Вчитывая женщину ("Государство" 454d)

Автор: Протопопова Ирина Александровна, Гараджа Алексей Викторович

Журнал: Schole. Философское антиковедение и классическая традиция @classics-nsu-schole

Рубрика: Статьи

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.12, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

В статье анализируется фраза из платоновского «Государства», давно вызывавшая недоумение и споры у издателей и переводчиков: οἷον ἰατρικὸν μὲν καὶ ἰατρικὴντὴν ψυχὴν [ὄντα] τὴν αὐτὴν φύσιν ἔχειν ἐλέγομεν· οὐκ οἴει; (R. 454d1-3 Burnet). Означает ли ἰατρικὴν τὴν ψυχὴν ‘способную к врачеванию в душе’ женщину-врача, или это место «безнадежно испорчено» (Slings) и женское окончание в ἰατρική является недоразумением? Авторы дают краткий свод исправлений и их обоснований у различных издателей и комментаторов и предлагают свое собственное толкование данного фрагмента. Оно базируется на философском контексте данной фразы и связано с платоновским переопределением «природы» и уяснением эйдоса «иного» и «тождественного» (R. 453b5-456a4). Фраза о «враче и враче в душе» вписывается в этот контекст, только если считать этих «врачей» противоположными в физическом смысле, но родственными в социальном. Исходя из такой перспективы, ἰατρικὸν μὲν καὶ ἰατρικὴν τὴν ψυχὴν логично прочитываются как взаимоотношения иного (мужского и женского) внутри тождественного (склонности к врачеванию).

Платон, женщина-врач, "государство", природа, эйдос

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147215770

IDR: 147215770 | DOI: 10.21267/schole.12.2.07

Текст научной статьи Вчитывая женщину ("Государство" 454d)

