Factors Affecting Student Engagement in Psychology Undergraduates Studying Online Statistics Courses in Indonesia

Автор: Astri Setiamurti, Rose Mini Agoes Salim, Maridha Normawati, Atikah Ainun Mufidah, Frieda Maryam Mangunsong, Shahnaz Safitri

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.11, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study aimed to assess the influence of students’ intrapersonal factors, namely Academic Intrinsic Motivation (AIM), Perceived Creativity Fostering Teacher Behavior (P-CFTB), Academic Self-Efficacy (ASE), and Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) on student engagement in undergraduate psychology students taking online Statistics courses. A cross-sectional and quantitative design was used from October to December 2022. The data collection procedure used a convenience sampling technique, with questionnaires distributed online (via social media) and offline (via lecturers, the Student Executive Board, and the Association of the Faculty of Psychology from various universities in Indonesia). The research participants were psychology undergraduates who had studied and passed the Statistics courses online, with 671 filling out the questionnaire. The results showed that all students’ intrapersonal factors, namely AIM, P-CFTB, ASE, and SRL, can determine student engagement by 66.9%, with ASE having the highest influence (23.99%) and P-CFTB having the lowest impact (9.78%). Moreover, the correlation value between SRL and SE was r = 0.700, p < 0.001, signifying a robust positive relationship between both variables.

Student engagement, perception of creativity fostering teacher behavior, academic self-efficacy, academic intrinsic motivation, self-regulated learning, online learning

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170200015

IDR: 170200015 | УДК: 159.947.5.072-057.875(594)”2022” | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2023-11-3-359-373

Текст научной статьи Factors Affecting Student Engagement in Psychology Undergraduates Studying Online Statistics Courses in Indonesia

Low student engagement reduces students’ chances of acquiring the necessary talents and skills ( Kuh, 2009 ). Besides students’ ability to apply knowledge in more complex situations ( Primana, 2015 ), students’ memory of learning materials and final grades will also be low ( Staikopoulos et al., 2015 ). Thus, student engagement has become a critical issue in higher education as it significantly influences the quality of learning students acquire ( Staikopoulos et al., 2015 ; Xia et al., 2022 ). Moreover, due to COVID-19, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) worldwide were forced to apply online learning methods. One of the issues often highlighted in online learning methods is closely related to student engagement ( Czerkawski and Lyman, 2016 ; Xia et al., 2022 ). According to previous studies, online learning methods could increase student engagement ( Khusniyah and Hakim, 2019 ; Kuntarto, 2017 ). On the contrary, studies in Indonesia found that online learning methods reduced student engagement ( Fatoni et al., 2020 ; Rusman and Nasution, 2020 ; Sa’diyah, 2021 ).

Student engagement only happens when students involve their feelings and active thinking processes in learning ( Harper and Quaye, 2009 ). Fatoni et al. (2020) found that 100 students from five universities in Indonesia experienced student engagement problems during online learning. This finding is supported by Rusman and Nasution (2020) on UIN Sumatera Utara Medan college students, who found that out of 191 students, only 4.71% had high student engagement during online learning. Furthermore, Sa’diyah (2021) found that students only join online classes to fulfill their attendance but ignore the lessons and do other activities. Thus making them have low student engagement.

Maulana and Iswari (2020) , who analyzed student engagement in calculation-based courses, found that online learning in courses (such as Statistics) causes students to experience stress and difficulty

© 2023 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

understanding the learning material. It made them have low student engagement scores. Moreover, students often view Statistics courses as very mathematical, challenging, and frightening because they use many formulas ( Carpenter and McDonald, 2017 ; Waruwu, Hao and Hia, 2022 ; Zaimil, 2017 ).

Stress regarding statistics courses also occurs in psychology students. Suminta (2016) found psychology students are prone to experience anxiety when studying Statistics. For psychology students, besides being difficult, the Statistics courses are also felt to be unrelated to their future career choices ( Lloyd and Robertson, 2012 ). In fact, those courses are one of the fundamental courses in the psychology program. From developing new therapy techniques to evaluating the effectiveness of strategies, it is a statistical analysis that plays a role in providing an overview and drawing conclusions. Psychologists use statistical analysis to find ways to interpret and draw conclusions from their data ( Watts and Thomas, 2022 ). Given the importance of Statistics for Psychology students, it is urgent to explore the factors that can affect student learning engagement ( Firmansyah, 2017 ; Ulpah, 2009 ).

