Developing strategy of wine festival promotion

Автор: Malygina Olga A., Belyakova Natalia Yu., Kvitko Irina B.

Журнал: Современные проблемы сервиса и туризма @spst

Рубрика: Региональные проблемы развития туристского сервиса

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.17, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The purpose of this paper is to determine how wine festival criteria impact on their promotion, and to develop practical recommendations and a strategy for wine festivals both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Design/methodology/approach - Qualitative data from 29 wine festival websites were gathered. Content analysis was used to establish criteria that affect promotion of wine festivals. Crosstabs were used to check whether established wine festival criteria affect a festival’s decision to disclose a participating wineries list as part of a marketing effort. The Alignment Squared model was used to draw up recommendations for organizing wine festivals during the COVID19 pandemic. Findings - Neutral, positive and negative criteria that have an impact on promotion of wine festivals were determined and practical recommendations were suggested on how wine festivals could benefit from these criteria. The connections between the general running time of wine festivals and their all-year-round marketing circle were studied. The statistical connection between wine festival criteria and its tendency to practice cross-marketing with participating wineries were examined. Originality - Recent studies do not consider and systematize the strategies for wine festival promotion. The criteria described in this study may be used as a basis for a comprehensive classification of wine festivals and bring valuable insights into organization of wine festivals around the world, while practical recommendations may be used as a guideline for organizers of wine festivals after the COVID-19 pandemic and if world crises like this ever happen again.

Wine festival, promotion strategy, place branding, event management

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140299804

IDR: 140299804 | УДК: 338.48 | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7979767

Текст научной статьи Developing strategy of wine festival promotion

To view a copy of this license, visit

Over the past decade, only a few studies have been conducted to analyze promotion strategies for wine festivals. However, the ‘event’ has become one of the central concepts in place branding theories and several scholars suggested ways of classifying events (Getz, 2008; Getz and Page, 2016; Mariani and Giorgio, 2017; Cieślikowski, 2016), but none of these classifications was based on event promotion.

Place attachment of wine festivals is one of the most important factors, that establishes an essential emotional connection with consumers making them willing to revisit a specific place (Davis, 2017; Ramkissoon et al., 2013). Even though event promotion has been extensively studied, none of the research implies that event branding should be studied together with place branding and place marketing concepts.

Building up a promotion strategy for wine festivals is extremely important for turning a wine festival at a local fair into an individual event that would be part of the regional strategy in order to increase the number of tourists and the worldwide visibility of the region. Applying the place branding concept to wine festival promotion will help analyze the visitors from a new perspective and consider new visitor attraction factors.

At the same time, the current COVID-19 situation obviously states that wine festival promotion combined with place branding could be massively used only after the crisis has been resolved. Therefore, the benefits of wine festival promotion are transformed into new practical recommendations aimed at resolving current issues with wine festivals.

The purpose of this study is to determine a promotion strategy for wine festivals through an analysis of the criteria that have an impact on wine festival promotion and to develop recommendations for wine festivals applicable in regular time and during the COVID-19 pandemic. To fulfil the purpose of this research, the following questions must be addressed:

-

(1) What criteria affect the extent of wine festival promotion?

-

(2) What criteria affect festival’s decision to make public a participating wineries list?

-

(3) Are the years of wine festivals significant for festival promotion?

-

(4) In what ways can these criteria help organize wine festivals in usual time and during the COVID-19 pandemic?

The questions above were assessed using the qualitative data from 29 wine festival websites using the content analysis method. The Alignment Squared model was applied to draw up recommendations.

This section is followed by the Literature Review with the emphasis on such concepts as place branding, events, wine tourism, and festivals. The Methodology Section provides details on the methods applied and research data, while the Results Section provides a research analysis. In the Discussion Section, the wine festival strategy and recommendations for wine festival organizations are provided as well as limitations and future research directions are discussed. The Discussion Section is followed by the conclusion.

Literature Review

Vuignier (2017) provides a systematic classification of the studies based on various approaches to defining the sphere of place branding: general concept of place branding (Zenker and Braun, 2010), place brands creating processes, target audience, communication campaigns and place perceptions (Vuignier, 2017), place marketing including promotion, urban issues, infrastructure and architecture (Parker et al., 2015). Notably, more than a third of the research papers include an analysis of individual case studies using practical tools, which makes them useful, but hardly comparable with each other (Vuignier, 2017).

Potential future research areas include identification of overall outcomes of place branding and place marketing when all the effort and resources are effective in terms of attracting and retaining visitors, tourists, and businesses (Cleave et al., 2016; Bose et al., 2016; Mabillard and Vuignier, 2017).

The phenomenon of “Place attachment” was introduced as a crucial factor in terms of festival’s characteristics, emotional engagement, and visitors’ intentions to revisit the place (Yolal, 2016; Davis, 2017; Zhang et al., 2019; Brownett and Evans, 2019). According to Davis (2017), the place identity and place attachment have an incredible impact on tourists' perceptions of the place, while Ramkissoon et al. (2013) believe that place attachment should be accepted as a starting point of attendees’ exploration of the environment. In his research paper, Davis (2017) approves that place attachment and identity help create an emotional connection between a visitor and the environment.

Event tourism

Getz (2010) defines event tourism as systematic planning and development of events as tourist attractions, including benefits to place marketing and image-making. Later Getz and Page (2016) came to a conclusion that event tourism should be considered as ‘an applied field devoted to understanding and improving tourism through events’.

Tourism events are seen as key and strategic products that provide several benefits to destinations (Teixeir et al., 2019; Getz and Page, 2016), such as enhancement of the destination brand and place promotion (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018; Richards, 2017; Getz and Page, 2016; Coghlan et al., 2017; Mariani and Giorgio, 2017; Mainolfi and Marino, 2018; Todd et al., 2017), improvement of the destination marketing strategy (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018), an economic impact (Coghlan et al., 2017), an increase in the popularity and competitiveness of the destination (Higgins-Desbi-olles, 2018; Getz and Page, 2016; Mariani and Giorgio, 2017), improvement of knowledge about the destination and local culture (Mainolfi and Marino, 2018), solving the problem of seasonality and developing urban infrastructure (Getz and Page, 2016). In total, events are seen as an opportunity to maximize all the benefits for all stakeholders (Richards, 2017). Mostly, these outcomes highlight that destinations are building strategies and developing a more integrated approach to all events that are taking place (Ziakis, 2013).

