Children's games in the sociocultural space of a Siberian town: historical and archaeological context

Автор: Chernaya M.P., Tataurov S.F.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145434

IDR: 145145434 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.2.084-092

Текст обзорной статьи Children's games in the sociocultural space of a Siberian town: historical and archaeological context

The sociocultural space of urban complexes is marked by a great number of manifestations of objects, and is richly represented by archaeological evidence. Playing is one of the aspects of society’s everyday life. It is a specific activity in the area where a person is free from the necessity imposed by society and the state, yet this activity is not isolated from utilitarian aspects, and their interaction and interpenetration is determined by the specific cultural and social context (Khrenov, 2005: 17, 34).

Children’s games are a special way to generalize and systematize their ideas concerning the world around them. Games provide an active form of organizing children’s space in the world of adults, following its model. “Childhood games represent hot, tireless, but at the same time fun work helping the child to vigorously develop his spirit and body, implant knowledge and experience, and lay the first foundations for future activity in life” (Pokrovsky, 1895). Games play the role of a modeling semantic system, which helps children to navigate in the “worldly sea” in an informal manner. Game behavior

serves as a prototype of “adult” life, and symbolic gaming counterparts serve as tools for acquiring knowledge and skills. By mastering the world around them, children (individually and in company) “objectify” themselves, materialize their presence in certain more or less permanent or temporary places for playing in the house, courtyard, or outside of those, but within the borders of the territory which they master, as well as through substitute objects—toys, crafts, or drawings, which help them to assert themselves in the space of the house, and “populate with themselves” their home world (Osorina, 2000: 37).

Children’s presence in the space of house – homestead – town is manifested in the archaeological context by game attributes attached to specific objects where children used to play. A series of toys have been found in the cultural layers of towns from the time of Old Rus to Modern Russia. Various classifications of them according to their composition and material have been proposed. Excavations of Russian sites in Siberia have enriched the archaeological collection of attributes of children’s games and have significantly expanded the geographical boundaries of traditional children’s game culture, which is now equipped with a wide spatial and chronological comparative field. We will present not a very large, but diverse collection of toys from medieval Tara. In the description of the collection, the emphasis will be placed on the location of toys in the home world of the homestead and adjacent territory, which determined the role of children’s games in urban sociocultural space.

Children’s games in the homestead and urban space of Tara

The evidence from the excavations of a homestead complex in the historical center of Tara makes it possible to analyze mastering of urban space by children at the level of micro-planigraphy. Such an approach has informational advantage, since the worlds of adults and children coexist in a most natural way precisely in the living space of a homestead. Development of a child’s self-awareness and his/her socialization, including socialization by means of games, happens through interaction of these worlds.

This homestead functioned for a long time (the cultural layer was over 3 m thick), and was rebuilt several times after fires. A reconstruction at one of the stages of its operation was made on the basis of excavation results (Fig. 1). The homestead included five structures: the owner’s house—a five-wall building with extensive entry room, a log house with large stove, a cellar with a structure over it, a banya, and a well. The land plot of the homestead was rectangular in plan view and was enclosed by a fence or palisade (Tataurov, Chernaya, 2015).

Most of the toys were found in the entry room of the owner’s house (weapon models, balls, sled runner), in its residential part (children’s ceramic dishes, bird whistles, birch-bark balls), and in the courtyard—at the mound of earth around the outer walls of the log house (a set of knucklebones) (Fig. 1). Their locations are associated with the places where children could spend their free time and/ or keep their treasures thus denoting, objectifying, and consolidating their presence. Judging by the availability of toys, adult residents allowed children’s games in the house and courtyard in order to control the whereabouts of children, especially in the case of danger, which was important in the semi-military town of Tara.

