Designing Digital Multimodal Resources for the Kindergarten: From Intuition to Awareness

Автор: Nikolay Tsankov, Milena Levunlieva

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.12, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The study adapts McNeill and Robin’s (2012) evaluation system for digital story design to identify pre-service kindergarten teachers’ perceptions of its process and product aspect. Conducted within the course Pedagogy of Construction and Technology, the empirical study involves self-, peer, and expert evaluation of custom-designed multimodal educational digital ensembles. Significant differences across these evaluation axes emerge in the indicators clarity and cohesion, the capacity of the resource to render symbolic/metaphorical meanings, and students’ consideration of the audience’s age-related capabilities. Unlike students, experts manifest a more pronounced criticism, because their evaluation draws on their experience and perception of the applicability of the resources. To contextualize the three axes of evaluation, focus group discussions were conducted exploring students’ intentions related to goal setting, preparation, the author’s presence, and the multimodal modes of expression. A lack of specialized technological knowledge was established for effective use of multimedia software. Inconsistencies in students’ perception of the storyboarding process were also identified, along with an orientation to the audience’s motivation rather than to their age-related characteristics. These findings highlight the need for a systematic design of university courses in educational multimodal digital design for Education majors.

Evaluation of multimodal digital resources for educational purposes, meaning-making as design, multimodal digital ensemble, pre-service kindergarten teachers’ training

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170206567

IDR: 170206567 | УДК: 373.24:004 37.091.3:004 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2024-12-3-657-667

Текст научной статьи Designing Digital Multimodal Resources for the Kindergarten: From Intuition to Awareness

While the theory of education since the New London Group has relied increasingly heavily on the synergic incorporation of modalities other than the verbal and the cognitive ones in the process of educational interaction, its practice is still catching up.

© 2024 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

evaluation, is intended to trace the strong and weak points in students’ design process and analyse the level of correspondence between the task set to the designers and the digital multi-modal assemblies they produced as a didactic instrument for pre-school children in order to help them design and construct a specific object as part of their work in the thematic area Construction and Technology.

Theoretical Rationale

The consistent association of teaching literacy with the teaching of multi-modal and digital literacies ever since New London Group’s groundbreaking work on literacy pedagogy requires continuous revisiting of national educational panels and poses specific curriculum design requirements on under-graduate, graduate, and post-graduate programs in Education. Pre-service teachers need systematic and dynamically oriented knowledge not only on how to appreciate and assess the multi-modal nature of learning, but also how to design and use multi-modal didactic instruments effectively with students at all educational and age levels.

In the context of “culturally and linguistically diverse and increasingly globalized societies”, The New London Group define two interdependent and mutually defining goals of literacy learning: (i) providing instruments to use and perceive effectively the ever changing “language of work, power and community” and (ii) forming, stimulating and fine-honing students’ “critical engagement to design their social futures and achieve … fulfilling employment” ( Cazden, Cope, Fairclough, Gee, Kalantzis, Kress, Luke, Luke, Michaels and Nakata, 1996:60 ).

Such goals result in a conception of meaning making as design that identifies meaning both as a process and as a product – a fundamental premise that allows educators to consider any semiotic activity, activating the tactile, audio, visual, gestural, spatial, spoken, and written modalities ( Kalantzis and Cope, 2012 ) in a non-hierarchical manner ( Bezemer and Kress, 2015 ; Magnusson and Godhe, 2019 ), as “an active and dynamic process, and not something governed by static rules” ( Cazden et al., 1996:60 ). It also incorporates all modalities in the learning process transforming literacy learning into acquisition and active application of multiliteracies in a continuous process of designing and reconceptualizing resources and meanings.

This conception of literacy pedagogy also implies that education majors, including those specializing in pre-school education, should possess the skills and capacities to design, create, and assess multimodal compositions as part of children’s preparation for school. It also suggests that literacy practices should ramify into the organization and implementation of small projects, experiential learning, effective use of materials to construct everyday objects, etc. All these activities are part of the Construction and Technology thematic area in kindergartens, which makes it especially suited as a medium and environment for meaning-centred multiliteracy learning.

