A Set of Clothing Items from the Iyus Hoard

Автор: Golovchenko N.N.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This stud y focuses on details of clothing, belonging to the Iyus hoard, incidentally found in Khakassia in the 1970s. As in most other hoards from southwestern Siberia, this one includes elements of belt sets—buckles, plaques, pendants, and rings, paralleled by similar artifacts associated with the Tes culture of the 2nd century BC to 2nd century AD. The context of the ornaments is described, and the assembly and ritual use of belt sets are reconstructed. The composition of the Iyus hoard mirrors the process of a new Xiongnu clothing tradition being adopted by native south Siberians in their ritual and everyday practices. The “Scythian” component of the Iyus hoard is represented by rarities—ancient artifacts worn by natives in later times, and by replicas of ancient ornaments, whereas the “Xiongnu” component was more adaptive and includes items commonly used in everyday life. The co-occurrence of “Scythian” and “Xiongnu” artifacts within the same ritual assemblage testifies to the symbolic use of belt sets, evidenced by mid-1st millennium BC sites in southern Siberia.

Iyus hoard, belt set, transcultural complex, Early Iron Age, Xiongnu-Xianbei period, rituals

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146850

IDR: 145146850 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.1.116-125

Текст научной статьи A Set of Clothing Items from the Iyus Hoard

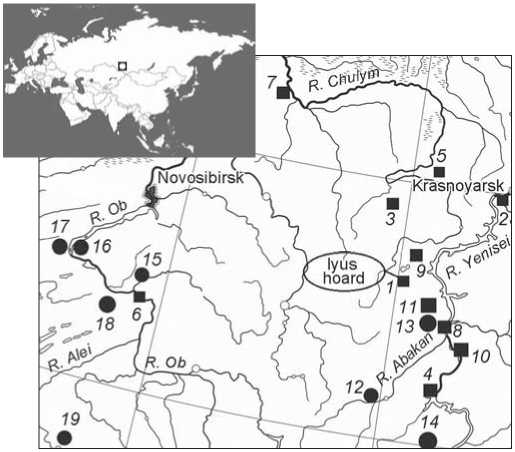

The Iyus hoard was discovered by S.A. Fefelov in the 1970s close to Lake Sarat, on the right bank of the Bely Iyus River in Khakassia. This hoard is rightly considered to be one of the richest finds associated with the Xiongnu-Xianbei period (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2011). Just like other hoards of the Chulym region (Fig. 1), which links Khakassia with the Upper Ob basin, this assemblage was formed as a set of ritual attributes of the 5th–1st centuries BC on the eve of the Xiongnu invasion in the southern regions of Siberia, and hidden in the late 1st millennium BC to early 1st millennium AD. The hoard reflects the processes of active interaction between various cultural traditions occurring in that period. Assuming that the composition of the hoard was assembled purposefully, it is an important and unique source for studying the outfit and ritual practices of the ancient population living in southern Siberia. The aim of this study is to analyze and interpret the set of clothing items revealed by the Iyus hoard.

Material

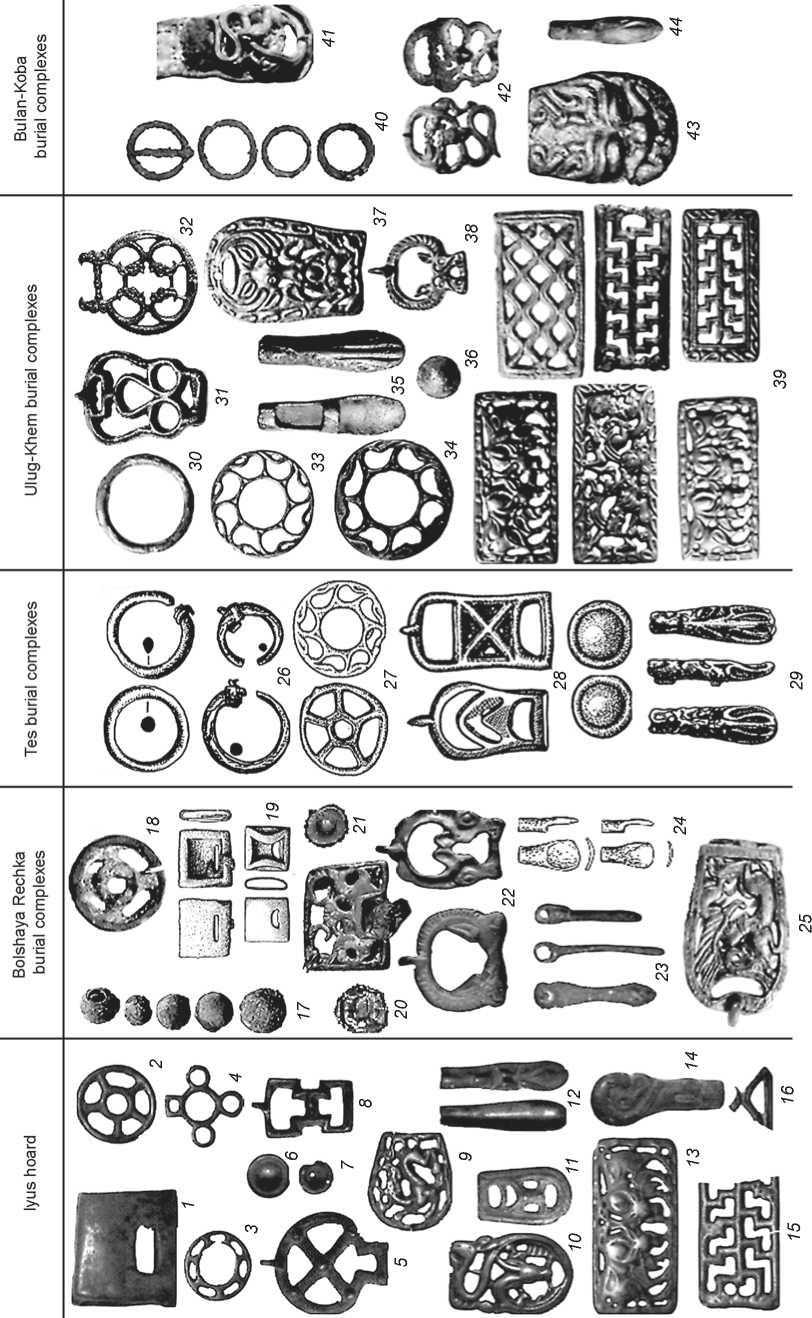

The Iyus hoard includes household and cultic items— 271 specimens (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: 33). The set of clothing items comprises 216 specimens, amounting to 79.7 % of the total number of finds (Fig. 2, 1–16 ).

