A runic inscription at Sarykoby (Southeastern Altai)

Автор: Erdal M., Kubarev G.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Paleoenvironment, the stone age

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145465

IDR: 145145465 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.4.093-098

Текст обзорной статьи A runic inscription at Sarykoby (Southeastern Altai)

The history of research into Old Turkic epigraphy of the Altai started two centuries ago. In 1818, the well-known explorer of Siberia, G.I. Spassky, first published the tracing of a runic inscription from the valley of the Charysh River. In 1865, Academician V.V. Radlov found another runic inscription carved on the bottom of a silver vessel during the excavations of kurgans near the village of Katanda. However, the inscription did not attract much attention on his part and was first read at the very beginning of the 20th century by his student, P.M. Melioransky. Individual runic inscriptions on the items from Old Turkic burials were discovered in the 1930s by S.V. Kiselev, L.A. Evtyukhova, S.M. Sergeev, and A.P. Markov. The Old Turkic epigraphy of the Altai was particularly actively studied in the second half of the 20th century. Numerous inscriptions were found on rocks and steles in Central and Southern Altai. It is enough to say that the petroglyphic site in Kalbak-Tash I is still the largest accumulation of rock runic inscriptions of the Old Turkic period in the territory of not only the Altai Republic, but all of Russia (Kubarev V.D., 2011: 9 app. IV; Tybykova, Nevskaya, Erdal, 2012: 4, 69). Scholars, such as A.I. Minorsky, A.P. Okladnikov, B.K. Kadikov, V.D. Kubarev, V.A. Kocheev and others, have made

their contribution to the enrichment of the corpus of the Altai runic monuments. Philologists, archaeologists, and historians S.V. Kiselev, K. Seidakmatov, E.R. Tenishev, N.A. Baskakov, S.G. Klyashtorny, D.D. Vasiliev, I.L. Kyzlasov, A.T. Tybykova, M. Erdal, I.A. Nevskaya, and others undertook the translation of these texts in different years. Their research has resulted in recently published comprehensive work (Tybykova, Nevskaya, Erdal, 2012; Vasiliev, 2013; Konkobaev, Useev, Shabdanaliev, 2015). The catalog of Old Turkic runic monuments contained only 90 short texts from the territory of the Altai (Tybykova, Nevskaya, Erdal, 2012: 32–43), while there were already 101 texts in the recently published atlas (Konkobaev, Useev, Shabdanaliev, 2015: 4, 302–340). After new finds (Tugusheva, Klyashtorny, Kubarev, 2014; Kubarev G.V., 2016; Kindikov B.M., Kindikov I.B., 2018: 18–19, 35–36, 44, 57, 61), including those which have not yet been published, their number today may reach 110–120. In 2018, a new runic inscription was discovered in the Chuya steppe.

Location and description of the inscription

During the survey by the Chuya team of the IAET SB RAS, at least six new petroglyphic locations were found on the northern spurs of the Saylyugem Ridge, stretching 18–20 km from the Zhalgyz-Tobe Mountain to the Buraty River. The runic inscription was found in a small group of petroglyphs in the Sarykoby (Altai ‘yellow, ginger-color ravine’) site located about 3 km southwest of the village of Zhana-Aul (Fig. 1). Up to a hundred figures of animals and people occur in several compositions at this site. The vast majority of these was made using a pecking technique, and belongs to the Late Bronze Age–Early Iron Age.

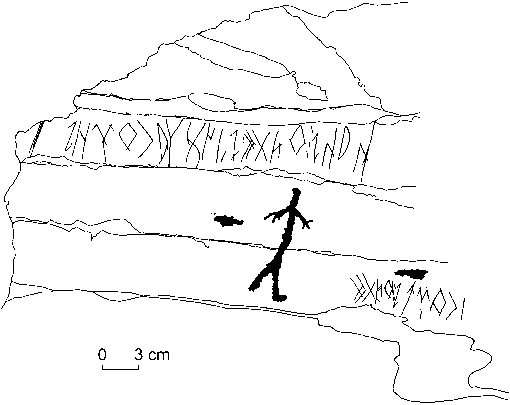

The runic inscription was a part of the composition measuring 100 × 110 cm and unusual in the content of its representations. Petroglyphs were drawn on a horizontal rock surface, which had a heavy desert varnish. The composition included 22 figures of animals and people. In the center were large images of running deer with branching antlers, as well as a bear, and four birds resembling cranes in a line (Kubarev G.V., 2018: Fig. 2). This composition can be called the most conspicuous in the small petroglyphic complex of Sarykoby. The runic inscription was drawn in its upper northwestern part (Fig. 2).

