Archaeological evidence of migration from the southern taiga of Western Siberia to the Urals in the early Middle Ages: the Vodennikovo-1 cemetery

Автор: Matveeva N.P., Tretyakov E.A., Zelenkov A.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146413

IDR: 145146413 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2021.49.4.091-099

Текст статьи Archaeological evidence of migration from the southern taiga of Western Siberia to the Urals in the early Middle Ages: the Vodennikovo-1 cemetery

In the late 6th–8th centuries AD, the historical and cultural situation in Western Siberia changed significantly. The main factor causing changes was the Turkic expansion into the valleys of the Tobol, Irtysh, and Ob Rivers (Troitskaya, Novikov, 1998: 85–86; Chindina, 1991: 129; Mogilnikov, 1987: 234; Klyashtorny, Savinov, 2005: 86–87). The extensive economy and military policy of the nomadic states forced a part of the local population to search for new habitation areas. One of the directions was to move beyond the Urals.

Scholars have repeatedly raised the question of the participation of Siberian migrants in the emergence of the Kushnarenkovo-Kara-Yakupovo culture (Matveeva G.I., 2007; Gening, 1972: 270–272; Ivanov V.A., 1999: 68– 71; Mazhitov, 1981: 27–28) of the southern Urals, while taking notice of the Potchevash and Bakalskaya cultures, and the sites of the “Molchanovo” type of Western Siberia. The main arguments for the migration hypothesis were some common features in types of burials, as well as pottery shape and ornamentation technique. However, the sporadic nature of such similarity did not make it possible to establish the time of migration and mechanism

of interaction between the groups of the Early Medieval population in Western Siberia during the migration process.

The evidence from the Vodennikovo-1 cemetery reflects one of the stages in migration by the carriers of the Potchevash culture of the Ishim-Irtysh region to the Urals, and demonstrates the result of their interaction with the Bakalskaya people.

Sources

The Vodennikovo-1 cemetery is located in the Kurgan Region, on the bed-rock terrace of the right bank of the Iset River, at its confluence with the Miass River. The site was discovered by M.P. Vokhmentsev, and was studied by E.A. Tretyakov in 2019 and N.P. Matveeva in 2020. The cemetery consists of 54 burial mounds 0.3–0.9 m high and 5–10 m in diameter, arranged in dense chains at a distance of 3–10 m from each other. Two periods of its functioning have been recorded: the Early Iron Age and the Middle Ages. The medieval evidence will be discussed in this article. Eight burial mounds, containing from one to four burials, both individual and collective, including inlet burials (Tables 1, 2)* have been examined.

