Burials in anthropomorphic jars in the Philippines

Автор: Tabarev A.V., Patrusheva A.E., Cuevas N.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145429

IDR: 145145429 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.2.040-047

Текст обзорной статьи Burials in anthropomorphic jars in the Philippines

The Philippines, along with Indonesia, East Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and East Timor are a part of Maritime Southeast Asia. Special features of the dynamics of ancient cultures on the islands of the Philippine archipelago are determined by its geographical location within the tropical belt, as well as by variously directed migration and technological impulses from the mainland territories of East and Southeast Asia.

Until recently, archaeology of the Philippines was only rarely mentioned in Russian publications, such as the summarizing papers “The Old Stone Age in South and Southeast Asia” by P.I. Boriskovsky (1971: 161–162) and “The History of the Philippines: A Brief Overview” by Y.O. Levtonova (1979: Ch. I); the results of archaeological search and the discoveries of the last 25–30 years are actually unknown to Russian specialists. This situation has started changing considerably in recent years: along with a mutual common interest of the Russian

and Philippine scholars in collaborating at the level of special agreements and options for implementation of joint projects under national science foundations*, a separate (“Philippine”) theme is gradually being formed in publications of Russian archaeologists, including the present authors (see, e.g., (Tabarev, Patrusheva, 2018; Tabarev, Ivanova, Patrusheva, 2017; and others)).

Of special interest is a variety of funerary practices on the islands of the Philippine archipelago. A tradition of burials in jars stands out among them. First versions concerning the origins of this tradition appeared as early as the mid 20th century. Thus, for example, O. Beyer associated its occurrence on the Philippine Islands with migrations from the southern regions of China through the Batan and Babuyan Islands to the north of Luzon Island, at the turn of the eras, while W. Solheim attributed it to the cultural diffusion from Indochina, Thailand, and the Malay Peninsula (Beyer, 1947; Solheim, 1970, 1973). Thus far, the earliest manifestations of the tradition of burials in jars have been recorded in Late Neolithic assemblages (ca 3 ka BP), while individual elements remain unchanged up to our times. On the one hand, they fit into the Late Neolithic and Early Metal Age system of burial rites that is common for the entirety of Southeast Asia (Tabarev, 2017a; Bellwood, 1997: 202; 2017: 327; Bulbeck, 2017); and on the other hand, Philippine assemblages demonstrate a number of unique practices. First of all, this applies to burials in anthropomorphic jars in Ayub Cave on Mindanao Island (Fig. 1), which are dated to 500 BC to 500 AD.

In fact, this article is the first experience of joint work performed by Russian and Philippine archaeologists. It considers the burials in jars from Ayub Cave as part of the “anthropomorphic” theme in the funerary practices of Maritime Southeast Asia and in a broader Pacific context.

Anthropomorphic jars in the funerary assemblages of Mindanao Island, Philippines

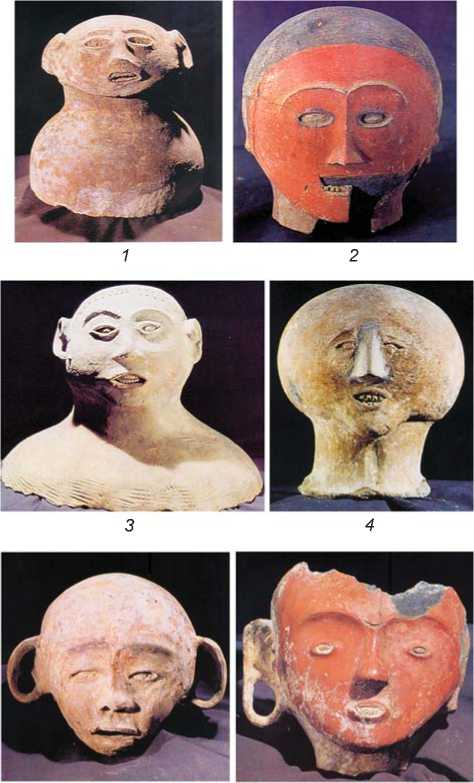

Mindanao Island (whose area is slightly less than 100 thousand km2) has been only preliminarily studied in terms of archaeology. Among the earliest projects were studies conducted in 1963–1964 and 1967 under the supervision of M. Maceda in the Kulaman Plateau (Sultan Kudarat Province), where excavations were carried out in several caves, and a series of funerary clay vessels

*For example, in August 2018, an agreement for cooperation in science and technology, the first in the history of Russian-Philippine contacts, was signed between the Russian Foundation for Basic Research and the Philippines’ Department of Science and Technology.

