Armed violence among the Altai mountains pastoralists of the Xiongnu-Sarmatian age

Автор: Tur S.S., Matrenin S.S., Soenov V.I.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145393

IDR: 145145393 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.4.132-139

Текст обзорной статьи Armed violence among the Altai mountains pastoralists of the Xiongnu-Sarmatian age

During the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD, the Altai Mountains region was under the military and political influence of warlike Central Asian nomadic empires: Xiongnu (2nd century BC to the 1st century AD), Xianbei (2nd–3rd century AD), and Zhouzhan (second half of the 4th to the 5th century AD). The succession of empires had a serious impact on ethno-cultural and socioeconomic processes in the region.

The archaeological sites of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Altai of the Xiongnu-Xianbei-Zhouzhan period (which is also broadly referred to as the Xiongnu-Sarmatian Age) are assigned to the Bulan-Koba Culture. Numerous weapon items found among grave goods, as well as the presence of cenotaphs at the Bulan-Koba

Material and methods

Our sample was composed of 470 skulls from 20 cemeteries of the Bulan-Koba Culture, mainly from Central Altai (Table 1, Fig. 1). In order to analyze the temporal change in the prevalence of trauma, the sample was, when possible, divided into two subsamples: Xiongnu-Early Xianbei (2nd century BC to early 3rd century AD) and Late Xianbei-Zhouzhan (second half of the 3rd to 5th century AD). The sexes and ages of the individuals were determined with standard osteoscopic techniques (Standards…, 1994). The following age cohorts were used: children (younger than 12 years), adolescents (12–16 years), and adults (young – 17– 35 years, mature – 35–50 years, old – more than 50 years).

Traumatic lesions were noted and described using criteria described in the paleopathological literature (Berryman, Haun, 1996; Lovell, 1997; and others). The traumas were assigned to two main groups: antemortem (before death) and perimortem (at or around death). It is not always easy to distinguish between the two, as bone can retain its elastic properties for up to two months after death (Sauer, 1998). In some cases, however, it is clear that the lesion was not compatible with life. Three main types of traumatic lesions were analyzed: sharp-edge incisions (blade or incised wounds, notches), depressed, and penetrating projectile fractures. The absence of trauma was diagnosed only in the individuals with at least 75 % of the skull preserved. But if an individual was represented by a well-preserved left or right half of the skull, this was included in the sample as 0.5 of observation (Walker, 1997: 149). The total sample included 357 observations. The significance of differences in frequency

Table 1 . Cranial samples used for the study of trauma

|

No. |

Cemetery (legend) |

Period |

Male |

Female |

Children |

Adolescents |

Total |

|

|

1 |

Airydash-1 |

( А1 ) |

II |

35 |

32 |

26 |

10 |

103 |

|

2 |

Bely Bom-2 |

( BB2 ) |

II |

10 |

10 |

5 |

2 |

27 |

|

3 |

Biyke |

( Bi ) |

I/II |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

4 |

Boochi |

( Bo ) |

I/II |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

5 |

Bosh-Tuu-1* |

( BT1 ) |

I |

34 |

11 |

2 |

3 |

50 |

|

6 |

Bulan-Koby-4* |

( BK4 ) |

II |

21 |

13 |

14 |

2 |

50 |

|

7 |

Verkh-Elanda-2 |

( VE2 ) |

I/II |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

8 |

Verkh-Uymon* |

( VU ) |

II |

7 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

19 |

|

9 |

Dyalyan |

( Dyal ) |

II |

4 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

|

10 |

Karban-1 |

( Kar1 ) |

I |

7 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

11 |

|

11 |

Kurayka* |

( Kur ) |

II |

9 |

5 |

7 |

1 |

22 |

|

12 |

Kyzyl-Dzhar-1 |

( KD1 ) |

I/II |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

13 |

Saldyar 2 |

( Sal2 ) |

I/II |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

|

14 |

Stepushka-1, -2* |

( St1, 2 ) |

II |

28 |

6 |

11 |

5 |

50 |

|

15 |

Tytkesken 6 |

( Tyt6 ) |

I |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

16 |

Ulita |

( Ul ) |

II |

15 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

29 |

|

17 |

Ust-Balyktyyul |

( UB ) |

II |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

|

18 |

Ust-Edigan* |

( UE ) |

I |

22 |

20 |

16 |

3 |

61 |

|

19 |

Yabogan-3 |

( YabЗ ) |

I/II |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

20 |

Yaloman-2, western group* |

( Yal2W ) |

I |

5 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

13 |

|

Yaloman-2, central group |

( Yal2C ) |

II |

4 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

6 |

|

|

Total |

I-II |

215 |

118 |

102 |

35 |

470 |

||

Notes. Period I: 2nd century BC to early 3rd century AD; period II: second half of the 3rd to 5th century AD; cemeteries, from which postcranial skeleton was also studied, are marked with asterisk.

