Chinese coins from the early medieval cemetery Gorny-10, Northern Altai

Автор: Seregin N.N., Tishin V.V., Stepanova N.F.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

We describe a representative series of Chinese coins found during the excavations at Gorny-10, carried out by expeditions from Altai State University in 2000–2003. The coins were found in eight burials (No. 6, 18, 44–46, 48, 62, 66). Because of its composition and diversity, the sample is unusual for North and Inner Asia. It includes 29 specimens, relating to various groups. Apart from coins of the Wǔ-zhū and Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo types, which are rather common outside China, there are very rare ones belonging to the Cháng-píng Wǔ-zhū and Wǔ-xíng Dà-bù categories. A numismatic analysis allowed us to date separate burials and the entire cemetery. The lower date of most burials (No. 6, 45, 46, 48, 62, 66) cannot be earlier than AD 581, as evidenced by Sui coins of the Wǔ-zhū type. Burials 18 and 41, where Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo coins were found, are later than the 630s. In view of additional data (absence of late issues of Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo coins, and results of radiocarbon analysis), burials at Gorny-10 date to late 6th and 7th centuries. Notably, coins were found only in burials of women and children. Their locations suggest that they had been used as head ornaments and parts of belt sets, as well as pendants and amulets.

Chinese coins, cemeteries, Northern Altai, Early Middle Ages, chronology, social history

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146791

IDR: 145146791 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.3.103-112

Текст научной статьи Chinese coins from the early medieval cemetery Gorny-10, Northern Altai

One of the most informative groups of imported items discovered during excavations of archaeological complexes in North and Inner Asia is Chinese coins. Such finds are rightfully considered to be an important source for clarifying the dating of objects and establishing the directions of contacts in specific periods. This article describes a collection of Chinese coins assembled during the study of burials at the Gorny-10 necropolis. The rich information capacity of this collection, unique in quantity and composition for the sites of that vast region, results from the fact that in most cases coins were found in undisturbed burials with fairly representative grave goods. This makes it possible to identify some aspects of coin use by the population living at considerable distance from the trading and artisanal centers of China, and to describe the social role of such objects and their place in the worldview of a society of the Early Middle Ages. In addition, the numismatic features became the basis for

Fig . 1. Location of the cemetery of Gorny-10.

using them as chronological markers both in analyzing individual objects and for establishing the time when the entire necropolis functioned.

Description of sources

The cemetery of Gorny-10 is located on the right bank of the Isha River, in the Krasnogorsky District of the Altai Territory (Fig. 1). In 2000–2003, expeditions from Altai State University and the “Naslediye” Research and Production Center under the leadership of M.T. Abdulganeev and N.F. Stepanova excavated 75 graves at the cemetery. The evidence from this site, which is now one of the basic referential complexes of the Early Middle Ages in the south of Western Siberia, has been described only partially (Abdulganeev, 2001; Seregin, Abdulganeev, Stepanova, 2019; Seregin, Stepanova, 2021; and others).

Coins were discovered during the excavations of eight burials at Gorny-10 (graves No. 6, 18, 44–46, 48, 62, and 66). These items were a part of grave goods in five female burials, and were also found in three children’s burials. Each grave contained from one to eight coins. The context of these items should be briefly described.

Grave 6 . Coins were found in a paired burial, on the skeleton of a 30–40-year-old female*. Seven items were located between the right elbow-joint and the spine of the deceased; one was on the right humerus.

*Anthropological identification of all evidence was made by S.S. Tur.

Grave 18 . The object had been almost completely destroyed as a result of modern economic activities. Five Chinese coins were found in the dig.

Grave 44 . Two coins were found in the burial of a 4–5-year-old child. One coin was in the place of the right knee; fragments of the second coin were found near the left elbow-joint.

Grave 45 . One Chinese coin was found on the right near the skull of a 40–55-year-old female; another coin was discovered in a rodent hole; oxides from the coin were present on the back of the skull.

Grave 46 . This object, containing the bones of a child, had been severely damaged in the course of economic activities. Two Chinese coins were found in the western part of the grave.

Grave 48 . Three coins were discovered in the burial of a child 6–7 years of age. One coin was in the area of the buried child’s belt; two coins, one of which had holes, were located in the neck area.

Grave 62 . A Chinese coin was found near the bones of the right hand in the area of the belt of a deceased female 23–25 years of age.