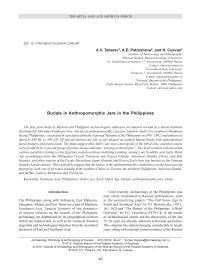

Fig. 1. Map of the Philippine archipelago, with indication of locations of the main sites mentioned in the text.

1 – Ayub Cave; 2 – Magsuhot; 3 – Tabon.

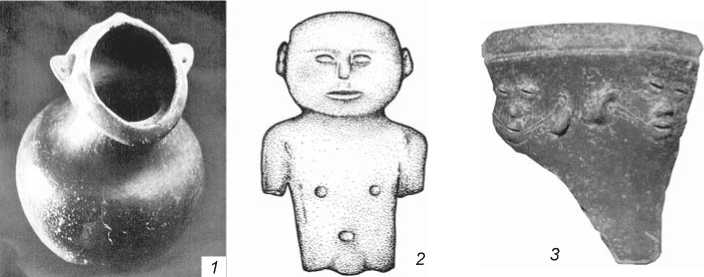

and soft-stone urns with remains of buried people, items made of stone and shells, and several metal artifacts were found (Maceda, 1964, 1967). Of special interest are stone urns with anthropo- and zoomorphic subjects (figures of humans, lizards, snakes) (Fig. 2).

In 1965–1966, S. Briones, a postgraduate student of Silliman University, visited the Kulaman Plateau and noted the presence of stone funerary urns and ceramic vessels in Salangsang caves and niches (Briones, 1985– 1986). Soon after this, in the 1967–1968, American specialists E. Kurjack (University of Miami) and K. Sheldon (University of Oregon) conducted additional studies in the same areas, and dated a bone fragment from a burial in a jar (585 ± 85 AD) (Dizon, 1996: 195; Dizon, Santiago, 1996: 10; Kurjack, Sheldon, Keller, 1971: 127– 128). At the end of the 1970s, W. Solheim, A. Legaspi, and D. Neri published a review paper on the archaeology of the southeastern part of Mindanao (Solheim, Legaspi, Neri, 1979), following which field studies on the island were interrupted until the beginning of the 1990s.

In the middle of 1991, the first data appeared on the anthropomorphic burial jars found in abundance during searches for “treasures”* in one of small caves in the

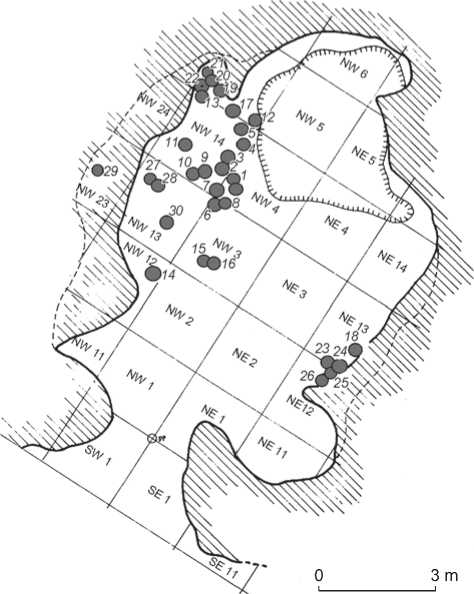

Fig. 2. Burial urns with anthropomorphic symbolism, the Kulaman Plateau (photo from the authors’ archive).

Province of South Cotabato. According to E. Dizon, he managed to see some of these materials, which included 25 ceramic items (lids of jars) in the form of human heads up to 7–14 cm high, up to 6–12 cm in diameter, and 0.2–0.5 cm thick (1996: 191). Details (ears, noses, lips) were made with different techniques: as individual appliqué patterns or as a unified sculpture form; some items were painted red and black; red engobes were also present on the most fragments of the jars themselves.

Archaeological excavations in the cave, which was called Ayub*, were conducted by the team of the National Museum of the Philippines in 1991–1992. The preentrance part of the cave has a height of about 3 m with a width of 5 m; the internal cavity descends from the entrance at an angle of 30° by approximately 8 m. The “treasure hunters” destroyed the pre-entrance part using heavy equipment, and excavated test pits in the internal cavity of the cave. Nevertheless, archaeologists managed to discover several square meters of undisturbed cultural layer (Fig. 3), where 29 nearly-complete jars with lids in the form of human heads, as well as about 20 lids restorable from larger parts, and more than 100 various fragments, were found during excavations. According to Philippine specialists, in general, there were about 200 anthropomorphic lids of funerary jars (Cuevas, Leon, 2008; Dizon, 1996: 191; Dizon, Santiago, 1996).

