A Mongolian era female headdress from the Upper Ob basin

Автор: Pozdnyakov D.V., Orozbekova Z., Shvets O.L., Ponedelchenko L.O., Marchenko Z.V., Grishin A.E., Pilipenko S.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145402

IDR: 145145402 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.4.074-082

Текст обзорной статьи A Mongolian era female headdress from the Upper Ob basin

Mongolian era female headdresses of the bocca type* have been found quite rarely in Western Siberian archaeological sites. The number of such items found in the Volga basin is comparatively great, despite the perishable material used in their manufacture. The area of dispersal of the bocca headdress is quite large, owing to the strong Mongolian influence on the populations of the vast Eurasian territory in the 13th to 14th centuries (Myskov, 2015: 195–196). Several types of bocca headdress have been recorded (Pilipenko, 2007; Tishkin, Pilipenko, 2016). Descriptions of new finds and their typological determination are topical for the medieval archaeology of Eurasia. The discovery of

The burial containing the bocca remains belongs to a large cemetery of Krokhalevka-5, located in the northern part of the Upper Ob Basin, at the western edge of Kudryashovsky pine forest, near Novosibirsk (Sumin et al., 2013: 38–40) (Fig. 1). The majority of the Krokhalevka burial mounds have been dated to the 13th to 15th centuries; others to the Late Bronze–Early Iron Age periods (Galyamina, 1987). Almost all the mounds and medieval graves show signs of disturbance. In 2015, at the necropolis adjacent to mound 75, intact medieval burials and a contemporaneous commemorative structure were discovered (Marchenko et al., 2015). Archaeological materials from one of these burials are described in this paper.

Archaeological context

The headdress was found in intact burial 27 located close to the center of mound 75, at the northern end of a line of at least four synchronous burials. At the bottom of the grave, under a birch-bark cover, a complete skeleton of a woman 35–40 years old was found*. The body had been placed in a supine position, with her head towards the east. The arms were stretched along the body; the skull was oriented with its facial part towards the north (Fig. 2, A ).