Grave 66 . Six Chinese coins were discovered in the burial of a female 25–35 years of age. One coin was on the facial area of the skull; two more were under the skull; the rest were found in burrows to the south of the grave.

Thus, in the cases when the excavations have revealed the initial situation (the complex had not been not disturbed), coins were most often found near the head of the deceased person (graves 45, 48, and 66), on the chest or at the neck (graves 6 and 48), or in the area of the person’s belt (graves 6, 44, 48, and 62).

The collection of coins from Gorny-10 includes 29 items belonging to various groups (see Table )*. Analysis of the coins and comparison with the available evidence has made it possible to identify these and establish the period of their manufacture.

Analysis of the evidence

Now let us turn to the detailed analysis of the coins found at the cemetery Gorny-10.

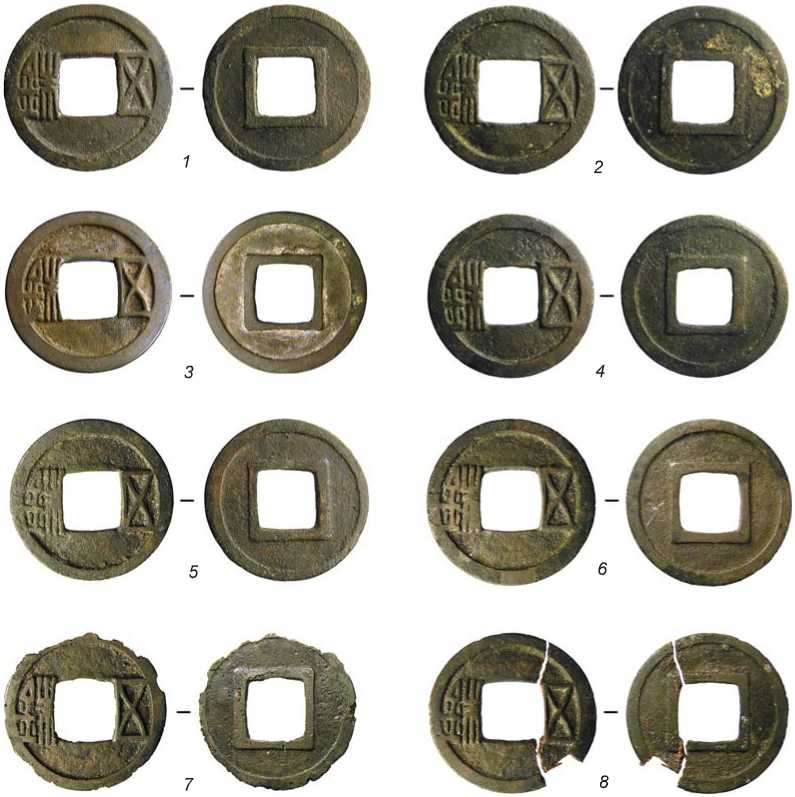

Grave 6 . All eight coins (Fig. 2) belong to the so-called Wǔ-zhū 五銖 type** of the Sui Dynasty; their

Chinese coins from graves at the Gorny-10 cemetery

78 (Western Wei), 79 (Sui); 1991a: 129, note 2, pl. VI, fig. 6, 7; Jen, 2000: 35, 36, No. 129)*. A strong argument in favor of this dating is the fact that 39 WU-zhu E# coins with the internal “bar”, straight outlines of diagonal

*In this case, according to the features mentioned by F. Thierry (the corners of character wu E expand to the outer rim of the coin; horizontal line of jin 8 element is shifted to the left in relation to the base of its top) (Thierry, 1988: 350, [fig.] A' (Western Wei); 1989: 244, No. 77), coin No. 4 from grave 6 at Gorny-10 should be dated to 546 AD, and other coins to 540 AD.

3 cm

Fig. 2. Chinese bronze coins from grave 6.

lines of the character wu E , and beveled top (“arrow”) of jin $ element of character zhu # were discovered in the tomb of Hóu Yì 侯義 of Western Wei, dated to 544 AD according to the epitaph (Thierry, 1988: 350–351, [fig.] A''; 1989: 231, 245-246, 244, No. 76). The diameter of such items was 25 mm; their weight was 3.7 g (Wáng Taichu, 1998).

