Economic role of tourist cooperation in Hungary

Автор: Ritter Krisztin, Virg Gnes

Журнал: Региональная экономика. Юг России @re-volsu

Рубрика: Фундаментальные исследования пространственной экономики

Статья в выпуске: 3 (17), 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Modern tourism was developed owing to the economic, social and technological changes in the XX century. The establishment of sustainable and competitive tourism is a trend that can be observed worldwide. Therefore, in countries interested in tourism, such as Hungary, it has become an important development direction to establish an institutional structure based on tourism destination management (TDM). Over the past decade developing organizations did not affect only our country’s most advanced touristic areas (eg.: Heviz, Lake Balaton, Siofok, Hajdúszoboszló, Buk), but also an increasing number of destination organizations were set up in rural areas dealing with a variety of economic and social problems. Along this the question could be raised about what the role of these associations were / is, and how efficiently could / do they operate.The questions are whether this institutionalized cooperation can work effectively in our country; what effects do they have in the life of a region; and if these effects can be measured, which indicators are the most suitable ones to do so?

Hungary, tourism, cooperation, association, destination, sustainability, indicators, analysis, economical effect

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149131198

IDR: 149131198 | УДК: 338.48 | DOI: 10.15688/re.volsu.2017.3.5

Текст научной статьи Economic role of tourist cooperation in Hungary

DOI:

The main goal was to create local and regional organizations and to change existing regional – and state level tourism organizations. The development of the management-oriented associations began ten years ago and many local and regional organizations have been created since then. The first TDM organization was founded in 2011 in the Balaton-region and the Hungarian TDM Association was founded in the same year to ensure state advocacy. After many steps the Hungarian TDM system seemed to be ready. In 2008 direct tenders were announced for the first time to help the organizational development. The National Tourism Development Conception (NTK) considered the strengthening of the indigenous institutional structure as a priority development plan.

Many concerns emerged regarding the long term sustainability, legal controllability and real acts of these organizations. In the past few years numerous researches were conducted to examine their competitiveness [17; 19] and sustainability [10].

A decade passed since the beginning and the organizations have fulfilled TDM tenders, have plenty of experience but these were never examined before in previous researches. Nor did they pay attention to what role do these associations play in the rural economy, how do they cooperate or what effects do they have on the life of a rural region and – if possible – could these effects be measured.

The actors of the tourism sector had to face numerous challenges like the effects of globalization, the fast changing touristical market or the intensive competition [5]. The development of a modern tourism controlling and operating system is in need which would assure opportunity to every participant of the industry to cope with these challenges. Cooperations had been always playing an important role in the life of mankind but networks are becoming more and more momentous in every aspect of life since the past few decades. In tourism it is even more important to create networks since there are uncountable independent and often small units of business [16]. The specialty of the tourism industry is that it is mainly made up of micro- and small enterprises, it consists many communities (companies, enterprises, non-profit organizations, local inhabitants) while in most of the cases the public sector ensures the developments (like infrastructural background). Succesful cooperation could only become implemented if the right partners are brought together in a network and whose acts are coordinated by a proper and competent person or staff, clear agreements are made and they pay attention to managing connections with other networks. To Panyor and his co-authors [14] notions I would like to add the importance of financial stability, clear program, effective planning structure and flexible departments like how Soisalon-Soininen and Lindroth [16] explain when discussing the effectiveness of networks. It is clearly visible that numerous conditions must be considered while developing and operating a network. The networks shall be classified to three types: horizontal, vertical and diagonal networks – according to literature. Horizontal cooperations can be developed between personas working in the same geographical area (like product improvement groups). Diagonal cooperations are usually created between different industries and service providers working on different levels. In case of vertical networks organizations of different territories and operational levels are connected – TDM organizations are classified in this category [14].

