Burial of a Hunnic period noblewoman at Karakabak, Mangystau, Kazakhstan

Автор: Astafyev A.E., Bogdanov E.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146410

IDR: 145146410 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2021.49.4.057-068

Текст статьи Burial of a Hunnic period noblewoman at Karakabak, Mangystau, Kazakhstan

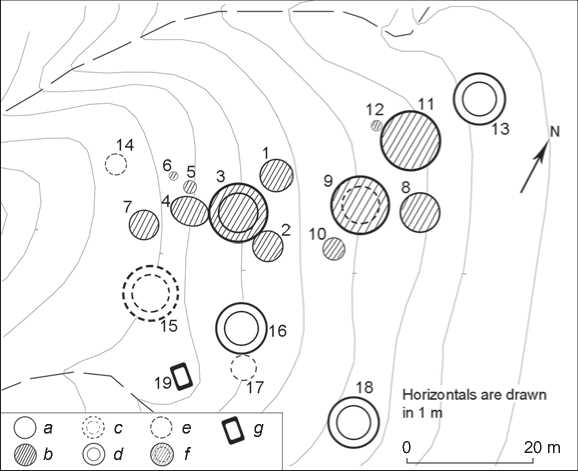

In 2019, the Russian-Kazakh expedition excavated a burial ground of the Hunnic period near the settlement of Karakabak in Tupkaragansky District of the Mangystau Region, the Republic of Kazakhstan (Fig. 1). Twelve structures were explored (Fig. 2), of which seven contained burials. The results of studying burials 1–3 and 10 have been partially described (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2020a, b). The variety of the evidence, its ambiguity, and most importantly its uniqueness for the entire Aral-Caspian region have fostered gradual publication of the excavation in the form of a series of articles. This publication describes burial 11 at the Karakabak-10 cemetery located on the western side of the canyon of the same name.

Fig. 1 . Location of the Karakabak-10 cemetery.

Fig. 2 . Topographic plan of the cemetery.

a – embankment, burial mound; b – objects explored; c – stone placement (?) with depression in the center; d – ring-shaped stone placement; e – stone placement of amorphous outline; f – burial mounds with depression in the center; g – burial structure from the ethnographic time.

Burial complex and ritual

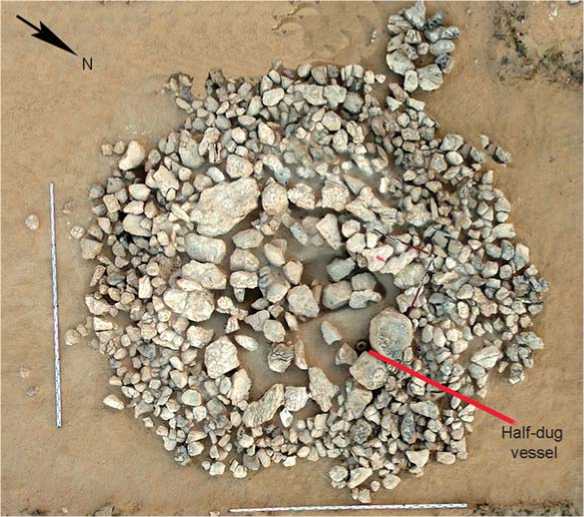

Burial 11 was located on a slope with height difference reaching 0.5 m over a length of 6.5 m. It appeared as a mound-like stone placement 6 m in diameter (Fig. 3). Pieces of limestone and flint lay on the ancient surface in one or two layers. The main mass of stone was concentrated in the southern sector and consisted of rocks removed in the course of grave robbing. In the center of the structure was clearly visible the circular placement of large blocks in one row, 4.2 m in diameter. A hand-molded vessel with broken neck, half-dug into the ground, was inside them, in the northern sector, near one of the blocks. The slightly concave bottom of the vessel was broken when the vessel was already in the ground. An empty hole, 0.25 m in diameter and 0.15 m in depth, was located 0.3 m to the east of it.

