A house model from Popudnya, Cucuteni-Tripolye culture, Ukraine: a new interpretation

Автор: Palaguta I.V., Starkova E.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145299

IDR: 145145299 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.1.083-092

Текст статьи A house model from Popudnya, Cucuteni-Tripolye culture, Ukraine: a new interpretation

The materials of any archaeological culture include artifacts that most explicitly manifest important aspects of the spiritual life of its carriers, hidden from us by time. Despite the fact that such finds are mentioned in numerous publications, scholars return to them time and again both to analyze them from new viewpoints and to reconsider the previous interpretations.

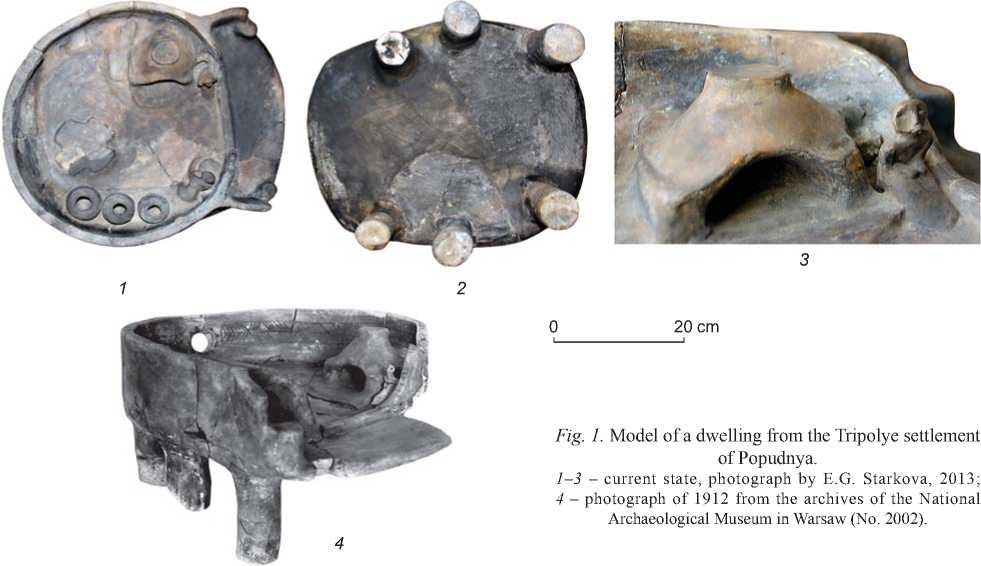

One of such objects originating in the Tripolye culture, which evolved in the south of Eastern Europe for over a millennium from the late 5th until the early 3rd millennium BC, is the model of a dwelling. This object was found in 1911 at a settlement near the village of Popudnya of Lipovetsky Uyezd of the Kiev Governorate, now Monastyrishchensky District of Cherkasy Region, Ukraine (Fig. 1). This object has been the basis for various interpretations of early agricultural portable art; however,

a number of details and the established circle of parallels make it possible to take a fresh look at this unique work of art of prehistoric Europe.

The Model from Popudnya: discovery and reconstructions

The excavations at the settlement of Popudnya were headed by M. Himner, a young employee of the Prehistoric Museum of the Warsaw Scientific Society, on behalf of Prof. E. Majewski, a member of the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society, who could not participate in the excavations due to poor health (Majewski, 1913a: 226). Thirty five dwellings, arranged in a circle, were discovered at the site covering an area of about 15 hectares; 23 dwellings were excavated (Videiko, 2004: 430). In the system of modern periodization, this settlement belongs to the Tripolye CI period, more precisely, to the first phase of the Tomashovka-Sushkovka local chronological group of sites in the Dnieper-Bug interfluve (Kruts, Ryzhov, 1985).

