Creative Tourism by Local Government? An Analysis of the Design of the First Public Policy in Brazil

Автор: Emmendoerfer M. L., Niquini W. T. R., Richards G., Ashton M. S. G.

Журнал: Креативные индустрии | Creative Industries R&D @creativejour

Рубрика: КУЛЬТУРНАЯ ПОЛИТИКА И РЕГУЛИРОВАНИЕ | CULTURAL POLICY AND REGULATION

Статья в выпуске: 1 (2), 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The main point is to understand the design of the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program (PPATC-2013) as a municipal public policy, analyzing the first creative tourism program implemented in Brazil. It seeks to contribute to the emerging field of creative tourism public policies, facilitating policy learning for managers and academics interested in the theme. Methodologically, pragmatist epistemology and ex-post-facto research were adopted, using a single case study. It employs methodological triangulation, combining documentary research (Multi-annual Plan, program guidelines, municipal reports), field observation, and interviews with public managers and policymakers (2017-2018). The analysis follows inductive logic with saturation of the apprehended narratives. As main results, critical limitations were identified in the design of PPATC-2013, such as: absence of tourism demand studies, centralized elaboration process, uncritical mimicry of external models, lack of community mapping of creative activities, and absence of a monitoring system. The program had a limited duration (2 years) and evolved into the Shed Tourism (in Portuguese, Turismo de Galpão) project. Among the main contributions and implications, the study demonstrated that tourism policies, with specific niches such as creative tourism, require adequate territorial diagnosis, participatory design process, contextual resignification of external experiences, and intersectoral articulation. It contributes to the preservation of institutional memory and offers lessons for the development of similar policies, emphasizing the need for adaptation to local specificities and effective community participation.

Tourism Policy, Creative Tourism, Cultural Tourism, Municipality

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/14134264

IDR: 14134264 | УДК: 338.48-44(816.1-25) | DOI: 10.7868/S3033671625020047

Текст статьи Creative Tourism by Local Government? An Analysis of the Design of the First Public Policy in Brazil

Studies on Tourism Public Policies (TPP) at the local level are incipient when compared to those at state (Zambrano-Pontón et al., 2019) and national levels (Scott, 2011), given that municipalities have predominantly assumed the responsibility of executing public policies, especially in federative countries. Studies on the design of such policies are even rarer in the tourism context (Emmendoerfer et al., 2021b).

In Brazil, on one hand, the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988, in its article 180, indicates that public action regarding tourism should be the responsibility of the three spheres of power. Thus, it is incumbent upon all to promote and encourage tourism as a factor of social and economic development (Brasil, 1988). On the other hand, there are constraints and restrictions on resource availability for specific sectors, such as tourism, at the municipal level due to the fiscal and tax federative system in force in Brazil.

It is understood that new demands generated by tourism activity to solve problems or create new “economic opportunities” (Velasco, 2011) enable municipal public authorities to intervene in the organization and promotion of tourism activity. Thus, it is argued that municipalities can develop the capacity to produce tourism public policies, which “after being designed and formulated, unfold into plans, programs, projects, databases or information systems and research” (Souza, 2006, p. 26). Such policies can solve or mitigate public problems, as well as promote the development of tourism activities, which can become investment targets to overcome situations of stagnation or retraction of this sector in municipalities.

In this sense, under ideal conditions of self-sufficiency of municipal governments, they would have the capacity to develop their public policies that would promote specific actions for the locality, without the obligation only to implement top-down policies. The practice of vertical implementation, which may be common in the tourism sector, is considered, in many cases, inadequate for territories, precisely because it does not consider their specificities. Thus, the peculiarities of each municipality can define how public policies should be elaborated to meet their urgencies (Silva, 2015), as well as opportunities related to tourism.

In this sense, the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program was verified as a public policy for tourism development, distinguished by its creativity at the local level. This makes it a reference, as it is the first municipality in Brazil to launch such a program, justifying its choice. In this sense, the objective of this study is to understand the design of the Creative Tourism Program as a public policy in the municipality of Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil.

The contemporaneity of creative tourism practice can be treated as something also relevant for being an alternative to awaken experience tourism or enhance tourist places with a strategy for sustainability (Negrão et al., 2025). According to Emmendoerfer (2019a), studies on creative tourism public policies, generated and managed by the municipal government itself, are emerging and diffuse, and sometimes, with restricted information and lacking details in access via the internet.