Table 2. Perimortal cranial traumas in the Bulan-Koba Culture samples, %

|

Cemetery |

Male |

Female |

Children |

Adolescents |

Total |

|

Airydash-1 |

22.6 (31) |

9.1 (22) |

16.7(18) |

0.0 (7) |

15.4 (78) |

|

Bely Bom-2 |

10.0 (10) |

12.5 (8) |

0.0 (4) |

0.0 (2) |

8.3 (24) |

|

Biyke |

0 (1) |

0 (1) |

|||

|

Boochi |

33.3 (3) |

33.3 (3) |

|||

|

Bosh-Tuu-1 |

3.1 (32) |

0.0 (11) |

0.0 (2) |

0.0 (3) |

2.1 (48) |

|

Bulan-Koby-4 |

0.0 (16) |

9.1 (11) |

0.0 (13) |

2.5 (40) |

|

|

Verkh-Elanda-2 |

0 (1) |

0 (1) |

|||

|

Verkh-Uymon |

33.3 (6) |

0.0 (4) |

0.0 (3) |

15.4 (13) |

|

|

Dyalyan |

0.0 (3) |

0 (1) |

0 (1) |

0.0 (5) |

|

|

Karban-1 |

16.7 (6) |

0.0 (3) |

0 (1) |

10.0 (10) |

|

|

Kurayka |

33.3 (6) |

0.0 (5) |

0.0 (8) |

10.5 (19) |

|

|

Kyzyl-Dzhar-1 |

0 (1) |

0 (1) |

|||

|

Saldyar 2 |

0.0 (2) |

0.0 (2) |

0 (1) |

0.0 (5) |

|

|

Stepushka-1, -2 |

23.1 (26) |

0.0 (4) |

33.3 (3) |

21.2 (33) |

|

|

Tytkesken 6 |

0 (1) |

0 (1) |

|||

|

Ulita |

8.3 (12) |

0.0 (7) |

0.0 (2) |

4.8 (21) |

|

|

Ust-Balyktyyul |

0 (1) |

0 (1) |

0.0 (2) |

0.0 (4) |

|

|

Ust-Edigan |

15.4 (13) |

14.3 (14) |

0.0 (7) |

0 (1) |

11.4 (35) |

|

Yabogan-3 |

0.0 (4) |

0 (1) |

0.0 (5) |

||

|

Yaloman-2, western group |

0.0 (3) |

0.0 (2) |

0 (1) |

0.0 (6) |

|

|

Yaloman-2, central group |

0.0 (2) |

0.0 (2) |

0.0 (4) |

||

|

Period I |

7.3 (55) |

6.7 (30) |

0.0 (10) |

0.0 (5) |

6.0 (100) |

|

Period II |

16.8 (113) |

6.3 (63) |

5.8 (52) |

7.7 (13) |

11.2 (241) |

|

Total |

13.3 (180) |

6.4 (94) |

4.7 (64) |

5.3 (19) |

9.5 (357) |

Notes. In parentheses number of observations is given; periods I, II – see notes to Table 1.

Fig. 1. Location of the Bulan-Koba cemeteries. 1–20 – see Table 1.

of cranial trauma was evaluated using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test, with р < 0.05.

Weapon-related lesions of the postcranial skeleton were fixed in the samples from seven cemeteries of the Bulan-Koba Culture as additional markers of armed violence. Archaeological documentation of the burials was employed as well.

Perimortem traumain the Bulan-Koba skeletal samples

The demographic structure of the aggregate sample of the Bulan-Koba Culture is substantially biased: there are twice as many males than females ( р = 0.000), though at the local level such a unbalanced

sexual composition is observed only at Stepushka-1, -2 (4.7 : 1.0), and Bosh-Tuu-1 (3.1 : 1.0), while in other necropolises the male-female ratio is normal. The differences in the ratio are statistically significant between Stepushka-1, -2, and Ust-Edigan ( р = 0.008), Stepushka-1, -2, and Airydash-1 ( р = 0.004), Bosh-Tuu-1 and Ust-Edigan ( р = 0.028), Bosh-Tuu-1 and Airydash-1 ( р = 0.017). Graves of children younger than 1.5 years are almost not found in the Bulan-Koba cemeteries; most likely they were buried separately. At Bosh-Tuu-1, older children were likely underrepresented as well.