This clay model of a dwelling stands out from among numerous finds of pottery fragments and several dozen intact vessels, as well as anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines. The model was first published by Majewski in 1913 shortly after its discovery (1913a–c) and was described in detail by M. Himner, who at that time was a student at the Sorbonne in Paris, in his graduation thesis. Himner died in 1916 in the First World War. Seventeen years later, his thesis was published in the Warsaw Journal Swiatowit and to this date it is the most complete publication of the materials from this site (Himner, 1933). The unique find from Popudnya—the model of a dwelling—had a dramatic destiny. During the Second World War, it was brought to Germany from the destroyed city of Warsaw, then it was returned in 1947, and is now kept in the National Archaeological Museum. It is known that Majewski considered the model from Popudnya an extremely valuable object and fearing for its safety commissioned in 1913 an exact copy from the sculptor S. Roel, which was then exhibited in an exposition (Krajewska, 2009). After the death of Majewski, his wife gave both the original and the copy as a gift to the Prehistoric Museum of the Warsaw Scientific Society, which in 1945 was integrated with the National Archaeological Museum. According to the testimony of the Museum employee M. Krajewska, who alluded to the words of S. Salacinski, the Head of the Neolithic Department, only the original has survived until the present day; it is unknown what happened to the copy (Ibid.: 40). Unfortunately, the original model was heavily damaged during a fire in the collections of the Warsaw Archaeological Museum in 1991, and was subjected to significant restoration. As a result, only the base remained from the original model, and the interior was almost completely replaced, except for one surviving vessel (Fig. 1, 1–3).

Scholars have proposed various interpretations of the model, but all of the interpretations were based on the first publications and relied on black-and-white photographs taken by Majewski. In 2013, the present

Fig. 1. Model of a dwelling from the Tripolye settlement of Popudnya.

1 – 3 – current state, photograph by E.G. Starkova, 2013;

4 – photograph of 1912 from the archives of the National Archaeological Museum in Warsaw (No. 2002).

20 cm

authors had the opportunity to examine, photograph, and make a detailed description of the Popudnya find using the archival photographs from the collection of the Warsaw Archaeological Museum.

The model of the dwelling was discovered in Popudnya in 57 fragments, and the process of its reconstruction was published by Majewski (1913c). This is the largest model found throughout the entire history of research into Tripolye-Cucuteni. Its base is an oval clay platform with rims, which rests on six leg-posts. A small addition is located at the entrance, which is bound on two sides by projections of the walls flattened on top. The size of the platform is 40.5 × 36.0 cm; the total height of the model is 19 cm; the height of the rim is 9 cm; the height of the legs is 10 cm and their diameter is 4.5–5.0 cm. The thickness of the rim ranges from 0.8 to 1.3 cm. The interior surface of the walls was painted with dark brown or black paint, and a series of parallel lines was made on top of the rim (Fig. 1, 4 ).

In the black-and-white photographs published by Majewski, the model is shown from two angles: from the top and from the sides. A part of the frontal part and two legs are missing. We may learn about the decoration on the interior surface of the walls only from the descriptions (Majewski, 1913a: 231; Himner, 1933: 152), since it is almost invisible in the photographs. Only a series of cuts can be clearly seen on the top of the rim. Himner wrote that the ornamental decoration resembled woven willow branches, and the window was framed by a pattern of triangular notches on the inside and the outside. Majewski only mentioned in passing the pattern in the form of a fence on the interior surface of the walls. T.S. Passek (1938: 236) later referred to the description of Himner. Thus, the authors only mentioned that the pattern on the interior surface of the rim resembled the representation of wicker weaving. However, two studies of Passek contained a drawing of the model from Popudnya where the ornamental decoration was rendered as a series of diamond shapes (1941: 219, fig. 10; 1949: 95, fig. 5, 4 ). This drawing was not made by the author: the caption under the drawing in the article of 1941 indicated “after Buttler-Haberey” (in the study of 1949, the same drawing was reproduced without this reference). This caption refers to the book by W. Buttler and W. Haberey on the settlement of the Köln-Lindenthal Linear Pottery culture, where a photograph of the model from Popudnya clearly showed an ornamental pattern on the upper third of the rim, and triangular cogs filled with black paint, which framed the window (Buttler, Haberey, 1936: Taf. 32). The same pattern on the rim can be seen in the archival photographs of the model in the process of its restoration (Fig. 1, 4 ). Thus, it is possible to agree with Himner and Passek that the ornamental decoration on the rim imitated the wicker weaving from which the frame of the wall was made.