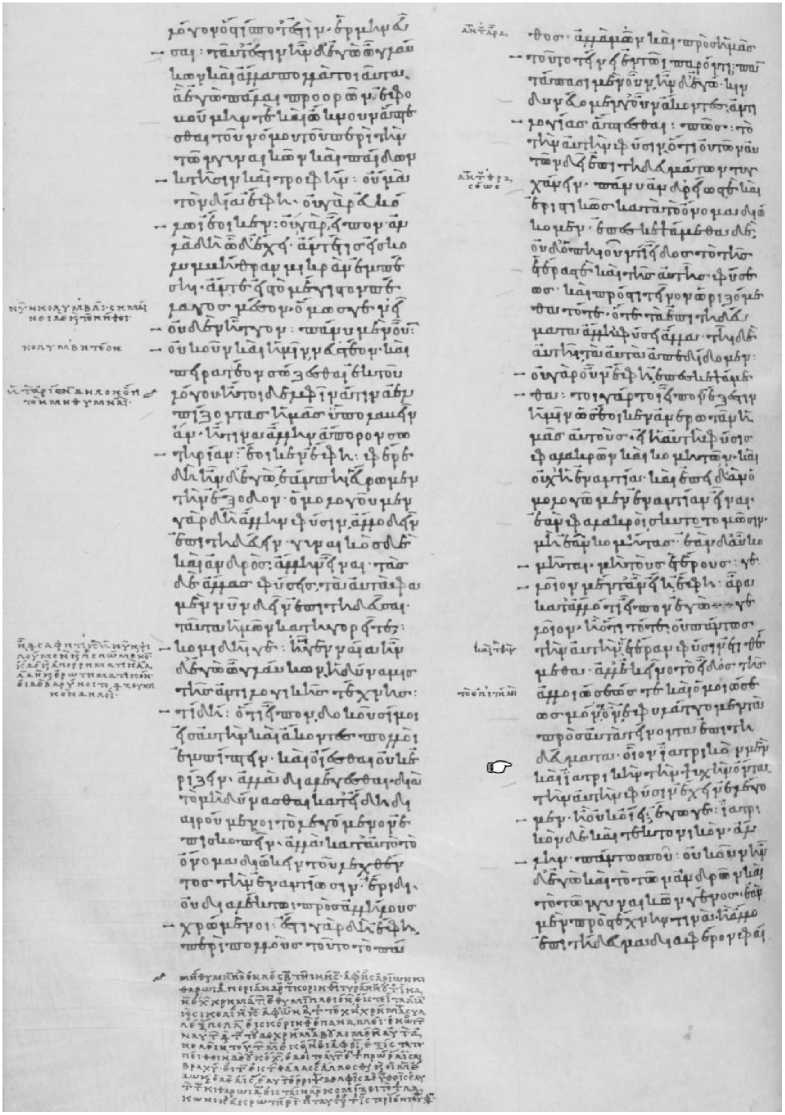

A passage from the Fifth book of Plato’s Republic, οἷον †ἰατρικὸν µὲν καὶ ἰατρικὴν τὴν ψυχὴν ὄντα† τὴν αὐτὴν φύσιν ἔχειν ἐλέγοµεν· ἢ οὐκ οἴει; (Rep. 454d1–3; cf. a picture below, p. 431), has long since caused much confusion and debate amongst editors and translators. Against the above reading in all the primary manuscripts,1 most 19th-century editors2 were inclined to pick καὶ ἰατρικὸν from a weaker manuscript tradition, comparing it to the first ἰατρικὸν (or even ἰατρὸν, inferred from Ficino’s or Cornarius’ Latin versions3) and arriving at a hairsplitting distinction of ‘doctor’ and ‘doctor in soul, i.e. at heart’, or, in Chambry’s rather prolix translation (1934), ‘un homme doué pour la médecine et un homme qui a l’esprit médical’.4 Alternatively, Hermann (1852) reads καὶ ἰατρικὴν, following Stephanus (1578) and in his turn followed by Burnet (1905) and later editors, the only difference between the three being their treatment of ὄντα: Hermann emends it to ὄντας, Stephanus to ἔχοντα, Burnet secludes it altogether.5 All three yield an opportunity to read a woman into the passage.

An opportunity that may well be ignored, as in Stephaniana : “medicum, qui revera faceret medicinam, et eum qui animum haberet medicinae studiis aptum, eademne natura praeditos habere diceremus?” Or else grasped at, as in Shorey’s translation (1930, based on Hermann’s text): “a man and a woman who have a physician’s mind have the same nature”.6

Jowett and Campbell explain ἰατρικὴν in the best manuscripts (which they emend to ἰατρικὸν) as the result of scribal desire to avoid dittographia , and believe that “the singular ὄντα is accounted for by attraction to the nearest word” (1894, 3.221–2). On a more refined level, they treat the repetition of the same word with masculine ending as an anticipation of contrasting identity and difference, the Same and the Other, in the dialogue; at the same time, they would not blame Plato with stylistic “clumsiness of assuming at the very beginning incidentally the general proposition which he has to prove, viz. the aptitude of women for all pursuits” (ibid.).

In the same vein, Slings argues “against introducing women capable of being doctors at this stage of the argument”—at this exact stage, since a female doctor does surface later on (γυνὴ ἰατρική, 455e5) (2005, 83). Slings’ excellent note on this “hopelessly corrupt” passage is unfortunately too sketchy to be overall consistent;

mostly, he is inclined to support Adam’s stripped-down reading: οἷον ἰατρικὸν µὲν καὶ ἰατρικὸν τὴν αὐτὴν φύσιν ἔχειν ἐλέγοµεν.

This rather awkward repetition of the masculine ἰατρικός, as we have seen, may be interpreted as a marker hinting at the discussion of identity and difference. Why, then, should we avoid the supposedly “pre-emptive” reading of a woman into the passage in question: this “clumsiness” may well serve as another marker planted by the author.

Provided we acknowledge the opposition between masculine and feminine forms, ἰατρικός vs. ἰατρική, as intended in the original text, how should we interpret ἰατρικὴν τὴν ψυχὴν? Can we indeed assume that Plato speaks here of male and female doctors? The latter might have been in need of a further specification with an accusativus relationis τὴν ψυχήν, since, if we take at face value Hyginus’ account (fab. 274), women, along with slaves, were legally forbidden to learn the art of medicine in Athens of Plato’s times until one Hagnodike caused the change of the law, allowing women to at least practice obstetrics.7 To be sure, Hyginus is a late author ( c . 150 CE), and his account does not fully agree with Plato’s own references to slave physicians and particularly to Athenian midwives, with their art of maieutics .