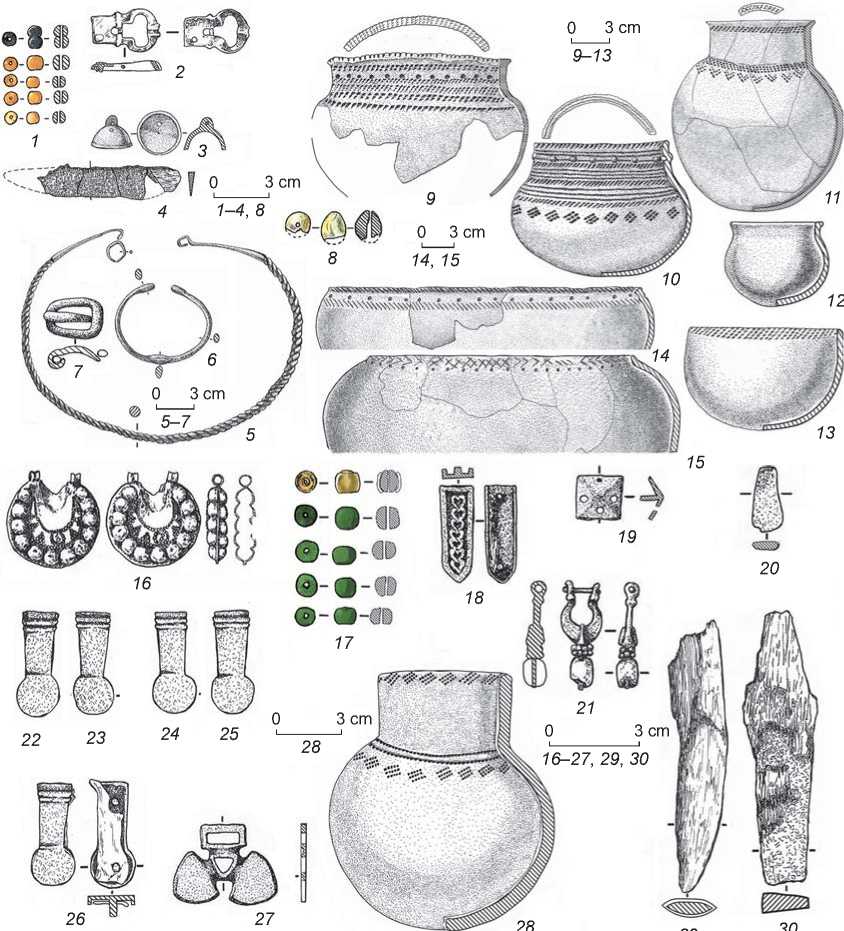

Burial 2 , an inlet child burial, contained no surviving remains; it was made in a rectangular wooden box set at the edge of the mound fringe. The box was 17 cm high; it was made of half logs 6–7 cm wide; the lid consisted of longitudinally laid boards 1.5–2.0 cm thick; the bottom was covered with wide sheets of birch bark. A bowl was placed in the southwestern corner of the box (Fig. 1, 13 ), and in its central part a thigh bone of large cattle was found. A small pot was located 0.3 m south of the burial (Fig. 1, 12 ). From the wall of the box, a sample for radiocarbon analysis was taken, which gave a chronological range of the 7th–8th centuries. The bowl, with talcum powder in the clay composition, was decorated with imprints of a comb stamp along the rim. The round-bottomed pot was undecorated; it had an everted rim and straight neck, and was very similar to the Bakalskaya pottery from burial 60 of the 8th–9th centuries from the Khripunovskoye burial ground (Kostomarova, 2007: Fig. 1, 2 ) and from the habitation layer of the 4th–8th centuries at the Kolovskoye fortified settlement (Matveeva N.P., 2016: Fig. 82, 2 ). Thus, burial 2 can be dated to the 7th–8th centuries.

Burial 3 was plundered; the remains have not survived. A vessel was found in the western part (Fig. 1, 10 ); tubular bone and joints of an animal were discovered in the eastern part of the grave pit. This low, round-bottomed pot, with straight edge slightly sloping

*The numbering of burials is sequential, according to the order of excavations over the entire burial ground.

inward and neck slanting inward, was decorated with slanting comb imprints and two cord lines along the side; a belt of “pearls” and alternating belts of slanting comb imprints and cord lines are located along the neck, with stamped rhombuses along the shoulder. The vessel finds its parallels in the evidence of the Karanayevo burial ground of the 9th–11th centuries in the southern Urals (Kazakov, 1992: Fig. 100, 1 ). A similar ornamental composition appears on the pottery from burial 28 at the Bolshiye Tigany cemetery of the late 8th to 9th centuries (Khalikova, Khalikov, 2018: Pl. XXII, 23 ), except that the grooves were carved in the latter case, and consisted of cord imprints in the former case.

Burial 4 did not contain any finds.

Burial 5 was completely plundered.

Burial 6 contained an adult molar* and four ribs of an animal in the filling of its western part. Bands of wood decay up to 0.65 m long were found along the walls. Long human leg bones survived from the buried person. Fragments of an iron knife (Fig. 1, 4 ) and bead (Fig. 1, 8 ) were discovered near the southern wall; a crushed vessel (Fig. 1, 9 ) and buckle were found in the middle. Knives with straight backs widely occur in the inventory of medieval burials in Western Siberia (Viktorova, 2008: 51–55; Matveeva N.P., 2016: 171). The ovoid, light brown, translucent glass bead (Fig. 1, 8 ) of type IIIA2, according to the classification of E.V. Goldina, finds parallels among the evidence from the Nevolino and Sukhoy Log cemeteries (Goldina E.V., 2010: 29–30). The vessel, a round-bottomed pot (Fig. 1, 9 ) with straight neck, was decorated in the Bakalskaya style with a comb along the rim, and a band of pits and horizontal rows of slanting short comb imprints along the neck. The iron, shieldless trapezoidal buckle (Fig. 1, 7 ), with a movable prong that did not protrude beyond the edge, finds parallels in the evidence from the Starokhalilovo burial ground of the 9th–10th centuries (burial 15, kurgan 6), the Karanaevo burial ground of the 9th–11th centuries (burial 4, kurgan 7) (Mazhitov, 1981: 102, Fig. 55, 16 ; p. 115, fig. 61, 3 ), and the Verkh-Sainskoye burial ground of the 6th–9th centuries (burials 19 and 61) (Goldina R.D., Perevozchikova, Goldina E.V., 2018: Pl. 146, 10 ; 179, 2 ) in the Cis-Urals. Buckles from the Nevolino cemetery of the 7th–9th centuries are somewhat larger in size (Goldina R.D., 2012: Pl. 76, 1 ; 86, 5 ; 156, 3 ). Based on the parallels, kurgan 20 can be dated to the 8th–9th centuries.