Several studies exploring factors affecting student engagement in higher education have been conducted. Almarghani and Mijatovic’s (2017) study showed that the lecturers’ role and teaching skills are the most influential factors for student engagement. Elshami et al. (2022) explored that factors such as techno-pedagogical skills, self-directed learning, peer-assisted learning, and collaborative learning are required to support medical and health students’ engagement in online learning. Calabrese et al. (2022) found that frequency and regular meetings, demographic factors such as course of study, expectation, and perception of students, can affect student engagement in personal tutoring schemes.

Student engagement is an interaction process between contextual or learning environment and intrapersonal factors ( Christenson, Reschly and Wylie, 2012 ). Contextual factors include the context of teaching and social relationships (support from teachers, friends, and parents) ( Christenson, Reschly and Wylie, 2012 ; Skinner, Kindermann and Furrer, 2009 ). However, several studies have found that contextual factors are not always able to predict student engagement. In fact, prior research had shown that students’ perceptions of understanding contextual factors were predictive for student engagement ( Christenson, Reschly and Wylie, 2012 ; van Petegem et al., 2007 ). The students’ perceptions of these contextual factors belong to intrapersonal factors, such as how they perceive their learning experience and the source of knowledge ( Christenson, Reschly and Wylie, 2012 ; Raviv et al., 2003 ).

Various intrapersonal factors have been reported to influence student engagement, such as academic self-efficacy (ASE) ( Helsa and Lidiawati, 2021 ; Pramisjayanti and Khoirunnisa, 2022 ; Zhen et al., 2017 ), academic intrinsic motivation (AIM) ( Dierendonck et al., 2023 ; Myint and Khaing, 2020 ), and self-regulated learning (SRL) ( Lidiawati and Helsa, 2021 ; Setiani and Wijaya, 2020 ). ASE is a student’s determination and behavior toward assignments and the educational process ( Chang and Chien, 2015 ; Zhen et al., 2017 ). Students with low ASE showed more indifference and low engagement in learning ( Bassi et al., 2007 ). In contrast, according to meta-analysis studies ( Chang and Chien, 2015 ), students with high ASE scores had higher student engagement.

AIM is also strongly related to engagement. This is proven by Dierendonck et al. (2023) , who found that students who study for intrinsic reasons tend to be more focused and actively engaged because they enjoy learning. The next intrapersonal factor that is positively related to student engagement is selfregulated learning (SRL) ( Lidiawati and Helsa, 2021 ; Setiani and Wijaya, 2020 ). To improve academic achievement, students must have self-regulated learning skills to stay engaged in lectures, especially online learning.

Additionally, Primana (2015) found that college students in Indonesia perceive their lecturers as the primary source of knowledge. Students’ perceptions of their lecturers also significantly impact student engagement ( Pachler, Kuonath and Frey, 2019 ; Primana, 2015 ). Furthermore, Lawton and Taylor (2020) investigated college student perceptions of engagement and teaching strategies in the Introduction to Statistics course. They discovered activities that increased student engagement in online learning, such as when lecturers gave simulation-based instructions and asked students to carry out group discussions and independent study. On the other hand, students identified low engagement when there were no hands-on activities and students were only taking notes and listening during online classes.

A strategy and consistent effort of lecturers to encourage students to use their knowledge to think independently and flexibly by using new approaches to solve problems is called Creativity Fostering Teacher Behavior (CFTB) ( Cropley, 1997 ). Based on Lawton and Taylor (2020) findings, we concluded that the concept of creativity fostering teacher behavior (CFTB) was strongly related to how students perceived the teaching strategies used by lecturers in the study. CFTB is a teaching strategy that aims to develop students’ creative thinking or behavior” ( Jeffrey and Craft, 2004 ). The CFTB concept also aligns with learning material in Statistics courses, which require flexible and creative thinking to solve complex calculation problems ( Grégoire, 2016 ).