This hinders policy learning practices for practitioners and academics interested in understanding the configuration and processes related to creative tourism fostered by local governments, whose products and results of public investment should be shared in an accessible way to minimize unnecessary reinvestments (Hall, 2011). Such difficulty can be minimized through actions and studies that focus on transparency and open science, thereby assisting in the qualitative recording of details to preserve the memory of public actions that are well or incipiently successful.

Methods

In methodological terms, the case studied, designated for this research, was PPATC-2013, which consists of the initials of the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program, added to the year of its materialization and public disclosure. This ex-post-facto research was conducted by Emmendoerfer et al. (2021) within the scope of the Research Group on Management and Development of Creative Territories (GDTeC). To achieve the proposed objective, pragmatist epistemology was adopted (Dewey, 2007) in which the focus is on understanding how the Design of PPATC-2013 was made from existing and appropriate experiences that were articulated to influence tourism in the municipality under study. In this sense, the following data collection techniques were applied: bibliographic, documentary, field observation, and interviews.

The bibliographic research, available in the references of this text, was helpful in situating part of the theory that guided the elaboration of the design of PPATC-2013. From this section, the design of PPATC-2013 was described, based on documentary sources made available in printed form such as the Multi-annual Plan – PPA 2014-2017 of Porto Alegre and the Basic Guidelines of the Program (Porto Alegre, 2013), which were identified in direct contact and electronic communications with public managers and policymakers co-responsible for the Program under study, instituted by the Municipal Tourism Secretariat of the Porto Alegre City Hall, Rio Grande do Sul, in the management mandate 2013-2016. It is noteworthy that in loco observations were carried out with annotations by the researchers and interviews with these research participants in the period 2017-2018. The collected data enabled the organization of the third section of this study, which focused on the design of the Program, under inductive logic and saturation of the apprehended narratives. The last section, before the conclusions and final considerations, was dedicated to discussions and reflections on the design of PPATC-2013, considering the specialized bibliographic review.

It is noteworthythat additional information with details of the methodological path employed to achieve part of the results on the theme under study can be obtained in the work of Niquini (2019), part of a broader investigation project with approval (code process: 2.831.776) in the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) in Brazil.

The Design of the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program – PPATC-2013

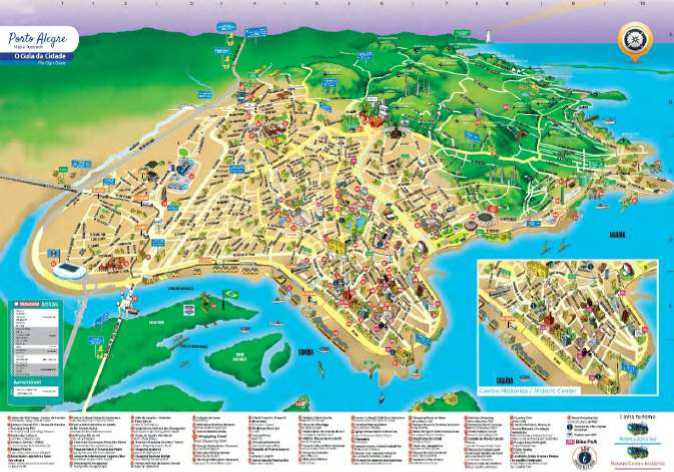

The municipality of Porto Alegre, as shown in Fig. 1, is recognized for its expertise in business tourism and major events, making it a reference in Brazil for these segments. According to Canton (2009), business and events tourism has emerged as a key sector to serve this demanding public, incorporating creative and innovative activities to meet these new demands. Porto Alegre’s inclination towards business and events tourism was evident in 2016, when the city ranked third in the international events ranking, attracting 182 million visitors (PORTO ALEGRE, 2016). It maintained its position among the 10 main event destinations in Brazil in 2019 (Redação O Sul, 2020).

Figure 1 – Map of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Source: own elaboration from public domain images on the Internet

Despite this, the stay of two to three days of tourists in the city has remained relatively unchanged since the beginning of this second decade of the 21st century, which may be associated with the absence of diversified and consolidated leisure tourism that could extend the stay of tourists in the city. Such a problem was one of the inducing motives to foster new tourism and leisure activities aimed at consolidating the city in the national scenario, developing tourist routes according to Fig. 2.