Indeed, numerous researches analyze the role of events in placemaking (Coghlan et al., 2017; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018; Richards, 2017). Some authors even argue that the benefits that events bring to a place is a more well-studied area than is the benefits that the place brings to events (Coghlan et al., 2017), other scholars highlight the interconnection between three elements – event, place, and tourism experience (Mariani and Giorgio, 2017).

However, much of these studies are focused on all types of events with little or no attention to wine festivals as a specific type of events.

Wine tourism goes along with food tourism both of which are popular among people with high purchasing power, medium or high level of education and income who are willing to feel the pure experience of special tourist services (Brown and Getz, 2006; Carra et al., 2016).

Wine tourism is more than just visiting wineries, vineyards, wine festivals, and wine shows at wine destinations (Thanh and Kirova, 2018), it also includes experiencing local culture (Marzo-Navarro and Pedraja-Iglesias, 2010).

This paper is focused specifically on wine festivals because of the core meaning of a wine festival and essential benefits it may bring.

A wine festival can be defined as a special event of a limited duration with the main focus on destination cultural resource – wine (Lee et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2005). Wine festivals are believed to be important tourist events due to their valuable role in attracting tourists (Kim et al., 2010). Wine festivals help create crucial opportunities, such as providing exclusive experience to taste local foods (Smith and Costello, 2009; Van Niekerk, 2014), promotion of local culinary products (Lee et al., 2017), development of local communities (Dodd et al., 2006; Velikova et al., 2017), increasing destination awareness and attractiveness (Lee et al., 2017; Dodd et al., 2006), appreciation of destination influencing destination and festival attendee loyalty (Çela et al., 2007; Woosnam et al., 2009; Lee et al.,

2017), increasing the competitive advantage of the destination (Lee and Arcodia, 2011; Kim et al., 2008) and providing economic effect (Kim et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2017).

Despite these critical factors, wine festivals were mostly studied from the perspective of visitor satisfaction (Chang and Yuan, 2011; Sohn and Yuan, 2013; Björk and Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2014; Viljoen et al., 2017) and none of the research addresses wine festival promotion.

Events classification

Only a few approaches to event classification are well-developed. The most common was introduced by Getz (2008, p.407) and has been studied in detail. Moreover, Getz’s classification is based on the categories of planned events (2008, p. 404). Cieślikowski (2016, pp. 21–22) also tried to develop a classification of festivals using all possible criteria.

Nevertheless, none of the existing classifications includes the type of event promotion. That is why we decided to suggest a classification based on wine festivals.

Overall, little research of wine festivals was done, even though the place branding theory is very useful in terms of events. That is the reason why this study is focused on wine festival promotion and development of strategy and classification based on wine festivals.

The role of winery’s brand in wine tourism

Although wine, a winery, and a wine region are focal elements in wine tourism, wine festivals may attract people who would never be ascribed into the category of wine tourists since they would not visit any winery or wine region on purpose. Nevertheless, the majority of visitors come to the festivals willing to gain wine-related experiences, subsequently, wine is an integral part of any wine festival (Yuan, J.J., Cai, L.A., Morrison, A.M. and Linton, S., 2005).

Methodology

The database consists of 900 wine festivals worldwide. These are all wine festivals that could be found on the Internet. According to statistics, from the general population of 900 wine festivals with a 90%-confidence probability and the confidence interval of +/– 15%, the current sample should consist of 29 wine festivals. We randomly selected 29 out of 900 wine festivals.

Our hypothesis was that the promotion strategy for wine festivals depends on how many years the festival has been organized. Several hypotheses are used to determine the festival’s age: the most recent is the study of rural festivals (Hjalager and Kwiatkowski, 2018) as in many countries wine festivals are organized in rural areas around specific wineries. Moreover, 15% of all studied festivals in the article had were dedicated to food and gastronomy that is the closest mentioning of these types of festivals in the literature. Hjalager and Kwiatkowski (2018) argued that newly established festivals are those that have been organized since 2000 and that older festivals are those that were launched before 1980. We slightly extended the limits to from three age groups:

-

• young – less than 25 years;

-

• medium – 25 to 50 years;

-

• old – more than 50 years.

The grouping 29 wine festivals by the age is presented in Table 1. The next step is the distributing wine festivals by countries. The leaders are France (6), Italy (5), USA (5) and Canada (2). The group of countries with 1 festival includes Spain, Cyprus, Hungary, Germany, New Zealand, Slovenia, Israel, Austria, Armenia, Australia, and Moldova.

All the festivals is also grouped by duration in terms of years, available services, number of visitors, visitors’ categories (local, international, both), involvement of other businesses, benefits delivered to destinations, activity on social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram), other events going along with the festivals, and several others. The content analysis is aimed at identification the impact of these on wine festival promotion and defined as neutral, positive, and negative. Overall, the wine festivals were classified based on these criteria.

It was also assumed that the majority of wine festivals would publicly release their lists of participants to gain cross-marketing advantages. Combining the brands of participating wineries and brands of festivals could be used as a cross-marketing tool aimed at maximizing mutual benefits for both festivals and wineries, including increasing consumer interest and attendance, revenue, an increase in brand awareness and recognition levels, a boost in credibility and loyalty, and a development of long-lasting relationships between festivals and a wineries.

To determine if there was any connection between a festival’s decision to publish an exhibitor’s list and the other criteria evaluated in this research, and how strong this connection was, statistical data about evaluated festival parameters was analyzed. A review of festival websites and social media was conducted in order to see if the festivals published participant lists.

