Ust-Tsilma female headdress: description and use (mid 19th to early 21st century)

Автор: Dronova T.I.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145304

IDR: 145145304 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.2.132-141

Текст обзорной статьи Ust-Tsilma female headdress: description and use (mid 19th to early 21st century)

Russian Priestless Old Believers (the Pomors) living in Ust-Tsilemsky District of the Komi Republic is a compact confessional group, which has the exonym of “Ust-Tsilemy”. They have been living in the European Northeast, surrounded by different ethnic groups (the neighboring Izhma Komi, and the Nenets), for over three centuries, and preserve the Old Orthodox faith and a distinctive culture. Despite the stable existence of traditional forms of dress until the mid-1950s, folk clothing, as a manifestation of their culture, has never been the subject of a special study. The development of folk clothing was undoubtedly fostered both by endogenous processes associated with the search and elaboration of distinctive ethnic features, and by exogenous processes resulting from the impact of foreign cultures.

At present, women of the older generation in the Ust-Tsilemsky District wear exclusively traditional clothing (for everyday use, festive clothing, and clothing for prayer), while young women may wear both modern and traditional clothing. In the post-Soviet period, people began to sew festive sarafan dresses and shirts for children of all ages to be worn at folk-festivals. Male and female festive clothes are made according to old models for participants of folklore groups active in the Ust-Tsilemsky District and in the places where

Ust-Tsilma communities live: in the towns of the Komi Republic, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Arkhangelsk, and Naryan-Mar.

This article examines and analyzes female headdress. Headdress with the name of shapka (‘hat’) was exclusively male in the traditional culture of Ust-Tsilma dwellers. Women wore bonnets and decorated headdresses on solid bases, which did not have a single common name. Headdress in the form of hat became a part of the clothing of the Ust-Tsilma women only in the 1970s. In the past, the word shapka was used in the colloquial speech of local residents, for example, for designating the capacity of a woman not to respond to the gossip of the villagers, “to hang a hat on one’s ear”. The phrase “put on a deaf hat” described the man living in the house of his wife. The phrase, “He will take off his last hat” characterized an unselfish, generous person; careless lightheaded people were called “sewn-on sima”*.

The main female headdress was the headscarf, which was worn from infancy to the last days of life; all deceased females were buried wearing headscarves. Wearing a headscarf conformed to the norms of behavior for a girl/ woman. The expression “to lose the scarf from one’s head” described girls of loose conduct.

The severe climate of the Far North predetermined the range of basic economic activities for Ust-Tsilma dwellers, which did not include cultivation of technical crops (flax, hemp) necessary for textile production. Homemade and industrial textiles were brought to the region by merchants, who would come by winter roads to the fairs in the Pomor villages (Dronova, 2011: 13). All pieces of headdress that we have observed, including headscarves, were made of industrial textiles.

Early information about the types of headdress that existed at the Pechora has not survived. The sources for this study were headscarves, bonnets, and headbands made no earlier than the mid-19th century, which are a part of the collection of A.V. Zhuravsky (kept in the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera)), as well as field materials of the present author’s, and objects from the family collections of the Ust-Tsilemsky District’s residents.

Types and varieties of headdress

Headdress of women and girls is represented by headbands, ribbons, bonnets, and headscarves. Girls’ headdress included numerous headbands, which were worn throughout entire Russia. Currently, despite the frequent use of traditional clothing in Ust-Tsilma villages, the tradition of wearing headbands has been lost. This type of headdress is described using the collection of

Zhuravsky, which includes fragments of two types of headbands:

-

1) pozatylen or headband for the back of the head, made of linen fabric dyed in red, with lining. Consists of ochelye (the part for the forehead) and the back part; embroidered with beads of white, blue, black, and green colors; bears an independent and complete decorative pattern on each part;

-

2) forehead-band made of a narrow dense strip of golden embroidery.

