A study of Bronze age ceramics from the forest zone of Eastern Europe: what does the term “Fatyanovo-like” mean?

Автор: Volkova E.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145366

IDR: 145145366 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2018.46.2.052-059

Текст статьи A study of Bronze age ceramics from the forest zone of Eastern Europe: what does the term “Fatyanovo-like” mean?

Problem statement

The term “Fatyanovo-like” was introduced for the first time, probably, by A.A. Spitsyn, for ceramics similar to the Fatyanovo (in terms of their shapes, ornamentation, and technology), though not identical to them (Voss, 1952: 190). It related mainly to ornamentation and shape of pottery, and partially to the technological features observed visually. Such features as thin sherds, well-washed clay, and sand admixture were noted for Fatyanovo and Balanovo ceramics, while coarse sherds, vegetable and shell admixtures were typical for the Volosovo tradition. M.E. Voss explained the appearance of Fatyanovo-like ceramics by contacts between the Fatyanovo and local people (Ibid.: 188–191). N.N. Gurina considered such ceramics Fatyanovo household ware (1963:

196–197). It was only thanks to the studies conducted by I.V. Gavrilova and O.S. Gadzyatskaya that the “Fatyanovo-like ceramics” term started acquiring a strictly scientific rationale. Having studied materials from various districts of the Upper Volga region, both researchers came to the conclusion that the Fatyanovo-like ceramics had appeared as a result of contacts between the Fatyanovo and local populations that were different in different districts (Gavrilova, 1983; Gadzyatskaya, 1992). In view of this, Gadzyatskaya offered distinguishing cultures with the Fatyanovo-like ceramics (1992: 139).

For this study, materials from the Nikolo-Perevoz I and II sites, which contain large amounts of both Fatyanovo and Fatyanovo-like ceramics, proved to be very promising. Their analysis makes it possible to answer the following questions: what are the

Fatyanovo-like ceramics, and what historical and cultural phenomena do they reflect?

Materials

The Nikolo-Perevoz I Neolithic settlement (the Taldomsky District of the Moscow Region) was discovered and excavated by B.S. Zhukov in 1934. Since 1958, the site has been studied by the expedition of the State Historical Museum, under the supervision of V.M. Rauschenbach. In 1962, slightly northwards, the Nikolo-Perevoz II settlement was discovered. Both sites are stratified, with partially mixed layers of the Upper Volga, Lyalovo, Volosovo, Fatyanovo, and Dyakovo cultures. Among other artifacts, Fatyanovo-like ceramics were found there in abundance.

In 1958, a collective burial was discovered at the Nikolo-Perevoz I site. Rauschenbach identified it as a Fatyanovo burial and dated it no earlier than the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. Nine skeletons lay in the burial pit of 3.4 × 2.5 m in size. Three of them were identified as a female, a child, and a male (as determined by M.M. Gerasimov). Six dead bodies were laid with their heads towards the south-west, and three towards the north-east; one was in an extended supine position, and the remainder were buried in a flexed position on their sides. In the vicinity of the spines of three skeletons, Volosovo flint arrowheads were found. Grave goods included five clay vessels (including a small cup), two stone perforated axehammers, five flint arrowheads, and a dart. According to Rauschenbach (1960), the presence of Fatyanovo people at the settlement was temporary, and they were enemies of the aborigines, as evidenced by the collective burial of Fatyanovo people who died in a battle or as a result of epidemics.

O.N. Bader and A.K. Khalikov, challenging the attribution of the burial to the Fatyanovo culture, considered it a Balanovo site “with a typically Osh-Pando complex” (1976: 80), which is dated to the 13th to 12th centuries BC. As opposed to Bader and Khalikov, B.S. Soloviev (2007: 27) reasons that mixture of the Balanovo and Atlikasy tribes resulted in the appearance of the “syncretic Balanovo/ Atlikasy and Osh-Pando/Khula-Syuch complexes”*. Thus, the cultural affiliation of the burial remains controversial.