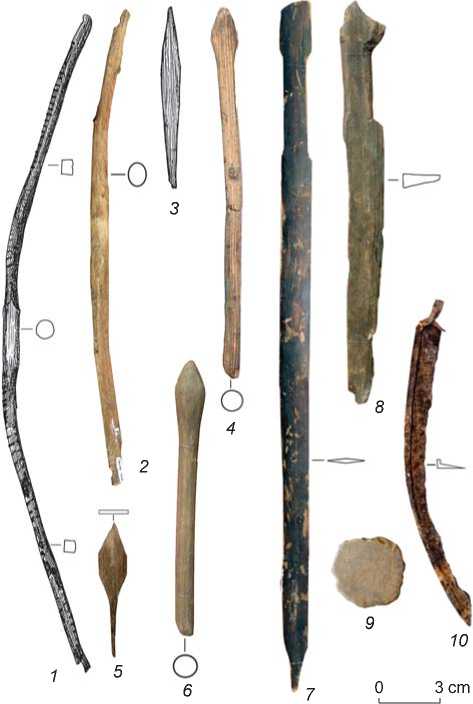

In the entry room, the boys kept their “arsenal”: two bows with arrows and two swords/sabers (Fig. 2, 1–8 ). The Tara toys imitated adult weaponry. Fathers, grandfathers, and boys cut out knives and sabers according to real military models, elaborating the most significant details—handle, guard, blade, etc. Children’s bows (five of them have been found in Tara) also show the signs of a real weapon, including widening

аb

Fig. 1. Reconstruction of a homestead with the places that children played games ( a ) and stored toys ( b ).

Fig. 2 . Toys.

1 , 2 – bows; 3 , 5 – arrowheads; 4 , 6 – arrows; 7 , 8 – swords/sabers; 9 – playing chip; 10 – scythe. 1–8 – wood; 9 – ceramics; 10 – iron.

in the central part (handle), end plates, and notches for fastening the bowstring. Toy arrows with arrowheads of various types: long narrow armor-piercing, leaf-shaped, and blunt points (Fig. 2, 3–6 ) give us some idea of the set of arrows in the quiver of a Tara archer. Children’s copies made of hazel wood, juniper, and oak from 50 to 90 cm long, with well-elaborated details, including those imitating a composite bow, glued together from pieces of wood and bone plates, are known from archaeological collections of the 9th–16th centuries from Novgorod, Pskov, Staraya Ladoga, Beloozero, Staraya Russa, etc. Toy bows after the 16th century have almost never been found in Old Russian towns, which can be explained by the disuse of this weapon. The fragments of children’s bows from the layers of the first half of the 17th century of the excavations in Pskov are attributed to the final stage of the existence of such toys (Rosenfeldt, 1997: 115; Khoroshev, 1998; Zakurina, Salmin, Salmina, 2009). In Siberia, bows remained in use as a combat and hunting weapon long after that, which is also reflected in the distribution of toy models of bows found in Tara,

Mangazeya, and at the Berezovo and Staroturukhansk fortified settlements (Parkhimovich, 2014: 256, 259, 260; Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2017: 91, 99, 174).

Wooden models of swords or sabers (one intact and one broken) have been found in the entry room of the Tara house. The identification of the type of weapon is conventional. The blade of the intact item is long and straight, and the blade of the broken weapon shows some kind of bend, but one cannot say with certainty that it was made originally in this way (Fig. 2, 8 ). A children’s weapon from Mangazeya, which was called a sword, has a straight blade (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2017: Fig. 121, 16 ; 257, 4 ). A broken Tara sword is very similar to the Mangazeya find (Ibid.: Fig. 257, 4 ) in the form of the handle, although sabers of rods with a looplike guard are also known from Mangazeya (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2008: Fig. 166, 4 ). Local children were familiar with sabers, which were a part of the weaponry belonging to the servicemen of Siberia. Children also were acquainted with swords, as indicated by the presence of a sword handle with round pommel in Mangazeya (Ibid.: Fig. 166, 5 ) (swords with similar pommels have been found in Novgorod and Sarapul (Khoroshev, 1998: Fig. 1, 3; Sarapulskaya kladovaya…, 2018: 32)).

Toy weapons from the Siberian collections confirm the conclusion made on the basis of excavations in Old Russian towns: toy-imitations present rich informative evidence for the study of weapons. The remains of pommels of wooden swords from Novgorod accurately reproduce the main proportions of real combat swords. A series of children’s swords from clearly dated stratigraphic layers have made it possible to identify evolutionary changes in military weaponry of medieval Novgorod. This is all the more valuable because iron swords have been found very rarely in the urban cultural strata (Morozova, 1990: 70; Khoroshev, 1998).

Toy weapons could have been very similar to the real prototypes. For example, the “weapon set” (wooden belt (combat) knives and a pernach (flanged “six-feathered” mace)) from a Pskov courtyard of the second half of the 17th century even causes doubts that it belonged to children, making it possible to correlate these models with the adult cultural environment as attributes of ritual or theatrical performances (Salmin, 2013). However, the main part of imitations was intended for children’s games, representing copies of real objects reduced in size. For instance, the models of bladed weapons from Tara, while reproducing the proportions of the prototypes, fit in size (50–60 cm) to a child’s height.

