Are the youth Olympic Games a modernized embodiment of Coubertin's olympism?

Автор: Proger J., Scharenberg S.

Журнал: Физическая культура, спорт - наука и практика @fizicheskaya-kultura-sport

Рубрика: Из портфеля редакции

Статья в выпуске: 2, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Relevance. Pierre de Coubertin was the founder of the modern Olympic Games. His "Olympism" is a term that is difficult to define. That is why we use a model based on the multi-perspective approach created by German sports pedagogy to find out that Sinnperspektiven (the perspective of the senses) will create an educational surplus. Goal. Based on this definition of Olympism, we carefully consider the intent and implementation of the Youth Olympic Games (UOI) held since 2010. We do not analyze the results of the sports activities of talented young athletes, but focus on the preparation of athletes for the UOI, and their opportunities to become ambassadors of the "Cou-bertin" Olympism. Research methods. The multi-perspective approach refers to the principle of describing a phenomenon (Sinnperspektiven) by considering the various points of view through which this (phenomenon) can influence the feelings and contribute to the development of its students. Results. The study examines four main historical roots, as well as five specific perspectives of feelings, systematized through their connections. Conclusions. In conclusion, the use of the UOI to promote Olympic education, as was one of the IOC's goals, is a step in the right direction. However, the educational efforts of the UOI could be more effective if the Youth Games were not focused primarily on promising talents of the sports world, but rather took into account the interests and ambitions of teenagers who seek to instill the Olympic spirit and values in their communities (countries, states).

Youth olympic games (uoi), olympism, coubertin, multi-perspective approach

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/142226872

IDR: 142226872 | УДК: 796.032.2

Текст научной статьи Are the youth Olympic Games a modernized embodiment of Coubertin's olympism?

The year 2010 is a milestone in the change of modern Olympic movement. The launch of the Youth Olympic Games (YOG) marks the genesis of a new Olympic Games format after more than 80 years of consistency. Therefore the intentions are communicated properly by the IOC: The YOG are not only to supposed to be an international sporting competition for the up-and-coming talents of the sporting world but shall also contribute to the education of athletes making them become ambassadors of Olympism (Slater 2009).

Scientific experts call this out to be a return to the foundations of the Olympic Movement. The spectacular-ity and commercialisation of the established grand Olympic Games (in comparison to the rather small-scaled YOG) overshadow the fact that the modern Olympic Movement initially had the aim prioritized to foster the pedagogical concept of ‘education by sports’. Frenchman Pierre de Coubertin who is acknowledged to be the founding father of the modern Olympic Games was not only a sports visionary but also an educational reformer who in his lifetime tried to direct the Olympic Movement and form its ideology Olympism according to his educational convictions.

However are the YOG really a resurrection of Coubertin´s educational intentions in form of a modernized implementation? Or does the IOC in reality pursue different interest with this new franchise (e.g. economical or professional sporting interests)?

Coubertins Olympism

In a timespan of over 40 years Coubertin wrote numerous articles on the topic of Olympism and the perception that he described is versatile and complex – in some respects also inconsistent and even contradictory. This primarily can be traced back to him not regarding Olympism as a concept but rather as a self-explanatory philosophy of life (Müller 2000 p. 44). As a result Coubertin never bothered arranging his thoughts in a conclusive systematic conception and – quite contrary to that – used the term in a versatile manner which has caused the Olympism to be instrumentalized in different ways up to this day. From a general point of view Olympism as it has been presented by Coubertin is a transcultural ideology that idealizes (olympic) sports by binding it to service individual societal and global progression (vgl. Loland 2015).

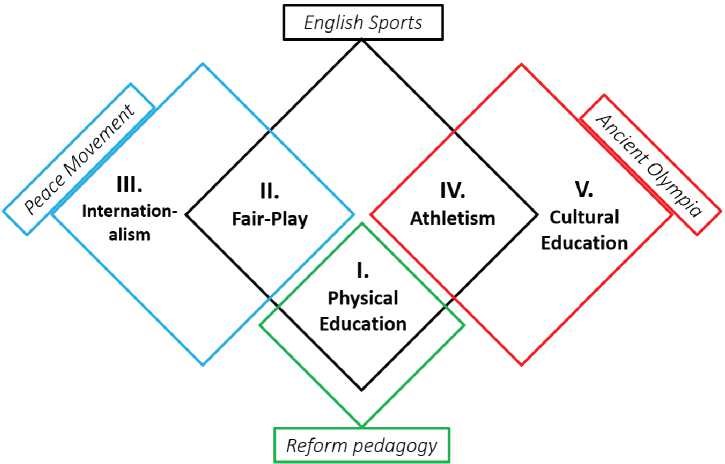

As written down in the Olympic Charter the IOC relies on Coubertin´s original thought by describing Olympism as a philosophy of life which bases on universal fundamental ethnical principles.Just as its thought leader the IOC also misses out on further clarifying the definition of Olympism – for example by not specifying the term ‘fundamental ethnical principles’ which Olympism is supposed to be based on (Teetzel 2015 p. 284). The academic literature provides significantly more detailed descriptions of Olympism but these approaches vary in accordance with scientific discipline prioritization and the structuring of contents (see Segrave Loland in Olympic Studies Vol. 1 (2015) and Teetzel in Olympic Studies Vol. 3 (2015)). The following model has been conceptualized for this thesis and offers a structuring of Olympism based on the multiperspective approach which has been developed in German Sports Pedagogy.

