Cultural ties across taiga and steppe: material culture from the medieval Lower Angara river and Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV

Автор: Senotrusova P.O., Mandryka P.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145387

IDR: 145145387 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.3.092-099

Текст обзорной статьи Cultural ties across taiga and steppe: material culture from the medieval Lower Angara river and Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV

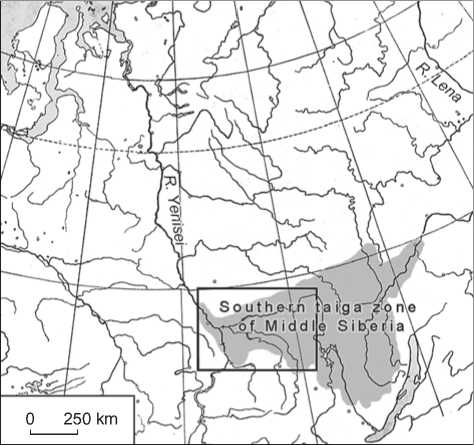

Over the past two decades, large-scale archaeological studies have been carried out in the southern taiga zone of the Lower Angara River (Fig. 1), significantly expanding the knowledge base for understanding the region’s medieval history. A complex of settlements and monuments was discovered near the town of Lesosibirsk, in the valley of the Yenisei River, near its intersection with the Angara. On the basis of a number of fortified settlements belonging to the 11th–14th centuries, the ceramic sequence of this period has been well studied (Mandryka, Biryuleva, Senotrusova, 2013). Researchers have also investigated 130 burials from the early second millennium in the Lower Angara region*, making it possible to reconstruct funerary rites and understand the Lesosibirsk archaeological culture in great detail (Boguchanskaya arkheologicheskaya ekspeditsiya, 2015: 528–529; Senotrusova, Mandryka, Poshekhonova, 2014; Mandryka, Senotrusova, 2018). A considerable number of imported objects and/or their imitations were found in the Lower Angara burials. The comparative assemblages

Cultural influences

In the studies of medieval cultures from the taiga zone of Eurasia, technological and cultural innovations are often associated with the steppe belt, since state entities, which included and influenced peripheral forest regions, were centered primarily in the steppes during the Middle Ages. Consequently, political and cultural developments in the Eurasian steppes had important impacts on the taiga population.

