Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory: One Hundred Years of Import Substitution

Автор: Pilyasov A.N., Buzhinskaya A.A., Saburov A.A.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Reviews and reports

Статья в выпуске: 61, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article is devoted to a retrospective analysis of the century-long history of the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory (ASF), the oldest enterprise in Russia with a full resource cycle of seaweed processing. The study is relevant in the context of modern challenges of import substitution and greening of industrial production. The subject of the study is the patterns and features of the evolution of an enterprise based on renewable natural resources. The object is the ASF, whose activities cover the full cycle, from seaweed harvesting to product release. The purpose of the study is to explain the long-term economic dynamics of the factory through the concept of of Kondratiev-Perez-Glazyev technological structures. For this purpose, the tasks of periodization of technological history, analysis of enterprise sustainability factors in times of crisis and identification of the specifics of its technological evolution were solved. The information base of the study includes documents of the State Archive of the Arkhangelsk Oblast, ASF reports, scientific publications and digital resources. The methodology is based on time series analysis, comparative and biographical analysis. The main results of the study are as follows: a periodization of the century-long economic history of ASF has been developed on the basis of the concept of technological formations; the evolution of the enterprise from handicraft to modern post-industrial production has been demonstrated; the factors of ASF sustainability in crisis periods, including the 1990s, due to the specificity of assets and innovative approaches have been identified; the contradictions between the production and resource base, which determined the need for technological transformation, have been revealed. During the discussion, the authors emphasize the importance of the transition to environmentally friendly technologies (plantation cultivation of seaweed) and the greening of production. The conclusions emphasize the unique role of ASF as an example of successful import substitution, transformation of technological structures and adaptation to the challenges of sustainable development.

Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory, technological structures, evolution, renewable resources, mining and processing subsystems, import substitution

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148332698

IDR: 148332698 | УДК: [338.45:639.29](470.11)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2025.61.290

Текст научной статьи Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory: One Hundred Years of Import Substitution

DOI:

Decree No. 529 of the President of the Russian Federation of June 18, 2024, “On Approval of

Priority Areas of Scientific and Technological Development and the List of Key Science-Intensive Technologies”, defined the transition to a highly productive and environmentally friendly agro- industrial and water management complex, as well as the development and implementation of rational nature management systems, as one of these key areas 1. This is fully consistent with the revolution in global biotechnology and life sciences that we are witnessing.

Meanwhile, we still know very little about the patterns and characteristics of the long-term economic dynamics (birth, formation and transformation) of economic structures that rely on the use of renewable natural resources and are currently the backbone of the agro-industrial, forestry and fishing sectors in Russian regions. The lack of such knowledge is particularly noticeable when compared to the numerous works of economists, historians and geographers on the long-term economic dynamics of regional enterprises in the oil, mining and coal industries.

In this regard, a retrospective analysis of the century-long history of the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory (ASF) is of exceptional interest. It is the oldest and the only Russian enterprise with a full resource cycle — from harvesting seaweed in the White Sea to its deep and diversified processing with the production and sale of hundreds of types of commercial products to consumers. The uniqueness of the enterprise has ensured the availability of long-term series of natural indicators of seaweed harvesting and processing, an extensive archive and an informative museum, which determine the possibility of systematic scientific research into the economic history of the factory.

The enterprise was originated by the challenges of import substitution, which our country faced at the beginning of the 20th century no less acutely than today. Therefore, looking back at the history of ASF is extremely relevant and instructive for us. Moreover, both the enterprise and the industry as a whole are on the threshold of significant changes, the course of which will be easier to predict and understand in the context of the factory’s century-long evolution.

The subject of our research is the patterns and characteristics of the development of the enterprise based on the use of renewable natural resources over a century, from the 1910s to the 2010s. The object of the research is the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory (ASF).

The purpose of the study is to explain the long-term economic dynamics of the ASF using the Kondratiev-Perez-Glazyev concept of technological structures, which necessitated the solution of several tasks:

-

• defining the boundaries and characteristics of the main periods in the factory’s technological history on the basis of graphs of the enterprise’s natural resource use dynamics (seaweed harvesting and production);

-

• identifying the reasons for the ASF’s survival during the crisis of the 1990s as a result of the significant specificity of all the enterprise’s assets (natural, labor, capital);

-

• generalizing the specifics of the enterprise’s technological evolution as a local-level entity compared to regional and interregional entities (e.g., aquaterritorial or mining area, province).

The novelty of this study lies in the fact that the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory (ASF) has never previously been the subject of a comprehensive analysis covering the entire period of its economic activity (for example, studies by K.P. Gemp [1] have covered specific periods). This analysis of the economic history of the factory is the first to be conducted in the context of the evolution of technological structures, constant technical innovations in seaweed harvesting and drying, methods for extracting useful biological substances from them, and the import substitution challenges faced by the country.

The information base for this work is Collection 1457 of the State Archive of the Arkhangelsk Oblast (SAAO), dedicated to the ASF: annual reports of the factory on its main activities, explanatory notes to it, reference materials, prefaces to collection inventories; scientific literature; materials from websites devoted to the activities of the ASF.

Research methodology and methods

The research methodology is based on the works of N. Kondratiev, K. Perez, S. Glazyev [2; 3; 4], as well as our own research on regional aspects of the evolution of technological structures in resource-rich areas of Magadan and Murmansk Oblasts, the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation as a whole [5, Pilyasov A.N.; 6, Pilyasov A.N., Kotov A.V.; 7, Pilyasov A.N., Tsukerman V.A.; 8, Pilyasov A.N., Tsukerman V.A.].

Research methods include analysis of time series of natural resource use, periodization method for identifying key stages of the factory’s activity, comparative analysis of the technological dynamics of enterprises with different resource profiles, individual enterprises and resource provinces as a whole, analysis of the biographies of the factory’s managers, etc.

Main results

-

1. The century-long economic history of the factory can be represented as a consistent technological evolution from the second to the fourth Kondratiev wave

Kondratiev’s long waves, lasting approximately half a century, reflect the economic realities and socio-cultural values of a particular technological and economic system. Their change, which is primarily associated with a radical shift in the dominant “anchor” technology used by industries that create the main added value in the economy, is always accompanied by the replacement of the previous production structure of society, scientific and technological paradigms, and socio-cultural concepts with new structures, paradigms, and values.

The second Kondratiev wave (…–1934)

In the Russian North, the beginning of the 20th century was marked by the emergence of the first “factory” industries, which inherited the characteristics of traditional, life-sustaining handicrafts of the 18th and 19th centuries. In our periodization, we will refer to this emerging technological structure as the second Kondratiev wave (K2).