Notably, the faces of ceramic heads show various emotions: smiles, grief, sorrow; some of them have distinctively elaborated parted lips, teeth, and extended earlobes, with paint on the forehead and cheeks clearly visible (Fig. 4). Sexual characteristics designated on the jars themselves allow male and female images to be distinguished (Fig. 5). Thus, a ceramic jar not only serves as a funerary container, but also provides certain information about the buried person or persons.

Funerary urns were accompanied by small jars painted red and black and decorated with spatula and cord imprints, as well as with incised geometrical figures. Grave goods comprise glass and ceramic beads, fragments of ceramic bracelets, ornaments made of shells, and several small iron plates.

Two radiocarbon dates (1840 ± 60 BP (Beta-83315) and 1900 ± 50 BP (Beta-83316) (Dizon, Santiago, 1996: 109)) make it possible to assign the use of the necropolis in Ayub Cave to the turn of the eras, i.e. to the time defined as the Early

Metal Age in the archaeological literature on Southeast Asia, and as the “Metal Period” with respect to the island part, since bronze, iron, and gold appeared here almost simultaneously. So far, the number of sites belonging to this period is insufficient to distinguish full-fledged

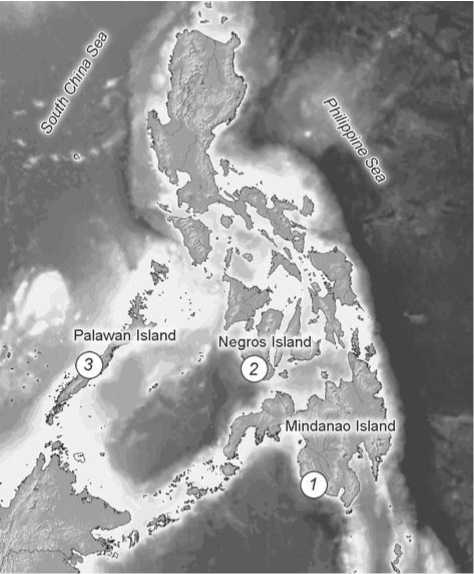

Fig. 3. Arrangement of burial urns found during excavations in Ayub Cave in the 1991–1992 (adapted after (Dizon, Santiago, 1996)).

Fig. 4. Anthropomorphic lids of burial jars from Ayub Cave (after (Dizon, Santiago, 1996)).

“archaeological cultures” in the territory of Philippines, so specialists use the terms “assemblage” and “tradition” at this stage (Handbook…, 2017: 6–7).

Anthropomorphic jars from Ayub Cave and their nearest parallels

Owing to the partial preservation of the assemblage in Ayub Cave, the absence of data on DNA, and detailed anthropological definitions, the interpretation of the assemblage and its ethnocultural relation to the present aboriginals of Mindanao has a preliminary character. It is also notable that the adjacent Sagel Cave, pertaining to the same period, does not contain any anthropomorphic funerary jars. Besides, though Ayub is dominated by group burials, Sagel accommodates only single ones (Cuevas, Leon, 2008). All of this points to the variability of burial rite details within the framework of a common tradition.

Fig. 5. Burial jars from Ayub Cave (after (Dizon, Santiago, 1996)).

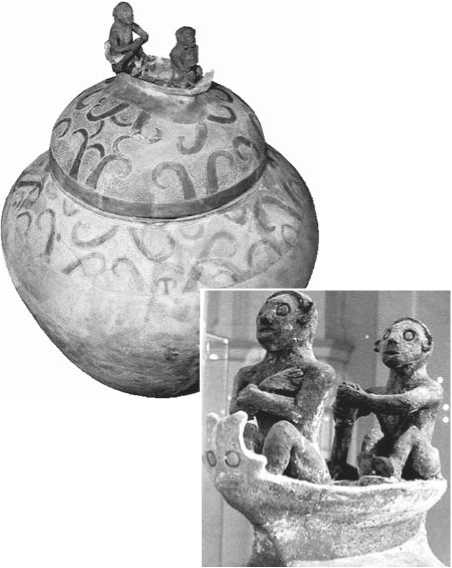

At the same time, finds in Ayub Cave, despite their vivid specifics, uniqueness, and local character, also reflect anthropomorphic subjects in grave goods, which are common for Maritime Southeast Asia. Noteworthy are the most spectacular examples within the Philippines and Indonesia. For instance, one of the most ancient manifestations of an anthropomorphic subject was found in Tabon Caves (Palawan Island, Philippines), in hall “A” (Fox, 1970: 109). We are talking about the famous Manunggul burial jar. Its height is 66.5 cm, the maximum width is 51 cm. The jar’s lid is surmounted with a sculptural composition depicting two dead people, who are moving to the kingdom of the dead in a boat (Fig. 6). The funerary urn was accompanied by artifacts made of jade, agate, and shells, as well as several small clay vessels. There are 891 ± 80 (USLA-992A) and 711 ± 80 (USLA-992) BP dates available for this assemblage, which corresponds to the Late Neolithic, or the transition to the Early Metal Age for the Philippine archipelago (Tabarev, Ivanova, Patrusheva, 2017).

