An early Jurchen text among rock representations near the Arkhara river in the Amur basin (history, research results, and new evidence)

Автор: Zabiyako A.P.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145451

IDR: 145145451 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.3.094-103

Текст статьи An early Jurchen text among rock representations near the Arkhara river in the Amur basin (history, research results, and new evidence)

Information about the written characters on the rocks was first published by the Russian explorers of Siberia Nikolai Spathari (late 17th century), Ph.J. von Strahlenberg, P.S. Pallas, G.F. Miller, and others (18th century) (Spathari, 1882: 85; von Strahlenberg, 1730: Tab. VII, XI–XII; Pallas, 1786: 474; Miller, 1999: 519– 533). In the early 19th century, a great contribution to the study of “letters and inscriptions” on stones was made by G.I. Spassky. He drew attention to the fact that these written characters resembled “Mongolian and Tatar” letters and the “Manchu script”, and their sources and parallels should not be sought in European types of letters, but “in Oriental ancient and new letters” (Spassky, 1818: 80). The studies of A.P. Okladnikov on the territories close to the Amur region have great importance for the topic of our article. Okladnikov discovered rock characters similar in type to the old Mongolian script or representing an “imitation of runic letters” (see, e.g., (Okladnikov, Zaporozhskaya, 1970: 165)). Fragments of written characters on these territories were also found by A.V. Tivanenko (see, e.g., (Tivanenko, 2011)).

Thus, characters written next to rock representations are a fairly common and well-studied phenomenon in North and Central Asia. In the Far East, in the basin of the Amur River, they are extremely rare.

This article presents information about a written text discovered in 2003 at the archaeological site of Arkharinskaya Pisanitsa (Arkhara rock art site). The research is based on the author’s field materials gathered

during the expeditions in 2003 and in 2014–2018. During the field work, the rock representations were documented by contact and non-contact methods: they were drawn on plastic film, copied on paper, and were photographed in various digital formats, including RAW. In the laboratory, digital copies were processed using image-editing software. Written characters on the rock were interpreted following traditional methods of source and textual analysis, as well as semiotics.

Research history

The archaeological monument of the Arkhara rock art site is located on the right bank of the Arkhara River, 48 km upstream of the village of Gribovka, and 97 km upstream of the confluence of the Arkhara and Amur rivers (Fig. 1). Rock signs were written on granite outcrops of the hillside, which steeply descend to the river. The height of the rock outcrops was about 10 m in its upper part, from which the stone wall gradually decreased in height in both directions. The length of the outcrop was about 50 m; surfaces with representations were located on a section 30 m long at a height ranging from 2 to 8 m. The signs were made with red paint (ocher) of various shades and black paint (Fig. 2).

Rock representations had been known to Russian dwellers since they had settled along the banks of the river in the second half of the 19th century. The first rock representations at the Arkhara were described by Saenko (unfortunately, his initials are unknown) in a brief (half page) note (1930). The first scholarly description

Fig. 1 . Map showing the location of the Arkhara rock art site.

of the site was given by V.E. Larichev, who examined the petroglyphs during the Far Eastern Archaeological Expedition of 1954, directed by Okladnikov. The survey results are presented in a most complete form in the expedition journal (Okladnikov, Larichev, 1999). Larichev, at that time a student at the Department of the History of China at the Oriental Faculty of the Leningrad State University, noticed several written characters, which he interpreted as Chinese, among a large number of figurative and non-figurative images, including characters written in “dark paint” (black? – A.Z. ): “the

Fig. 2 . The Arkhara rock art site. General view. Photo from a drone. 2017.

Chinese character byen for ‘wood’” ( ben 本 ‘tree trunk, root’ or mu 木 ‘tree’. – A.Z. ) and “2 rows of Chinese characters” written in “black ink, cursive script, and not very clearly”. Among the latter, Larichev could discern only the character “mountain” ( shan 山 . – A.Z. ) (Ibid.: 26). The images were not reproduced and information about them did not appear in publications by the members of the expedition of 1954.

In 1968, A.I. Mazin continued to work at the site. He recorded, described, and first published most of the images. In total, he identified 360 images painted on the rock with “red or light red ocher”, which were “homogeneous” in style and time of creation (Mazin, 1986: 82–95). In that publication, as in his other studies, Mazin did not mention any written characters.