Burial 7 was dug up; the long bones of an adult human skeleton were found.

Burial 8 contained skeletal remains of a 25–35 year old female, with leg bones in situ . An iron knife, which crumbled when removed, lay near the right thighbone

Table 1. Features of the examined burial mounds

|

No. |

Size, m |

Height, m |

Numbers of burials |

Objects on the area under the mound |

|

6 |

10 × 9 |

0.4 |

2 |

Pot, 0.3 m south of burial 2 |

|

7 |

12 × 11 |

0.9 |

9, 10 |

Calcined spot, pot with slanting imprints of comb stamp, and animal bones near the western border of the mound |

|

8 |

7 × 4 |

0.25 |

3–5 |

– |

|

20 |

6 × 7 |

0.3 |

6 |

The jaw of a foal, and vessel decorated with horizontal rows of slanting short imprints of comb stamp under the western fringe |

|

21 |

6 × 7 |

0.3 |

18 |

Vessel with comb patterns, band of pits, and horizontal cord imprints; carcass of a small ruminant on the cover |

|

29 |

7 × 7 |

0.4 |

7, 8 |

Accumulation of fragments remaining from five ceramic vessels 0.5 m from burial 8 |

|

31 |

8 × 9 |

0.5 |

12 |

Two jugs with comb patterns, and animal bones under the northwestern fringe |

|

33 |

8 × 9 |

0.4 |

13, 15–17 |

Accumulations of broken pottery, animal bones, and intact vessels near burials 13, 16, 17; bowl outside the mound on the southeast |

Table 2. Description of burials

|

No. |

Shape |

Place in the burial mound |

Size, m |

Depth from the sterile soil, m |

Orientation |

|

2 |

Rectangular |

Inlet |

1.02 × 0.73 |

– |

NW-SE |

|

3 |

ʺ |

Peripheral |

2.00 × 0.85 |

0.35 |

W-E |

|

4 |

ʺ |

Central |

2.9 × 1.2 |

0.65 |

ʺ |

|

5 |

ʺ |

Peripheral |

1.86 × 0.72 |

0.25 |

ʺ |

|

6 |

ʺ |

Central |

2.5 × 0.84 |

0.70–0.66 |

ʺ |

|

7 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

2.46 × 0.93 |

0.6 |

NW-SE |

|

8 |

ʺ |

Peripheral |

2.5 × 0.8 |

0.23–0.24 |

ʺ |

|

9 |

ʺ |

Inlet |

2.0 × 0.6 |

– |

ʺ |

|

10 |

? |

ʺ |

2.15 × 0.65 |

0.25 |

W-E |

|

12 |

Trapezoid |

Central |

4.40 × 2.75 |

0.45 |

NW-SE |

|

13 |

Rectangular |

Peripheral |

1.90 × 0.95 |

0.3 |

ʺ |

|

15 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

1.9 × 1.1 |

0.2 |

NNW-SSE |

|

16 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

1.20 × 0.63 |

0.2 |

NW-SE |

|

17 |

Oval |

Central |

3.8 × 2.8 |

0.5 |

W-E |

|

18 |

Rectangular |

ʺ |

2.45 × 0.80 |

0.68 |

NW-SE |

of the buried woman. Pottery from the area under the mound consisted of small pots and cauldron-like vessels (Fig. 1, 14 , 15 ) typical of the Bakalskaya culture; their distinctive features were notches along the edge, a carved “herringbone” pattern, and a band of pits. Similar vessels have been found at the Ust-Tersyuk fortified settlement of the 4th–9th centuries (Rafikova, Matveeva, Berlina, 2008:

Fig. 17), Kolovskoye fortified settlement of the 4th–8th centuries (Matveeva, Berlina, Rafikova, 2008: Fig. 113, 3 ), Bolshoye Bakalskoye fortified settlement of the 3rd– 8th centuries (Botalov et al., 2008: Fig. 4, 10 , 13 ), and others. A small jug with a comb zigzag along the rim and cord lines along the neck (Fig. 2, 12 ) was found in the mound of kurgan 29. Its parallels appear in the evidence

9–13

3 cm

1–4 , 8

14 , 15

Р^г? *mw? ^

3 cm

5–7

3 cm

3 cm

16–27 , 29 , 30

®-Q-98 ®-о -sb

@-0-86

0-0-96

0 3 cm пйттиттггтг,: • \Mr*„Л/.- *v.**-.v,*z •■r.v'w'f^^TiAA

'^rff^r^f^r^t^rff^z--^^^z’ :

0 3 cm

21 0

Fig. 1 . Items from the burials.

1 , 8 , 17 – beads; 2 , 7 – buckles; 3 – half of a round, small bell; 4 , 29 , 30 – knives; 5 – torque; 6 – bracelet; 9–15 , 28 – vessels; 16 – kolt; 18 – belt tip; 19 , 22–26 – cover plates; 20 – chisel; 21 – earring; 27 – belt dispenser.

1 , 3 , 5 , 6 – burial 9; 2 – burial 10; 4 , 7–9 – burial 6; 10 – burial 3; 11 – kurgan 7; 12 , 13 – burial 2; 14 , 15 – kurgan 29; 16 , 17 – burial 18; 18–20 , 27 – burial 12; 21 – burial 16; 22–26 , 28 , 30 – burial 13; 29 – burial 17.

1 , 8 , 17 – glass; 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 , 18 , 19 , 21 – 27 – bronze; 4 , 7 , 20 , 29 , 30 – iron; 9–15 , 28 – clay; 16 – gold.

from the Manyak burial ground of the 7th–8th centuries in the southern Urals (Mazhitov, 1977: Pl. XXVIII, 1 ). Thus, kurgan 29 can be dated to the 7th–8th centuries.

Burial 9 was found at the level of the sterile soil. The remains of a female 35–45 years of age, buried in the extended supine position, with head to the northwest, were discovered in a block of solid wood about 0.25 m high, with a cover of poles and birch bark tightly placed in the longitudinal direction. A torque and beads were found under the lower jaw; a bracelet was on the bones of the right wrist, and half of a small, round bell lay next to it. The bracelet, made of a bronze rod, had bulges at the ends and in the center (see Fig. 1, 6). A similar adornment from the Nevolino necropolis dates back to the 7th century (Goldina R.D., 2012: Pl. 172, 16). Bracelets of this type are known from the evidence of the Pereyma (Chernetsov, 1957: Pl. XIII, 1), Likhacheva (Gening, Zdanovich, 1987: Fig. 3, 11), and Okunevo III (Mogilnikov, Konikov, 1983: Fig. 9, 10) cemeteries. The twisted bronze torque with conical ends (see Fig. 1, 5) was similar to the adornments