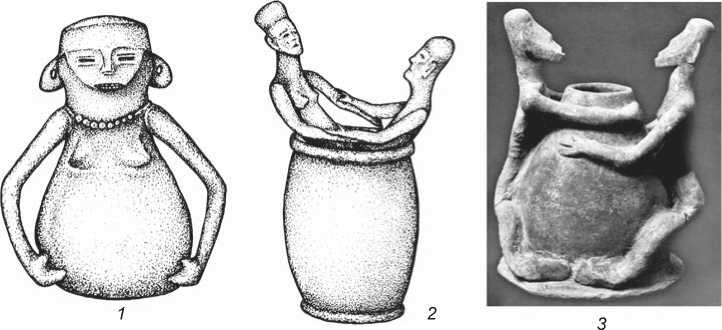

For the Early Metal Age (Metal Age), extremely interesting materials were obtained in 1974–1975, when studying the Magsuhot site (the southern part of Negros Island, the Philippines) (Tenazas, 1974), where common (single) and two “complicated” funerary complexes were discovered. One of them accommodated a ground of 2 × 1 m, paved with flat ceramic fragments, where three large empty burial jars were placed, accompanied by a set of more than 80 small ceramic vessels, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sculptures, a burial of a woman and two children, and a single stone block weighing ca 500 kg. Of special note is a jar depicting a pregnant woman (Fig. 7, 1 ), and also jars with lids in the form of a paired composition consisting of sitting or standing figurines (Fig. 7, 2 ).

Fig. 6. Manunggul burial jar from Tabon Caves (photo from the authors’ archive).

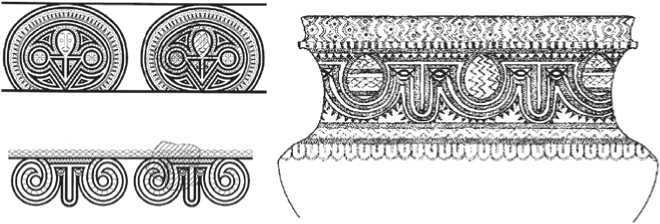

Certain ceramic items with anthropomorphic symbolism are also known from other Philippine sites belonging to the Early Metal Age (Leta-Leta, Baja, Kalamaniugan, Kalatagan, etc.) (Fig. 8, 1 , 2 ). No less interesting parallels can be traced on the islands of Indonesia. For example, noteworthy is the Pain Haka site (the eastern part of Flores Island), where 13 single burials (mostly partial, without skulls) in jars were found. All jars, with one exception, are of spherical shape, with red engobes; some of them have incised ornaments; in one case, decoration of the upper portion of the body with appliqué patterns in the form of human faces (Fig. 8, 3 ) is recorded, and in another one, representations of lizards. Grave goods include sub-rectangular adze-like tools made of stone or shells, bracelets, beads, and pendants made of shells, plus a spine of a sea skate. Metal items are absent, and radiocarbon dates determine the necropolis’s age within 3000–2100 BP (Galipaud et al., 2016).

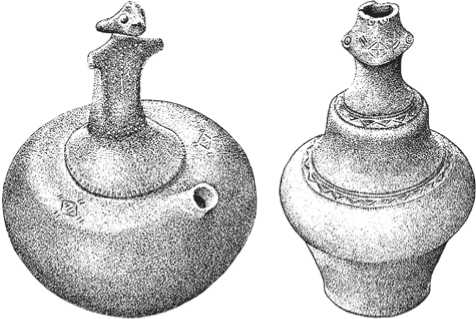

A series of “candy” jars in the shape of flasks or kettles with relief or incised contours of human faces, known from a number of funerary assemblages on the Sumba, Flores, and Java islands, is of no less interest (Heekeren, 1958: Pl. 34) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7. Burial jars from the Magsuhot site (drawing by Y.V. Tabareva, photo from the authors’ archive).

Fig. 8 . Anthropomorphic images from funerary assemblages of Maritime Southeast Asia.