In an exploration on “how digital competence is conceptualized in recent revisions in the curriculum for Swedish compulsory school”, Godhe, Magnusson and Hashemi (2020:74) identify four recurrent themes incorporating (i) the use of digital tools and media; (ii) programming; (iii) critical awareness and (iv) responsibility. However, they argue that the most pervasive theme emergent in all subject areas is “the tool-oriented use of digital tools and media” ( Godhe et al., 2020:74 ) – a tendency they find alarmingly limited in view of the international frameworks of digital and multi-modal competence and in the context of the increasingly multi-modal nature of communication nowadays.

The alert raised by Godhe et al. (2020) suggests that the operationalization of literacy as “literacy in multiple forms in a context of cultural diversity and of ubiquitous technology and multimedia in communication” ( Paniagua and Istance, 2018:129 ) also requires a transformation of instructional content and curricula in university Education programs – a transformation guided by the concept of teachers and learners as active designers of their knowledge, learning environment, and ultimately, their social futures.

These conclusions further consolidate the argument that “multiliteracy and critical literacy are not just related but inherent in all literacy engagement” (Silvers, Shorey and Crafton, 2010:379) – a conception which confirms the fundamental association between social engagement and literacy as a meaning making ability. Kalantzis and Cope (2008:203) define five questions to guide teachers when designing multimodal activities and resources for literacy learning: (i) what is the referential value of meanings (representational); (ii) how do meanings apply to one another (organizational); (iii) what is the relation between meanings and the persons they involve; (iv) what is the relative status of meanings within the larger world of meaning (contextual); (iv) whose interests are the meanings intended to support (ideological). Designed to respond to these five zones of semantic and operative density, and based on a “multiplicity of forms”, multimodal resources and analysis “lead to critical reflection and connection with everyday experiences” (Kalantzis and Cope, 2008:134).

In a reality where multimodality is the natural form of communication, new digital platforms and information tools are erasing the boundary between designers of meaning and their audiences, which is why young people are naturally inclined to analyse and produce multimodal texts ( Anderson, 2003 ).

Within the framework of teacher education, this means that special considerations need to be made for pre-service teacher training to be oriented towards the diverse and numerous ways of applying, designing and planning the goal-oriented, effective and adequate use of digital multimodal assemblies in pedagogical interaction. Jewitt (2009: 12) proves that multimodality exceeds the realm of theory and applies to a myriad of applications, regarded concurrently as “theory, perspective, field of research or methodological instrument.” Vasudevan, Schultz and Bateman emphasize the benefits of building literacy skills and providing conditions for engaged meaningful learning ( Vasudevan et al., 2010 ). Becker and Blell (2018:129) argue that students’ awareness of the authenticity of their target audience favours an enhanced understanding of new concepts and their application. Johnson and Smagorinski (2013) foreground the idea that the design of multimodal ensembles in language education increases contextual understanding and, alerting students to their target audience, captures the pragmatic function of language and improves social interaction. In an exploration of multimodal instruction in science education Demirbag and Gunel (2014) conclude that it enhances the quality of causal and critical thinking and the degree to which students master the instructional content.

Despite all these findings, evidence is accruing of sustained lack of access to high quality teaching to support 21 c. skills, which necessitates that teachers’ knowledge should be contextualized not only as pedagogy and content, but also in terms of technology ( Mishra and Koehler, 2006 ) and supported by a profound understanding of the multimodal nature of digital texts and environments ( Gregori-Signes, 2014 ; Kress, 2010 ) to provide conditions for future teachers to become skilled designers and composers of multimodal digital texts.

Building on this argument, Cappello (2019) demonstrates that a focus on a visual curriculum, including digital multimodal compositions, makes it possible for education majors to express their identities. Delving further into the essence of multimodal storytelling, Mills and Unsworth (2017:612) argue that “in visual narratives, characters are developed through emotional expressiveness, which is indicated largely through nuanced and authentic representations of body language, such as stance, gestures, facial expressions, and movement” ( Mills and Unsworth, 2017:612 ).