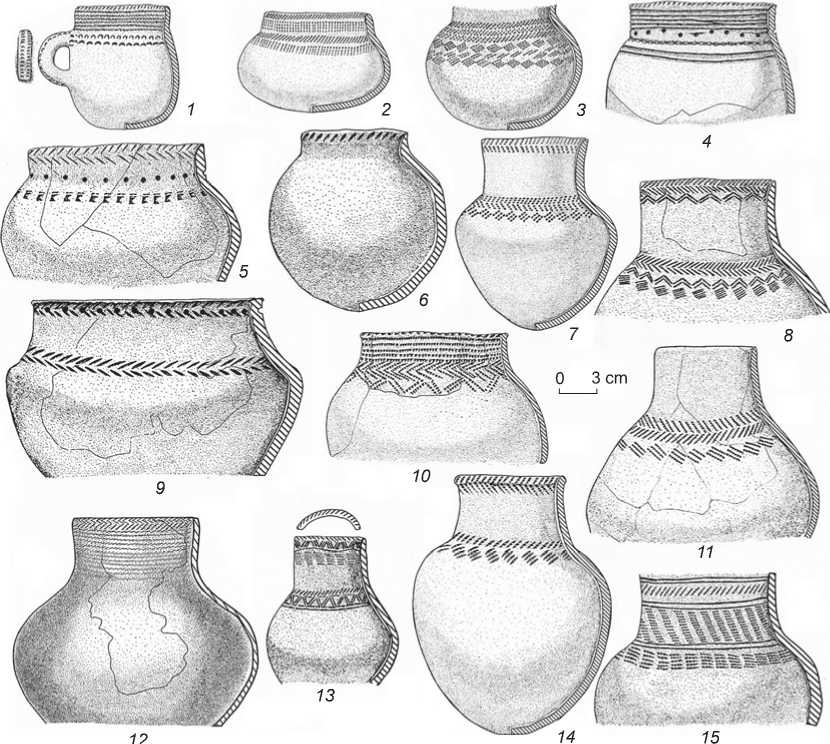

Fig . 2 . Pottery complex of the Vodennikovo-1 cemetery.

1–4 – burial 12; 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 13 , 15 – mound of kurgan 33; 7 , 14 – mound of kurgan 31; 10 – burial 17; 12 – mound of kurgan 29.

of this type in the inventory complexes of the 8th century at the Nevolino necropolis (Goldina R.D., 2012: Pl. 212, 13 ). The glass beads were barrel-shaped; one was double and opaque black; four were gilded (see Fig. 1, 1 ). They belong to types IА51, IВ21, and date to the late 7th– 8th centuries (Goldina E.V., 2010: Fig. 20, 21, p. 57). The cast, bronze half of a small bell with an eyelet for hanging (see Fig. 1, 3 ) finds parallels in the clothing complexes of the late 7th–8th centuries at the Nevolino (Goldina R.D., 2012: Pl. 172, 4–7 , 10 ), Manyak, and Lagerevo (Mazhitov, 1981: Fig. 6, 13 ; 7, 13 , 14 ; 11, 11 , 12 ) cemeteries, and in the inventory of the 8th century burial at the Polom I site (Ivanov A.G., 1997: Fig. 18, 15 ). Thus, burial 9 can be dated to the late 7th–8th centuries.

Burial 10 was plundered. The femur bones of an adult, whose sex could not be established, were preserved in situ . A bronze buckle with immovable rectangular shield, lyre-shaped frame, and pin for attaching to the belt (see Fig. 1, 2 ) were found near the right bone. Similar items are known from the Nevolino, Agafonovo, and Polom complexes of the 7th–8th centuries (Goldina R.D., 2012:

Pl. 206, 29 , pl. 223, 7 ; Ivanov A.G., 1997: Fig. 18, 15 ), which makes it possible to consider this burial to be contemporaneous with the previous one. Such buckles have been found at the Manyak (Mazhitov, 1981: Fig. 3, 1 ), Okunevo III (Mogilnikov, Konikov, 1983: fig. 2, 1 , 4, 4 , 9, 18 ), and Likhacheva (Gening, Zdanovich, 1987: Fig. 2, 16 ) cemeteries.

A round-bottomed pot from the area of kurgan 7 had a straight neck and everted rim; it was decorated with slanting comb imprints and double zigzag (see Fig. 1, 11 ). All these features are typical of the Bakalskaya pottery (Matveeva N.P., 2016: Fig. 81).

Burial 12 was a collective burial of four people placed in a row across the grave. Individual 1 (senilis age, gender undetermined) occupied an extreme position at the narrow end of the pit. This person was laid on his back with head to the northeast. A mug with a handle (see Fig. 2, 1) and low pot (see Fig. 2, 2) were near the skull, which showed traces of artificial deformation. Remains of leather and a belt tip were found in the belt area. A fractured skull and femur have survived from individual 2 (adultus age, gender undetermined) at the wide end of the pit. Two vessels (one undecorated and one with a comb-like ornamentation), and leg bones of an ungulate animal lay nearby. Fragments of the skull of individual 3 (maturus age, gender unknown) were also found there. A part of the postcranial skeleton and skull bones of individual 4 (maturus male) lay in the middle of the grave. The skull was artificially deformed; in addition, it showed traces of traumatic injury (a cut?). A pot with a comb-like pattern (see Fig. 2, 3), iron item similar to a chisel blade (see Fig. 1, 20), animal bones, and onlay plaque with holes were also in that area. A pot with carved decoration was placed at the head of individual 4 (see Fig. 2, 4), and a belt dispenser was found nearby.