Up until now, most studies involving the CFTB variable measured CFTB from teachers’ or lecturers’ perceptions ( Huang, 2022 ; Karwowski, Gralewski and Szumski, 2015 ; Palaniappan, 2009 ; Varatharaj, 2018 ); pre-service teachers ( Katz-Buonincontro, Perignat and Hass, 2020 ; Kim et al., 2019 ; Orr and Kukner, 2015 ); and the effect of CFTB on students’ creativity ( Bell et al., 2014 ; Hafizi and Kamarudin, 2020 ; Mao et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ). Meanwhile, the research that examined the relationship and role of students’ perceptions of CFTB on student engagement is still limited. Even though, since 2000, Soh has suggested that the research on CFTB should be measured based on student perceptions. Students’ perceptions of CFTB in this study will be called perceived CFTB or P-CFTB.

As previous studies have shown, student engagement is more influenced by intrapersonal factors. In addition, as Rusman and Nasution (2020) stated, there is a need for research that explores the factors affecting student engagement in an online learning context. Therefore, it is vital to conduct exploratory research on students’ intrapersonal factors by assessing the role of these factors in learning engagement in online Statistics courses. Rodgers (2008) also said that to increase teaching effectiveness and academic achievement, HEIs should consider developing online teaching strategies that encourage greater student engagement.

Although some studies have investigated the role of AIM ( Cayubit, 2022 ; Giesbers et al., 2013 ; Gettle, 2022 ), ASE ( Chang and Chien, 2015 ; Helsa and Lidiawati, 2021 ; Pramisjayanti and Khoirunnisa, 2022 ; Zhen et al., 2017 ), SRL ( Lidiawati and Helsa, 2021 ; Nurfitri and Aslamawati, 2021 ; Setiani and Wijaya, 2020 ; Utami and Aslamawati, 2021 ) that influence student engagement, however their role in undergraduate psychology students taking online Statistics courses are still limited. Furthermore, empirical research on CFTB is limited to teacher/lecturer ( Huang, 2022 ; Karwowski, Gralewski and Szumski, 2015 ; Palaniappan, 2009 ; Varatharaj, 2018 ) and pre-service teacher/lecturer ( Katz-Buonincontro, Perignat and Hass, 2020 ; Kim et al., 2019 ; Orr and Kukner, 2015 ), so few studies examine student perceptions of CFTB. Therefore, the study hypothesizes that academic intrinsic motivation, perceived creativity fostering teacher behavior, academic self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning simultaneously can determine student engagement in undergraduate psychology students taking online Statistics courses.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study used a cross-sectional design from October to December 2022. The following criteria were emphasized for the selection of participants: (1) The psychology undergraduates need to have studied and passed the Statistics course through the online learning method, (2) The students should follow the appropriate time interval for studying the course, and (3) The period used by the undergraduates to complete the research questionnaire should not be more than three semesters. It has been done since the implementation of online learning methods by most HEIs in the last three semesters during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data collection procedure used a convenience sampling technique, with questionnaires distributed online (via social media) and offline (via lecturers, the Student Executive Board, and the Association of the Faculty of Psychology from various universities in Indonesia).

Table 1

Demographic Data of Participants (N= 533)