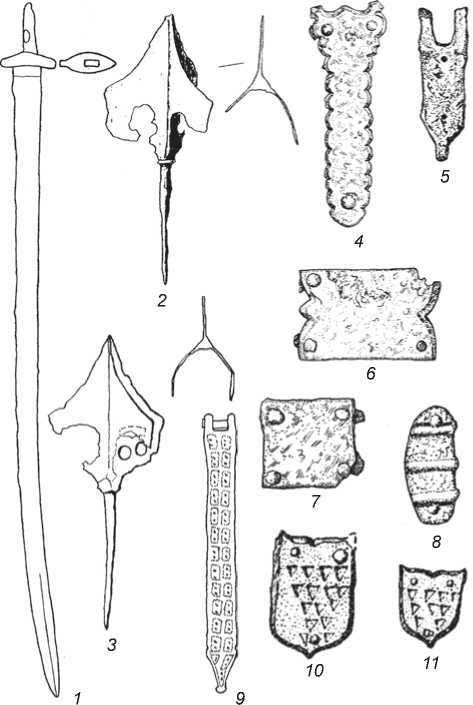

Influence of the steppe cultures . By the beginning of the second millennium AD, the southern taiga of Middle Siberia was a part of the sphere of influence of the Kyrgyz Khaganate. Rashid al-Din mentioned this fact, pointing out that the northern border of the state of the Yenisei Kyrgyz reached the mouth of the Angara River (1952: 102). A number of scholars directly linked medieval burials found in the Angara region, based on the practice of secondary cremation, with Turkic-speaking peoples, or specifically with the “Yenisei Kyrgyz people” (Volokitin, Ineshin, 1991: 146; Leontiev, 1999: 21) and their Krasnoyarsk-Kansk cultural variant (Klyashtorny, Savinov, 2005: 271). At the same time, direct archaeological evidence for Kyrgyz influence on the taiga population is not extensive. In the assemblage at Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV, we identified only a small number of objects that can be directly associated with the Yenisei Kyrgyz culture. These objects include a double-edged saber (Fig. 2, 1 ), iron hinged belt tips (Fig. 2, 4 , 5 , 9 ), and elements of two belt sets with rectangular and ovate iron overlays (Fig. 2, 6–8 ). These artifacts have parallels in the Malinovka subset of the Askiz culture. Several objects of Kyrgyz appearance were also recovered at the Dolonovka burial at the site of Koda-2, including three-bladed arrowheads (Fig. 2, 2 , 3 ) and belt iron overlays with a shield form, decorated with triangular scales (Fig. 2, 10 , 11 ) (Volokitin, Ineshin, 1991; Basova, 2016).

The next pulse of cultural influence came from the south, or rather southeast, and was associated with the

Fig. 1 . Location of the research area.

Fig. 2 . Iron objects of Kyrgyz appearance from the southern taiga zone of Middle Siberia.

1 , 4–9 – from Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV; 2 , 3 , 10 , 11 – from the burial in the area of the Dolonovka stretch of the Bratsk water reservoir.

conquests of the Chingissid Mongols. The accession of southern Siberia, including the Kyrgyz Khaganate, into the Mongol Empire must have influenced its northern taiga neighbors. According to historical records, this process began formally in 1207, and the Yenisei Kyrgyz were ultimately defeated in 1218 after the punitive expedition by Jochi (Bartold, 1963: 507). In 1227, southern Siberia and adjacent northern lands became a part of the “Ulus” (nation) of the Great Khan. In 1260, after the victory of Kublai over Ariq Böke, the Altai-Sayan highlands became a possession of the Yuan dynasty (Savinov, 1990: 129). Probably the only historical source from the Mongolian period that directly mentions Angara is the legendary tale of a trip by three noblemen down this river during the reign of Surhuktani (Rashid al-Din, 1952: 102). Despite the mythical nature of the events described, the mere mention of the Angara in the Mongolian sources is noteworthy.

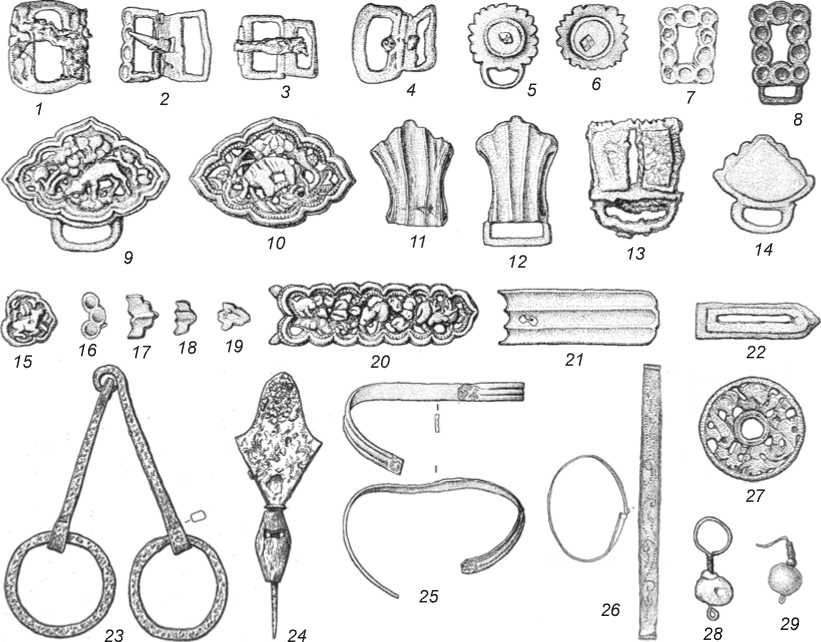

New goods became widespread on the Lower Angara in the Mongolian period, such as question-mark shaped earrings (Fig. 3, 28 , 29 ), wide, flat arrowheads (Fig. 3, 24 ), jointed bits with circular cheek-pieces (Fig. 3, 23 ), coin-shaped amulets (Fig. 3, 27 ), plate-metal bracelets (Fig. 3, 25 , 26 ), glass, faience, and ceramic beads;