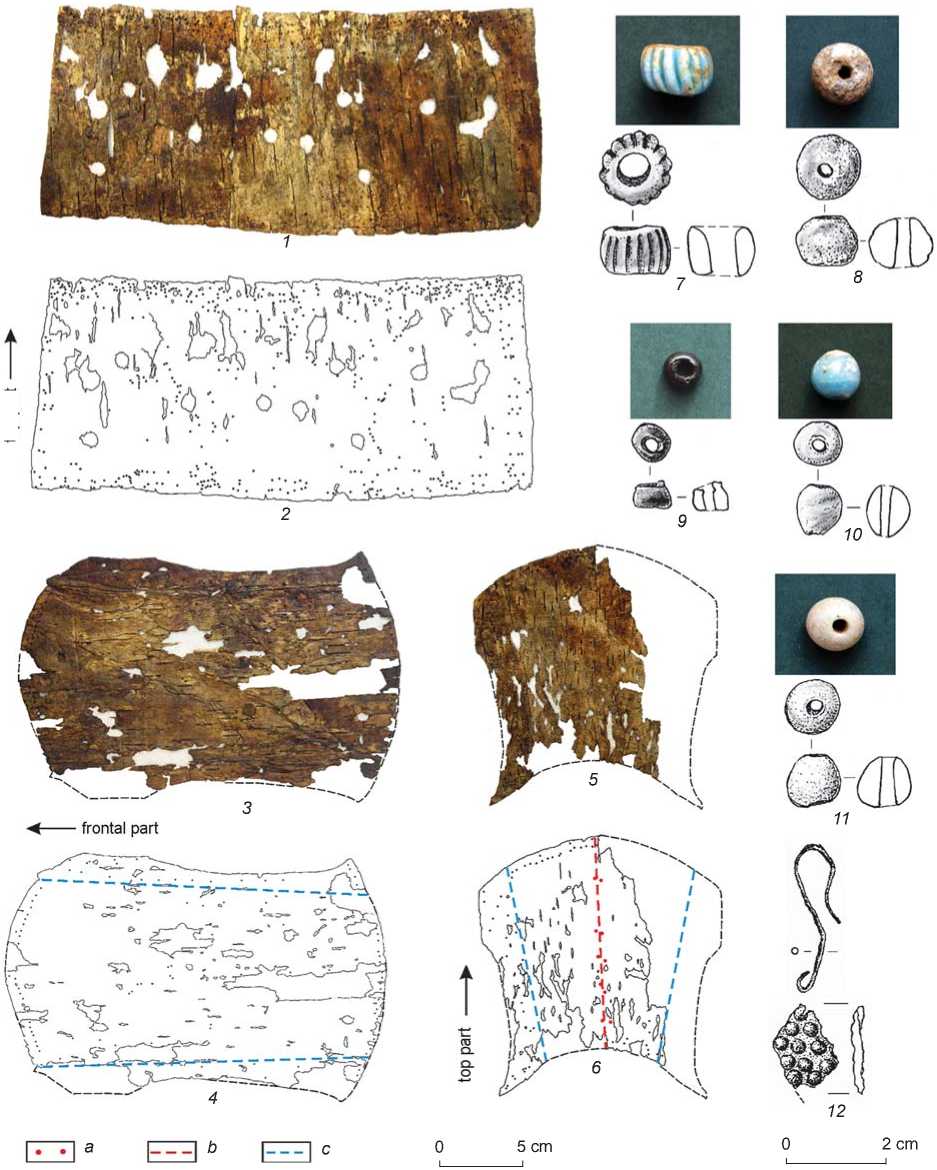

The bocca’s remains were revealed 5–6 cm apart from the parietal bone (Fig. 2, B ). The headdress had been deformed by the pressure of the overlying cover and soil; some bocca parts were found pressed into the birch-bark pieces. By the time of the cover’s sinking, the bocca already lay on the side, with its frontal part towards the north (like the front of the skull). The headdress was likely put into the grave in the position “on the head”. However, it is impossible to determine whether it was put on the head or placed separately. The state of preservation of the headdress’s parts varies from satisfactory to poor. No remains of textile trimming, nor of the wooden frame of the bocca (including the cap, to which the birch-bark frame would have been attached) were found.

Near and inside the bocca, at the skull and the upper postcranial bones, large and small beads of white, green, greenish-blue, or black opaque glass were found, which decorated the headdress** (Fig. 2, B ; 3, 7–10 ). The glass

Fig. 1. Location of the Krokhalevka-5 cemetery.

items show various states of preservation; the majority of beads are destroyed. Two beads of white stone were discovered at the joint of the upper and lower parts of the bocca (Fig. 3, 11 ). Some green glass fragments belonged to flattened ornaments (see Fig. 2, B , 11 ). Some items of this set probably ornamented the bocca as well. To the left of the skull’s base, a bronze earring in the form of a rhomboid plate, decorated with convex hemispheres all over the surface, were found (see Fig. 3, 12 ). On the breast, a black stone pendant was found (see Fig. 2, B , 16 ), which apparently was not associated with the headdress. On the body and the bones of the extremities, heavily perished fragments of ornamented silk fabric were placed.

Conservation and restoration*

As a result of synchronous works on the archaeological cleaning of the headdress’s remains and on primary field conservation, the birch-bark elements have been partially stabilized. Primary conservation was carried out with the aid of a water solution of the low-molecular PEG-400, with an admixture of Lysoformin 3000 disinfectant. This made it possible to separate headdress elements safely from the grave filling, and to recover them. Additional brush cleaning along with the preservative injections was made in the field laboratory. The elements were fixed on a hard base for temporary storage and transportation.

The following conservation and restoration procedures were carried out in the laboratory: complete removal of soil remains from the find through washing on sieves with distilled water and preservative water solution alternately; conservation and simultaneous soft spreading of fractures and deformations of all elements, with subsequent pressuring under small load; conservation process was finished with the high-molecular agent PEG-1500. After

*The works have been performed by O.L. Shvets and L.O. Ponedelchenko.

А

|

1 |

0 6 |

■ |

11 |

«а 16 |

|

2 |

о 7 |

О |

12 |

<4 17 |

|

3 |

о 8 |

о |

13 |

18 |

|

4 |

0 9 |

* 2 |

14 |

X 19 |

|

5 |

е 10 |

О |

15 |

B

Fig. 2. The burial at the level of the skeleton cleaning (the northwestern view) ( A ), remains of the bocca and ornaments on the combined photo-scheme ( B ).

