Ceramic “necklace”: a Neolithic ritual artifact from the Lower Amur

Автор: Medvedev V.E.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Paleoenvironment, the stone age

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Lower Amur, Neolithic, dwelling, sanctuary, Malyshevo culture, necklace, ritual items

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146814

IDR: 145146814 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.4.039-048

Текст статьи Ceramic “necklace”: a Neolithic ritual artifact from the Lower Amur

The large multicultural and heterochronous settlement site of Suchu Island in the Lower Amur (Ulchsky District of the Khabarovsk Territory) has been studied for many years and has become widely known. The underground remains of Neolithic dwellings allow for a graphic reconstruction of the interiors and the possible living conditions of the inhabitants. The collected materials (more than 93 thousand finds) clearly demonstrate the level of development of the material and the spiritual culture of gatherers, fishermen, and hunters of the Amur Region during at least the initial 6.5–7.0 thousand years of the Holocene.

Rich materials obtained during excavations of the settlement site have been described repeatedly in monographs and journal papers (Okladnikov, 1981; Derevianko, Medvedev, 2002; Okladnikov, Medvedev, Filatova, 2015; Medvedev, Filatova, 2020; and others). However, for various reasons, not all the study results of the 20 dwellings nor of the several sanctuaries (the latter constitute a single cult center on the island (Medvedev, 2005)) have been published to date.

This paper is a kind of continuation of the article recently published in this journal and devoted to dwelling 1 (excavation area II) excavated at the site in 1973 (Medvedev, Filatova, 2020). That publication mainly presented the results of multidisciplinary studies of the stratigraphy, the structural features of

the dwelling, and the abundant artifacts related to the life of its inhabitants—stone tools and clay pottery for everyday use. In the artifact collection of dwelling 1, a significant part consists of the items associated with the spiritual sphere—pieces of art and cult (portable art). These are well preserved, show unique characteristics, and deserve special consideration.

The dwelling was left by the Malyshevo people, likely in the late 5th to early 4th millennium BC. This is a semi-underground rounded structure typical of the Amur Neolithic, dug into the sandy loam virgin layer by 80 cm; it is rounded in plan view, with a floor of 55 m2 and a hearth in the center. The foundation pit showed many small pits from posts supporting the roof. Household pits were also noted. The total of 3788 items (intact and fragmented) made of stone or ceramics were found in the dwelling and next to it, including ceramic pieces of portable art (most of them intact) bearing mainly ornithozoomorphic images (pieces of art and cult), and other non-utilitarian items. Only a few of these have been described (see, e.g., (Medvedev, 2000: 62, fig. 6, 4–6 , 8–10 )).

During excavations of Neolithic dwellings at Suchu Island, with and without domestic sanctuaries, a large number of samples of primitive art have been found, including undoubtedly unique ones, such as, for example, gynandromorphic three-dimensional sculptural images of women with phallic bodies and the same hairstyle, a three-dimensional figurine of a seal-phallus-vulva and a flat figurine of an owl-bear (Ibid.: 57, fig. 1: 59, fig. 3, 1 ; 4; 2005: 52, fig. 19, 20). However, portable art pieces from dwelling 1, being cult items, still have no parallels in the known Neolithic assemblages of the Russian Far East. This is mainly true for the complex of miniature ornithozoomorphic figurines and other items that were elements of a kind of cult and ritual attribute—a “necklace”.

Analysis of other items of specific purpose, which are most likely older than the “necklace”, led to the conclusion that all together they constituted a certain single system—a domestic sanctuary with an altar at the western wall of the dwelling.

Location and composition of the “necklace” and other art and cult items in dwelling 1

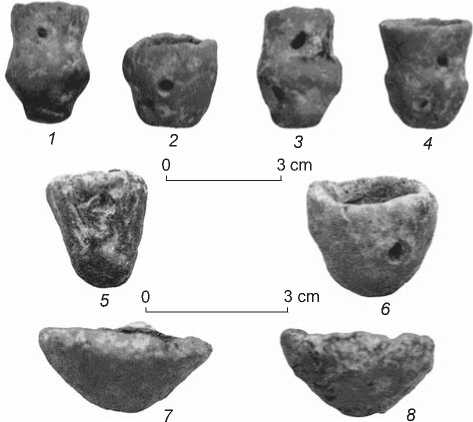

The “necklace” consists of 17 ceramic items, which formed a compact cluster in a small pit on the floor near the western wall of the dwelling, or rather under it. There is no doubt that the items constitute a single set and were hidden (buried?) intentionally. The

“necklace” includes eight small vessels, five figurines of flying birds, and four double-ended phallic figurines, each with the image of a seal head at one end.