“Destination” comes from a latin meaning foreordained, in a touristical meaning it appears as reception area [9; 13] so it is the basis of tourism [3]. Many definitions are accepted in international literature. According to the World Tourism Organizations (UNWTO) definition from 1993, “destination” is a physical space which shall be choosen by the visitor considering the attractions, services and institutions but from the suppliers point of view it is a territorial unit being for sale [15]. In international literature “destination” is also represented as a provider area of groups of products or services which is able to attract visitors and provide experience [2]. Other definitions are focusing on the experience provided, like Kaspar [8] who states that “destination” is the location of staying and gaining experience during traveling. Crouch and Ritchie [3] focus on the experience too which is gained by a tourist while traveling so the experience is the basic touristic product.

Definitions of this concept can be found also in hungarian literature. Lengyel [9] states that “destination” is reception area which can provide touristical products to visitors in a complex way. Tőzsér [19] tried to sum up the definitions appearing in literature and in his statement “destination” is a region or area where different attractions, products and services can attract tourists for at least a day and it can provide a complex experience for them. I personally agree with this statement, I do think that “destination” is a reception area where attractions, products and services attract visitors. It can be stated that the “destination” is the basic unit of tourism which is local and consists of numerous participants who cooperate in a complex way [2]. Inhabitants, service providers and other attendees of the market play an important role [1]. According to Sziva 17] it is a fact that the “destination” is a territorial, social and economical unit therefore its sustainability must be kept as a priority. It is very important that the participants should think as partners about each other, not competitors [2; 9].

It is also true that a specific destination is a touristic product with an image which competes with other destinations on the market of tourism [18]. Tourists have an image in their mind about their travel stop and they can differentiate between destinations therefore positioning is highly important. Such messages and advertisement shall be transferred to them which make that specific stop unique. The most convenient way is to create its own brand [19]. Thus marketing should be far-reaching and extensive.

In conclusion “destination” is a territorial (geographical, economical, social) unit with an image, it consists of the touristic products and services which are able to attract tourists and generate experience. The operation of the market is guaranteed by the participants working in cooperations and the whole process is coordinated by the Tourism Destination Management.

Piskóti and his co-authors defined destination management the following way: “The attractions organization into networks, convertion to a modular product, creating the product attached to the destination to be marketable and competitive and then selling it with the ambition of preserving sustainable development, increasing the development of a specific geographical area and the wellness of local inhabitants while reaching success on the tourism market” [15, p. 7].

Piskóti and his co-authors [15] and Dávid and his co-authors [4] agreed that the main problem is that there is no such planning and organizationcoordinating structure which would have proper competence and financial stability in our homelands tourism. The main point of tourism destination management was already defined in the past several times. For example the World Tourism Organization stated in 1979 that the most important role of these management organizations is to help and coordinate the acts of non-profit and private participants of a specific tourism region. Buhalis [2] declares that management organizations are responsible for tourism products and their development, creating a partnership network in their region and making the destination capable of supplying positive experience to visitors.

The most complex definition of tourism destination management originates from Víg who said the following statement about the essence of the new outlook: “The long term organized cooperation between voluntary partners who treat the destinations products and other services as a unit in a complex way to optimalize the tourist’s experience and the effects of tourism while considering the points of sustainability” [20, p. 119]. The goal is to create and operate sustainable and competitive tourism [7]. The purpose of the TDM organization is to ensure a complex experience and satisfy the needs of visitors while creating social, economical and environmental advantages to local inhabitants, involving them in developments and decision processes [9; 19].

-

II. Materials and Method

Discovering the general status of the Hungarian TDM system, getting to know the background of the organizations operations, measuring the activity of participants and the effectiveness of cooperations were amongst the goals of this research. We found it important to study how the organizations see the sustainability of the TDM structure and their own company and what main tasks do they find the most urgent in the current situation. Furthermore our main goal was to diagnosticate whether the TDM organizations are affected by effects of rural economy and if they are then how could it be measured.

We established a nation-wide TDM questionnaire in 2015 on the basis of professional literature and our own experiences. The TDM organizations which already have a registration number at Ministry of National Economy were subject of our research 1. According to professional responses to pilot surveys we have performed the necessary corrections and then the questionnaire was sent to all (85) TDM company which have a registration number.

