Collection related to the Omaguaca Indians from the Pucara de Tilcara fortress, Northwestern Argentina, at the Museum of anthropology and ethnography RAS, St. Petersburg: tentative findings

Автор: Dmitrenko L.M., Zubova A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Anthropology and paleogenetics

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145472

IDR: 145145472 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.1.149-157

Текст обзорной статьи Collection related to the Omaguaca Indians from the Pucara de Tilcara fortress, Northwestern Argentina, at the Museum of anthropology and ethnography RAS, St. Petersburg: tentative findings

The fortified settlement of Pucará de Tilcara was located near the place of inflow of the Guesamayo River into the Río Grande River, in the Quebrada de Humahuaca valley (the Province of Jujuy, Northwestern Argentina). It was founded by the Omaguaca Indians in the 8th century AD, and ceased to exist upon arrival of Spanish conquistadors in 1536. Since 1493, it had been a fortress. By the end of the 15th century, it had been finally conquered by the Incas, under the leadership of Túpaq Yupanqui, and remained under their reign for the last 50 years. In 1586, the modern settlement of Tilcara was founded about 1 km northeast of the fortress. The Pucará de Tilcara site pertains to the Regional Development period (Seldes, Botta, 2014; Sprovieri, 2013: 26), also known as the Late Ceramic period (Handbook…, 2008: 587).

The fortress occupied 61 thous. m2 and accommodated about 2 thousand buildings, enclosed by a wall of stone slabs. Its ruins were discovered at the beginning of the 20th century by J.B. Ambrosetti. In 1908, he started systematic excavations at the site. The works were conducted till 1910 (Zaburlín, Otero,

2014: 212). During the following 100 years, the fortress territory was subjected to repeated irregular excavations. After the death of Ambrosetti, studies of the site were continued by his disciple and associate S. Debenedetti in 1918 and 1928–1929. The site became one of the classic examples of the Omaguaca Indians culture, and the foremost Argentinian archaeologists worked in its territory (Casanova, 1958–1959; Krapovickas, 1958–1959; Madrazo, 1969; Tarragó, 1992; Tarragó, Albeck, 1997; Zaburlín, 2009, 2010; Otero, Ochoa, 2011; Otero, 2013; Otero, Cremonte, 2014). In 1935, upon the initiative of archaeologist E. Casanova, a monument devoted to the memory of Pucará de Tilcara’s discoverers was erected in the northwestern part of the fortress by architect M. Noel (Casanova, 1950). It was installed in the area excavated by Ambrosetti (Zaburlín, Otero, 2014: 207), and actually covered and destroyed the cultural layer.

Despite the primary importance of the site for studying the Omaguaca culture, systematic analysis of collections obtained in 1908–1910 was not conducted earlier. In 1912, a brief note by Ambrosetti (1912) about the first excavations, and a review article by Debenedetti (1912) about the cemetery in Pucará de Tilcara were published. A small paper about clay jars from Tilcara came out shortly before the death of Ambrosetti (1917). In 1930, a monograph by Debenedetti (1930) devoted to later excavations of the fortress was released. Initially, this was intended as a consolidated scientific paper summarizing the results of study of the site from 1908 to 1929; but finally, it only tangentially addressed the early stage of the works, while the main part of the monograph was devoted to the excavations conducted by Debenedetti in 1928– 1929. The materials obtained by Ambrosetti in 1908– 1910 were never published. The museum politics of that time led to fragmentation of the collections as a result of numerous international exchanges, which precluded taking a general look at the archaeological assemblages for long years. Before long, the finds from excavations conducted by Ambrosetti were sent to the largest museums of Europe, Asia, and America, including the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in St. Petersburg.