as well as metal elements of composite belts with plaque-like attachment hooks (Fig. 3, 1–22 ), which are particularly noteworthy. The “Mongolian” style of belts already emerged in the Chingissid period. Its main elements were large, plaque-like belt attachments with a loop, two-part buckles, densely set miniature overlays (lunulae), and large subrectangular belt tips; a distinctive feature of such belts was the absence of hanging straps or overlays with slits (Kramarovsky, 2001: 69). Belts played an important role in the life of Mongolian soldiers; servings as markers of social status, valor, and nobility.

From the Angara River region, elements from seven composite belts are known, originating from closed burial contexts. These were cast of complex brass alloys with a predominance of lead and tin-lead bronzes. Elements of such belts were apparently made by the artisans at one time, to serve as part of a single complete set. High-quality and technologically complex metal alloys suggest that these belts were produced in artisanal centers and reached Siberia from a single workshop (or several workshops in close coordination) working under the orders of local elites. The closest known parallels to the Angara belts can be found in the Krasnoyarsk forest-steppe and southern

Fig. 3 . Objects of Mongolian appearance from Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV in the southern taiga zone of Middle Siberia.

1–4 – bronze, iron; 5–22 , 25–27 – bronze; 23 – iron; 24 – iron, horn; 28 , 29 – bronze, glass.

Fig. 4 . Lower Ob bronze objects from Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV.

regions of Western Siberia (Senotrusova, Mandryka, Tishkin, 2015: 122, 123).

The belts recovered from the Angara region were prestige objects. They are distinguished by high quality of manufacturing and sophistication of their aesthetic composition. This is particularly true of a belt showing an image of a fallow deer under a sprawling tree (Fig. 3, 9 , 10 ). Such finds occur quite rare in the territory of Eurasia, and serve as important evidence of the influence of Mongolian culture. Some scholars consider belts with similar representations as belonging to the category of ceremonial hunting belts, which were used in the 1240s–1270s to mid 14th century (Kramarovsky, 2001: 56, 65).