The set is functionally homogeneous. Most of it consists of belt fittings: 14 buckles (5.17 % of the total number of finds), two clips (0.74 %), three tubular beads (1.11 %), seven belt plates and their fragments (2.58 %), 17 spoon-shaped, bracket-shaped, and other pendants (6.27 %), 18 rings (6.64 %), and five plaques (1.85 %). The hoard contains 150 beads (55.35 %), which could have also belonged to a belt set. Two whetstones (0.74 %) can also be considered as items hanging from the belt.

Fig. 1 . Hoards ( A ) and archaeological sites with materials similar to the items from the Iyus hoard ( B ), in southern Siberia.

A : 1 – Iyus; 2 – Esaulsky; 3 – Kosogol; 4 – Sayanogorsk; 5 – Aidashinskaya Cave; 6 – Novoobintsevo; 7 – Burbinsky “hoard”;

8 – Askyrovka; 9 – Pervy Dzhirim; 10 – Lugavskoye; 11 – Znamenka. B : 1 2 – Esino; 13 – Chernoye Ozero I, “Blizhny”;

14 – Ala Tei; 15 – Novotroitskoye-1, -2; 16 – Bystrovka-2; 17 – Maslyakha-1; 18 – Rogozikha-1; 19 – Lokot-4a.

A.V. Davydova and S.S. Minyaev give the following description of various kinds of the Xiongnu belt set: “The most sophisticated set involved a large number of various items, including bronze ornaments—a couple of large plate-buckles, a couple of openwork rings, a couple of buttons, plaques, a couple or more of spoon-shaped clasps, as well as beads and various pendants made of minerals. Simpler belts were decorated with small bronze plaques and pendants. In the simplest version, there was only the iron buckle on the belt of the buried person” (2008: 49). If we assume that a complete belt set contained two buckles (this was not always the case with the evidence from the burial sites of the Scythian and Xiongnu-Xianbei periods), the set of things from the hoard under discussion must have belonged to at least seven rich belts. Given this assumption, eleven groups of interconnected items (“bundles”), which can be divided into several variants, deserve our special consideration.

The first variant is bundles of typologically homogeneous things: No. 75* – four bronze buckles; No. 79 and 80 – one ring each; No. 83 and 84 – two pendants each, and No. 85 – one pendant. The second variant is bundles of typologically heterogeneous things: No. 76 – one buckle, seven rings, one tubular bead, and two beads; No. 77 – pendant, votive mirror, and ring; No. 78 – ring and four spoon-shaped pendants; No. 81 – ring and tubular bead; No. 82 – two spoon-shaped pendants and plaque. It is possible that some of these bundles were formed as a result of the destruction of the initially more representative sets.

The quantitative and material composition of bundles in the Iyus hoard generally corresponds to elements of clothing and fittings of composite belts that were found in the Tes and other contemporaneous burial complexes (Fig. 2, 26–29 ). For example, grave 3 in kurgan 7 at the Esino I site, in the south of the Minusinsk Basin, contained two pendants made of drilled animal teeth and a fragment of an iron ring found among the chest bones of a buried woman, which set is similar in composition to bundle No. 78 (Savinov, 2009: 163). A set of an openwork ring and two spoon-shaped pendants was

■А •B found in grave 24 at Esino III; this set shows parallels with items from bundles No. 78, 83, and 84 (Ibid.: 157). Fragments of an iron ring were found on the left pelvic bone of a child buried in grave 3 of the Blizhny kurgan, which correspond to the composition of bundles No. 79 and 80 (Ibid.: 141). A set of three rings and one or two buckles from grave 10 of kurgan 1 at the Chernoye Ozero I cemetery is comparable in composition to bundle No. 76 (Ibid.: 124). A set of a bronze rectangular buckle, two rings, and two spoon-shaped pendants from grave 18 at the same site (Ibid.: 126) can be correlated with bundles No. 76, 78–80, 83, and 84.

The list of similar correspondences to the abovementioned bundles can be continued (Ibid.: 161–162; Kuzmin, 2011: Pl. 75, 76). A series of bronze items from grave 30 at Esino III, which contained two buckles, a fragment of a spoon-shaped pendant, a wheel-shaped pendant, three rings, and four round button-plates, found outside the context of skeletal remains from several buried persons (Savinov, 2009: 161: pl. XLVII, 1–12 ), can be compared to bundles No. 76 and 78. The belt set of a woman buried in grave 9 of kurgan 1 at Chernoye Ozero I included two bronze rings, one of which retained a leather strap, bronze tubular beads, two spoon-shaped pendants, and a round iron buckle (Ibid.: 122–124, pl. XXIV); that set shows parallels to bundles No. 76, 78, and 81.

Leather straps of the Iyus bundles were stitched, and resemble similar items made of organic materials not only from the Tes complexes, but also the Early Iron Age items found in the Altai (Shulga, 2008: 219, fig. 28, 2 , 2a ). Similar artifacts are also known from Tuva. Probably the most interesting among them was a female belt set found in burial 47 at the Ala Tei-1 cemetery. Traces of organic matter, two bronze buckles with figures of dragons

Fig. 2 . Elements of belt fittings from the Iyus hoard ( 1–16 ) (after (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: Fig. 31)) and burial complexes of the cultures of Bolshaya Rechka ( 17–25 ), Tes ( 26–29 ), Ulug-Khem ( 30–39 ), and Bulan-Koba ( 40–44 ).

17–25 – collection of the Museum of Local History at the Altai State Pedagogical University (Shulga, 2003: 148, fig. 6; Shulga, Umansky, Mogilnikov, 2009: Fig. 115, 6, 7); 26–29 – (Savinov, 2009: Pl. XXIV, XXV, XLVII); 30–39 – (Kilunovskaya, Leus, 2018: Fig. 11, 12, 16); 40–44 – (Istoriya Altaya, 2019: Fig. 2.198).