After removing the stone ring, the boundaries of the grave pit, partly destroyed by the robbers’ pit, were identified. Initially, the grave pit had an elongated shape with an expansion in the southern sector and was oriented along the NNE-SSW line. The probable overall size of the pit was 1.8 × 0.95 m, with an average depth of 1.9 m relative to the level of the ancient surface. The northwestern sector was destroyed by the 1.6 × 0.9 cm shaft, which cut through the filling of the grave pit and

Fig. 3 . Ground structure above burial 11.

roof of the burial chamber, which had a niche. The remains of stone placement in the burial chamber were found near the western wall of the burial pit, at the level of the bottom (Fig. 4). Slabs installed vertically (at an angle) were set in three rows. The inner and second row stood at the bottom of the burial chamber; the third row was installed on the bottom of the grave pit, which marked exactly a step 16–27 cm high. The height of the burial chamber vault can be reconstructed from the height of the burial, which was 0.6 m. Judging by the consistency of soil and typical features of the collapsed vault, the burial chamber was not filled with soil after the burial. Ribs, vertebrae, and bone fragments of human arms and hands were found in the robbers’ pit close to the bottom of the grave pit. The gold casing of a wooden belt buckle and “spindle whorl” made of the wall of a hand-molded vessel were also found there.

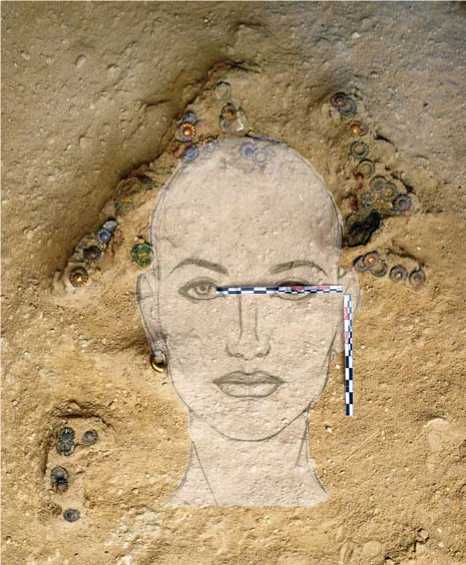

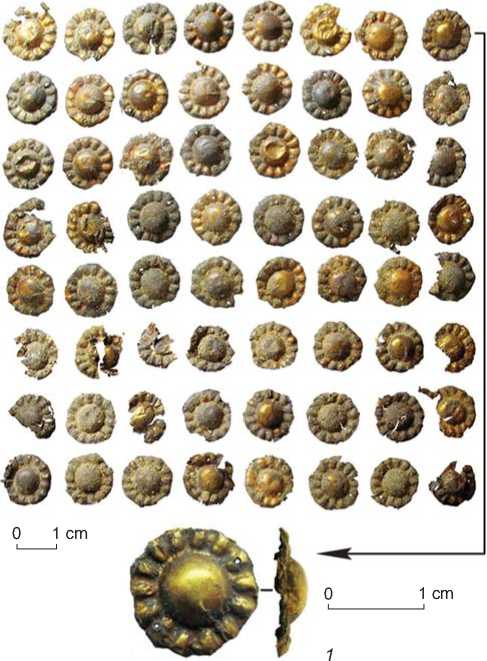

On the bottom of the burial chamber (2.6 × 0.7 to 1.0 m), the remains of a disturbed human skeleton were discovered. The bones of the legs and feet, right hand, as well as left forearm and hand, survived in anatomical order. The deceased girl was buried in an extended supine position (arms stretched along the body; legs lying freely), with her head to the north (Fig. 5). In the area of the head, remains of the headdress were found in situ (Fig. 5, 6) in the form of local accumulations of forty small stamped plaques (Fig. 7, 1 ) and two mask-plaques with fragments of reddish silk fabric (Fig. 7, 2 , 6–9 ). A gold earring (Fig. 7, 5 ) and mask-plaque (Fig. 7, 8 ) were found in disturbed state in the head area, but 10–20 cm above the bottom of the grave. The location of the non-preserved skull was marked by a gold earring (see Fig. 6; 7, 4 ) in situ (similar to the earring

Fig. 4 . View of the grave pit and partition (filling) made of chalk slabs.

Fig. 5 . Skeletal remains and grave goods on the bottom of the grave pit.

Fig. 6 . Location of gold plaques in situ in the area of the head of the buried female.