1 – Leta-Leta, Palawan Island, the Philippines (after (Dizon, Santiago, 1996)); 2 – Baja, Luzon Island, the Philippines (drawing by Y.V. Tabareva); 3 – Pain Haka, Flores Island, Indonesia (after (Galipaud et al., 2016)).

Fig. 9 . Ceramic “candy” jars, Sumba Island, Indonesia (after (Heekeren, 1958)).

Conclusions

Thus, the assemblage from Ayub Cave (the southern part of Mindanao Island) is a telling illustration of one of the local funerary traditions of both the Philippine archipelago and the entire Maritime Southeast Asia. Analysis of its materials brings researchers to a wide range of interesting subjects.

First, burials in anthropomorphic jars can be interpreted as high-status, and the entire complex as a necropolis of the tribal elite. The grave goods, the “portraitness” of depictions, the complexity of the rite itself, and the absence of data about other funerary assemblages of such complexity in this part of Mindanao Island speak in favor of “elitism” (Barretto-Tesoro, 2003). Manufacture of vessels implies special skills and the existence of a group of potters using elaborate “prestige technologies” (Tabarev, 2008; Hayden, 1995).

Second, the question arises as to whether the anthropomorphic burial attributes are related only to ceramic items and to the period of transition of Neolithic pottery technologies from mainland parts of East and

Southeast Asia to the island part ca 4 ka BP; or whether they could have been preceded by local (pre-Neolithic) tradition of making figurines, masks, and amulets from organic materials. This requires a search for and special study of early funerary assemblages (10–5 ka BP) in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

Third, it is essential to involve a maximally wide range of archaeological and ethnographic parallels to the anthropomorphic symbolism within the Pacific Basin. The earliest ones are discovered in the early and middle periods of the Jomon culture (anthropomorphic

Fig. 10 . Jar depicting a human face, 70.2 cm high. Yayoi culture. Ibaraki Prefecture. Exhibition of the Tokyo National Museum (photo from the authors’ archive).

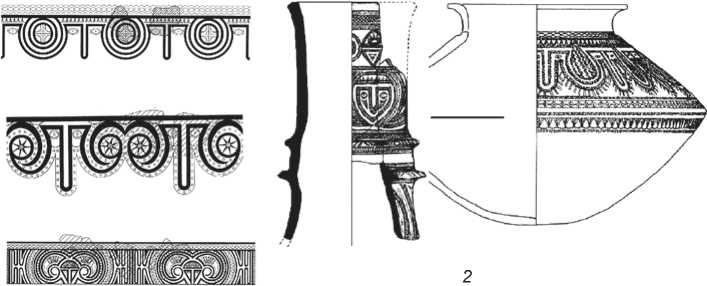

Fig. 11. Anthropomorphic symbolism of the Lapita culture.

1 – variants of ornaments on jars (after (Spriggs, 1990)); 2 – jars from Teouma cemetery, the Island of Efate, Vanuatu (after (Ravn et al., 2016; Valentin et al., 2010)).

images of “shamans”) and the Yayoi culture (stylization of the upper portions of jars in the form of human heads) (Fig. 10) in the Japanese Archipelago (Solovieva, Tabarev, 2013; Tabarev, 2017b), and in the Early Iron Age assemblages on the Korean peninsula, where paired burial jars are interpreted as a “human body” or an “egg” (Riotto, 1995).

And finally, an important event of cultural genesis for the entire Pacific Basin is the distribution of speakers of Austronesian languages from the coastal areas of southern China via Taiwan, the northern Philippines, Mariana Islands, and further south to Oceania (Carson et al., 2013). One of the markers of this migration is red-painted pottery with complex incised ornaments, which is also becoming the determining feature of archaeological assemblages recorded in Polynesia, Melanesia, and the Micronesia islands and combined into the Lapita culture (tradition) (3000–2500 BP). Notably, the anthropomorphic theme (symbolic representation of faces) is recorded in even the earliest pottery belonging to this culture; for example, in burials of the Teouma cemetery on the Island of Efate, Vanuatu (3.0–2.8 ka BP) (Bedford, Spriggs, 2007; Ravn et al., 2016; Valentin et al., 2010), and continues to persist with various modifications throughout the entire period of the Lapita tradition (Spriggs, 1990) (Fig.11), and also in the subsequent Polynesian cultural stratum.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. E. Dizon (the National Museum of the Philippines, Manila) for his help in working with literature and information on excavations in Ayub Cave, and to artist Y.V. Tabareva for the preparation of illustrative material for this article.