Table 1 — World wine festivals

|

№ |

Festival’s name |

Country |

|

Young festivals |

||

|

1 |

Nantucket Wine & Food Festival |

USA |

|

2 |

Bordeaux Fête le Vin |

France |

|

3 |

National Wine Day in Moldova |

Moldova |

|

4 |

Tasting Australia |

Australia |

|

5 |

Yerevan Wine Days |

Armenia |

|

6 |

Vienna Wine Fest |

Austria |

|

7 |

Jerusalem Wine Festival |

Israel |

|

8 |

The Old Vine Festival |

Slovenia |

|

9 |

Habits de Lumière Epernay |

France |

|

10 |

Ardesio DiVino |

Italy |

|

Middle festivals |

||

|

11 |

Vancouver International Wine Festival |

Canada |

|

12 |

Sonoma County Harvest Fair |

USA |

|

13 |

New Orleans Wine and Food Experience |

USA |

|

14 |

Boston Wine Festival |

USA |

|

15 |

International Pinot Noir Celebration |

USA |

|

16 |

Le Marathon des Chateaux du Medoc |

France |

|

17 |

Marlborough Wine & |

New |

|

Food Festival |

Zealand |

|

|

18 |

Rheingau Wine Festival |

Germany |

|

19 |

Budapest Wine Festival |

Hungary |

|

20 |

Millésime Bio |

France |

|

Old festivals |

||

|

21 |

Niagara Grape & Wine |

Canada |

|

22 |

Grape Harvest Festival |

France |

|

23 |

Vinitaly |

Italy |

|

24 |

Limassol Wine Festival |

Cyprus |

|

25 |

Conegliano Valdobbiadene Festival |

Italy |

|

26 |

FestiVini Saumur-Champigny |

France |

|

27 |

Chianti Classico Expo |

Italy |

|

28 |

Haro Wine Festival |

Spain |

|

29 |

Festa dell’Uva |

Italy |

Festival websites and social media were analyzed in order to inspect if the festivals published participants lists. The calculations were performed via IBM SPSS Statistics software that is widely used for processing statistical operations. Crosstabs were used to reveal statistical connections and degree of power between variables (age of a festival, number of followers on social media, or grade of a festival) and disclosing a list of festival’s participants.

Table 2 — Mentioning of participating wineries in wine festival programme

Old World

|

France |

Bordeaux Fête le Vin |

No |

|

Habits de Lumière Epernay |

Yes |

|

|

Le Marathon des Chateaux du Medoc |

No |

|

|

Millésime Bio |

No |

|

|

Grape Harvest Festival |

No |

|

|

FestiVini Saumur-Champigny |

No |

|

|

Italy |

Ardesio DiVino |

Yes |

|

Vinitaly |

Yes |

|

|

Conegliano Valdobbiadene Festival |

Yes |

|

|

Chianti Classico Expo |

Yes |

|

|

Festa dell’Uva |

No |

|

|

Spain |

Haro Wine Festival |

No |

|

Hungary |

Budapest Wine Festival |

No |

|

Cyprus |

Limassol Wine Festival |

No |

|

Slovenia |

The Old Vine Festival |

No |

|

Austria |

Vienna Wine Fest |

No |

|

Germany |

Rheingau Wine Festival |

No |

|

Moldova |

National Wine Day in Moldova |

Yes |

|

Israel |

Jerusalem Wine Festival |

No |

|

Armenia |

Yerevan Wine Days |

No |

New World

|

USA |

Nantucket Wine & Food Festival |

Yes |

|

Sonoma County Harvest Fair |

Yes |

|

|

New Orleans Wine and Food Experience |

Yes |

|

|

Boston Wine Festival |

Yes |

|

|

International Pinot Noir Celebration |

Yes |

|

|

Canada |

Vancouver International Wine Festival |

Yes |

|

Niagara Grape & Wine |

Yes |

|

|

Australia |

Tasting Australia |

Yes |

|

New Zealand |

Marlborough Wine & Food Festival |

No |

There are four types of scales used for different types of variables: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio. In the case of the nominal scale, objects are classified into categories, for example, a regions of a festival or a fact of making the participant list public. On the ordinal scale, objects are grouped by categories sorted in relative order, for instance, the festival’s age (young, medium, old). Variability analysis using this type of scale is more sensitive than that using a nominal scale. The last option presented in IBM SPSS Statistics names ‘scale’, provide the option of proceeding with numeric data on an interval or ratio scale, for example, the number of followers on social media. Using the Chi-Square method and Cramer's V measure, the significance levels of the variabilities were evaluated.

Results

Several factors of wine festivals were defined by an extensive analysis.

The most frequent services during festivals are wine and food tasting, concerts, shows, and theatre performances. Worthmentioning examples include Marathons of Le Marathon des Chateaux du Medoc, Tasting Australia, the Grape Harvest Festival, and the Boston Wine Festival.

Several festivals choose a special historic location – historic center or place of interest (castle or museum): three young festivals (Ar-desio DiVino, the Jerusalem Wine Festival, the Vienna Wine Fest) and two more – the Budapest Wine Festival, the Grape Harvest Festival. This proves young wine festivals choose famous and popular tourist locations to stand out.

Mostly festivals attract both local and international tourists, however, in total, nine festivals work with local audience, but the distribution across age groups is similar.

Availability of the upcoming event dates is an interesting criterion. It was analyzed before the spread of COVID-19. All festivals from the middle group announced the dates for the next period, while three young festivals and four old festivals did not. The Haro Wine Festival, an old festival, easily solved this problem as the event is always held at on same date. We believe that the degree of festival promotion depends on the availability of the dates of the upcoming event because it helps from the point of view of promotion and marketing strategies. However, these details changed after the COVID-19 spread and most events were rescheduled.

The number of festival visitors is a tricky factor because many organizations do not publish real numbers, that is why for some festivals the data is impossible to find. Therefore, from our point of view this criterion cannot be used for classification. Overall, every category includes two or three festivals for which no information about visitors was found. The distributions of visitors are:

-

• young – 4,000–100,000 visitors;

-

• middle – 2,000–44,000 visitors;

-

• old – 4,500–125,000 visitors.

Festival promotion criteria

In terms of promotion strategies, several group factors with positive or negative impact could be defined.

Collaboration with other businesses & events . The inclusion of other businesses into the festival is an obvious factor of using all possible promotion resources. Surprisingly, the younger festival is, the more collaboration with other businesses it builds – nine out of ten young festivals are involved in collaborations vs only six middle and five old festivals.