Though more than 100 years have passed since the start of the study of the site, the research interest in its materials remains persistently high. On the Argentinian side, the works for reconstructing the site’s excavation history and studying the documentary records of its early research stage are conducted by scientists from the Tilcara Interdisciplinary Institute (the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature of the University of Buenos Aires) and the National University of Jujuy, K. Otero and M.A. Zaburlin. In 2014, they discovered handwritten notes by Ambrosetti about the 1908–1910 excavations at Pucará de Tilcara, in the archive of the Ethnographic Museum in Buenos Aires (Zaburlin, Otero, 2014). The manuscript was badly damaged; however, it preserved information about a number of studies conducted at the site, and references to several items currently stored in the MAE RAN collection. The modern favorable situation created in the sphere of international cooperation has made it possible to compare earlier separated assemblages for the purpose of their further unified scientific interpretation.

Materials

Finds from Pucará de Tilcara were delivered to MAE RAN in 1910 under the exchange project with the Ethnographic Museum in Buenos Aires (Lukin, 1965: 132). The collection was first mentioned in the letter of Ambrosetti, the Director of this museum, to MAE’s Senior Ethnographer L.Y. Sternberg of September 30, 1910, with the information that the Argentinian party is “sending antiquities found during excavations of the Pucará de Tilcara fortress in the Quebrada de Humahuaca valley” (SPbF ARAN. F. 282, Inv. 1, Item 179, fol. 390–391). The list of items sent to St. Petersburg was preserved in the archive of the Ethnographic Museum named after J.B. Ambrosetti (Archivo Fotográfico y Documental del Museo Etnográfico “Juan B. Ambrosetti”. Legajo No. 50). The inventory of the MAE collection contains one more letter from Ambrosetti, dated December 6, 1910, wherein he duplicated the information about the place of origin of the materials. This letter was accompanied by the full list of items to be transferred to MAE. According to this list, 153 archaeological artifacts and 20 deformed skulls were sent to St. Petersburg.

Discussion

Attribution of the MAE RAN collection required a great scope of research work. It involved studying the remaining museum documents together with the primary source, that is with the general catalogue of the Ambrosetti Ethnographic Museum, as well as with the items actually sent from Buenos Aires. According to the latest studies, the finds of early excavations conducted by Ambrosetti originate from the fortress area that functioned after the conquest of Pucará de Tilcara by the Incas (the end of the 15th–16th centuries).

As a result of comparing the available field ciphers with the general catalogue of the Ambrosetti Ethnographic Museum, the items that do not pertain to the Pucará de Tilcara assemblage have been distinguished. These originate from the site of La Paya, contemporaneous with the fortress, and were placed into this collection mistakenly. The items include a bronze plate (1306; 1800-130) and a large shell of the Pecten genus (1378; 1800-110) both found during excavations by the second expedition of the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature of the University of Buenos Aires in 1906; as well as an amulet made from the Azorella madreporica plant (1730; 1800-133), discovered by the third expedition in 1907.

113 items in the MAE collection have preserved their field numbers. According to the documents, these pertain to the excavations conducted by the fourth to sixth expeditions of the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature in Pucará de Tilcara in 1908–1910. These finds are subdivided into six categories: cranial sample, ceramic vessels, stone items, horn and bone items, those made of other organic materials, and copper items.

Cranial sample. The sample includes 20 skulls: 18 belonged to adults (7 female and 11 male), one to a 6–8 year old subadult, and one to 14–15 year old female. At the time the specimens were received from the Buenos Aires museum, all the skulls had mandibles. But during re-registration of the collection in 1934 by E.V. Zhirov, a member of the anthropology department, all the mandibles except one were excluded from the sample, as it was not clear if these belonged to the skulls from Pucará de Tilcara (see MAE collection description, No. 5148).

All the individuals display artificial fronto-occipital deformations (Fig. 1). Traumatic lesions were detected in some of them as well. These include at least two cases of healed vault blunt force trauma, one case of a peri-mortem blunt force trauma, a case of penetrating wound (likely the cause of death of the individual), and a case of nasal bone fracture. Such a high frequency of traumatic lesions is typical of the Omaguaca Indians during the Regional Development period.