Figure 2 – Tourist map of Porto Alegre

Source: Fecomercio (2021)

It was verified that the deficit of permanence and the small demand for leisure tourism in Porto Alegre were not seen as problems, but rather as opportunities to modify this scenario. In his studies, Subirats (2006) externalizes the importance of a good definition of the problem, which then becomes the starting point for the design of a public policy. From the identification of the problem, the municipal public authority understands that it is necessary to develop a new means of offering tourism activities through the introduction of the concept of creative tourism in the municipality. Thus, PPTAC-2013 emerged as an alternative in the search to consolidate leisure tourism activity, in addition to business and events.

Porto Alegre has been considered one of the best Brazilian capitals to live, work, do business and study based on the Human Development Index (HDI), gaining prominence by the United Nations (UN) as the No. 1 Metropolis in quality of life in Brazil, three times democratic for its Participatory Budget (Encontra Rio Grande do Sul, 2020). This municipality can be considered a pioneer in creative tourism in Brazil, mainly due to the international recognition of the Creative Tourism Network (CTN), whose scope is to develop creative tourism. It is noteworthy that creative tourism gained prominence at the international level from 2010, with the creation and tourism promotion actions of this network, headquartered at the Fundació Societat i Cultura (FUSIC) in Barcelona, Spain. This network aims to promote destinations that specialize in creative tourism, highlighting cities with a strong interest and potential to develop this activity. In this context, policymakers from the Municipal Tourism Secretariat of Porto Alegre participated in the International Tourism Fair (FITUR), in January 2012, in the city of Madrid, Spain, to promote the city of Porto Alegre. During the fair, the representatives of Porto Alegre tourism encountered for the first time the concept of creative tourism through this network. Until that moment, the concept of creative tourism was unknown to Porto Alegre policymakers, which is when interest was aroused and its possible application in the municipality was envisioned (Creative Tourism Network, 2013).

The design of the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program – PPTAC, instituted by the Municipal Tourism Secretariat of the Porto Alegre City Hall in the period 2013-2016, sought to bet on innovation by implementing the concept of creative tourism in a pioneering way in Brazil, by publicly presenting basic guidelines for this tourism activity. These indicate that the Program was based on other consolidated Creative Tourism destinations, such as Paris, Barcelona, and Santa Fe, with advisory from the CTN network (Porto Alegre, 2013, p. 14). The design of PPATC-2013 initially began to be elaborated “in January 2013, centralized to one civil servant and one consultant, who were at the forefront of all research on the concept of creative tourism, translations of bibliography and formation of the program” (Niquini, 2019, p.42).

PPTAC-2013 was publicly launched in June 2013, together with the first workshops to be offered in creative tourism in the municipality, with the logo (identity seal of the Program) as a symbolic form (Fig. 3) of this concept.

Figure 3 – Logo of the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program

Source: Porto Alegre (2013)

The logo employed can be considered a marketing innovation in the public sector to (re)position and differentiate the image of the municipality (Emmendoerfer, 2019c), which had in the management plan (2013-2016) of the Municipal Prefecture of Porto Alegre, creative tourism as a means of developing an ambience of the municipality for innovation, enhancing the notion of an innovative city (Municipal Prefecture of Porto Alegre, 2021).

Despite this, it served as a basis for defining the general objective of PPATC-2013, which was to “implement and develop creative tourism in the municipality of Porto Alegre as a source of diversification of the tourism offer and promotion of local cultural, social, and economic sustainability” (Porto Alegre, 2013, p. 24). Based on the studies and definition of the concept by Richards and Raymond (2000), other categorizations were employed regarding creative tourism. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) describes that “provoking a change from conventional heritage-based cultural tourism models to new creative tourism models centered on contemporary creativity, innovation and intangible content” (OECD, 2014).

As established in the basic guidelines of PPATC-2013, its objective was aligned with global and national agendas for the development of the creative economy through tourism (Emmendoerfer et al., 2018; Emmendoerfer et al., 2021a), which strengthened the appeal in favor of creative tourism and the potential to obtain access to supra-municipal public resources.