Exploring the effects of “immersing teacher candidates in a multimodal composing experience”, Shinas and Wen (2022:7) put forward compelling evidence of:

-

• intentionality of design choices;

-

• prominent expression of designers’ sociocultural identities in both the multimodal composition process and in the post-assignment reflections of students;

-

• developing awareness of teacher candidates of the benefits digital storytelling can bring to the literacy classroom in terms of creative skills and self expression;

-

• a changed perception of technology integration in education and in personal growth ( Shinas and Wen, 2022:8 ).

Table 1. Structural semantic, and functional components of the multimodal composition (based on Cazden et al. (1996) , Halliday and Matthiessen (2004) and Halliday and Matthiessen (2004))

|

PRODUCT ASPECT of the multimodal composition as part of the multimodal communication continuum Creative realization |

||

|

PROCESS ASPECT: Form (of expression) and Content (modes of meaning) |

FUNCTIONAL ASPECT: Conceptual core |

|

|

Pragmatic/Interpersonal (language as action or the audiences’ relationship with the author of the message and what it is intended to do) |

||

|

Representational (what the meanings refer to) |

Visual mode of meaning Language mode of meaning Audio mode of meaning Spatial mode of meaning Gestural mode of meaning |

|

|

Expressive (how the author/ designer and the meanings apply to each other) |

Ideational (language as reflection - the audiences’ experience of the outer world/the message reflected in its potential to activate response (social, emotional, creative, cognitive, empirical, etc.) |

|

|

Contextual (where do these meanings stand in relation to the larger world of meaning) |

Textual (enabling and organizing the ideational and interpersonal functions through the potential for synergy of meaning, knowledge and active experience |

|

Tracing back the historical development of the multimodal composition, G. Palmery demonstrates that the scope and content covered by the umbrella term multimodal text is not an evolutionary new idea ( Palmeri, 2012 ). The operationalization of its structure and components for the purposes of assessment, however, are a later development. Ball (2012:70) , editor of Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, whose mission is “to offer scholars a place to transfer their knowledge of linear, print-based, academic writing into multimedia-based scholarship that enacts the author’s argument”, summarizes the assessment criteria for scholarly multimedia (webtexts) introduced for the needs of the Institute for Multimedia Literacy (IML) honours program in Digital Writing Studies based on ( Kuhn, 2008 ) and revisited by Kuhn, Johnson and Lopez (2010) .

Elaborating on Kuhn’s criteria, she defines 6 rather than the original 4 components of multimodal texts: (i)conceptual core, (ii) form and content, (iii) creative realization, (iv) research component; (v) audience; and (vi) timelines. Table 1 visualizes our concept of the multimodal composition as a unity of form, content and function in which our adaptation of the assessment criteria suggested by Ball (2012) and McNeil and Robin (2012) is grounded.

Methodology

The empirical study was conducted with a sample of 32 under-graduate students of Pre-school and primary school pedagogy. As part of their course in Pedagogy of construction and technology activities. The course is oriented towards the design of methodological solutions for pedagogical interaction in the kindergarten which form and develop specific technological knowledge, skills, and attitudes closely related to children’s preparation for school. Within the frame of the area of Construction and technologies education it focuses on work with figures and visuals, understanding and solving problems, carrying out small projects, as well as on knowledge transfer and application of technological operations. The educational and psychological rationale behind the activities within this area includes providing conditions for self-realization through games, building children’s confidence in their capabilities, and stimulating their motivation.

The following assignment was given to the Pre-school education majors: Design a situated pedagogical interaction in the educational area “Construction and technologies” which allows for a constructionist and/or technological analysis in the condition of multimodal presentation of a construction and/or technological process. The project should combine a variety of modes of representation (visual – photos, illustrations, video, colours, symbols; audio – music; speech – speed, rhythm, meaningful pauses; speech; writing, space – movement, gestures, facial expressions).

The research is pre-eminently aimed at establishing the points of convergence and divergence in the assessment, self-assessment and expert assessment stage of the projects. It is based on McNeil and Robin and McNeil (2012) who propose an evaluation framework for digital storytelling that has three axes focusing on: the design process, the development process, and the completed product. Each of these is composed of: self- evaluation by the creator(s), peer-evaluation by other students, and educational evaluation by the teacher. We have adapted the criteria and indicators in the evaluation rubric to account for the fact that the evaluation is provided by pre-school teachers expert in the field of digital storytelling, who did not witness the design process and were only familiar with its result. Therefore, the evaluation in our adapted framework (Table 2) is focused on the product itself, rather than on the its design or development phases.