(similar to the Iyus buckles) on the wooden base, bronze six-rayed plaques, as well as large number of tubular and regular beads, have been preserved from the belt (Kilunovskaya, Leus, 2018: 129–130). A representative set of beads was also found in a female belt set from grave 1 at Esino III (Savinov, 2009: 145).

Although the items from the Iyus hoard show similarity to the objects discovered in the burials (Fig. 2), in terms of their total number, the clothing items do not correspond to the standard set of items from the Early Iron Age Siberian burials with a large number of finds. However, in terms of the ratio of clothing items and things of other categories, the Iyus hoard is well comparable with the evidence from other Siberian hoards. For instance, the “hoard” from the settlement of Barsov Gorodok I/20 included a total of 54 items, 53 of which were clothing ornaments and a bead (Beltikova, Borzunov, 2017: 128). The Esaulsky hoard, discovered near the city of Krasnoyarsk, contained 116 artifacts, including 65 various pendants (72.41 %) (Nikolaev, 1961: 280–283). The Kosogol hoard contained about two hundred items, including 130 (65 %) plaques and buckles made in the animal style, and other ornaments (Nashchekin, 1967). The Ai-Dai (Sayanogorsk) hoard contained 277 items (archaic Scythian objects, items of Chinese appearance, and many Tes ornaments), including 172 (62.09 %) rings, spoon-shaped pendants, buckles, tubular beads, clips, openwork plaques, and button-plaques (Pshenitsyna, Khavrin, 2015: 71–72). The assemblage from Aidashinskaya Cave contained 111 items, including 66 (59.46 %) bronze plates, rings, tubular beads, fragments of bracelets, and various pendants (Molodin, Bobrov, Ravnushkin, 1980: 24–58). The Gornoknyazevsk hoard consisted of 25 items, including 11 objects that can be described as clothing ornaments (44 % including “plaque mirrors”) (Fedorova, Gusev, Podosenova, 2016: 12–24). Ten (37.04 %) out of 27 items from the Novoobintsevo hoard, submitted to the Altai State Museum of Local History (in total, about 40 items have been identified), were probably related to clothing, primarily representing belt fittings (Borodaev, 1987). The Burbinsky “hoard” included 12 items presumably originating from a destroyed burial, of which at least 4 (33.33 %) can be reliably correlated with the clothing set (Borodovsky, Troitskaya, 1992). The Kholmogory hoard consisted of 193 items, including 58 (30.05 %) processed anthropomorphic and ornithomorphic representations with loops for fastening, rectangular belt plaque-plates, round plaques, and beads (Zykov, Fedorova, 2001: 96– 113). The Raduzhny “hoard” included 245 items and their fragments, of which 40 (16.33 %) were clothing accessories and ornaments (belt onlays, epaulette-like clasps, anthropomorphic pendant, beads, fragments of silver plates and wire). In addition, some fragments of fur ware can be considered as belonging to the set of clothing items (Gordienko, 2007: 63).

Such hoards of the Middle Yenisei region as the Pervy Dzhirim, Lugavskoye, Askyrovka, etc. also contained the set of clothing items (Borodovsky, Oborin, 2018, 2021). It is important that despite the differences in the set of clothing items, these assemblages were similar in the presence of intact and fragmented elements of belt set, with a small number or total absence of personal ornaments*—earrings, hairpins, braid ornaments, bracelets, rings, or torques.

Artistic bronzes appearing in the assemblages, along with undecorated items (rings, tubular beads, and clips), make it possible to focus not only on their aesthetic characteristics, but also on specific aspects of assembling the hoard and the ritual use of belts.

Interpretation

As Borodovsky and Larichev observed, the set of items from the Iyus hoard reflected traditions of hoard assembly typical of the turn of the Late Scythian and Early Xiongnu periods (2013: 56). This conclusion was based on the cultural and chronological multicomponent nature of the assemblage under consideration. It is certainly difficult to interpret it, but it was not the only one of that kind. The hoard contained both “Scythian” and “Xiongnu” transcultural components (Ibid.: Fig. 31) relating to belt fittings.

The “Scythian” component of the hoard was not only the so-called Tagar bronzes (cauldron, pommels, mirrors), but also bronze slotted belt clips (Fig. 2, 1 ), a conical bead, wheel-shaped “pendants” (Fig. 2, 2 , 3 ), silver plaque (Fig. 2, 7 ), and probably whetstones. According to the observation of A.I. Martynov (1979: 115), confirmed by later studies (Savinov, 2012: 15–25), leather belts with buckles and other ornaments were generally not typical of the Tagar culture.

The only silver umbo-shaped plaque No. 74 from the Iyus hoard (Fig. 2, 7 ), showing parallels to the finds from the burial complexes dated to the 2nd century BC– 1st century AD, was similar to archaic ornaments from the Novotroitskoye necropolis; it can be interpreted as decorative element of a belt set (Fig. 2, 20 , 21 ) (Shulga, Umansky, Mogilnikov, 2009: Fig. 100, 3 ).

Belt accessories also included slotted clips (Fig. 2, 1 ) dated to the period from the 6th–5th to the 3rd centuries BC. Their parallels have been found in numerous burial complexes of the Scythian period in southern Siberia (Fig. 2, 19 ), in the later Tes sites (grave 1 at Esino III

(Savinov, 2009: 145)), and in the Middle Yenisei hoards, such as the Pervy Balankul hoard found near Lake Balankul, north of the town of Askiz (Borodovsky, Oborin, 2021: Fig. 5).

Conical beads appear widely among the evidence from the burial grounds of the second half of the 1st millennium BC in southwestern Siberia (Shulga, Umansky, Mogilnikov, 2009: 315, fig. 115, 28 , 29 ). They have also been a part of the same Pervy Balankul hoard (Borodovsky, Oborin, 2021: Fig. 5). Such items have been found in grave 3 (undisturbed) of kurgan 15 at the Novotroitskoye-2 cemetery (the Upper Ob region)—these were a part of a belt set without buckles along with a kochedyk bent wedge-shaped element (Fig. 2, 23), as well as ribbed and slotted clips (Shulga, Umansky, Mogilnikov, 2009: Fig. 77); and also in a grave near kurgan 17a at Novotroitskoye-1—these were a part of a belt set without buckles, but with a ribbed clip and metal belt hook stylized as the image of a griffin’s head (Ibid.: Fig. 29).