During this time, the first seaweed “manufactory” appeared in Arkhangelsk — an iodine factory — a proto-industrial enterprise that operated de facto from 1914–1915, officially since January 1918. The technological process was relatively primitive and involved collecting washed-up laminaria along the shores and islands of the White Sea, hand-drying it on stands, burning the ash, and extracting iodine from it using manganese peroxide and sulfuric acid. “To obtain ash, seaweed is transported to the shore by horses, dried like hay, burned in piles, and stored in bags. From 100 poods of raw seaweed, 5–7 poods of ash are obtained” [9, Shurupova E.P., p. 167]. The emergence of the factory was directly linked to the imperatives of import substitution: iodine was needed for the wounded, and obtaining it from Germany, as before, was naturally impossible during the war with it [10, Stasenkov V.A., Studenov I.I., Novoselov A.P., p. 134].

The artisanal under-industrialization, difficulties of expensive delivery of seaweed resources from distant fields to Arkhangelsk [9, Shurupova E.P., p. 107; 11, Chirtsova M.G.], and high losses of iodine during transportation explain the instructive failure with the mothballing of the Arkhangelsk Iodine Factory in 1923 [10, Stasenkov V.A., Studenov I.I., Novoselov A.P., p. 236] and the partial relocation of its equipment to Zhizhgin Island [9, Shurupova E.P., p. 152], closer to the sources of iodine raw materials in the form of storm-driven luminaria drains, which this island was famous for due to its numerous bays.

This dichotomy — “closer to transport and trade routes to markets or closer to direct sources of raw materials?” — or, as it is commonly said in regional economics, location according to Losch-Christaller, i.e. based on demand and consumer market factors, or according to Weber, i.e. based on supply factors, unique resources — is uniquely characteristic of the second, artisanal Kondratiev period. Let us recall similar discussions on the “golden Kolyma”— where to build the city, the capital of the Kolyma region, nearby, directly at the gold mines in the Upper Kolyma basin, or as a seaport and transport hub in Nagaevo Bay on the Sea of Okhotsk?

For small, individual, artisanal production volumes, location directly at the sources of resource extraction is absolutely logical. In this regard, the relocation of the factory from Arkhangelsk to Zhizhgin Island precisely reinforced the artisanal, small-scale nature of the new seaweed production. On the other hand, as soon as there is a need for larger-scale, mass production aimed at a large external market, the advantages of proximity to the source of raw materials lose their former significance, and location in a large industrial and transport center, conveniently connected by transport routes to external consumers in the form of enterprises, exchanges, and companies, becomes the unconditional alternative.

Therefore, the failure of Arkhangelsk and then again, after the “Zhizhgin hesitations” (in 1923, on the instructions of the Arkhangelsk Provincial Council of National Economy, V.K. Nizovkin, I.V. Martsinovskiy, M.F. Smirnov, P.V. Ivanovskiy, I.A. Pavlov organized the industrial cooperative partnership “Belomorskoe iodine production” in Zhizhgin [9, Shurupova E.P., p. 152]), its acquisition of the functions of the location of an agar factory in 1933 should be considered not in the accepted interpretation of profitable/unprofitable (see, for example, the article by I.V. Martsinovskiy [12]), but as a reflection of the different patterns of location of small-scale artisanal production in the second Kondratiev wave and mass large-scale production in the industrial third Kondratiev wave. It was impossible to expand the scale of resource-super-productive Zhizhgin Island’s industry due to the objective new laws of industrial enterprise placement in the third Kondratiev wave. What mattered for this was not Zhizhgin’s proximity to other islands with massive storm-driven seaweed drains, but Arkhangelsk’s proximity to the large consumer markets, which demanded new, massive production volumes (and not the availability of firewood for drying seaweed with heat from a boiler house near Arkhangelsk and its absence on the industrial islands).

It is instructive to analyze the disruptions in the iodine industry: in 1929, the factory on Zhizh-gin was re-equipped to expand iodine production [13, Vinogradov V.A., p. 3]. In the following year, 1930, the Arkhangelsk Iodine Factory restarts, but in 1931–1932, it is mothballed again due to a lack of raw materials. Finally, in 1934, after a year of experimental work, it was re-launched as an agar factory, designed to substitute raw materials imported from Japan [10, p. 242]. This event marked the transition of the White Sea seaweed industry to the third technological stage, which increased the volumes from the first tons of iodine production at the Arkhangelsk and Zhizhgin iodine factories in the early 1930s to tens and hundreds of tons of agar, alginate, and mannitol production at the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory in the 1930s–1980s.

The third Kondratiev wave (1934–1996)

In our periodization, the third industrial Kondratiev cycle in the ASF lasted from 1934 to 1996, i.e. it stretched over 62 years (the standard duration is half a century). On the other hand, the second “artisanal” cycle, which was based on the extraction of iodine from laminaria, was compressed to approximately 20 years (1914–1933). Iodine production was interrupted by the discovery in the 1920s of more cost-effective methods of extracting it from mineral waters rather than from seaweed [10, p. 241]. These patterns were characteristic of many regions of the North and the Arctic, where the transition to mass industrialization in the 1930s led to the rapid displacement of artisanal production of the second Kondratiev wave that had just begun in the last years of Tsarist Russia (in Kolyma — gold mining from placers, in the White Sea region — iodine extraction from laminaria). The third industrial “conveyor-belt” techno-economic order, on the contrary, was significantly delayed, even as the preconditions for the transition to the fourth and fifth Kondratiev waves, based on pipeline and air transport, and then on digital and biotechnology, telecommunications, and total computerization, were already developing worldwide.

It is essential to distinguish between the second and third Kondratiev waves precisely in terms of resource specialization. The second wave was based on artisanal (manual extraction and processing), i.e. small-scale iodine production, which in the late 1920s began to take on new mechanized forms (mechanical dredging of seaweed, rather than manual, as before [13, Vinogradov V.A., p. 3]). The third wave was based on mass (large-scale) mechanized production of agar at a new agar facility.

The type of seaweed used, the resource extracted from it (i.e., the enterprise’s resource specialization), the technology applied, and the territorial structure of the seaweed industry changed. After experiments in the early 1930s, from 1935 onwards, instead of laminaria, the new main resource for the factory became ahnfeltia, which was intended to replace the imported Japanese agar extracted from it (used as a natural thickener for the production of jam, soufflé, pastille, marmalade, and other confectionery products, which is why the factory was part of the State Trust for the Glue and Gelatin Industry). Instead of relying primarily on storm seaweed drains, there was an emphasis on harvesting (first manually, then mechanically) growing/cut seaweed. The possibilities for mechanizing all production processes and transporting harvested seaweed raw materials to the factory for processing arose and gradually expanded. Innovative technologies for processing seaweed and producing new types of products were developed. The technology for obtaining agar from ahnfeltia was the result of the work of a specially created Seaweed Laboratory in the late 1920s [1, Gemp K.P., p. 8].