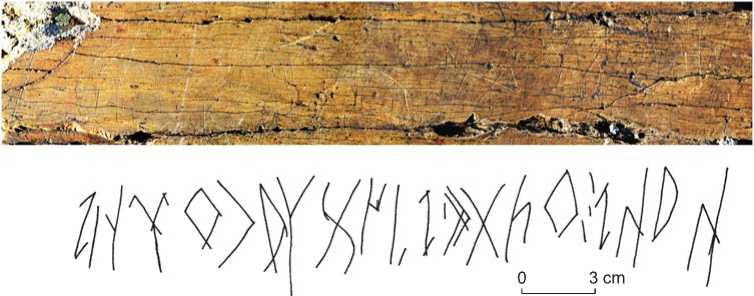

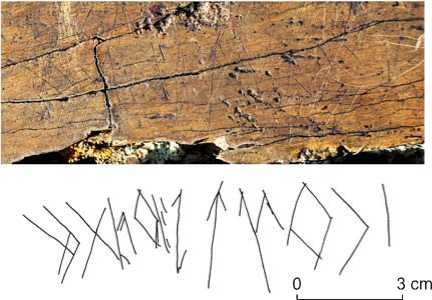

The first line of the inscription was located horizontally (taking into account the general orientation of the early petroglyphs on the rock surface) and had 21 characters (Fig. 2, 3). It was inscribed by its author into a natural “canvas”—a horizontal strip formed by two cracks. The last character almost joined the edge of the rock surface. Three oblique lines closely spaced to each other were carved 2.5 cm from it. The second line of 13 characters (see Fig. 2, 4) was written 8 cm down from the beginning of the first line. The lines were parallel to each other. The height of the characters ranged from 3 to 5 cm and was 3.5 cm on average. Some of the characters, especially in the second line, were located very close to each other. They were carved with a sharp item in one step, were strongly varnished, and therefore could be clearly distinguishable only in natural sunlight from the side. Besides two amorphous spots (see Fig. 2), the lines were separated by the pecked human figure, which, judging by the image of three-fingered hands, belongs to the

Fig. 1 . Location of the petroglyphic site of Sarykoby.

Fig. 2 . Tracing of two lines of the runic inscription.

Fig. 3 . Photograph and tracing of the first line of the runic inscription.

Late Bronze Age. It is difficult to explain why the author wrote the second line of the inscription so far from the first line under which there was more than enough space. Nevertheless, it was engraved separately, and was literally squeezed between the hole and the pecked spot.

Interpretation of the inscription

The reading and interpretation of the inscription were based on numerous photographs and careful tracings made by one of the authors of this article in the field. Copying was made on transparent polymeric materials with the subsequent improvement of the drawing using photographs. Both the lines of the inscription and groups of individual characters were photographed so it would be possible to reach the maximum zoom of the digital image. Copying the inscription’s characters was complicated by the fact that they were shallowly cut by a sharp item, as well as by the presence of possibly random lines, naturally appearing on the horizontal surface of the rock (from the passage of livestock, displacement of small stones, etc.). Nevertheless, the vast majority of the characters were clearly distinguishable, especially in lateral sunlight.

Despite the fact that the lines were not very close to each other, we have no reasons to speak about two separate inscriptions. The lines were interconnected by distinctive features—two graphic and one orthographic. In both lines, characters A were inverted as compared to the canonical form of this grapheme, and characters b2 had the main form of lozenge with the minimal extension (if any) of the lines below. In none of these lines were the vowels of the verbs biti- and ber- expressed explicitly.

The transliteration of the inscription using the system commonly used for the Turkic runic script is as follows:

k1 y1 k1 A : b2 t2 d2 m : A : s2 ẅ z l2 y1 w b2 r2 ŋ2 A s2 w b2 r2 I p A : b2 t2 d2 m

Comparing this transliteration with the tracing of the inscription, we need to discuss several points. In the first

Fig. 4 . Photograph and tracing of the second line of the runic inscription.

line, after the word b2t2d2m , a vertical dividing mark was carved in the middle level of the inscription line. Then, after the character A , there was another mark at the lower level. Usually the character separating the words consisted of two dashes located one below the other. According to M. Erdal, both dashes were related to the same word-separating character, which in transliteration was indicated by the colon (the generally accepted designation of a word separator consisting of two parts). They should probably be interpreted in this way, or else one of these dashes can be considered a random line. The dash after the character A corresponds to what we see in other places of the inscription, but the line in front of it also makes sense, since character A does not actually belong to the word biti-d-im .