1 cm

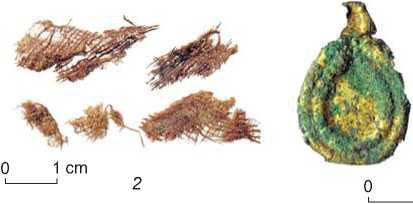

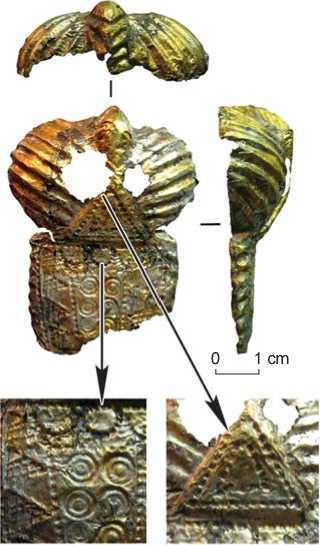

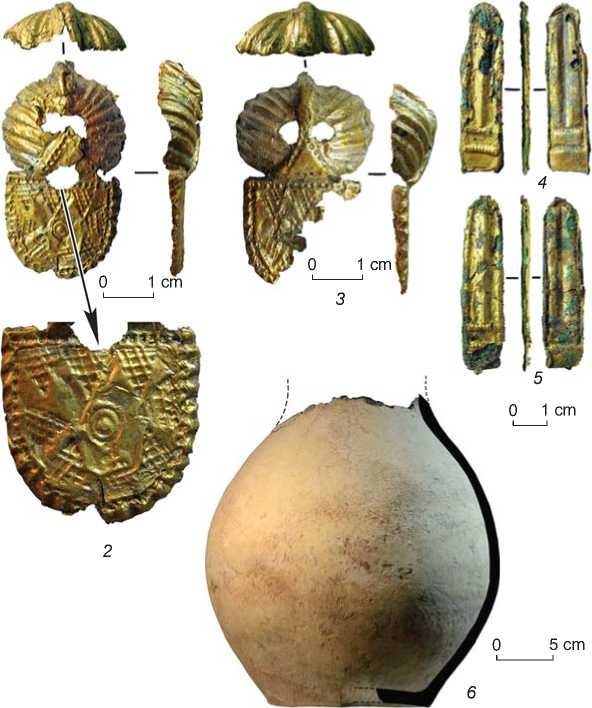

Fig. 7 . Elements of the headdress.

-

1 – gold sewn-on plaques; 2 – fragments of cloth; 3 – laminar pendant; 4 , 5 – earrings; 6 , 7 — casings of mask-plaques;

-

8 , 9 – base of the ornaments; 10 – forehead plaque.

1 , 3–7 , 10 – gold; 8 , 9 – wood.

Fig. 8 . Reconstruction of the headdress.

found in the robbers’ pit) and two mask-plaques in the area of the temporal bones (see Fig. 6; 7, 6–9 ). Small plaques in situ lay in a semicircle within the area of the cranial vault (see Fig. 6). Judging by their location, they were originally sewn onto thin fabric in two rows, with a probable interval of 12–13 mm in a checkerboard pattern. The plaques could have been located in this way only if the thin fabric slipped off the head. Originally, they must have been sewn along the edge. A drop-shaped pendant plate was found below the right mask-plaque (see Fig. 6; 7, 3 ); it was displaced. All the evidence has made it possible to reconstruct the headdress (Fig. 8).

Elements of two shoe straps (Fig. 9) have survived in the area of the ankles. The gold embossed casing of a wooden buckle (small fragments of the base with relief have survived) (Fig. 10, 2 , 3 ) was at one end of each strap; a laminar tip was at the other end (Fig. 10, 4 , 5 ). The buckles faced in opposite directions from each other. A fragment of a wicker item made of plant fibers has survived (Fig. 11, 5 ) between the shin bones, under half of a bronze mirror (Fig. 11, 3 ). A tip of a dart (or double-edged knife?) (Fig. 11, 4 ) and “spindle whorl” made of the wall of a vessel manufactured on a potter’s wheel (Fig. 11, 2 ) lay nearby, under a scattering of beads (Fig. 11, 7–10 ).

The data obtained during the excavations suggest that the burial complex was disturbed with the purpose of removing the head of the buried girl, since the rest of the bones have survived in some way or other ( in situ or in the robbers’ pit), and the gold items were left behind.

Description of the grave goods

The round plaques (64 spec.) were made of gold foil by embossing on a base (see Fig. 7, 1 ). Their diameter is 12–14 mm. The relief decoration represents a raised hemisphere framed by convex oval-petals around the perimeter.

The small mask-plaques (2 spec.) have the shape of oval medallions. Their carved wooden bases were lined with thin gold foil with the embossed images of a human face framed by ascending “rays” (see

Fig. 9 . Bones of legs and feet with remains of shoe straps and accompanying goods.