Table 2. Integrated evaluation framework for contextual assessment of multimodal designs

|

Criteria |

Expert/peer/self-evaluation Indicators |

Focus group discussion questions |

|

1. The aim is clearly stated and is in accord with: (Why?) |

|

|

|

2. Multimodal content of the story (What?) |

|

2. Describe the preparation stage of the design in view of its (i) setting; (ii) script; and (iii) objects and instrument used to demonstrate the instructions. How did you choose these objects? Did you use available ones or did you buy new ones, specifically for this purpose? How did you choose the mode of designing your digital resource in terms of software, hardware, device? |

|

3. Multimodal signature (personal presence) of the author (How 1) |

to the target audience (the potential participants in the communicative act) is easy to identify. |

3. During the preparation stage did you have specific expectations about your potential audience? Did these expectations affect your preparation? How? |

|

4. Multimodal means of expression (How 2) |

|

4. Which are the elements of your video which may elicit a strong emotional response from the children? Which are the elements of your video that may elicit a strong cognitive response? |

A self-assessment card was designed on the basis of the criteria and indicators pointed out on Table 1 and a cross examination was conducted of the data coming from three instruments: self-evaluation, peer evaluation and expert evaluation by teachers.

The expert evaluation method collects data stemming from the knowledge and experience of experts in the field of pre-school education (six experts with over 10 years of experience and with professional interests specifically oriented towards the design and adaptation of digital resources). These data are instrumental in analysing the degree to which students’ multimodal ensembles meet the criteria and indicators listed above.

The study employs the Delfy method to elicit independent expert evaluations and prognoses and the results are analysed by deducing the average of expert assessments in relation to each indicator. The method of heuristic prognostication is also applied to provide experts’ perspective on the potential of the multimodal ensembles for improvement and for reaching an adequate quality to be introduced to educational practice.

The focus group discussion method was employed to elicit information through focused questions by forming two groups of 12 students. The constructed semi-structured interview included the following subject areas as starting points: (1) descriptive goal-setting in the digital multimodal ensemble; (2) design, scripting, and composition of the digital multimodal ensemble; (3) technological solutions chosen for the digital multimodal ensemble; and (4) cognitive, social, and emotional methodological construction of the digital multimodal ensemble. In addition to eliciting information through focused questions, the discussions with the focus groups served as an additional point of departure for our analysis and provided us with the opportunity to formulate our hypothesis.

Results

The results of the self-evaluation, peer evaluation and expert evaluation of the multimodal digital ensembles are presented in Table 3 and only those will be commented which demonstrate the required level of statistical significance and differences.

Within the study, a statistically significant difference was found between the students’ self-evaluation (M = 8.25) regarding “the consideration of the target audience capcities” the expert evaluation (M = 6.35) of the same indicator. The results of Mann-Whitney U test showed that there was a statistically significant difference between the experts’ evaluation and the students’ self-evaluation Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) was 0.012, indicating that p = 0.012<0. 05, which is evidence of a statistically significant difference in the values and leads to the conclusion that there is a difference between the two groups (the students and the experts) in terms of what educational value the multimodal ensembles created by the students bring to the audience in view of their age-related capacities.

|

Table 3. Average evaluation results |

|||

|

Indicator |

Average selfevaluation ( M ) |

Average peer evaluation ( M ) |

Average expert evaluation ( M ) |

|

Allowances are made for the target audiences (age-related) capacities |

8.25 |

7.95 |

6.35 |

|

Adequacy of the multimodal (visual, verbal, audio) medium to the defined goal |

8.00 |

7.35 |

7.00 |

|

Speed of the multimodal ensemble (rhythm and voice punctuation |

7.25 |

8.95 |

8.00 |

|

The content creates and atmosphere corresponding to the educational goal |

9.05 |

9.00 |

7.85 |

|

The modes of representation use can convey symbolic/metaphorical and/or attitudes/intentions |