The most abundant types of pathological manifestations in the sample are related to dental health. Most individuals exhibit multiple cases of antemortem tooth loss, alveolar abscesses, dental chipping, periodontal disease, caries, and dental calculus. The only mandible displays signs of a surgical operation aimed at extracting a lower molar and treating an alveolar abscess. The intervention was likely carried out shortly before the individual died.

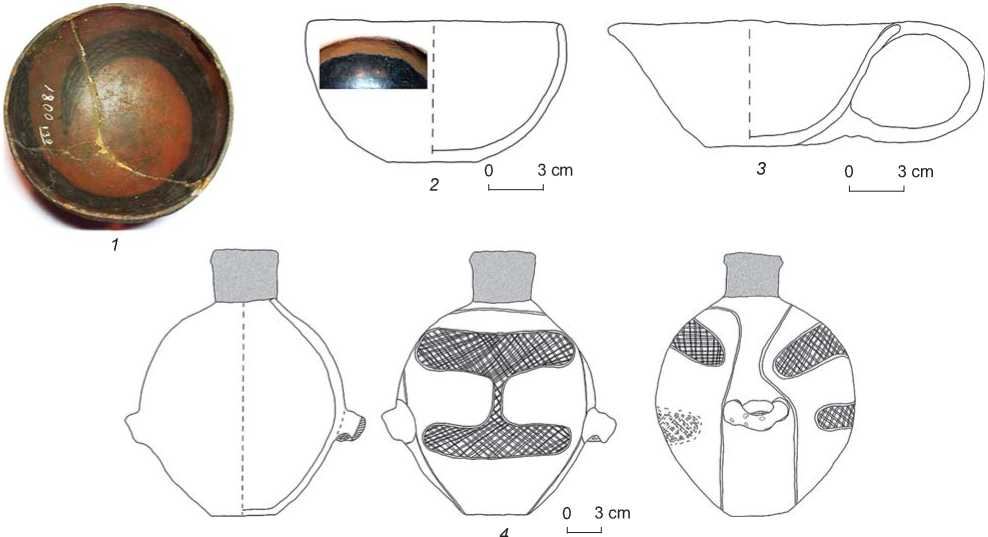

Ceramic items. In the collection owned by MAE RAN, these are mostly bowls ( pucos ). Such vessels were widespread in the Late Ceramic period of the Northwestern Argentina cultures. In the collection, there are bowls with hemispherical and truncated conical shapes, characterized by a rough working. The diameters of their rims vary from 14.0 to 24.0 cm, their heights from 6.0 to 11.0 cm. The shapes of bowls from Pucará de Tilcara are not as diverse as those in assemblages from contemporaneous sites in the Province of Salta. The proportion of painted

Fig. 1. Artificially deformed skull from Pucará de Tilcara (collection 5148).

vessels is smaller than that in the collection from La Paya (Sprovieri, 2013: 56–68; Dmitrenko, 2018: 242– 244). Preference was given to spiral patterns. Images of snakes filled with a netlike ornament were often used (Fig. 2, 1 ). Such pottery pertains to the traditional Omaguaca type. The painting was performed with black paint against a red background. In several cases, a V-shaped pattern was used. Painting of this type is typical of the articles made by the Calchaquí Indians (Salta Province, the La Poma tradition). Unlike them, the Omaguaca painted black, fully or partially, the inner surface of hemispherical red ware bowls (Fig. 2, 2 ).

Among other ceramic shapes, noteworthy are painted small-size pseudo-aryballoi (Fig. 2, 4 ). These were decorated with geometric figures filled with netlike ornament, which is typical of the combined Inca-Omaguaca style. A series of materials once owned by various Inca communities is distinguished among the ceramics of Pucará de Tilcara (Calderari, Williams, 1991). The collection also includes spherical pots with coupled handles in the central part of the body or near the rim; mugs with loop-shaped handles; and low truncated conical vessels with very wide rims and large loop-shaped handles, similar to antique lamps in shape (Fig. 2, 3 ).