The questionnaire contained 25 questions about the general information of the organizations, the number variety of members they have, their budgets, members willingness to cooperate, tender activities, sustainability, contributing factors of developing the organizations system, the economical roles of the organizations and the measurability of these roles.

-

III. Results

Despite the repeated requests the number of responses stayed very low, 18.8 %. Only 16 out of the 85 registered TDM organizations answered the questions. However the actuality of this discussion is clearly visible as there are numerous Bsc/Msc and PhD research in this topic, “the high interest” and loads of questions might be the reason too why most of the organizations did not respond. Although we could not represent the whole crowd we think that the results are correct according to our previous researches and interviews with professionals of the field of the TDM system.

The first two questions were about the year when the organization was founded (Fig. 1). If we take year 2009 as basis (because the first tender was issued in this year) then the proportion of organizations founded before 2009 is 38 %, founded in 2009 is 56 % and only 6 % of the responding organizations started operating after 2009. This allows us to think that the foundation of TDM organizations was closely related to tender activities.

Most of the completors of the questionnaire (87,5 %) were local organizations and micro-regional organizations came with a proportion of 12,5 %. 69 % of them were operating as associations and 31 % as nonprofit kft. Considering the number of members they started with and the number of members they had at the time of responding we can state that nearly all of them (87,5 %) doubled this number. The members are very various regarding their activities. Civil associations, accommodation providers, entrepreneurs, councils are dominating at most of the organizations but private accommodations and other participants are also present. In the wine regions wine producers are participants as well with different proportions in each organization.

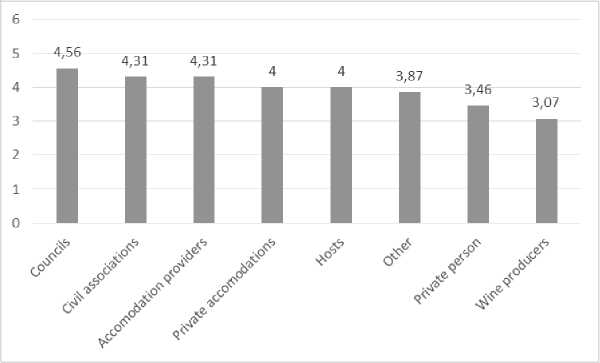

We also investigated how the different participants are willing to cooperate (Fig. 2) and how the organizations see the joint work. On average they say that councils can cooperate well while civil associations, accommodation providers, hosts, private accommodations and other entrepreneurs cooperate fairly well. Cooperation is a bit harder with private persons and it is the hardest with wine producers.

Generally speaking the organizations income consists mostly of counsil membership fees and other supports (40 %) and other non-counsil members membership fees (30 %). On average the incomes through tenders were lower (20 %) which could be possible thanks to the passive tendering period when the questionnaire was issued. Most of the winning tenders from the 2007–2013 budgetary period had been completed already while the new tenders were issued in February 2016. Incomes after their own activities and sponsorship stayed as low as 10 %.

Considering the proportion of expenses the most significant ones are the operational costs.

Nearly one quarter of the expenses is spent on producing marketing matters while online marketing, adverisements and dissemination take a very small

56%

38%

-

■ Before 2009

-

■ 2009

-

■ After 2009

Fig. 1. Foundation of the responding organizations Sourse: own research and editing, 2017.

Fig. 2. Willingness to cooperate of different participants (average)

Note: On a scale from 1 to 6 where 1 = inadequate; 6 = excellent.

Sourse: own research and editing, 2017.

proportion. Only 25 % of the organizations have downpayment tender.

The next few questions were about their experience and work on tenders. Most of the TDM organizations (94 %) took the tender opportunities, only 6 % could not realize tender activities between 2007–2013 due to lack of capital.