Analysis of pottery traditions based on ceramics from the burial

In order to determine the cultural affiliation of the burial, a task was set to distinguish the Fatyanovo-like ceramics from the entire pottery collection of the Nikolo-Perevoz I and II sites, and to trace their origin. Among the five vessels found in the burial, only four (No. 1–3, 5) proved to be accessible for immediate analysis*.

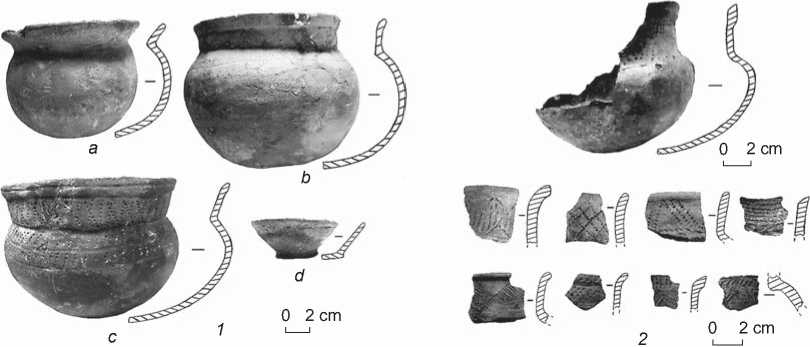

Vessel No. 1 is an undecorated round-bottomed pot with a globe-shaped body and a short neck strongly expanding towards the mouth (Fig. 1, 1 , a ); made of highly ferruginous clay with medium sand content, to which squeeze of dung and coarse broken stone were added.

Vessel No. 2 is also a round-bottomed pot with a globe-shaped body, but it has a straight neck with an everted rim (Fig. 1, 1 , b ). An incised pattern was applied by a tool with an obtuse working edge, which left rather wide grooves. A horizontal zigzag extends across the entire neck. The second ornamental zone is located on the shoulder, and consists of a “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines”. Ornamental zones are defined by straight lines made by various tools: a cord imprint can be seen at the joints of the neck with the shoulder, while the second line is drawn by a tool that was used for the remaining ornament on the vessel. The bottom portion is unornamented. The pottery paste is the same as that of vessel No. 1.

Vessel No. 3 is a round-bottomed pot with a globeshaped body and a straight neck (Fig. 1, 1 , c ). The vessel is ornamented with a comb stamp and an incising tool with a rounded working edge of the same type as in the case of vessel No. 2. A horizontal straight line is incised along the rim. A lattice interrupted by parallel variably-inclined lines within a small (5 cm) area is applied onto the neck with a comb stamp. Two ornamental zones filled with a “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” are located on the shoulder and slightly below it. The lines are also made with a comb stamp. The rows are separated by an incised straight line, and the same line defines the lower ornamental zone. The bottom portion is unornamented. The vessel is made of clay with high sand content, to which squeeze of dung and coarse grog and broken stone were added.

Vessel No. 4 , judging by the description and the photograph, is a round-bottomed pot with a globe-

*The author’s special thanks go to B.S. Soloviev for the submitted materials, and also substantial assistance in working with collections.