Method

The multi-perspective approach conceptualizes the principle of deducing a topic by considering different perspectives in which this topic may influence and contribute to the development of its receivers. The concept of Kurz (2004) being one of the most established in Ger- man Sports Pedagogy focuses on sports itself: sports can be perceived as meaningful in different ways (having fun staying healthy being social and other meanings) – Kurz therefore uses the German term ‘Sinnperspektiven’ (perspectives of meaning or literally: perspectives of senses). Whilst participating in sporting activities different perspectives of senses can define the participants motivation eventually changing and/or occurring simultaneously within one session and thereby also influencing the perception of the sporting situation (e.g. changing from ‘fun-oriented’ to ‘competition-led’ sports). The number of possible perspectives of senses as well as their phrasings interpretations and compositions are not predetermined – the multi-perspectivity of a topic (in case of Kurz sports here it is Olympism) can be received differently and does not claim to be comprehensive (Kurz 2004 p. 67 ).

This approach is suitable for understanding Coubertin´s Olympism for the following reason: In the Frenchman´s mind the Olympic idea was not exclusively but predominately an educational idea and he was in many ways convinced of the ‘character-forming’ effects of the Olympic Games he envisioned. As a result not every facet of Olympism covers educational goals (e.g. the independency of the IOCas an international organization) but still in Coubertin´s writings as well as in the interpretation of them there are periodic comprehensive pedagogy motives which are suitable to count as perspective of senses of Olympism. According to Loland (2015) these can be brought back to their historical roots – this enables us to understand the perspective of senses in contemporary context and to separate them clearly. The figure underneath displays the four main historical roots as well as the five determined perspectives of senses being arranged systematically due to their links.

From Coubertins point of view the concepts of peace movement English sports and reform pedagogy were modern trends which spread all over Europe during his life-time. The epos of ancient Olympia was not modern but still contemporary as the excavation of ancient Greek

|

Category |

Coubertin |

Yog |

|

I |

History is the silver bullet of education. The modern Olympic Games are supposed to bring the ancient festival back to life. |

Education is future oriented as athletes are confronted with current topics and get prepared for their future professional career. |

|

I |

With every edition of the Olympic Games new sporting venues are supposed to be established – Copying the Greek gymnasium and thereby fostering the concept of sporting education. |

Instead of constructing new venues the given sporting infrastructure is supposed to be modernized to foster sustainable thinking. |

|

IV |

Olympic athletes are men exclusively. |

There are competitions for men as well as women and even mixed-gender-competitions in which men and women compete side by side in pairings. |

|

V |

Besides the sporting competitions there are also competitions in architecture art music and literature as the cultural component of the Olympic Games is also supposed to be of importance. |

Competitions are held only in sports whilst art music and literature can be found only in certain workshops and programs of the CEP. |

sites of civilisation caused a philhellenic boom in the 19th century. Consequently Coubertin was extremely forwardlooking by fostering the following ideas which become the chosen perspectives of senses of Olympism:

-

1. Physical Education refers to Coubertin´s wish of revolutionizing the educational system by integrating a sporting component.

-

2. Fair-Play originating in English sports and to Coubertin being comparable to chivalry was supposed to become the moral credo of sporting life.

-

3. Internationalism describes Coubertin´s vision of bringing different cultures together on a common ground to foster international understanding.

-

4. Athletism refers to the demand of role model behavior by the athletes which were supposed to bring Olympism to life.

-

5. Eurythmie is a byword for the Cultural components of Olympism which should also remind of the festive character of ancient Olympic Games.

Based on these five catagories the first four Youth Olympic Games – YOG summer in Singapur and Nanjing (China) as well as YOG winter in Innsbruck (Austria) and Lillehammer (Norway) – are monitored according to the realisation of Olympism.

Results

-

1. In accordance with the first perspective of senses the YOG foster physical education in the educational system by organizing school programs in the host´s country. The YOG even go beyond Coubertin´s vision by also offering certain workshops and sessions to the athletes which give them the opportunity to educate themselves on sporting topics.

-

2. Fair-Play in the sporting world as well as the private life of the athletes is fostered by promoting equal rights for all nations and genders and by organizing workshops on global topics like global warming.