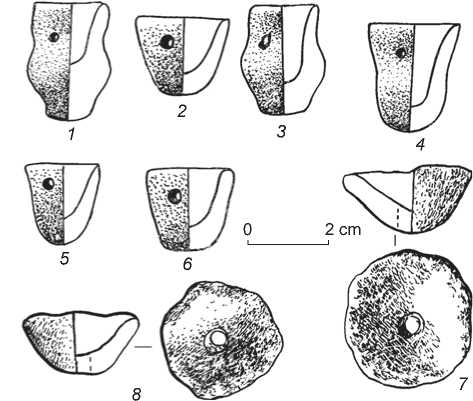

The vessels, like all other objects, were sculpted from a single lump of paste, the same that was used in the manufacture of household ware found in the dwelling (clay tempered with sand, sometimes grus and grog). They were made without apparent care; in some places, small knobs and dents are visible on their walls. Both internal and external surfaces were poorly smoothed. The ceramic shard is dense, firing is uniform, the color is mostly light brown, although there are samples with dark spots. All vessels show one, most often rounded, hole with a diameter of 0.2–0.3 cm (the holes in two cupshaped vessels are up to 0.5–0.6 cm). Holes were made before firing, by piercing with a rod from the outside inward. The holes were made in the upper parts of the vessels, 0.5–0.6 cm from the edges of the rims, which were not always neatly shaped; and in the cup-shaped vessels, they were made in the central part of the bottom. The thicknesses of the walls of the vessels vary: from 0.25–0.30 cm at the edge of the rim to 0.5–0.7 cm (in one pot-shaped vessel up to 1.5 cm) in the near-bottom and bottom parts; in cup-shaped 0.3–0.5 cm, with the bottom somewhat thicker. The bottoms of all the vessels are mostly flat, with some irregularities; there are items with slightly convex bottoms. The vessels are largely copies of ordinary household ware.

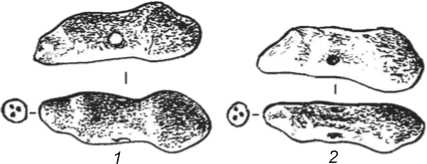

The vessels have been subdivided into three types: 1) situla-shaped – 3 spec. (Fig. 1, 2 , 5 , 6 ; 2, 2 , 5 , 6 ), 2.0– 2.1 cm high, the rim diameter is 1.9–2.3 cm; two items have flat bottoms (0.9 cm); one item shows a convex bottom; 2) cup-shaped bowls like hemispheres – 2 spec. (Fig. 1, 7 , 8 ; 2, 7 , 8 ), 1.6 and 1.7 cm high, the rim diameter is 2.8 and 3.1 cm respectively, the bottom is 0.7 cm, the walls are even, smoothed, and the rim surfaces are bumpy with notches; 3) high pots – 3 spec. (Fig. 1, 1, 3, 4 ; 2, 1, 3, 4 ); these have well-defined bodies, the diameters of which are the same as those of the mouths, or slightly larger. The high pots look not as similar in shape to Malyshevo vessels of this type as the situlas and bowls/cups. This may indicate that the artisans producing copies paid more attention to the essential, practical side of the products rather than to their external, formal features.

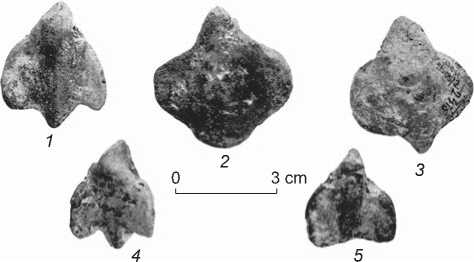

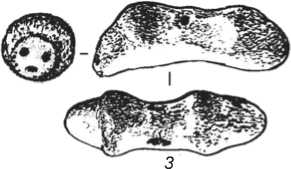

Birds are depicted in a state of flight. All of them belong to the auk family of diving seabirds*. Three

Fig. 1. Ceramic vessels constituting the “necklace”.

Fig. 2. Vessel drawings.

larger figurines, 3.6 to 4.1 cm long and 3.1–4.1 cm wide (wing spread), likely depict adults (Fig. 3, 1–3 ; 4, 1–3 ). They are relatively massive, the wings have rounded outlines, the edges and heads are noticeably lowered. In two figurines, the lower surface (from the side of the abdomen) is flat, and the upper one is rounded, while the third figurine shows convex and uneven surfaces, respectively. Smaller figurines (Fig. 3, 4 , 5 ; 4, 4 , 5 ) are 2.9 and 2.6 cm long (the tail of the second figurine is missing) and 2.5 and 2.4 cm wide, respectively. The edges of their wings are raised; the head is shown above the back. The tails of all the figurines are short, in the form of a rounded triangle. The beaks of three larger specimens are blunt, while those of two smaller specimens are pointed, and are shown in the open state, as when eating. The large figurines were shaped more carefully than the small ones. The surfaces of larger figurines are well-smoothed as compared to that of the smaller figurines. The color of the figurines is the same on both sides, varying from brown and grayish brown to dark, in some places black. The difference in the shapes and sizes of the figurines suggests that the artisan was well-acquainted with the features of birds’ appearance; therefore, along with adults, he depicted young birds so naturally and professionally. All figurines had a through hole 0.2–0.3 cm in diameter made in the head using a round rod prior to firing. The bird figurines suspended on a cord or rope in this position looked as if they were flying upwards.