A new stage in the study of the site began in 2003. In August, 2003, the author of this article together with an employee of the Amur State University (hereafter AmSU) R.A. Kobyzov surveyed the site. All petroglyphs available for examination were recorded on photo and video; some of the images were sketched and traced on paper. The entire array of petroglyphs was divided according to the principle of color classification into two groups—“red” and “black” signs. Both groups included signs, which differed not only in form, but also in their essential features. The presence of essentially different signs on the rock predetermined the structuring of all images into two types: ideograms and characters. The concept of the ideogram has been quite often used for describing rock representations (Leroi-Gourhan, 2009: 260–263; 274–275; and others). We should note that we interpret the term ideogram in a broader sense than A. Leroi-Gourhan did. An ideogram is a conventional graphic sign—a symbol representing a concept or idea of an object in visual form. Each ideogram contains a special meaning and can function separately from other ideograms, and thus it may not belong to a language. Accordingly, the ideogrammatic signs are not connected by linear relationships into a specific order and do not form an ordered semantic system that codifies a statement. Figurative and non-figurative representations act as ideograms in the context of the study of petroglyphs. It is important that ideograms are not a script in the strict meaning of this term. Leroi-Gourhan drew attention to this fact: “Paleolithic representations cannot be viewed as signs of ‘pre-writing’… in order to be such, they have to constitute a linearly organized assemblage of symbols. However, the Paleolithic representations in the first links of the chain are important for clarifying the first attempts at speech transmission” (Ibid.: 260).

Several types of scripts are known. One of them (pictorial script) is the most relevant for our discussion. Pictorial characters are conventional signs, graphic elements of writing as a way of visualizing language and speech.

In the study of the Arkhara rock art site, we are dealing with representations that belong to the types of ideogrammatic signs and hieroglyphic signs. Both types were identified already when examining the “red” and “black” images in 2003.

Hieroglyphic characters (graphemes) constitute a small, yet very important part of the group of “red” images, but prevail in the group of “black” images. Going back to the records of Larichev, we may observe that the Chinese character mentioned by him in the journal, read as ben with the meaning of ‘tree’ (as indicated by the author) has not been found in dictionaries of the Chinese language. Since Larichev did not provide the graphic form of the character in his journal, it may be assumed that he had in mind either the character ben 本 (the exact meaning ‘root, foundation, base, firm law, unchangeable norm, source, beginning, antiquity, nature, paternal clan, ancestors, direct descendants, gratefulness to the ancestors; homeland, native places; family name Ben’ (Bolshoy kitaisko-russkiy slovar…, 1984: 741–744)), or character 木 similar in graphic form, the first and main meaning of which is ‘tree’ (Ibid.: 699–701). We did not find a character in the form of 本 or 木 on the rock, but we identified a character with graphic form somewhat between the Chinese characters ben 本 and mu 木 : as opposed to the character mu , it has a lower horizontal line. However, unlike the character ben , the horizontal line does not intersect the vertical line, but is located at its base. We could not find such a character in large dictionaries of Chinese characters. It is possible that either this character was written on the rock without following the rules of calligraphy (in this case, it is a variant of the character mu or ben ), or does not belong to the Chinese script at all (Fig. 3).

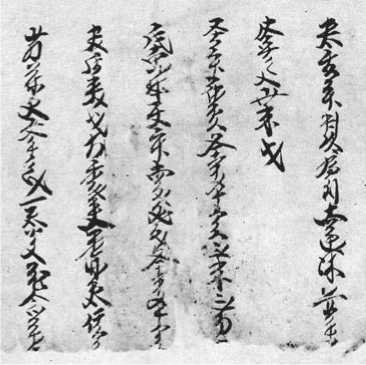

No images have been found on the rock that, according to the journal, made up “2 rows of Chinese characters” written in “black ink, cursive script, and not very clearly (only the character ‘mountain’ – shan, was clear)” and appeared “in the central part where the representations were most densely located” (Okladnikov, Larichev, 1999: 26). They may have been lost since the time of their inspection in 1954. However, there are graphemes of a different configuration. In 2003, 24 graphemes written in black paint (ink) that form a coherent whole consisting of three vertical columns or rows, were identified on one of the stone surfaces to the right of the center. The area of the characters was 15 × 25 cm. The size of each graphic element on average was 2 × 2 cm. There were seven characters in the right column, ten characters in the central column, and seven characters in the left column (Fig. 4). The paint was applied to the surface with a brush.