The most popular partnerships are in music, other prevalent industries include food, local food producers, accommodation, dancing, and arts. Young festivals add special businesses such as shipping, charity organizations, airlines, museums and supermarkets. Aside goes festivals building alliances with government and local administration or with touristic agencies.

Collaboration with other events is also one of the weighty factors in terms of festival promotion. In total, there are eight festivals that choose this strategy and they can be divided into those which collaborate with international events and with local events. Festivals collaborating with international events hold the same festival in other countries (Bordeaux Fête le Vin, Vinitaly), organize cruises to other wine regions (Vancouver International Wine Festival) or event programs with twin towns (Rheingau Wine Festival). Festivals collaborating with local events are events that are developed under one brand. Usually nonprofit, governmental, or administrative organization proposes several events in the region by one brand (Conegliano Valdobbiadene Festival, FestiVini Saumur-Champigny, Tasting Australia, The Old Vine Festival).

Surrounding infrastructure development. As for festivals developing infrastructure, The Old Vine Festival brings local and international visitors to the city of Maribor, Slovenia, with the population of less than 100 people. Another impressive example is a small city of Haro in Spain with the population of 12 thousand people and 15 thousand visitors coming every year, thus contributing to the development of the region. The more valuable numbers were presented only by the Vancouver International Wine Festival that since 1979 has raised $9.5 million for the performing arts in Vancouver. It should be accounted as one of the important factors for festivals promotion.

“Selling” attitude. The events that are proposed only as trade fairs not aimed at forming single regional brand strategy come from young (Yerevan Wine Days, Vienna Wine Fest, Ardesio diVino) and middle (Millésime Bio, Sonoma County Harvest Fair) groups.

Local scale of event. Several local festivals attract mostly local visitors and do not improve the regional strategy of a destination (National Wine Day in Moldova, Limassol Wine Festival).

Activity on social media. In March 2020, we monitored festival pages on three most popular social media worldwide – Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. We did not monitor local social media pages as we believe that for better promotion more international services should be used.

First, several festivals are promoted using the organization’s page and are events developed under one brand. This makes a festival less visible compared to others but attracts tourists to one destination for several events. Second, the Haro Wine Festival has several ‘official’ Facebook pages, while no other social media are used. This festival is from the 50+ age group and, despite attracting both categories of tourists, it is held at the same place for a long period of time and many local websites provide information about this festival. Third, there is a festival that stopped using social media almost during the event on Twitter and Instagram but it is still active on Facebook – the Budapest Wine Festival. That proves our theory that Facebook is the most popular social media in the world.

Almost all festivals have Facebook pages; Twitter is used by almost 60% of the festivals, and Instagram – by 72%. The most notable festivals are a young festival called Tasting Australia with more followers on Instagram than on Facebook (29,000 vs 26,000), the New Orleans Wine and Food Experience from the middle group, which has the highest numbers on Facebook and Instagram in the group and an old festival called Vinitaly with the highest numbers for all social media in the group, that could be linked to festivals in other countries (China, Russia, the USA, Germany, Canada, the UK). The numbers of followers on social media for all age groups are also presented (Table 3).

Table 3 — Numbers of followers on social media

|

Social Media |

Young festivals |

Middle festivals |

Old festivals |

|

|

400–25,000 |

1,200–40,000 |

1,000–165,000 |

|

|

3,700–5,300 |

400–12,500 |

1,800–23,500 |

|

|

2,000–29,000 |

600–12,700 |

100–13,000 |

Overall, the activity on social media does not depend on the age group of the festival, even though it is one of the important factors in event promotion.

Social Media analysis

To study the differences in wine festival marketing strategies, several festivals were chosen to compare their digital marketing appearance on social media. Since the analyzed material comes from secondary sources, to evaluate the extent of presence we had to choose festivals with full media coverage, that could be gained by the data available on all three social media and the recent activity. An additional requirement was the extent of the festivals’ presence in COVID-19 situation.

We discovered that less than 50% of all festivals use three social media (Table 4). Only the festivals that have event pages were taken into account. The number of followers is as of 1 March.

‘Recent activity’ refers to the recent activity on all social media in April 2020 that has decreased the number of festivals by half

(Table 5).

The criterion of the festival presence on social media in the COVID-19 situation does not decrease the number of the wine festivals.

The Popsters website was chosen for the social media analysis, as it provides a variety of tools for the analytics of posts, hashtags, and user engagement over a specific period of time; and data on each festival for three social media were analyzed using these criteria. The data was collected for the period from the page creation till the end of April 2020. The activity was analyzed for all this period, however specific emphasis was made on the last three years and dates of the festivals.

The International Pinot Noir Celebration page on Instagram could not be analyzed because of the age limit disclaimer (21+). Interestingly, none of other wine festivals’ pages has this disclaimer, even though there are limits for drinking alcohol in every country. The other five Instagram pages of wine festivals were analyzed on Popsters, as the platform provides considerable benefits in analysis.

Table 4 — Festivals with social media pages in Facebook*3, Twitter and Instagram* (followers) № Festival’s name Country Facebook* Twitter Instagram*