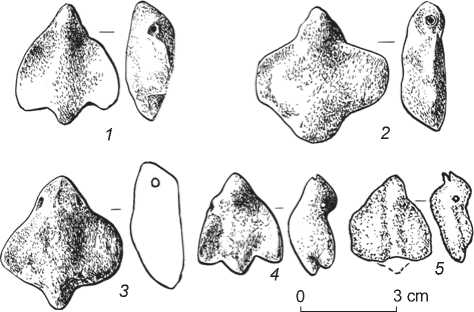

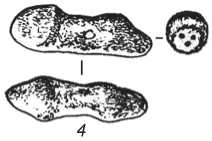

Four figurines of double-ended phalli, each depicting a seal head at one of the ends (Fig. 5) are

Fig. 3. Ceramic figurines of flying birds constituting the “necklace”.

Fig. 4. Bird figurine drawings.

of different sizes: length 2.8, 3.2, 3.4, and 3.9 cm, the maximum thickness is 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.4 cm, respectively. Their color is dark gray and brown. The figurines are carefully modeled with the help of a thin spatula and a rod. They are slightly curved. The heads of each figurine are of different sizes. The smaller one is thinner and slightly elongated; on its end, a seal head is rendered quite realistically, with eyes and a mouth depicted by rounded dimples. The opposite ends of the figurines, with more voluminous heads, have smoothed flat surfaces without any decoration. Round through holes (prior to firing), with a diameter of 0.20–0.25 cm, were made in the central parts of the items. Each hole is closer to the end with the seal head. Thus, when hanging figurines on a string or cord, the parts with the animal images turn out to be facing upwards.

Having presented a description of all 17 elements making up the “necklace” (Fig. 6, A ), I cannot but express doubts about its completeness. This is due to the fact that three slightly smaller vessels (two potshaped and one cup-shaped) were found scattered on the floor of dwelling 1, a little away from the pit where the items constituting the “necklace” were found; these vessels are generally similar to those described above and each has one round hole in the body or bottom (Fig. 6, B ). The pot-shaped vessels are roughly shaped. Their bottoms are uneven with bulges, the rim edges are bumpy from the inside, so the mouths are barely visible, the outer surfaces are only partially smoothed, and the inner ones were not treated at all. These three vessels could have been parts of the “necklace”, but somehow got separated from it. However, the obvious incompleteness in the design of these items does not allow them to be included in a set where all the objects have finished forms.

0 3 cm

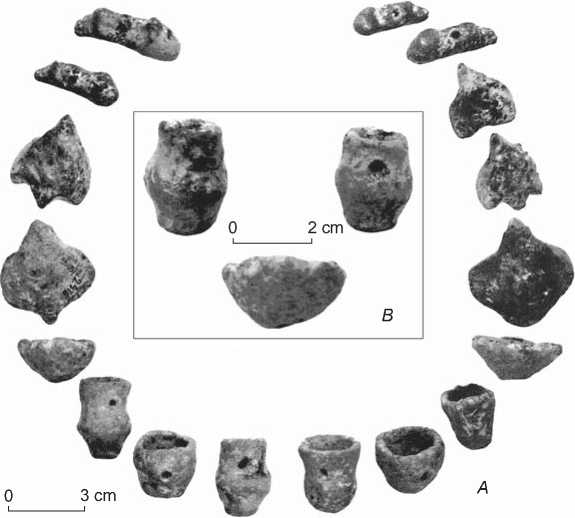

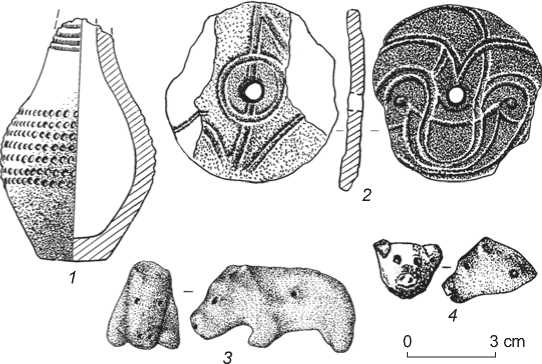

The works at dwelling 1 showed that the sanctuary occupied a much larger space than the pit with the “necklace”. It covered a stretch of ca 5 m along the western wall. Here, on the floor or slightly deepened into it, clay cult and ritual (sacred) items were randomly located (Medvedev, Filatova, 2020: 5, fig. 1, B ). Among these, the following objects are noteworthy. A small vessel with an egg-shaped body and a narrow neck bears no traces of use for utilitarian purposes. Its rim is missing. Vessel height is 8.2 cm, body diameter 5.3, bottom diameter 2.3, that of the neck 1.9–2.1 cm, wall thickness 0.5 cm, bottom 0.8 cm thick (Fig. 7, 1 ). Its color is reddish-yellow, the central part of the body is decorated with seven rows of rounded pit impressions; four rows of small vertical incisions are preserved at the top of the neck.