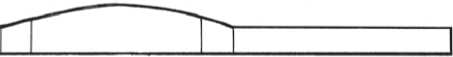

The most expensive headdress for girls was khaz , a wide headband with strings (Fig. 1). This name of the headdress is known only in the Ust-Tsilma villages, and is associated with wide gold-interwoven ribbon-galloon, which was called “khaz” in the Russian North and was also used for decoration of sarafans . Forehead bands were cut out of dense textile embroidered with golden or silver threads, and trimmed with wide galloons, which was decorated at the bottom with river pearls used for these purposes throughout the entire north and northwest of Russia. The side parts closer to the back of the head were cut out of silk or semi-silk fabric of the same kind, and the ribbons were cut out of another kind of fabric. The headdress was fastened to the back of the head using hidden strings; ribbons served as a decorative element; they were tied in a half hitch (Fig. 1).

Festive headdress for girls also included a small headscarf, or kerchief, folded into a band. If it was tied around the head leaving the top of the head open, this meant that the girl was ready for marriage; and married women completely covered their heads with the headscarf. At the semantic level, the head-decoration of a girl who had reached adulthood, and the way she tied her headscarf-band, were the symbols of girlhood, beauty, freedom, and dignity. The use of a headscarf-band as a head decoration for maidens occurs among all dwellers of the Russian North, as well as the Old Believers of the Altai (Fursova, 1997).

At the turn of the 19th–20th centuries, headdress in Ust-Tsilma villages was of various types, which were divided into subtypes: kokoshnik of the morshen type, kokoshnik on a solid base, kokoshnik-sbornik, samshura, and povoinik. The area where kokoshniks and samshuras were worn mostly coincides with the Old Novgorod area and territories that for a long time were under the influence of Novgorod, including the areas in the Pechora River basin (Lebedeva, Maslova, 1956: 24–25). Kokoshniks and samshuras were widely used in Cherdynsky Uyezd of the Vologda Governorate, where golden embroidery was common. As a part of other imported goods, pieces of headdresses were brought by the merchants from Cherdynsky Uyezd to the Pechora (Maslova, 1960: 111–112). The types of headdress mentioned above are available in the collection of Zhuravsky. Unfortunately, the collector did not specify their local names, providing

b

а

Fig. 1. Festive khaz . a – general view; b – structure.

“povoinik”. In its shape, poboinik is a version of sbornik, which was in use in the Arkhangelsk Governorate until the 1930s. It is one of the versions of the Old Russian kokoshnik. Some families preserved poboiniks made of old textiles and embroidered with gold and silver; according to the owners, they had been used until the end of the 19th century. At present, dressmakers sew poboiniks from modern brocade according to traditional models. The Ust-Tsilma version of this headdress uses exclusively common Russian names. Currently, headdress of two types is commonly used in the Ust-Tsilemsky District (the local names are given):

-

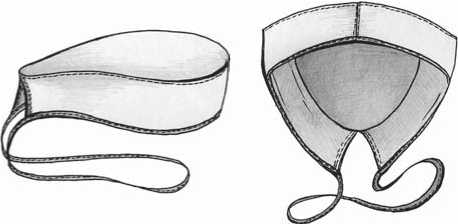

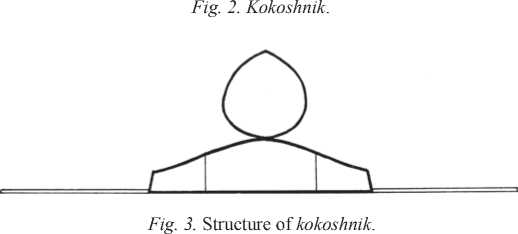

1) kokoshnik – soft low cap with lining, which has a drop-shaped bottom, band, strings on the back of the head, and trimming of denser textile along the edge (Fig. 2). This headdress resembles the common Russian povoinik , and that name is given to the object in the inventory by Zhuravsky. In Ust-Tsilma villages, the headdress of this kind is called kokoshnik . Its Ust-Tsilma version is a low

bonnet, the size of which is regulated by a special cut: the edges on the back of the head remain free, and overlap each other when they are tied (Fig. 2, 3). It is worn by married women and widows. Festive kokoshnik is made of expensive textiles; everyday kokoshnik from cotton or satin. Kokoshnik is always covered by a headscarf, which is tied with a knot at the back of the head;

-

2) poboinik – wedding headdress on a solid base. Its name is derived from the common Russian word

a ribbon ( otdirysh ) of textile with “golden” embroidery, which is fastened around the head from the top by a special knotless method: the ends of the ribbon are taken forward from the back of the head, twisted, separated on two sides, and hidden under the base. This method of decorating the headdress with a ribbon seems to be typical of the Ust-Tsilma tradition. When the bride was moving to the house of her groom, a large rep shawl folded diagonally was placed upon the poboinik of the bride; it was not tied, and its ends loosely hung on both sides.