5 cm

0 1 cm

0 1 cm

0 1 cm

Fig. 10 . Finds from the burial.

1 – belt buckle casing; 2 , 3 – shoe buckle casings; 4 , 5 – tips of shoe straps; 6 – vessel. 1–3 – gold; 4 , 5 – copper and gold foil; 6 – clay.

1 cm

1 cm 10

Fig. 11 . Finds from the burial.

1 – “spindle whorl” from the wall of a hand-molded vessel; 2 – “spindle whorl” from the wall of a vessel made on a potter’s wheel; 3 – mirror fragment; 4 – knife(?) / dart tip(?); 5 – fragment of a wicker item; 6–10 – beads.

-

1 , 2 – clay; 3 – bronze; 4 – iron; 5 – plant fibers; 6 – stone; 7–10 – glass.

Fig. 7, 6–9 ). There are two types of mask-plaques “with closed eyes”: conventionally, “male” and “female” types (on the headdress, they were located on the left and right sides, respectively). The “male” face of Caucasoid outline was carved in half-relief on an inverted teardrop shape. The eyebrows are slightly curved and sloping; the base of the closed upper eyelid is straight and oblique; the nose is straight; the mouth is small with an enlarged lower lip. There are four holes along the edges of the medallion (top, bottom, and sides). The size of the foil casing is 34 × 25 × 7 mm. The “feminine” face in a heart-shaped outline has obvious Mongoloid features. The eyebrows are arched; the base of the closed upper eyelid is curved and almost horizontal; the nose is long, with wide nostrils; the mouth is elongated, with large lips. One fifth of the medallion has been lost. The size of the foil casing is 42 × 23 × 9 mm.

The large mask-plaque is a copper disc 58 mm in diameter, lined with gold foil with punch-matrix embossing (see Fig. 7, 8 ). A face of the Mongoloid type with slanting eyes, wide protruding cheekbones, large nose, and narrow elongated lips was depicted in relief. The chin is bifurcated. The mouth is half-open, with four strongly protruding canines. The mask-plaque is outlined with embossing in the form of a strongly entwined cord.

A laminar drop-shaped pendant-imitation was made by punch-matrix stamping from a copper sheet with a slightly bent edge (see Fig. 7, 3 ). The item has an unpierced eyelet. Its size is 25 × 16 mm. The outer surface of the pendant is gilded. The relief band with cord decoration imitates a frame with stone insert.

The solid gold ring-shaped earrings (2 spec.) measure 18 × 16 and 17 × 15 mm. The ends of the rods, closed into a ring with thickening in the middle part in the form of a ring-shaped ridge 6 mm in diameter, were strongly narrowed (see Fig. 7, 4 , 5 ).

Fragments of thin reddish fabric remaining from the headdress (see Fig. 7, 2 ) make it possible to suggest the method of its manufacturing, namely, the principle of plain weave, where the warp thread is much thinner than the weft thread.

Foil casing on a wooden base forms an imitation of a belt buckle with oval frame, prong, and flat quadrangular shield (see Fig. 10, 1). Its overall size is 61 × 45 × 18 mm. The frame with fixed prong is decorated with relief embossing depicting a bird of prey with half-lowered, spread wings and spread tail. The curved end of the prong constitutes the “bird’s head”. Its other end (the “bird’s tail”) is decorated in the technique of point embossing in the form of two triangles inscribed one into the other. The field of the shield is decorated with triangles of false granulation and figures of concentric circles. The edges of the shield are beveled and decorated with slanting notches. Foil on both sides of the prong is damaged.

Foil casing on wooden bases (2 spec.) form an imitation of shoe buckles (see Fig. 10, 2 , 3 ). These items are similar in type and ornamentation to the belt buckle, only with smaller size: 42/44 × 25/27 × 9 mm. The foil is of poor degree of preservation; there are losses.

The tips of shoe straps (2 spec.) are elongated copper plates with one slightly narrowed and rounded end, lined with gold foil on both sides (see Fig. 10, 4 , 5 ). Their size is 43 × 13 mm. A wide band runs along the center of the plates along the entire length; it is bounded at the straight end by two transverse corrugated thin bands. The fastening elements are absent.