Perimortem cranial trauma. In the Bulan-Koba aggregate sample (across all age groups), the prevalence of perimortem cranial trauma is 9.5 % (Table 2). These injuries are found at the highest frequency at Stepushka-1, -2, Airydash-1, and Verkh-Uymon-1, and least frequently at Bosh-Tuu-1 and Bulan-Koby-4. The inter-site differences are significant between the following samples: Stepushka-1, -2, and Bosh-Tuu-1 ( р = 0.007), Stepushka-1, -2, and Bulan-Koby-4 ( p = 0.020), Airydash-1 and Bosh-Tuu-1 ( р = 0.017). The prevalence of cranial trauma is twice as high in males as in females (13.3 vs. 6.4 % , р = 0.103).

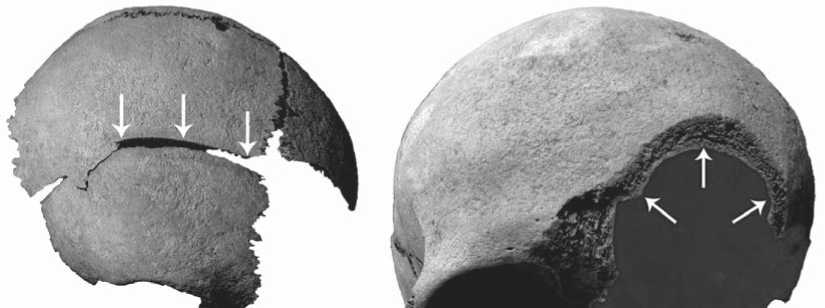

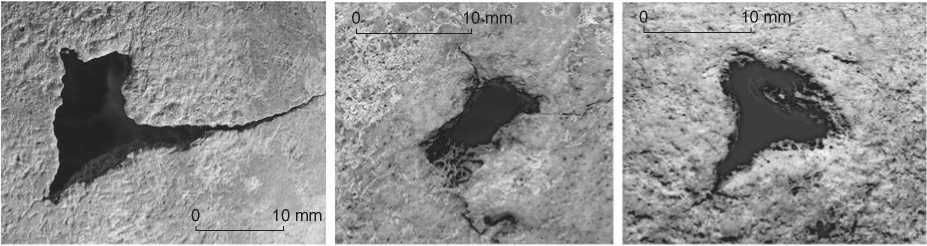

In total, on 34 skulls (24 male, 5 female, 1 adolescent, and 4 children of 2.5–5.5 years of age), we detected 43 cases of trauma without manifestations of healing. These include: 18 blade and 5 incised wounds, 17 penetrating projectile, and 3 depressed fractures. Obviously, deep blade wounds (Fig. 2) from a strong blow with a sword were the immediate cause of death. Most of the penetrating projectile fractures were small in size and were probably caused by the arrowhead, whose cross-section is clearly reflected by the shape of the wound in some cases (Fig. 3). Larger fractures ( BB2/2–9 , St1/6 , St2/39 , UE/28 ) could have been caused by spears, daggers, or chisels. Surface incisions ( St1/1 ) and small depressed fractures ( A1/168–1 , St1/15–1 ) likely originated in warfare as well. In one of these cases ( А1/168 ), a small depressed fracture was combined with a mortal blade wound to the skull. In another individual ( St1/1 ), a surface incised wound of the cranial vault was accompanied by a perimortem lesion to the upper epiphysis of the left tibia—an arrowhead got stuck in that bone. In six male skulls, from 2 to 4 unhealed wounds on each were detected. These were caused by weapons of the same (e.g. sword) or different types

АB

Fig. 2. Examples of deep blade wounds to the skull from Airydash-1.

А – right parietal bone of a child, 5–6 years old (A1/97–2) ; B – left side of the frontal bone of a young female (А1/175) .

А BC

Fig. 3. Examples of penetrating projectile fractures of skulls by arrowheads in Airydash-1.

A – posterior part of the left parietal bone of a young female (А1/55) ; B – sagittal suture near lambda of a young male ( А1 / 126 ); C – posterior part of the left parietal bone of a young male (A1/166) .

(e.g. combinations of an incised/blade injury and a depressed fracture, or of a blade wound and a depressed fracture).