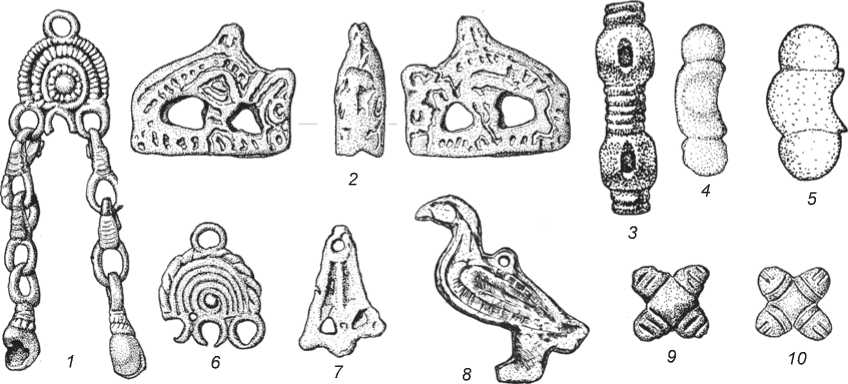

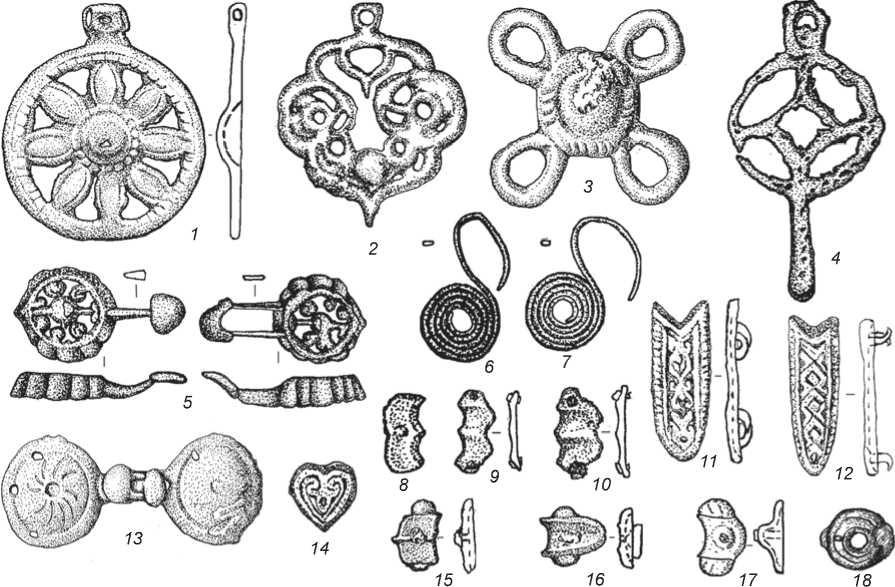

Influence of Western Siberian cultures . The medieval inhabitants of the Lower Angara taiga had stable cultural ties with the population of Western Siberia. Various bronze adornments came to Middle Siberia from the Lower Ob region. The collection from Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV contains openwork palmate pendants, archshaped dangle pendants, bell-shaped openwork pendants (Fig. 4, 1 , 2 , 6 , 7 ), a flat pendant in the shape of a bird (Fig. 4, 8 ), embossed cylindrical beads (Fig. 4, 3 ), and other objects (Senotrusova, Mandryka, 2013). These discoveries show many parallels among the materials from the sites of the Lower Ob region, including the burial grounds of Barsovsky IV, Saygatinsky I–IV, Kinyaminsky I, II, and from a number of fortified and non-fortified settlements (Fedorova et al., 1991: 138; Semenova, 2001: 62, 65, 71, 72; 2008; Zykov, 2012: 206, fig. 67).

Various pendants are represented by only single finds, while tripartite arched and quatrefoil sewn decorations (Fig. 4, 4 , 5 , 9 , 10 ) were widely used for decoration. At Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV alone, 135 tripartite and 347 quatrefoil decorations have been found. These artifacts are also known from other sites of the Lower

Angara region, and appear in the burials at the mouth of the Koda River and the Chadobets River, as well as at Sergushkin-3, Otiko-1, Koda-2, Okunevka, and Ust-Kova sites (Leontiev, Ermolaev, 1992: 18; Privalikhin, Fokin, 2009: Fig. 5–11; Basova, 2010: 488; German, Leontiev, 2011: 383; Dolganov, 2011: 397; Berezin, 2002: 33; Tomilova et al., 2014: Fig. 2). Such objects were, in fact, the most common adornments in the 11th– 14th centuries in the Lower Angara region. Evidence for the production of such tripartite and quatrefoil sewn decorations in northwestern Siberia is attested to by the Tazovsky jewelry workshop (Khlobystin, Ovsyannikov, 1973). Judging by these objects, the flow of adornments from the northern regions of Western Siberia to the basin of the Lower Angara River appears to have been continual throughout the Late Middle Ages. At the same time, it cannot be ruled out that the simplest tripartite and quatrefoil plates might have been cast locally, in imitation of imported examples.