The factory, which later became a combine, began generating its own innovations in harvesting, drying, storage, and processing — a process of innovation localization took place (in the second Kondratiev wave, the first knowledge of seaweed resources obtained from scientific expeditions from St. Petersburg was used in production). The third Kondratiev wave at the factory was not associated with just one resource specialization: foreign market conditions and demand for seaweed products, import substitution imperatives, and the available reserves of seaweed resources in the White Sea determined multiple changes in the dominant specialization: first, agar from ahn-feltia, then middlings from fucus, then alginate from laminaria, then various pharmaceutical products from laminaria.

The pioneering stage of launching a new resource frontier, as always happens and as subsequent events showed, was a very fragile stage with several restarts of the enterprise: the first launch of the new resource frontier took place in the 1934–1940s, then, after a de facto shutdown during the war years, the restart took place in 1945–1954. At the same time, until 1943 [1, Gemp K.P., p. 8], along with the production of new agar, the production of the old iodine, inherited from the second Kondratiev wave, continued by inertia. This is very similar to the preservation of placer gold mining in Kolyma until the 1940s, when mechanized industrial equipment had already been introduced at most of the Dalstroy mining departments.

The pioneering stage of economic development is usually characterized by extraordinary personalities who manage it and therefore remain in the historical annals of the enterprise, industrial region, or province for a long time. For the Arkhangelsk Agar Factory, such a legendary figure was its first director (1933–1937), N.D. Grigoryev, who established the new production with the help of a small team (about 75 people), consisting mainly of women 2.

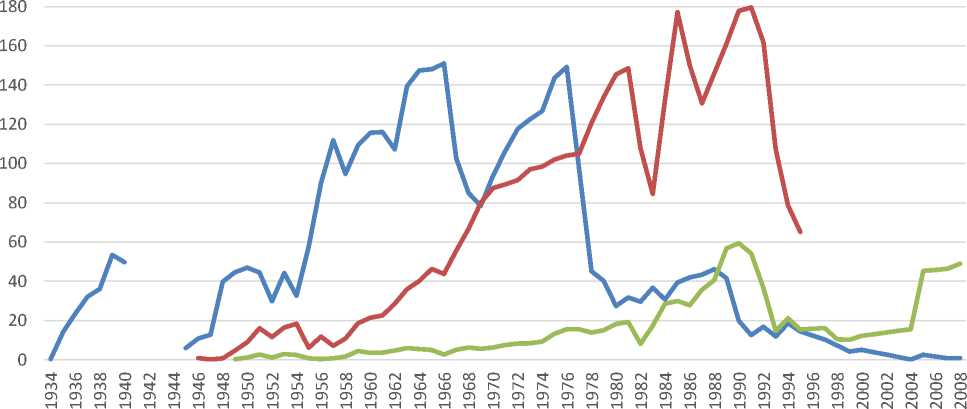

Despite the objective difficulties always associated with the pioneering stage of enterprise development 3 and the high annual amplitude of production, the factory quickly moved from the production of first tons of agar to tens of tons (53 tons in 1939), thereby exceeding substantially the volume of iodine production from laminaria in the 1910s and 1920s in the second Kondratiev wave. Although the creation of the agar factory initiated a long era of agar production at the enterprise, in the mid-1940s (Fig. 1), the first diversification of production occurred through the manufacturing of alginate from laminaria, which was used in the textile, paint, and rubber industries. Even for the vertical take-off of a new frontier resource production, it is always characteristic to simultaneously improve other, non-core types of industry, which over time can become a new frontier and replace the previous one.

^ ■ мвAgar, tonnes ^^^^^мAlginate, tonnes ^^^^^м Mannitol, tonnes

Fig. 1. Dynamics of agar, alginate, and mannitol production at the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory, t 4.

During the war years, the factory changed its focus, temporarily switching to the production of laminaria powder for making seaweed soup stock for residents of besieged Leningrad and the Arkhangelsk Oblast [10, p. 242]. Therefore, in 1945, the first frontier phase of the enterprise’s restart essentially began again. However, it would be incorrect to assume that this was a simple relaunch of pre-war agar production.

In fact, pre-war and post-war productions were two different frontier eras. The pre-war factory was managed by the exotic state trust “Kleizheprom”. After the war, it was transferred to the state trust “Rosglavkonditer”, and in 1947 — to the fishing industry trust “Sevryba” 5, which emphasized the commonality of seaweed and fish harvesting in the post-war period of active mechanization of all major production processes.

Indirect, but very important confirmation of our correctness in identifying the 1945–1954 period as a new (industrial) start of a long technological wave in the graphs of nature use dynamics (primarily basic and agar) is the fact that F.A. Bryzgunov was the factory’s director during these years (1938–1941 and 1946–1953). On the one hand, he ensured the continuity of the factory’s first prewar and second post-war agar production. He quickly restored production after the Great Patriotic War. On the other hand, he strengthened a new (pharmaceutical and technical) direction for the factory — the production of sodium alginate and mannitol (the former mannitol factory was destroyed during the war) from laminaria, which eventually became the mainstay of the factory. It began producing technical sodium alginate in 1946 (food-grade alginate in 1955) and mannitol in 1949 (pure mannitol for analysis in 1959). By that time, the factory employed over one hundred people, making it a medium-sized enterprise.

After the initial phase of establishing the new agar frontier, which was specifically launched twice at the factory — before and after the war, there was a phase of aggressive investment and extensive experiments to develop methods for mechanizing the extraction and processing. This stage lasted for more than two decades, from 1954 to 1977, and ensured a significant increase in indicators across the entire range of production. It should be noted that this phase may proceed differently depending on the state of the resource base. For example, in the Kolyma gold-bearing regions, after quickly reaching its peak in the first phase, aggressive investment in the second phase was unable to break the trend of decline of the new province, despite various efforts. As a result, the decline in gold production continued throughout the entire period against the backdrop of experiments to expand the resource base at the expense of adding other metals, using new technologies such as new models of industrial equipment, etc.

On the other hand, at the Arkhangelsk factory, which essentially monopolized the White Sea seaweed resource base, aggressive investment in the second phase ensured an increase in seaweed harvesting volumes and the production of agar, sodium alginate, and mannitol.

The phase of aggressive investment was marked by the mass mechanization of all production processes. In harvesting, this meant concentrating on the most productive section of the Solovetsky Islands and expanding the enterprise’s self-propelled fleet to a hundred units 6. A single area of mechanized dredging for laminaria from barges/boats with winches accounted for up to 35% of its total harvest 7. A self-propelled mechanical dredger of the “Nepreryvka” type was used to extract laminaria at depths of up to 12 m 8. Mechanical dredgers of the “Pauk” type were used in areas with gravel and rocky soil.