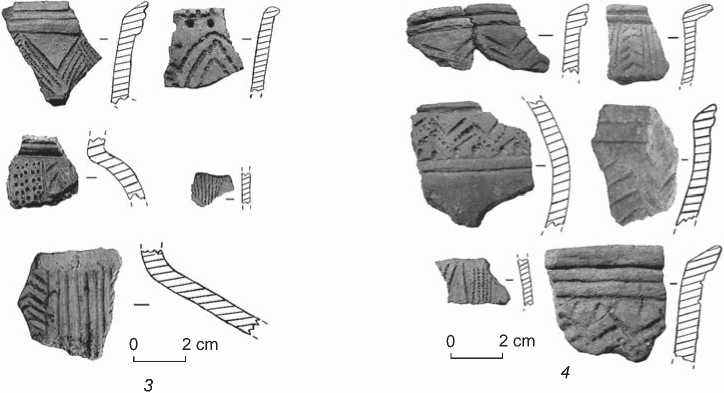

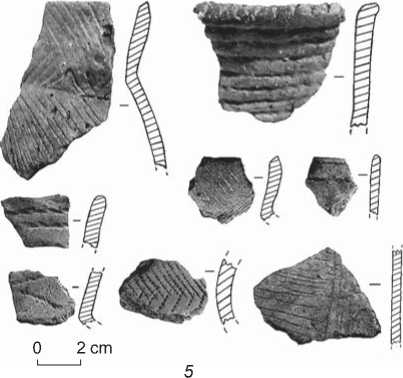

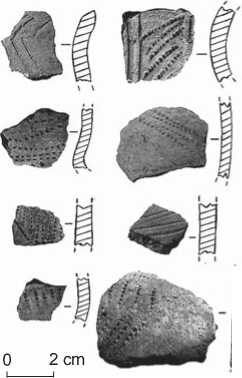

Fig. 1. Ceramics from Nikolo-Perevoz I and II.

1 – vessels from the burial; 2 – Fatyanovo ceramics from the settlements; 3 – 6 – ceramics of Fatyanovo-like groups 1 ( 3 , 4 ), 2 ( 5 ), and 3 ( 6 ).

ж$шжж

shaped body, “a shortened neck and a more strongly everted rim” (Rauschenbach, 1960: 32–34, fig. 3, 8 ). The vessel is ornamented with a tool having a rounded working edge, which left small and shallow depressions. Two horizontal rows of vertical or oblique lines were applied with this tool on the vessel’s neck, and one row on the vessel’s shoulder. The bottom is unornamented.

Vessel No. 5 is a small unornamented cup on a tray (Fig. 1, 1 , d ). The pottery paste is similar to the above; however, the grog and broken stone are average-sized.

Comparative analysis of ceramics from the burial and ceramic assemblages of the Fatyanovo culture in general and of its Moscow local group, the data on which were obtained earlier (Volkova, 1996: 84–114), has demonstrated a number of differences between the pottery traditions. First, no cups with trays (vessel No. 5) have been found in the Fatyanovo culture so far, and vessels with strongly expanding necks (vessel No. 1) and everted rims (vessels No. 2 and 4) are not typical of this culture either. Second, the horizontal zigzag on vessel No. 2 is made in a manner uncharacteristic of the Fatyanovo tradition. Usually on Fatyanovo ceramics, in the case that this pattern occupied the entire ornamental zone, the zigzag size was not increased, but several rows of small zigzag were drawn instead. The pattern of the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” on vessel No. 2 shows strongly scattered and long lines, which is also untypical of the Fatyanovo ceramics. Fatyanovo people did not draw a horizontal straight line along the rim (vessel No. 3). Ornamental patterns made by shallow pits (vessel No. 4) are rare in the Fatyanovo ceramics. Third, two different technological traditions, widespread among the Fatyanovo population, have been recorded on the vessels from the burial: 1) manufacture of vessels from clay with high sand content, to which squeeze of dung, grog, and broken stone were added (vessels No. 3 and 5); 2) use of highly ferruginous clay with medium sand content, to which squeeze of dung and broken stone were added (vessels No. 1 and 2).

Thus, the ceramic assemblage from the burial at Nikolo-Perevoz I shows a number of deviations from the pottery traditions of both the Fatyanovo culture as a whole and from its Moscow local group.

Fatyanovo-like pottery traditions

To which population do the revealed traditions, alien to the Fatyanovo people, belong? To answer this question, “Fatyanovo” ceramics from the Nikolo-Perevoz I and II settlements were subjected to special technological and morphological analysis. First, the whole assemblage was divided, according to the ornamental traditions, into Fatyanovo proper (fragments of 87 vessels; Fig. 1, 2) and Fatyanovo-like (fragments of 42 vessels) ceramics, after which, the latter type was divided into three groups by special features of the pottery paste recipes and, partially, ornamentation.