A disc-shaped item, 6.1 cm in diameter and 0.4–0.5 cm thick, with a small part missing, and one side partly exfoliated (Fig. 7, 2 ). The item is convex-concave, dark in color. In the center of the disc, there is a through hole with a diameter of 0.5– 0.6 cm. This item is similar in general outline to the well-known Neolithic spindle whorls of the Amur region. However, those spindle whorls are usually more robust and thickened in the central part. The ornament is often found only on their convex surfaces. The disc under consideration shows grooved-carved ornaments on both sides. Its convex surface bears a stylized syncretic face with large fish eyes, in which pupils are marked with round dimples 0.4 cm in diameter. Eyebrows converging on the bridge of the nose form a V-shaped figure (female childbearing symbol?). The phallus-shaped nose is superimposed on an exaggeratedly enlarged crescent-shaped mouth. The reverse side shows what appears to be a quadrangular figure resembling a rhombus, and a circle around the hole, both crossed by a vertical line. The disc-shaped item is a lamellar churinga. On its convex surface, it apparently shows a syncretic religious and mythological image of a bisexual anthropomorphic creature, and on the opposite

Fig. 5. Ceramic figurines of double-ended phalli, with the image of a seal’s head at one end, constituting the “necklace” ( A ), and their drawings ( B ).

B

3 cm

Fig. 6. The hypothesized look of the “necklace” ( A ), and ceramic vessels ( B ) found close to the accumulation of the “necklace” elements.

side, a circle and possibly a rhombus, which are traditionally interpreted as solar symbols. Churingas occurred in the Lower Amur region during the period of the Malyshevo culture; some items of this type were found on Suchu during excavations of several Malyshevo dwellings (Medvedev, 2000: 67, fig. 8; 2002: 13, fig. 1, 1–7 ).

A figurine combining the images of a bear’s head and a small animal, 2.9 cm long, 2.1 cm wide, and 1.7 cm high (Fig. 7, 4). The characters are shown over equal parts of this miniature figurine. The muzzle, obviously, of a young bear is depicted. It is narrowed, slightly elongated, the forehead is steep, the eyes are in the form of round deep dimples, the nostrils are punctate depressions, the mouth is slightly open, the upper halves of the ears are missing. The opposite side shows the head of a small animal (possibly a squirrel or a chipmunk). From the ears, belonging to the both characters, it gradually narrows, turning into a narrow, pointed nose, which is not shown in details. Prior to baking, approximately in the place of the eyes of the animal, a neat round through hole with a diameter of 0.25 cm was made. The hole was possibly intended for threading a cord. The surface of the figurine is carefully smoothed and coated with red ocher, especially on top; the ocher coating is poorly preserved.

A sculpture of a bear in a static standing position, 5.5 cm long, up to 2.4 cm wide, and 2.9 cm high (Fig. 7, 3 ). It is fairly evenly baked; the color is light brown on the surface, and dark gray in the fracture. The item shows artisan’s fingerprints. The muzzle and the whole head of the animal are relatively robust. Two paws (the front left paw partially, the right one completely) and both ears (almost to the base) are broken off. The eyes and nostrils are marked with round deep dimples, the mouth is tightly closed. Before firing, two holes were made in the central part of the figurine: the axis of the first hole is horizontal (from one side to the other); the second is vertical (from the back to the belly). It is quite possible that the first hole was not good enough; therefore, the artisan made the second one. This fact suggests that all the non-utilitarian items found in the sanctuary and near it must have had proper holes.

In addition, the following ceramic items were found on the floor, some of them a little higher, in the low layer of the foundation pit filling, mainly in the western part of the dwelling. In a small depression, a female figurine with a realistically depicted face was found. The head, with a chignon hairstyle (the top was broken off in antiquity), is phallus-shaped in side view. A through hole was made in the head (Medvedev, 2000: 59, fig. 3, 2). A small intact phallic rod, seven fragments with an oval-rounded cross-section, a broken sandstone phallic item with a female symbol on the end, and three

Fig. 7. Ceramic items from dwelling 1.

1 – vessel; 2 – disc (churinga); 3 – bear figurine; 4 – three-dimensional sculptural image combining the head of a bear and a small animal.

tripoli labrets were also found (Medvedev, 2005: 55, fig. 28, 3, 4 ).