The preparation stage included mechanized pressing of harvested seaweed into bales, previously into nets. New drying principles and dryers were introduced for drying seaweed 9: a workshop for artificial drying of fucus and laminaria was built, and a double-drum steam dryer was purchased in Estonia. A new continuously operating KALEV-type apparatus was used for boiling seaweed. As a result of the reconstruction of the mannitol department in 1973 10, crystallizers, heat exchangers, evaporative bowls, cartridge filters, centrifuges and other necessary equipment appeared here, which doubled the annual production volume 11. The total mechanization of production processes reduced dependence on manual labor, and for the first time, the factory experienced a reduction in the number of workers.

During the phase of aggressive investment (no later than 1958), an experimental group was created at the factory, which for a long time served as its local innovation system: it developed special dredger models for the enterprise, taking into account the characteristics of the White Sea seabed, an underwater industrial installation for cutting seaweed, carried out the adjustment of equipment received from suppliers, and collected rationalization proposals from the plant’s employees.

The beginning of the aggressive investment phase marked a period of centralization of the factory’s functions as the sole, monopolistic entity for seaweed economic activity in the White Sea. In 1955, the Zhizhgin Agar Factory became part of the Arkhangelsk Agar Factory as a workshop 12. In 1960, a workshop was launched on the Solovetsky Islands for processing seaweed into agar and producing seaweed powder 13. In 1964, the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory was established on the basis of the Arkhangelsk Agar Factory. The new name emphasized the resource diversity of the main products (agar, sodium alginate, mannitol).

In the context of the enterprise’s growth based on the mechanization of key production processes and the already apparent depletion of ahnfeltia resources [10, p. 243], on which the production of agar as the main, absolutely dominant type of product was based (i.e. it was impossible to achieve economies of scale in agar production), the decision to combine several resource chains was entirely justified. By the end of the 1950s, the formerly single-profile factory had become a diversified enterprise with two internal workshops — an agar workshop and an alginate workshop (with boiling, alginate, and mannitol sections) 14, serving several consumer groups: agar for the confectionery and microbiological industries; mannitol for the pharmaceutical industry; sodium alginate and laminaria powder for the textile industry.

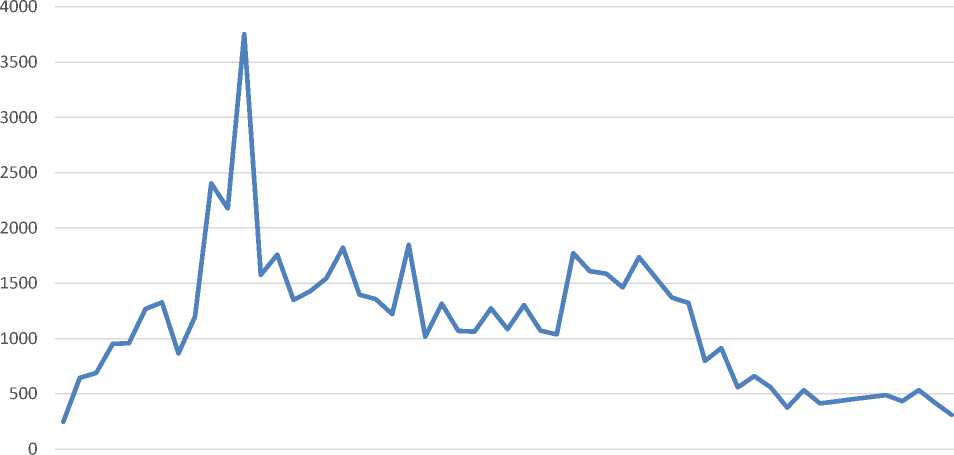

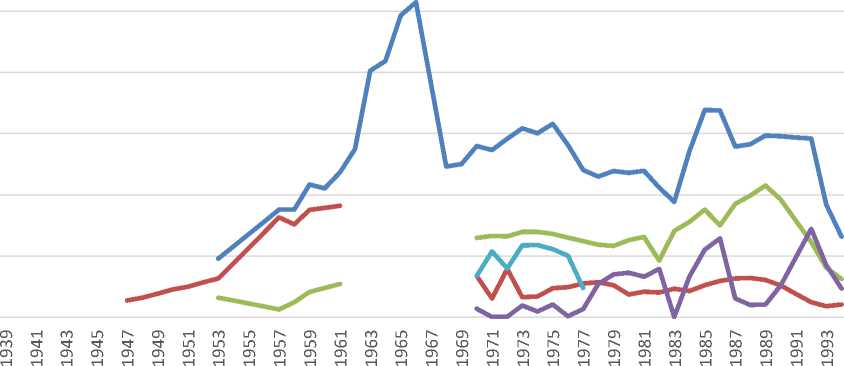

The dynamics of the annual amount of seaweed received for processing (Fig. 2) clearly distinguish two periods in the factory’s operation: 1) exponential growth in 1954–1965, reaching a peak of 3,754 tons in 1965; and 2) a sharp decline in 1965–1977, followed by stabilization at approximately 1,200–1,300 tons by the end of the period in 1977. The graph of consumption of all types of seaweed shows a similar pattern, with the peak value of 2,574 in 1966 (Fig. 3).

^^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Fig. 2. Dynamics of total seaweed harvesting volumes (own and purchased under contracts), t.

^ ■ MBTotal consumption, tonnes ^^^^^BAnfeltia, tonnes

« ■■■■■■ в Kelp, tonnes

« ■■■■■ вFucus, tonnes

^^^^^^ Furcellaria, tonnes

Fig. 3. Consumption of all types of seaweed for production, t.

What happened between 1963 and 1967, when the volume of received and consumed seaweed increased sharply? At that time, massive production of seaweed powder and seaweed middlings was carried out. Seaweed powder was produced in the powder workshop on Solovki from laminaria (dry laminaria is crushed, dried, then crushed again into middlings and ground into powder in a vibratory mill) 15 and was used in the textile industry in the Ivanovo Oblast. Middlings were produced from fucus and supplied to mixed feed factories.

This short-term experiment in mass production of low-value end products was similar to the experiment with mass planting of corn in risky farming zones, which was launched in the country at the same time and was just as quickly abandoned. After a short period of frontier expansion, the production of middlings and powder was significantly reduced by the end of the period, and only fucus middlings continued to be produced.

However, this short experiment with the production of a new mass product, which accounted for about two-thirds of the factory’s total output, reflected a general search for a new sustainable specialization that was responsive to the new possibilities of total mechanization of all production processes. It was no coincidence that it affected laminaria and fucus, rather than ahnfeltia: the characteristics of both laminaria and fucus allowed them to be easily involved in mass harvesting and processing. On the other hand, the scattered growth of ahnfeltia [10, p. 247–249], with the constant threat of depletion, made it difficult to take advantage of the possibilities of mass mechanization of harvesting, for example, by mowing from self-propelled barges. Different types of seaweed in the White Sea were not equal in terms of their readiness to be mechanized.