There are very few toy utensils, tools, shoes, or means of transportation among the Tara materials (a spatula, dishes, sled runner) as compared to other towns (Rosenfeldt, 1997: 118, 119; Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2008: Fig. 166, 167; 2017: 91, 137, 147, 165, 174, 185–186), but they also demonstrate similarity with their everyday life prototypes. Models of boats have not yet been found in Tara, but the archaeological collection of children’s boats from Novgorod gives us some idea of the level of shipbuilding, and similar finds from Mangazeya provide information on various types of ships (Morozova, 1990: 70; Khoroshev, 1998; Parkhimovich, 2014: 255). Toy-imitations serve children as “building materials” for creating their own world. Imitation is a mechanism for exploring the surrounding reality and directing children to the adult world with the available examples of things and methods of their use, even if their adult meaning is not completely understood by the children, and they reproduce it in their own way.

Two hard balls (shary) carved from tree roots have been found in the entry room of the Tara house (Fig. 3, 3, 4). A. Tereshchenko considered ball games to be “male” in nature (1848: 50–53, 58, 59). Therefore, it was logical to find these toys, along with the “military arsenal”, in the entry room where the boys kept things for their amusement. Wooden hard balls (shary) and leather soft balls (myachi) as universal toys for competitive (active) games were common in Russian towns. As a matter of fact, a ball element of segmented shape (5.0 × 8.5 cm) was found in Tara. Balls made of segments, as was the case with Tara, or from two circles and a connecting band, as was the case in Veliky Novgorod, were cut out of wet, sometimes multicolored, leather (fabric balls have been found in the excavations in Mangazeya). They were stuffed with wool, horsehair, moss, wool threads, or tow. After drying, the leather would wrap tightly around the padding. The manufacturing of leather balls was an auxiliary production in shoemaking craftsmanship. It is not surprising that those who liked playing ball games acquired balls for not a cheap price, paying several pairs of knucklebones, a good hopscotch marker, or svaika (iron pin). Lathed wooden balls, which have also been found in the cultural layers of Old Russian towns, were more expensive than hand-carved.

Different variations of games with hard or soft balls required agility, skill, and dexterity. One of the varieties involved digging a rather large pit called a kaslo or cauldron, and small holes around it according to the number of players. The game leader tried to capture someone’s place by driving a hard ball into their hole; the other players had to beat the ball away while it was approaching (Pokrovsky, 1895; Tereshchenko, 1848; Morozova, 1990: 70; Rosenfeldt, 1997: 116; Rybina, 2006: 18; Veksler, Osipov, 2000: 155; Parkhimovich, 2014: 258, 259; Osipov et al., 2017: 117, 118). This version of a ball game representing an enemy’s raid on peaceful dwellings was an imitation of real enemy attacks, town sieges, and their defense by the town dwellers. The game not only developed agility, but also cultivated combat fervor and patriotic spirit in the younger generation.

A glazed ceramic bird whistle was found in the residential part of the owner’s house at the Tara homestead (Fig. 3, 2 ). Such items, appearing in different morphological and technical variations, are a typical attribute of folk musical culture, and have often been found in settlement complexes (Fekhner, 1949: 55; Rosenfeldt, 1997: 118; Khoroshev, 1998; Kolyzin, 1998: 117; Tkachenko, Fedorova, 1998: 345, 346; Glinyaniye igrushki…, 2002; Spiridonova, 2002: 216; Matveev et al., 2008: 126, 127; Tataurova, 2008: 200; Vorobiev-Isaev, 2014; Parkhimovich, 2014: 258; Tropin, 2017: 480; Baranov, Kupriyanov, 2017: 509, 510; and others). The technology of their manufacturing is described in the ethnographic literature (Tseretelli, 1933: 183; Galuza, 1998: 172; Bondar, 2006; Korotkova, 2006). Comparison shows that despite centuries of a well-established manufacturing tradition, whistles had specific local features in terms of techniques and shapes, and

10 0 3 cm 12

Fig. 3 . Game accessories.