Notably, the above items, which were scattered away from the rather compactly formed sanctuary, have various ancient damages (broken off edges of the disc-churinga, ears and paws of animal figurines, the top of the chignon of a female figurine, broken rods). All the ceramic items (with the exception of a vessel apparently intended for storing some kind of drink, possibly alcoholic, and rods) have round through holes. It is quite possible that these items, which are not spatially connected with the central part of the sanctuary, where the “necklace” was located, could have been (before the appearance of the “necklace”) a part of another complex ritual and ceremonial attribute, similar to the “necklace”, or could have been used as sacral pendants on the clothes (belt) of the inhabitant of dwelling 1 who performed the rituals.

Interestingly, the things that I consider older showed, in addition to damage (probably intentional breakdowns, in contrast with the “necklace”), traces of long-term use in the form of wear and polish. This suggests that the figurines, the sculpture, the disc-churinga, and others, which served as the main sacred symbols for a long time, although they were kept in the dwelling, were replaced or supplemented with new objects of worship in the sanctuary. Perhaps, the replacement of the former important cult and ritual attribute occurred owing to the change (possibly death) of the performer of ceremonies. Most likely, the items of the “necklace” set became the main ritual objects.

Appearance and functional characteristics of the “necklace”

The name of the cult and ritual attribute under consideration is put in quotation marks, since it is more common to associate this name with a neck ornament made of precious pieces (mainly stones). But in this case, the set consisted of ceramic pieces, and was not a neck ornament in the literal sense; nevertheless, it was intended, apparently, to be put on the neck when necessary.

It is hardly necessary to dwell in detail on the issues of the existence of sanctuaries in the Lower Amur region throughout the entire period of the Neolithic cultures in the region, which had been developed from the Final Pleistocene for at least ten thousand years. It has been shown that in almost all identified cult centers (Sakachi-Alyansko-Gasinsky, Voznesensky, at Suchu Island, Takhtinsky), in semi-dugout dwellings or pseudo-dwellings, there were home sanctuaries. These were used not only as storage places for various cult, ritual, and sacrificial objects, but also, presumably, as places for seasonal holidays to venerate the forces of nature, with a focus on fertility. Productive rites, inherent to initiation rites—initiation of young men into the status of adults—were obviously important for the inhabitants of the studied Neolithic dwellings in the Amur region. More detailed discussions of the subject, which also includes the issues of the origin in the Lower Amur Early Neolithic and the long-term existence of polyeiconic and polysemantic art, the appearance of inherently archaic bisexual anthropomorphic, phallic, and anthropozoomorphic images reflecting the original ideology and worldview of the region’s inhabitants, have been presented elsewhere (Medvedev, 2000, 2001, 2005).

Home sanctuaries (places of worship or secluded areas) have been discovered at random, as a rule. In the course of excavations, it is difficult to distinguish sanctuary attributes from the total mass of artifacts, which were not always located in the same places in the dwellings where they were situated during the life of the inhabitants. In addition, sacred objects did not often lie compactly but made up certain series. Researchers rightly note that sanctuaries could have been established in all or almost all ancient dwellings, but for the above reasons they are identified relatively rarely.

The artifacts from dwelling 1 at Suchu Island undoubtedly arouse considerable interest. Various impressive items described above have been preserved; moreover, an unusual “necklace” has survived almost intact after deposition in the sandy loam for millennia. The “necklace” is a set of 17 miniature items for ritual and ceremonial purposes (another possible use, for example, as children’s toys, is hardly reasonable, because the entourage recorded during the excavations, the “range” of other objects of cult art, testifies to the sacred nature of this unique find).

Suggesting a possible version of the order of arrangement of the elements of the “necklace”, I do not insist that it was exactly as shown in Fig. 6, A . However, this reconstruction is based on a number of reasons. The set is dominated by small vessels— imitations of the household ware of the Malyshevo culture, to which culture the inhabitants of the dwelling belonged. The vessels were most likely in the center of the “necklace”.

The available data of historical and archaeological research inform us that ceramic vessels made with the help of fire (a mysterious power) were given a special semantic content in primitive societies. The vessel was often regarded as a symbol of wealth and prosperity. Presumably, a similar conceptual religious-mythological idea, archaic in nature, was also popular in the Neolithic communities of the Amur region. Interestingly, the vessels in the “necklace” are rendered not schematically but with many details indicating their practical use: tall pots – for storing food and drinks; containers in the form of situlas – for cooking (on fire); cup-shaped vessels – for eating.