Already at the stage of visual examination, it was obvious that the images organized in a linear composition represented a kind of writing with hieroglyphic characters, and constituted a complete text. Judging by the execution technique, the graphemes were written by the hand of a skilled artisan who could confidently write in some style of hieroglyphic script.

The main problem was to establish the type of hieroglyphic writing, and to translate the text. Already in the first publication on this inscription, it was argued that the text could have belonged to the Khitan or Jurchen scripts, but most likely to the Jurchen script (Zabiyako, Kobyzov, 2004: 133).

Our research approach was based on the following points. The graphemes were drawn over petroglyphs that had been painted with ocher. The petroglyphs depicted in red paint (ocher) belong to the Early Iron Age–Early Middle Ages. The “black” graphemes could not be earlier than the red-painted petroglyphs and thus earlier than the Middle Ages. Notably, the inscription is patinated— covered with “rock varnish”, which emerges over the paint layer a fairly long time after the paint is applied. Accordingly, the inscription could not have been made in the Late Middle Ages, and the age of the characters should be about 800–1000 years.

At that time, hieroglyphic writing of three types (Chinese, Khitan, and Jurchen) could have been used in the Amur region. Chinese characters were excluded from consideration owing to dissimilarity with the characters of the Arkhara inscription. The use of the Khitan script is unlikely. In the 10th century, a significant part of the Amur region became included in the Khitan sphere of influence. The Khitan people were a Mongol-speaking ethnic group that created the Liao Empire (907–1125) in the east of Asia. The Khitan large script was created in the Khitan State in 920, and Khitan small script was created ca 925. The graphic features of both types of Khitan scripts were based on Chinese characters (Terentiev-Katansky, 1990: 68–70; Zaitsev, 2011: 146–147). However, the Khitan people did not leave any obvious traces of statehood, with which writing is usually associated, on the left bank of the Upper and Middle Amur region.

The ethnic core of the Jurchen people emerged in Northeast China. In about the 9th century, some Jurchen groups migrated to the banks of the Amur River, where by the end of the 10th–early 11th century, they created the highly advanced culture of the Amur Jurchen people. In the Amur region, the Jurchen people have left abundant evidence of their life, such as settlements, fortified settlements, and burial grounds (Derevianko, 1981; Bolotin et al., 1998). As V.E. Medvedev observed, the Amur Jurchen people, “took a rightful place among the peoples of East Asia at the beginning of the second millennium” (1977: 158).

In the 10th century, a significant part of the Jurchen people became dependent on the Khitan people, and experienced the influence of the Liao statehood and

Fig. 3 . A grapheme from the “black” group.

Fig. 4 . Graphemes. Jurchen text. 2014.

culture. In 1115, the leader Aguda united the Jurchen tribes, ousted the Khitan people from the territory of Manchuria, and created the Jin State (1115–1234). The Amur region was located on the eastern periphery of this Jin State. According to the Chinese historical sources, in 1119 the Jurchen people created their first writing system that later became known as the Jurchen large script, and in 1138 they created a second system—the so-called Jurchen small script (Vorobiev, 1983: 151–152). Since most of the examples of Jurchen writing that have survived were written by the script of only one type, the question of identifying its type has long been and still remains debatable. Some scholars, for example A.M. Pevnov, call the script of these writings small (2004: 44); others, such as Aishingyoro Uruhichun and Yoshimoto Michimasa, considered it to be the large script (2017). Notably, according to their writing style, the graphemes of the Jurchen script recorded in the surviving writings are similar to the characters of the Khitan large script and the regular script style (kaishu) of the Chinese script (Kiyose Gisaburo, 1977: 22; Vorobiev, 1983: 151–152; Terentiev-Katansky, 1990: 77–80; Zaitsev, 2011: 141–148). We are following V.P. Zaitsev (2011: 141) calling this style the “Jurchen script” without indicating its type.

The involvement of the Jurchen ethnos and the Jin Empire in the medieval history and culture of the Amur region suggests that the text found on the rocks of the Arkhara site is Jurchen in origin. However, Jurchen texts are very rare.