Thus, aiming to deal with the problem that involved the introduction of creative tourism as a means of adding value and dynamizing tourism in the municipality, specific objectives were established:

-

• Valorize local culture, contributing to the preservation of the tangible and intangible heritage of the destination and the consequent promotion of new forms of local cultural sustainability;

-

• Cultural enrichment and improvement of hospitality resulting from exchanges of experiences between tourists and residents;

-

• Greater independence from destination seasonality, which makes it viable as an alternative for low seasons;

-

• Aggregation of local sectors that had no direct connection with tourism, such as social technologies, science, design, fostering their activities and generating new income alternatives; and

-

• Diversification of the destination’s offer and the possibility of complementing other tourism modalities.

The main categories (economic segments) foreseen in PPATC were: visual arts, performing arts, handicrafts, music, gaucho traditionalism and education, social technology, science and technology, reading, multimedia, gastronomy, fashion, and quality of life.

It was observed that to assist the Program, structural partnerships were considered in ateliers and art schools, cultural centers, gaucho tradition centers (CTGs), gastronomy schools; creative schools; public spaces; art galleries; museums and theaters; rural properties and other entities and institutions (Porto Alegre, 2013, p. 24).

To verify the creative potential of Porto Alegre, an inventory of the city’s possibilities linked to the creative was carried out, observing the originality and renowned artists and with something autochthonous linked to Porto Alegre. To encourage other actors to participate in the program, the municipal public authority issued a public call in a city newspaper, informing and presenting PPATC-2013.

Following the launch of the Basic Guidelines for the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program, the activities (workshops related to the categories above) were already operational in the municipality on an experimental basis. Such experimentalism reiterated the possibility of developing a concept still new in Brazil to solve the problem identified in the municipality’s tourism, attributing to it the status of public authority, making it relevant to be part of the public agenda. It is noteworthy that in these moments, some ideas/actions are discussed and others are not, often these discussions only occur when there is a favorable context for this to happen (Carvalho, 2015), as was the year 2013, which was even on the eve of the edition of the Men’s Football World Cup in Brazil. Thus, PPATC-2013 was inserted in the Multi-annual Plan – PPA 2014-2017 by the Porto Alegre City Hall, as a public action of strategic innovation for local tourism development, where creative tourism is explicit with a budget of US$ 60,000 for the first two years and evaluation criteria for this action centered on the number of new attractions and/ or creative tourism activities in the period (Porto Alegre, 2014, p.103).

In the eyes of the public authority, creative tourism should be viewed as a viable alternative to address local challenges or enhance tourism within its municipality. Creativity can be an attractive policy option to stimulate a series of economic, cultural, and social results (Richards, 2011). The potential of places that have been revitalized by creativity is enormous. The public authority has numerous possibilities to work with creative tourism, not only involving the tourist, but also the residents who seek means to reinvent themselves or even learn from something that is part of their daily life, but that never captivated the public authority and the community itself (Mediotte et al., 2024). Cities like London, Rotterdam, or Shanghai, once at the forefront of the old industrial economy, are now also at the forefront of the creative economy, at least in part, because of their abundant supply of rehabilitated “creative spaces” (Richards, 2011). These are some possible paths to work with creative tourism through public policies.

Gastal and Moesch (2007, p.42) argue that “[...] a public policy must have clarity about the conception of tourism it defends, about what vision of development it seeks and about what its commitments are”. According to Schindler (2014, p. 31), “tourism public policies are the set of decisions and actions taken by the State to initiate and/or develop tourism activity in a given locality, seeking to benefit both the autochthonous community and those who visit it”.

Already in October 2013, the 1st Brazilian Conference on Creative Tourism took place in Porto Alegre, to legitimize institutional relations with the international CTN network, inviting its founder, Caroline Couret, as well as researcher Greg Richards, to participate in this event. Their participation reiterated the position of the municipality and participants as pioneers of creative tourism, respectively, at local and global levels, recorded in the Declaration on the Future of Creative Tourism (Richards, 2013).

This conference also sought to demonstrate the integration of the strategic axes of the Program, publicly presenting the activity schedule of the Design of PPATC for the first year 2014 (Emmendoerfer et al., 2021b). Furthermore, the program aimed to stand out in the national and international scenario, as already mentioned, but also to expand tourism as a form of socioeconomic development of Porto Alegre.