Whatever philological or literary approach we try, we cannot do without heavily drawing on the philosophical context of the passage under discussion. When the question whether a woman may be engaged in the same activities as a man is raised in the Republic , Socrates (speaking on behalf of the opposers) recalls the basic principle agreed upon at the very beginning, when he and Glaucon set out the foundation of their polis (cf. 369e–370c): everyone should mind only their own business in accordance with their nature (453b5). And since there is by nature a great difference between women and men, each must be prescribed a corresponding occupation.

And now, as Socrates remarks on behalf of his imaginary opponents, a question is being raised that contradicts his and Glaucon’s erstwhile foundations. Socrates is aware of the complication and “the need to try and swim out of the argument”, ἡµῖν νευστέον καὶ πειρατέον σῴζεσθαι ἐκ τοῦ λόγου (453d9–10). He stipulates that “formerly, we most manfully and eristically chased after the names, arguing that natures not the same should not engage in the same pursuits, but totally missed to consider what is the eidos of different and same nature (Τὸ ⟨µὴ⟩ τὴν αὐτὴν φύσιν ὅτι οὐ τῶν αὐτῶν δεῖ ἐπιτηδευµάτων τυγχάνειν πάνυ ἀνδρείως τε καὶ ἐριστικῶς κατὰ τὸ ὄνοµα διώκοµεν, ἐπεσκεψάµεθα δὲ οὐδ' ὁπῃοῦν τί εἶδος τὸ τῆς ἑτέρας τε καὶ τῆς αὐτῆς φύσεως, 454b4–6).” Here, one of the key themes of the Republic comes to the fore: while previously the interlocutors “chased after the names” (κατὰ τὸ ὄνοµα διώκοµεν), i.e. relied on the immutability of the meaning of “nature” in relation to “sameness” and “difference”, now a redefinition of physis and the sense of the different and the identical in general seems to be taking place.

Next Socrates asks, whether the nature of the bald and the hirsute is the same or the opposite (ἐναντία); if it is opposite, can both groups be cobblers (454с1–5)? This provokes, without fail, Glaucon’s expletive γελοῖον. It is at this exact point that the passage about “doctor and doctor” follows (454c7–d3): “Would it be ridiculous for any other reason than that we did not then set up the same and different nature in all and every way, but were watching solely for that eidos of otherness and likeness which tends to the same pursuits? We meant to say, for example, that a man capable of healing and a woman capable of healing psychically have the same nature? (οὐ πάντως τὴν αὐτὴν καὶ τὴν ἑτέραν φύσιν ἐτιθέµεθα, ἀλλ' ἐκεῖνο τὸ εἶδος τῆς ἀλλοιώσεώς τε καὶ ὁµοιώσεως µόνον ἐφυλάττοµεν τὸ πρὸς αὐτὰ τεῖνον τὰ ἐπιτηδεύµατα; οἷον ἰατρικὸν µὲν καὶ ἰατρικὴν τὴν ψυχὴν ὄντα τὴν αὐτὴν φύσιν ἔχειν ἐλέγοµεν· ἢ οὐκ οἴει;)”

If we acknowledge ἰατρικὴν τὴν ψυχὴν, then ἐλέγοµεν would refer here to what has been discussed immediately before, in the sense of ‘we meant to say, implied’, since no female doctors had been mentioned anywhere above in the dialogue8. Immediately after this, it is stated that a doctor and a carpenter have different natures (454d5), and next the question is raised whether the difference between woman and man—that the female bears and the male mounts—entails the difference between them in matters of the polis (454d7–e4)?

Thus, we are presented with two distinct arrangements of the different and the identical: in one, these opposites pertain to the physical nature, in the other, to the social one. The bald is opposed to the hirsute by his physical nature, but they may be identical through their social role (e.g., if both are cobblers). A man doctor is other than a man carpenter, but they are identical by belonging to the masculine gender. A male and a female differ in what concerns physical procreation, but persons of either sex capable of healing are identical via their aptitude for studies.