|

Young festivals |

|||||

|

1 |

Nantucket Wine & Food Festival |

USA |

5,315 |

3,735 |

3,219 |

|

2 |

Bordeaux Fête le Vin |

France |

20,589 |

5,296 |

2,917 |

|

3 |

Tasting Australia |

Australia |

25,759 |

4,553 |

28,800 |

|

Middle festivals |

|||||

|

4 |

Vancouver International Wine Festival |

Canada |

6,590 |

12,500 |

1,900 |

|

5 |

New Orleans Wine and Food Experience |

USA |

39,006 |

6,686 |

12,700 |

|

6 |

Boston Wine Festival |

USA |

1,232 |

374 |

662 |

|

7 |

International Pinot Noir Celebration |

USA |

8,827 |

3,496 |

2,777 |

|

8 |

Le Marathon des Chateaux du Medoc |

France |

32,019 |

1,569 |

5,628 |

|

9 |

Marlborough Wine & Food Festival |

New Zealand |

9,015 |

1,055 |

3,070 |

|

Old festivals |

|||||

|

10 |

Niagara Grape & Wine |

Canada |

20,078 |

9,036 |

9,236 |

|

11 |

Grape Harvest Festival |

France |

14,408 |

1,837 |

2,341 |

|

12 |

Vinitaly |

Italy |

164,818 |

23,500 |

12,900 |

Table 5 — Recently active festivals on social media

|

№ |

Festival’s name |

Country |

|

|

|

|

Young festivals |

|||||

|

1 |

Bordeaux Fête le Vin |

France |

20,589 |

5,296 |

2,917 |

|

2 |

Tasting Australia |

Australia |

25,759 |

4,553 |

28,800 |

|

Middle festivals |

|||||

|

3 |

Vancouver International Wine Festival |

Canada |

6,590 |

12,500 |

1,900 |

|

4 |

International Pinot Noir Celebration |

USA |

8,827 |

3,496 |

2,777 |

Old festivals

|

5 |

Grape Harvest Festival |

France |

14,408 |

1,837 |

2,341 |

|

6 |

Vinitaly |

Italy |

164,818 |

23,500 |

12,900 |

There is no connection between the social media activity and the festivals’ age. On Facebook*, the peak of activity tends to be on the dates of the festival, but there are also festivals that are active before the event and throughout the year, while on Twitter, the tendency is downward. Earlier before 2016, wine festivals used to be more active on Twitter, but now all festivals make numerous posts mostly on the dates of the festival. The only festival that tries to keep up with this pace of activity throughout the year is the Grape Harvest Festival. The International Pinot Noir Celebration is only active during the event. The tendency of Instagram* posts may look confusing as only one festival maintains its activity during the year (Tasting Australia). The Vancouver International Wine Festival is active two weeks before the festival and on the dates of the event. In the case of Vinitaly, it was found out that the activity is much higher outside the dates of the festival that makes it possible to assume that they use Instagram to promote other events.

The Engagement Rate (ER) of page visitors highlights interesting content at specified time. Usually, this rate was distributed at festival dates for the social media in question. On Facebook * , the exception is Tasting Australia that is more engaging on other times, which means that the content is more interesting for other events. On Twitter , Vinitaly has a higher ER during the dates of event with peaks on other dates, which proves that the other events are popular. The Grape Harvest Festival is active on Twitter throughout the year,

3 * Facebook and Instagram are recognized as an extremist organization in the Russian Federation

with only two considerable peaks during the page activity time, which implies a necessity of reviewing and changing the content-making strategy. For Instagram * , the ER goes along with post activity only for Vancouver International Wine Festival and Bordeaux Fête le Vin. Vinitaly that appears to be more active outside the event dates, attracts more engagement especially on the wine festival dates. Tasting Australia has a good ER during the whole period, the overall engagement is high level which proves the understanding the target audience.

The hashtag analysis was done to define main trends, as the age group does not reflect a strategy of hashtag use. Based on the most popular hashtags, the overall trend is seen for all festivals. The hashtags used contain the information on full and short names of the festival (#vinitaly, #tastingaus), which highlights that hashtags tend to be shorter, the festival’s name and the year (#bfv2018, #fdvm2014), which may help to identify the most active years, the location (#paris18, #paris, #bor-daux), wine products or grapes (#italianwine, #pinotnoir). The hashtags differ from the Social Media, only Vancouver International Wine Festival have the same most popular hashtag on three Social Media (#viwf).

However, the analysis of relatively active hashtags shows that hashtags used by visitors are the name and year of the festival, countries and places with or without the year (#au, #france, #france2020), and wine-related words (#wine, #winelover). This proves that some of the hashtags used by wine the organizers are not used by the visitors.

Overall, the social media analysis gives us grounds to conclude that the wine festivals that we studied do not actively use all social media and that there is no connection between the festival age group and social media activity. Wine festivals tend to choose one of the promotion strategies on social media, that is to be active:

-

• only during the event;

-

• before and after the event, and on the dates of the festival;

-

• throughout the year.

Just a few festivals choose the third strategy (Tasting Australia, Vinitaly) and none of the festivals confirm it on all social networks. The hashtags differ across the social media and visitors do not use some of the hashtags suggested by the organizers.

Overall, all studied criteria were analyzed based on the impact they have on the festival promotion (Table 6).

|

Table 6 — Criteria affecting the festival development |

|

|

Criteria |

Impact |

|

Years of organization |

Neutral |

|

Number of visitors |

Neutral |

|

International visitors |

Positive |

|

Availability of dates for future period |

Positive |

|

Collaboration with events |

Positive |

|

Collaboration with other businesses |

Positive |

|

One brand positioning |

Positive |

|

Resources involvement into organization |

Positive |

|

Surrounding infrastructure development |

Positive |

|

Availability of Facebook page |

Positive |

|

Social Media activeness not only during the festival |

Positive |

|

Local scale of event |

Negative |

|

“Selling” attitude |

Negative |

Afterwards, for the classification of the studied festivals we took every positive factor as plus one point and every negative as minus one point, graded all 29 festival and defined classification types (Table 7).

Wine festival and wineries cross-marketing

15 out of 29 festivals (52%) do not mention the names of participating wineries, which is below the expected result. Statistical analysis revealed no significant connection between the age of a festival and its tendency to publish participant lists (p-value = 0,962; Cramer’s V= 0,051). Additionally, the number of social media followers does not demonstrate any statistically significant relation to the tendency to disclose the names of participants (p-value = 0,364; Cramer’s V = 1). Festival grading also does not confirm any connection with tendency to publish a lists of participants (p-value = 0,900; Cramer’s V = 0,313).