Scholars have in their disposal a very limited number of texts written in Jurchen script. Thus, in 1842, N.Y. Bichurin stated, “The Gyin House (Jin 金 . – A.Z. ), which emerged in Ningut, was the first to invent letters for the Tungus language and, possessing North China and Mongolia for over a hundred years, used its own script in written relations. <…> With the fall of the Gyin House, all writings and translations written in the Tungus language and even the script itself completely disappeared, so not a single monument of the written language of the 12th century could be found among the Tungus tribes so far” (2002: 232–233).

Since the mid 19th century, the situation with the discovery and scholarly reconstruction of the examples of the Jurchen writing has significantly improved, but so far the number of monuments of Jurchen writing available to scholars is very small. The information on their number varies: this depends on which texts a particular scholar includes or excludes from consideration for various reasons. We have inscriptions both on stone and metal, and documents on paper. According to Pevnov, the body of the Jurchen epigraphy of the 12th– 15th centuries is represented by: 1) nine texts carved on stone, on steles or simply on rock faces, including six texts found in China, two in North Korea, and one in Russia, 2) “concise inscriptions or individual characters drawn on raw or fired clay of vessels (prior to firing, the characters were apparently written by the potter; inscriptions on the finished vessels were probably made by their owners)”, 3) “written characters on some seals, inkstone, brands, stamps, various iron objects and, finally, on such a unique object as a silver paiza”, and 4) “characters, probably of the Jurchen script, on the edges of bronze mirrors” (2004: 44–45, 48, 49). Despite the fact that the information of Pevnov on the texts of the first type is based on the book of the Japanese scholar Kiyose Gisaburo Norikura, “Study of the Jurchen

Language and Writing: Reconstruction and Decoding” (1977) and is somewhat outdated, it still allows us to get an idea of the number of monumental inscriptions available to scholars.

In his work, Kiyose Gisaburo provided additional evidence about these texts and indicated their location: several were discovered in Northeast China in the Jilin and Shandong Provinces, and near the city of Kaifeng (Henan Province); one inscription on a rock face, and one on a stele have been preserved in Korea, and a stele with a pecked inscription was set on the Tyr cliff, in the Lower Amur River region. The last stone-written Jurchen text on the list of the Japanese scholar (Tsagan Obo) was found in the Xilingol Aimag in Inner Mongolia in 1945, but nothing more is known about this text (Kane, 1989: 69). According to Kiyose Gisaburo, the earliest text (stele in the memory of the victory of Aguda, the future first emperor, Jin, over the Khitans; the left bank of the Lalin River, Fuyu County in Jilin Province) was dated to the 28th day of the 7th lunar month of 1185; the latest text (stele in honor of the construction and restoration of the temple of Yǒngníng Sì; the Tyr cliff) was dated to the 22nd day of the 9th lunar month of 1413 (Kiyose Gisaburo, 1977: 23–25; Golovachev et al., 2011: 96, 132). One of the undated Jurchen texts mentioned by Kiyose Gisaburo was subsequently attributed to the period before 1185. It was cited on the Gyeongwon stele in honor of construction of a Buddhist temple, which was dated to 1138–1153 (Kane, 1989: 59–62). Notably, in addition to these and several other inscriptions (Ibid.: 69) discovered after the publication of Kiyose’s book, texts written in the Jurchen script with ink on stone are also known. Such is, for example, the inscription on the wall inside the White Pagoda (Chinese báitǎ 白塔 ) in Hohhot (Ibid.: 77).

Thus, the inscriptions on steles and rock surfaces are a part of the body of the Jurchen writing culture. However, all inscriptions on stone in the Jurchen script known by 2003 were discovered in locations far from the left bank of the middle Amur River and the Arkhara River.

For conducting linguistic research and decoding the text, in 2003–2014 we established contacts with Russian experts in the Jurchen language and writing, Jurchen and Manchu scholars, and Sinologists. However, final identification of our text as Jurchen and translating it at this research stage proved to be difficult. At the Third Scholarly Conference on the History of Northeast China in Dalian (October 31, 2014), we showed the inscription to Jin Shi, an expert in Jurchen and Manchu studies, who confirmed that the graphemes constituted the written signs of the Jurchen large script. For continuing the study of the text, Jin Shi suggested giving the text to a major specialist on the Jurchen language and writing Prof. Aishingyoro Uruhichun (Aisin Gioro Ulhicun in Manchu) from the Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto.

Aishingyoro Uruhichun was given the photographs of rock representations and their tracings made in 2003, and our publications on the inscription, specially translated into Chinese by Wang Jianlin.