It should be expected that objects produced in the Angara region will also be discovered in the archaeological record of Western Siberia, but this will require additional research. At present, we may only point to an iron Y-shaped object, an accidental find from the locality of Barsova Gora (Chemyakin, 2008: Fig. 5, 8 ). Objects of this form, and of similar sizes, were widely used by the inhabitants of the Middle Siberian taiga region and may serve as an indicator of local material culture (Mandryka, 2006: 153). Other artifacts are typical both for the Lower Angara and the Lower Ob population, including, for example, end piece bow plates. These were made of antler, with a split base, and a cutout for the string on the end. Bows with similar plate attachments were widely used on the Angara and the Yenisei, and are also known from Western Siberian assemblages from the fortified settlements of Zelenaya

Gorka, Bukhta Nakhodka, and Yarte VI (Smirnov et al., 1957: 233; Kardash, 2011: 27; Plekhanov, 2014: Pl. 5, 29 ). Similar chisel-like arrowheads with extended spikes, and narrow comb/hairpins, dated to the Late Middle Ages have been found in the Angara and Lower Ob regions. The presence of identical household items in areas which are sufficiently distant from each other may be used to infer not only stable exchange ties, but also a certain cultural proximity of the populations inhabiting these regions.

Objects from the steppe, forest-steppe, and southtaiga regions of the West Siberian Plain (Altai, Novosibirsk region of the Ob, Baraba, Tomsk region of the Ob) also reached the Angara region. Such objects include openwork pendants of the “Srostki” type (Fig. 5, 2 ) found in burials at Koda-2 (Basova, 2016: 103, fig. 2, 5 ) and at Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV. D.G. Savinov pointed out that these adornments were typical of the Srostki culture of the 9th–10th centuries (1987: 88). Such pendants were likely parts of fasteners, and were widespread in the area between the Ob and Irtysh rivers and the adjacent territories in the 10th–12th centuries (Arslanova, 2013: 108). This category of objects includes a round wheel-shaped openwork pendant (Fig. 5, 1 ) from the burial ground of Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV, which is almost identical to the finds from the basins of the Middle Tara River (Kryuchnoye-6 burial ground) (Molodin et al., 2012:

86) and the Lower Tom River (Basandaika cemetery) (Basandaika, 1947: 28, 30). Another openwork pendant has parallels in the Tomsk region of the Ob (Fig. 5, 4 ).

Numerous parallels of similar two-part fasteners from the Lower Angara region (Fig. 5, 5 , 13 ) are known from the medieval materials of the Upper Irtysh region, the foothills of the Altai, the Tomsk and Novosibirsk Ob regions, and the Chulym region (Senotrusova, Mandryka, 2015). Spiral earrings (Fig. 5, 6 , 7 ) made of wire and rectangular in cross-section, which were found at Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV and in the burial at the Koda-2 site (Basova, 2016: Fig. 2), may also be attributed to southwestern Siberia. The same earrings appear in the 11th–12th century complexes from Berezovy Ostrov-1, in the Novosibirsk region of the Ob (Adamov, 2000: 59, fig. 108). The same group of finds includes large quatrefoil sewn plates with openwork “petals” (Fig. 5, 3 ). Similar objects are known from the Ilovka cemetery at the Chulym River, burial grounds at the mouth of the Malaya Kirgizka River, and the Tashara-Karyer-2, Sanatorny-1, and Osinka sites (Belikova, 1996: Fig. 102, 6 ; Pletneva, 1997: Fig. 163, 9 ; Savinov, Novikov, Roslyakov, 2008: 61, 167, fig. 34).

Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV has yielded elements of several belt sets similar to Western Siberian belt sets. These include ring-shaped, convex bronze overlays (Fig. 5, 18 ), which were attached to the belt using one or two iron rivets, and round silver overlays. Similar

Fig. 5 . Western Siberian bronze objects from Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV.

artifacts come from the burials of the late 11th to early 13th century at the Osinki burial ground in the Upper Ob region (Savinov, Novikov, Roslyakov, 2008: 61). Identical overlays are also known from the Middle Chulym region and the Altai from the burial ground of Teleutsky Vzvoz-1 dating to the Mongolian period (Belikova, 1996: Fig. 99, 25 ; Tishkin, Gorbunov, Kazakov, 2002: Fig. 39, 24–26 ), while bronze overlays are known from the Tashara-Karyer-2 cemetery in the Upper Ob region (Savinov, Novikov, Roslyakov, 2008: 317). The Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV collection contains miniature tripartite bronze belt overlays of various shapes (Fig. 5, 9 , 10 , 15–17 ), similar to those from Yelovka in the Upper Ob region (Matyushchenko, Startseva, 1970: Pl. VI), and miniature bronze wing-like overlays (Fig. 5, 8 ) similar to those from Kaltyshino I in the Kuznetsk Depression (Savinov, 1997: Fig. 7).