1–2 – bird whistles; 3–5 – balls; 6–8 – dishware; 9 – spatula; 10 – sled runner; 11 – playing chip; 12 – fragment of a composite belt. 1 , 2 , 6–8 , 11 – ceramics; 3 , 4 , 9 , 10 – wood; 5 , 12 – birch-bark.

individual artisans had their own secrets and style. Special skill was needed to make the toy perform the function of a musical instrument. The mouthpiece with a slit-like hole for blowing air was usually located in the tail of the “bird”. A part for producing the sound ( pishchik ) was located under the tail or on the back of the figurine (the toy would not whistle without it); two finger holes were on the sides. By closing the holes, the player could change the pitch and play a simple melody. Success in making the whistle was ensured by having a clear idea of the nature of sound due to the pulsation of air entering from the zone of normal pressure into the air stream, where it is lowered. The correct direction of the wind duct, free from any clay particles, was important, making the sound clear and loud (Glinyaniye igrushki…, 2002: 7; Bondar, 2006). Whistles and rattles were not only toys, but also amulets: it was believed that they scared away evil spirits from the child by their noise and whistling. This also explains their persistent use (Glinyaniye igrushki…, 2002: 8).

Girls played in the residential part of the Tara house, where miniature ceramic dishes (Fig. 3, 6–8 ), a wooden spatula (Fig. 3, 9 ), and balls made of birch-bark bands have been found. Small balls (4–5 cm in diameter) could have served as heads of dolls (Fig. 3, 5 ), and a large ball (15 cm) could have been used for playing ball games. Girls, who were attached to home, their mothers, and grandmothers, imitated important components of the adult life scenario in role games: they “cooked”, took care of the “child” by swaddling and dressing their dolls, “spun” wool, etc. Professional potters produced a significant part of toy dishware, and adults made dolls of clay, wood, straw, and rags (Fekhner, 1949: 56; Rosenfeldt, 1997: 116, 118; Kolyzin, 1998: 119; Tataurova, 2008: 199; Parkhimovich, 2014: 254, 255; and others), which manifests the interaction of children and adults in the process of training girls for the crucial role of housewife and mother. Girls also participated in active games. For example, they played ball; sometimes together with boys. Collective games are typical for children of all ages (Zabylin, 2003: 526, 531, 532).

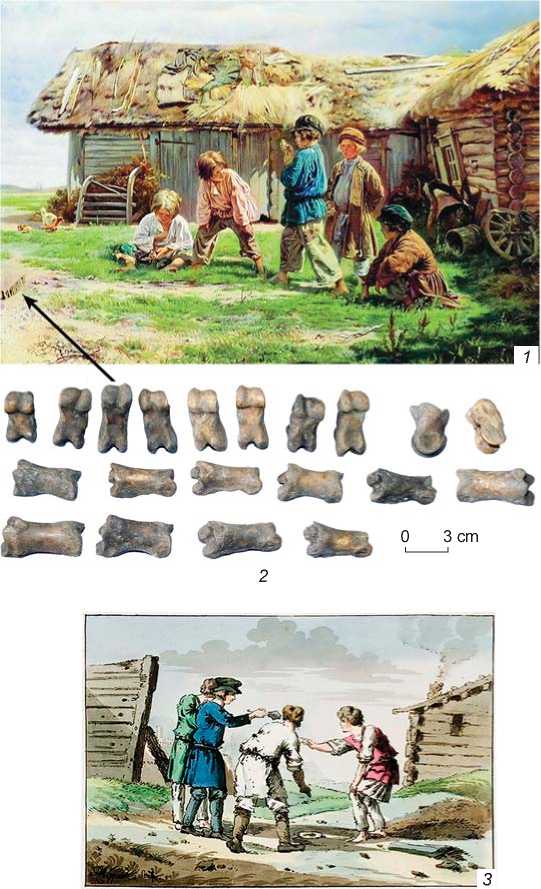

The third place for storing game attributes was found in the courtyard near the earthen mound around the outer wall of the log house. A set of 20 knucklebones (in Russia played like marbles – translator’s note ) of the same size were found in a hole about 40 cm deep, covered with a piece of birch-bark; protruding parts of joints were cut off or sawn off on some of them (Fig. 4, 2 ). The damage done to the bones shows that they were used for playing for quite a while. There was no shooter in the set (a knucklebone drilled and filled with lead), although many such finds are known. The knucklebones were stored in an area free from buildings, which implies participation of children from several homesteads in the game (Fig. 1). Boys are playing in a similar area in the picture of the famous Russian artist V.E. Makovsky (Fig. 4, 1 ).

The game of knucklebones was one of the most popular games, and this is why knucklebones have been found almost everywhere, and in Siberia both at the sites of the Russian and indigenous population, among the set of items that reached the indigenous people from/ through the Russians (Belov, Ovsyannikov, Starkov, 1981: 43; Tataurova, 2008: 198; Chernaya, 2015: 170, 171; Baranov, Kupriyanov, 2017: 504, 510). The popularity of the game was ensured by easy availability of raw materials—a hock bone, which was boiled. Knucklebones had value; they were exchanged for, for example, balls or lasy —balls of snow drenched in water and frozen (Tereshchenko, 1848: 25–26).