To finally establish the authenticity of the inscription, accuracy and completeness of its copying, the Laboratory of Archaeology and Anthropology of the AmSU in 2015 conducted an international expedition, which included A.P. Zabiyako (head), Wang Jianlin, and A.O. Belyakov (laboratory employees) on the Russian side, and Aishingyoro Uruhichun and Kai He on the Japanese side. Visual inspection and photographing of the inscription have made it possible to confirm the authenticity of the graphemes as an example of the Jurchen writing, completeness of their recording, and adequacy of translation.

After completing the field part of the study, the Russian participants made plans with their Japanese colleagues for further processing of joint field materials and publishing the entire set of scholarly results in the form of a collective monograph in the Russian and Japanese languages. For preparing the monograph, the Russian side gave Aishingyoro Uruhichun the publications (translated into Chinese by Wang Jianlin) devoted to the Arkhara rock representations, revealing the history of the Amur Jurchen people, as well as information about the climatic and landscape conditions of the region, and other materials. All of this information was included in the monograph by Aishingyoro Uruhichun and Yoshimoto Michimasa (2017), published without discussion with the Russian side. This book is certainly an important contribution to the study of the Jurchen language and writing. Unfortunately, it contains significant inaccuracies in the presentation of the history of research on the Arkhara rock inscription; there is no comprehensive historiography on the topic of researching the text; and some Russian materials that were not intended for publication were published.

In 2016–2018, employees of the Laboratory of Archaeology and Anthropology of the AmSU continued to study this unique monument together with Russian and foreign experts. Historical and philological research of new and previously identified epigraphic evidence (texts written in the Jurchen script) in the framework of these studies, has been carried out by V.P. Zaitsev—an employee of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Results and discussion

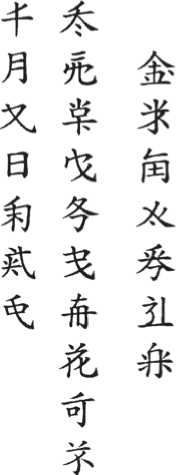

The most important result of studying the petroglyphs of the Arkhara site was the discovery in 2003 and final identification in 2014 of the text from the “black” group as an example of the Jurchen script, and its subsequent deciphering, translation, and interpretation. Twenty four characters of the Jurchen script have been identified and reconstructed (decrypted from the cursive form and correlated with the evidence from other texts written in the Jurchen script) in the cursive text consisting of three vertical lines, which should be read from right to left: seven, ten, and seven characters in the first, second, and third line of the text, respectively (Aishingyoro Uruhichun, Yoshimoto Michimasa, 2017: 30) (Fig. 5).

In the phonetic reconstruction of the Jurchen written characters by Aishingyoro Uruhichun, the Arkhara text looks as follows: (1) pulan imula ʃunʤa ania (2) tarɣando i oson muə pərgilə gai-man (3) ʤua bia oniohon inəŋgi ʃin-tərin (Ibid.: 31–32). This text was translated and interpreted in the following manner (the interpretations and comments of the researcher on the translation are given in square brackets; Russian edition and translation were made by Zaitsev) (Ibid.: 32–51):

-

(1) the fifth year [of the reign under the Tianhui regnal name of the Jin Emperor Taizong = 金太宗 天 會 , which is under the cyclic signs], ding-wei [Chinese 丁未 ; Jurchen pulan imula , literally, ‘red goat’];

-

(2) reached the lower [reaches] of a small river [Jurchen oson muə , literally, ‘small water’; points to the Arkhara River, the left tributary of the Amur River] in Targhando [Jurchen tarɣando ; in Chinese transcription, Taliando 塔里安 朶 ; in Japanese transcription Targhando タ ル ア ン ド ; in the Jin period, the name of mouke (Chinese 謀 克 )—a subordinate district, militarized or territorial community in the place where the rock was located];

Fig. 5 . Reconstruction of the text by Aishingyoro Uruhichun.

-

(3) tenth moon, nineteenth day. Shin Terin [Jurchen ʃin-tərin ; in Chinese transcription, Shēntēlín 忒 鄰 鄰 ; in Japanese transcription Sintokurin 申 忒 鄰 ].

In the literary translation: “[In] the fifth year [of the reign under the Tianhui regnal name of the Jin Emperor Taizong, which is under the cyclic signs], ding-wei reached the lower reaches of a small river [Arkhara] in [ mouke ] Targhando. [In] the nineteenth day of the tenth lunar month, [recorded by] Shin Terin”.