The headscarf was, and still remains, the most common female headdress. The value of the headscarf depends on its size and texture of fabric. Kanafatnye and large rep headscarves are especially valued (Fig. 4); the Ust-Tsilma women measure their sizes in “quarters” (a distance from the pinky finger to the thumb of wide open palm). Headscarves of square form were large (some were 12–14 quarters); when being worn, their ends would reach the level of the knees. The Ust-Tsilma

women call such headscarves starinnye (‘age-old’) or samoluchshiye (‘the very best’).

Headscarves are of several kinds. Their local names are derived from the words indicating the texture of the textile and the method of production, and sometimes coincide with the commonly known Russian names. In Russian, there is a word plat , meaning ‘headscarves and kerchiefs different in size and manner of wearing’ (Russkiy traditsionnyi kostyum…, 1998: 213). The Ust-Tsilma women use this word only for festive large and medium-sized headscarves. They tie the headscarf over kokoshnik with a half hitch at the back of the head. Such headscarves are still in demand among Ust-Tsilma women. “Decorated headscarves were very much cared for. Women would wear small rep headscarves for weddings; they would sit on benches and were afraid to crumple them, and they could also have torn them, as they were thin and flimsy. Brocade headscarves would be worn for parties at people’s homes, small rep, silk, and satin headscarves.

At such parties, many people, up to fifty, would gather; they would stay in two houses, and they sometimes sweated. Silk and satin headscarves could be washed; but rep headscarves were never washed, they were only hung out in the open air in summer time” (FMA (field materials of the author), recorded in the village of Chukchino in 2002 from P.G. Babikova, born in 1932). “On feast-days, the day before Lent, regardless of whatever frost there might be, women in these rep and kanafatny headscarves would walk in the streets; they would dress nicely, and would not tie any other headscarf. Wearing beautiful reindeer-fur coats with cuffs and collar, shirts made of cloth or stof fabric, women would gather by the road near each other’s house in groups of five to ten people, sing songs, and watch the guys taking the girls horse-riding. Our father had reindeer, and he would harness reindeer, and we would drive the reindeer” (FMA, recorded in Syktyvkar in 2009 from M.N. Epishina, born in 1921 in the village of Chukchino). “There were many golden or rep headscarves brought to Tsilma from Arkhangelsk in the fifties [the 1950s – T.D. ] . We would go to Arkhangelsk and bring headscarves from there; in Ark hangelsk, women wouldn’t wear them anymore, but would use them instead of tablecloths to cover tables; but here, women would wear them and really wanted to buy them” (FMA, recorded in the village of Rochevo in 2010 from I.G. Ananina, born in 1932).

In Ust-Tsilma villages, the use of the following types of headscarves has been observed:

Aglitsky – this name was used in Ust-Tsilma villages for small half-woolen shawls; their main background was red; white, blue, and green were used in floral ornamentation along the rim;

Kanafatny plat – a silk headscarf with geometric ornamentation consisting of large squares, with their centers decorated with “golden” thread (Fig. 5). In some places, such a headscarf was called konovatka or konovatny (Lavrentieva, 1999: 41). It was a strip of fabric, which was used by the inhabitants of the Vologda Territory as a wedding veil, and by the Ust-Tsilma women as a headscarf. Two headscarves could have been made from a single strip of fabric. The kanafatny headscarves were considered to be “rich”; if golden thread was present in the headscarf, it was called “golden” plat, and the Ust-Tsilma women referred to it as “honored”. Such a headscarf in a woman’s wardrobe was associated with wealth: “Not every woman had a kanafatny headscarf, only the rich. The bride would be dressed in such a headscarf the day after the wedding; women would wear it to gorka festivities; it was a very honored headscarf. Now very few of them are left” (FMA, recorded in the village of Ust-Tsilma in 2008, from I.P. Tomilova, born in 1932). “A golden headscarf was considered kanafatny; our mother did not have one. Very wealthy people, who would go on trips and buy them for their wives and

Fig. 4. E.N. Toropova showing rep shawls.