Certainly, it is important that the Tara set of knucklebones was hidden. Making stashes has utilitarian and symbolic aspects in children’s territorial behavior. In this way children can materialize their secret presence in a certain place and establish deep personal contact with the living space by performing secret material exchange with the environment. The arrangement of stashes/“secrets” is a tradition of children’s subculture, one of the symbolic ways of taking over the mastered territory through “growing into the soil” and being literally inside the flesh of the earth. Children’s hiding places, albeit they have been rarely found in excavations (one example is a stash with bird whistles from the Tomsk Region), are indicators of firm mastering of space and settling in the environment (Osorina, 2000: 127–145; Parkhimovich, 2004; Vorobiev-Isaev, 2014: 229; Chernaya, 2015: 36, 37; 2016: 17; Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2017: 333–340). It was important for the Tara boy who owned the stash with knucklebones to feel that he possessed his own secret, inaccessible to the uninitiated, in the space of the homestead.

During the excavation of the Tara homestead, it was possible to establish three main places where the toys were located. Yet, attributes of children’s games, such as round chips 3–5 cm in diameter made of pottery fragments (Fig. 2, 9 ; 3, 11 ), have also been found without links to specific places. Such scattered pieces have also been discovered in the fortified part of Tara. They occur at urban and rural sites in the European part of Russia and in Siberia. Such chips were used as “money” in the games of kremeshki , checkers, or “buying-selling”. “Kreymeshki are made of broken pottery and tiles; they are made round to the size of a two-kopeck piece, but no larger than a five-kopeck coin” (Tereshchenko, 1848: 42). The easy availability of such toys made of broken pottery determined the universality of their existence (Kostyleva, Utkin, 2008: 216–218; Tataurova, 2008: 198).

Individual fragments of glass vessels of European manufacture, made in the technique of onlaid glass threads, have been found on the territory of the Tara homestead. The broken vessel lost its status as a prestigious item from the adult world, but the brightly colored fragments became a real treasure for children,

0 3 cm

0 3 cm

Fig. 4 . The games of knucklebones, svaika , and mumblety-peg, and the corresponding game accessories from the Tara collection.

1 – V.E. Makovsky. “Babki game” ; 2 – set for playing knucklebones; 3 – J. Atkinson. “Svaika Game” (after (Atkinson, Walker, 1803)); 4 – svaika; 5 – knife.

who must have endowed them with new meaning, and included them into the circle of their own experiences, fantasies, interests, and relationships (Osorina, 2000: 98, 138, 139). Precious glass-pieces became not only the objects of bargaining and exchange, but, stimulating imagination, helped children to create their own world, constructed by the child-creator from broken pieces of adult things. Noteworthy is the aesthetic component introduced by girls into the game. They examine, lay out, and cherish fragments that fascinate them with their beauty and uniqueness, and try to decorate dolls or themselves. A fragment of a composite birch-bark strap found on the territory of the homestead may have also belonged to the available “designer” means for the girls of that time (see Fig. 3, 12 ).

The location pattern of children’s games based on the excavated homestead can be extended to the town as a whole, since homesteads were the main habitation type. Children played in the houses, in the backyards, and on pasture lands. It was difficult to find other areas for playing because of the density of buildings, small width of streets and mud on them, in which horse teams would get stuck even in the early 20th century (Tarskaya mozaika…, 1994: 22). Children could play outside of fortification walls only under the supervision of adults when they went to do concrete jobs.

Space constraints limited locations for team games. The space between the homesteads could have served this purpose. Svaika was one of the truly popular team games both among adult men and teenagers. A svaika— a sharpened iron pin with a massive head (length 18.7 cm, stem diameter 0.8 cm, 12-faceted head with each facet being 2 cm wide), has been found in the fortified part of Tara (Fig. 4, 4). The essence of the game was to throw the svaika into a ring or several rings lying on the ground. Foreigners also noticed fascination with this game, “Boys play with sharpened pieces of iron, trying to throw them into a ring lying on the ground” (Reitenfels, 1905: 149). J. Atkinson left a drawing (Fig. 4, 3) and a detailed description, “This is a game of dexterity peculiar to the Russians. A small iron ring of about an inch and a half in diameter is laid upon the ground, and thrown at with a heavy iron pin, with a large round knob at the top of it cut into octagon facets like a diamond. The player lays hold of the pin or svaika, by the point, and throws it in such a manner, that in whirling round the point sticks in the earth in the middle of the ring. If he misses, he is obliged to hand round the svaika to the rest of the players, till another misses and relieves him in his turn” (Atkinson, Walker, 1803).