Some aspects of reconstructing such hardly legible characters as well as translation and dating by Aishingyoro Uruhichun were critically analyzed by the British scholar E. West, who emphasized the need to clarify the features of individual graphemes as well as their phonetic reconstruction and meaning (2018). We should mention that the work of the Japanese scholars, besides our preliminary tracings of the inscriptions of 2003 (for some reason mistakenly dated July, 2014), did not contain other tracings (Aishingyoro Uruhichun, Yoshimoto Michimasa, 2017: 30). Thus, other researchers are not able to establish on the basis of which tracings of the Arkhara text (certainly not always surely distinguishable in the photographs) the reconstruction was carried out, and to double-check the result. From our point of view, unfortunately, the monograph lacks an important intermediate link between the photograph of the text in situ and its published reconstruction: the author’s tracing of the text, which would form the basis of the reconstruction. We should agree that the linguistic remarks and original interpretations by the West are largely true. However, now we are following the published version by the Japanese linguist.

The text indicates when the inscription was made— on the 19th day of the 10th lunar month of the 5th year of reign under the Tianhui regnal name of the Jin Emperor Taizong, which corresponds to November 24, 1127 according to the Julian calendar, and December 1, 1127 according to the Gregorian calendar (Liangqian…, 1956: 226, 418). If the deciphering of Aishingyoro Uruhichun is correct, then, according to its date, the text on the rock of Arkhara is the earliest of all texts in the Jurchen script known to scholars. As it has been noted, before the discovery of the Arkhara text, the text on the Kyongwon stele (Chinese, Qingyuanjun Nuzhen guoshu bei 慶源郡女真國書碑 ), dated to 1138–1153, was considered to be the earliest (Kane, 1989: 59–62). The Arkhara text is separated from the Kyongwon text by 11–26 years. The time when the Jurchen script was created in 1119 and the inscription on the rock at the Arkhara are only about eight years apart. This makes it possible to consider the Arkhara inscription a unique monument of writing.

The Arkhara text is one of the earliest written sources discovered on the left bank of the Amur River and in the Russian Far East. On the lower Amur River in the early (not later than the early 12th century) Jurchen burial grounds, Medvedev has found fragments of vessels and bronze mirrors with Chinese characters and unidentified characters, and an inkstone (1986: 9–10, 15, 65). In Primorye, pottery and a silver paiza with Jurchen graphemes have been discovered (Pevnov, 2004). Thus, before the discovery of the Arkhara inscription, scholars had only archaeological evidence, individual written characters, and information from the Chinese chronicles on the history of that vast region prior to the early 12th century. Now scholars have a dated written text of local origin at their disposal.

The text indicates that a man named Shin Terin visited the Arkhara River in the territory of mouke Targhando in the autumn of 1127. Judging by the form of the characters painted on the rock, he was skilled in using a brush and writing in the new script. Obviously, Shin Terin was well-educated, and was a Jin official who was carrying out some kind of assignment on the left bank of the middle Amur River. “The History of Jin” (Jin Shi 金 史 )—the Chinese dynasty chronicle of the Jurchen state—makes no mention of the name “Shin Terin” and mouke Targhando, nor of the mission to the Arkhara. Certainly, not all events were reflected in official historiography, especially in the subsequent official histories (Zheng Shi 正史 ) compiled after the fall of the dynasties. Shin Terin’s activities could have been related to the local centers of the Jurchen administration. The largest Jurchen fortress closest to the mouth of the Arkhara was the fortress on Mount Shapka. The studies by the Russian archaeologists have established that the Shapka settlement was one of the Jurchen trading, artisanal, administrative, and military centers that controlled the nearby territory (Derevianko, 1988; Nesterov et al., 2011).

The use by Shin Terin of the Jurchen script, which had been created only a few years before his visit to Arkhara, can be considered an indicator that the author of the text was close to the capital’s circles, where he managed to learn a new type of script, or alternatively, of fast and wide spread of the Jurchen script up to the eastern borders of the Jin Empire—the left bank of the Amur River.