Finally, the Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV assemblage contains evidence of mediated cultural ties between the Lower Angara region and Volga Bulgaria. Heart-shaped belt decorations/overlays, and pentagonal belt tips with floral decorations were recovered from burial 50 (Fig. 5, 11 , 12 , 14 ). Such belt elements were widespread in the territory of the Volga Bulgaria and along the Kama trade route. The Bulgarian origin of the belt set is also confirmed by the analysis of the artifacts’ alloy composition (Gunenko, Senotrusova, 2013: 72). Another similar belt set is known in Siberia: it was found at the Kipa III burial ground in the taiga Irtysh region (Konikov, 1993: 36).

Conclusions

These data indicate that the people of the Lesosibirsk culture of the southern taiga in the Lower Angara region were enmeshed within a complex system of intercultural ties in antiquity. They maintained contacts with the population of the steppe regions throughout the entire Late Middle Ages, connections that reflect the involvement of northern peoples with the political interests of state entities that dominated the steppe belt of Eurasia at that time.

The influence of the Yenisei Kyrgyz people on the taiga population of Middle Siberia has been greatly exaggerated in the academic literature. Objects of the Tyukhtyak appearance are unknown on the Angara and Yenisei regions. We identified a small number of Kyrgyz objects, but only during the 11th–12th centuries. This likely reflects the formation of the Krasnoyarsk-Kansk variant of the Kyrgyz culture, when the Kyrgyz people migrating from Tuva to the north appropriated foreststeppe areas and had contacts with the taiga tribes (Savinov, 1989: 146). Evidence of a direct presence of these nomads on the banks of the Angara River has yet to be found, and not a single burial containing exclusively Kyrgyz objects is currently known. Apparently, the appropriation of the southern taiga territories was temporally restricted, and perhaps more formal than actual (Senotrusova, 2015).

Across history, much of the interest by pastoral nomads in the taiga regions was stimulated by their interest in obtaining furs, which were highly valued in the Middle Ages. In addition, during the Mongolian period, these “forest peoples” could be recruited into the army or the administrative apparatus of the Mongol Empire. This pattern is confirmed in the Angara archaeological record by the presence of prestigious objects, such as belt sets with plaque-like saber hooks in the southern taiga burial assemblages. Belt sets were objects of high social status, and signified social engagement with overarching structures (Kramarovsky, 2001: 67). The southern taiga zone of Middle Siberia was included into the orbit of political and cultural influence first of the Mongolian state, and somewhat later of the Yuan Dynasty. At the same time, this period seems to have witnessed few changes in the economic system or funeral rites; the traditional way of life continued to dominate among the population inhabiting the southern taiga region during the Late Middle Ages.

For many centuries, cultural ties between Middle and Western Siberia appear to have been continuous and resilient. The cultural proximity of ancient populations inhabiting these regions is supported not only by the occurrence of the common types of adornments made of non-ferrous metals, but also by the similarity of the ornamental décor on pottery of the Lesosibirsk style and Western Siberian vessels dating to the Late Middle Ages (Mandryka, Biryuleva, Senotrusova, 2013).

Generally, the burial assemblages from Prospikhinskaya Shivera IV and other burial complexes of the Lower Angara region reflect a wide range of intercultural ties linking the local population inhabiting this region with outside groups during the Late Middle Ages. These finds indicate that taiga inhabitants took an active part in the key historical and cultural developments that took place at this time across northern and central Eurasia.