Fig. 5. N.A. Matveeva wearing a kanafatny headscarf.

daughters, had kanafatny headscarves; but now they are not produced anymore” (FMA, recorded in the village of Chukchino in 2004, from A.I. Durkina, born in 1912);

Parchovy – length of brocade; began to be used as a headscarf in the mid-1960s; the thread was raveled at the edges of the headscarf, and short tassels were made, or ready-made tassels of silk threads were sewn to the edges;

Pukhovy – a headscarf knitted of goat-down; the Ust-Tsilma women started to commonly use them relatively lately, only in the mid-20th century. At the present time,

Fig. 6. I.I. Nosova and A.A. Chuprova showing redninnye headscarves.

chafranenye ), and orange-light blue. Black is common for all the above combinations. White-blue, white-pink, and white-orange headscarves are decorated with two-colored ornamentation of various kinds. Small flowers in the center, large bouquets/ garlands of flowers in the corners, and a large stylized floral ornamentation of curls along the rim, form the basis of decoration for all headscarves. Some headscarves were additionally decorated with embroidery. Headscarves differed in size (small, medium, or large);

Sorochka – small headscarf of cotton or satin for everyday wear. This is tied under the cheeks with a half hitch called soroka *;

Shalyushka – headscarf of average size, of staple textile or wool; it is used for wearing on weekdays, and a headscarf of silk or cashmere is worn on Sundays and feast-days (Fig. 7). The headscarf was considered to be festive if it had tassels of downy shawls of various sizes, including kerchiefs, are in demand;

Redninny – a half-woolen or cotton headscarf, most often green and blue with a multicolored printed design; its central ornamental motif is a paisley pattern, or small flowers (Fig. 6). Such headscarves were a part of the ritual outfit: they were used for joint prayers, and at the betrothal of the bride in the marriage ritual. In the past, headscarves of the Ust-Tsilma women had smooth edges without tassels, since people regarded tassels as sinful, “Tassels were not sewn to the headscarves that would be worn to prayer; it was a sin. It is as if demons sat on tassels; so in the past, they would say that you cannot decorate the clothing in which you pray with pendants. Headscarves with tassels are only put on when one wants to dress up, to go to gorka festivities or to house parties; but not when people stand in front of the icons” (FMA, recorded in the village of Ust-Tsilma in 2004 from A.A. Chuprova, born in 1928). Currently, headscarves are decorated with tassels;

Repsovy plat – festive headscarf of silk or half-silk, “the fabric on the right side was distinguished by small rounded ribs formed by a double drive of the weft (rep weave) or by the difference in the thickness of weft threads and warp threads (false rep weave)” (Lyutikova, 2009: 71). Such headscarves were common throughout the entire Russian North. They have a distinctive pattern, with its elements becoming larger from the center towards the edges, with curls different in shape and size, and different sets of colors. Rep headscarves of the following sets of colors prevail in Ust-Tsilma villages: red-green, blue-orange, green-lilac with the local name silk or woolen threads; sometimes, women decorated industrially manufactured headscarves with such tassels themselves, thus making them festive;

Shalch a – fairly worn headscarf or small shawl, still suitable for use.

The Ust-Tsilma women wore all headscarves folding them diagonally. The method of attachment depended on the age and status of the owner. Infant girls’ heads were completely covered with headscarf; the ends were crossed under the chin and fastened behind the neck. After seven years of age, the girls would wear the same headscarf on weekdays and feast-days, tying it with the soroka half hitch; and only in their teenage years they would start wearing headbands. On feast-days, during street festivities and while walking around the village, the girls were allowed to tie two headscarves: one was folded into a band, and was tied on the back of the head beneath the braid, leaving the top of the head open; another one covered the head from the top with the headscarf tied under the chin, “In spring, girls would start strolling in the streets on feast-days; it is cold outside, and they would tie the headscarf po golovy (‘the underscarf’) as a band, and they would put on light-colored sorochka po kofty (‘the outer scarf’), and would tie it under their cheeks with the soroka knot. In spring, when the river becomes clear of ice, it was cold in open places. The girls would always wear light-colored headscarves— they protected from the wind a little” (FMA, recorded in Syktyvkar in 2009, from M.N. Epishina, born in 1921 in the village of Chukchino of the Ust-Tsilemsky District).