A stylistically and typologically identical WW-zhu coin is known from the Timiryazevo-1 burial mound. Its diameter was 23.5 mm; its weight was 2.1 g. Considering that the weight of Western Wei coins was about 4 g and the fact that such coins, calligraphically similar to Western Wei coins, were used in the Sui period, the authors of the publication dated this item to 589–600 AD (Zaitseva et al., 2016: 294–295). They identified the coin as type 10.26 according to D. Hartill’s catalog. However, the design of the top (“arrow”) of jin $ element of character zhu # makes it possible to identify the coin as type 10.25 (Hartill, 2005: 94).

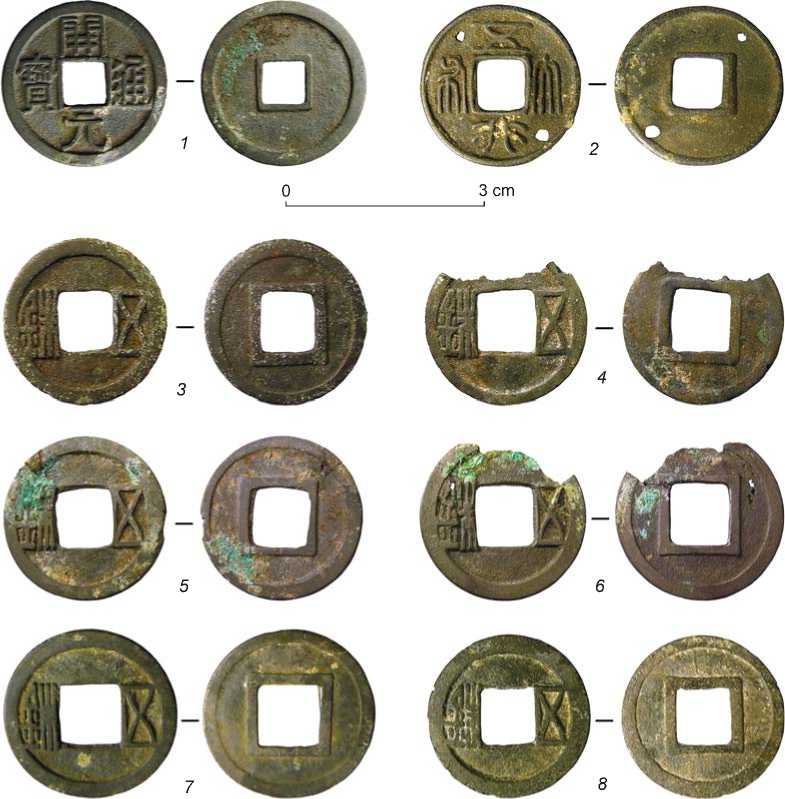

Grave 18 . This burial is distinguished by the greatest variety of coins. Chang-ping wW-zhu ^EE# coins (Fig. 3, 1 , 2 ) had been issued in Northern Qi starting from the 4th year of the reign of Tian-bao E^ era (553). They were thin and weighed about 4.2 g (Peng Xinwei, 1994: 194, 200, pl. 38, fig. 10). In the early period of the Sui Dynasty, these coins were permitted to be used along with other coins, as was stated by a special decree of 583 AD. However, already in 584 AD, the situation became more complicated, and in 585 AD the circulation of coins of old types was prohibited (Materialy…, 1980: 119).

Coin No. 3 of the WW-zhu type (Fig. 3, 3 ). The outer rim of this coin is thin; the stroke of the inscription is thick. The horizontal lines of the image of the character ww E protrude towards the central hole of the coin. In the second character zhu # , the upper part of jin $ element is depicted as an equilateral triangle (with solid filling), and halves of its base are equidistant from the middle horizontal line. Four dots in the sectors of the wáng 王

3 cm

Fig . 3. Chinese bronze coins from grave 18.

radical look like vertical lines. Side lines in the upper part of element zhu Ж are shorter than in the lower part; bends are on the same level as the base of the upper part of the jin $ element; they are only slightly rounded in its upper and well-rounded in its lower part. Neither character expands beyond the levels of the upper and lower edges of the central hole. All edges of the hole are beveled on the obverse side of the coin and are edged with a frame on the reverse side. Such features as horizontal lines of character wu 5 , protruding towards the inner hole, and angular bends in the upper part of character zhu Ж are typical of the coins cast by Liú Xuán 劉玄 , the ruler of Huai-yang Ж^ , also known as the emperor Geng-shi-di 更始帝 (23–25 AD) of Western Han, in the second year of his reign (24 AD) (Peng Xinwei, 1994: 123, pl. 37, fig. 2; Thierry, 1988: 231, 237, No. 39, p. 238). Their diameter is 25 mm; their weight is 2.7-2.8 g (Niu Qunsheng, 2001)*.