Decapitation, severed limbs, scalping, arrowheads stuck in postcranial bones. Skulls were absent in three undisturbed male burials at Airydash-1 and Stepushka-1 ( А1/30, 59, St1/5 ), which can probably be interpreted as the result of decapitation. At Stepushka-1, in two male skeletons ( St1/7, 15–1 ), hand and forearm bones were missing, probably cut off. In another burial ( St1/1 ), bones of the right hand were found to the side of the skeleton, in the anatomically right articulation. From these three individuals who had lost their right hands, two had been injured by arrows as well. Arrowheads had got stuck in the orbit of the St1/15–1 individual, and in the proximal epiphysis of the left tibia of the St1/1 individual. Arrowheads stuck in postcranial bones were also found in two more male burials: from Stepushka-2 ( St2/27 – in the sternum) and Karban-1 ( Ka1/11 – between two thoracic vertebrae). Thus, all cases of probable decapitation and severed limbs, as well as arrowheads in postcranial bones, were observed in the burial grounds displaying increased prevalence of mortal cranial trauma.

Several cases can be interpreted as the results of scalping or other manipulations with the head of a victim. These include small parallel incisions on the frontal bone of the male skull from Boochi ( Bo/15–1 ), similar lesions on the temporal squama of the female skull from Bely Bom-2 (BB2/10–1) , and cutting of the cortical bone layer of the frontal and adjacent parts of the temporal bones on the male skull from Verkh-Uymon (VU/20) , in which four blade wounds were found as well.

Beginning in the second half of the 3rd century AD, there was a trend to an increase in the rate of combat violence: the frequency of perimortem cranial trauma in males increased from 7.3 to 16.8 % ( p = 0.101); and mortal trauma in children and adolescents, as well as signs of ritual manipulations with dead bodies, start to be observed.

Discussion

The increased male-to-female ratio observed in the aggregate and some local samples of the Bulan-Koba Culture is also typical of the demographic structure of a number of other cemeteries of Eurasian nomadic pastoralists of the Early Iron Age (Alekseev, Gokhman, 1970: 247–248; Borodovsky, Voronin, Shpakova, 1996; Mednikova, 2000: 72; Razhev, 2009: 49; Balabanova, 2015: 117). This fact can be explained by the traditional favor towards boys rather than girls in families, and by migration, warfare, or different burial rites for different social groups. In burials of the Pazyryk Culture of the Scythian period, which immediately preceded the Bulan-Koba Culture in the Altai Mountains, that ratio was equal

(Tur, 2003: 137; Chikisheva, 2012: 138; Borodovsky, Tur, 2015: 132).

But the higher rate of trauma in males seems to be a universal trend in various regions in different periods, including the Bulan-Koba (Knüsel, Smith, 2014). The frequency observed in the studied male sample (13.3 %) points towards an increased “militarization” of the Altai Mountains population of the Xiongnu-Sarmatian period. Weapons are found in all male, and even in some child burials. The arsenal of the Bulak-Koba people included composite bows, with a variety of arrow types, spears, swords, daggers, combat knives, and armor. The qualitative and quantitative differentiation of weapon inventory across male burials is probably related to their military hierarchy (Gorbunov, 2006: 89–90).

Mortal wounds are found in female skeletons as well (6.4 % ). Ethnographical evidence regarding the participation of females in raids is quite known (Adams, 1983: 200–202). Antique authors tell about warlike amazons among the Scythians and Sarmatians (Kotina, 2012: 7–9). In the archaeological context, weapons in female burials, as well as combat traumas in female skeletons, may be suggestive of martial activity by women (Guliaev, 2003). Some military items are found in female burials of the Bulan-Koba sites in Central Altai (e.g., an arrowhead – BK4/5–11 , BB2/10–1 , or a couple of armor plates – Yal2З/57 , 61 ), but these finds can be interpreted from different points of view (Soenov, Konstantinov, Trifanova, 2015a: 21–22). There is no correlation between the above-mentioned burial items and combat traumas on female skulls. However, it cannot be excluded that in some instances females had to take up arms to protect themselves; on the other hand, there is not enough evidence to hypothesize their participation in offensive warfare*.

The prevalence of perimortem cranial traumas varies among the local samples of the Bulan-Koba Culture. In the second half of the 3rd to the 5th century AD sample, this frequency doubles in males. This temporal difference does not reach the level of significance, but is accompanied by an increased frequency of combat wounds to the postcranial skeleton. Taken together, these evidences prove the reality of increased martial activity during the Late Xianbei-Zhouzhan period. In addition, lethal injuries to the skulls of children and adolescents, as well as signs of ritual manipulations with bodies of killed males, can be observed in the sample of this period, unlike the previous Xiongnu-Early Xianbei age.