The interior of the dwelling contains a stove to the right of the entrance, a cross-shaped elevation measuring 9.5 × 9.2 cm in the center, and three large pear-shaped vessels, attached to an elevation 0.5–0.6 cm in height, which runs along the left wall. The height of the vessels ranges from 3.5 to 4.5 cm; the diameter of their necks is 1.8–1.9 cm. Two of them have several deep parallel incisions in their upper part.

The stove is square in plan with walls 9.6 cm long; it is a domed structure with a flattened rounded top. Two small rounded protrusions were made outside of the stove opening; these protrusions have not been reproduced in the latest restoration of the model. A step is adjacent to the left wall of the stove, which was interpreted as a bench (Passek, 1938: 237). There is also a protrusion at the right wall, but it is small, of subsquare shape and resembles a seat. A low pedestal on which the stove together with the “bench” and “seat” are located, looks similar to the crossshaped elevation in the center of the dwelling.

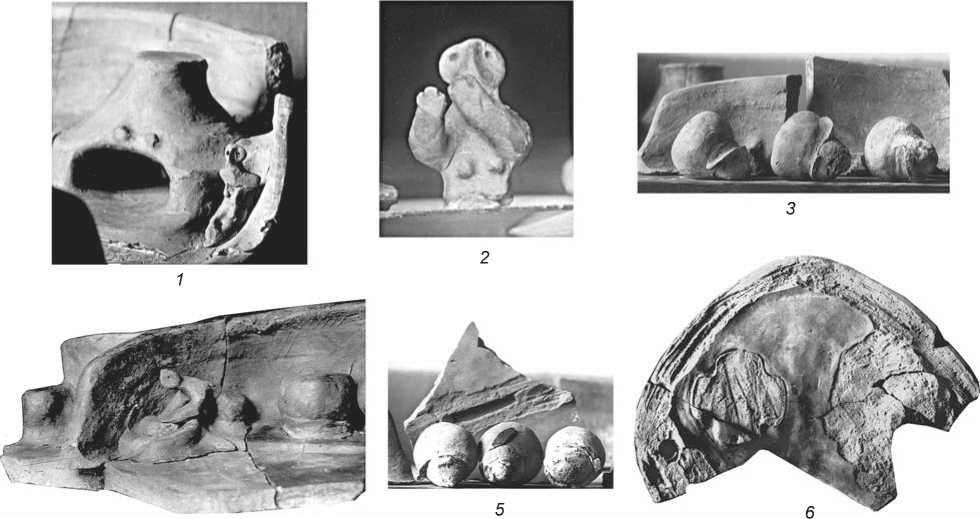

A seated anthropomorphic figurine was placed to the right of the entrance, between the stove and the wall. It does not show sexual features; the head was made with three pinches; the eyes are marked with rounded through punctures, which is typical of the Tripolye figurines of the middle and late periods. The posture of the figurine is of particular interest: it is a sitting figure with crossed arms on the chest and crossed legs (Fig. 2, 1 ). A note on the position of the legs can be found in the study of Majewski, but he did not comment on it in any way (1913a: 235). Parallels to this posture have not been found among the statuary of the Tripolye-Cucuteni.

The gaze of the figure sitting by the stove is directed at another human figurine kneeling to the left of the entrance (Fig. 2, 4 ). Its head is also made with three pinches, and the eyes are rendered with through punctures. The palms with fingers are outlined, which is a rare feature in the traditional Tripolye figurines*. This is clearly the image of a woman: although the posture makes it difficult to determine the gender of the figure, one of the archival photographs taken during the restoration process shows the figurine separately with breasts clearly indicated (Fig. 2, 2 ). The character is holding the upper stone of a hand-mill located in a special “trough”, fashioned from clay bolsters.