The Arkhara text is an important source for reconstructing the historical toponymy of the region: it indicates that in the 12th century, in the lower reaches of the Arkhara River, there was a militarized or territorial community (mouke), called Targhando by the Jurchen people (for the mengan system and mouke among the Jurchen people, see (Vorobiev, 1975: 55–57, 75–76, 130–134, 150, etc.)). This evidence supplements the information on the borders of the territory of settlement and migration of the Jurchen people in the period of the Jin Empire as well as the spread of their culture to the adjacent regions of East and Northeast Asia. The discovery of the inscription and its translation expand the linguistic capacities for studying the Jurchen people, in particular, the lexical composition of their language and aspects of their writing.

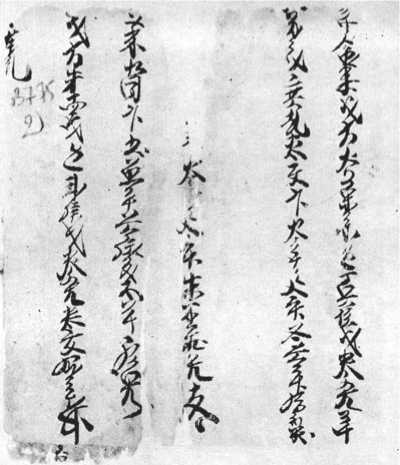

It is important that the published Jurchen text from the “black” group is not the only one from the site. In 2003, graphemes were discovered in the “red” group of rock representations. Since 2003, their identification, recording, and interpretation have been underway. In this article, for the first time we introduce one of the graphemes from the “red” group. It does not differ from the graphemes of the “black” group in terms of size, style, and execution technique. In our opinion, it is a grapheme of the Jurchen script (Fig. 6).

Since the entire text of the “red” group has not yet been reconstructed, an accurate interpretation of this individual sign is difficult. Nevertheless, as a justification for our conclusion, we can point to the similarity between the graphic form of this character and the fourth character in the second line of the Arkhara inscription (see Fig. 5), which according to the interpretation of Aishingyoro Uruhichun is an indicator of the Genitive (its cursive form is decrypted as the Jurchen grapheme i ^). Therefore, it is likely that the character being published is a grapheme of the Jurchen script with the same frequency (see (Kiyose Gisaburo, 1977: 63, No. 25; Pevnov, 2004: 154, V-52)). It also coincides with a grapheme in the cursive Jurchen text from the collection of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg (Kara, Kychanov, Starikov, 1972: 398, cols. 3, 6, 7; 399, lines 1, 2, 5) (Fig. 7, 8).

Prospects for further research should involve clearing all surfaces with representations from natural (vegetation) and anthropogenic (visitors’ inscriptions) layers, recording all signs, and making complete identification of the graphemes from the “black” and “red” groups, their translation, and interpretation.

Conclusions

The Arkhara rock art site contains over 350 figurative and non-figurative representations, and it is one of the richest petroglyphic monuments of Northeastern and Eastern Eurasia. The inscription discovered on the cliff above the Arkhara River in 2003 and translated in 2014 is the earliest known Jurchen text, making the Arkhara site a unique historical object. The Arkhara inscription, dated to 1127, is a crucial contribution to the small body of texts that have survived since the creation of the Jurchen script in 1119. The content of the inscription expands our knowledge about the historical toponymy of the region, territorial, political, and social organization of the Jurchen people living in the Amur region, and boundaries of the written culture of the Jin Empire. Identification of new Jurchen graphemes in the group of

Fig. 6 . A grapheme from the “red” group of rock representations at the Arkhara site. 2014.

Fig. 7 . Handwritten Jurchen text on paper from the collection of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg (Tangut Fund, inv. No. 3775-1).

Fig. 8 . Handwritten Jurchen text on paper from the collection of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg (Tangut Fund, inv. No. 3775-2).

the “red” signs will hopefully give new information on the Jurchen people, their history and culture.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Russian and international scholars, both predecessors and contemporaries, who participated in accumulation of knowledge concerning the composition and semantics of rock representations from the Arkhara River, as well as voluntary assistants; without their participation, field studies would not have been possible: A.A. Burykin, V.P. Zaitsev, R.A. Kobyzov, V.E. Larichev, A.I. Mazin, A.P. Okladnikov, T.A. Pan, T.A. Parilova, M.P. Parilov A.M. Pevnov, N.V. Chirkov, S.V. Filonov, Aishingyoro Uruhichun, Wang Jianlin, Wang Yulang, Kai He, Jin Shi, and A. West.