Even with this strategic direction and based on the problem definition and studies by Subirats (2006), it is corroborated that public problems still do not receive the necessary attention, because from the interviews with PPATC-2013 policymakers, it was verified that there was no more in-depth study of the problem that motivated the design of the Program.

One of the factors identified was the lack of supply and demand research and research on the tourist profile to identify which tourism segment would be suitable for the city and even if there was already some demand for tourism activities focused on creativity and innovation. In theoretical terms, it was observed that the problem did not receive the necessary attention, there was no in-depth research on the market, supply, tourism demand, and profile of creative tourism for Porto Alegre.

Another aspect little valued in the design of PPATC-2013 was the form of insertion of the offering actors. About this, the public authority sought the names of artists with recognition who worked with the traditional creative economy (artistic-cultural). It was observed that the design failed to identify the real characteristics of the municipality and the community in the search for activities that could be characterized as creative. Based on the interviews of policymakers, the workshops offered in Porto Alegre could be done anywhere, decharacterizing what is expected from activities focused on creative tourism, where place and creative placemaking make the difference in this tourism experience.

These criticalities may have been inducing motives for the non-continuation of PPATC activities beyond its experimentalism, reverberating in the incipience of data observed about this Program in the annual reports of management activities of the Municipal Prefecture of Porto Alegre.

Despite observing that there were failures in the definition of the problem and consequently in the design of the Program, the public authority had established that the intention was to foster and establish the city of Porto Alegre in the theme of leisure tourism through PPATC-2013, which lasted two years, according to the annual reports of municipal management activities. This indicated the appropriation of creative tourism as innovation in the public sector centered on a fast policy of marketing, which, according to Peck and Theodore (2015), is a way to operationalize experimental local government, through visual arts, events, and advertising to quickly promote an idea of socioeconomic development project for the municipality.

It was evident that the European concept was incorporated into the design of PPATC-2013, likely due to the scarcity of studies on whether the activity would be effectively practicable in the city. It is understood that a tourism public policy design should emerge from the everyday reality of its locality, respecting regionalization and community needs.

Another aspect observed was the design of public policy based on mimicry (Boutinet, 1990), that is, copies of policies that occur in other places. Often, governments use existing models in other locations, without worrying about the necessary resignifications. Being inspired by programs that have worked is valuable, but implementing a copy from another location is not particularly interesting. Each site has peculiarities that should be observed when developing a tourism public policy design.

In creative tourism, singularity is essential for developing unique creative activities. It becomes necessary to observe that each locality that wishes to implement creative tourism should collaborate with the local community to map cultural and historical elements that can be used. It is important to be based on programs that worked, but the necessary resignifications must occur; otherwise, it will make creative tourism just another product for its locality. In his studies, Richards (2011) indicates that creativity can happen anywhere. However, the important thing is to relate the creative process with the destination and insert it into local culture and identity. In Porto Alegre, the inclusion of the gaucho traditionalism category is the program’s differential, as it is the only place where gaucho culture can be experienced in its most traditional form without theatricalization.

In the design of the Program, mainly the publicized and available on the internet, the presence without major highlights of the gaucho tradition is observed, which should be more articulated with tourism activities in the municipality. According to PPATC-2013 policymakers, the state of Rio Grande do Sul’s rich vocational and cultural landscape, shaped by colonization, is home to several ethnicities. Recognizing the value of this cultural heritage, the public authority sought to leverage the traditional gaucho culture.

This can be described as a cultural Movement originated in Rio Grande do Sul that expresses the attachment of part of the state’s population to countryside things and to mythified historical episodes of the region. In addition, it has as symbolic representation the old gauchos - a social type of the Pampa (which also serves as mythical representation of the state’s inhabitants) - and, therefore, this manifestation is also called “gauchismo”. The Movement has its cultural expressions demonstrated in music, dance, clothing, costumes, games, taste for horses, and countryside activities, as well as various expressions inspired by rural reality (Konflanz, 2013, p. 22).