Coin No. 4 is of the WU-zhu type (Fig. 3, 4). This coin was identical to the items from grave 6**.

Coin No. 5 is of the Kai-yuan Tong-bao Ж^ЙШ type (Fig. 3, 5). It is a coin of the Tang Dynasty, introduced in 621 AD; its original weight was 2.4 zhu #, which is about 4 g (Peng Xinwei, 1994: 246-248, 262, pl. 40; Thierry, 1991b: 212–213; Hartill, 2005: 103). According to the combination of features (primarily, the slightly trapezoidal shape of character kai Ж, and the location and length of its internal vertical lines (jzng # element), which do not touch the frame of the inner hole; the average length of the first line in character yuán 元 and the shape of the bend in its right “leg”, which does not form a hook; the semicircular outlines of the upper element of character tong Й, the shape of its three dots on the left, and the small hook at the end of the horizontal base; and the rounded “feet” of character bao Ш), this find can be attributed to type I B (according to Thierry) (Thierry, 1991b: 220, No. 5–16: 221). Such coins were produced in 621–718 AD (cf.: (Hartill, 2005: 105), where other criteria are mentioned). These features of type I B make it possible to correlate the coin with the item from a tomb dated to the 21st year of the Zhen-guan Й® era following the Sui (especially grave 18, where such coins were found together with Chang-pung Wu-zhu and Kai-yuan Tong-bao coins), is an argument in favor of correlating them precisely with the Sui. Their correlation with the Western Wei would make it strange that there were no Sui coins in the burials containing the coins of Northern Qi, Northern Zhou, and Tang.

(10.02.647–29.01.648) (Jen, 2000: 300, No. 5; Thierry, 1991b: 238). Judging by the available data, such coins were minted during the reign of the emperor Tai-zong (626–649).

Grave 44 . Coin No. 1 is of the Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo type (Fig. 4, 1 ). According to the combination of features, it can be described as type I B (according to Thierry, see above).

Coin No. 2 is of the Wǔ-zhū type. The available fragments make it possible to identify the typological affiliation of the coin. According to the preserved “bar”, it can be correlated with similar items from grave 6 (closer to coin No. 4).

Grave 45 . Two Wǔ-zhū coins (Fig. 4, 3 , 4 ) are similar to the items from grave 6 (and the first one is closer to coin No. 4).

Grave 46 . Both coins (Fig. 4, 5, 6) are identical to the items from grave 6 described above.

Grave 48 . Two Wǔ-zhū coins (Fig. 4, 7 , 8 ) are similar to items from grave 6. More rare is coin No. 3 of the Wǔ-xíng Dà-bù 五行大布 type (Fig. 4, 2 ), which shows additional holes. Wǔ-xíng Dà-bù coins began to be minted in Northern Zhou in the 6th month of the 3rd year of the Jiàn-dé 建德 era (05.07–02.08.574). It is believed that their standard weight was about 4.5 g. Owing to the appearance of many counterfeit coins, circulation of Wǔ-xíng Dà-bù coins in the border provinces was already terminated in the 7th month of the 4th year of the Jiàn-dé era (23.07–21.08.575) (Peng Xinwei, 1994: 194, 200, pl. 39, fig. 2–3; Thierry, 1991a: 130, 135–136, note 18, pl. 8, fig. 25; Materialy…, 1980: 118). Thierry mentioned a coin weighing 1.75 g, which he identified as false. Since the issue of these coins was terminated in 575 AD, Thierry observed that the weights of such coins would become 61 % lighter over the course of a year (1991a: 136, pl. 8, fig. 26). In the early period of

3 cm

Fig . 4. Chinese bronze coins from graves 44 ( 1 ), 45 ( 3 , 4 ), 46 ( 5 , 6 ), 48 ( 2 , 7 , 8 ).