1 – base outline; 2 – base seam; 3 – frontal plate outline; 4 – rear plate outline; 5 – cover outline; 6 – white glass bead; 7 – green glass bead; 8 – greenish-blue glass bead; 9 – figured greenish-blue glass bead; 10 – black glass bead; 11 – flat green glass ornament; 12 – small white glass beads; 13 – small green glass beads; 14 – deposition area of fragmented small white glass beads; 15 – white stone bead; 16 – black stone pendant; 17 – bronze earring; 18 – outlines of the decoration inside or below the bocca; 19 – poorly preserved item.

drying at room temperature and humidity, the original shape of the elements assembled on a board was restored using natural gauze and LASCAUX Acrylkleber 360 HV glue. The restored elements were fixed on a board. The object is now ready for display in the Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of SB RAS.

Design of the birch-bark frame of the headdress

Headdress parts were cut out with a knife from a layer of birch-bark. Holes for assembly, drapery, and decoration of the headdress were made with needles of various size. The headdress’s shape and size were ensured primarily by the bark’s rigidity. An additional framework made of small twigs, now perished, was probably used.

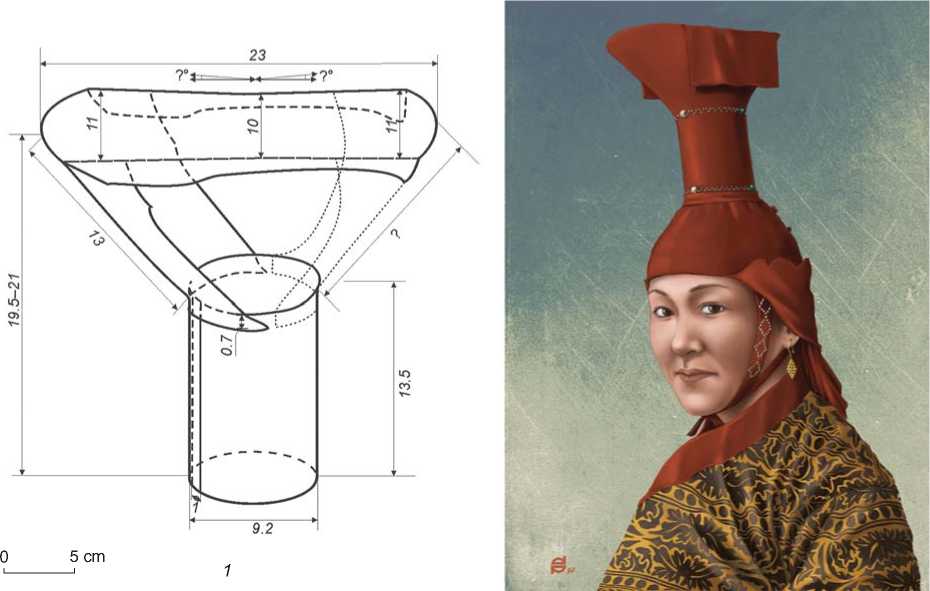

The birch-bark frame of any type of bocca consists of two parts: a cylindrical base and a top (Fig. 3, 1–6 ). The main parts of the capital-shaped top, reminiscent of a reversed truncated pyramid, are cover, frontal plate, and rear plate. The Krokhalevka headdress’s frame was comparatively well preserved, while the state of preservation of the top elements was rather poor (parameters of the rear plate can hardly be deduced).

The cylindrical base was made of a rectangular one-layer piece, and shows a good state of preservation top part

Fig. 3. Photo ( 1 , 3 , 5 ) and drawings ( 2 , 4 , 6 ) of restored elements and some pieces of the bocca decoration ( 7–12 ).

1 , 2 – base; 3 , 4 – cover; 5 , 6 – frontal plate; 7 – 11 – beads; 12 – earring ( 1–6 – birch-bark; 7–10 – glass; 11 – stone; 12 – bronze) (drawings by M.E. Medovikova). a – “framework” holes; b – frame elements; c – fold-lines of the elements.

Fig. 4. Schematic structure of the bocca’s birch-bark base ( 1 ) and its graphic reconstruction ( 2 ). Made by D.V. Pozdnyakov.