In the 1960s, K.P. Gemp first wrote about the apparent depletion of ahnfeltia stocks in the White Sea [14, p. 191]. This was facilitated by many years of active exploitation of nearby shallow areas by hand dredging, more remote areas — by mechanical “Pauk” dredges, and the deepest areas, where dredges cannot operate, — by divers. The search for a solution to the emerging local environmental crisis involved switching to storm-driven ahnfeltia drains collection, limiting the harvesting of ahnfeltia to hand dredging 16, cultivating ahnfeltia artificially in collaboration with SevPINRO [15, Gemp K.P., p. 232] (the experiments were deemed unsuccessful), and purchasing Baltic furcellaria (a technology for producing agar from furcellin was developed in 1968). At the end of the third industrial wave, the restrictions imposed were intensified: in 1987, according to the conclusion of the Northern Branch of PINRO, the seaweed industry had reached the limits of its development, exhausting the permissible limit for the extraction of resources from the White Sea. Even on the factory’s new frontier near the Solovetsky Islands, a limit on laminaria harvesting was set at 950 tons instead of the previous 2,400 tons 17.

This raises the question of the nature of the first and second peaks in agar production in 1966 and 1976 (Fig. 1). While the first peak reflected the monopoly dominance of agar in the factory’s final output —sodium alginate production from laminaria was still insignificant (44 tons) — the second peak occurred when alginate production had already reached 104 tons, significantly less than agar production in terms of volume. At the first peak, the agar produced was intended for the microbiological industry, and at the second peak, due to its production from Baltic furcellaria of poorer quality (purchases were made in the short period from 1969 to 1977 and ensured growth in production), it was intended for the food industry. At the beginning of the next phase of the “golden age synergy”, sodium alginate production from laminaria (with the potential for a mass resource base) surpassed the rapidly declining production of agar.

This successful period for the enterprise during the second phase of the third Kondratiev industrial cycle ended with the loss of its legal and financial independence due to its entry into the Arkhangelskrybprom production association in 1976 18. At the same time, the factory’s director, A.I. Potrokhova, left for a promotion. The most important outcome of this phase was that the reliance on mass production, characteristic of the period of total industrialization, made a shift in the enterprise’s resource focus inevitable. This mass production could now be ensured by laminaria, not ahn-feltia. The era of agar dominance came to an end, and the era of laminaria product dominance began at the factory.

The next phase of the third Kondratiev cycle at the factory was in the period from 1977 to 1990. Some experts call it the factory’s “golden age”, “the best years of exploration and implementation” [16, Bokova E.M., Titov V.M.]. During this period, the country’s demand for seaweed products increased by several times [17, Semenova R.P., p. 38], and the factory strengthened its position through the mass production of technical and then food-grade sodium alginate from laminaria and fucus, mannitol, agar, dietary supplements, and other products for light, food, and pharmaceutical industries.

In 1979, the plant was renamed the Arkhangelsk Experimental Seaweed Factory 19, since the share of experimental and testing work in the total gross output amounted to more than 90%. The only full-cycle industrial seaweed enterprise in the country became an experimental base for extensive innovative research by chemists, technologists, and engineers not only from the factory itself, but from across the country. Broad scientific partnerships were established between the factory’s specialists and technologists from the Plekhanov Institute in Moscow, the All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Medical Polymers, the Leningrad Scientific and Production Association Fitolon, the All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Chemical Technology of Medicines, and other chemical, technological, pharmaceutical, and biotechnological enterprises [17, p. 39].

There was a clear shift in focus away from engineering and mechanical innovations towards innovations in chemical reactions and processes, which are becoming primary, with technical modernization of equipment being carried out to support them. For example, more advanced extraction systems for increasing product output, which entail the modernization of the equipment.

The accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986 gave a powerful impetus to research work at the factory and a significant expansion in the production of “by-products”. Unexpected anti-radiation properties of alginates were discovered, which “ensure a 75% reduction in the level of cesium and strontium in body tissues and specifically affect the vital systems of the body most affected by radiation” 20. This became the impetus for the start of production of the first dietary supplements: radioprotective preparations “Algigel”, “Canalgat”, as well as “Inhibitor”, “Laminaria Extract”, “Laminaria Concentrate”, “Laminit”, etc. [18, Varfolomeev Yu.A., Bogdanovich N.I., Bokova E.M., p. 158]. The director of the factory (1984–1990), A.M. Kostomarov, initiated the production of new products for the perfume, soap and cosmetics industries from mannitol production waste.

During this period, two lines coexisted in the enterprise’s activities: a new, “capillary” line for expanded production of small-batch, high-value new products for medical, pharmaceutical, and perfumery purposes, reinforced by the factory’s new pilot status; and, simultaneously, a traditional line for mass, large-scale production of technical alginate, mannitol, and agar for the needs of other industrial enterprises in the country, which was accentuated by the completion of the new factory in 1982 [19, Polovnikov S.Ya., p. 91].

The initiative to build it was put forward back in the late 1960s [19, Polovnikov S.Ya., p. 90], that is, in a completely different economic era — at the stage of aggressive investment during the third Kondratiev wave. This gives rise to a dramatic contradiction of this period: the largest production facility, commissioned during the “golden age of the factory”, was actually timed to appear much earlier, in the early 1970s, during a period of quantitative expansion and total mechanization of production processes. Instead, it emerged at a time when the focus was not on mechanical expansion, but rather on the chemical “deepening” (intensification) of technological and production processes.

The launch of the first and second phases of the new factory (construction began in 1978 and was completed in 1982, with the first phase commissioned at the end of 1981 and the second one — at the end of 1983) [19, Polovnikov S.Ya., pp. 90–92] raised the planned output to 300 tons of sodium alginate from laminaria, 200 tons of sodium alginate from fucus, 50 tons of mannitol, and 39 tons of agar from ahnfeltia per year [19, Polovnikov S. Ya., pp. 91–92]. However, the factory was unable to actually produce these volumes.

Total sodium alginate production at the factory in the 1977–1990s (technical and food grade) never exceeded 180 tons, which was almost three times lower than the capacity of the first and second phase alginate workshops. However, the graph showing the 40-year dynamics of alginate production at the factory from 1946 to 1986–1988 looks very impressive, demonstrating almost continuous growth.

The new factory’s mannitol production capacity was calculated at 50 tons [19, Polovnikov S.Ya., p. 91], and demand for it in the country in the 1980s was stable in the pharmaceutical and medical industries (used as an osmotic diuretic, in the process of blood preservation, as a cryoprotectant when freezing erythrocytes, for the production of mannitol solution, which is indispensable in heart surgery and for cerebral edema), as well as in the food industry (used as a sweetener and stabilizer in the production of dietary products and sugar substitutes). Therefore, the requirements to meet the planned targets were very strict, and the factory wrote annual explanations of the reasons for chronic failure to fulfill planned targets: during the entire available observation period, it only “reached” this target three times (1989121991, Fig. 5).

As for the production of agar from ahnfeltia, the capacity of the new factory was more realistically estimated at 39 tons [19, Polovnikov S.Ya., p. 92], which was achieved for almost the entire period up to 1990 (Fig. 1).