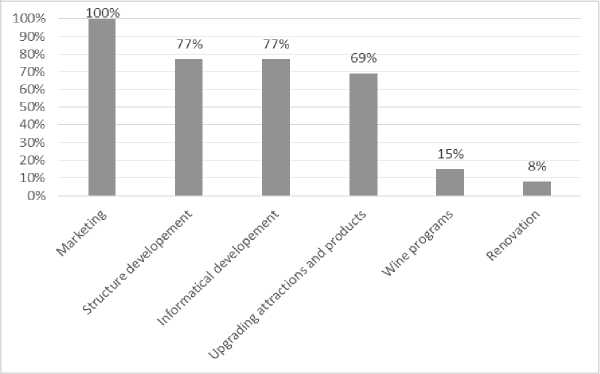

It is obvious that the investigated TDM organizations used tender aids although they had to face many difficulties. Most of them got supported to develop tourism and their own organization. I found that their sustainability is excessively dependent from tenders which is impractical in a long-term strategy. Marketing could be found amongst tender activities in all of the investigated organizations (100 %) but structure developement (77 %), informatical developement (77 %) and upgrading attractions and products (69 %) were highly important as well. 15 percent of the associations organized programs about wine and 8 % of them spent some of the support on renovation (Fig. 3).

The next question was about the long term sustainability of the hungarian TDM in the present situation (Fig. 4). Responders could mark their opinion about professional, legal and financial sustainability on a scale from 1 to 6. From a professional perspective the average was 4,13 so the organizations are partially sustainable from this point of view according to employees in a TDM. Long term sustainability is not so obvious legally and the cause of the lower rating (3,46) could be the lack of tourism law. The instable financial background is the weakest point of long term sustainability with an average of 2,26. Most of the organizations believe that the TDM structure is unsustainable in the current situation. So urgent changes are needed on legal and financial fields to help the institutional system operate succesfully.

The organizations had to evaluate themselves in a separate question (on a scale from 1 to 6) especially financially, not counting the TDM tenders. They find themselves partly sustainable (3.73) on short terms, it becomes more unsure on midterms (2.86) while they find their work unsustainable on long terms (2.13).

We also investigated what their opinion is about the impact of destination organizations on the rural

Fig. 3. Usage of supports, %

Note: Multiple responses could be given.

Source: own research and editing, 2017.

Fig. 4. Average opinions of responding organizations about the long term sustainability of the hungarian TDM system

Note: on a scale from 1 to 6 where 1 = totally unsustainable; 6 = totally sustainable.

Source: own research and editing, 2017.

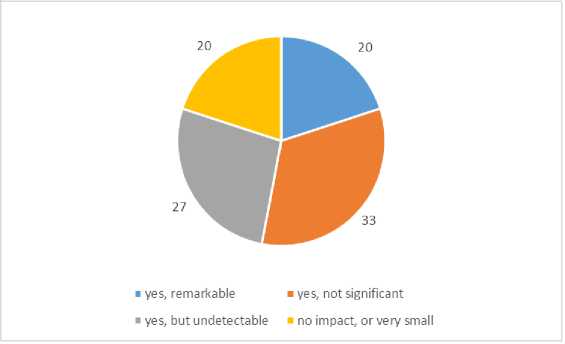

economy in different towns and regions (Fig. 5). 20 % of the completers believe that these companies do not affect or have only a very small impact on towns and regions. However, most of the completers (80 %) think that TDM organizations affect the rural economy but they have different opinions about the level of this impact. 20 % of them believe that this impact is remarkable, 33 % thinks that it is not so significant and 27 % of the completers thinks that it undetectable.

The next question was about how could the success of their work in a town or region be detectable (Fig. 6). While one organization did not answer this question, 80 % of the completers find the number of visitors of their webpage the best index and the satisfactory of tourists got 73 %. The number of nights spent by guests and the income from tourist tax were marked in 47 % then the number of guests and tender activity came with 40 % each. The completers find social (33 %), economical indicators (27 %) and the number of attractions (27 %) moderately important. The fullness of accomodations (20 %) and satisfactory of local inhabitants (20 %) were not so popular while the number of visitors at attractions (7 %), local people’s attitude about tourism (7 %) and other (13 %) factors (whitening of return of tourist tax, product development) were the least important indexes.