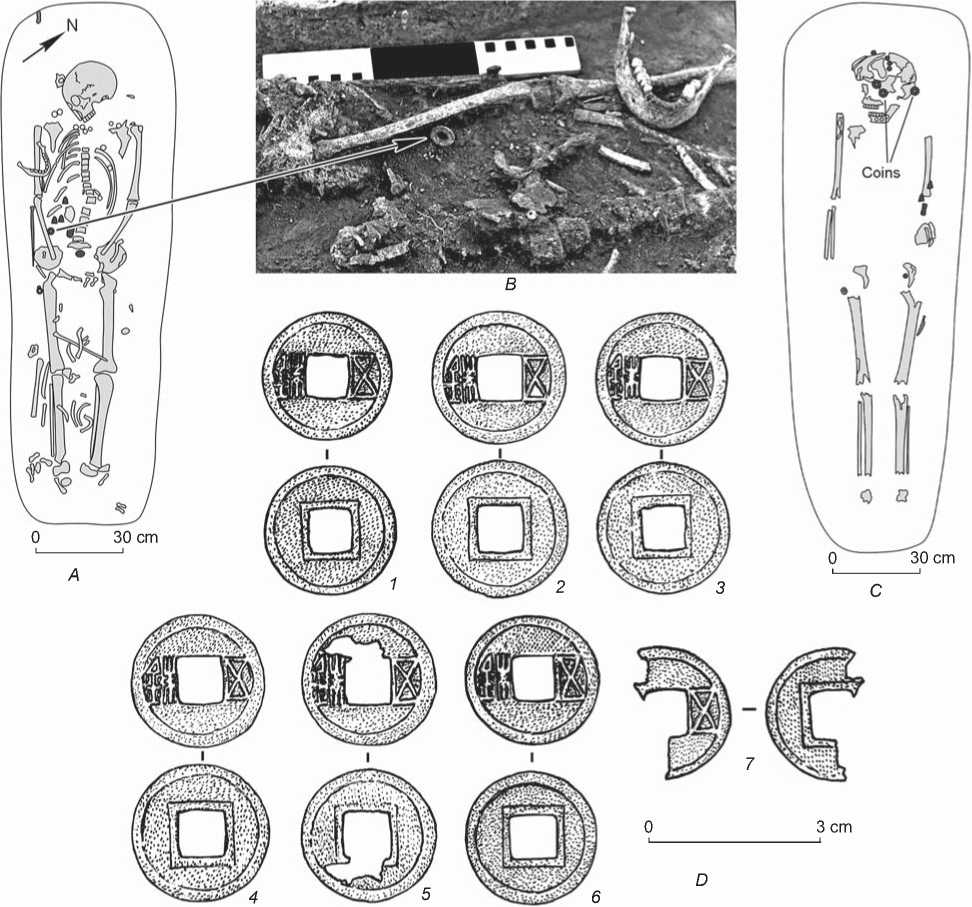

Fig . 5. Plans of burials 62 ( A ) and 66 ( C ), fragment of burial 62 ( B ), and Chinese bronze coins from these objects ( D ).

the Sui Dynasty, the use of Wǔ-xíng Dà-bù coins was allowed (decree of 583 AD), but already in 585 AD the circulation of all old coins had been officially banned (Materialy…, 1980: 119).

Grave 62 (Fig. 5, A , B ). The only numismatic find from this object was a Wǔ-zhū coin (Fig. 5, D , 1 ). It has been lost, but on the basis of its features visible on the photograph and the drawing (thick rim and internal “bar”), it can be considered similar to the coins from grave 6. Judging by the surviving evidence, the lost six coins (Fig. 5, D , 2–7 ) belonged to the same widespread group.

Grave 66 (Fig. 5, C ). Items No. 1 and 4 (Fig. 5, D , 2 , 5 ) are closer to coin No. 4 from grave 6.

Discussion

The collection of Chinese coins from burials at Gorny-10 is undoubtedly unique for archaeological sites of North and Inner Asia. First of all, the number of discovered coins is remarkable. Such finds from separate complexes occur extremely rarely at the early medieval sites in this vast region. The collection is also very diverse to include not only fairly common groups of coins ( Wǔ-zhū , Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo ), but also items that are very rare outside of China ( Cháng-píng Wǔ-zhū , Wǔ-xíng Dà-bù ).