Female burial complexes of the Scythian period included bronze wheel-shaped items interpreted as spindle whorls (Fig. 2, 2 , 18 , 27 ). One such item, with the remains of a wooden rod in the central hole, was found in grave 2 of kurgan 5 at Novotroitskoye-2 (Fig. 2, 18 ) (Shulga, Umansky, Mogilnikov, 2009: 79–80); another item of this kind was discovered at the Chekanovsky Log-2 burial ground in the area of Gilevo Reservoir (northwestern Altai) (Demin, Sitnikov, 1998: 95, Fig. 1, 6 ), and another one in kurgan 7 at the Bystrovka-2 burial ground (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: 39). Wheel-shaped items appear among the evidence from the cemeteries of Rogozikha-1 (in the vicinity of the town of Pavlovsk), and Maslyakha-1 (located on the border of the Altai Territory with Novosibirsk Region) (Shamshin, Navrotsky, 1986: 105; Mogilnikov, Umansky, 1992: 80, Fig. 6, 9 ). Such an artifact was a part of the Kosogol hoard found on the shore of Lake Kosogol near the town of Sharypovo in the Krasnoyarsk Territory (Martynov, 1979: Pl. 47, 35 ).

Notably, “wheels” in the explored Bolshaya Rechka burials (Novotroitskoye-2, Bystrovka-2, Maslyakha-1) were usually located in the area of the belt, while ceramic whorls were located in the area of the head and femurs of the buried persons. “Wheels” could be placed into common receptacles together with other items (metal cauldron in the Iyus hoard) or separately (stone incense burner in Rogozikha-1). V.A. Mogilnikov observed: “By the 3rd–2nd centuries BC, the shape of the wheels had changed. Instead of spokes, marked holes in the disk appeared. The wheels could have been losing their cultic function, turning into the spindle whorl” (Mogilnikov, 1997: 87). The available sources point rather to the opposite process: at the turn of the eras, wheel-shaped discs, which had originally served as spindle whorls, began to be used as belt pendants (probably, as cultic items). This conclusion is indirectly supported by the similarity in the shapes of such disks with sectoral (ray-like, “solar”) ornamentation on ceramic spindle whorls, which scholars consider to be one of the earliest (Frolov, 2000), as well as the data from the functional, classificatory, and chronological analysis of belt pendants of the Late Scythian period (Teterin, 2012: 120–121). Sectoral ornamentation, as an early form of decoration, appears in the chronological summary of the solar signs from the pre-Tagar and post-Tagar periods, compiled by Martynov (1979: 134–139, pl. 52). Simple wheelshaped pendants similar to the items of the Bolshaya Rechka culture appeared earlier than more sophisticated multi-ringed and openwork pendants of the Bulan-Koba culture in the Altai, the Tes culture in the Minusinsk Basin, and the Ulug-Khem culture in Tuva, which were described in detail by Y.V. Teterin (2012: 122). Teterin has also proven that ring pendants might have been used as cultic-decorative and functional (suspensions, dispensers, buckles) elements of belt sets. In the context of our study, it is important that the Iyus hoard contained both more archaic “spindle whorl-pendants” (Fig. 2, 2) and many-ringed and openwork pendants (Fig. 2, 3, 4), with parallels found in the Tes burial complexes and complexes contemporaneous with the Tes culture (Fig. 2, 27, 33, 34) (Savinov, 2009: Pl. XLVII, 5; Kuzmin, 2011: Fig. 40, 41; Teterin, 2015: 53–55; Kilunovskaya, Leus, 2018: Fig. 16, 5–8). Teterin also emphasized that ring-shaped pendants with the inner field decorated with two to five small rings and curls from the closed complex were known only from the Iyus hoard (2012: 122). According to Teterin, small rings on the inner field of the pendants repeated the rings that appeared on the frames of individual buckles; the prototypes of these figures were extremely stylized images of the heads of birds of prey, widely appearing in the Scythian Siberian animal style of the Late Scythian and Xiongnu periods (2015: 53–54).

According to L.M. Pletneva, whetstones were left in both male and female burials in the Scythian period (2017: 73). The whetstones from the Iyus hoard can be typologically identified as rod-shaped, with straight top and oval bottom, or oval top and bottom (Ibid.: Pl. 1). According to the evidence collected by Pletneva, similar items have been found in the areas of the Bolshaya Rechka and Tagar cultures.

The “Scythian” component of the Iyus hoard includes a set of rarities—ancient artifacts used at a later time, and rare replicas—items made according to archaic models, that is, items from the preceding period preserved in a collective owing to commemorative cultic practices or obtained from grave looting.

The Xiongnu artistic bronzes in the Iyus hoard are represented by buckles with fixed prongs (Fig. 2, 5, 8), plates with figures of opposing bulls (Fig. 2, 13), fragments of plates “with snakes” and lattice ornamentation (Fig. 2, 15, 16), buckles with a dragon and a standing predator (Fig. 2, 9–11) whose head is turned back, a buckle with representation of bull’s heads, spoonshaped and bracket-shaped pendants (Fig. 2, 12, 14), and hemispherical buttons (Fig. 2, 6) (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: 39). Parallels to the above finds appear in a number of hoards from the steppes of the Middle Yenisei region (Ibid.: 39–44). Similar items include a fragment of buckle with dragon figure, and several bracket-shaped pendants from the Pervy Dzhirim hoard (Borodovsky, Oborin, 2018: Fig. 5, 9). Many similar things have been studied (Devlet, 1980; Dobzhansky, 1990). Items similar to those from the Iyus hoard have been discovered in the Tes (Fig. 2, 28, 29), Ulug-Khem (Fig. 2, 31, 32, 35–39), and Bulan-Koba (Fig. 2, 41–44) burial complexes. Burials usually contained one belt buckle, rarely two; often, as in the hoard, they have survived in fragments. The closest examples can be found among the finds from graves 1 and 30 at Esino III (Savinov, 2009: 145, pl. XLVII), grave 5 in kurgan 1 at Chernoye Ozero I (Ibid.: 122, pl. XXIII, 10), and graves 2, 15, 23, 42, and 43 at the Ala Tei-1 burial ground (Kilunovskaya, Leus, 2018: Fig. 11, 1, 3, 6, 7; 12). It is important for establishing the functional purpose of the items that burial C in grave 19 of kurgan 1 at Chernoye Ozero I contained three buckles; one of them, according to D.G. Savinov, belonged to the belt that tied the legs of the buried person (2009: 127), or to an unfastened belt laid along the buried body with the buckle turned to the feet.