The second-largest category of images in the “necklace” is the figurines of birds, which, being strung on a cord, apparently adjoined the vessels. The presence of ornithomorphic sculptural images in a composite cult and ritual attribute is quite understandable. Since ancient times, the cult of birds has been widespread among many hunting and fishing communities of Siberia and the Far East. Various tribes and peoples considered both forest birds and waterfowl as their totems, to which ritual actions were dedicated. According to the data from excavations of dwellings with sanctuaries, the owl was revered in the Neolithic of the Lower Amur region. A fragment of a ceramic figurine of this bird was found in the Takhta cult center (Medvedev, 2005: 58, fig. 31, 2 ), and a flat stone sculptural polysemantic image of an owl-bear (Ibid.: 52, fig. 20) was discovered in sanctuary 1 at Suchu Island. Both finds were attributed to the Voznesenovskoye culture. At Suchu Island, in dwelling B of the Malyshevo culture, a ceramic ornithomorphic figurine, possibly depicting a duck, was found (Okladnikov, 1981: Fig. 58). A flint figurine depicting a pine-forest bird found at the Sakachi-Alyan site (Lower point), in the destroyed layer of the Osipovka culture, can be listed among the earliest ornithomorphic pieces of portable art in the region. Its approximate age is at least 10 thousand years (Ibid.: Fig. 49; Okladnikov, 1971: 86). A shale figurine of an owl from the settlement of Gasya belongs to the same culture (Derevianko, Medvedev, 1995: 17, fig. 46, 1 ).

Without discussing in detail the region-wide Far Eastern issue of the origin and development of ancient artistic and religious traditions associated with birds (this is a separate topic of study), I note that the finds from the residential sanctuary at Suchu Island show the great importance attached by the dwellers to birds of the auk family, the inhabitants of the sea coasts (by the way, Suchu is located 50–55 km from the Strait of Tartary). It is unlikely that these birds were among the prey of the inhabitants of the island and the banks of the Amur. The people were apparently fascinated primarily by the perfect features of the sea hunters. Therefore, the ancient artisan depicted auks so carefully and realistically. The birds in the “necklace” obviously performed the role of a magical influence and attractors of good luck in the vitally important pursuits of fishing and hunting.

The next-largest category comprises doubleended phallic figurines with the image of a seal head at one end. Their smaller number does not mean that these figurines were less important in the ritual and ceremonial attribute. The figurines expressively and substantively embody the wide-spread ancient idea of fertility and reproduction of game animals, namely the pinnipeds. These animals were the object of marine hunting in some areas of the Amur valley away from the Pacific coast as early as in the Middle Neolithic. The people of the Malyshevo and then Voznesenovskoye cultures admired their ability to swim and fish, and valued seals as a source of fat, meat, and skin.

Describing the “necklace” as a whole, we should pay tribute to the artisan, who expressed the religious and mythological ideas of primitive man about the prerequisites for his prosperous existence. This sacred affiliation is the quintessence of the existence of groups of people of a particular geographical area.

The above-mentioned artifacts scattered over the western part of the dwelling and at the wall deserve a detailed interpretation. All of them could have been connected with the main part of the sanctuary, where the somewhat younger “necklace” was found. These artifacts include a group of phallic items and a similar image on the churinga. The cult of the masculine principle, recorded among many cultures, is evidenced by the multiple finds related to this during excavations at Suchu and other Neolithic sites of the region.

The bear was a particularly revered animal in the Far East, as evidenced by its sculptural images found in the dwellings and sanctuaries in the Lower Amur basin. A hybrid figurine consisting of a bear’s head and a small animal from dwelling 1 is unique; the figurine refers to an earlier time in the sanctuary use than that of the “necklace”. This find is one of the confirmations of the existence of polysemantic art in the Lower Amur Neolithic.

In historical and archaeological studies of a wide geographical range, much attention is traditionally paid to the artistic and cult image of a woman, which originated in the Upper Paleolithic and developed in the Neolithic and successive periods. In the Far East, the earliest stone figurines of bisexual hybrid images (phallus-woman) in the Lower Amur region are known from the Early Neolithic Osipovka culture materials at the sites of Sakachi-Alyan and Kondon (Pochta) (Medvedev, 2001: 78, fig. 1, 2; p. 80, fig. 5; p. 81, fig. 6), as well as at the settlement of Goncharka-1 (Shevkomud, Yanshina, 2012: Fig. 52, 71). Later, in the cultures of the New Stone Age of the region, this hybrid image was further developed. The greatest (than anywhere else) number of this ceramic sculptural image was found on the Malyshevo and Voznesenovskoye dwellings at Suchu Island. A figurine of this type was also found in dwelling 1 under study. Its phallus-shaped chignon has a through hole similar to that in all such sculptures in the Amur region.