Fatyanovo-like group 1 includes fragments of 23 vessels (Fig. 1, 3 , 4 ), in which the Fatyanovo traditions combine with the Osh-Pando ones. The latter include: 1) an ornamental pattern of “horizontal straight line” on the vessel’s rim, represented by a sufficiently wide groove instead of the thin line traditional for the Fatyanovo ceramics; 2) the presence of similar vertical grooves on the vessel; 3) elongated triangles cross-hatched in a particular way; 4) a combination of ornamenting tools, untypical of the Fatyanovo culture (the same vessel contains elements made by comb and plain stamps, and also by a small blunt tool that was used to incise grooves and make depressions). The paste of these vessels is represented by three recipes, widespread among the Fatyanovo people.

Fatyanovo-like group 2, where the Fatyanovo traditions combine with the Volosovo ones, includes fragments of 11 vessels (Fig. 1, 5 ). These show, first, the ornamental pattern of “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” along the rim edge and, second, the main element of this pattern usually twice as long as the traditional Fatyanovo one; i.e. the ornamenting tool had a longer working edge. Also, this group is distinguished by a specific composition of pottery paste: bird-dung were added to it instead of the squeeze of dung traditional for the Fatyanovo ceramics.

Fatyanovo-like group 3 consists of ceramics in which the Fatyanovo traditions combine with those of a population of uncertain origin (Fig. 1, 6 ). Fragments of eight vessels are assigned to this group. They differ from the Fatyanovo vessels, first, in the presence of ornaments applied with a long comb stamp; second, in non-traditional execution of patterns of “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” and “horizontal zigzag”; and, third, in the use of both plain and comb stamps for the same vessel. Sometimes, wet dung was added to the paste instead of squeeze of dung. Other components are similar to the Fatyanovo.

Notably, all three groups are dominated exactly by the Fatyanovo traditions. These are Fatyanovo ornamental patterns, and two- or three-part recipes of pottery paste, including organics, grog, and broken stone. As for the shapes of vessels, the presence of vessels with high straight necks should be noted in all three groups.

Comparative analysis of Fatyanovo and Fatyanovo-like pottery traditions

The Fatyanovo-like groups were compared with vessels from the burial, with Fatyanovo ceramics from the settlements, and with ware of the Moscow local group belonging to this culture, with respect to those pottery traditions which were recorded during analysis*. At the qualitative level, the pottery traditions have been revealed and their degree of expansion has been assessed, while at the quantitative level, the similarity coefficient (SC) between all the identified groups of ceramics has been calculated for individual stages of the pottery production and for stylistic ornamental levels (see the similarity coefficient calculation procedure in (Volkova, 2010: 93)).

Kinds of clay . For ceramics from the burial, the use of clay with medium and high sand content in equal proportions (by 50 %) is recorded. Paste for the Fatyanovo ware predominantly (79 %) represented clay with high sand content and much more rarely with medium (13 %) and low (8 %) sand content. For the Fatyanovo-like groups, predominance of clay with high sand content was recorded (group 1 – 70 %, 2 – 82 %, 3 – 63 %). However, group 1 contains ceramics made of clay with low sand content (17 %), no sand content (9 %), and medium sand content (4 %), group 2 with medium sand content (18 %), and group 3 with low (25 %) and medium sand content (13 %). The Moscow local Fatyanovo group is characterized by the use of clay with medium sand content (95 %). In terms of their degree of similarity, ceramics from the burial are closest to Fatyanovo-like group 2 (SC = 68 %).