Stone items. The collection yields 19 grinders of irregular spherical form, made of coarse-grained bedrocks (various granitoids), and two flat grinding- stones of a very large size (51.0 cm long and 13.0 cm wide). The last two were broken off, and massive protruding handles were preserved at the surviving ends. Pronounced use-wear traces in the form of polish can be observed on the lateral and frontal surfaces of these items. Pecking technique was employed in manufacturing both tools. This is indicated by the traces on the grinders’ parts that were not used during working. A set composed of a large grinding-slab (57 cm long, 27.5 cm wide) and a flat oblong grinding-stone is unique for the collection. On the latter, a deep rounded recess on one side is equal to the slab in width. The products were rubbed by movements directed along the entire slab, as evidenced by the wear-traces on its surface.

The assemblage contains seven small stone mortars with recesses, rounded owing to wear. Remains of brown-red coloring matter are preserved on the working surface of one of them. Along with mortars, short cylindrical pestles were used. The collection yields a stone knife, similar to the Inca tumi knives in shape (Handbook…, 1946: 621). The items delivered without field numbers include 13 splinters and 6 blanks of tools made from black and transparentgray obsidian.

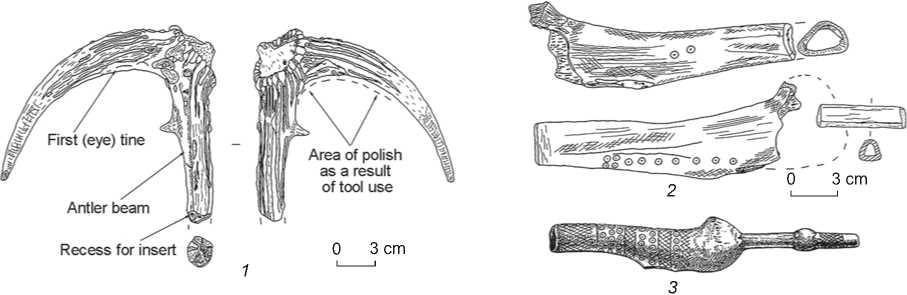

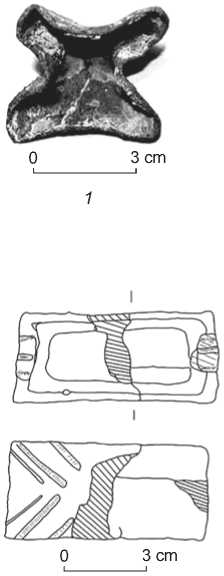

Antler and bone items. These constitute a considerable series of 29 specimens. According to the list provided by Ambrosetti, three tools were made

Fig. 2. Ceramics.

1 , 2 – hemispherical bowls; 3 – a lamp; 4 – a miniature pseudo-aryballos.

of Chilean guemal antlers ( Hippocamelus bisulcus ; “cerves chilensis”—the name from the inventory list). They are characterized by a standard shape and a number of unified treatment techniques. The tip of the antler beam was sawed off; then, a round recess was drilled out therein, obviously intended to secure an insert; and flattened flakes were made at the ends of the first (eye) tines (Fig. 3, 1 ). At the junctions between the beam and tines, a pronounced polish (probably, a result of tool use) is observed. Considering its location and the shape of the item, it can be assumed that the tool had an insert, which was put into the recess at the end of the beam and brought into operation by rotational movements through the use of tines.

Other unique items made of deer antlers are flutes (Fig. 3, 2). Only one of these is completed with a mouthpiece, while two others are extant in massive hollow parts of the base. Flutes in better condition have been found at other Omaguaca sites (Ibid.: 630). Owing to these materials, it is possible to reconstruct the initial shapes of instruments from the MAE RAN collection. The flutes were composed of two mouthpieces, which were either tubular bone-fragments or hollow pipes carved out of antlers, and a massive part made of the antler beam’s base. These elements were, obviously, connected using organic substances similar to rubber, or clay. Notably, in one flute, small holes (0.1 cm in diameter) were drilled out along a widened edge, apparently intended for more secure attachment of the instrument’s component parts. In addition, the collection contains two hollow pipes carved out of deer-antlers. These are similar to the flute mouthpieces in their shape at the end (Fig. 3, 4) and in the middle portion (Fig. 3, 5).