(Fig. 3, 1 , 2 ). The bark’s pattern runs perpendicular to the long axis of the piece—providing, as we believe, a greater rigidity than otherwise. The piece is 13 cm wide, in conformity with the height of the cylindrical base of the headdress (Fig. 4, 1 ). The lower edge of the piece is 31 cm long, the upper edge is 29 cm long; the difference is explainable by the shrinkage and residual tension of the bark during the headdress’s construction. The bark blank was rolled up with 1 cm overlapping, this technique being suggested by the coincidence of holes on the short sides. In this case, the original diameter of the sewn-up blank was within the range of 9.2 ± 0.3 cm. The overlapping joint was fastened with a seam. The joint was made on the bocca’s frontal part and coincided with the vertical axis of the frontal plate. Joints of this type have been recorded on similar headdresses from the cemetery of Novy Kumak (northwestern group 3) in the southwestern Urals (Bytkovsky et al., 2014: 221).

Four birch-bark fragments (see Fig. 2, 2 ) were attached to the upper edge of the base, one of which was the lower part of the frontal plate, and three other pieces were associated with the lower portion of the poorly preserved rear plate (see Fig. 4, 1 ).

The cover was well-preserved. It was made of a onelayered birch-bark plate, with the bark pattern running along the plate (see Fig. 3, 3, 4). The cover is a long rectangle in shape (23 cm long), with the short sides rounded. The width varies from 13 cm at the front to 12 cm at the rear (see Fig. 4, 1). Folds are traceable at approximately 2 cm from the long edges. The folds were used in attaching the frontal and rear top plates to the base. Thus, upon assembly of the birch-bark base, the cover became nearly rectangular in plan view, as in many other bocca headdresses (Erdenebat, 2010; Tabaldiev, 1996; Orozbekova, Akmatov, 2016).

Top plates. The frontal plate was better preserved than the rear one (see Fig. 3, 5 , 6 ; 4, 1 ). The frontal plate was made of a piece of birch-bark with a length of ca 13 cm along the vertical axis and a maximum width of ca 14 cm. The bark’s pattern runs along the long axis of the plate. The upper edge is rounded; the lower edge shows a deep semi-circular cut. Folds are traceable at ca 3 cm from the lateral edges of the frontal plate, like those on the cover. The plate’s shape is typical of the Mongolian and Tian Shan type of bocca, widespread over the region stretching from Kyrgyzstan to Mongolia (Tishkin, Pilipenko, 2016: 22).

Cuts up to 1.5 cm deep were made in the long edges of the cover and top plates, making the long sides concave. The cuts were probably made after assembling the birchbark base of the headdress, in order to facilitate access to the headdress’s interior during the subsequent drapery and decoration.

Holes and seams. Obviously, only some of the holes were designed for fastening the birch-bark elements together. These holes were made along the edges to be sewn; some of them can be matched when superimposing the elements. Some holes are located in pairs, equidistant from one another, along the longitudinal axis of the frontal plate (Fig. 3, 6 ). Most likely, such a system corresponds to a z-seam. Z-seams were commonly used by the nomads of southwestern Siberia in manufacturing funeral birch-bark items (Roslyakov, Pilipenko, 2008: 154; Grushin, Frolov, Pilipenko, 2015). Such seams were noted on boccas from Teleutsky Vzvoz-1 (the Barnaul-Biysk region of the Ob) (Tishkin, 2009) and the cemetery of Novy Kumak (the Ural-Volga basin) (Bytkovsky et al., 2014: 221). Experimental manufacturing of bocca models has shown that the z-seam securely connected birch-bark elements, and could fix wooden frame elements on them*. The holes close to the cover center were likely used for attaching the exterior wooden decoration in the form of a cross.

We were not able to determine the purposes of the other holes. These were probably used for attaching the exterior decorations, drapery, or the interior frame.

The issue of the bocca’s decoration with beads and other decorative elements requires additional study of all the finds. The proposed variant of decoration with beads of the cylindrical base, adjoining the cap, may have been similar to the items from the sites at Mayachny Bugor II, in the Volga region (Mamonova, Lantratova, Orfinskaya, 2012: 125, fig. 5). Among the headdresses of the type of bocca found in the Eurasian steppes, only one headdress (from Novy Kumak) is decorated with a large bead in the lower part of the birch-bark cylinder (Bytkovsky et al., 2014: 221, fig. 8, 1 , 5 ).