Two jugs with ovoid bodies and concave necks, decorated with horizontal comb “herringbone” and rhombuses (see Fig. 2, 7 , 14 ), were discovered in the mound of kurgan 31. They show parallels to the complex of the Pereyma burial ground of the 7th–8th centuries (Matveeva N.P., 2016: Fig. 77, 2 , 5 ). Pottery from burial 12 was heterogeneous, including: the round-bottomed pot with three bands of slanting comb imprints and three rows of rhombuses (Fig. 2, 3 ); the cylindrical cup with handle decorated with notches along the rim; six rows of short, slanting comb (pseudo-cord) imprints and a band of “horseshoes” and angle-like signs below (see Fig. 2, 1 ); the low, round-bottomed pot with comb imprints (see Fig. 2, 2 ); the vessel with rounded bottom and straight neck, decorated with notches along the rim, multi-row horizontal carved grooves, a band of pits and grid (see Fig. 2, 4 ), as well as an undecorated pot. It can be stated that these vessels were syncretic and combined the Bakalskaya patterns and Potchevash manufacturing technique.

The bronze belt dispenser with rectangular loop and two heart-shaped lobes (see Fig. 1, 27 ) finds parallels in the evidence from the Kushnarenkovo burial ground of

the 6th–7th centuries in the southern Urals (Gavritukhin, 1996: Fig. 4, 79 ). A bronze tip of elongated trapezoidal shape with pins for fastening to the belt (see Fig. 1, 18 ), decorated with a chain of heart-shaped links and band along the edge, was similar to the items of the same type of the 7th–8th centuries from Nevolino (Goldina R.D., 2012: Pl. 184, 11–14 ). The dating of bronze square tetrahedral belt cover plates, with holes in the middle of each facet and pin for fastening to the belt, fits the same chronological framework (see Fig. 1, 19 ). They are known from the evidence found at the Manyak cemetery of the 8th century (Mazhitov, 1981: Fig. 7, 32 ) and Ust-Suerskoye-1 cemetery of the 7th–8th centuries (Maslyuzhenko, Shilov, Khavrin, 2011: Fig. 6, 18 ). Thus, kurgan 31 can be dated to the 7th–8th centuries.

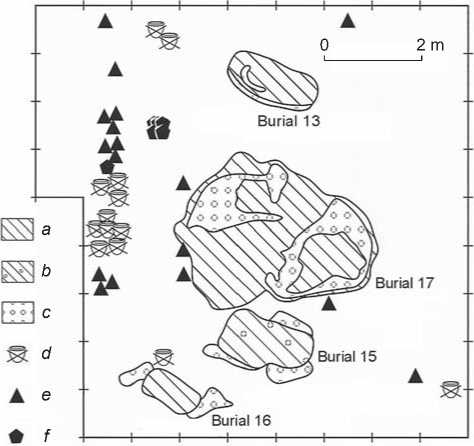

All four burials of kurgan 33 were completed before its mound was made (Fig. 3). Commemorative meals were performed at the site of the graves several times. Two Bakalskaya vessels associated with burial 13 were located 1.5 m west of it (see Fig. 2, 9 ). One small pot stood at the head of burial 16 on the outside (see Fig. 2, 6 ). Ten vessels are associated with burial 17 and are located 1.5 m west of it. One group contained three broken jugs. Three small Bakalskaya pots (see Fig. 2, 5 ) and a cup, along with three Potchevash jugs (see Fig. 2, 8 , 13 , 15 ), constituted another accumulation of pottery. A crushed bowl was found under the southeastern fringe of the burial mound; fragments of necks and walls of vessels with comb patterns, as well as animal bones, were discovered under the northwestern fringe, 15–20 cm deeper than the above-mentioned broken pottery. After the commemoration meal, they were probably placed into pits that are now not visible. The fact that some of the vessels appear in broken form, and some intact, speaks for the different time of commemorative activities near the graves.

Eight vessels from the area under the mound included round-bottomed pots and jars with pits under the rim, comb imprints or notches in the form of a grid and “herringbone” pattern. The decoration was sparse; the clay was mixed with chamotte. This pottery has broad parallels in both burial and habitation complexes of the Bakalskaya culture of the 4th–8th centuries in the Tobol-Ishim region (Rafikova, Matveeva, Berlina, 2008: Fig. 14–17; Matveeva, Berlina, Rafikova, 2008: Fig. 113–118; Botalov et al., 2008: Fig. 4–7). Six thinwalled jugs with narrow, high, straight necks and spherical bodies, decoration of rhombuses, “herringbone”, and double zigzag, made by tracing and thin comb (see Fig. 2, 8 , 11 ), are similar to the Pereyma pottery of the 7th–8th centuries. One jug (see Fig. 2, 15 ), according to

Fig . 3 . Plan of the structures under the mound of kurgan 33. a – dark gray filling; b – dark gray mixed filling; c – discharged loam; d – collapsed vessel; e – faunal remains; f – pottery fragments.

its ornamental pattern, belongs to the typical Potchevash tradition (Ilyushina, 2009: Fig. 3, 4 , 4, 8 ).