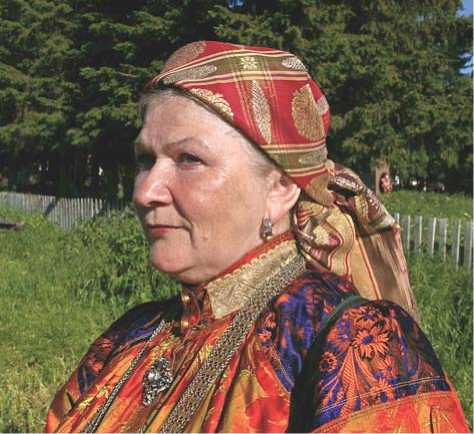

Traditionally, married women and elderly women had to cover their heads at all times of the day with the headscarf. Outside, they would wear two headscarves, which can be conventionally divided into the outer scarf and underscarf; or, according to the Ust-Tsilma terminology, po golovy and po kofty , “On such days [weekdays – T.D. ] , married women would tie small headscarves over kokoshniks: staple or cotton headscarves were tied po golovy, while large shawls would be worn po kofty, tied on top of them” (FMA, recorded in the village of Koroviy Ruchei in 2004, from S.M. Durkina, born in 1926).

The Ust-Tsilma women always paid much attention to how the headscarf, especially the underscarf, was tied; the criteria for a proper tying were equal ends, and a straight line along the ochelye headband. On feast-days and at evening parties, girls and young married women were allowed to open the hair slightly along the ochelye headband, and tie a headscarf-ribbon slightly higher than usual. Married women were required to always hide their hair completely under kokoshnik and headscarf. Even today, people would say about a woman who tied the headscarf above her forehead, “she is tied like an Izhemka”* / “in the Izhma way”, which means “wrong”, “not in the Ust-Tsilma manner”. If the headscarf was tied unevenly on some woman, any person could come and fix it; this was not considered impolite—on the contrary, it was welcomed. For everyday wear, headscarves were tied with a knot at the back of the head, when the ends were left loose or tucked from the top behind the knot.

In winter, early spring, and late autumn, women would wear large headscarves made of wool or cashmere (shawls) together with outer clothing. The Ust-Tsilma women had a special way of wearing and tying shawls: the ends of the shawl in front were crossed, folded backwards, and fastened with a knot at the back of the head. In the past, the knot was tied on the top of the head; “high” fastening according to the Ust-Tsilma vocabulary was considered to be “very honorable”, and preferable. Everyday and festive headscarves were worn in this way. A woolen headscarf ( shalyushka ) was worn together with outer clothing, and was fastened with a half hitch under the chin; while a worn-out headscarf ( shalcha ) was used in spring or autumn for household work within the yard.

Functions of headdress and adornments

A headscarf was the first gift to an infant girl, which she received from her godmother during the baptism, along with a baptismal cross and a belt. In everyday life, a girl/ woman would wear cotton or satin headscarves made out of a piece of industrially produced textile; and on

Fig. 7. U.I. Chuprova wearing a shalyushka .

feast-days and Sundays, she would wear woolen or silk headscarves. A silk headscarf would be tied on a girl the first time in her teen years when she became a participant in youth gatherings and people would say about her that she “was becoming a bride”. At that same time, she was allowed to use hair-adornments and festive headbands.

“The braid is a girl’s beauty”, the people would say. Before getting married, the girl would plait one braid by twisting the strands of hair towards the outer side (away from herself). People would learn about girl’s physiological maturity from the way she arranged her hair: the braid-adornment was replaced with the ribbon, while festive ribbons became decorated with beads. On weekdays, girls would plait the braid in the usual way; on feast-days they would plait a special braid from four strands of hair (the trupchata braid), and decorate it with brightly colored ribbon. Another adornment was a silk headscarf, which was folded into a band and tied around the head. The Ust-Tsilma girls would buy ribbons from the Cherdyn merchants, or receive them as gifts from potential suitors. Such a gift was given publicly, usually at gatherings; the very fact of offering raised the status of the girl as compared to the rest of the girls, even if the giftgiver was not her eventual suitor. In ritual communication, the guys who wanted to express outrage at the behavior of a bride, would cut off her ribbon/braid. For example, if a girl repeatedly refused to dance with a guy at the gatherings, the guy might shorten her ribbon and even her braid. One of the informants described such an incident which occurred in mid-1950s, “When Kondraty Konikhin tried many times to invite me to dance at the gathering, and I kept refusing him, he just cut off my braid right at the gathering. He cut a lot, about a quarter. I hated it. I used to sing and liked to dance very much. He cut it off and thought that I would not go to the gatherings, but I kept going anyway, and then the braid grew back. <…> Girls and guys did not laugh at me” (FMA, recorded in the village of Chukchino in 2000, from P.G. Babikova, born in 1932). For a bride, shortening her braid was a relatively severe punishment; it was believed that it assaulted her dignity. Such an attitude towards stubborn brides was manifested everywhere; for example, to humble the excessive pride of the bride, the Russian guys from Zaonezhye agreed between themselves not to invite her to dance for the entire evening (Kuznetsova, Loginov, 2001: 25).