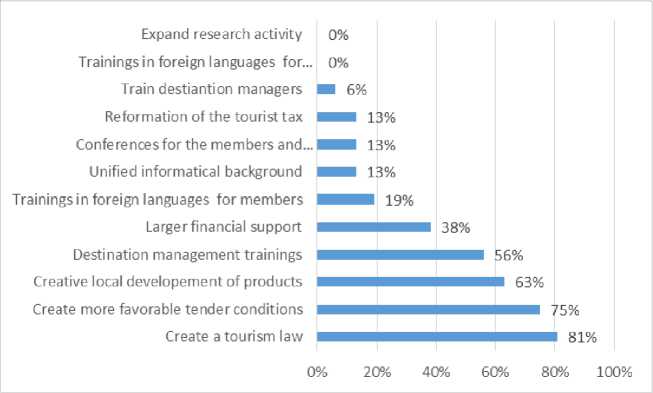

The organizations were asked to share their opinions about what could help promote the national TDM system in the future. They found the creation of a tourism law the most important task (81 %) for future developement. The second most important was to create more favorable tender conditions (regarding the downpayment, easier adminisztration, control), 3 quarters (75 %) of the competers found it important to deal with this. Many competers thought that the creative local developement of products (63 %) and

Fig. 5. The economical impact of a rural TDM organization, %

Source: own research and editing, 2017.

Other ^^" 13,00%

Local's attitude to tourism ^“ 7,00%

Number of visitors at attractions ^" 7,00%

Satisfactory of locals ^^^^^ 20,00%

Fullness of accomodations ^^^^^" 20,00%

Number of attractions ^^^^^^^ 27,00%

Economical indicators ^^^^^^^ 27,00%

Social indicators ^^^^^^^^“ 33,00%

Tenderactivity ^^^^^^^^^^" 40,00%

Number of guests ^^^^^^^^^^" 40,00%

Number of guest nights ^^^^^^^^^^^^^“ 47,00%

Income from tourist tax ^^^^^^^^^^^^^" 47,00%

Satisfactory of tourists ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^“ 73,00%

Webpage visitors ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^“ 80,00%

0,0 0% 20,00% 40,00% 60,00% 80,00% 100,00%

Fig. 6. Indexes measuring the work of a TDM organization

Note: Multiple responses could be given.

Source: own research and editing, 2017.

destination management trainings (56 %) should get bigger attention. 38 % of the competers voted for larger financial support from the council taken away form the tourist tax while 19 % of them thought that trainings on foreign languages would be important for the members of TDM organizations. The unified informatical background, organization of conferences for the managers and members and other tasks like the reformation of the tourist tax war marked at 13 %. Only 6 % found it important to start training destination managers.

In our opinion it is quite surprising that none of the competers marked the training in foreign languages for TDM managers neither did they find the expandation of research activity important (Fig. 7).

In our opinion the TDM organizations could become significant parts of the rural economy if operating correctly, therefore they should play an active role in creating local and regional developemental documents. So we inspected what the organizations think about this and how actively do they participate in creating different level developemental plans currently. 50 % of the TDM organizations could form opinions while 44 % of them were considered as contributors. Only 6 % of them indicated that they have not taken part in the making of such plans.

-

III. Conclusions

The results of the questionnaire proved that most of the hungarian TDM organizations were founded in 2009 and after so the willingness of creation grew significantly following the first tenders. The number

of members were duplicated in every association and cooperational boundaies were expanded which is a positive change. Their willingness for cooperation was inspectedand results show that councils, civil organizations, accomodation and host service providers are the most active. The majority of the organizations applied for tenders and they spent the financial support on marketing, attraction-, product-, organizational and informatical developement. According to the completers the hungarian TDM structure is partly sustainable professionally, legally even less and there are serious problems when it comes to financial sustainability. However when they had to describe the sustainability of their own organization they found cooperations more unstable.