Burial 13 was a cenotaph, since the bones of the skeleton were missing, while the things were found in their usual places. Five belt cover plates were discovered in the middle of the pit; a short iron knife with traces of wood on the tang (see Fig. 1, 30 ) was nearby. A small jug with a high, straight neck and rounded body (see Fig. 1, 28 ), bands of horizontal comb imprints and rhombuses, similar to a Pereyma vessel (Matveeva N.P., 2016: Fig. 77, 5 ), stood in the southeastern end of the burial. Trapezoidal bronze belt cover plates with rounded ends and two pins for fastening them to the belt (see Fig. 1, 22 – 26 ) are similar to those of the Ust-Suerskoye items (Maslyuzhenko, Shilov, Khavrin, 2011: Fig. 6, 17 , 19 , 20 ), which makes it possible to date this burial to the 7th–8th centuries.

Burial 15 was plundered. Only fragments of the long bones of an individual at the age of adultus-senilis (the gender is unknown) have survived.

Burial 16 contained the remains of a 3- to 4-year-old child buried in the extended supine position with head to the northwest. A bronze gilded lyre-shaped earring with granulation and pendant-bead (see Fig. 1, 21 ) was discovered near the right temporal bone. The earring was dated to the 7th–8th centuries on the basis of parallels to the evidence from the Kudyrge cemetery in the Eastern Altai (Kenk, 1982: Abb. 14, 22 ).

Burial 17 was plundered; the bottom of the pit was dug up; things and bones of the skeleton were moved. They belonged to an individual 35–45 years of age (the sex is undetermined). Only an iron knife (see Fig. 1, 29 ) and pottery fragments (see Fig. 2, 10 ) have survived. Judging by the combination of pottery with the Potchevash fine-combed decoration and Bakalskaya pottery (a pot with cornice and horizontal bands of combs, and a bowl with pits under the rim and line of notches), this burial was contemporaneous with the three burials described above. Thus, kurgan 33 can be dated to the 7th–8th centuries.

Burial 18 contained leg bones of an adultus-senilis male. A temple adornment and five glass beads lying next to it were found at the head end of the grave. A two-piece gold kolt with two loops for attaching the unpreserved bow was decorated with “pearls” along the edge and pyramids of granulation in the center (see Fig. 1, 16 ). Close parallels appear in the complex of the 7th century at the Kudyrge cemetery in the Eastern Altai (Gavrilova, 1965: Pl. IX, 3 , 4 ). Similar adornments are known from the evidence of the sites of the 7th century in the Caucasus and the Carpathian Basin (Balogh, 2016). The dating of four green and brown opaque barrel-shaped beads (see Fig. 1, 17 ) belonging to type IA47 (Goldina E.V., 2010: Fig. 31) to the 7th–8th centuries agrees with this. Thus, kurgan 21 can be dated to the 7th–8th centuries.

Discussion

The inventory described above makes it possible to attribute the complex of Early Medieval burials at the Vodennikovo-1 cemetery from the second half of the 7th to the 8th century. The radiocarbon date of burial 2, obtained from the wood of the coffin by I.Y. Ovchinnikov at the Institute of Geology and Mineralogy of the SB RAS, indicates the intervals of 660–769 (68.3 % probability) and 641–880 (94.5 % probability). Thus, the Vodennikovo-1 cemetery fills the gap in the material evidence from the eastern slope of the Urals, which existed for the second half of the 7th–8th centuries.