Despite the skeptical attitude of the Old Believers to wearing adornments, and despite the warnings of elders

Fig. 8. O. Samarina wearing a khaz .

about future torments for foppery in the afterlife, wealthy families would always prepare for the weddings of the girls by assembling the dowries and sewing the outfits. By the age of majority, most of the brides had brooches, silver chains, golden rings and earrings ( chuski ), and also copper/gilded cufflinks. Metal adornments were considered to be good protective amulets. Another hair adornment was flag , a construction of colored satin ribbons attached to the wire with which the flag was attached to the braid.

Khaz – a wide headband, which brides would wear to weddings, walk around the village in the summer, and participate in the gorka round dance festivities, was considered to be a festive headdress (Dronova, 2013a). Khaz was a mandatory headdress of girls during adulthood; its presence indicated the wealth of the girl’s family (Fig. 8). During outdoor walks, the girls would cover their shoulders with large rep headscarves or cashmere shawls. A guy could pull off the headscarf from the girl whom he was attracted to, so she would not refuse him when he sent the matchmakers. If the girl rejected the guy, the headscarf was not returned; this was not forbidden by tradition.

By the early 1930s, khaz appears to have been out of use, and fancy headbands were worn by girls of eight or ten years of age, “Khazes were sewn from the lines [gold-plated ribbon – T.D. ] ; they were ripped off of old sarafan and sewn. During the collectivization, young people began wearing kerchiefs; they began to consider khaz ugly and old-fashioned; then, little girls, from eight to ten years old, would use them until worn out. They would parade on the streets like brides” (FMA, recorded in the village of Sinegorye, from M.I. Kucherenko (Nosova), born in 1923 in the village of Ust-Tsilma).

Married women would completely hide their hair under the headscarf. They would plait two braids (at the temples) by twisting the strands of hair inwards (toward themselves), and fasten them around the head using a ribbon or rope ( gasnik ). If the braids were thin, a roll ( keet ) was placed over the forehead, and a kokoshnik was put on top. In the past, widows who did not want to re-marry stopped wearing kokoshniks , and village matchmakers no longer considered them as potential brides. At present, kokoshniks are worn even by single old women “to keep warm”. A headscarf was always tied over the kokoshnik . Fancy headscarves were worn and stored carefully; this is why they are well preserved, and are used by the Ust-Tsilma women even today.

Among the Ust-Tsilma dwellers, a headscarf was regarded as the cover not only of the woman, but also of the entire family. Wearing pious clothing and headscarves, which were considered protective, was necessary while working with livestock, which was the main asset of the family. Together with headscarf, a ritual shirt kabat was worn. According to popular beliefs, “One shouldn’t milk a cow without wearing a headscarf—milk will disappear”; “Fancy clothes were not worn in the barn, good clothing is for wearing in public, protective clothing would be for the barn; old people knew well and took care of cows, wearing kabats; it is only now that young people live indiscriminately” (FMA, recorded in Chukchino village in 2003, 2004, from P.G. Babikova, born in 1932).

A headscarf was associated with cover and protection, although it was believed that malicious sorcerers could inflict damage through headscarves. According to strong conviction, eretniki [malicious sorcerers – T.D. ] could cast a spell on the headscarf and leave it in a public place, and the person who picked up the headscarf would pay for that with his own health.