The half of the bronze mirror has a ridge along the edge and flattened protrusion-loop in the center (see Fig. 11, 3 ). The diameter is 82 mm. The mirror is decorated with relief ornamentation in the form of a ring divided into many sectors by radial rays.

A dart tip (or double-edged knife?) has a short, diamond-shaped, double-sided blade (54 × 28 mm) and long, tapering tang (70 × 13 mm). Remains of decay from the wooden handle (see Fig. 11, 4 ) have survived on the tang with overlap on the blade.

One of two bagel-shaped ceramic “spindle whorls” (2 spec.) was made from the wall of a hand-molded vessel (see Fig. 11, 1 ). Its diameter is 46 mm; its thickness is 13 mm; the diameter of the hole is 8 mm. The other “spindle whorl” was made from the wall of a gray clay vessel made on a potter’s wheel (see Fig. 11, 2 ). Its diameter is 39 mm; its thickness is 8 mm; the diameter of the hole is 7 mm.

There are several varieties of highly patinated glass beads and tubular beads: cuboid with convex and concave end faces, 9 × 8 × 8 mm (see Fig. 11, 7 ); drop-shaped with longitudinal hole, 11 mm long and 8 mm in diameter (see Fig. 11, 8 ); round-flattened with a diameter of 3.0–4.5 mm (see Fig. 11, 10 ). One tubular bead is spiral, 6 mm long and 4 mm in diameter (see Fig. 11, 9 ); the rest have the shape of undivided columns (intact and fragments); their length is 5– 16 mm and diameter is 3 mm.

A spherical bead made of a red translucent stone (carnelian?) is 17 mm in diameter (see Fig. 11, 6 ). One third has been chipped off.

Interpretation of the evidence

Material evidence from the Karakabak burials does not contradict the opinion that most of the Late Sarmatian specific aspects of funeral rituals survived in the Hunnic period over the vast territory of the Eurasian steppes, including the Aral-Caspian region (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2020a: 84). These include the presence of ring-shaped stone placement at the burial ground, burial under an individual embankment in a grave with a niche in the western wall, setting of stone slabs, burial of a human in an extended supine position with the head to the north, presence of “spindle whorls” made of pottery walls, and fragment of a mirror with radial-ray decoration among the female accessories. Absence of funeral food in the grave and a ceramic vessel buried near the ground structure (moreover, to the north of it!) (see Fig. 10, 6 ), with a pit nearby, can be viewed as markers of the Hunnic period. This aspect of the burial rite, associated with the “offering” (of liquid), is a phenomenon of the same order as rituals observed in stone structures of Altynkazgan (see (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2018a: 355–361)). There are also striking similarities not only in the shapes of the vessels, but also in many types of grave goods. For example, the large mask-plaque and elements of shoe straps (shapes of buckles and prongs) found in the burial under consideration have parallels in “hoard” No. 3 from enclosure No. 158 (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2018b: Fig. 6, 10–14 ). Analysis of these items confirms our earlier assumption that personal ornaments for the nomadic elite could have been made in Karakabak by artisan-jewelers (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2020a: 87) who worked equally well both with casting and chasing. In this sense, burial 11 does not stand out from the general picture obtained during the excavations at the Karakabak-10 cemetery; namely, it can be dated from the second half of the 5th to early 6th century and it belongs to the Alanian-Sarmatian nomadic elite closely associated with the Karakabak artisanal and trading center. However, there is one very important point: unlike other burials examined at the cemetery, we do not see the influence of the “Pontic fashion” in the outfit of the buried girl. Moreover, all its elements are imitations of real things*. These were commissioned for a specific event (burial of a deceased person).