My ideas concerning the origins and purpose of Neolithic sculptural images, mainly anthropomorphic and hybrid (bisexual), of the Lower Amur region, as well as about the traditional sculpture (dogu) of the Jomon of Japan have been published in my previous papers. Here, I just want to comment on some of the conclusions reached by researchers relatively recently on the basis of my materials (see (Solovyev, Solovyeva, 2011)). A prominent place is given by the authors of the publication to the proof of the possible “dressing” of the Amur ceramic sculptures in clothes, i.e. using them as a kind of mannequins. While correctly noting the absence of limbs and tattoos in all sculptural images, the researchers point out that all of them allegedly have a through vertical hole in the body (Ibid.: 56–57). Most of the Amur figurines with phallic bodies do not have such holes (see (Medvedev, 2000: 61, fig. 6, 2, 3; 2011: 9, fig. 1, 2, 3; p. 10, fig. 2, 1, 2)). Therefore, it is needless to speculate about any “stick” stuck into the figurine from below to fix it “on a horizontal surface” (Solovyev, Solovyeva, 2011: 57). Notably, many dogu have not only arms, legs, and tattoos, but also various hairstyles, while the Amur sculptures show only one hairdo—a phallic chignon. As an argument in favor of “dressing” the sculptures, the authors cite, for example, clay people figurines found in closed underground chambers of Han China, whose articular cavities on their shoulders to secure flexible arms indicate that they wore clothes (Ibid.: 59). Amur figurines do not have such cavities. It should be added that anthropomorphic figures with phallic bodies without limbs in the Lower Amur Neolithic are typical not only of portable art, but also of petroglyphs (see, e.g., (Okladnikov, 1971: 209, pl. 73, 1)). This fact suggests deep original artistic and religious traditions in the population of this region. Academician A.P. Okladnikov, who studied primitive art for a long time, noted: “Everyone who has come into contact with the art of the Lower Amur has been impressed by its creators’ vivid originality and inexhaustible wealth of imagination. <…> The evidence of archaeology and ethnography shows the wealth and originality of the art of the Amur tribes over an enormous period of time” (Okladnikov, 1981: 10–11).

We can hardly agree with the opinion of the authors of the publication regarding the use of the through holes in the heads of the sculptures intended for fixing a “headdress or a false hairdo with a thorn” (Solovyev, Solovyeva, 2011: 58). First, the holes were made not only in the parietal part of the head, but also far below, at the level of the nose or mouth (Medvedev, 2000: 62, fig. 6, 1 ). Second, the thorn does not need a through well-designed hole.

It is hardly necessary to discuss here the essence of comparisons of the Amur sculptures with anthropomorphic ceramic figurines of the Lidovka culture of the Bronze–Early Iron Age of Primorye. This topic was considered in detail by V.I. Dyakov. He noted some of the stylistic similarities and differences of regional, cultural, and chronological order between them. At the same time, the author rightly noted that there are no figurines similar to those of Lidovka in the collections of either of the other cultures of Primorye or Amur (Dyakov, 1989: 163–165). The stylized anthropomorphic (female) figurines from the Bronze Age Sopohang settlement in North Korea are the closer parallels. The Sopohang artifacts, like the Lidovka figurines, show some fundamental distinctions from the Amur sculptures. Their bodies are not phallic in shape, but are widened at the bottom and ended with a stand. There are no through holes in them. The turned up heads of the sculptures show some holes or depressions, which have been defined as eyes or ears; the faces are flat, not detailed, “a longitudinal groovedepression has been traced” in one case (Larichev, 1978: 58, fig. 36, 9 ; p. 61; p. 68, fig. 41, 2 ; p. 75, fig. 45, 6 ) (the heads of the Lidovka figurines are trough-shaped (Dyakov, 1989: 163)).

Despite the brevity of the presented description of the figurines from Primorye and the DPRK, it is clear that neither the Sopohang nor the Amur figurines were used as mannequins. In any case, no sticks or rods were inserted into them from below; no thorns were used to secure a headdress or false hairdo on their heads. However, there is reason to believe that the tradition of manufacture of and worshipping female round sculptures endowed with magical properties, which embodied the cult of fertility in its broadest sense, which was established in the early stages of the Neolithic in the Lower Amur region, survived in its basic features in the Early Bronze Age cultures in more southerly regions, although later this tradition definitely transformed.

Conclusions

At present, there is no doubt that the artistic and cult traditions of the Lower Amur Neolithic populations occupy a special place in the primitive art of Northern Eurasia. These early original traditions were expressed in various forms and versions, primarily in round three-dimensional sculptures and in religious and mythological petroglyphic images of the region. The identification of archaic polyeiconic and polysemantic art at the earliest stages of the Neolithic in the Lower Amur has become exceptionally important (for more details, see (Medvedev, 2001)). Noteworthy are the findings of studies of the Neolithic cultures of neighboring regions—the Middle Amur and Primorye. The Middle Amur region has currently yielded a rather modest number of pieces of art and cult; almost no parallels have been established with the Lower Amur. In Primorye, the main objects of art were representatives of the aquatic fauna, although flat sculptures of terrestrial animals and humans (stone, bone) were also found (Brodyansky, 2012). The advanced level of development of the material and spiritual spheres noticeably distinguishes the people of the Osipovka culture on the Lower Amur (12th–9th millennium BC) from their close and distant contemporaries, which makes it possible to consider the Osipovka tribes as the creators of the “fishing proto-civilization”.