Pottery paste composition. It will be recalled that two recipes (50 % each) have been recorded for the ceramics from the burial: clay + squeeze of dung + + broken stone, and clay + squeeze of dung + grog + + broken stone. The Fatyanovo ceramic assemblage is also characterized by adding squeeze of dung, which is present in all pastes; apart from that, grog (43 %), grog and broken stone (37 %), and more rarely broken stone (18 %) were added. In individual cases, paste was composed only of clay and squeeze of dung (2 %). In Fatyanovo-like group 1, four recipes were recorded, wherein, apart from clay and squeeze of dung, grog + + broken stone (35 %), broken stone (36 %), grog (22 %), and sand (9 %) were present. The greatest diversity of recipes was observed in Fatyanovo-like group 2. Among these, clay + bird-dung (27 %) and clay + + bird-dung + broken stone (27 %) are most abundant, while other variants (clay + squeeze of dung + broken stone, clay + squeeze of dung + grog, clay + bird-dung + + grog, clay + bird-dung + grog + broken stone) have only been encountered in one or two vessels each. In Fatyanovo-like group 3, five recipes were recorded: clay + squeeze of dung + grog (25 %), the same + + broken stone (25 %), clay + squeeze of dung + broken stone (25 %), clay + squeeze of dung (12 %), and clay + + dung + grog (12 %). For the Moscow-group ceramics, the presence of squeeze of dung in all pastes has been observed. Furthermore, grog (61 %), more rarely broken stone (18 %), and grog and broken stone (18 %) were added. In individual cases, the clay + squeeze of dung recipe was encountered (2 %). In terms of the similarity of pottery paste traditions, ceramics from the burial are closest to Fatyanovo-like group 1 (SC = 86 %).

Ornamenting tools . The use of four types of ornamenting tool has been recorded for ceramics from the burial, though an incising tool was used most frequently (67 %). In the Fatyanovo complex, the use of four types of ornamenting tools has also been revealed. Among them, a comb stamp (72 %) and an incising tool (29 %) prevail. In Fatyanovo-like group 1, ornaments were applied with five different ornamenting tools. Most frequently, an incising tool (65 %), comb (52 %), and plain (30 %) stamps were used. The use of five ornamenting tools has also been recorded for Fatyanovo group 2. An incising tool (44 %) and a comb stamp (33 %) prevail. In Fatyanovo-like group 3, ornaments were applied with four different tools, though a comb stamp (75 %) was most popular. For the Moscow local group, the use of four types of ornamenting tools has been recorded. A comb stamp (55 %) is most common, but an incising knife (38 %) and cord (30 %) were also frequently enough. In terms of the ornamenting tools, the ceramics show considerable resemblance to Fatyanovo-like groups 2 (SC = 81 %) and 1 (SC = 74 %).

Stylistic analysis of ornamental traditions. It will be recalled that I have distinguished three ornamental elements in the Fatyanovo ceramics (Volkova, 2010: 99): a point, a short straight line, and a long straight line. All of them are present on the vessels from the burial, though long and short lines prevail (67 % each). The Fatyanovo ceramics from the settlements do not have the “point” element, while the short straight line (81 %) dominates over the long one (29 %). In the Fatyanovo-like groups, all three elements were used. In group 1, the short (83 %) and long (65 %) straight lines dominate over the point

(19 %), while in group 2, the long straight line (67 %) dominates over the short line (44 %) and the point (11 %). In Fatyanovo-like group 3, the short straight line (88 %) prevails. In the Moscow group ceramics, this element dominates over the long straight line (75 % against 58 %). In terms of the degree of similarity of the ornamental element, ceramics from the burial are closest to Fatyanovo-like group 1 (SC = 91 %).

On the vessels from the burial, five ornamental patterns have been distinguished, among which the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (100 %) and “horizontal straight line” (67 %) prevail. On Fatyanovo ceramics, 12 patterns have been recorded. Three of these are popular: the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (54 %), “horizontal straight line” (34 %), and “parallel variably-inclined lines” (36 %). In Fatyanovo-like group 1, nine ornamental patterns are represented, among which the “horizontal straight line” (43 %) and the “vertical herring-bone” (26 %) are most common. In Fatyanovo-like group 2, only four patterns have been recorded. The “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (67 %) and “horizontal straight line” (78 %) prevail. The same patterns are widespread (43 % each) in Fatyanovo-like group 3, where only three patterns are represented. Moscow local group ceramics has revealed 11 ornamental patterns, among which the “horizontal straight line” (92 %) absolutely prevails, the “lattice” (61 %) and the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (57 %) are very frequent, and the “parallel variably-inclined lines” (39 %) is also rather widespread. Notably, the patterns of “contoured rhomboid” and “lattice” are absent in all Fatyanovo-like groups. In terms of the composition and the prevalence of ornamental patterns, the ceramics from the burial proved to be closest to Fatyanovo-like groups 3 (SC = 64 %) and 2 (SC = 63 %). But it should be noted that vessels from the burial and Fatyanovo-like group 1 stand out from the others by the presence of horizontal straight line on their rims.