Table 7 — Festivals grading with classification degree

|

Classifica- Festival Grade |

|

|

tion type |

|

|

Tasting Australia |

7 High |

|

Niagara Grape & Wine |

7 High |

|

Haro Wine Festival |

7 High |

|

Rheingau Wine Festival |

7 High |

|

Bordeaux Fête le Vin |

6 High |

|

The Old Vine Festival |

6 High |

|

Vinitaly |

6 High |

|

FestiVini Saumur-Champigny |

6 High |

|

Vancouver International Wine Festival |

6 Medium |

|

Habits de Lumière Epernay |

5 Medium |

|

Festa dell’Uva |

5 Medium |

|

New Orleans Wine & Food Experience |

5 Medium |

|

Le Marathon des Chateaux du Medoc |

5 Medium |

|

Nantucket Wine & Food Festival |

4 Medium |

|

Yerevan Wine Days |

4 Medium |

|

Jerusalem Wine Festival |

4 Medium |

|

Conegliano Valdobbiadene Festival |

4 Medium |

|

Chianti Classico Expo |

4 Medium |

|

Boston Wine Festival |

4 Medium |

|

Marlborough Wine & Food Festival |

4 Medium |

|

Budapest Wine Festival |

4 Medium |

|

Grape Harvest Festival |

3 Low |

|

Sonoma County Harvest Fair |

3 Low |

|

Millésime Bio |

3 Low |

|

Vienna Wine Fest |

2 Low |

|

Ardesio DiVino |

2 Low |

|

International Pinot Noir Celebration |

2 Low |

|

National Wine day in Moldova |

1 Low |

|

Limassol Wine Festival |

0 Low |

Consequently, none of the primary hypotheses was confirmed. Additionally, it was noted that festivals that do not disclose participant lists can be categorized into two types: the first group randomly uses pictures of wine bottles and mention brands of participating producers (not as a part of announcement) on their social media and websites, and the second category does not even post any pictures of labelled bottles on their Instagram missing any indicator of origin and belonging to any winery’s brand).

However, another important finding was made during the analysis of the data. There is a significant statistical connection between the origin of a festival (festivals of the Old World or the New World) and the tendency to disclose the festival’s participants (Fisher’s Extract Test = 0,003; Cramer’s V = 0,545), which means that the New World and the Old World countries approach announcing the festival’s participants list differently. In this case, Fisher’s Extract Test was used for the reason that the crosstab based on the considered parameters had some values below 5. The New World’s festivals tend to disclose their participating wineries list more often (88%) compared to the Old World countries (32%). It is conventionally undermined that the Old World include continents known before the Age of Discovery, and the New World regions are those that become known after. However, in this paper we appeal to the classification used in the wine industry, in which the Old World include countries with a long history of winemaking traditions, and the New World also includes both conventional New World countries and new markets located outside of Europe and the Middle East, e.g. South Africa and China (Li, Hua, et al. 2018).

Discussion

Main contributions

This research contributes to the field of wine festivals promotion. Due to the lack of literature on the subject, this paper helps find a new approach to classify wine festivals according to their promotional activities. A useful list of criteria used in wine festival promotion was developed. Moreover, we discovered that the years of wine festivals do not play any role in terms of wine festival promotion. As well as other studies suggest (Coghlan et al. , 2017; Mariani and Giorgio, 2017), the current research highlights the importance of connection between place and event, as it plays a critical role in event promotion.

Wine festival strategy

In order to promote a wine festival and to use benefits from the event promotion and territory branding, wine festival organizers should do as many activities as possible from this list:

-

• Attract international visitors to the festival;

-

• Choose the dates for the upcoming event as early as possible and promote it;

-

• Start the Facebook page and use it to

promote the festival;

-

• Maintain the social media activity not only during the festival but throughout the year or at least a few months before and after the event;

-

• Analyze the target audience and choose social network that is more suitable and stay active;

-

• Collaborate with other local and international events;

-

• Collaborate with other businesses and include them into the process of organizing the event;

-

• Use cross-marketing and provide visitors with the information about participating wineries;

-

• Work in collaboration with other local actors to develop regional wine tourism together since it exists within an ecosystem where all elements are interconnected;

-

• Mind local heritage and provide visitors with authentic local experiences;

-

• Diversify wine festival’s activities and scenes to attract different types of visitors;

-

• Build one brand positioning for a festival with other events;

-

• Involve as many resources as possible into the organization of a festival;

-

• Invest into the festival ground infrastructure.

Understanding the wine festival promotion effectively exploiting the place branding concept, practical recommendations to organizing wine festivals in the COVID-19 situation could be suggested.

Recommendations for organizing wine festivals in during COVID-19 pandemic Several business models were analyzed to develop recommendations: the business reference model; the objectives, goals, strategies, and measures model; the component business model, the industrialization of services business model; and the Canvas business model. However, the recommendations were developed based on the Alignment Squared model developed by Ritter (2014), tested by Ritter and Carsten (2019) and later transformed into a practical workbook (Ritter and Carsten, 2020) especially for the current

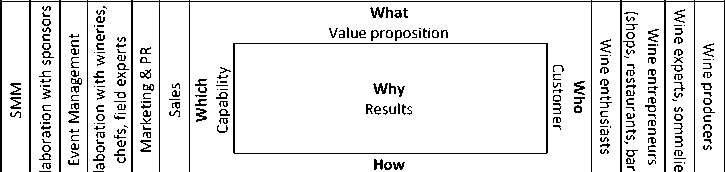

COVID-19 situation as it provides a transformation of previous benefits to include them into a new reality with the extent of their applicability in at times of crisis. All studied marketing activities performed before the COVID-19 pandemic are presented in Fig. 1. The results of these activities for the most successful wine festivals are:

-

• Wine festival audience ranging from 4,500 to 500,000 visitors;

-

• Collaboration with other businesses and events bringing new consumers;

-

• Attracting both international and local visitors;

-

• Inclusion of the wine festival into the regional territory marketing strategy;

-

• Social media activity throughout the year.

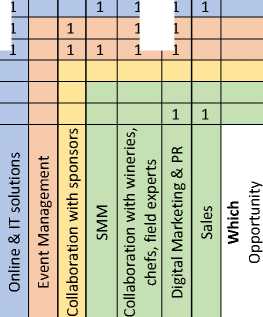

However, the wine festival is obviously extremely influenced by COVID-19 and practical recommendations based on the Alignment Squared model are provided to overcome these changes by implementing (Figure 3). New customer segments could appear, as some of the previous ones will be still interested in the services (wine enthusiasts, wine shops, etc.), some may be closed or go bankrupt such as small wine producers, some may disappear for an uncertain amount of time (restaurants and bars) and some may be found in the new reality seeking for new collaboration (e.g. delivery services). The main value proposition of wine will not change, as people at any time will need in it. Even more so than before, the need to be included into a special community will occur in all customer segments.