Reconstruction of the bocca’s size and appearance

The birch-bark part of the headdress is 19.5–21.0 cm high, including the cylindrical base 13 cm high, and the assumed height of the widening top of 7.5–9.0 cm (see Fig. 4, 1 ). The diameter of the cylindrical base was approximately 9.2 cm. The cover was 23 cm long and 10–11 cm wide when assembled. Judging by the available analogs among archaeological and visual-art materials, the cover of the top might have been inclined either forward or backward, owing to the difference in height of the frontal and rear plates.

On the basis of the available surviving items from other archaeological sites, and their representations,

*The experiment was carried out by S.A. Pilipenko and V.Y. Maklasov.

the bocca headdress should have been provided with an exterior textile drapery and a special cap fixing the bocca on the head*. There was a tradition of decoration of all parts of the headdress: with small feather plumes and twigs on the top, and with rhomboid symbols on the cap and laces. Unfortunately, none of these decorative elements survived on the headdress under discussion. The rhomboid motif, popular in the decoration of such objects, is represented only in the bronze pendantearring (see Fig. 2, B , 17 ; 3, 12 ). The two white beads found next to the cover can be regarded as remains of the plume base.

On the basis of the estimated size of the Krokhalevka bocca and its better-preserved analogs, a graphic reconstruction of the headdress was made (see Fig. 4, 2 )**. Modeling was based on the features of the most representative surviving variants of the headdress: red color of decorative elements, and the appearance and ornaments of the cap (see, e.g., (Erdenebat, 2010)). It is possible that there was a plume on the cover of the headdress, but there was no space for it in the grave. The plume was either deformed or taken away before placing the bocca into the grave. We did not reproduce the plume (or any other possible decorative elements) in our reconstruction, because there are many varieties of plume, and any remains of it in the burial were missing. The general shape of the headdress has been reconstructed with great probability, and the place of an ornamental rapport made of small beads is indicated (on the upper edge of the cylindrical base); though the regularity and continuity of the rapport are controversial. The lower rapport of small beads is represented according to the known analogs.

Analogs to the headdress under study

According to the classification by S.A. Pilipenko, the bocca from Krokhalevka belongs to the Mongolian and Tian Shan group of headdresses with a capital-shaped top (Tishkin, Pilipenko, 2016: 22). Only two items found in Russia can be regarded as its direct typological equivalents: a bocca from the cemetery of Teleutsky Vzvoz-1, in southwestern Siberia (Tishkin, 2009: 126– 128), and a headdress from the cemetery of Saryg-Khaya, in Tuva (Dluzhnevskaya, Savinov, 2007: 164). Boccas of this type have also been reported from Kyrgyzstan

(Tabaldiev, 1996; Orozbekova, Akmatov, 2016: 176–181) and Mongolia (Erdenebat, 2010). Noteworthy is a similar bocca of the Mongolian and Tian Shan type from China (Inner Mongolia), deposited in the Mardjani Foundation in Moscow.

A wonderful petroglyphic ink image of a Mongolian woman wearing a bocca with a capital-shaped top, dating to the 13th–14th century, was found by A.P. Okladnikov on a slope of Bogdo-Uul mountain (the Mongolian Altai) (1962: Fig. 19). Noteworthy also are the portraits of the Yuan Dynasty empresses in China wearing headdresses of the bocca type, which are deposited in the National Palace Museum in Taipei (Erdenebat, 2006: Fig. 2–8, 12a ; 14–28, 55a ).