In grave 23 at the Ulug-Khem site Ala Tei-1, a bronze buckle with a full-face representation of a bull (Fig. 2, 39 ), similar to the item from the Iyus hoard (Fig. 2, 13 ), was on the belt of a buried woman 20–25 years of age (Kilunovskaya, Leus, 2018: 128). Rectangular buckles depicting wiggling snakes (Fig. 2, 39 ) have been found in female burials 1 and 43 at the same cemetery (Ibid.: 137). Openwork belt buckles and spoon-shaped pendants, similar to the items in the Iyus assemblage, have been discovered at the Terezin burial ground (Fig. 2, 35 ) (Ibid.: 142–144). Common features have been revealed by metallographic analysis of the Terezin and Iyus finds (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: Pl. 2; Khavrin, 2016: Pl. 1). In the Tes female burials, openwork plates have been found in grave 3 of the southern complex of graves at the Novye Mochagi cemetery located 12 km west of the city of Sayanogorsk (Kuzmin, 2011: 281, pl. 75).

The Iyus hoard included the most numerous series of spoon-shaped pendants (11 items) and plates (7 items) in southern Siberia, with representations of a pair of bulls and dragons; this was discovered in a single individual complex (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: 43). We should mention that in the Kemerovo Region, such items appear in small numbers (Bobrov, 1979) in the burials at the cemeteries of Utinka (kurgan 5), Grishkin Log I, and in the Early Iron Age kurgan of Razliv III: at best, one or two items (Devlet, 1980: 37, pl. 1) or fragments.

Spoon-shaped pendants (Fig. 2, 12 ), similar to the Iyus pendants, have been found in both male and female burials of the Tes kurgan 1 at Chernoye Ozero I (Savinov, 2009: 122–127, pl. XXIV, 4 ; XXV, 3, 4) and grave 24 at Esino III (Ibid.: 157) (Fig. 2, 29 ). At the Ala Tei-1 site in the Upper Yenisei basin, they appeared only in male burials (Fig. 2, 35 ) (Kilunovskaya, Leus, 2018: 135, 143).

If we take into account similar horn items from the earlier sites—for example, from grave 1 in kurgan 1 at the Lokot-4a burial ground (Fig. 2, 24 ) (Shulga, 2003: Fig. 6)—spoon-shaped pendants may be dated to the 6th–3rd (2nd) centuries BC (Borodovsky, 2012: 379; Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: 43).

Another category of belt fittings of the Xiongnu period, represented in the hoard, was bronze rings (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: 43–44). Their parallels have often been found in the Tes (Fig. 2, 26 ), Ulug-Khem (Fig. 2, 30 ), and Bulan-Koba (Fig. 2, 40 ) burial complexes (for example, Esino III, graves 24 and 30 (Savinov, 2009: 157, pl. XLVII, 6–8 ), Chernoye Ozero I, kurgan 1, graves 3, 5–7, 9, 10, and 18–20 (Ibid.: Pl. XXIV; pl. XXV), Ala Tei-1, graves 38 and 47 (Kilunovskaya, Leus, 2018: Fig. 16, 1 , 2 )). In burials, they occur both together with other elements of composite belts and separately (Chernoye Ozero I, kurgan 1, graves 3, 5–7, and 10 (Savinov, 2009: Pl. XXIII, 4 , 9 , 11 )). Bronze rings were a part of both male belts (Ibid.: 124, 126) and, judging by the evidence from grave 3 (Ibid.: 141) and burial 3 in grave 20 (Ibid.: 129) of the Blizhny kurgan, female belts. A ring was the only element of the children’s belt in grave 6 of kurgan 1 at the Chernoye Ozero I cemetery (Ibid.: 123). Rings have also been found at natural features with the cultic role, such as Maslyakhinskaya Sopka now located in the water area of the Novosibirsk Reservoir (Golovchenko, Besetaev, 2021: 83, fig. 1).

Burials of the Xiongnu period typically contained rich belt sets including numerous silver items (Borodovsky et al., 2005: 12). Metallographic analysis has revealed a significant admixture of silver in the composition of individual items of the Iyus hoard, such as pendant No. 51, consisting of contiguous rings, and belt hemispherical umbo-shaped plaque No. 74 (Fig. 2, 7 ) showing parallels from the earlier sites of the Upper Ob region (Fig. 2, 20 , 21 ).

The “Xiongnu” component of the Iyus hoard is represented by the items of adaptive forms (homages), with traces of active use. The surfaces of many items are polished; images are strongly smoothed or virtually erased in the process of using the things. The closest parallels have been found in the Tes (Fig. 2, 28) and Ulug-Khem (Fig. 2, 31, 32, 37, 39) sites, as well as contemporaneous sites of the Bulan-Koba culture (Fig. 2, 41–43), identified in the Altai Mountains (Teterin, 1995: 134). Items from the Iyus hoard show similarities with the evidence from the Dyrestui burial ground (Minyaev, 2007: Pl. 6, 12, 50, 57, 80, 84, 86, 91, 104).

Thus, the Iyus hoard includes a representative series of belt fittings whose syncretic composition marks the processes of incorporation of a new, Xiongnu, set of clothing items into the cultic and everyday practices of the local population of southern Siberia. A.V. Davydova and S.S. Minyaev have suggested that the number of artistic bronzes, as well as the nature and size of the constituent parts of a belt, depended on the social status, sex, and age of the buried person (2008: 49). For example, belts with rich sets of bronze ornaments have been most frequently found in burials of elderly women (Davydova, Minyaev, 1988: 231).

The analysis has made it possible to identify the conventional features of the set of clothing items. The “male” component may be represented by a slotted clip and conical beads, pendants of certain types probably related to military paraphernalia, as well as household and cultic whetstones (Pletneva, 2017: 74). The “female” component of the hoard most likely included mirrors, beads, wheel-shaped pendants, as well as individual elements of belt fittings from the Xiongnu period (buckles and pendants).