The first point that may be observed is the absence of clear chronological indicators. We have already written about Karakabak golden ring-shaped earrings and their parallels (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2020b: 188). Disc-shaped “spindle whorls” made of the walls of ceramic vessels, and mirrors with radialray ornamentation and a protrusion-loop in the center appear over the same vast area (types IX and X according to the classification by A.M. Khazanov (1963: 67–69, Fig. 4) or “of the Berezovka–Anke-2 type” in the terminology of A.V. Mastykova (2009: Fig. 91, 92)). A wide range of parallels to the laminar pendant with imitation of a frame only emphasizes the popularity of such ornaments both in the nomadic environment and among the sedentary population of the Hunnic and post-Hunnic times. Belt tips in the form of an elongated plate with ribbed bands and casing of gold foil (and without it) appear among the evidence from sites in Hungary, the North Caucasus, Crimea, the Volga region, and the Urals (Werner, 1956: Taf. 64, 11–14; Zasetskaya, 1994: Pl. 1, 9; 17, 16; 22, 1; 26, 1; Gabuev, 2014: Fig. 66, 6; Kurgan s “usami”…, 1999: Fig. 23; Bisembaev, 2020: Fig. 1, 15). However, belt and shoe buckles from Karakabak burial 11 do not typologically fit the available classifications of Hunnic antiquities (V.B. Kovalevskaya (1979: 15– 48), A.K. Ambroz (1989: 63–81), I.P. Zasetskaya (1994: 77–99), A.V. Komar (2000: 23–32), etc.). It is necessary to keep in mind that these are imitations (gold casings on wooden bases) that have never occurred before. Techniques for decorating shields and the ornamentation of concentric circles, triangles and pseudo-granulation are typical of the Hunnic and post-Hunnic periods. These ornamental motifs appear on the casing of a sword sheath from the Volnikovsky “hoard” (Volnikovskiy “klad”…, 2014: 88–90). Moreover, the composition on the shield of the Karakabak belt plate repeats the layout of inlaid elements on the shield of the sword belt buckle (Ibid.: 36–37), only made less carefully. One gets the impression that the artisan who made the Karakabak artifacts saw some original samples and imitated them using the methods he knew. The parallel of the Karakabak samples with belt buckles from burials near the village of Shipovo (the Volga region) (Zasetskaya, 1994: 90–91, pl. 40, 3; 42, 6; fig. 19, c), catacomb 10 near the Lermontov Rock (Runich, 1976: Fig. 3, 9), and catacomb 40 in Mokraya Balka (Afanasyev, Runich, 2001: Fig. 58, 7) (North Caucasus) is very interesting, especially if we take into account the discovery of shoe buckles of the “Shipovo type” in burial 2 of Karakabak-10 (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2020a: Fig. 4, 3). The most interesting detail is the presence of grooved band-notches on the frames, extremely reminiscent of the stylized decoration of Karakabak buckles in the form of bird wings. Such frames have been found only among the evidence of the sites from the Shipovo horizon (Mastykova, 2009: 60–61) or group C5 (Komar, 2000: 35–36). This brings us to a number of questions. The most important question is what is their derivative in this case? Do they derive from the Mangyshlak finds, which seems to be logical given the location of the region far from the main production centers and routes of movement of the Hunnic hordes, or vice versa?

Analysis of the burial outfit from Karakabak burial 11 may provide some clarity. According to Mastykova, “the prototype of a prestigious headdress with gold appliqués should be sought for in the antiquities of the Hellenized population of the Late Antique centers in the Northern Black Sea region” (2014: 137). Since the principle of decorating clothes with sewn-on plaques was not widespread in Europe in the Hunnic period, it is not surprising that headdresses decorated in this manner were absent in European reconstructions of nomadic outfits (Ibid.: Fig. 119– 125). Meanwhile, round plaques with a hemisphere in their center widely appear in the evidence of the 4th–6th centuries from the Bosporus (Aibabin, Khairedinova, 1997: Fig. 13, 1 ; Taina zolotoy maski…, 2009: 39, cat. No. 25, 26; Ermolin, 2009: Fig. 3, 8 ) and North Caucasus (Gabuev, 2005: 40, cat. No. 82) to the Southern Urals and Cis-Urals (Botalov, 2013: 212; Bisembaev, 2020: Fig. 13). However, first of all, with the exception of the headdress of the woman from burial mound 22 at the Soleny Dol cemetery (Botalov, 2013: 232), they adorned the collar of the dress and/or sleeves. Second of all, the edges of the plaques were decorated with pseudo-granulation— dots and not “petals”, as is the case with the Karakabak artifacts. The latter consideration makes it possible to speak about the “solar nature” of the representation and see parallels in the Sarmatian and even Scythian evidence. We will discuss this further later. The most surprising detail in the headdress of the Karakabak girl is the headband with mask-plaques (see Fig. 8). Here, we face a paradoxical situation. Dozens of pages in monographs and articles by various scholars analyze buckles (prongs, frames), fibulae, and other everyday items, with fierce debates about their typology and chronology. Yet, the phenomenon of the emergence of “Hunnic” mask-plaques in the steppe was mentioned only in the context of decoration of the horse harness, although this assumption is speculative owing to plundering and heterogeneity of the complexes.