1 1 1 1 Being promoted 1 1

1 1 1 Networking 1 1 1

1 1 Becoming a part of the community 1 1 1 1

1 Celebrating 1

1 1 1 Exploring new cultures 1

1 1 1 Wine tasting 1 1 1 1

Value demonstration

1 1 1 1 1 Wine festival 1 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1 Other wine events (masterclass, degustation) 1 1 1

1 1 Face-to-face meetings 1 1 1

1 1 1 Discussion clubs at shops and wineries 1

1 1 Social Media Advertisement 1 1

1 1 Advertisement in restaurants, bars 1 1

Figure 1 – Business model of wine festival organizations before COVID-19 situation

While some propositions will not be possible to organize for some time (celebrating, meeting local culture), new value propositions should be developed to attract customers (promotion to be purchased online). Value demonstration will definitely look different as all possible services provided in person will go online and new methods will emerge: websites and applications for community maintenance, online festivals, online courses, online wine tasting, and video conferences. There will be changes in competences: whereas SMM, marketing, PR, and sales skills will still be important, expertise in event management will not be in demand for an indefinite period of time, and the new environment will raise a need for competences in online and IT solutions.

The possible outcomes of the new strategy are suggested for different periods:

-

• During the crisis – saving the audience with minimal losses;

-

• Right after the crisis – extension of the audience through involving new segments and collaboration with new businesses;

-

• New normal – organization of online collaboration and uniting the wine community.

The model also includes the activities that should be performed by wine festival organizations (Table 8).

It should be mentioned that companies that developed new ways of working during the COVID-19 pandemic will become even more successful by extending their target audience through online marketing. The territory branding will still be relevant for some time after the crisis and the newly attracted audience will increase the popularity of wine festivals and again all the activities that were ceased and lost opportunities will be highly important.

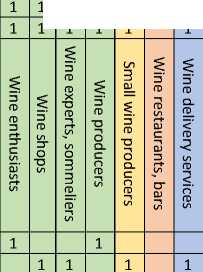

Promotion for online orders

Celebrating

Exploring local culture Networking

Becoming a part of the community

Wine tasting

What

Value proposition

Why

Results

How

Value demonstration

1 1 1 1

g

-

1 1 Social Media Advertisement

-

1 1 1 Personal e-mails & invitations

Advertisement in restaurants

Wine festival

Other wine events (masterclass, wine tasting) Face-to-face meetings

Discussion clubs at the shops and wineries

1 1 1 1 1 1 Website or app to maintain the community

1 1 1 1 1 1 Online wine festival

1 1 1 1 Online courses, degustation (with delivery)

1 1 1 Online discussion clubs

1 1 1 Video meetings

Figure 2 – Business model of wine festival organizations after COVID-19 situation

Limitations

This study is subject to certain limitations. First, the sample is selected randomly from a wine festivals’ list obtained via Internet. Second, the scope of the study is limited to different wine festivals all over the world. Third, only the content analysis method was used in order to identify the criteria that have an impact on festival promotion. Fourth, only digital data was used to conclude on if a festival opened a participant list for cross- marketing purposes.

Future research

The findings of this research paper could contribute to the literature on wine festivals and event promotion and especially ways to be relevant and effective in the time of pandemic. The topic of wine festival promotion has not been studied yet, despite its practical implications. This concept can help in terms of organizing festivals worldwide, as well, that could be beneficial in order to compare similarities and differences in different countries. Festival organization management can deploy the results of this study to find new promotion methods and to implement the suggested recommendations to overcome the consequences of COVID-19.

Moreover, the research society can find a new direction to design an entire strategy of wine festival promotion and studying separate concepts of the criteria. Also, the development of a full base of wine festivals worldwide could be beneficial for future research.

Table 8 — Activities that should be performed within a new business model

|

с” 'о ф с о |

|

Additionally,

to maintain the community

|

Additionally,

|

|

ф с о о |

|

|

– |

|

м с 'о о к |

|

|

|

|

Ы) 'о га |

|

Hold small elite wine events & parties |

Develop a unified standard for all events through a combination of offline and online |

Conclusion

The research study helps fill the gap in the literature about wine festival promotion and place marketing providing a full list of criteria that could be used in order to analyze wine festivals and classify them. The suggested wine festival promotion strategy is beneficial for wine festivals that are willing to gain competitive advantage. Recommendations developed for wine festival organizations could be used to overcome the consequences of COVID-19 and to transform the best practices from already gained high positions in place branding into new ways of working.

Список литературы Developing strategy of wine festival promotion

- Aylward, D. K. (2003). A documentary of innovation support among New World wine industries. Journal of Wine Research, 14(1), 31-43.

- Bjork, P., & Kauppinen-Raisanen, H. (2014). Culinary-gastronomic tourism - a search for local food experiences. Nutrition & Food Science, 44(4), 294-309.

- Bose, S., Roy, S. K., & Tiwari, A. K. (2016). Measuring customer-based place brand equity (CBPBE): An investment attractiveness perspective. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(7), 617-634.

- Brown, G., & Getz, D. (2006). Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: a demand analysis. Tourism management, 27, 146-158.

- Brownett, T., & Evans, O. (2019). Finding common ground: The conception of community arts festivals as spaces for placemaking. Health & Place, In Press. doi: 10.1016/j.health-place.2019.102254.

- Campbell, G., & Guibert, N. (2006). Introduction: Old World strategies against New World competition in a globalizing wine industry. British Food Journal, 108(4), 233-242.

- Carra, G., Mariani, M., Radic, I., & Peri, I. (2016). Participatory strategy analysis: The case of wine tourism business. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedía, 8, 706-712.

- £ela, A., Knowles-Lankford, J., & Lankford, S. (2007). Local food festivals in Northeast Iowa communities: a visitor and economic impact study. Managing Leisure, 12(2/3), 171-186.

- Chang, W., & Yuan, J. J. (2011). A taste of tourism: visitors' motivations to attend a food festival. Event Management, 15(1), 13-23.

- Cieslikowski, K. (2016). Event marketing, Podstawy teoretyczne i rozwiqzania praktyczne. Katowice: Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego im Jerzego Kuluczki w Katowicach.