The content of the Iyus hoard, as has been mentioned above, is determined by the presence of single and serial items, and bundles of things, as well as a few fragments of items, primarily openwork plaques (Fig. 2, 15 , 16 ). The presence of broken things in the hoard prompts us to consider the practice of cultic destruction of elements of a belt set using the evidence of the Xiongnu-Xianbei period. When analyzing burial complexes of the Early Iron Age from the Upper Ob region, Mogilnikov noted: “…it is possible that belts with removed buckles were usually placed into burials in accordance with the canons of the funeral ritual” (1997: 71). He also drew attention to the fact that tradition of placing belts or parts of belts without buckles into the graves in the Sayan-Altai persisted until the Middle Ages (Ibid.). I have already discussed the problem of interpreting a phenomenon manifested by the evidence of the Bolshaya Rechka culture—placement of unfastened male belts into burials (Golovchenko, 2021). The intentional unfastening (destruction) of a belt or its elements can be viewed as an event-oriented sacralization of a thing in the context of ritual actions. For example, unfastening a belt during the funeral, that is, the removal of a thing from its direct functional state, could have been a symbolic act reflecting the concept of the “inverted world”, according to which a damaged or broken thing would acquire lost qualities in a new posthumous life.

Manifestations of ritual destruction of belt set components have also been observed in the Tes burials. Broken buckles have been found in graves 7, 9, and 18 in kurgan 1 at Chernoye Ozero I (Savinov, 2009: 123) and in burials of levels B and C in grave 13 at Esino III (Ibid.:

152–153). A fragment of a lamellar ring was discovered in burial A of grave 20 in kurgan 1 at Chernoye Ozero I (Ibid.: 128); a fragment of a bronze ring was in a burial of level B in grave 13 at Esino III (Ibid.: 152) and a burial of level A in grave 18 at Esino III (Ibid.: 155); a fragment of an iron ring appeared in grave 3 of kurgan 7 at Esino I (Ibid.: 163) (Fig. 2, 26 ); broken spoon-shaped pendants were in grave 24 at Esino III (Ibid.: 157). Additional evidence of using event sacralization in the Tes burial practice may be the presence of unprocessed and “defective” (short pour, uncut gates) items in the burials, as well as their occurrence in non-standard contexts; for example, placement of a kochedyk bent wedge-shaped component of a belt set under the humerus bones of a woman buried in grave 17, kurgan 1, at Chernoye Ozero I (Ibid.: 126).

Discussion

Most of the hoards found in the basin of the Middle Yenisei River contained “defective”, unprocessed, damaged (with the signs of wear), or broken (fragmented) items (Borodovsky, Oborin, 2018, 2021). Some scholars considered the presence of such “scrap” in the set to be direct evidence that the hoard belonged to a caster.

According to N.P. Makarov, the main argument in favor of identifying the Iyus hoard as a hoard of a caster was the presence of metal scrap in its composition, which even included small metal grains (2013: 80). Objecting to the researcher, A.P. Borodovsky and V.E. Larichev pointed to the small number of such items in the collection under consideration (2013: 58).

The initial interpretation of the Iyus hoard as a set of “shamanic” paraphernalia (Larichev, Borodovsky, 2006: 59) (which corresponds to the traditional understanding of large collections of bronze sculptures (Spitsyn, 1906; Bobrov, 2002)) was based on statements about the presence of a large number of various pendants in the hoard, which, according to most scholars, had both utilitarian and ritual purposes, as well as bundles of things (Borodovsky, Larichev, 2013: 45), and a combination of “male” and “female” components in the same complex.

There are some examples of such interpretation of items in the literature. For example, G.V. Beltikova considered the hoard discovered at Barsova Gora as a set that included a leather belt and a breastplate with onlays, clasps, pendants, and tubular beads—attributes of a shamanic outfit (2002: 206). V.A. Borzunov suggested that these items could have been cut from a ritual outfit and buried for memorial (commemorative) purposes next to the burial (Beltikova, Borzunov, 2017: 130). V.A. Burnakov observed that in the Khakass tradition, both male and female clothing that was used in everyday life could also perform a ritual function (magical healing, prognostic, protective, sacrificial, or other) in some situations (2012: 259). The most sacralized elements of clothing traditionally included a belt with fittings. There was an opinion that universality of archetypes in archaic ideological systems, which was preserved in shamanism, created ample opportunities for their hypothetical application to archaeological artifacts (Cheremisin, Zaporozhchenko, 1996: 30). However, such interpretations always cause heated discussions.

According to Borodovsky and Larichev, the very fact of hiding a set of things in the ground may be closely connected with burial and memorial ritual practices in ancient times (2011: 204). However, the redundancy of things for one individual burial does not make it possible to consider the Iyus hoard as a set of items from a single specific outfit or series of outfits, since it does not include complete belt sets.

Analyzing cauldrons and hoards of the Early Iron Age from the Middle Yenisei region, Borodovsky and Oborin suggested interpretation of the Iyus hoard as a large collection of things hidden during the seasonal ritual of “abandoning the inventory” (2021: 130). They took into consideration that the hoards that included a set of clothing items differed from the hoard-caches with sets of tools (Borodovsky, Oborin, 2018: 96). In this context, the very fact of hiding the hoard assemblage in a cauldron was probably of special importance. Placement of miniature cauldron-shaped pendants, which were used as elements of belt fittings, into female burials in the period under consideration had similar semantics (Teterin, Mitko, Zhuravleva, 2010; Golovchenko, 2019). Vessels, as elements of funeral rites and rituals of abandonment of inhabited territories, are well known from the evidence from ritual complexes of various chronological periods (Tkachev, 2014; Sotnikova, 2015a, b).

Conclusions

The combination of “Scythian” and “Xiongnu” belt fittings in a single assemblage, and their use in the same ritual action of concealment, testify to the evolving practice of symbolic treatment of belt sets, which appeared at the sites of southern Siberia in the mid-1st millennium BC. Ritual treatment of belts, exemplified by their placement as ornaments into hoards, may also be identified along with destructive manipulations (unfastening the belt, symbolic breaking of ornaments, or use of defective items) observed in the evidence from the burials. Concealment of a large collection of belt fittings might have been a variation of the ritual of “abandoning the inventory”. In essence, it constituted sacrificing ornaments to the spirits of the area in order to ensure the well-being of seasonal or emergency migration.