7.00 |

7.25 |

5.00 |

|

The modes of representation use can convey referential/logical meanings only |

8.25 |

8.15 |

7.05 |

|

The author sets a tone and atmosphere that correspond to the goal and the content of the ensemble |

9.00 |

8.75 |

7.25 |

|

The role of the author in the communicative act is clearly stated |

9.55 |

9.35 |

9.00 |

|

The attitude of the author to the other participants in the communicative act (the audience) is clear and visible |

9.35 |

9.15 |

8.95 |

|

Cohesiveness of the ensemble |

8.00 |

7.95 |

6.85 |

|

Cohesion of the ensemble |

7.55 |

7.00 |

5.25 |

|

Clarity of the message |

6.95 |

9.85 |

5.00 |

Statistically significant differences between the self-assessment and the expert assessment were also found with respect to the indicators “the modalities used (visual, verbal, sound) can convey symbolic/ metaphorical meanings and/or attitude/intention”, where Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) is 0.003 on the Mann-Whitney U test, “message/narrative integrity” where Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) is 0.011 on the Mann-Whitney U test, and “message logical coherence”, where Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) is 0.001 on the Mann-Whitney U test. In all three cases, it is evident that p < 0.05, which is evidence of a statistically significant difference in values and allows the conclusion that there is a difference between the two groups (of authors/students and experts) in terms of the indicators in the evaluation/self-evaluation of the multimodal ensembles created by the students.

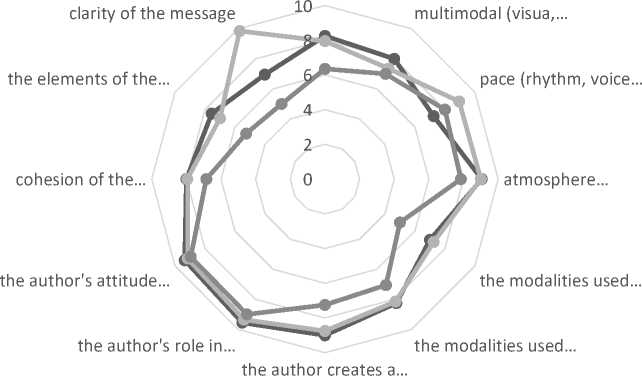

Overall, a comparative examination (Figure 1) of the students’ self-assessment, peer evaluation and expert evaluation highlights the experts’ more manifested criticism arguably based on their experi- ence and the search for practical dimensions of the application of the multimodal digital ensemble. The most sensitive divergence in the values occur in relation to: (i) the clarity of the message; (ii) the cohesion of the message; (iii) the capacity for the modes of representation used (visual, verbal, aural) to convey symbolic/metaphorical meanings and/or attitude/intent; and (iv) the author’s consideration of the audience’s (age-related) capacities.

Arguably, these differences could be easily attributed to the experts’ professional experience. As in-service teachers they inevitably assess the multimodal ensemble from the perspective of its application in kindergartens and its potential results. However, it is worth noting that the indicators cohesion and cohesiveness actually characterize any text in terms of its perception and generation and thus apply to any message, irrespective of whether it is preeminently verbal or includes other modalities. In this case cohesiveness characterizes the text in terms of its completeness – whether or not all the elements are present that make it comprehensible in favourable communicative conditions. The cohesion indicator, in its turn, applies to the congruence among the separate meaningful element and their representations (here they include the visual, audio, spatial, verbal, ets. modes) on the one hand, and the course of the multimodal ensemble, on the other, which develops in space and time as a story. As designers of these stories the students have the prerogative to be familiar with the process of meaning-making and its immediate context – an opportunity the experts are denuded of. In their assessment, they substitute this actual context of activating and re-designing the available resources for a heuristic prognosis of the potential communicative situations and social practices where this product can be used. In this sense, their assessment emphasizes and foregrounds the multimodal ensemble preeminently as a resource, but not as a process. The students, on their part are mostly oriented towards the decisions and choices made during the design process.