Fig. 3. Antler and bone tools.

1 – a tool made from Chilean guemal antler; 2 – reconstruction of a flute from Pucará de Tilcara; 3 – a flute from the collection of the Ethnographic Museum in Buenos Aires (Handbook…, 1946: 630); 4 , 5 – parts of antler flutes; 6 – a comb; 7 – a bone spatula; 8 – a fragment of an item with a “circular” ornament.

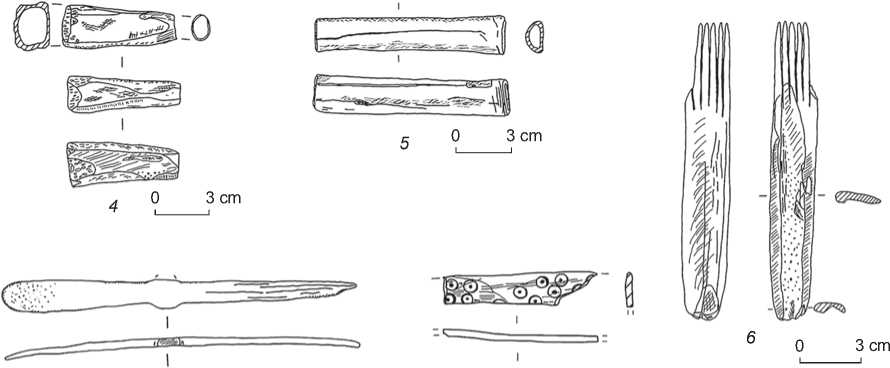

All bone tools are thoroughly polished. The surfaces of certain items are decorated with slotted, so-called circular ornaments, similar to that on the fragment of an item in the form of bone blade (Fig. 3, 8 ). Such decoration is also present on one of the flutes (Fig. 3, 2 ).

Among the bone items, noteworthy are three long narrow combs (Fig. 3, 6 ). The surfaces of these items, especially those of the cogs and their bases, were strongly polished. Taking into account the abundance of clothing fragments made of lama wool or plant fibers in the burials, as well as the shape and degree of polish of the combs, it can be assumed that they were used as ripples.

The collection contains thin bone tools (two intact ones and a fragment) referred to as “spatulas” in the foreign literature (Ibid.: Pl. 133) (Fig. 3, 7). Their length is 16.0–17.5 cm, the width is 1.6–1.7 cm. Utilization traces are concentrated mostly on the flattened surfaces of the items, and are directed diagonally, which rather suggests the use of the tools for treatment of clay, i.e. in pottery production (a definition given by N.A. Aleksashenko, a senior expert in the scientific- storage work of MAE RAN). This assumption is also evidenced by remains of black coloring matter in the spatula pores, as well as by traces of black paint on its surface. A wide flat tool with a slightly cut linear ornament on a thoroughly polished front surface may also pertain to this category (MAE, No. 1800-84). Remains of black paint that formerly covered the sides of the item are preserved on it. Paint at the pointed tip has been erased owing to wear. The tool is 13.5 cm long and 2.2 cm wide.

The collection includes a bone blank intended to manufacture a spoon, whose analog is stored in the collection of the Ambrosetti Ethnographic Museum (Zaburlín, Otero, 2014: 184, lam. 7).