The arrow-shaped character (wq) in the second line should probably be read as I: the “hook” visible on its front (left) side seems to be a part of a much longer slanting line on the rock (or rather, two natural lines which were parallel in this place). The character I, according to Erdal, was followed by the character p, which had not been noticed by G.V. Kubarev. In the case that this character was not there, Erdal suggested interpreting I in front of it as the inverted p, otherwise, the sequence of characters such as b2r2I or s2wb2r2I would not have made sense. The penultimate character of the second line, transmitted by a vertical line on the tracing, should be interpreted as character s2. Since the use of this letter in this context does not make sense, Erdal suggested that the line should be considered random.

Here is the transcription of the text, adding the implied vowels in brackets:

k(a)y(a)ka b(i)t(i)d(i)m - a! sozl(a)yu b(e)r(i)y - a!

su b(e)r(i)p - ä b(i)t(i)d(i)m.

The translation of the inscription with two possible options in the second line is as follows:

I have written on the rock, ah! Oh, please speak!

Give me luck (or “Going to the battle”) – oh – I have written (this).

Comments to the translation

According to Erdal, the character A , which is not a morphological element of the previous word, should be interpreted as exclamation, and not as a simple word separator, although the problem of its meaning has not been completely resolved (see (Erdal, 2002: 56, Fu₽n. 12), where it was shown that this element is synharmonic, that is, obeys the rule of the vowel harmony). The translation of the word ber- as ‘please’ needs an explanation. Erdal has already written about the use of this verb, primarily meaning ‘give’ and having only secondary meaning of ‘graciously (kindly)’ (Erdal, 2004: 260–261)*.

The spelling of the first word in the second line is irregular, since the consonant s2 , usually combined only with the front vowels, was used with the back w . This is not a blatant violation of the spelling rules of runic writing, since irregularities in the use of characters denoting sibilants abundantly appeared even in the Orkhon texts**. Yet the irregularity in writing the segment s2w does not make it possible to answer the question of how to read that word: in phonetic transcription with the front or back vowel. In the former case, it could be sü ‘army’, or sö ‘the distant past’, or the borrowed Chinese word sü ‘foreword’; in the latter case so ‘chain, fetters’. Another, fifth reading could be the noun meaning ‘glory (triumph)’, which is written as suu or süü in the Old Uyghur sources that will be discussed below. Three possible options (‘the distant past’, ‘foreword’, or ‘chain’) make no sense in this

*Ibid., on p. 261, two examples with sözläyü ber- were mentioned.

**See also the suffix - yU in the first line, which was written with the characters used in the words with back vowels, although the stem sözlä - has front vowels.

particular context, as the Object to the Verb ber- ‘to give’ and the author of the inscription as the Subject.

If we assume that b2r2 should be read as bar- ‘go’, despite the presence of front consonants and due to the abovementioned violations of synharmony, it is possible to suggest the reading of sü as ‘army’. Then sü bar- should be translated as ‘go to the battle’, even though the first word has the form of the Nominative Case and not Dative Case. This interpretation is based on the parallel with the expression sU yori- (yori- ‘go’, is also an intransitive verb), which occurs in three places of the Orkhon inscriptions: oydUn kagangaru sU yorilim - “Let us fight the war against the eastern Khagan” in line No. 5 of the inscription in honor of Tonyukuk, the repetition of sü yorilim with the same meaning in line No. 11 of the same text, and kok oyUg yoguru sU yorip... suvsiz ka^dim -“I have passed (with) the army without water… crossing the Blue Desert” on the southeastern side of the monument to Bilge Khagan. Words in the Nominative Case with Dative content combined with intransitive verbs are quite rare in Old Turkic language*. The main problem with this interpretation is the writing of bar- with the consonants combined with front vowels; it is possible, although in fact it is very unlikely, that the type of the runic script with which the writer was familiar, did not include characters b1 and r1 **.