- Cleave, E., Arku, G., Sadler, R., & Gilliland, J. (2016). The role of place branding in local and regional economic development: Bridging the gap between policy and practicality. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 207-228.

- Coghlan, A., Sparks, B., & Liu, W. (2017). Reconnecting with place through events. Collaborating with precinct managers in the placemaking agenda. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 8(1), 66-83.

- Davis, A. (2017). Experiential places or places of experience? Place identity and place attachment as mechanisms for creating festival environment. Tourism Management, 55, 49-61.

- Dodd, T., Yuan, J., Adams, C., & Kolyesnikova, N. (2006). Motivations of young people for visiting wine festivals. Event Management, 10(1), 23-33.

- Galloway, G., Mitchell, R., Getz, D., Crouch, G., & Ong, B. (2008). Sensation seeking and the prediction of attitudes and behaviours of wine tourists. Tourism management, 29(5), 950-966.

- Getz, D. (2008), "Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research", Tourism Management, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 403-428.

- Getz, D. (2010). Event tourism: Pathways to competitive advantage. Presentation at Lincoln University, Christchurch, New Zealand. URL: www.lincoln.ac.nz (Accessed on February 2, 2020).

- Getz, D., & Page, S. (2016). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Management, 52, 593-631.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2018). Event tourism and event imposition: A critical case study from Kangaroo Island, South Australia. Tourism Management, 64, 73-86.

- Hjalager, A.-M., & Kwiatkowski, G. (2018). Entrepreneurial implications, prospects and dilemmas in rural festivals. Journal of Rural Studies, 63, 217-228.

- International Organization of Vine and Wine. URL: https://www.oiv.int (Accessed on February 3, 2022).

- Kim, Y. H., Goh, B. K., & Yuan, J. (2010). Development of a multi-dimensional scale for measuring food tourist motivations. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, 11(1), 56-71.

- Kim, Y. H., Taylor, J., & Ruetzler, T. (2008). A small festival and its economic impact on a community: a case study. Frontiers in Southeast CHRIE Hospitality and Tourism Research, 12(2), 49-52.

- Lee, I., & Arcodia, C. (2011). The role of regional food festivals for destination branding. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13(4), 355-367.

- Lee, W., Sung, H., Suh, E., & Zhao, J. (2017). The effects of festival attendees' experiential values and satisfaction on re-visit intention to the destination: The case of a food and wine festival. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(3), 1005-1027.

- Li, Hua, et al. (2018). The worlds of wine: Old, new and ancient. Wine Economics and Policy, 7.2, 178-182.

- Mabillard, V., & Vuignier, R. (2017). The less transparent, the more attractive? A critical perspective on transparency and place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 1-12. doi: 10.1057/s41254-016-005.

- Mainolfi, G., & Marino, V. (2018). Destination beliefs, event satisfaction and post-visit product receptivity in event marketing. Results from a tourism experience. Journal of Business Research. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.001.

- Mariani, M. M., & Giorgio, L. (2017). ''Pink Night" festival revisited: Meta-events and the role of destination partnerships in staging event tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 62, 89-109.

- Marzo-Navarro, M., & Pedraja-Iglesias, M. (2010). Are there different profiles of wine tourists? An initial approach. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 22(4), 349-361.

- Parker, C., Roper, S., & Medway, D. (2015). Back to basics in the marketing of place: The impact of litter upon place attitudes. Journal of Marketing Management (ahead-of-print), 1-23.

- Ramkissoon, H., Smith, L., & Weiler, B. (2013). Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: a structural equation modelling approach. Tourism Management, 36, 552-566.

- Richards, G. (2017). From place branding to placemaking: the role of events. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 8(1), 8-23. doi: 10.1108/IJEFM-09-2016-0063.

- Ritter, T., & Carsten, L. P. (2020). The impact of the corona crisis on your business model: Workbook., Frederiksberg: Copenhagen Business School.

- Smith, S., & Costello, C. (2009). Segmenting visitors to a culinary event: motivations, travel behavior, and expenditures. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 18(1), 44-67.

- Sohn, E., & Yuan, J. (2013). Who are the culinary tourists? An observation at a food and wine festival. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(2), 118-131.

- Thanh, T. V., & Kirova, V. (2018). Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. Journal of Business Research, 83, 30-37.

- Todd, L., Leask, A., & Ensor, J. (2017). Understanding primary stakeholders' multiple roles in hallmark event tourism management. Tourism Management, 59, 494-509.

- Van Niekerk, M. (2014). Advocating community participation and integrated tourism development planning in local destinations: the case of South Africa. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 3(2), 82-84.

- Velikova, N., Slevitch, L., & Mathe-Soulek, K. (2017). Application of Kano model to identification of wine festival satisfaction drivers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(10), 2708-2726. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-03-2016-0177.

- Viljoen, A., Kruger, M., & Saayman, M. (2017). The 3-S typology of South African culinary festival visitors. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(6), 1560-1579.

- Vuignier, R. (2017). Place branding & place marketing 1976-2016: A multidisciplinary literature review. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 14, 447-473. doi: 10.1007/s12208-017-0181-3.

- Woosnam, K. M., McElroy, K. E., & Van Winkle, C. M. (2009). The role of personal values in determining tourist motivations: an application to the Winnipeg fringe theatre festival, a cultural special event. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 18, 500-511.

- Yolal, M., Gursoy, D., Uysal, M., Kim, H. L., & Karacaoglu, S. (2016). Impacts of festivals and events on residents' well-being. Annual Tourism Research, 61, 1-18.

- Yuan, J. J., Cai, L. A., Morrison, A. M., & Linton, S. (2005). An analysis of wine festival attendees' motivations: a synergy of wine, travel and special events? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(1), 41-58.

- Zenker, S., & Braun, E. (2010). Branding a city: a conceptual approach for place branding and place brand management. Paper presented at 39th European Marketing Academy Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1 June 2010 - 4 June 2010.

- Zhang, C. X., Fong, L. H. N., & Li, S. (2019). Co-creation experience and place attachment: Festival evaluation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 193-204.

- Ziakis, V. (2013). Event Portfolio Planning and Management: A Holistic Approach. London: Routledge.