|

Demography |

n |

% |

|

|

Gender |

Female |

435 |

81.61 |

|

Male |

98 |

18.39 |

|

|

Age (year) |

18 |

32 |

6.00 |

|

19 |

232 |

43.53 |

|

|

20 |

199 |

37.34 |

|

|

21 |

48 |

9.01 |

|

|

>21 |

22 |

4.13 |

|

|

Semester |

3 |

322 |

60.41 |

|

4 |

3 |

0.56 |

|

|

5 |

183 |

34.33 |

|

|

7 |

21 |

3.94 |

|

|

8 |

1 |

0.19 |

|

|

>8 |

3 |

0.56 |

|

|

University Location (Province) |

Aceh |

1 |

0.19 |

|

Banten |

36 |

6.75 |

|

|

DI Yogyakarta |

9 |

1.69 |

|

|

DKI Jakarta |

219 |

41.09 |

|

|

West Java |

163 |

30.58 |

|

|

Central Java |

9 |

1.69 |

|

|

East Java |

63 |

11.82 |

|

|

South Kalimantan |

5 |

0.94 |

|

|

South Sulawesi |

3 |

0.56 |

|

|

South Sumatera |

22 |

4.13 |

|

|

North Sumatera |

3 |

0.56 |

|

Participants

The research participants were psychology undergraduates who had studied and passed the Statistics courses via online learning, with 671 filling out the questionnaire. However, only 533 participants met the selection criteria and were spread from 11 provinces in Indonesia, with the majority originating from DKI Jakarta (40.68%). Most of the participants were 19 years old (43.55%), female (81.54%), and 3rd-semester students (59.86%). A detail of participants’ demographic data of participants can be seen in Table 1.

Research Instrument

This research used five research instruments, namely (1) The University Students’ Engagement Inventory (USEI) by Morocco et al. (2016) , (2) The Creativity Fostering Teacher Index (CFTIndex) by Soh (2000) , (3) The Indonesian College Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (CASES) by Ifdil et al. (2019) , (4) The Online Self-regulated Learning Questionnaire (OSLQ) by Mutiara and Rifameutia (2021) , and (5) The Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) by Marvianto and Widhiarso (2019) . Each instrument was tested for reliability through the Cronbach Alpha and CRiT values, with validity analyzed by using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The fit index used as a criterion for the cut-off value was also CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08, and SRMR < 0.08 ( Hu and Bentler, 1999 ; Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger and Müller, 2003 ).

Students’ Engagement (SE)

The Indonesian version of the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI) instrument by Morocco et al. (2016) was adopted to measure students’ engagement. This instrument consisted of three dimensions (cognitive, behavioral, and emotional engagement), each with five items. These items were then assessed using a 6-point Likert scale, with 1 to 6 emphasizing never to always, respectively. The total value was counted by adding up the scores of each item. An example of a sample item is, “I usually do my homework on time.” The Indonesian version of the USEI had a reliability value of Cronbach’s α = 0.862, signifying that the instrument was reliable (Kaplan and Saccuzzo, 2017). All items also showed good internal validity, with CRiT values ranging from 0.261-0.647 (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). In addition, CFA showed that the USEI was valid due to meeting the goodness of fit criteria with chi-square = 3.72 (X2 = 320.355; df = 86, p < 0.001), CFI = 0.905, RMSEA = 0.072, and SRMR = 0.067.

Academic Intrinsic Motivation (AIM)

AIM was measured through the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) by taking three dimensions of Intrinsic Motivation from Vallerand et al. (1992) , which has been adapted into the Indonesian version by Marvianto and Widhiarso (2019) . It consisted of three factors, namely IM-to know, IM-toward accomplishment, and IM-to experience stimulation, each having four items. Using a 6-point Likert scale, namely 1 (do not correspond at all) to 6 (corresponds exactly), the total scores of AIM were obtained by adding up the scores of all items. The sentences in several items were also adjusted, such as the replacement of ‘school’ with ‘college’ to fit the research context. For example, a sample item stated, “Because I experience pleasure and satisfaction while learning new things.” From the results, AMS had a reliability value of Cronbach’s α = 0.896 and CRIT = 0.526 - 0.685. CFA also showed that AMS was valid due to meeting the goodness of fit criteria with chi-square = 4.17 (X2= 204.624; df = 49, p < 0.001), CFI = 0.945, RMSEA = 0.077, and SRMR = 0.040.