Four ornamental patterns are widespread in almost all the distinguished groups of ceramics: “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines”, “horizontal straight line”, “horizontal zigzag”, and “parallel variably-inclined lines”. However in various groups they were used on vessels in different motifs*. For example, the ceramics from the burial have the patterns of “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” and “horizontal zigzag” only in the main motif, and the “horizontal straight line” in the supplementary one. The pattern of “parallel variably-inclined lines” is applied only in a single row. In Fatyanovo ceramics from the settlements, the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (78 %) and “horizontal straight line” (96 %) are most frequently encountered in the supplementary motif, the “horizontal zigzag” is represented exclusively in the main motif, while the “parallel variably-inclined lines” are applied only in a single row. Fatyanovo-like group 1 is characterized by the use of the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (100 %) and “horizontal straight line” (96 %) in supplementary motifs, while the “horizontal zigzag” in the main one. The pattern of “parallel variably-inclined line” has not been recorded here at all. On the contrary, Fatyanovo-like group 2, is dominated by the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (67 %) and “horizontal straight line” (57 %) in the main motif. The “horizontal zigzag” is absent here, while the “parallel variably-inclined lines” are applied only in a single row. In Fatyanovo-like group 3, the pattern of “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” is included only in the main motif (100 %), the “parallel variably-inclined lines” are applied in a single row, while two remaining patterns are absent. The use of the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” (71 %), “horizontal straight line” (74 %), and “horizontal zigzag” (55 %) patterns is typical for Fatyanovo Moscow local group ceramics mainly in the supplementary motif. In the majority of cases (95 %), the pattern of “parallel variably-inclined lines” was applied in a single row.

Only motifs of the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” vary widely in various ceramic assemblages. In ceramics from the burial and Fatyanovo-like groups 2 and 3, this pattern is used in the main motif; whereas in the Fatyanovo complex and in Fatyanovo-like group 1, in contrast, it is employed in the supplementary one. The ceramic groups under study do not differ in the motifs of “parallel variably-inclined lines” pattern. Meanwhile, the pattern of “horizontal zigzag” is used in the main motif in all groups of ceramics, apart from the Moscow local group.

In terms of the “horizontal row of vertical or oblique lines” pattern motifs, the vessels from the burial are closest to Fatyanovo-like group 3 (SC = 75 %), and in terms of the “horizontal zigzag” and “horizontal straight line” pattern motifs to Fatyanovo ceramics (SC = 100 and 96 %, respectively) and Fatyanovo-like

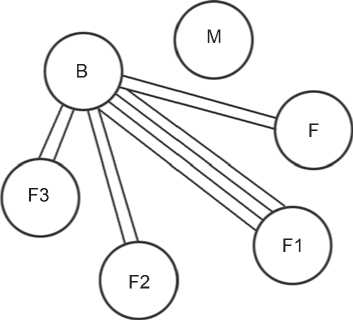

Fig. 2. Graph of connections of the ceramics from the burial with other ceramic groups.

B – vessels from the burial, M – ceramics of the Moscow local group, F – Fatyanovo ceramics from the settlements, F1–F3 – Fatyanovo-like groups.

group 1 (SC = 100 and 90 %). Judging by the maximum degree of similarity, a graph of connections of the ceramics from the burial with other ceramic groups was plotted (Fig. 2), wherein one line corresponds to each high similarity coefficient. It demonstrates dominant connections with Fatyanovo-like group 1, and complete absence of such connections with the Moscow local group ceramics.