Figure 1. Comparative analysis: self-evaluation, peer evaluation, expert evaluation results

Comparative anaysis

—•— Sef-evaluation (M) —•— Peer evaluation (M) —•— Expert evaluation (M)

audience's capacities

It is precisely this difference of focus inherent in the roles of the evaluator and the author/designer as part of the meaning-making process that also accounts for the discrepancies in the section concerning whether or not the multimodal ensembles make considerations for the abilities and special characteristics of the target audience. Along with their assessment of the multimodal medium of the communicative act, to the experts this indicator is of crucial importance in assessing then goal component of the multimodal resource as a didactic instrument. To the students on the other hand, whose target audience is the child in the kindergarten but only as part of the project assigned to them by their lecturer, this indicator also reflects their perception of the resource as a solution to a task given.

The awareness of this double addressing of the multimodal ensemble also lies at the basis of our persuasion that our quantitative data should be analysed only using the information received during the focus-group discussions as a key or password for their interpretation.

Discussions

Our interpretation of these results is rooted in the perception that any exploration of how we communicate through a variety of modalities should take as its starting point how language, gesture, image, space and sound are used in situated activities: “Meaning-making is always relative to social practices. What is a relevant way of perceiving an image cannot be decided upon unless one considers the practice of which it is a part. All representations have meaning potential, but what aspects of these potentials are exploited is a situated affair” ( Ivarsson, Linderoth and Saljo, 2009:210 ).

Since our focus is on the evaluation and perception of the multimodal ensembles as a data mining opportunity for designing Digital storytelling courses for education majors, we take as our point of departure the changing social and communicative roles of the participants in the three distinct, yet interrelated, assessment processes: peer evaluation, expert evaluation, and self-evaluation, which was conducted in two complementary stages - through semi-structured interviews and questionnaires.

Our data is analysed and explored through the lens of the information we received from our focus group discussions with students about (i) the design process and the script in view of students’ goals, (ii) the preparation process in terms of timing, technological solutions, software, hardware, materials used, etc.; (iii) designers’ expectations and considerations of the target audience; (iv) elements of the ensemble specifically aimed at emotional and cognitive response.

The recurrent themes during the interviews gave us the base-line for our investigation into the other data coming from the evaluation rubrics. We coded the transcriptions using a process of independent coding to increase reliability.

Several important areas of designers’ perception of their product emerge from students’ answers. In terms of its goal aspect what they find crucial is the instructional content as its main determinant and its accordance with the expected outcomes for the audience. Students also consider vital the clarity of the description of the process presented in the video in terms of two main factors: its separate stages and the quality of the video as a demonstration of the steps the audience is to take in constructing an object. Students also believe that the goal aspect of their product is also informed by the right combination of different modes of representation, such as (i) the amalgamation of speech, demonstration/gesture, posture, and visibility; (ii) the right combination of sound elements (balance, rhythm); (iii) the visibility of the objects and the suitable tools used to demonstrate the construction process; (iv) the synchronization between sound pauses and their duration in relation to importance/difficulty level of the element being highlighted; (v) the correct movement in space; (vi) the correct and concise articulation of instructions so as to demonstrate the sequence of operations by combining explanation and display. Additionally, preservice kindergarten teachers include the allowances made for the audience’s age-related capacities as part of the content aspect of the video such as rendering the essence of the message in a way that the children would pay attention and understand what was important. However, this consideration does not actually address the goal aspect of the resource designed. Another component of the goal aspect of the multimodal ensemble seems to be students’ resources and technical considerations, which include using a teacher’s book to follow a precise sequence of technological operations to create the story; using a phone to record the video and improving its quality so that the result is more holistic; estimating the correct distance between the camera and the staging. No reference to specific software products for creation of digital content was made during the discussions.

As to students’ perception of the preparation process and its most important highlights, these include content and script, form, and the presumed stages of the digital story. In terms of content students find it important to tie their concept of what the children already know and have experience of to the subject matter and the script, to include a personal story in the narrative to impress the children and increase their focus; and to make a meaningful transition from the sensory to the emotional and the cognitive within the multimodal narrative. Their perception of the formal aspect of the ensemble involves matching the timelines of the separate components; combining a variety of multimodal modes (speaking, movement, gesture, display) into an overall composition; contrasting the colours in the materials/objects used to make every element as visible as possible; using a warm voice and making sure the quality of the video helps convey the message). The designers’ view of the stages of the multimodal narrative incorporates a preparation stage which covers decisions on the selection of didactic resources, developing a digital story plan; splitting the story into components of similar duration and combining them in an effective manner; deciding on the modes of representation that could be effectively combined.