Anthropomorphic images embossed on gold plates (placed on a copper base plate) are chronologically indicative precisely of the Hunnic antiquities (Ancient Intercisa, Hungary) (Ambroz, 1989: Fig. 30, 12 ). Surprisingly, their main location is the Volga region (burial mounds 17 and 18 near the town of Pokrovsk, the destroyed burial in Pokrovsk-Voskhod, burial mound 4 near the village of Vladimirskoye), the Northern Black Sea region (burial VII near Novogrigorievka), and North Caucasus (Upper Rutkha) (Bona, 1991: 28, fig. 9), and the burial on the territory of Ufa (Tukaev street) (Ambroz, 1989: Fig. 34, 5 ) with the extreme eastern point at Mangyshlak (Altynkazgan, Karakabak). Taking into account the conventionality in drawing the crumpled gold foil of casings by contemporary artists, we can only conclude that there is a variability of images. The similarity with the Mangyshlak masks can be observed only in design (“cord” ornamentation along the edge) and technology (copper disc on rivets at the base). O. Maenchen-Helfen assumed the Iranian origin of some Hunnic masks with a beard, based on the observation that according to Ammianus Marcellinus (XXXI. 2), large beards are not typical for the Huns; they are common among the Scythians and Sarmatians (1973: 281–284). According to A.K. Ambroz, “the emergence of masks on the harness among the nomads can be associated with the influence of Rome or Iran” (1989: 73). Citing the opinion of C. von Carnap-Bornheim that the Volga masks derived from the Late Roman and Germanic models, M.M. Kazansky quite rightly pointed to the inexplicable remoteness of the majority of the finds from the borders of the Roman-German world (2020: 100). What can be found in the West?

-

1. A group of brooches with glass, inserted masks from the Sarmatian complexes of the 3rd–4th centuries in Pannonia (Grumeza, 2014). The artifacts made in this specific tradition were discovered two centuries later in the North Caucasus (Kharbas-1, Kamunty, and two accidental finds) (Sadykov, Kurganov, 2016: Fig. 18, p. 219).

-

2. Small-sized cast masks on gold ornaments from the time of the Great Migration from Germany, Italy, and Scandinavia, made in the Roman technique of jewelry art (see (Balint, 2016: Fig. 1, 3, 7, 34)).

-

3. Various kinds of images of divine faces, portraits of Roman emperors on gold sewn-on plaques, coins, phalerae, etc., going back to the traditions of Antiquity and made in Roman and Byzantine production centers.

A huge number of such items circulated among the elite of the Barbarians, where each ruler could feel his involvement with the supreme deities. A good example of this is the bronze plate that adorned a wooden bucket from Giberville (France), which was dated to the 4th century. “Represented from left to right: the profile of a Roman emperor (Valentinian?)—an imitation of a coin, followed by a hunting scene, which ends with the figure of the standing Emperor striking the enemy— probably also an imitation of a coin, followed by the frontal image of a face—an exact parallel to the masks of the Hunnic period” (Ishtvanovich, Kulchar, 1998: Fig. 5). The Altynkazgan phalera and headdress from Karakabak burial 11 is even closer to the Antique (Scythian) models than to the Late Roman models in terms of its pictorial features. An example is gold sewn-on plaques from the Deev Kurgan (Northern Black Sea region) (Alekseev, 2012: 238–239) or various images of gorgoneions (including those with fangs) from Scythian burial mounds (Rusyaeva, 2002: Fig. 1, 4; 2). Especially indicative are images of gorgons from Vani (Georgia), which are deprived of decorative “effects”, broad-faced, with stylized hair, open mouth, and gathered brows conveying negative emotions (Avaliani, 2012: Ill. 1). In terms of their pictorial canon, they use the same visual language as masks from the Volga region and Northern Black Sea region.

It seems that the reason for local crude production and popularity of masks in the eastern periphery of the “Hunnic” world was not their role as “military signs” “symbolizing severed heads of the enemies”, which was inherent among the Huns, as, for example, E. Ishtvanovich and V. Kulchar believed (1998: 9)*.