Thanks to the archival photos, we have some idea about the specific features of the manufacturing technique of the model. In the process of its modeling, the craftsman had to solve far more complex technical problems than the problems occurring in forming pottery vessels. In order to prevent subsequent deformation, the plate that served as the base of the model had been previously

Fig. 2 . Fragments of the model before gluing, photograph of 1912 from the archives of the National Archaeological Museum in Warsaw.

1 – anthropomorphic figurine and stove to the right of the entrance (No. 2042); 2 – upper part of the female figurine (No. 2041); 3 – vessels from the interior (No. 2038); 4 – female figurine to the left of the entrance (No. 2030); 5 – vessels from the interior and a fragment of the “entryway” with a groove for attaching the threshold (No. 2039); 6 – platform fragment of the model (No. 2042).

slightly dried. Its surface was intentionally left rough for ensuring a tight connection during the subsequent assemblage (Fig. 2, 6 ). A vertical rim was attached to this flat platform, yet without further strengthening of the joint with a ribbon of clay, as was often done in molding large vessels. That is why the structure was later split along the seam. The threshold between the “entryway” and the main room was fashioned after the clay of the rim and the platforms had already dried a bit. Therefore, a special groove was made in advance in the floor for strengthening the threshold (Fig. 2, 5 ).

All interior details (the stove, the “bench”, the “seat”, and the low podium), as well as the human figurines, had been made separately, and were successively mounted on the floor of the dwelling. The vessels did not simply stand on the podium; they were inserted into specially made recesses. A spiral band of clay was added at the junction of the vessels and the podium (Fig. 2, 3 , 5 ). This band of clay is too bulky for serving as additional strengthening, for which there was no need. It rather served as an imitation of special ledges for holding large vessels, which are sometimes found in the dwellings at the settlements of the Tomashovka-Sushkovka group of sites (Chernovol, 2013: 82). After assembling, the entire model except for the figurines and vessels was covered with a thick layer of liquid clay for smoothening the surface and additional strengthening of the details.

Majewski believed that the model represented “a fence on posts”, where the rounded opening served for visibility and garbage disposal, and a cross-shaped open hearth was located in the center. According to Majewski, the dwelling itself was located to the right of the entrance; there are two projections for fastening the curtains at the entrance of the dwelling. Majewski claimed that due to its small size this hut could only have been used as a shelter, while the main life of the inhabitants took place within the fence, and referred to similar dwellings of rounded shapes, which were represented in ancient Egyptian bas-reliefs (1913a: 233). He interpreted the representations of the seated man and the woman grinding grain as an everyday scene (Ibid.: 235). H. Cehak had a similar opinion; she noted that the sizes of the model, the figurines, and the details of the interior were proportional and made it possible to determine the size of the real dwelling (1933: 207).

Himner also interpreted the model as an open terrace with a hut, surrounded by walls. However, he believed that the figurine at the stove was also female, because in his opinion male figures should have had only one eye (Himner, 1933: 151–154). Unfortunately, he did not provide any parallels to the one-eyed representations of males; most likely, he meant those Tripolye male figurines that really had only one eye (see, e.g.,

(Monah, 1997: Fig. 200, 4 , 210, 6 , 7 , 211, 7 )). Himner also believed that the rounded window surrounded by triangular cogs had some sacred meaning and was used not for visibility, but rather to catch the ray of the sun as through the holes in the menhirs (Himner, 1933: 154–155).