Perceived Creativity Fostering Teacher Behavior (P-CFTB)

Researchers adapted the Creativity Fostering Teacher Index (CFTIndex) instrument by Soh (2000) into the Indonesian version to measure lecturer creativity fostering from a student perspective, named Perceived CFTIndex (P-CFTIndex). This instrument initially contained 45 items, which was reduced to 27 after being adapted based on the CFTB-Index procedure by Lee and Kemple (2014) . It still consisted of nine dimensions, each containing three items in the Indonesian version. Each item was also assessed using a 6-point Likert scale, namely 1 (never) to 6 (always). Moreover, the total score was obtained by adding up the scores of each item, with a sample example indicating the following, “Lecturer encourages me to try out what I have learned in different situations.” From the results, P-CFTIndex had a reliability value of Cronbach’s α = 0.944, signifying that the instrument was reliable. All items also showed good internal validity, with the CRiT values ranging from 0.357 to 0.713. In addition, CFA showed that P-CFTB measuring instrument was valid because of meeting the goodness of fit criteria with chi-square = 3.25 (X2 = 936,660; df = 288, p < 0.001), CFI = 0.904, RMSEA = 0.065, and SRMR = 0.047.

Academic Self-Efficacy (ASE)

ASE was measured using the Indonesian CASES version by Ifdil et al. (2019) , adapted from Owen and Froman (1988) . This instrument initially contained 33 items, which were then reduced to 17 items and categorized into three dimensions. These dimensions included technical skills (5 items), overt social situation (6 items), and cognitive operation (6 items). The total score was calculated by adding up the scores of all items. Each item was also assessed by using a 6-point Likert scale, namely 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with a sample example presented as follows, “I master most of the lecture materials having many elements of calculation.” From the results, CASES had a reliability value of Cronbach’s α = 0.914, with CFA emphasizing its validity due to meeting the goodness of fit criteria with chi-square = 2.36 (X2 = 1092.270; df = 462, p < 0.001), CFI = 0.905, RMSEA = 0.079, and SRMR = 0.054.

Self-Regulated Learning (SRL)

Online Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire (OSLQ) was used to measure SRL ( Barnard-Brak, Paton and Lan, 2010 ) and adapted to the Indonesian version by Mutiara and Rifameutia (2021) . This instrument initially contained 24 items, which were then reduced to 21 elements after translation and categorized into six dimensions. These dimensions included environmental structuring, goal-setting, time management, help-seeking, task strategies, and self-evaluation, which consisted of 4, 5, 3, 2, 4, and 4 items, respectively. The items were also assessed using a 6-point Likert scale, namely 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Moreover, the total score was obtained by adding up the scores of each item, with the example of a sample stating the following, “I prepare questions before joining an online lecture-discussion session.” OSLQ had a reliability value of Cronbach’s α = 0.918 and CRIT = 0.377 -0.673. CFA also showed that the instrument was valid due to meeting the goodness of fit criteria with chi-square = 3.63 (X2 = 626.008; df = 172, p < 0.001), CFI = 0.906, RMSEA = 0.070, and SRMR = 0.055.

Research Procedure and Data Analysis

The procedures and instruments of this study were carefully reviewed by the Faculty of Psychology ethics committee under number 136/FPsi.Komite Etik/PDP.04.00/2022. The adaptation of measuring instruments into Indonesian versions (P-CFTIndex and USEI) was also carried out regarding the procedure of Beaton et al. (2000) , which contained five stages, namely (1) translation, (2) synthesis, (3) back translation, (4) expert assessment, and (5) data collection. In addition, the results were analyzed by performing multiple regression through JASP software version 0.164.

Results

Statistic Descriptive Analysis

Pearson’s test was carried out to determine the correlation of each variable, as described in Table 2. The results showed a moderate correlation among the variables, with ASE and SE showing the most vital relationship than other independent determinants (r = 0.714, p <.001). However, P-CFTB and SE exhibited a moderate correlation between the independent and the dependent variables (r = 0.593, p <.001), with P-CFTB and AIM portraying the weakest relationship (0.468).

Table 3 explains the descriptive analysis of each variable, where the range of values included 45-90, 37-72, 77-162, 90-193, and 45- 126 for SE, AIM, P-CFTB, ASE, and SRL, respectively. Based on the results, the Mean/Standard Deviation values were high for SE, AIM, and P-CFTB at 69.46/9.17, 58.20/7.72, and 126.47/18.18, respectively. Meanwhile, the Mean/Standard Deviation values were in the moderate category for ASE and SRL at 71.90/12.63 and 88.92/16.18, respectively.

Table 2.