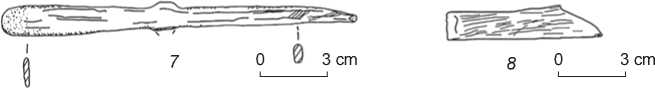

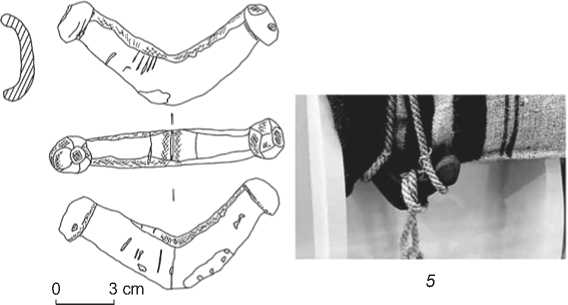

Items made of other organic materials. Owing to special features of the soils, the cultural layer of Tilcara provided the researchers with a large variety of finds made of organic materials. A series of wooden items includes flattened stands for burning aromatic substances (Fig. 4, 3 ), two spoons with long handles, a cylindrical beaker, V-shaped elements of harness (Fig. 4, 4 ) that were used to secure pack-cargoes transported on lamas (Fig. 4, 5 ), and two tools

Fig. 4. Copper ( 1 ) and wooden ( 2 – 5 ) items.

1 – a bell; 2 – a spatula; 3 – a stand for burning aromatic substances; 4 – a lama harness fastening element; 5 – reconstruction of its use (exposition of the Ambrosetti Ethnographic Museum).

resembling plain-back shovels. At one end of one such tool, a shank shifted towards the side edge is cut out. A longitudinal rounded recess for securing a removable shaft is made in the shank (Fig. 4, 2 ).

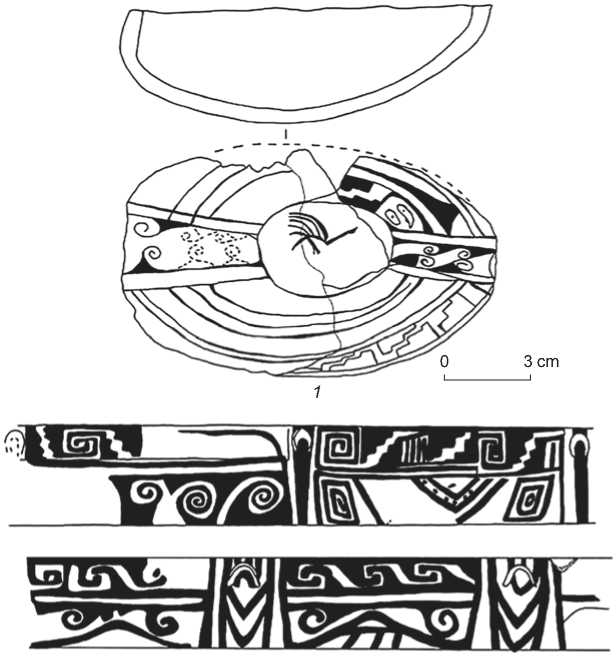

Noteworthy is a hemispherical bowl carved from half a pumpkin. The outer surface of the vessel is decorated with a geometric ornament made with the burning-out technique. Vessels of this type are frequent finds at the Puna sites, contemporaneous with Pucará de Tilcara (Handbook…, 1946: 626). In the center of the bowl, a running rhea is depicted (Fig. 5, 1), surrounded by compositions of ornament similar to that encountered on the classic bowls of the Calchaquí culture (Fig. 5, 2). On both sides of the bird figure, there are strips filled with floral ornament. As an indirect analogy, we can mention a myth of the Jivaro Indians about the moon that turned temporarily into a rhea, who, having quarreled with his cunning wife (a night bird auhu), climbed up to the heavens along a liana (https://www.indiansworld. org/Articles/.

Notably, the quarrel between the spouses started because of eaten yuvi pumpkins, and the auhu, following the rhea, “collected her clay pots and boards, on which women rub clay for modeling”. It is not clear so far whether this mythological subject is related to the Omaguaca and Calchaquí vessels, but it is interesting that ornamental compositions with a rhea surrounded by certain geometric and floral motifs occur exactly on calabashes and clay vessels. Taking into account the absence of folkloric mythological subjects known from the oral literature of the Central and Northwestern Argentina peoples (Berezkin, 2007: 273–281), such images can be of particular importance for studying the Omaguaca culture. As for the iconographic tradition, analogs of materials of pre-Inca and Inca periods of Northwestern Argentina are discovered far beyond the limits of Ecuador and Peru, which are the traditional habitat territory of the Jivaro Indians (Ibid.: 119).