One of the main goals of this research was to inspect whether the TDM associations play any economic role in a region’s life. The majority of the completers thought that these organizations do affect the rural economy but on different levels. We also examined how would it be possible to measure their effectiveness in a town or region. Most of the completers found the number of visitors on their website and the satisfactory of tourists the best index but also the tender activity, the number of guests, the number of nights spent by guests and the income from tourist tax were quite reasonable. The organizations could express their opinion about what would help promote the hungarian TDM system in the future. They found the creation of a tourism law, the creation of more favorable tender conditions, the creative local developement of products and destination management trainings the most important

Fig. 7. Most important tasks in the promotion of the hungarian TDM system

Note: 4 out of 14 had to be marked as important.

Source: own research and editing, 2017.

tasks in future developement. For most of the time the associations were involved in creating developemental plans.

Our first ascertainment is that the research is non-representative as completion rate was 18.8 % despite of multiple requests but according to my practical experiences the results could be typical for the whole system. Connected to this we should highlight that none of the completers considered researching important in the current situation. In our opinion if the associations refuse to fill in questionnaires then it is impossible to draw the course line of improvement which would promote the system. We agree and often experience too that the organizations are engaged in various activities and that they are facing many professional and financial problems every day but reasonable researches should be taken more seriously. We suggest the TDM associations to cooperate with high schools and universities where students could do some useful reserch and surveys during their lessons. This would help students to get to know the practical side of this area and it would also be good for the organizations because they couldget innovative ideas and results.

To maintain the TDM structure for a long term – taking the results in consideration – we would advise the central management and the Hungarian TDM Association to assure more favorable operational and taxation and create more favorable tender conditions (smaller rate of downpayment, more flexible administration, support of creative local developement of products, expansion of etrepreneurial activity). Connected to the developement of human infrastructure inside of an association there should be more state supported destination management trainings, trainings in foreign languages and professional conferences to ensure sustainability in the future.

The results have shown that the roles of TDM organizations could be determined regarding their touristical and other effects. The associations play a side role in rural economy and territorial developement however this is not their main goal. They should apper as unmissable partners to companies dedicateed to the above mentioned goals. This makes it clear that the chances of professional operation shall be ensured (for e.g.: money, competence, etc.) and the creation of a measurement system is in need which would support monitoring activities, and clarifiesthe effects and roles of cooperations in the life of a region. According to our practical experiences we think that a unified index would promote the cohesion inside any organization because the members could see the advantages of participation. We set our goal to create this unified index while keeping in mind that beside the statistical data we should take other factors in consideration as well.

Acknowledgements

EMBER1 EROFORRASOK M1N1SZTER1UMA

“SUPPORTED BY THE ÚNKP–16–3 NEW NATIONAL EXCELLENCE PROGRAM OF THE MINISTRY OF HUMAN CAPACITIES”.

FOOTNOTES

-

1 The list of participants at the Hungarian TDM Association is longer since there are some organizations without registracion number (registration was nut obligatory at the first tenders) although they are operating succesfully as TDM organizations. There are other organizations as well which fulfill the activity of such a tourism organization but they never applied for tenders nor did they apply a registration number.

Список литературы Economic role of tourist cooperation in Hungary

- Aubert A. A térségi turizmuskutatás és tervezés módszerei, eredményei. The methods and results of regional tourism research and design. Pécs, PTE-TTK Földrajzi Intézet, 2007. 391 p.

- Buhalis D. Marketing the competitive destination in the future. Tourism Management, 2000, no. 21 (1), pp. 97-116.

- Crouch G., Ritchie J.B.R. Tourism competitiveness and societal prosperity. Journal of Business Research, 2000, no. 44 (3), pp. 137-152.