Acknowledgment

The author expresses his gratitude to Dr. A.P. Borodovsky, the Leading Researcher of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the SB RAS, for the opportunity to work with the materials of the Iyus hoard.

Список литературы A Set of Clothing Items from the Iyus Hoard

- Beltikova G.V. 2002 Kulaiskiy klad s Barsovoy Gory. In Klady: Sostav, khronologiya, interpretatsiya. St. Petersburg: Izd. SPb. Gos. Univ., pp. 203-206.

- Beltikova G.V., Borzunov V.A. 2017 Unikalniy kulaiskiy klad v Surgutskom Priobye. Rossiyskaya arkheologiya, No. 4: 124-141.

- Bobrov V.V. 1979 O bronzovoy poyasnoy plastine iz tagarskogo kurgana. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, No. 1: 254-256.

- Bobrov V.V. 2002 Atributy shamanskogo kostyuma iz klada u sela Lebedi (Kuznetskaya kotlovina). In Klady: Sostav, khronologiya, interpretatsiya. St. Petersburg: Izd. SPb. Gos. Univ., pp. 206-212.

- Borodaev V.B. 1987 Novoobintsevskiy klad. In Pervobytnoye iskusstvo. Antropomorfniye izobrazheniya. Novosibirsk: IIFF SO AN SSSR, pp. 96-114.

- Borodovsky A.P. 2012 Datirovaniye mnogomogilnykh kurganov epokhi rannego zheleza Verkhnego Priobya yestestvennonauchnymi i traditsionnymi metodami (po materialam Bystrovskogo nekropolya). In Metody nauk o zemle i cheloveke v arkheologicheskikh issledovaniyakh. Novosibirsk: Izd. Novosib. Gos. Univ., pp. 344-392.

- Borodovsky A.P., Larichev V.E. 2011 Predmetniy kompleks Iyusskogo klada. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, Filologiya, vol. 11. No. 7: Arkheologiya i etnografiya: 196-208.

- Borodovsky A.P., Larichev V.E. 2013 Iyusskiy klad: (Katalog kollektsii). Novosibirsk: IAET SO RAN.

- Borodovsky A.P., Obolensky A.A., Babich V.V., Borisenko A.S., Mortsev N.K. 2005 Drevneye serebro Sibiri (kratkaya istoriya, sostav metalla, rudniye mestorozhdeniya). Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Borodovsky A.P., Oborin Y.V. 2018 Klady i tainiki bronzovykh predmetov s zheleznymi instrumentami gunno-sarmatskogo vremeni so Srednego Yeniseya. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, Filologiya, vol. 17. No. 7: Arkheologiya i etnografi ya: 86-98.

- Borodovsky A.P., Oborin Y.V. 2021 Kotly i klady Srednego Yeniseya epokhi rannego zheleza. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, Filologiya, vol. 20. No. 7: Arkheologiya i etnografi ya: 121-134.

- Borodovsky A.P., Troitskaya T.N. 1992 Burbinskiye nakhodki. Izvestiya SO RAN. Istoriya, fi lologiya i fi losofi ya, No. 3: 57-62.

- Burnakov V.A. 2012 Odezhda v obryadovoy praktike khakasskikh shamanov. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, Filologiya, vol. 11. No. 7: Arkheologiya i etnografi ya: 258-269.

- Cheremisin D.V., Zaporozhchenko A.V. 1996 “Pazyrykskiy shamanizm”: Artefakty i interpretatsii. In Zhrechestvo i shamanizm v skifskuyu epokhu: Materialy mezhdunar. konf. St. Petersburg: Izd. RGNF, pp. 30-32.

- Davydova A.V., Minyaev S.S. 1988 Poyas s bronzovymi blyashkami iz Dyrestuiskogo mogilnika. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, No. 4: 230-233.

- Davydova A.V., Minyaev S.S. 2008 Khudozhestvennaya bronza syunnu: Noviye otkrytiya v Rossii. St. Petersburg: GAMAS.

- Demin M.A., Sitnikov S.M. 1998 Arkheologicheskiye issledovaniya na pravom beregu Gilevskogo vodokhranilishcha. Sokhraneniye i izucheniye kulturnogo naslediya Altaiskogo kraya, iss. 9: 94-99.

- Devlet M.A. 1980 Sibirskiye poyasniye azhurniye plastiny II v. do n.e. - I v. n.e. Moscow: Nauka. (SAI; iss. D4-7).

- Dobzhansky V.N. 1990 Naborniye poyasa kochevnikov Azii. Novosibirsk: Novosib. Gos. Univ.

- Fedorova N.V., Gusev A.V., Podosenova Y.A. 2016 Gornoknyazevskiy klad. Kaliningrad: ROS-DOAFK.

- Frolov Y.V. 2000 O pryaslitsakh rannego zheleznogo veka Verkhnego Priobya kak kulturno-diagnostiruyushchem priznake. In Aktualniye voprosy istorii Sibiri. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 75-82.

- Golovchenko N.N. 2019 Voprosy interpretatsii kotlovidnykh podvesok naseleniya Verkhnego Priobya vtoroy poloviny I tys. do n.e. In Drevnost i Srednevekovye: Voprosy istorii i istoriografii: Materialy V Vseros. konf. studentov, aspirantov i molodykh uchenykh, Omsk, 12-13 oktyabrya 2018 g. Omsk: pp. 6-10.

- Golovchenko N.N. 2021 “No connection”: Rasstegnutyi poyas v pogrebalnoy obryadnosti naseleniya Verkhnego Priobya epokhi rannego zheleza. Narody i religii Yevrazii, No. 3 (26): 24-35.

- Golovchenko N.N., Besetaev B.B. 2021 Poleviye issledovaniya v Krutikhinskom rayone (itogi polevogo sezona 2021 goda). Poleviye issledovaniya v Verkhnem Priobye, Priirtyshye i na Altaye (arkheologiya, etnografi ya, ustnaya istoriya i muzeyevedeniye), No. 16: 82-86.