Variables Intercorrelation

|

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 4 |

5 |

|

1.SE |

— |

|||

|

2. AIM |

0.621*** |

— |

||

|

3. P-CFTB |

0.593*** |

0.468*** |

— |

|

|

4.ASE |

0.714*** |

0.505*** |

0.495*** — |

|

|

5. SRL |

0.700*** |

0.503*** |

0.572*** 0.676*** |

— |

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

SE = Students’ Engagement, AIM = Academic Intrinsic Motivation, P-CFTB = Perceived Creative Fostering Teacher Behavior, ASE = Academic Self-Efficacy, SRL = Self-Regulated Learning

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistic

|

Variables |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

|

1.SE |

533 |

69.46 |

9.17 |

45.00 |

90.00 |

|

2. AIM |

533 |

58.20 |

7.72 |

37.00 |

72.00 |

|

3. P-CFTB |

533 |

126.47 |

18.18 |

77.00 |

162.00 |

|

3.ASE |

533 |

71.90 |

12.63 |

90.00 |

193.00 |

|

4. SRL |

533 |

88.92 |

16.18 |

45.00 |

126.00 |

Note: SE = Students’ Engagement; AIM = Academic Intrinsic Motivation; P-CFTB = Perceived Creative Fostering Teacher Behavior; ASE = Academic Self-Efficacy; SRL = Self-Regulated Learning.

Table 4.

Participants’ Categorization of Each Variable (N= 533)

|

Variable |

Category |

|||

|

Low |

Moderate |

High |

||

|

SE |

score range |

<40 |

40 < x < 65 |

>65 |

|

n |

0 |

157 |

376 |

|

|

% |

00.00 |

29.46 |

70.54 |

|

|

AIM |

score range |

<32 |

32 < x < 52 |

>52 |

|

n |

0 |

101 |

432 |

|

|

% |

00.00 |

18.95 |

81.05 |

|

|

P-CFTB |

score range n % |

<72 0 00.00 |

72 162 30.39 |

>117 371 69.61 |

|

ASE |

score range n % |

<45.3 11 2.06 |

45.3 < x < 73.7 283 53.09 |

>73.7 239 44.84 |

|

SRL |

score range |

<56 |

56 < x < 91 |

>91 |

|

n |

12 |

280 |

241 |

|

|

% |

02.25 |

52.53 |

45.22 |

|

Note: SE = Students’ Engagement; AIM = Academic Intrinsic Motivation; P-CFTB = Perceived Creative Fostering Teacher Behavior; ASE = Academic Self-Efficacy; SRL = Self-Regulated Learning.

Table 4 presents the participant categorization of each variable, where the majority of samples were observed in the high category for SE (70.54%), AIM (81.05%), ASE (50.47%), and P-CFTB at 70.54%, 81.05%, 50.47%, and 69.61%, respectively. However, most participants on the SRL variable were included in the medium category at 52.53%.

Multiple Linear Regression Prerequisite Test

Multiple regression analysis was employed to determine whether the research model’s four independent variables (IVs) collectively possess predictive abilities for student engagement. When assessing multiple linear regression models, it is crucial to meet at least four prerequisite tests: multicollinearity, data linearity, homoscedasticity, and multivariate normality ( Osborne and Waters, 2002 ).

Multicollinearity Test

The multicollinearity test was applied to gauge the degree of correlation among the independent variables. Midi, Sarkar and Rana (2010) stipulated that there is no multicollinearity when the tolerance value is >0.1 and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) is <10. Table 5 demonstrates the tolerance values for each variable are >0.1, and the VIF values for all variables are <10, signifying that the model meets the multicollinearity requirement.

Table 5.