The implementation of the PPATC-2013 design was incipient, and the Shed Tourism project emerged as a redesign, not formally revisited, of the Program and as the main action to make it effective within the scope of PPA 2014-2017 of Porto Alegre. The idea that Shed Tourism is a (re)design of the Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program is an emerging analysis resulting from this research focused on the analysis of creative tourism public policy (Hümmel, 2016; Niquini, 2019; Emmendoerfer et al., 2021b).

However, it is recognized that Shed Tourism was only possible due to the existence of Porto Alegre Creative Tourism, which was the basis of its inspiration. Molina (2013) explains that each place should implement creative tourism as desired, being that in each site, this will occur from local peculiarities. The concept, created in Europe and now implemented in several countries, does not follow a model, but rather the characteristics already mentioned. Creative tourism can work successfully in one place, but fail in another, making use of the same characteristics if there is transposition of a plan (Molina, 2011). In this way, one can be based on models that worked, but the necessary resignifications for each place are essential (Emmendoerfer et al., 2023).

It is noteworthy that Shed Tourism, for happening within an event already strengthened in the city, had greater demand and today is already part of the

Farroupilha Camp. This event was born together with the creation of Harmony Park (av. José Loureiro da Silva, 255, Porto Alegre, RS), in 1981. Since then, between September 7 and 20, one of the largest folkloric festivals in Brazil takes place there, which brings together almost 400 entities, being almost 90% of them of cultural nature, with an average total visitation estimated at a number close to one million per edition. Spanning 65 hectares, the park’s landscape, typically characterized by elements of gaucho countryside tradition, including outdoor barbecues and a creole shed, transforms in September by demobilizing its children’s recreation areas, sand football courts, volleyball courts, fishing spots, and aero and nautimodeling facilities to accommodate the Farroupilha Camp. The event offers a series of services, such as a food court, handicraft and literature fairs, bathrooms, a health post, a free wireless internet signal, bank terminals, security, and guarded parking (Porto Alegre, 2021).

Thus, in this annual creative event, creative tourism is called shed tourism, where the essential characteristics of PPATC are maintained, being the only place where activities related to the program happen in the city, with involvement of people from various other localities in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Discussions and Implications on the Design of PPATC-2013

A Tourism Public Policy (TPP) design can be analyzed based on its societal benefits, which can be verified through the reach of its actions and activities, as well as through the evaluation of TPP results. This serves for transparency and public accountability, as well as contributing to collective learning in tourism public policies. However, data and information about these aspects concerning PPATC-2013 were not identified in the research. Why?

A fact that justifies this occurrence is the lack of explicit updates to institutional communication regarding the original design of PPATC-2013 by the co-responsible policymakers and public managers. This was observed during the in loco field research and in dialogue with research participants, whose records, readjustments and updates in the Program did not occur. The absence of this systematized and computerized process can compromise the qualified understanding and effectiveness of the design of any program or public policy, as well as trivialize the quality of work performed by professionals and public servants in the Tourism sector.

This also enhances the essentially promotional and rhetorical dimension of TPP, by not making effective use of planning instruments, activity promotion, or ways to solve problems arising from tourism activity. Velasco (2011) also expresses that public policies are recurrent in governments; however, there is little materialization of what was formulated in government plans. In summary, PPATC-2013 had an important aspect of political dimension at the municipal level: supporting the municipal government plan regarding innovation, at least in terms of introducing Creative Tourism as a novelty (Emmendoerfer, 2019b), potentially applicable to the reality of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Public policies that are not elaborated from absolute necessity, most of the time, become poorly executed and without satisfactory results, or even become unfeasible in their experimentalism. According to De Paula and Moesch (2013, p. 191), public policies at the macro level are built by “mistakes, such as: weak articulation with other sectoral policies, centralization of planning and coordination of tourism policy, absence of clear definition of objectives, goals and priorities”. Public policies should be created and designed in a co-participatory way from the absolute necessity of their territory (Hall, 2011). When all policies are developed in the municipality with local and regional participation in the elaboration of public policies, it is avoided that the adoption of a top-down model occurs. When it comes to the absolute necessity of the place and participation, investment is made in programs that can be well implemented and have good results, meeting the real demand.

Given the above, it is verified that studies related to public policies in the scope of tourism are still primary and without theoretical deepening. However, the study in question aims to contribute to the field of tourism public policy studies, serving as a resource for other researchers. It is observed that policies are elaborated without assessing the municipality’s absolute necessity and without the necessary analyses for constructing a consistent public policy. Thus, understanding the design of tourism public policy is an adequate starting point for the analyst who is engaged in this task.