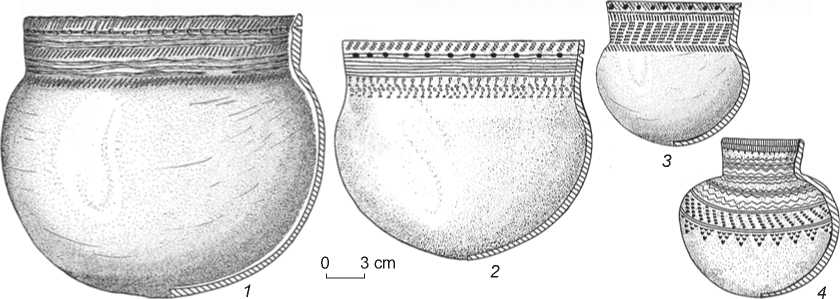

The results of studying fifteen burials demonstrate innovations in the funeral rite of the Bakalskaya culture. We consider the following features to be traditional for the forest-steppe population of Western Siberia: inhumations under low kurgans in narrow shallow pits oriented along the NW-SE line, collective burials, vessels in graves, as well as remains of the funeral feast in the mound in the form of animal bones and utensils (Matveeva N.P., 2016: 210). New features are burials in blocks of solid wood, western orientation of some of the deceased, inlet burials, joint occurrence of the Bakalskaya and Potchevash pottery in the same commemorative complexes (as for example kurgan 33), appearance of syncretic forms of pottery, as well as the stamped and grooved design (see Fig. 2). Parallels to some features of items from Vodennikovo-1 can be found in the above-mentioned contemporaneous necropolises of the Trans-Urals. For example, multicultural pottery was placed near the graves in Pereyma; western orientation and blocks of solid wood have been observed at Khripunovskoye and Ust-Suerskoye-1. However, the above innovations were traditional features of the burials of the Potchevash culture, known from the cemeteries of Likhacheva, Okunevo III, and Vikulovskoye, where parallels to the vessels with grooved and fine-combed ornamentation have also been found (Fig. 4). Interestingly, recent mixing of the multicultural population on the Iset River is reflected in placement of vessels of the same type in groups at the graves.

Previously, the movements of the southern taiga population groups from the Irtysh region in the 6th– 8th centuries to the Baraba forest-steppe (Molodin, Solovyev, 2004: 5–6) and to the steppe of North Kazakhstan along the Irtysh River (Arslanova, 1983: Fig. 1; Smagulov, 2006: 91) was mentioned in the literature. Evidence from Vodennikovo-1 suggests another migration route of the carriers of the Potchevash culture, namely, to the Urals, along the northern border of the forest-steppe. As a result of interaction with the Bakalskaya groups, the syncretic “Kushnarenkovo” pottery of jug-like forms

Fig . 4 . Pottery from the Potchevash burial grounds.

1 – Okunevo III; 2 – Vikulovskoye; 3 – Likhacheva; 4 – Bobrovka.

with carved, grooved, and fine-combed ornamentation (Zelenkov, 2019), whose origin is associated with imitation of prestigious pottery from Central Asia (Matveeva N.P., 2019: 51–52), emerged in that region. The components of these cultural traditions with the participation of the Turkic-speaking nomads determined the appearance of the Kara-Yakupovo complexes, which does not contradict the ideas about the cultural genesis of the population living in the southern Urals in the Early Middle Ages (Ivanov V.A., 1999: 66).

Conclusions

The Early Medieval evidence from the Vodennikovo-1 cemetery demonstrates innovations in the funeral rite of the Bakalskaya culture and indicates a cultural wave from the southern taiga of the Irtysh region in the late 7th–8th centuries. Migration of the groups of the Potchevash population to the west and east from their original area is reflected in syncretism of cultural entities throughout the entire forest-steppe of Western Siberia, northern Kazakhstan, and the southern Urals. It can be stated that finally it has been possible to obtain more reliable evidence showing the influence of the Potchevash people on cultural genesis in the Urals and Trans-Urals, and their contacts with the nomads of Kazakhstan. This evidence complements and develops the proofs provided by V.F. Gening, G.I. Matveeva, F.K. Arslanova, N.A. Mazhitov, and V.A. Mogilnikov. It is encouraging to find traces of interaction between the Potchevash and Bakalskaya populations as very likely speakers of the Selkup and Ugric languages, which influenced the vocabulary of the Magyars, formed in the zone of their settlement. As is known, the Magyar vocabulary includes relatively many words of the Samoyed linguistic group, which could have been borrowed only in the Trans-Urals (Khelimsky, 1982: 123–125). The reason for the latitudinal migration in the west of Western Siberia was probably the advance of the

Kimaks and Kipchaks in the 8th century. Information about this has appeared in several sources. Further development of this hypothesis requires additional arguments, including those based on anthropological and genetic data.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research and the Foundation “For Russian Language and Culture in Hungary”, Projects No. 19-59-23006 and 20-49-720001.