The Mongolian headdresses of the Mongolian and Tian Shan type (with a capital-shaped top) were described by the European explorers Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck in the 13th century. Let us cite the most remarkable fragments: “…they [Mongolian women – the Authors ] wore adornment on their heads named bocca and made of bark or other light materials. This adornment is round and as large as a man can grasp it with both arms. The headdress is cubit long or longer, topped with a rectangular part, looking like a column capital. They cover this bocca with a precious silk fabric; the bocca is hollow inside, and in the middle, over the capital, or over the abovementioned rectangle, they put a stick of stems, feathers, or twigs one cubit high or higher. This stick is decorated with peacock feathers on top; and around it, feathers from a drake’s tail are placed, as well as precious stones. Wealthy ladies put this adornment on top of their heads and tighten it with a fur cap (almuccia) having a special opening on top. They scrape back their hair into a knot and hide it inside the bocca, which is then tightly tied up under the chin” (Carpine, Rubruck, 1911: 77). Rubruck’s evidence is confirmed and supplemented by the earlier information of Pian del Carpine: “…this [headdress] is getting wider from bottom to top. On top, there is one long and thin stick of gold, silver, or wood, or even of feather. And this [headdress] is sewn upon a cap, which extends to the shoulders. Both the cap and the abovementioned headdress are covered with ‘bucarano seu purpura vel baldachino’. A woman never goes out without such a headdress, and other women recognize her by her headdress” (Puteshestviya…, 1957: 27).

All available data testify that this headdress was an attribute of the married woman’s costume; women wore it during various rituals, such as a wedding (Myskov, 2015: 201), a palace ceremony, or a guest-welcoming ceremony, and also in everyday life (see, e.g., (Xi You Ji…, 1995: 300, Luvsan Danzan…, 1973: 72)). E.P. Myskov, at the end of the 20th century, proposed that shape and name of the medieval Mongolian female headdress were related to bogto (‘long bone of sheep’s foreleg’), which was commonly used in the wedding ritual (1995: 39–40). However, he later tended to believe that the headdress symbolized the World Tree (2015: 204). M.V. Gorelik argued that bocca was one of the markers of the imperial Mongol culture (2012: 192).

The present authors have not found any information concerning bocca use in burial practice, either in the written or the visual art sources. Archaeological data suggest that the place and number of such headdresses in the grave were not regulated (Myskov, 2015). Placement of the bocca in a position “on the head” is known in the burial practice (e.g., (Dluzhnevskaya, Savinov, 2007)); though this variant is rare (Myskov, 1995: 42). At archaeological sites in Kyrgyzstan, female headdresses were usually put either to the left or to the right of the skull, or above it; and also on the chest or at the knees. In some cases, the bocca partially covered the front of the skull or only the mandible. It means that bocca was not put on the head during the burial, or it was taken off immediately before inhumation. Myskov believed that the headdress was put “into the grave not as a piece of clothing, but as a special grave good with a definite meaning. …The presence of a bocca or a cap in the grave primarily marked the sex and age of a buried woman, or her social status” (Ibid.).

Conclusions

A comparatively small number of finds and their poor degree of preservation hamper identification of the bocca’s origin and symbolism. New intact burials with boccas are therefore of great importance.

The headdresses from the cemeteries of Krokhalevka-5 and Basandayka (the Tomsk region of the Tom) (Pilipenko, 2003) are the northernmost specimens of the bocca in Asia. The bocca under study suggests an age of the 13th– 14th century for the relevant part of the Krokhalevka-5 medieval cemetery. This piece of clothing testifies to the cultural impact of the Mongol Empire on the population of the Novosibirsk region of the Ob. Notably, features of the burial-practice traced at this mini-necropolis generally conform to the rituals of the local forest-steppe population, rather than those of the Mongolian tribes (Adamov, 2000; Molodin, Soloviev, 2007; Marchenko et al., 2017). Bocca’s remains (as well as the silk items, requiring special study) recovered from burial 27 were prestigious imported goods marking the high social status of the buried woman, and also (indirectly) of the whole community that created this ancestral necropolis in mound 75. The woman’s skull from burial 27 (for its craniological description see (Kishkurno et al., 2018)), being part of the medieval series of the Krokhalevka-5 cemetery, shows traits typical of the Central Asian anthropological complex. This is a distinct feature of the

Krokhalevka population as compared to other medieval groups of the Novosibirsk region of the Ob, dominated by the taiga component associated with the Western Siberian anthropological pattern (Pozdnyakov, 2006: 37–38; 2008: 361, 362). These data, and also the occurrence of imported goods (bocca, silk items) in the grave, suggest closer interrelations (including biological) between the Krokhalevka population and the groups representing the imperial Mongol culture.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. A.I. Soloviev for his valuable advice during the field studies and this paper’s preparation.