A svaika was also a cold throwing weapon capable of penetrating the strongest armor. Sometimes it “weighs up to 4 and 5 pounds… some claim that they may weight up to half a pood…” (Tereshchenko, 1848: 54). The methods of throwing the svaikas in the game and in battle were the same; teenagers could master them together with their parents—the servicemen. People loved traditional games. Semi-sport, semi-military games (wrestling, running, horse riding, archery, tug of war with a stick or rope) raised courage, endurance, and dexterity in young people (Leontiev, 1977: 64, 65).

Miniature (about 11 cm long) knives have been repeatedly found in Tara (Fig. 4, 5 ). They were intended for sharpening goose feathers and were also used for games by teenagers. The game “mumblety-peg” was a later development, a specialized version of the svaika game. It belongs to an extensive class of competitive games “with a thing” (knucklebones, chizh , games with soft balls ( myachi ) and hard balls ( shary ), lapta , svaika , dice ( kosti ), jacks ( kameshki ), pick-up sticks ( biryulki ), peregon , etc.) (Toporov, 1998: 251, 252, 269, 270). The mumblety-peg game had a long history from among Russian games and helped young people to acquire skills of using knives both in everyday life and military service.

An interesting find is a copy of a scythe reduced in size (Fig. 2, 10 ): its length was 27 cm; width was 2 cm; the height of the strengthening rib was up to 0.4 cm. Judging by the strong wear of the blade, it was intended for acquiring the skill of working with a real scythe in a game form.

The assortment of toys was similar in the homestead of the high-status person in the center of Tara and in the fortified part. The differences were observed only in details. For instance, the runner from a sled, which was found on the homestead (Fig. 3, 10 ), was cut from a coniferous board, and had a mount for the backrest. Toy sleds from the fortified part, just like real sleds, had bent runners made of purple willow or birch. A whistle bird from the fortified part of Tara (Fig. 3, 1 ) is unglazed as opposed to the glazed whistle bird from the homestead.

The morphological and technological diversity of toys resulted from the individual style of their creators and local traditions. There was no rigid social hierarchy of toys; most of them were intended for children of different classes. Even royal children in the 17th century played both with expensive German dolls and popular toys bought at the market (Zabelin, 2014: 588).

Conclusions

The analysis of the archaeological collection of toys at the level of the layout of the homestead has made it possible to establish the places of children’s games, which were an accessible and constructive way for children to undergo socialization, adoption of their inhabited space, and to create their own microworld in it. The influence of the environment on a child through the use of toys is extremely strong, since learning about the world by people starts from random objects (stones, pine cones, sticks), and proceeds to using discarded and outdated things of the “adult world”, and further to specialized toy craftsmanship (Tseretelli, 1933: 21; Glinyaniye igrushki…, 2002: 3). Adults (parents, grandmothers, grandfathers, and toy-makers) acted as senior partners of the children, making the toys for them to play.

The game culture vividly manifests the opposition between living popular practices and spiritual instructions together with rules of a righteous life of the 16th– 17th centuries with detailed regulation of every aspect, strict requirements for everyday life, and imposition of a behavioral principle: “Our days are not the days of joy, but the days of weeping”, urging people not to laugh but to “disdain” children’s games, in which passions begin to show their destructive power already starting in adolescence, and giving instructions to raise children “with prohibitions” (Yakovleva, 2000: 10, 15, 19).

In living practice, games and toys are an essential part of everyday culture. Traditions, skills, and the art of making toys were transmitted from generation to generation within the family and at the level of toy-making craftsmanship, which is reflected in archaeological materials starting from Old Rus until the ethnographic present time. From infancy, games and toys entertained, taught, and cultivated children, helped them to grow up and explore the world around them. Through games, social and everyday concepts were embedded into the minds of children; the range of these ideas grew along with expanding the boundaries of sociocultural space inhabited by the child, going beyond the limits of the family structure and reaching the social order. Undoubtedly, the “good doctor” and teacher E.A. Pokrovsky, who wrote a wonderful book about children’s games, was right in saying, “Of course, with our game we also serve the Fatherland!” (1895).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 18-18-00487).