The golden age of the factory ended with its granting legal entity status with financial independence in 1989, which marked the beginning of a new period of “freewheeling”. Apparently, there is a certain pattern in the fact that in the first and last phases of the Kondratiev cycle, the enterprise has the rights of legal and financial independence (autonomy): in the first frontier stage — because the future is uncertain, and the risks are entirely on the enterprise; in the final crisis stage — because the future is problematic, and the enterprise has to cope on its own, without relying on higher authorities. Only in the prosperous second and third phases, the enterprise has the high-level supervision of central administrations, state trusts, and agencies that “extort money” from it.

The final phase of the third Kondratiev wave, which can be called the “crisis twilight”, began in 1990–1996 against the backdrop of a nationwide economic and political crisis. During this period, the most important task was to preserve this unique enterprise.

Obviously, such a radical transformation was accompanied by a significant reduction in the output of the enterprise’s traditional products, for which, on the one hand, there was a shortage of raw materials, and on the other, there were no longer traditional consumers. For example, the volume of seaweed harvested by the end of the period had fallen threefold, from 1,500+ tons in the early 1990s to 500 tons in 1995–1996, fourfold for fucus, twofold for ahnfeltia, and one and a half times for laminaria. Such radical reductions were naturally accompanied by mass layoffs.

Pressure from cheap Chinese competitors 21 (for example, synthetic sodium alginate substitutes from China) forced the factory to stop production of traditional varieties and switch to new ones. Agar production was reduced by half, sodium alginate — by three times, and mannitol — by four times. The factory developed a special program for the production of consumer goods: medical products, dietary supplements, cosmetics, confectionery, and pharmaceuticals, for which the technological equipment was retooled.

The fourth Kondratiev wave (1996-nowadays)

An analysis of the development of the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory during the third industrial wave allows us to formulate a fundamental contradiction between the available resource base and the enterprise’s production capabilities. The factory began its operations as a new, small entity on the seaweed resource frontier (agar from ahnfeltia) and initially had no resource constraints on its growth. However, as it inevitably expanded (in terms of personnel, production, harvesting areas), it began to encounter limitations in the availability of easily accessible and profitable resource base. The peak indicators of seaweed harvesting, ensured by the transition from manual harvesting of laminaria and ahnfeltia and the collection of storm-driven fucus and ahnfeltia drains to dredging (including) mechanized harvesting, subsequently led to a collapse in production due to the destruction of bottom ecosystems. The rate of growth in production exceeded the rate of natural recovery. It is impossible to resolve the described contradiction within the natural-production system of the third Kondratiev wave. A way out is required in order to start all over again, but within the new technological framework of the fourth Kondratiev wave, based on the ideology of environmentally friendly technologies and solutions (for example, the transition to controlled plantation seaweed farming).

The crisis of the first half of the 1990s accelerated the long-awaited but constantly postponed transition of the country, its enterprises and regions to a new post-industrial technological structure, the basic features of which are environmentally friendly technologies, human-centered production, and ecological priorities in economic activity. As early as the 1980s, it was obvious to enterprise management that the new main path of development was linked to the production of “by-products” oriented not towards the economy of legal and economic entities, but towards the economy of individuals, i.e. the demand of individual consumers for high-quality natural cosmetics, diabetic products, medicinal raw materials, food supplements, etc. Radical market reforms in the country facilitated the transition to this trend by dismantling the rigid planning system that had been reproducing outdated technological solutions for decades. This created conditions for searching for alternative non-governmental financing for the implementation of new technological schemes for seaweed processing, first through own funds and then through borrowed ones (credit and investment).

It can be said that for the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory, this meant a return to the artisanal values of a century ago, but at a new level of modern production capabilities. In economic terms, the effect of economies of scale and volume of operations was replaced by the effect of small-volume commodity groups, i.e. the effect of diversification characteristic of a medium-sized seaweed business, which is what the ASF is today.

The first phase of the new cycle was unfolding over 20 years (1996–2016) and was characterized by a long launch of the frontier on new technology/resources, although its initial prerequisites were already outlined in the final stages of the previous wave. Within this phase, two periods can be distinguished: 1) disjointed organizational and technological transformations in the early years — as the priority to ensure the survival of a unique enterprise in aggressive external environment remained; 2) systematic work to modernize the factory to meet the requirements of the new order — in the 2000s and 2010s, under the leadership of E.M. Bokova.

In 1996, the factory received the status of a state unitary enterprise. From the three types of intermediate products (agar, alginate, mannitol) that were canonical for the third Kondratiev wave and were intended to meet the demand of other economic enterprises, it moved on to the production of end products for individual consumers. The factory’s new products included the food supplement “Laminal”, “Dessertnoe” jelly, “Laminaria” cream 22, “Laminaria” shampoo, the food supplement “Fucus”, diabetic products, dietary supplements, and medications 23.

In 2002, the plant was transformed into the Federal State Unitary Enterprise “Arkhangelsk Experimental Seaweed Factory” (FSUE “AESF”) 24, which meant that it bypassed the first wave of privatization and retained its original state status, under which it operated until the mid-2010s. During this period, it was possible to stabilize the production of its core products (significant growth was achieved for mannitol), to expand the range of products (to over 50 items) for perfumery, cosmetics, medicine, healthcare, food and agriculture, to establish a new confectionery production facility and to implement successful marketing of the factory’s new products.

The environmental agenda became a new frontier for the enterprise: the factory focused on eco-products and environmentally friendly technologies. The relaunch of the factory was facilitated by E.M. Bokova, who had worked for a long time as a process engineer at the plant, including at the remote Solovetsky site, and therefore had a very good understanding of the potential of the enterprise’s resources, production and personnel capabilities in the context of a radical transformation of its specialization (a new frontier in biopharmaceutical products from seaweed). At the end of the period, in 2016, the enterprise became a private joint-stock company, OJSC “AESF”, due to the sale of 100% of the state-owned stake to a new owner 25.

Summing up the results of the first phase of Kondratiev’s post-industrial cycle, it should be noted that its traditional main objective — entering a new development trajectory by creating new seaweed processing lines — was achieved. At the same time, it is regrettable that this process took too long (two decades). This was undoubtedly due to delays in the privatization process, protracted transition of the enterprise from one form of state ownership to another (SUE-FSUE-OJSC with 100% state participation and the Russian Federation as its state founder). However, we cannot imagine all the risks posed to the enterprise by rapid privatization: despite its monopoly status as the only seaweed factory, the small plant (as of 2024, it employs 76 people 26) , could simply disappear (in the 1990s, numerous larger enterprises were subdivided, disintegrated, became targets of raider attacks and endless reorganizations).

The second phase of the fourth Kondratiev wave, characterized by aggressive investment in previously discovered new resource / commodity frontiers, achieving mass production volumes, and vigorous diversification of the product range, began in 2016 and continues to these days.