- Gordienko A.V. 2007 Raduzhny “hoard”. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 2: 63-74.

- Istoriya Altaya. 2019 Vol. 1: Drevneishaya epokha, drevnost i Srednevekovye. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Khavrin S.V. 2016 Metall epokhi khunnu mogilnika Terezin I (Tuva). Arkheologicheskiye vesti, No. 22: 105-107.

- Kilunovskaya M.E., Leus P.M. 2018 Noviye materialy ulug-khemskoy kultury v Tuve. Arkheologicheskiye vesti, No. 24: 125-152.

- Kuzmin N.Y. 2011 Pogrebalniye pamyatniki khunno-syanbiyskogo vremeni v stepyakh Srednego Yeniseya: Tesinskaya kulttura. St. Petersburg: Aising.

- Larichev V.E., Borodovsky A.P. 2006 Drevniye klady Yuzhnoy Sibiri. Nauka iz pervykh ruk, No. 2 (8): 52-65.

- Makarov N.P. 2013 Arkheologicheskiye klady iz fondov Krasnoyarskogo muzeya kak istochnik po mirovozzreniyu drevnikh i traditsionnykh obshchestv. In Integratsiya arkheologicheskikh i etnografi cheskikh issledovaniy, vol. 2. Irkutsk: Izd. Irkut. Gos. Univ., pp. 79-82.

- Martynov A.I. 1979 Lesostepnaya tagarskaya kultura. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Minyaev S.S. 2007 Dyrestuiskiy mogilnik St. Petersburg: Izd. SPb. Gos. Univ. (Arkheologicheskiye pamyatniki syunnu; iss. 3).

- Mogilnikov V.A. 1997 Naseleniye Verkhnego Priobya v seredine - vtoroy polovine I tysyacheletiya do n.e. Moscow: Nauka.

- Mogilnikov V.A., Umansky A.P. 1992 Kurgany Maslyakha-1 po raskopkam 1979 goda. In Voprosy arkheologii Altaya i Zapadnoy Sibiri epokhi metalla. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 69-93.

- Molodin V.I., Bobrov V.V., Ravnushkin V.N. 1980 Aidashinskaya peshchera. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Nashchekin N.V. 1967 Kosogolskiy klad. In Arkheologicheskiye otkrytia 1966 goda. Moscow: IA RAN, pp. 163-165.

- Nikolaev R.V. 1961 Yesaulskiy klad. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, No. 3: 281-284.

- Pletneva L.M. 2017 Oselki epokhi rannego zheleza iz dvukh muzeyev. Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogicheskogo universiteta, vol. 9 (186): 66-77.

- Podolsky M.P. 2002 Znamenskiy klad iz Khakasii. In Klady: Sostav, khronologiya, interpretatsiya. St. Petersburg: Izd. SPb. Gos. Univ., pp. 229-234.

- Pshenitsyna M.N., Khavrin S.V. 2015 Issledovaniye metalla klada liteishchika Ai-Dai (tesinskaya kultura). In Drevnyaya metallurgiya Sayano-Altaya i Vostochnoy Azii. Abakan: Ekhime, pp. 70-74.

- Savinov D.G. 2009 Minusinskaya provintsiya khunnu (po materialam arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy 1984-1989 gg.). St. Petersburg: Izd. SPb. Gos. Univ.

- Savinov D.G. 2012 Pamyatniki tagarskoy kultury Mogilnoy stepi (po rezultatam arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy 1986-1989 gg.). St. Petersburg: ElekSis.

- Shamshin A.B., Navrotsky P.I. 1986 Kurganniy mogilnik Rogozikha-1. In Skifskaya epokha Altaya. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 104-106.

- Shulga P.I. 2003 Mogilnik skifskogo vremeni Lokot-4a. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Shulga P.I. 2008 Snaryazheniye verkhovoy loshadi i voinskiye poyasa na Altaye, pt. 1. Barnaul: Azbuka.

- Shulga P.I., Umansky A.P., Mogilnikov V.A. 2009 Novotroitskiy nekropol. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Sotnikova S.V. 2015a Andronovskiye ritualniye kompleksy s perevernutymi sosudami: Sravnitelnaya kharakteristika i interpretatsiya. Problemy istorii, fi lologii, kultury, No. 3 (49): 231-245.

- Sotnikova S.V. 2015b Andronovskiye (fedorovskiye) pogrebeniya s perevernutymi sosudami: K rekonstruktsii predstavlenii o roli zhenshchiny v miforitualnoy praktike. In Arkheologiya Zapadnoy Sibiri i Altaya: Opyt mezhdistsiplinarnykh issledovaniy. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 267-272.

- Spitsyn A.A. 1906 Shamanskiye izobrazheniya. In Zapiski Otdeleniya russkoy i slavyanskoy arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obshchestva, vol. 8 (1). St. Petersburg: pp. 29-145.

- Teterin Y.V. 1995 Poyasniye nabory gunno-sarmatskoy epokhi Gornogo Altaya. In Problemy okhrany, izucheniya i ispolzovaniya kulturnogo naslediya Altaya. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 131-135.

- Teterin Y.V. 2012 Poyasniye podveski Yuzhnoy Sibiri pozdneskifskogo vremeni. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, Filologiya, vol. 11. No. 7: Arkheologiya i etnografi ya: 117-124.

- Teterin Y.V. 2015 Poyasniye podveski khunnskoy epokhi Yuzhnoy Sibiri. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, Filologiya, vol. 14. No. 5: Arkheologiya i etnografi ya: 51-60.

- Teterin Y.V., Mitko O.A., Zhuravleva E.A. 2010 Bronzoviye miniatyurniye podveski-sosudy Yuzhnoy Sibiri. Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, Filologiya, vol. 9. No. 7: Arkheologiya i etnografi ya: 80-94.

- Tkachev A.A. 2014 Keramika v ritualnoy praktike naseleniya pakhomovskoy kultury. In Trudy IV (XX) Vseros. arkheol. syezda v Kazani. Kazan: Otechestvo, pp. 665-668.

- Zykov A.P., Fedorova N.V. 2001 Kholmogorskiy klad. Kollektsiya drevnostey III-IV vv. Yekaterinburg: Sokrat.