A radically different interpretation of the model from Popudnya was proposed by Passek in her studies (1938, 1941, 1949: 95–96). She rejected the suggestion of Majewski and Himner that this was “a fence on posts”, and interpreted the object as a model of a dwelling with the interior space. Passek correctly interpreted the part that had been formerly called the hut-shelter, as the stove. Passek paid particular attention to the purpose of the figurines and the cross-shaped elevation in the center of the platform. According to her, the figurine to the left of the entrance was a realistic representation of a kneeling woman grinding grain on a milling stone, and the figure to the left of the stove was a cultic female idol, as confirmed by a quote from the study of Himner, where the figurine was called the “idole féminine” (Passek, 1941: 218–219; Himner, 1933: 152). However, wherever Himner wrote about the figurines, he used the term “idole” (1933: 100, 102); he obviously did not distinguish between the notions of “small statue” and “idol”, and did not imply any special difference in the meaning. However, Passek claimed that “the presence of two different categories of female representations in the model once again emphasizes the cultic significance of the Tripolye idol, which was placed in the central part of the home near the hearth” (1941: 219). She also saw a direct connection between the “idols” in the models of dwellings and Late Tripolye schematic figurines from Serezlievka, Usatovo, and Krasnogorka, found in burial mounds (Ibid.). This authoritative interpretation of the person near the stove as an “anthropomorphic idol” became firmly established in the literature (Chernysh, Masson, 1982: 248).

If we examine the model, the cross-shaped elevation in its central part, the edges of which were incised with a series of short parallel cuts, is of particular interest. Majewski and Himner believed that it was an open hearth (Majewski, 1913b: 78; Himner, 1933: 152), but later V.E. Kozlovska and T.S. Passek interpreted the crossshaped elevation as an altar (Kozlovska, 1926: 43; Passek, 1938: 241; 1941: 214).

Details of the interior that are similar to those shown on the model from Popudnya, widely occur among the materials found in the excavations of dwellings at Tripolye-Cucuteni. Thus, cross-shaped elevations have been discovered in at least five dwellings in the settlement of Vladimirovka (Passek, 1949: 83–85). The edges of one of them were decorated with small notches, like on the model from Popudnya (Passek, 1941: 214; Passek, 1949: 83). Judging by the description, some of the cross- shaped podiums had four circles of regular shapes in relief with grooves. The published photograph shows that the “cross” is actually formed by four semicircles (Passek, 1949: 89, fig. 40, 44). Rounded depressions at the edges of the “cross” also occur in the model from the settlement of Cherkasov Sad II (Polishchuk, 1989: 47, fig. 16, 9). In the later settlement of Talyanki, the décor of four circles is located on elevations of rounded shape (Chernovol, 2008: 174–175, fig. 10).

Passek also pointed out that in one case a crossshaped elevation with a diameter of 2 × 2 m and a height of about 35 cm was built on a flat rounded earthen base, while in another case, two cross-shaped podiums were found in the same building (1941: 214). Such “altars” in the dwellings might have been located both in the central part of the house and in the entryway (Passek, 1938: 240). A similar cross-shaped structure was also found a dwelling at the settlement of Poduri in Romania, in the layer associated with the period Cucuteni B1–Tripolye BII, but it had only one rounded recess with traces of fire in the center (Dumitroaia et al., 2009: 19–21, 43). The Tripolye settlements of that time also had stoves on cross-shaped pedestals; for example, such structures were found by V.I. Markevich (1981: 86) in Brinzeni III.

Clay elevations in dwellings have been often found in the settlements of the initial Late Tripolye culture, but in most cases they are of subsquare or rounded shape. Many scholars called such elevations altars (Issledovaniye…, 2005: 58, fig. 37; Kruts, Korvin-Piotrovsky, Ryzhov, 2001: 24–25; Shmagly, Videiko, 2003: 88; Tripolskoye poseleniye-gigant…, 2013: 17, fig. 5). Markevich, who published the materials from the Late Tripolye sites of the Northern Moldova, regarded them as places for grinding grain (1981: 36–37, fig. 45).

The representation of the podium for large vessels on the model also corresponds to archaeological finds. Such podiums were typical for the dwellings of the Tomashovka-Sushkovka local group of sites. As a rule, they were also located to the left of the entrance (Chernovol, 2013: 79). An interesting point was noted by T.G. Movsha during the excavation of a clay platform at the settlement of Dobrovody. Having analyzed the composition of clay of the podium and of the vessels themselves, Movsha came to the conclusion that they had been made of the same clay compound and were most likely molded together (1984: 19).