Therefore, as implications of these results and discussions, the lessons learned from the experience of PPATC-2013 were relevant, including the finding that “a public policy design based on mimicry, that is, copies of policies that occur in other places” can be problematic when there are no “necessary resignifications” for the local context (Emmendoerfer et al., 2021). Therefore, guidelines are proposed for the design of creative tourism public policies, considering resources and capacities in a strategy for sustainability and aspects of the creative bioeconomy (Negrão et al., 2025) that can be extensible to other niches or focuses of tourism development at the local level, especially in Global South countries:

-

• Foundation and Diagnosis: Evaluates the quality of the conceptual base and territorial diagnosis that support the policy in the short, medium, and long term;

-

• Design Process: Examines the methodology and participation in the policy elaboration process;

-

• Programmatic Structure: Analyzes the coherence and adequacy of the proposed objectives, strategies, and instruments;

-

• Implementation and Management: Evaluates the institutional arrangements and management mechanisms foreseen;

-

• Monitoring and Evaluation: Examines the systems for monitoring and evaluating results;

-

• Sustainability and Continuity: Analyzes the mechanisms of sustainability and continuity of the policy.

The proposition of the above guidelines was based on the results of the PPATC-2013 study, with particular attention to the limitations or failures identified (Hall, 2011), as they offered the necessary insights in the design of future policies, considering their applicability both for ex-ante analysis (during the design process) and ex-post (for evaluation of implemented policies). It is noteworthy that such guidelines require applications in cities, as well as validations from future research.

Conclusions

Research on tourism public policies has evolved into a complex and underdeveloped field, gradually gaining traction among scholars and prompting public managers to consider the impacts on tourism planning and management.

The Porto Alegre Creative Tourism Program can be considered by policymakers who seek to elaborate creative tourism policies in the country. The program can be seen as a reference because, for its elaboration, there was extensive work to understand the concept still little disseminated. Based on the studies, the program’s basic guidelines were developed around the concept of creative tourism, inspiring other municipalities to create similar programs.

Thus, Creative Tourism practices from other places can inspire and define projects and tourism public policies; however, PPATC-2013 demonstrated that it is necessary to resignify and articulate the proposed design with traditional practices of the place or region. Such articulation requires managers and streetlevel bureaucrats trained to deal with these new demands in the tourism trade, but also with providers of cultural goods and services, so that from this integration, benefits occur for the sectors and their stakeholders.

This means that a good project can be more expressive and generate more beneficial results for the sector than a program looking for projects that can “work” and be effective. Therefore, a creative tourism public policy design may be distant from reality in terms of its effectiveness, necessitating a redesign or the decision to end a program that was born prematurely, lacking sufficient content and dialogue with potential interested parties.

However, this study demonstrated that creative tourism can be an alternative to dynamize and develop places that already have consolidated tourism, elevating activities that were not previously thought for the tourist, evidencing the resident as an integrated part and provider of activities focused on the creative nature. Another perspective of creative tourism involves utilizing underutilized spaces in the city to counterbalance the massification of tourism activity, thereby taking tourists to lesser-explored areas and potentially boosting tourism in those sites.

Another perspective on creative tourism is to use it as an alternative to develop tourism in cities that do not offer tourism activities. Creative tourism becomes an alternative for a municipality that seeks to develop tourism as an opportunity for economic and social development, encourages entrepreneurship in the tourism sector in small cities, generating new job vacancies and elevating the city to consolidate itself in the field of tourism.

As future research, it is suggested that work be done to verify if the activities of Shed Tourism had continuity, by the providers, public authority, or both. Moreover, from the concept of creative tourism, studies may emerge for greater understanding of the theme and enable work in places that do not practice tourism activity, but that can be fostered by creative tourism. Thus, it is expected that this work will inspire other interested parties to continue the studies, exploring new areas beyond the Brazilian capitals of Recife and Brasília, which have been developing creative tourism as an alternative. In this sense, the experience reported and discussed in this dissertation can provide advances for these and other localities in Brazil that seek to develop tourism public policies, including creative tourism as something focused or integrated with other actions in progress at municipal and regional levels.