The word su/sü ‘glory, imperial state, greatness, happiness’ was usually written with two vowels (Ligeti, 1973: 2–6). L. Ligeti found this word in a number of Uyghur and Mongolian texts of the Yuan dynasty, where it was always used in relation to the Mongol Emperor. In the Uyghur language, derivatives of this word have suffixes with both front and back vowels; in the Mongolian language only with front vowels, although Ligeti was able to etymologically connect them with several other Mongolian lexemes which also had front vowels. Since he found the use of this noun in Uyghur texts only during the period of the Mongol rule, Ligeti considered it to be a Mongolian borrowing in the Old Uyghur language, which has been preserved in the Chagatai language. Nevertheless, in the Manichaean text published by P. Zieme, this word was present in the expression ulug kutun suun yalanar ‘burning with enormous greatness and glory’ (line 435) (1975). The words kut and suu were used here as the Binomial in the Instrumental Case. Kut means ‘heaven’s benevolence’; hence, ‘luck’ and ‘happiness’, which are quite synonymous with suu. Their use with the verb yal-in + a-, formed from yal-in, ‘flame’, is not unexpected: early Mongolian manuscripts contained the binomial expression suu jali, in which jali was a Turkic loanwordyalin. In a footnote, Ligety pointed out that in later woodcut editions, suu jali was replaced by cog jali, where cog ‘glow, heat’ was also a Turkic loanword. According to E. Wilkins (oral communication), the Uyghur words su/sü recorded at the same time also belonged to the Yuan period and were usually used for describing the Emperor. Ligeti was correct in his etymology, and there are no doubts in his reading of the early Manichaean manuscript. Therefore, this word is one of the few early Mongolian borrowings in the Old Uygur language*. In this case, it could have been used in the Sarykoby inscription, even if it was of Mongolian origin.

The phrase su/sü ber- is synonymous with kut ber-‘bless someone’. The latter phrase has been found in the second prediction from “Ïrq bitig”—a book of omens, also written in runic script. God says there: Kut bergäy män: – “I will bring (you) good luck”. The person who made the Sarykoby inscription could have believed in its ability to convey its blessing to those who would read it. This interpretation of the second line can be associated with the phrase sozlayti beriy-a! in the first line. Whom was this imperative addressed to? It might have been a polite appeal to a person or being, or else the author could have meant many recipients. We do not know whether the inscription was an invitation to dialogue, or call to prayer or blessing. Its content resembles two sentences in a Yenisei runic inscription** discovered by A.V. Adrianov: (a)sizni sozl(a)ti b(i)tiyur b(a)n. uk(u)gli k(i)si (a)rka sözl(ä)yü b(e)rd(i)m – “I write, making grief (sorrow) speak. I spoke with the understanding people”*** (Erdal, 1998: 89). The author of that inscription presents himself as the initiator of the dialogue. If he makes his sorrow speak, can it be the case that the author of the analyzed text also “invites” his own words to “speak” and express su/sü ‘blessing’?

The word which can be read as (ä)sizni and interpreted as ‘sorrow’ (in the accusative case) in the Yenisei inscription, can also be read as sizni— the second person plural pronoun in the accusative case, meaning plural recipients and/or polite address to one or many persons. The phrase sizni sözl(ä)ti b(i)tiyür b(ä)n could mean “I write making you speak”. Such an interpretation of that inscription, “making its reader speak”, would support our reading and interpretation of the Sarykoby inscription.

Conclusions

The Sarykoby inscription is located on a horizontal surface in a very inconspicuous place; the characters are small in size and were carved shallowly in one step—all this confirms the opinion of many scholars about the intimate nature of many Altai runic inscriptions (Kyzlasov, 2005: 435; Tybykova, Nevskaya, Erdal, 2012: 17). They were not intended for everybody’s viewing and reading. The attention of the author of the Sarykoby inscription was undoubtedly attracted by large and expertly executed rock composition of the Late Bronze Age–Early Iron Age, if for no other reason than other similar petroglyphs were absent from that place (the rest of the petroglyphs were much more modest both according to their area and number of images). Other runic inscriptions, as well as petroglyphs or graffiti of the Old Turkic period, have not been detected there. The composition depicts hunters with bows, deer with branching antlers, bear, and several birds (probably cranes). And although there is no direct connection between the content of the Sarykoby runic inscription and this rock composition, the latter might have served as a kind of pointer intended for attracting attention to the inscription.

Finding each new runic inscription in the Altai is an important scholarly discovery. This is even more true for Kosh-Agachsky District of the Republic of Altai, bordering Mongolia. To this date, 13 runic monuments are known there, while 75–80 runic inscriptions are known in Ongudaisky District (Central Altai). In addition, only five of the Kosh-Agach inscriptions were written on the rocks; the rest were carved on steles or items from burials.

Summarizing our research, we should say that we have a clearly legible, but still rather mysterious inscription, which apparently includes a borrowing from the ProtoMongolian language. Its content in a certain sense is religious-philosophical. The inscription invites the readers to dialogue, or perhaps contains a call for prayer or blessing, which manifests its originality and importance in the corpus of the Altai runic monuments.

Acknowledgement