Thus, the model from Popudnya virtually completely reproduces the interior space of the dwellings from the settlements of the Tomashovka-Sushkovka group such as Talyanki, Maidanetskoye, Dobrovody, and others. The interior space there was “distinguished by extreme uniformity” (Chernovol, 2008: 176). The stove was always located to the right of the entrance; the podium with large vessels was located to the left of the entrance, and the clay elevation (“the altar”) was located in the center opposite to the entrance, close to the opposite wall (Kruts, 1990: 45; Kruts, Korvin-Piotrovsky, Ryzhov, 2001: 66–74; Issledovaniye…, 2005: 9–10, 57–59; Shmagly, Videiko, 2003: 88).

Models of dwellings and the associated characters: circle of parallels and cultural context

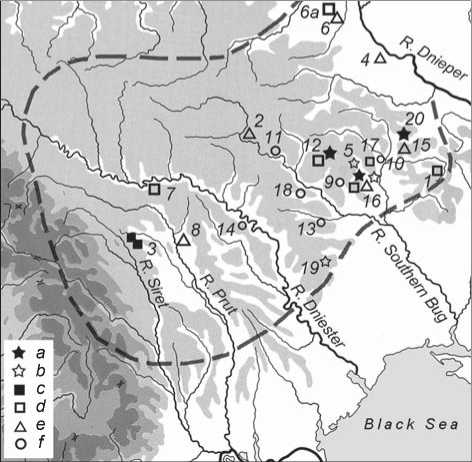

Up to date, over sixty models of dwellings have been found on the territory of the Tripolye area; about a third of them are chronologically close to the Popudnya model and are associated with the Tripolye CI period (Fig. 3). Problems of typology and classification of these artifacts have been already discussed in the literature (Movsha, 1964; Ovchinnikov, 1997; Gusev, 1996; Yakubenko, 1999). In terms of external appearance, all authors distinguish between open models (without a roof) and closed models (with a roof), with interior details and without them. The configuration of the platform is also taken into consideration in the most

Fig. 3 . Settlements of the Tripolye culture of the Middle–Initial Late Periods (BII–CI, CI) where the models of dwellings have been found.

1 – Vladimirovka; 2 – Voroshilovka; 3 – Geleeshti; 4 – Grebeni;

5 – Dobrovody; 6 – Kolomiyshchina II; 6a – Kolomiyshchina I; 7 – Konovka; 8 – Kosteshty IV; 9 – Kocherzhintsy; 10 – Maidanetskoye;

11 – Nemirov; 12 – Popudnya; 13 – Pishchana; 14 – Rakovets; 15 – Rassokhovatka; 16 – Sushkovka; 17 – Talyanki; 18 – Trostyanchik;

19 – Cherkasov Sad II; 20 – Chichirkozovka.

a – d – open models: a – with interior details and characters; b – with interior details; c – with characters; d – without interior details; e – closed models; f – fragments of objects whose type cannot be established.

detailed classification by S.A. Gusev (1996). According to that classification, the model from Popudnya belongs to type BI1—open, of rounded shape and with interior details (Ibid.: 18, 28). This type also includes objects originating from the same group of sites of the “Tomashovka type”, such as the giant settlement of Talyanki (Kruts, 2008), Dobrovody (Movsha, 1984; Shatilo, 2005), and a miniature simplified model from Sushkovka in the form of a small bowl on legs, where the only interior detail depicted is the stove (Kozlovska, 1926: 56–57, fig. 3). The form of the object from Cherkasov Sad II (Kodymsky District of Odessa Region, Ukraine) is also simplified. Only the recess in the frontal part and cross-shaped “altar” in the center indicate that this is the model of a dwelling. Because of the “altar”, this find was interpreted as a representation of a cultic structure (Polishchuk, 1989: 48). “Open” models without interior details constitute a wider range of similar objects. Along with “closed” models, they occur at the settlements of Tripolye-Cucuteni of various periods*.