Although dwelling 1 at Suchu Island belongs to the Malyshevo culture, which is much younger than the Osipovka culture (late 5th to early 4th millennium BC), the figurines from the sanctuary clearly show the surviving ancient (Osipovka) style of rendering anthropozoomorphic images: three-dimensionality, polysemanticity, and bisexuality of phallic representations. The excavation yielded by no means all the artifacts that might have been stored in the dwelling when it was inhabited. But even the available items carry important information, some of which was previously unknown. First of all, this concerns the unique ceramic “necklace”. It belonged most likely to the performer of religious ceremonies and the keeper of a sacred place—a sanctuary in a dwelling. It could be a shaman-sorcerer, as indicated by other cult and ceremonial items found—labrets and a small jug. According to ethnological data, labrets were attached to decorative masks during religious rites among some peoples of the Pacific North. The performer of rituals in dwelling 1 (sanctuary), in addition to the “necklace” around his neck (it is also possible that it was attached to clothes or a belt), could have worn a bark or wooden mask with stone labrets on his face. He likely also owned the miniature jug without traces of everyday use, intended for a stimulating or intoxicating drink, which was drunk by the performer of ritual actions.

An important religious and mythological function in the dwelling must have been assigned to a ceramic sculptural image of a woman, which, together with the “necklace”, was placed in a secluded small hole in the sanctuary. Apparently, the sculpture was kept in the dwelling for a long time, possibly from the time of its construction. Obviously, the figurine personified a progenitress bringing wealth.

Acknowledgements

The study was carried out under the project “Diversity and Continuity in the Development of Cultures in the Stone Age, Bronze Age and the Medieval Period in the Far Eastern and Pacific Regions of Eurasia” (FWZG-2022-0004).

Список литературы Ceramic “necklace”: a Neolithic ritual artifact from the Lower Amur

- Brodyansky D.L. 2012 Vodnaya fauna v drevnem iskusstve Primorya. In Arkheologo-etnograficheskiye issledovaniya Severnoy Yevrazii: Ot artefaktov k prochteniyu proshlogo. Tomsk: Agraf- Press, pp. 75-77.

- Derevianko A.P., Medvedev V.E. 1995 Issledovaniye poseleniya Gasya: Predvaritelniye rezultaty, 1989-1990 gg. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Derevianko A.P., Medvedev V.E. 2002 K tridtsatiletiyu nachala statsionarnykh issledovaniy na ostrove Suchu (nekotoriye itogi). In Istoriya i kultura Vostoka Azii: Materialy Mezhdunarodnoy nauchnoy konferentsii, posvyashchennoy 70-letiyu so dnya rozhdeniya V.E. Laricheva (Novosibirsk, 9-11 dek. 2002 g.), vol. 2. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 53-66.

- Dyakov V.I. 1989 Primorye v epokhu bronzy. Vladivostok: Izd. Dalnevost. Gos. Univ.

- Larichev V.E. 1978 Neolit i bronzoviy vek Korei. In Sibir, Tsentralnaya i Vostochnaya Aziya v drevnosti: Neolit i epokha metalla. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 9-87.

- Medvedev V.E. 2000 New motifs of the Lower-Amur Neolithic art and associated ideas of the ancient people. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 3: 56–69.

- Medvedev V.E. 2001 Sources of some sculptural and rock images in prehistoric art of the southern Far East and the fi nds of the Osipovka Culture on the Amur River. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 4: 77–94.

- Medvedev V.E. 2002 Amurskiye churingi. Gumanitarniye nauki v Sibiri, No. 3: 11–15.

- Medvedev V.E. 2005 Neolithic cult centers in the Amur River valley. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 4: 40–69.

- Medvedev V.E. 2011 Skulpturniye izobrazheniya s ostrova Suchu. In Drevnosti po obe storony Velikogo okeana: K 70-letiyu vydayushchegosya Mastera dalnevostochnoy arkheologii V.E. Medvedeva. Vladivostok: Izd. Dalnevost. Federal. Univ., pp. 8–15. (Tikhookeanskaya arkheologiya; iss. 21).

- Medvedev V.E., Filatova I.V. 2020 A multidisciplinary study of fi nds from Suchu Island (1973 season, excavation II, dwelling 1). Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 48 (2): 3–13.

- Okladnikov A.P. 1971 Petroglify nizhnego Amura. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Okladnikov A. 1981 Ancient Art of the Amur Region. Leningrad: Aurora.

- Okladnikov A.P., Medvedev V.E., Filatova I.V. 2015 The first systematic excavations on Suchu Island and radiocarbon dates of the site (1972). Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 43 (3): 50–63.

- Shevkomud I.Y., Yanshina O.V. 2012 Nachalo neolita v Priamurye: Poseleniye Goncharka-1. St. Petersburg: MAE RAN.

- Solovyev A.I., Solovyeva E.A. 2011 Dogu v ritualnoy praktike epokhi dzyomona. In Gorizonty tikhookeanskoy arkheologii. Vladivostok: Izd. Dalnevostoch. Federal. Univ., pp. 47–77.