Our analysis of ethnographic and historical sources has shown that the system of social control and coercion in traditional societies was based on the principles of blood feud and group responsibility. But the exact form of the military conflict largely depended on the “social distance” between conflicting groups, and was determined by the natures of their relationships. Mechanisms of peaceful resolution of conflicts were typically developed in culturally similar groups integrated by common origin, kinship or marital links, trade or exchange relations. Such mechanisms could have helped to restrict the frequency, duration, scale, and severity of military conflicts, and to minimize human and material losses. In contrast, the absence of social relationships between conflicting parties created opportunities for inhuman treatment of enemies, including killing civilians, capture of young women, ritual manipulations with victims’ bodies, and destruction of property and food supplies (Pershits, 1994: 166–169; Solometo, 2006: 27–37). Judging from this, it can be suggested that during the Xiongnu-Early Xianbei period (2nd century BC to early 3rd century AD), interpersonal and local intergroup conflicts were the main causes of lethal injuries in the Bulan-Koba population. Military clashes in nomadic societies were typically sparked by murders, causing injuries (even unintentional ones), sex crimes, violation of matrimonial rules, or robberies (Pershits, 1994: 166–169). Social tension commonly increased in the situations of high population density, lack or instability of natural resources, or intense immigration (Ember С.R., Ember M., 1992).

The influx of immigrants, which is detected by means of archaeological data (Tishkin, 2007: 177–179; Seregin, Matrenin, 2016: 144–147; 158–163), might have been one of the factors in the increased prevalence of mortal trauma in the Bulan-Koba area during the Xiongnu-Early Xianbei period. At the end of the period from the 3rd to 5th century AD, there was an increase in martial activity in the region, most probably related to the change of political situation in Central Asia—the collapse of the Xianbei Empire and escalation of an internecine struggle for power. This was accompanied by the emergence of new political alliances of nomads, and widening of the circle of participants in military conflicts (Materialy…, 1989: 5–9, 12, 20–21, 30–31; Vorobyev, 1994: 218–221, 298).

The observed differences in the distribution of combat wounds in the samples from the Late Xianbei period from Airydash-1 and Stepushka-1, -2, in the context of their demographic structure and archaeological data, suggest two possible scenarios. In the first case, the male-to-female ratio is close to normal; juvenile and young adult individuals are prevalent among females; lethal injuries (mostly deep blade wounds) are found not only in males, but also in females and children less than 6 years of age. Some of the males were decapitated. Three out of 16 cenotaphs contained items of female inventory (spindle whorl, adornments), while others did not contain any goods (unpublished data by A.S. Surazakov). Apparently, this group was attacked by members of tribes extraneous to them in an ethnic/cultural sense; and during this assault, some of the young females were killed, and some were captured. The pattern of prevalence of mortal trauma is fairly similar in Airydash-1 in Altai, and Aimyrlyg-31 (Murphy, 2003: 54–95) and Kokel (Weinstein, 1970: 17–18, 36; Dyakonova, 1970: 93–187) in Tuva.

The sample from Stepushka-1, -2 is characterized by a substantial prevalence of male burials, and an almost complete absence of young females. Lethal traumas are found only in males and in one adolescent buried with “adult” set of weapons. Cases of decapitation and severed right hands are observed, while blade wounds to the skull are absent. There are many cenotaphs, some with weapons, that might be viewed as symbolic burials of warriors who died far from home (Tishkin, Matrenin, Schmidt, 2013; Soenov, Konstantinov, Trifanova, 2015b). Possibly, males of this group were engaged in longdistance raids, having left young women at the risk of being captured.

It is of note, however, that mass graves that can be interpreted as a result of warfare aimed at the extermination of a particular group are not found in the Altai Mountains in the Xiongnu-Sarmatian period.

Conclusions

The results of the present study have shown that the emergence and succession of ruling empires in Central Asia (Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Zhouzhan) were affecting the rate of armed violence in the Altai Mountains, which region was in the sphere of the military and political influence of those empires. During the Xiongnu-Early Xianbei period (200 BC to early 200 AD), perimortem trauma among the Altai Mountains pastoralists was related mainly to interpersonal and local intergroup violence. Between the late 200s AD and 500 AD, following the disintegration of the Xianbei Empire and the rise of intergroup clashes, the Bulan-Koba people also became involved in military conflicts with culturally/ethnically alien tribes.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, Project No. 16-06-00254 (S.S. Tur and S.S Matrenin), and the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, Public Contract Project No. 33.1971.2017/4.6 (V.I. Soenov). The authors express their gratitude to A.S. Surazakov for sharing his unpublished archaeological data on the cemetery of Airydash-1.