Models of the open type with interior details, where human figurines of the same scale were placed, similar to the Popudnya model, should be singled out as a special type of objects. The closest parallel is the model from the settlement of Sushkovka (Umansky District, Cherkasy Region, Ukraine). This model contains all the same elements of the interior except for a human figurine near the stove (Kozlovska, 1926: 52–53, fig. 1, 2; Passek, 1949: 125). This figurine might have been placed separately into the interior space: a whole series of seated figurines, some of which might well have been used in the models of dwellings, go back to the period of Tripolye CI–Cucuteni B (see (Monah, 1997: Fig. 176–183)). This type of object also includes a fragment of the model from Chichirkozovka (Zvenigorodsky District of Cherkasy Region, Ukraine), which preserved a spot near the stove where a human figurine sitting next to the stove used to be attached (Passek, 1941: 219, fig. 11; 1949: 125, fig. 69, 3 ). These three examples reflect a stable association of dwellings with characters placed inside.

The practice of exhibiting figurines in the interiors of dwelling models—a sort of “doll house”—was sufficiently widespread in the cultures of the Balkan-Carpathian circle (Palaguta, 2012: 91–94, 98). Models of dwellings with figurines placed inside have been found at the settlement of Ghelaie^ti in Romania, which dates back to the end of the Cucuteni A-B–early Cucuteni B period. One model contained four figurines; another model contained two. Figurines were both male and female (Cuco$, 1993). Four figurines along with interior details were placed inside the model of a dwelling from the complex of Ovcharovo in Bulgaria (Todorova, 1983). Eight figurines of various gender and sizes were placed into a model, which reproduced the proportions and interior of the house where the model was found under the floor in Platia Magoula Zarkou in Greece. The author of the excavations interpreted the figurines as representations of three generations of the same family (Gallis, 1985). “Altars” on legs, resembling the models of dwellings, might have been specifically designed as a container for exhibiting figurines. Such an “altar” in the form of a bowl with a diameter of 42–43 cm on legs was found, for example, at the pre-Cucuteni–early Tripolye settlement in Isaia next to a vessel containing a set of figurines (Ursulescu, Tencariu, 2006: 123; Palaguta, 2013: 148, fig. 1, 2 ; 8, 2 ). Such sets allowed for free placement of figurines in the process of forming the composition, and manipulating with them. In most cases, the scale of the figurines was larger than the scale of the model of dwelling, as it is often the case with modern children’s toys (Palaguta, 2012: 93–94).

The semantic field of this group of early agricultural portable art, constituted by a stable association of the characters and the dwelling, intersects with the cult of the household gods of Antiquity (Lares and Penates), which, in turn, were associated with the cult of the ancestors according to the written sources and the pictorial tradition (Palaguta, Mitina, 2014). The assumptions about the direct relationship of these examples of portable art with the cult of the ancestors are based either on the parallels between the models of dwellings from the Neolithic and the Chalcolithic and funerary urns in the form of “houses of the dead” of the Bronze and Early Iron Age (Gladilin, 2009), or on folklore parallels (Dyachenko, Chernovol, 2007).

However, it seems that the models from Popudnya, Sushkovka, and Chichirkozovka reflect a certain independent phenomenon. The figurines there were not only executed in the scale of the interior space of a typical Tripolye dwelling, which enhanced the realism of the scene, but also were represented in the process of performing a certain action: one person (the female) is grinding grain on a milling stone, and another person (probably a male) is sitting by the stove and watching her (the gender roles are reflected clearly and vividly). This scene is most fully represented in the model from Popudnya, but we may assume that the same “everyday” subject was the basis of sculptural compositions in the interior of the models from Sushkovka and Chichirkozovka. They differ from other similar objects with figurines in the correlation of the scale of figurines and the house, as well as in the attachment of the figurines: they were not supposed to be moved or removed from the model, which points to the intended representation of a specific scene. The repetition of this scene on several objects indicates that the image acts as illustration of a specific text, possibly, a folklore or heroic subject, which for several generations was regularly cited in the comments on this sculptural composition within a specific group of the Tripolye-Cucuteni population.