According to the SPARK database, “in 2016, the factory underwent privatization, and in 2017, it was acquired by a group of Moscow investors”. These changes led to an updated development strategy for the enterprise and the attraction of additional investments, which contributed to a threefold increase in its revenue over the next two years. The new owner’s priorities were to maintain the factory’s traditional production methods while modernizing its technology and making it more environmentally friendly: gasification, technical re-equipment, modernization of old equipment and purchase of new one, environmentally friendly seaweed harvesting, and creation of a wide range of new products. These priorities were clearly outlined in 2022 in an interview with the ASF Director Artem Ivanov 27.

The new systemic investment project for the factory’s modernization was estimated at half a billion rubles, with an emphasis on budget financing (federal and regional). The enterprise began promoting its products on major online platforms such as Ozon, Wildberries, and Yandex.Market, through its official online store, and in offline stores in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Arkhangelsk, Severodvinsk, Kotlas, Kaluga, Ryazan, and Petrozavodsk 28.

At the same time, and somewhat unexpectedly from the perspective of the factory’s traditional activities, in 2019, a small investment project was implemented on behalf of the ASF to build a mini fish-processing plant for cod, haddock, and other types of fish, “which made it possible to expand the product range and increase processing volumes” 29.

In 2022, control over the factory was acquired by a new owner, PJSC Inarktika 30. Since In-arktika is the Russia’s largest commercial fish farming (aquaculture) company, it can be assumed that the strategy of radically transforming the factory’s activities into aquaculture will become the company’s main investment priority, while strengthening and expanding the modern biotechnological profile of its products.

It should be remembered that PINRO’s first attempts at plantation cultivation of ahnfeltia and laminaria were made back in the 1960s, but they were unsuccessful at the time because they contradicted the main direction of the third Kondratiev industrial cycle: mechanization of production processes, increased production of technical alginates and food-grade agar at any cost, deliberately ignoring the resulting environmental limitations.

In the spirit of the environmentally friendly solutions of the fourth Kondratiev wave, the aquaculture investment priority [20, Stasenkov V.A., Zelenkov V.M., Antonova V.P. et al., p. 52] of the new owner of the ASF seems appropriate and more convincing than the ecologically beautiful ro-manticization of the archaic Pomor activities (manual harvesting, natural drying, etc.) of the previous owner. Aquaculture and seaweed cultivation are considered by the leading countries in the industry as a global strategic development trend for the coming decades [21, Albrecht M.A.; 22, Stévant P., Rebours C.; 23, Veenhof R.J., Burrows M.T., Hughes A.D. et al.; 24, Duarte C.M., Bruhn A., Krause-Jensen D.; 25, Orbeta M.L.G., Digal L.N., Astronomo I.J.T. et al.; 26, Chopin T., Tacon A.G.J.; 27, Chung I.K., Sondak C.F.A., Beardall J.; 28, Kim J., Stekoll M., Yarish C.]. This means that the new owner will have to find pioneering and cost-effective technical solutions for plantation cultivation of seaweed in the specific conditions of the White Sea, effective “environmentally friendly” mass drying of seaweed, and preserving a reasonable share of traditional harvesting of wild seaweed in new nature-compatible forms. After all, for example, plantation cultivation of cranberries and blueberries does not negate the value and necessity of traditional harvesting of wild berries.

It can be expected that the fourth Kondratiev cycle for the ASF will be completed in the middle of the 21st century, and a required radical paradigm shift in the White Sea seaweed farming industry will occur in the near future. This will reflect not the superficial environmental imperatives of the existing industrial production, but rather its complete reformatting in line with new, environmentally friendly requirements. As the experience of the factory’s century-long development shows, solving the environmental problems of seaweed resource depletion within the industrial economic model is impossible; its complete technological transformation is required, in line with the values and technical capabilities of the new economic philosophy of the fourth Kondratiev wave. During all these years, the main imperative in the enterprise’s activities will remain the idea of import substitution with its own high-quality products that are in demand on the Russian market.

Summarizing the retrospective dynamics of the development of the factory’s production system in the third industrial wave and the beginning of the fourth Kondratiev wave, we can understand the role of innovations as an attempt to balance the dynamics of the extractive and manufacturing subsystems. At each phase of the Kondratiev wave, an imbalance arises between the extractive and processing subsystems. The extractive subsystem initially takes the lead, and this is the frontier stage; the manufacturing subsystem cannot keep up with it and becomes a “brake” on the growth of the new frontier. During this period, the innovation process intensifies in the processing subsystem.

Then, as signs of initial depletion appear and pioneer development resources (frontier) enter a stage of stabilization without sharp growth, the resource base begins to slow down the development of the enterprise, while the processing system has already gained momentum. This is the stage of investment expansion. There is a demand for a sharp enlargement of the harvesting area. Here, again, the innovation process succors — a cascade of innovations in resource harvesting methods appears.

The third phase signifies a certain harmony between the volumes of seaweed harvested and the volumes of various types of end products extracted from it. Then, in the fourth stage, this balance is disrupted again, and the rapid depletion of the resource base becomes an obstacle to maintaining the same production level. This raises the question of a change in the production structure, which, in essence, acts as a change in the entire previous industrial paradigm. Innovations created during this crisis period become the “fuel” for the development of the enterprise in the new long wave of the fourth Kondratiev cycle.

2. The reason for the factory’s survival in the 1990s as a result of the positive effect of the specificity of its assets

The reasons for the resilience of this medium-sized seaweed processing factory (while much larger ones were disintegrated and disappeared) during the crisis of the 1990s are rooted, among other things, in the history of its creation. The location of the plant during the dramatic years of wars and revolutions at the end of the second decade of the 20th century in Arkhangelsk, rather than in neighboring Murmansk and Petrozavodsk, is both natural and paradoxical. The availability of seaweed resources — laminaria, ahnfeltia, and focus — was by no means the decisive factor. The resource base itself did not give Arkhangelsk a clear advantage, since Murmansk and Karelian fishing collective farms supplied the Arkhangelsk factory with scarce ahnfeltia for agar production for many years afterwards. Apparently, both Karelia and the Murmansk Oblast had their own resources of iodine-rich laminaria.

A more important factor was the successful and rare combination of, on the one hand, already established industrial innovations and culture and, on the other hand, preserved maritime traditions of fishing vessel construction and repair. Neither Murmansk nor Petrozavodsk had such a combination of innovations and traditions. These circumstances explain the emergence in Arkhangelsk of the first in the White Sea region iodine factory, based on laminaria resources.