Women collected headscarves for their own hour of death; after death, relatives gave the headscarves away, requesting prayers for the deceased. When the coffin with the deceased was being brought to the cemetery, it was covered with a festive headscarf. After the burial, this headscarf was given to the goddaughter or the closest female relative. It was believed that if that headscarf was returned to the house of the deceased, another person might die in this house.

According to the common Russian tradition, the headscarf was the wedding symbol of “covering” (“hiding”) of everything that had to do with the newlyweds during all stages of the ritual (Dronova, 2013a: 111). After ensuring that a girl consented to marry, a guy would act as the initiator of matchmaking. The sign of the mutual agreement was the exchange of pledges: the girl would give the guy a zadatok (“an advance”), usually her personal things: a golden ring or sarafan . In return, the groom would give her a headscarf, which she would start to wear even before matchmaking: she would put on this headscarf for going out, and happily tell her friends about the proposal; from the headscarf, the villagers would learn of the agreement. “Since the guy gave the headscarf, he will soon send the matchmakers” (Maksimov, 1987: 345). The exchange of gifts “sarafan–headscarf” symbolized the readiness of young people for family life, the agreement of the girl to become a wife, and the guy’s obligation to take his chosen one under his protection. Sometimes it so happened that after the exchange of pledges the girl would unexpectedly jilt the guy. In this case, the offended groom would not return the “advance” and would announce the deception in the following way: he would tie the advance to the shaft bow of the harnessed horse and would drive the horse the entire day around the village, which was considered to be a disgrace for the girl. If a girl who did not want to marry an unloved guy committed suicide (drowned herself), she would leave her headscarf as a sign of her departure from this life next to the ice-hole or on the shore.

Gift-giving of headscarves also occurred at matchmaking. During the meal, the bride would thank each male from the groom’s family for participating in the ritual, and would give him a headscarf. From that moment, she had to wear a headscarf, and was forbidden to eat with the groom: “you cannot eat with your fiancé before the wedding”. It was believed that at all stages of the wedding ritual the headscarf protected the bride from envious people and ill-wishers.

A headscarf was used for inviting the guys to participate in the wedding ritual as groomsmen: at a farewell party, the bride would tie a red headscarf ( odirok ) around the neck of each of them, and sew scarlet ribbons to the sleeves of their caftans.

The headscarf was the main attribute of the wedding day. It covered the bride’s head from morning till noon, when the most important rituals of transition (betrothal and bringing the girl to the bath house) were performed; holding her headscarf, the father would take the bride and “hand her over” to the groom together with her headscarf; during the first day, the newly married couple would hold on to the ends of the headscarf to show their unity.

If the wedding was performed without a church ceremony*, with the parents’ blessing, the headdress was replaced with the wedding headdress after the bath house ritual. Before taking the bride to the table to the groom, the bride’s hair was braided with two braids, and she was dressed in povoinik ( poboinik ), on top of which the otdirysh band was attached. The bride remained dressed in povoinik until the moment the newlyweds were taken to the ground floor of the house, where they retired for some time during the wedding. After that, the povoinik was changed to the married headdress— kokoshnik and headscarf. This ritual definitively confirmed the entry of the girl into the group of married women.

In the case that the wedding was to be performed in the edinoverchesky (coreligionist) church, the bride would go there wearing girl’s khaz headband, and only after the wedding was her hair braided, and she dressed in povoinik. As late as the 1920s, the headscarf with which the bride was covered, was folded into a band in the church, and bride’s mouth was covered with it; it was taken off after leaving the ground floor of the house. Tying up the bride’s mouth with the headscarf is an ancient custom in which silence symbolizes a lifeless state and, in the case of a wedding, the temporary “death” of the bride. In the stories of informants about the behavior of the bride in groom’s house until the newly wedded couple was taken to the ground floor of the house, it is noted that the bride “would sit as if lifeless”, “frozen” (Dronova, 2013a: 143). After staying on the ground floor, where the first marital intercourse took place, the wedding headdress was replaced by everyday kokoshnik; for the first time, the bride would tie the headscarf in a manner of married women. After the rituals of “untying” the mouth and replacing the headdress, the bride would become cheerful, would eat food, and communicate with the guests; but she would not participate in dances, and would not sing. The function of the custom was to prevent girl’s talkativeness in her status of wife.