Copper items. Among these, there are three plates which are halves of broken tweezers, a stick with a circular cross-section, and a bell made of a square copper plate with rounded corners (see Fig. 4, 1 ).

Fig. 5. Calabash with a burned-out ornament from Pucará de Tilcara ( 1 ) and tracing of ornaments on bowls from the settlement of La Paya ( 2 ).

0 3 cm

Some items in the collection without numbers or accompanying information about places of their discovery include: a necklace made of seeds; beads made of malachite; pieces of ocher; nutshells intended for manufacturing bells; maize grains found in a burial; a fragment of a charred maize cob; a calabash with a deepened ornament on its outer surface; wooden tools and obsidian splinters. These finds, originating from different features of Tilcara, were selected by Ambrosetti, who obviously wanted to send to MAE items made of a wide variety of materials, in order to represent the Omaguaca culture assemblage to the fullest extent possible.

Conclusions

Attribution of archaeological and cranial finds from the Pucará de Tilcara fortress, which are stored in MAE RAN, has made it possible to refine the information about their origin and to reveal a series of items that do not belong to the assemblage of this site. Analysis of the general catalogue of the Ambrosetti Ethnographic Museum has shown that the majority of the above materials from Pucará de Tilcara in the MAE RAN collection pertain to the excavations conducted in the northwestern part of the site in 1908–1910.

Studying the remaining documents has revealed numerous inconsistencies between different lists, and in some cases was of no help in determining the places of discovery of the items. For example, funerary ceramic urns from the materials of 1905 excavations in the Province of Salta are itemized in the general catalogue of the Ambrosetti Ethnographic Museum (hereinafter, the GC AEM) under the numbers of a series of stone tools from Tilcara specified in the list of MAE RAN (No. 200–213). According to the information received from employees of the Archaeological Department of AEM, the field numbers of finds of the first expedition of the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature in the general catalogue do not coincide with the numbers preserved on the items stored in the museum’s collection. In the GC AEM, instead of three grinding-slabs (790, 791, and 792) from the MAE list, painted bowls from the settlement of La Paya found during the second expedition of 1906 are recorded.

In spite of all difficulties, the materials available in MAE RAN contain important information about the Omaguaca Indians’ culture, which will be presented in detail in subsequent articles. The results of the study of the cranial specimens suggest that the Omaguaca Indians were able to perform specialized surgical manipulations. These results are also informative about the health status of the population that buried its members on the site.

A large series of ceramics, items made of bones, antler, and stones in the MAE RAN collection supplement the picture of economic activities of Pucará de Tilcara’s inhabitants. The presence of bichrome ceramics and bone tools for polishing the ceramics (presumably, with the remains of respective paints on the surfaces) argues for the manufacture of some vessels within the fortress. The inhabitants of Tilcara were also engaged in textile fabrication, which is indicated by bone combs for combing out wool, and indirect evidence of the use of lamas (wooden fittings to fasten loads). The assemblage contains a lot of artifacts confirming that the local population was engaged in agricultural activities: wooden spades and hoes; a large number of tools for rubbing plant products or mineral substances (grinders, mortars with pestles). This is evidenced by the presence of maize cobs and separate maize grains in the cultural layer.

Description of the MAE RAN collection provides new materials for restoration of the formerly isolated assemblage of Pucará de Tilcara. Since it is impossible to finish research into the fortress area destroyed by building works in the first half of the 20th century, it is also extremely important to study the already available sources for refining the microchronology and cultural and economic specifics of the site.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, Project No. 17-31-01092-ОГН МОЛ-А2.