The factory could disappear during the crisis of the 1990s, like hundreds of other, including larger, industrial enterprises in Russia. However, this did not happen, as we believe, due to the highly specific nature of its resource, production, and labor assets, which determined the strong integration of the extraction and processing sectors, the commitment of the remaining employees to the plant, and the close ties of all links in the production system (extraction, processing, and marketing) with local “seaweed” science. The monopoly position of the factory in the country and in the White Sea basin as the only enterprise carrying out the full cycle of seaweed processing, from extraction to deep processing and the release of the final product, was also of great importance. Another significant factor was the reliance on its own resources, which was strengthened during the crisis years: harvesting of seaweed raw materials with its own small fleet, and the historically established processing along three main lines: agar from ahnfeltia, mannitol and sodium alginate from laminaria. In the 1990s, the factory began building its own fishing boats 31, purchased a dry cargo ship to supply the harvesting areas with all necessary equipment [17, Semenova R.P., p. 39], and built its own boiler house to ensure a constant supply of process steam 32. The sustainability of the factory’s autonomous production system only strengthened in the 1990s.

Specific seaweed assets required specialized technological equipment for harvesting and processing, which the factory needed as the only enterprise in the country consolidating all stages of the production process — from harvesting seaweed to selling it to consumers. This meant that such equipment had to be unique in many cases, i.e. to be produced in a single copy or a “singlepiece”. So, constant close interaction between the factory’s employees and the suppliers of such equipment was required. This suggests that much of this equipment was produced by the factory itself (for example, in 2020, the factory, together with colleagues from PINRO, developed a special mower for the mechanized harvesting of seaweed in the conditions of the White Sea 33) , or was obtained from geographically close industrial enterprises in Arkhangelsk and Leningrad. Only continuous personal communication, with a constant exchange of tacit knowledge between consumers (represented by the factory’s employees) and suppliers (represented by employees of supplier companies), could ensure the alignment of the factory’s requirements and suppliers’ proposals with the necessary “subtle” parameters.

However, a similarly close relationship existed between the factory’s consumers and its technologists, ensuring the precise “fine-tuning” of the chemical engineering process in the interests of the consumer enterprises (the largest of which were the textile enterprises in Ivanovo). There was also close cooperation through regular business trips between the factory’s research and experimental departments and the research institutes in the light, pharmaceutical and food industries.

3. Features of the local level of a resource enterprise when applying the technological wave concept

Previous experience in conducting deep retrospective “technological wave” studies for Russia’s resource territories (the Arctic zone, its individual regions, and the Magadan Oblast) allows us to highlight the features of the local level discussed in this article — the production system of an individual enterprise —the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory.

Firstly, the atomic level turns out to be less “regular” in terms of technological wave dynamics, containing a greater number of anomalies and exceptions (for example, a significantly more compressed or extended phase), as well as amplitude “shaking”, than the aggregate level of a resource province, region, or zone. An enterprise always “breathes” more rapidly, nervously, with frequent arrhythmia. Therefore, the rhythm of changing phases and the boundaries between them are more difficult to identify here than for aggregate objects. That is why we are not confident in the correctness of the boundaries we have identified between the industrial and post-industrial long waves of the ASF, within the third wave, between its four phases (for example, the delimitation of the first two frontier phases, interrupted by the war, is controversial; it might have been possible to shorten the duration of the aggressive investment phase to 1966, rather than 1976 — in this case, all subsequent phases of the third and fourth Kondratiev waves would have shifted leftward; perhaps, in that case, the currently too short final twilight phase, having shifted leftward, would have turned out to be longer; the first frontier phase of the post-industrial wave, stretched over 20 years, is not entirely convincing — it would have been possible to identify a transitional moment between the end of the third and the beginning of the fourth Kondratiev wave due to the national economic crisis that lasted for more than 10 years). The overall duration of the industrial wave we identified, 62 years instead of the usual 50 years, is also debatable.

Secondly, at the local level, the connection between the rhythm of the enterprise and the rhythm of the country, which is determined by political events and changes in central government leadership, is much weaker or even absent. The graphs of the ASF’s natural resource use dynamics (Figs. 1–3) do not allow us to see either 1953 or the period of the economic council experiment as separate, demarcated boundaries. However, analogies to national “campaigns”, such as the expansion of corn beyond its natural latitudinal zone, can be seen at the enterprise level in the form of a short “fascination” with mass-produced but low-value products such as seaweed powder and fucus middlings.

Thirdly, at the local level, the role of the enterprise manager as a regulator of the duration and boundaries of individual phases of long waves of technological renewal of the enterprise is more visible. Therefore, in cases where we were uncertain about the clarity of the boundaries and could not see them in the graphs of natural resource use dynamics, we relied on the dates of the directorship of key managers of the factory and adjusted the boundaries of the phases to these milestones.

In general, it can be argued that the emergence of a new economic philosophy is more evident in structures exploiting biological resources than in mineral resource or fuel and energy industries. They are closer to nature and more vividly manifest the values of the new economic era.

Conclusion

The economic history of the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory demonstrates the remarkable flexibility of the enterprise’s production system, which over the course of a century has repeatedly shifted its core specialization to meet the emerging challenges of import substitution. The enterprise was originally created in response to the challenges of import substitution as an iodine factory, then, in response to new challenges, it successively became an agar factory, an experimental factory, a state unitary enterprise, a joint-stock company, and now it is a limited liability company. Clearly, the future history of the factory will be inextricably linked to the country’s need for import substitution of seaweed products. According to the FAO, between 2010 and 2017, agar imports to Russia amounted to 1,136 tons [29, Podkorytova A.V., Roshchina A.N., Burova N.V.].

Russia’s demand for food alginates is also only partially met. The ASF has good potential for future growth based on import substitution. However, the effects of resource depletion could pose a serious threat to the company’s sustainable growth, as demonstrated by the lessons of its development during the third Kondratiev wave. Therefore, the transition to plantation cultivation of certain seaweed types, to aquaculture, seems to be the only option for the ASF.

Within the Kondratiev wave, the first phase of “opening” a new frontier, which initiates the launch of a new cycle, plays a special role in a resource-based enterprise. Its basic feature is a “candle-shaped” increase in the volume of new resource production over a very short period. New harvesting and vertical take-off are the basic features of the frontier phase. Subsequent growth may be just as dynamic, but it is no longer a frontier because the features of novelty have been lost: staples become simply resources.

Our work on the century-long economic history of the Arkhangelsk Seaweed Factory inevitably raises a broader question: what should be the optimal organizational structure of the seaweed business in the White Sea in the future — a single monopoly enterprise or several medium- and large-scale enterprises like the ASF? It is advisable to consider several development scenarios for the entire White Sea basin as a whole: many harvesters — one ASF (the situation of the 1970s and 1980s, the “golden era”); many harvesters — many ASFs; one ASF that is also the main harvester of seaweed raw materials (the current situation). We were unable to answer this question in this article due to a lack of information and knowledge of the situation in our neighboring White Sea region — in the Republic of Karelia and in the Murmansk Oblast. It would be advisable to direct future research efforts towards further exploration of this topic.