In 274 AD, the Emperor Aurelian carried out a religious reform aimed at reaching ideological unity of the Roman Empire: the cult of Sol Invictus Imperii Romani was combined with the cult of Mithra (Kulikova, 2020: 13). The sun officially began to be worshiped as one of the main deities. This “Hellenized cult”, which underwent transformation in Asia Minor, had only a distant relation to the Iranian Mithra, but nevertheless, according to R. Zuevsky, in the 3rd– 4th centuries it reached stunning proportions spreading from Spain to Germany, and from Britain to the eastern and North African provinces of the Roman Empire (2009: 28). Thus, the Aral-Caspian region appeared to be the area of both Western and Eastern (the cult of Mithra under the Sassanids) religious and philosophical influences. A new element emerged in the pictorial canons: a radiant crown around the head of the deity (and the king). An example is the image on the twosided relief from Rome (Ibid.) or bas-relief depicting Artashir II and Mithra (Lukonin, 1969: Fig. 19). Gold is tied with the sun, which is tied with the ruler. The artisan could have tried to represent precisely such a “radiant crown” around the head on the masks from the Karakabak burial (see Fig. 7, 6–9). And “hair” on the masks from the Volga region and North Caucasus was shown in such distinctive, wide, upward bands in relief precisely for this reason.

Thus, we can state that the headband with masks from burial 11 at the Karakabak cemetery was the imitation of a diadem—a sign of royal dignity. “Simplified” forms of such diadem headbands with a round forehead plaque can be seen in the portraits of Roman and Byzantine emperors (see (Zasetskaya, 2011: 48, ill. 20)), and sometimes they have two more additional plaques on the temples. Speaking about the geographically closest parallels, we can mention the headband decorated with sewn-on hemispherical plaques from the Late Sarmatian hoard found at the shore of Lake Batyr (Eastern Caspian region) (Skalon, 1961: Fig. 4, 4–6). However, while according to its stylistic and technological canons the Karakabak forehead plaque is undoubtedly an imitation of the Late Roman (Hellenistic) models, the temporal maskplaques from the headdress, made in high relief with the rendering of facial features, oddly enough, are closer to Pazyryk counterparts (see (Rudenko, 1953: Pl. XLIII, LXXX, 6, 7)). We should keep in mind that the artisan who made the Mangyshlak plaques had sufficient skills in woodworking. However, the Caspian semi-desert region does not have an abundance of forests, and more traditional casting and toreutics were applied. A foreign woman could have been buried in Karakabak burial 11, and this explains such radical difference between her outfit and grave goods of clothing complexes from other burials at that cemetery. As for the anthropomorphic images, their division (“male” and “female”, “father” and “mother”, “Mongoloid” and “Caucasoid”) is rather arbitrary and unsubstantiated. A well-grounded interpretation is difficult, since in this case the dichotomy of left and right is not associated with any ethnic differentiation. The stereotypes known from archaeology and ethnography do not work, because the use of mirror images on items was typical of the majority of traditional outfits (headdresses). Only the image of closed eyes in the context of the funeral ritual and display of some (possibly!) ethnic component in the faces may (if more similar finds come to light) reveal a different, more detailed level of interpretation in the future.

Conclusions

The analysis of the burial complex and grave goods in this article has made it possible to formulate several important points.

-

1. Burial 11 of the Karakabak-10 cemetery is dated to the second half of the 5th to early 6th century and belongs to a nomadic noblewoman.

-

2. Specific aspects of funeral rite are typical of the Late Sarmatian circle of sites, while the grave goods show some features typical of the post-Hunnic, “Shipovo horizon”.

-

3. The identical nature of the Karakabak and Altynkazgan finds may be explained by an artisanal center in the settlement of Karakabak (for more details, see (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2019)) located nearby.

-

4. Belt buckles, shoe buckles, and elements of headdress were made specifically for the ritual and were not used in everyday life.

-

5. The outfit of the girl from burial 11 is not associated with the “Pontic fashion”, whose influence can be observed in the evidence of other burials explored at Karakabak. On the one hand, the headdress (cape with sewn gold plaques and diadem headband with anthropomorphic images) was an imitation of royal vestment reproducing Late Roman (Hellenistic) models. In this sense, the statement of S.A. Yatsenko, who asserted that “diadems of nomads are not accompanied by the headdress, being an independent element of the outfit” (1986: 14) is incorrect. On the other hand, certain stylistic features of the carved wooden masks point to some Central Asian context. This suggests that a foreign girl who was not of Sarmatian-Alanian origin was buried in burial 11. This assumption will undoubtedly be further corrected after carrying out genetic studies.

Acknowledgments