Burials from the initial period of the Early Middle Ages in the forest-steppe Altai contained almost no

Chinese coins. At the sites belonging to the time of the Türkic Qaghanates in this region, only one such find (a Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo coin) has been discovered, at the settlement of Akutikha (Kazakov, 2014: fig. 4). A small series of coins, consisting of about ten Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo coins, was found in the later burials of the Srostki culture (Gavrilova, 1965: fig. 11, 1 ; Abdulganeev, Shamshin, 1990: 104, fig. 2, 4 ; Savinov, 1998: 179, fig. 8, 5 ; Serov, 1999: Fig. 1–4; Mogilnikov, 2002: 27, fig. 68, 1 ; Tishkin, Gorbunov, Serov, 2020). In addition, some accidental finds are known; but their interpretation is difficult owing to the lack of context.

A similar situation occurs in studying early medieval sites in the adjacent territories. Seventeen coins were found in archaeological complexes belonging to the Türks. Almost all of them were Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo ; a Wǔ-xíng Dà-bù coin was also found in one burial (Tishkin, Seregin, 2013: Pl. 1). A series of over twenty coins of different groups has been discovered during the excavation of burials in the Novosibirsk region of the Ob (Troitskaya, Novikov, 1998: 30–31; Masumoto, 2001). A little more than ten items have been found at the sites of the early medieval population of the Kuznetsk Basin (Kuznetsov, 2007: 216–217; Ilyushin, 2010).

This overview emphasizes the exclusivity of the collection of Chinese coins from the cemetery of Gorny-10. Analysis of these finds makes it possible to address several aspects in interpreting the evidence from the excavations at the necropolis. Specific numismatic features of the coins are important in clarifying the chronology of both individual objects at the site, and the entire complex. First of all, these determine the terminus post quem for specific burials. Judging by the data obtained, the lowest date for the construction of most of the objects (graves 6, 45, 46, 48, 62, and 66) cannot be earlier than 581 AD, as the discovery of the Sui Wǔ-zhū coins confirms. Taking into account the remoteness of the forest-steppe Altai from the trading and artisanal centers of China, these coins must have reached the area in the subsequent decades.

Burials in graves 18 and 44, where the Kāi-yuán Tōng-bǎo coins were found, were made no earlier than the second quarter–mid 7th century AD*. The secondary factor, which can be used in establishing the chronology of the Gorny-10 cemetery, is the absence of later issues of these coins (which became quite widespread outside of China and have most often been discovered in the sites of North and Inner Asia). This fact serves as indirect evidence that the objects of the complex were built in the 7th century AD. One should also take into account the possible long-term existence of imported metal items. A clear, albeit rather unexpected, example of this is the discovery of Wǔ-zhū coins from the early 1st century AD in grave 18.

The above observations about the chronology of the site are confirmed by the published research into the evidence from a number of objects at Gorny-10. Its time of construction has been established as within the late 6th–7th (possibly early 8th) centuries AD (Seregin, Abdulganeev, Stepanova, 2019; Seregin, Stepanova, 2020, 2021; and others). In addition, a similar picture is revealed by the first radiocarbon dating data, which will be presented in a special publication.

It is generally accepted that Chinese coins discovered at the early medieval sites of North and Inner Asia were not the means of payment, but were used as ornaments or amulets (Troitskaya, Novikov, 1998: 30; Masumoto, 2001: 52; Basova, Kuznetsov, 2005: 135; Tishkin, Seregin, 2013: 54–55; Zaitseva et al., 2016: 295–296; and others). Considering the context of individual finds, the evidence of the excavations at Gorny-10 confirms this conclusion. Judging by the available data, in a number of cases, coins, together with other elements (mainly bronze plaques, rarely beads), were a part of a complex of head ornaments (Fig. 5, C ). The discovery of single coins in the area of the chest or below the neck of the dead suggests the use of such coins as pendants or amulets. In addition, the coins under discussion might have served as elements of belt decoration (Fig. 5, A , B ).

For the population that left the Gorny-10 cemetery, coins had a pronounced sexual context. Such items were found mainly in female burials. Those children’s burials where coins were found might have also belonged to girls. Most of the graves with coins contained rich inventory indicating a fairly high status for the deceased during their lifetime—or, in the case of children’s burials, the status of their family. In the meantime, such finds were absent from a number of “elite” objects.

Owing to the fragmentary evidence, it is difficult to offer a convincing explanation for such a representative collection of Chinese coins at a single site, given the almost complete absence of such items in the contemporaneous objects of the forest-steppe Altai. Indirect contacts between the periphery of nomadic empires and China certainly existed in the initial period of the Early Middle Ages, as evidenced by the finds from the complexes of the Novosibirsk and Tomsk regions of the Ob, and Kuznetsk Basin. However, the complete absence of other items of Chinese import in the burials at Gorny-10 (metal mirrors, silk and lacquer items) is noteworthy. Further analysis of the evidence, and targeted excavations, will make it possible to clarify the complex historical fate of the population that left the sites from the time of the Türkic Qaghanates in the region.

