dinleme becerisi ve dinleme eğitimi özyeterlilik algıları. Mersin Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi , 9 (2), 245–258.

Kurudayıoğlu, M. & Kiraz, B. (2020). Listening strategies. Journal of Mother Tongue Education , 8 (2), 386–409.

Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28(4), 563–575. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

Lisle, J. (2011). The benefits and challenges of mixing methods and methodologies: Lessons learnt from implementing qualitatively led mixed methods research designs in Trinidad and Tobago. Caribbean Curriculum, 18, 87–120.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis . SAGE. (Original work published 1984)

Ministry of National Education. (2019, June 10). Öğretmenlik mesleği genel yeterlilikleri. [=General qualifications of the teaching profession]

Morse, J. M. (2003). Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 189–209). SAGE.

Özbay, M. (2015). Anlama teknikleri: II dinleme eğitimi [=Comprehension techniques II: listening training]. Öncü Kitap. (Original work published 2009)

Özdamar, K. (2015). Paket Programlar ile İstatistiksel Veri Analizi-1 [=Statistical Data Analysis with Package Programs-1]. Nisan Kitapevi. (Original work published 1997)

Özden, M. Y., & Durdu, L. (2016). Eğitimde Üretim Tabanlı Çalışmalar İçin Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri [=Qualitative Research Methods for Production-Based Studies in Education]. Anı Publication.

Punch, K. F. (2016). Introduction to social research quantitative & qualitative approaches (D. Bayrak, H. B. Arslan, & Z. Akyüz, Trans., 3rd ed.). Siyasal Kitapevi. (Original work published 1998)

Rost, M., & Wilson, J. J. (2013). Active listening . Pearson Education.

Siegel, J. (2015). Exploring listening strategy instruction through action research . Springer.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics . Pearson Education. (Original work published 1996)

Tabak, G. (2013). The evaluation of Turkish teacher candidates’ listening styles in terms of some variables. Mustafa Kemal University Journal of Social Sciences Institute, 10(22), 171–181.

Thompson, B. (2004). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis . American Psychological Association.

Türkel, A. (2012). Techniques for teaching listening skills: An evaluation. Buca Faculty of Education Journal, 34, 128–141.

Vandergrift, L. (1997). The comprehension strategies of second language (French) listeners: A descriptive study. Foreign Language Annals, 30(3), 387–409. /j.1944-9720.1997.tb02362.x

Yazıcı, E., & Özden, M. (2017). Öğrencilerin dinleme süreçlerinde kullandıkları dinleme stratejilerinin belirlenmesi. International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching , 5 (4), 308–327.

Yıldırım, A., & Şimşek, H. (2016). Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araştırma yöntemleri [=Qualitative research methods in the social sciences]. Seçkin Publication. (Original work published 1999)

Yin, R. K. (2011). Qualitative research from start to finish . The Guilford Press.