The settlements where the models of the Popudnya type were discovered are geographically and chronologically close to each other. All of them belong to the Tomashovka-Sushkovka group of sites left by the population that moved to the forest-steppe belt of the Dnieper-Bug interfluve from the Dniester area in the Tripolye BII–CI period (Kruts, Ryzhov, 1985: 53–54). The carriers of this tradition created giant settlements, whose area reached 300–400 ha and the number of dwellings reached 2000. According to various estimates, from 4000–5000 to 10,000 people lived in each of these settlements. The three-dimensional “narrative” representations are combined there with a concentration of discoveries not only of dwelling models, but also of sleigh models (Balabina, 2004). The emphasis on a subject associated with movement of goods was triggered both by the need to supply the sprawling settlements and by the established practice of “nomadic agriculture”, which caused periodic moving of settlements to a new location after 50–60 years.

In addition, most of the “realistic” anthropomorphic figurines were discovered within the Tomashovka-Sushkovka group of sites (Burdo, 2010: Map 1; 2013). The term “realistic figurines”, which was introduced by Movsha (1975), is not quite acceptable from the viewpoint of current art history where “realism” primarily means a creative method aimed at reflecting the surrounding reality in artwork and is mostly applied to the content of the artwork (Shekhter, 2011: 11–14)*. The notion of “naturalism” is more suitable for the Tripolye-Cucuteni art, since naturalism was necessary to create a similarity aimed at recognition (Ibid.: 14).

The emergence of a sufficiently representative series of naturalistic representations in the Tripolye BII–CI period could have been caused by the need to give a specific expression to the characters depicted against the background of changes in the social reality—the formation of collectives of considerable sizes, which comprised the population of giant settlements (Palaguta, 2012: 242–246). Communities amounting to a thousand people and consisting of a number of clans and families had the need to render individual traits of the characters represented. In this way they became more easily recognizable not only within the families living in individual households or within the groups of buildings, but also by their more distant neighbors.

Conclusions: on the interpretation of the models of dwellings

All of the above makes it possible to address the problem of the function of the models of dwellings. Obviously, it cannot be solved following the tendency that dominated until recently, to correlate the portable art of European early agricultural cultures exclusively with fertility cults. This approach, embodied in the fundamental studies of M. Gimbutas (1996), seems to be one-sided and speculative, lacking a clear substantiation in specific materials. It is also clear that the models of dwellings were represented both in the Tripolye culture and in other cultures not as “temples”*, but as “typical” dwellings.

The tradition of making models of dwellings was widespread in the cultures of the Balkan-Carpathian circle. Such finds are relatively common, and they should be viewed not as a special phenomenon, but as a part of the entire portable art complex. These objects have a polysemantic value that may vary within specific cultural traditions and may change in the process of development.

Most certainly, the model from Popudnya represents not a simple everyday scene as Majewski once thought (1913a: 227, 235). This cannot be the case since the same scene is reproduced on similar objects from Sushkovka and Chichirkozovka belonging to the same Tomashovka-Sushkovka group of sites. The sculptural composition could be associated with a specific folklore or mythological subject widespread among the carriers of the Tripolye-Cucuteni traditions, which had to be rendered using naturalistic forms of representation. It is also possible that these models were intended to visually express an auspicious formula associated with the foundation of the household or settlement, or with the cult of the ancestors—the founders of the family clan.

Acknowledgements

We express our deep gratitude to Dr. B. Brzezinski, the Director of the National Archaeological Museum in Warsaw, S. Salacinski, the Head of the Neolithic Department, and M. Krajewska, the employee of the Department of Scientific Documentation, for the opportunity to explore and publish the model of the dwelling from the Tripolye settlement in Popudnya using archival photographs. We are also very grateful to Dr. hab. A. Zakoscielna from the Institute of Archaeology at the Maria Curie - Sklodowska University in Lublin for his assistance in the work with archival documents.