Conclusions

The numismatic collection assembled during the excavations of burials at the Gorny-10 cemetery includes several groups of Chinese coins. The exceptional nature of this collection results both from the large number of items (29 coins) and their variety. They include both fairly common specimens, and coins very rarely found outside the Celestial Empire. Since in most cases coins were found in undisturbed burials, it is possible to make a number of observations about their use by the early medieval population of the forest-steppe Altai. Judging by the evidence, the coins were a part of the head decoration of buried women and children, could have been used as pendants or amulets, and were also a decorative element of the outfit.

Taking into account relatively rich inventory found in burials with coins in almost all cases, and the results of numismatic analysis of the finds, these objects can be considered as referential for establishing the functioning period of the site, and can be used for clarifying the chronology of the archaeological complexes of the Early Middle Ages in the forest-steppe Altai and adjacent territories. It has been established that most of the examined burials were made no earlier than the 590s AD, and two graves with Kai-yuan Tong-bao coins were made later than the 630s AD. Taking into account additional data (lack of later issues of Kai-yuan Tong-bao , first results of radiocarbon analysis), most of the objects at Gorny-10 can be dated to the late 6th– 7th centuries AD.

Further research aimed at clarifying the chronology of the known sites from the time of the Türkic Qaghanates in the forest-steppe Altai and adjacent territories seems to be very promising. It is of great importance for reconstructing the directions and dynamics of the contacts between the population inhabiting the periphery of nomadic empires and artisanal and trading centers. Thus, the almost complete absence of coins of the pre-Tang period from the archaeological sites of the Türks in Inner Asia is a strong indication that such items reached Western Siberia via other ways. Expansion of evidence, as well as comprehensive analysis of the already available data, will make it possible to clarify, at a new level, a number of aspects of the ethnic, political, and economic history of that vast region in the Early Middle Ages.

Acknowledgments

Analysis of the numismatic collection and interpretation of the described complex were supported by the Russian Science Foundation, Project No. 20-78-10037. Processing of the evidence from the excavations at the Gorny-10 cemetery was a part of the Project “Comprehensive Studies of Ancient Cultures of Siberia and Adjacent Territories: Chronology, Technologies, Adaptation, and Cultural Ties” (FWZG-2022-0006).

Список литературы Chinese coins from the early medieval cemetery Gorny-10, Northern Altai

- Abdulganeev M.T. 2001 Mogilnik Gorny-10 - pamyatnik drevnetyurkskoy epokhi v severnykh predgoryakh Altaya. In Prostranstvo kultury v arkheologo-etnograficheskom izmerenii: Zapadnaya Sibir i sopredelniye territorii. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 128-131.

- Abdulganeev M.T., Shamshin A.B. 1990 Avariyniye raskopki u s. Tochilnoye. In Okhrana i ispolzovaniye arkheologicheskikh pamyatnikov Altaya. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 99-104.

- Basova N.V., Kuznetsov N.A. 2005 Ukrasheniya i amulety iz srednevekovykh kurganov Kuznetskoy kotloviny. In Problemy istoriko-kulturnogo razvitiya drevnikh i traditsionnykh obshchestv Zapadnoy Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 134-136.

- Gavrilova A.A. 1965 Mogilnik Kudyrge kak istochnik po istorii altaiskikh plemen. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka.

- Hartill D. 2005 Cast Chinese Coins: A Historical Catalogue. Victoria: Trafford Publishing.

- Jen D. 2000 Chinese Cash Identification and Price Guide. Iola: Krause Publications.

- Ilyushin A.M. 2010 Monety v srednevekovykh drevnostyakh Kuznetskoy kotloviny. Vestnik Kuzbassskogo gosudarstvennogo tekhnicheskogo universiteta, No. 4: 185-188.

- Kazakov A.A. 2014 Odintsovskaya kultura Barnaulsko-Biyskogo Priobya. Barnaul: Izd. Barnaul. Yurid. Inst. MVD Rossii.

- Kuznetsov N.A. 2006 Monety iz pamyatnikov verkhneobskoy kultury. In Tyurkologicheskiy sbornik. Moscow: Vost. lit., pp. 212-222.