Further on Socrates elaborates the topic of aptitudes pertaining to both men and women. It is here that we find the direct statement that one woman by nature is apt at medicine and another not (γυνὴ ἰατρική, ἡ δ' οὔ); one woman is apt at musical arts and another unmusical; one is apt at gymnastic and another no lover of gymnastic; one person is a lover of wisdom, and another a hater of wisdom (φιλόσοφός τε καὶ µισόσοφος),—all of this, despite alternating feminine and masculine flexions, pertains equally to both women and men (455e6–456a5).

We are shown here the dialectics of identity and difference in relation to physical and social natures. By physical nature, women are identical to women, as well as men to men, and at the same time both are different in relation to the opposite gender. However, like aptitudes make men and women identical on the intellectual and social level, while different aptitudes would bring on difference between woman and woman, as well as between man and man, within their own respective gender.

Thus, this is an instance of a complex interaction between the identical and the different, as between the two opposite natures. What really matters here is the denial of any kind of essentialism, whether natural or social: neither physis nor nomos as such can be considered to be a firm foundation for polis , which somehow resonates with the conversation between Socrates and Callicles in the Gorgias (509–511). Here, we find the physis gradually and at first barely appreciably for the reader shifting registers, moving from the horatic to the noetic level, at which prevails the aptitude to work with eide rather than with words (cf. “the chase after the names” above). While chasing after the word “nature”, the interlocutors failed to realize that this physis may well be different in relation to itself. The configuration of the two pairs of opposites (differing natures and identity vs. difference) we find in the Republic is at the same time fairly close to what will later, in the Sophistes , be shown on the example of interaction between the pairs “rest vs. movement” and “same vs. other”.

The passage about “doctor and doctor in soul ” fits into this philosophical context only if we consider these “doctors” opposites in the physical sense and correlatives socially. From this perspective, it makes sense to read ἰατρικὸν µὲν καὶ ἰατρικὴν τὴν ψυχὴν as the correlation of the different (male and female) within the identical (aptitude for healing).

Cod. Parisinus Graecus 1807. 50v

^ R. 454d

Список литературы Вчитывая женщину ("Государство" 454d)

- Adam, J., ed. (1902) The Republic of Plato. Vol. 1. Cambridge: University Press.

- Ast, Fr., ed. (1822) Platonis quae exstant opera. Vol. 4. Lipsiae: in Libraria Weidmannia.

- Bekker, I., ed. (1826) Platonis scripta Graece omnia. Vol. 6. Londini: A.J. Valpy.

- Bloom, A., tr. (1991) The Republic of Plato, 2nd ed. Basic Books.

- Boter, G.J. (1989) The Textual Tradition of Plato’s Republic. Leiden, etc.: Brill.

- Burnet, J. (1905) Platonis opera. Vol. 4. Oxonii: e Typographeo Clarendoniano.

- Chambry, E., tr. (1932) Platon, Oeuvres complètes. Vol. 7.1. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Hermann, C.F., ed. (1852) Platonis dialogi. Vol. 4.1. Lipsiae: sumptibus et typis B.G. Teubneri.

- Jowett. B. and Campbell, L., eds. (1894) Plato’s Republic. 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Grube, G.M.A. and Reeve, C.D.C., trs. (1997) Republic, in J.M. Cooper and D.S. Hutchinson (eds.) Plato, Complete Works. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 971-1223.

- King, Helen (1998) Hippocrates’ Woman. London; New York: Routledge.

- Pomeroy, S.B. (1978) "Plato and the Female Physician (Republic 454d2)", American Journal of Philology 99, 496-500.

- Schneider, C.E.C., ed. (1831) Platonis opera Graece. Vol. 2. Lipsiae: sumptibus B.G. Teubneri et F. Claudii.

- Shorey, P., tr. (1930) Plato’s Republic. Vol. 1. London; Cambridge, Mass.

- Slings, S.R. (2005) Critical Notes on Plato’s Politeia, edited by Gerard Boter and Jan Van Ophuijsen. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

- Stallbaum, G., ed. (1858) Platonis opera omnia. Editio nova.Vol. 3.1. Gothae et Erfordiae: sumptibus Guil. Hennings.

- Stephanus, H. (1578) Platonis opera quae exstant omnia. [Geneva]: excudebat Henr. Stephanus.