The most informative panel in the discussion concerned the potential of the video to render emotional and/or cognitive import. Surprisingly, students did not leave that part to technology and vision. Rather, they perceive their own presence, personality qualities and ability to motivate the audience as the most important carrier of emotional and cognitive import in the multimodal design. Their most common answers here included simple and concise words so as not to make the demonstration difficult for the children; the accompanying music; the expressive and emotional speaking and the clear diction and slow pace of speech.

Conclusions

Based on the three-stage evaluation and focus group discussions as data mining opportunities for the design of practice-based courses on designing digital content for education majors, the following problem areas can be identified as starting points for targeted and systematic training in the creation of multimodal digital resources: (1) lack of specialized technological knowledge and skills in using software tools and platforms for creating multimodal digital narratives (e.g., Storybird, Adobe Spark, WeVideo), as well as insufficient skills in working with multimedia content such as video, audio, images, and text; (2) intuitive knowledge in the area of story composition of multimodal digital ensembles for educational purposes resulting in insufficient awareness of multimodal communication; (3) recorded inconsistencies in the processes of goal setting in and through digital multimodal ensembles, especially in view of what the designers want to achieve with their digital narrative - convey specific knowledge, develop particular skills or stimulate interest in a topic in the users of digital their narratives.

Clearly, the focus group discussions highlight the need for preparation in goal formulation, which can be successfully achieved by applying SMART goal formulation criteria in the design, planning and implementation of multimodal digital ensembles in an educational setting: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound.

Students participating in the study stated that their main guiding questions in creating the multimodal educational resource were: What is the main theme of the narrative? What knowledge and skills should children acquire? What is the specific age group of the audience? How can a script and storyboard be created so as to include the main points that need to be covered according to state educational content standards?

None of the study participants shared seeking feedback and reviewing or discussing the plan with colleagues and educators to make sure the goal was clear and achievable. The students also failed to plan, as part of their project implementation, methods to evaluate the effectiveness of their digital resources as an educational tool and to reflect on the process of creating and implementing their multimodal educational resource so as to identify strengths and weaknesses.

These inconsistencies, coupled with students’ insufficient concern with the audience’s level of knowledge, interests and preferences, imply that it is much more efficient and effective to design courses in creating digital content for education majors starting from their own perceptions and using these as points of departure to address the weaknesses in their mostly intuitive designs by bringing more awareness and digital literacy to the process. Undoubtedly, digital literacy standards can help the design of such a course, but the real point of departure is the exploration of students’ own idea of what a digital story should be like and what it could do. The three-stage evaluation adapted to the needs of pre-school teachers, along with focus group discussions with students prior to organizing follow-up targeted trainings on creating digital multimodal educational resources can provide deep insights and valuable recommendations to help improve the creation and use of such resources. It is important to consider these highlights when planning and developing future research and education initiatives.

Acknowledgements

This study is financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, in the frames of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, first pillar “Innovative Bulgaria”, through the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science (MES), Project № BG-RRP-2.004-0006-C02 “Development of research and innovation at Trakia University in service of health and sustainable well-being”, subproject “Digital technologies and artificial intelligence for multimodal learning – a transgressive educational perspective for pedagogical specialists” № Н001-2023.47/23.01.2024.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.T., M.L.; methodology, N.T.; formal analysis, N.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.T. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Список литературы Designing Digital Multimodal Resources for the Kindergarten: From Intuition to Awareness

- Anderson, D. (2003). Prosumer approaches to new media composition: Consumption and production in continuum. Kairos, A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology & Pedagogy, 8(1). Available at http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/8.1/. Accessed 10 October 2022.