- Dávid L., Kovács T., Tóth G., Bujdosó Z., Patkós Cs. A turizmus hatásai és jelentősége a területfejlesztésben. Effects and significance of tourism in regional development. In: Süli-Zakar, I. (szerk.): A terület-és településfejlesztés alapjai II. Budapest -Pécs, Dialógus Campus Kiadó, 2010, pp. 447-468.

- Dávid L., Tőzsér A. Destination Management in Hungarian tourism. In: Applied studies in Agribuiness and Commerce. Budapest, APSTRACT Agroinform Publishing House, 2009, pp. 81-84.

- Káposzta J., Nagy A., Nagy H. Tourism infrastructure index and the distribution of development funds in statistical regions of Hungary. Agrarian Bulletin of the Urals, 2013, no. 12 (118), pp. 80-83.

- Káposzta J., Nagy, A., Nagy H. The impact of tourism development policy on the regions of Hungary. Regional Economy. South of Russia, 2016, no. 11 (1), pp. 10-17.

- Kaspar C. Turisztikai alapismeretek. Basics of Tourism. Budapest, KIT, 1992. 157 p.

- Lengyel M. TDM Működési Kézikönyv. TDM Operational Handbook. Budapest, Heller Farkas Főiskola, 2007. 212 p.

- Lőrincz K., Raffay Á., Hajmásy Gy. A turisztikai desztináció menedzsment rendszer gazdasági fenntarthatósága Magyarországon. The economic sustainability of tourist destination management system in Hungary. 2014. 30 p.

- Nemzeti Turizmusfejlesztési Koncepció 2014-2024. National Tourism Development Concept 2014-2024. Budapest, Nemzetgazdasági Minisztérium, Nemzetgazdasági Tervezési Hivatal, 2014. 81 p.

- Nemzeti Turizmusfejlesztési Stratégia 2005-2013. National Tourism Development Strategy 2005-2013. In: Turizmus Bulletin, IX. évfolyam, különszám, 2005. Budapest, 2005. 56 p.

- Nyirádi Á., Semsei S. (szerk.). Balatoni TDM füzetek. TDM Booklets to Balaton. Siófok, Balatoni Integrációs és Fejlesztési Ügynökség Kht., 2007. 108 p.

- Panyor Á., Győriné Kiss E., Gulyás L. Bevezetés a desztináció menedzsmentbe. Introduction to the destination management. Keszthely, 2011. 162 p.

- Piskóti I., Hidvéginé Molnár J., Pataki S., Schumpler H., Gulyás I. Desztináció-menedzsment lépésről-lépésre. Destination management step by step. Eger -Miskolc, 2007. 43 p.

- Soisalon-Soininen T., Lindroth K. Regional Tourism Co-operation in Progress. In Lazzeretti L. Petrillo C.S. (Ed.). Tourism Local Systems And Networking. Oxford, Elsevier Science & Technology, 2006, pp. 187-196.

- Sziva I. Turisztikai Desztinációk versenyképességének értelmezése és elemzése Interpretation and analysis of the competitiveness of Tourism Destinations. Ph.D. értekezés. PhD dissertation Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem. Gazdálkodástani Doktori Iskola. Budapest, 2010. 197 p.

- Tasnádi J. Turizmus az Európai Unióban és Magyarországon. Tourism in Europe and in Hungary. Budapest, Magyar Kereskedelmi és Ipari Kamara, 2006. 98 p.

- Tőzsér A. A versenyképes turisztikai desztináció: Új turisztikai versenyképességi modell kialakítása. Competitive tourism destination: developing new tourism competitiveness model. Doktori disszertáció. PhD dissertation, Miskolci Egyetem, Gazdaságtudományi Kar, Vállalkozáselmélet és gyakorlat Doktori Iskolája. Miskolc, 2010. 224 p.

- Víg T. Fogalomjegyzék a TDM-rendszer témakörhöz. Definition index to TDM system. Turizmus Bulletin, 2010, no. 1-2. 119 p.