-

3. International understanding is stimulated by the mixed-nations-competitions as well as offers like the world culture village which enables the athletes to come together aside the sporting competition.

-

4. Athletism as a byword for the wish to develop Olympic ambassadors is integrated in the YOG in the persons of the Athlete role models which are chosen Olympic champions of the past helping to shape the Olympic champions of the future.

-

5. Eurythmie can not only be found in the borrowing of Olympic traditions of the adult Games like the torch relay but also in the additional culture program which sometimes even invites the participants to become creative themselves.

Most of the comparisons that were made so far were based on superficial and conceptual aspects.If you look closer and consider how the core areas are put into practice there are numerous differences between the visions of Coubertin and the concept of YOG with the exceptions of Fair-Play and peace movement.

The differences that are stated in the table above can be described as minor as they don‘t change the conceptual base of Olympism and are predominantly caused by contemporary developments.

A rather major difference lays within the sporting ethics: Coubertin´s Olympic sport is decidedly no high-level sport as he once stated:“Men (who) give up their whole existence to one particular sport (…) deprive it of all nobility and destroy the just equilibrium of man by making the muscles preponderate over the mind” (Coubertin see Segrave 2015 p. 196). The YOG on the contrary are closely bond to high level sports which necessarily includes specialisation. Moreover in the view of many of the young athletes that were participating in past editions of the YOG the Youth Games were primarily seen as a diving board to the sports world of adults.

Generally YOG offer a platform for social change and serve a better society – in this respect they meet the visions of Coubertin. However there is an elementary aspect that divide YOG and Coubertin´s Olympism: Coubertin´s sport should explicitly not be devoted to thoughts of profit – it serves only wholistic education and itself. In contrast the YOG orient themselves at high-level sports and invite coming professionals predominantly. Former IOC CEO Gilbert Felli stated: „Whether they go on to become sporting champions or end up mapping out careers in other fields we want the YOG participants to go back and be ambassadors in their communities embodying and promoting the Olympic spirit and values” (Slater 2009 p. 42). On the contrary the analyses of the passed YOG indicate that a major part of the athletes has only poor interest of CEP and of educating themselves on a deeper level about Olympic values but rather prioritize competition (Krieger et al. 2015). This may be followed by the risk of not achieving the pedagogical surplus that is supposed to be the distinguishing feature of the YOG.

To conclude to use YOG to foster Olympic education as it was one aim of the IOC is a step in the right direction. It is a test-field for innovative forms of competitions of multiple perspectivity of senses and social changes. However the effectiveness of the YOG in this sense has to be analysed. CEP-Outputs should be regarded equally to feats in sporting competitions to give a significant meaning to the educational visions of YOG.It should be kept in mind also: an ambassador of Olympism can be every person that lives the idea of Olympism. The educational efforts of the YOG may be more efficient if the Youth Games did not focus predominantly on the up-and-coming talents of the sporting world but rather consider adolescents with interests and ambitions on fostering the Olympic Spirit and values in their communities.

Список литературы Are the youth Olympic Games a modernized embodiment of Coubertin's olympism?

- Krieger, J. & Kristiansen, E. (2016). Ideology or reality? The awareness of Educational aims and activities amongst German and Norwegian participants of the first summer and winter Youth Olympic Games. Sport in Society, 19 (10), 1503-1517.

- Kurz, D. (2004). Von der Vielfalt sportlichen Sinns zu den padagogischen Perspektiven im Schulsport. In Neumann, P. & Balz. E. (Hrsg.), Mehrperspektivischer Spor-tunterricht - Orientierungen und Beispiele (S. 57 - 70). Schorndorf: Hofmann.

- Loland, S. (2015). Coubertin's ideology of Olympism from the perspective of the history of ideas. In Girginov, V. (Ed), Origins and revival of the modern Olympic Games. Series Olympic Studies, Vol. 1 (pp. 203 - 230). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Muller, N. (ed.) (2000). Pierre de Coubertin 1863-1937, Olympism - Selected Writings. Lausanne: IOC.

- Segrave, J. O. (2015). Towards a definition of Olympism. In Girginov, V. (Ed), Origins and revival of the modern Olympic Games. Series Olympic Studies, Vol. 1 (pp. 191 - 202). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Slater, M. (2009). Youthful outlook. Olympic review, 71, 26-49. Retrieved from https://library.olympic.org/De-fault/doc/SYRACUSE/173632/youthful-outlook-matt-slater?_lg=en-GB.

- Teetzel, S. J. (2015). Optimizing Olympic education: a comprehensive approach to understanding and teaching the philosophy of Olympism. In Girginov, V. (Ed.), Olympic Games through the lenses of discipline studies. Series Olympic Studies, Vol. 3 (pp. 279 - 296). Abingdon: Routledge.