- Masumoto T. 2001 Kitaiskiye monety iz srednevekovykh pogrebeniy Zapadnoy Sibiri. In Prostranstvo kultury v arkheologo-etnografi cheskom izmerenii: Zapadnaya Sibir i sopredelniye territorii. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 49-52.

- Materialy po ekonomicheskoy istorii Kitaya v ranneye Srednevekovye (razdely “Shi kho chzhi” iz dinastiynykh istoriy). 1980 Moscow: Nauka.

- Mogilnikov V.A. 2002 Kochevniki severo-zapadnykh predgoriy Altaya v IX- XI vekakh. Moscow: Nauka

- Niú Qúnshēng. 2001 Liú Xuán Gēngshǐ wǔ-zhū qián. Qiánbì bólǎn, No. 4: 26-27. (In Chinese).

- Peng Xinwei. 1994 A Monetary History of China (Zhongguo Huobi Shi), E.H. Kaplan (trans.). Bellingham: Western Washington University. (East Asian Research Aids and Translations; vol. 5).

- Savinov D.G. 1998 Srostkinskiy mogilnik (raskopki M.N. Komarovoy v 1925 g. i S.M. Sergeeva v 1930 g.). In Drevnosti Altaya, iss. 3. GornoAltaysk: Gorno-Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 175-190.

- Seregin N.N., Abdulganeev M.T., Stepanova N.F. 2019 Pogrebeniye s dvumya loshadmi epokhi tyurkskikh kaganatov iz nekropolya Gorniy-10 (Severniy Altai). Teoriya i praktika arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy, No. 2: 15-34.

- Seregin N.N., Stepanova N.F. 2020 Rogovoye stremya iz nekropolya epokhi tyurkskikh kaganatov Gorniy-10 (Severniy Altai). In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXVI. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 603-610.

- Seregin N.N., Stepanova N.F. 2021 “Elitnoye” detskoye pogrebeniye epokhi tyurkskikh kaganatov iz Severnogo Altaya. Stratum Plus, No. 5: 335-344.

- Seregin N.N., Tishin V.V., Stepanova N.F. 2021 Hephthalite coin from an Early Medieval burial at Gorny-10. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 49 (4): 100-108.

- Serov V.V. 1999 Nakhodka drevnikh kitaiskikh monet na Altaye. In Sedmaya Vserossiyskaya numizmaticheskaya konferentsiya, Yaroslavl, 19-23 aprelya 1999 g.: Tezisy dokl. i soobshch. Moscow: pp. 47-48.

- Thierry F. 1988 Wuzhu des Sui ou wuzhu des Wei? Bulletin de la Société française de numismatique, No. 4: 349-351.

- Thierry F. 1989 La chronologie des wuzhu, étude, analyse et propositions. Revue numismatique, 6e sér., vol. 31: 223-247.

- Thierry F. 1991a La politique monétaire des Zhou du Nord (557-581): Génèse idéologique et nécessités fi nancières. Revue belge de numismatique, vol. 137: 127-140.

- Thierry F. 1991b Typologie et chronologie des kai yuan tong bao des Tang. Revue numismatique, 6e sér., vol. 33: 209-249.

- Tishkin A.A., Gorbunov V.V., Serov V.V. 2020 Kitaiskiye monety iz Biyskogo krayevedcheskogo muzeya: Istoriya izucheniya, rentgenofl yuorestsentniy analiz i datirovka. Teoriya i praktika arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy, No. 4: 189-197.

- Tishkin A.A., Seregin N.N. 2013 Kitaiskiye izdeliya iz arkheologicheskikh pamyatnikov rannesrednevekovykh tyurok Tsentralnoy Azii. Teoriya i praktika arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy, No. 1: 49-72.

- Troitskaya T.N., Novikov A.V. 1998 Verkhneobskaya kultura v Novosibirskom Priobye. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Wáng Tàichū. 1998 Yǒng-píng wǔ-zhū kǎo-biàn. Shǎnxī jīnróng, No. 9: 62-63. (In Chinese).

- Zaitseva O.V., Kuznetsov N.A., Belikova O.B., Vodyasov E.V. 2016 Zabytiye kompleksy i kitaiskiye monety Timiryazevskogo-1 kurgannogo mogilnika. Sibirskiye istoricheskiye issledovaniya, No. 4: 281-301.