Conclusions

The results of analysis of the ceramics from Nikolo-Perevoz I and II settlements and from the collective burial enable the following conclusions to be drawn. First, it should be noted that the collective burial at Nikolo-Perevoz I demonstrates considerable deviations from the main funerary traditions of the Fatyanovo population (for more detailed information about these traditions see (Volkova, 2010: 81–85)). This applies primarily to the grave goods. In all double and two collective Fatyanovo burials (the Bolshnevo II cemetery), they lay strictly at certain places in the vicinity of each buried person (near the feet, head, or waist). Further, performance of funerals at the place of settlement was not typical of the Fatyanovo people, while among the Volosovo population it was a sustained tradition (Kraynov, 1987: 23). Possibly, this is a manifestation of mixing the Fatyanovo and Volosovo funerary rites.

Second, ceramics from the burial show mainly mixed Fatyanovo-like pottery traditions, but not Fatyanovo. In terms of pottery paste recipes, they are similar to Fatyanovo-like group 1, in terms of the used ornamenting tools to groups 1 and 2, in terms of the ornamental elements to group 1, in terms of the ornamental patterns to groups 2 and 3, and in terms of the motifs of ornamental patterns to Fatyanovo ceramics and to Fatyanovo-like groups 1 and 2. Quantitative analysis of the degree of similarity in technological and ornamental traditions, and distinguishing the strongest connections, clearly demonstrate the greatest similarity between ceramics from the burial and Fatyanovo-like group 1. This brings us to the conclusions that these ceramics and, consequently, the burial itself, were left by a population with mixed Fatyanovo-Osh-Pando pottery traditions; possibly with the participation of a population with mixed Fatyanovo-Volosovo traditions.

Third, there is every reason to suppose that Fatyanovo group 2 was developed on a local basis, since the site contains both Volosovo and Fatyanovo ceramics. Conversely, Fatyanovo-like group 1 appeared here, most probably already in a fully developed form, i.e. mixing of the Fatyanovo and Osh-Pando populations took place outside of this settlement. This is evidenced by the absence of typical Osh-Pando ceramics with a sustainable recipe of paste (clay + squeeze of dung + grog) at the site. Apparently, when advancing from east to west, the Osh-Pando people mixed with the related Fatyanovo population, which resulted in the formation of Fatyanovo-like group 1, which is characterized by individual Osh-Pando ornamental patterns and Fatyanovo recipes of pottery paste, such as clay + squeeze of dung + broken stone and clay + squeeze of dung + grog + broken stone, wherein broken stone is recorded even in grog, which points to a sustainable tradition of its use.

Fourth, development of Fatyanovo-like group 3 could also have taken place at the settlement. It could well have happened that this process, in addition to the Fatyanovo people, involved participation of the population that left ceramics that I have called “Bronze Age ceramics”. However, their culture has not so far been identified.

Thus, I suppose that a small group of Fatyanovo people came to Volosovo settlements; they not only lived amicably together with the local people, but also entered into marital relations with them, which resulted in the formation of mixed Fatyanovo-Volosovo pottery traditions. Possibly, a little bit later, a group of mixed Fatyanovo-Osh-Pando people, to whom the collective burial at Nikolo-Perevoz I belongs, also came here.

Finally, it should be noted that the conclusions drawn have a certain methodological importance. Since special features of the so called Fatyanovo ceramics depend in all cases on the population groups that participated in mixing with the Fatyanovo people, the use of umbrella term “Fatyanovo-like ceramics” is improper, as I see it. In addition, when societies at different levels of social and economic development (such as, for example, the Fatyanovo and Volosovo people) are mixed, the results of mixing pottery traditions are more impressive than in the case of societies with approximately the same level (such as the Fatyanovo and Osh-Pando people). This phenomenon is typical of ancient ethnocultural history. Processes of mixing between various groups of Andronovo population of the Northern Kazakhstan and local groups of the southwestern Siberia may serve as an example.