- Ball, C. E. (2012). Assessing scholarly multimedia: A rhetorical genre studies approach. Technical Communication Quarterly, 21(1), 61-77. http://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2012.626390 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2012.626390

- Becker, C., & Blell, G. (2018). Multimedia narratives – digital storytelling and multiliteracies. International Journal of English Studies, 29(1), 129-143. https://angl.winter-verlag.de/article/angl/2018/1/11

- Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2015). Multimodality, learning and communication: A social semiotic frame. Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315687537

- Cappello, M. (2019). Reflections of identity in multimodal projects: teacher education in the Pacific. Issues in Teacher Education, 28(1), 6–20.

- Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., Gee, J., Kalantzis, M., Kress, G., ... & Nakata, M. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard educational review, 66(1), 60-92. http://vassarliteracy.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/9012261/Pedagogy%20of%20Multiliteracies_New%20London%20Group.pdf DOI: https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

- Demirbag, M., & Gunel, M. (2014). Integrating Argument-Based Science Inquiry with Modal Representations: Impact on Science Achievement, Argumentation, and Writing Skills. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 14(1), 386-391. https://acikerisim.uludag.edu.tr/server/api/core/bitstreams/f76f65a6-af96-4f37-af4b-2e4ab8020477/content

- Godhe, A. L., Magnusson, P., & Hashemi, S. S. (2020). Adequate digital competence: Exploring revisions in the Swedish national curriculum. Educare, (2), 74-91. http://doi.org/10.24834/educare.2020.2.4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24834/educare.2020.2.4

- Gregori-Signes, C. (2014). Digital storytelling and multimodal literacy in education. Porta Linguarum (22), 237–250. DOI: https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.53745

- Halliday, M. A. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar (3rd ed). London: Routledge.

- Ivarsson, J., Linderoth, J., & Säljö, R. (2009). Representations in practices. A socio-cultural approach to multimodality in reasoning. In C Jewitt (ed). Routlage handbook of multimodal analysis. London: Routledge.

- Jewitt, C. (Ed.). (2009). The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (p. 340). London: Routledge.

- Johnson, L. L., & Smagorinsky, P. (2014). Writing remixed: Mapping the multimodal composition of one preservice English Education teacher. In Exploring multimodal composition and digital writing (263-281). IGI Global. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-4345-1.ch016

- Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2008). Language education and multiliteracies. In S May & NH Nornberger (eds). Encyclopedia of language and education (Vol. 1). Language policy and political issues in education. Boston: Springer Science.

- Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Chan, E., & Dalley-Trim, L. (2012). Literacies Cambridge University Press. New York. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139196581

- Kress, G. (2009). Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routlage. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203970034

- Kuhn, V. (2008). The components of scholarly multimedia. From gallery to webtext [Webtext compilation]. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 12(3). http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/12.3/topoi/gallery/index.html. Accessed 10 October 2022.

- Kuhn, V., Johnson, D. J., & Lopez, D. (2010). Speaking with students: Profiles in digital pedagogy. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 14(2). http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/14.2/interviews/kuhn/index.html. Accessed 10 October 2022.

- Magnusson, P., & Godhe, A. L. (2019). Multimodality in language education: Implications for teaching. Designs for learning, 11(1), 127-137. https://doi.org/10.16993/dfl.127 DOI: https://doi.org/10.16993/dfl.127

- Mills, K. A., & Unsworth, L. (2018). iP ad animations: powerful multimodal practices for adolescent literacy and emotional language. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 61(6), 609-620. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.717 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.717

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers college record, 108(6), 1017-1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810610800610

- Palmeri, J. (2012). Remixing composition: A history of multimodal writing pedagogy. SIU Press.

- Paniagua, A., & Istance, D. (2018). Teachers as Designers of Learning Environments: The Importance of Innovative Pedagogies. ducational Research and Innovation, 17-42, Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264085374-en DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085374-en

- Shinas, V. H., & Wen, H. (2022). Preparing teacher candidates to implement digital storytelling. Computers and Education Open, 3, 100079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2022.100079 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2022.100079

- Silvers, P., Shorey, M., & Crafton, L. (2010). Critical literacy in a primary multiliteracies classroom: The hurricane group. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 10(4), 379-409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798410382354 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798410382354

- Vasudevan, L., Schultz, K., & Bateman, J. (2010). Rethinking composing in a digital age: Authoring literate identities through multimodal storytelling. Written communication, 27(4), 442-468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088310378217 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088310378217