On the second day of wedding, crepes ( olabyshi ) were the obligatory dish. These were always brought to the newlyweds covered by headscarf, or a piece of cloth. On this day, a golden headscarf would be tied on the head of the young wife. Unlike the previous day, the bride was expected to radiate happiness, sing, have fun, and try all the dishes she was offered.

In self-identification of Ust-Tsilma dwellers, folk clothing has always been one of the most important components of culture, like faith, language, and territory. It is very important that nowadays, young dwellers of

Ust-Tsilma wear traditional clothes only on special occasions, and they are sewn according to the traditional cut. Therewith, they strictly observe all the rules relating to the color palette of the costume (including headdress), tailoring, and wearing.

In the 1990s, folk culture started to be actively revived in the villages. At present, the headdress poboinik is worn not only by brides on their wedding days; it has become a part of the folk costume of girls participating in the popular gorka round dance (Fig. 9). The girls three to seven years of age, who are brought to the place of gorka round dancing, are also dressed in this way (Dronova, 2010: 108–109). This is a violation of tradition; but the elders welcomed this innovation, believing that this would motivate the Ust-Tsilma dwellers to preserve traditional folk clothing and to use it. The khaz headdress is starting to be used again.

For Ust-Tsilma dwellers, who are surrounded by other ethnic groups, folk costume is a sign of their belonging to the Russian people, an expression of their ethnic consciousness. Currently, women wearing the Northern Russian sarafan and poboinik are positioned in the towns of the Republic of Komi as Ust-Tsilma dwellers (the local identity). For the residents of the Republic of Komi, the Ust-Tsilemsky District is known as the land where the famous festival of gorka is celebrated, where folk clothes are an indispensable part of authentic traditional festivities.

Fig. 9. Popular gorka festivities.

Conclusions

Trying to escape to remote frontier forests and establishing their secluded life in villages, the Old Believers recognized only correct Christian clothing as acceptable popular dress. Headdress, which preserved Old Russian forms, performed an important semantic role in ritual practices. Headdress reflected the aesthetic tastes of the Ust-Tsilma dwellers, and served as indicators of the economic status of the owners.

The Ust-Tsilma women followed their preferences in the selection of a color palette for the headdress. Despite the prohibitions common in Old Believers’ environment, brightness and diversity of textile colors in girls’ headbands and wedding headdress were maintained; the so-called golden embroidery, expensive bright shawls and headscarves, hair adornments, and ribbons were frequently used.

The analysis of the female headdress used by the Old Believers of Ust-Tsilma has shown that some types of headdress were not only distinguished by specific local names, but also by the character of their cut and their methods of attachment to the head. For example, among the Ust-Tsilma women, the name “kokoshnik” is applied to the common Russian povoinik , while the word “poboinik” ( povoinik ) designates the kokoshnik . Unlike the Northern Russian kokoshnik with high forehead part in the shape of high crown, which was not covered with the headscarf, the Ust-Tsilma kokoshniks were sewn in the form of a low soft cap with strings; they were always worn together with headscarves which were placed on top of kokoshniks and tied on the back of the head.

A local version of the girls’ festive headdress khaz was associated by its name with gold-interwoven ribbongalloon, which was used in other Northern Russian areas for decoration of sarafans . At the same time, everyday girls’ headbands were identical to the Northern Russian headbands.

Great importance in the Ust-Tsilma tradition was given to headdress through which the transition of the girl into married life was visually confirmed during the wedding rituals. For example, at the Pechora, povoinik was put on the bride on the first day of wedding for the period of moving from the parents’ house to the groom’s house. Only after the ritual of podklet (‘the ground floor of the house’), the povoinik was replaced by kokoshnik and a headscarf. Headscarf as a cover was an indicator of the married status of the woman; it reliably protected her health and contributed to maintaining overall wellbeing of the family. The headscarf was the most important attribute of the costume; it served as protective amulet, and was used in the rituals filled with magical symbolism.

Old headscarves, which were made in the mid and late 19th century, are still preserved as family heirlooms; they are worn by the women who participate in folk festivities.

The way they were worn in Ust-Tsilma showed a certain specificity: the inhabitants of Central Russia and the Russian North most often used rep headscarves as festive cover-ups, while the Ust-Tsilma women used them for covering their heads over the kokoshnik and tied them with a knot at the back of their heads.