Multicollinearity Test Result

|

Collinearity Statistics |

|||

|

Model |

Tolerance |

VIF |

|

|

Hi |

(Intercept) |

||

|

AIM |

0.664 |

1.506 |

|

|

P-CFTB |

0.620 |

1.614 |

|

|

ASE |

0.499 |

2.005 |

|

|

SRL |

0.456 |

2.195 |

|

|

a. Dependent variable: Student Engagement |

|||

Data Linearity Test

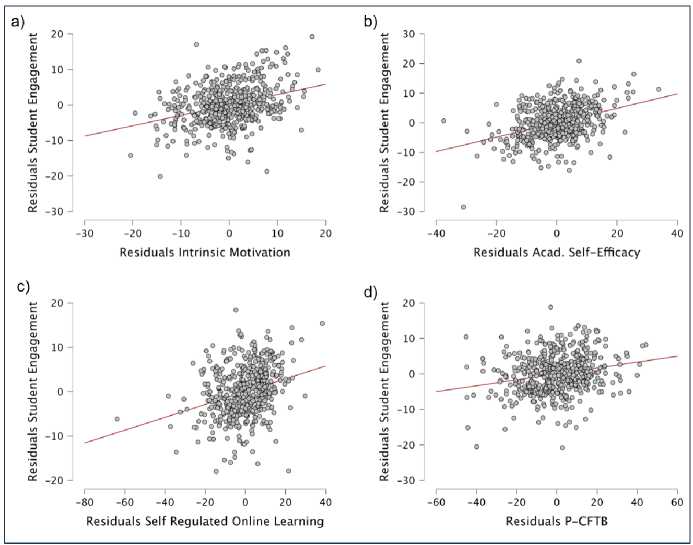

The data linearity test establishes a linear relationship among the independent variables ( Hayes, 2015 ). It is tested by examining the scatterplot between the DV and each IV. The outcomes of the linearity test, illustrated in Figure 1 below, indicate the presence of a linear relationship between the dependent and independent variables, thereby fulfilling the linearity assumption.

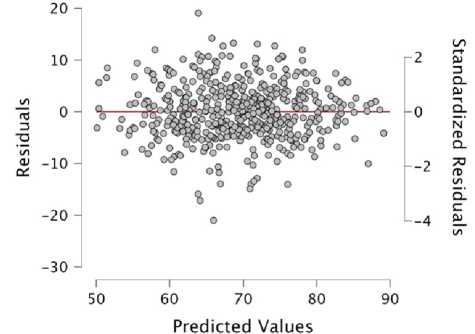

Homoscedasticity Test

A scatterplot of residuals against predicted values is used to evaluate homoscedasticity ( Hariyanto, Triyono and Köhler, 2020 ). Figure 2, presented below, illustrates the data distribution pattern, signifying that the assumption of homoscedasticity has been met.

Figure 1. Data Linearity Test Results

Figure 2. Homoscedasticity Test Result

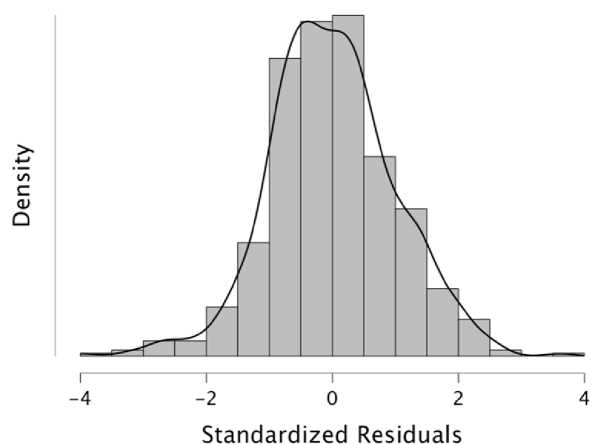

Multivariate Normality Test

The multivariate normality test is used to verify the normal distribution of data. Figure 3 indicates that the residuals conform to a normal distribution, affirming that the model meets the multivariate normality assumption.

Figure 3. Normal Distribution Curve

Multiple Linear Regression Results

Multiple linear regression was conducted after all the prerequisite tests showed that the results met the requirement. Table 6 below shows that F = 267.358; p < 0.001, meaning that AIM, P-CFTB, ASE, and SRL can significantly determine student engagement. This means the research hypothesis is accepted. Table 6 also shows that multiple linear regression’s coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.669. Based on the guidelines for interpreting the coefficient of determination (R2) by Sarjana, Hayati and Wahidaturrahmi (2020) , 0.669 is included in the strong influence category. This means that AIM, P-CFTB, ASE, and SRL significantly predict learning engagement with an influence contribution of 66.90%, with the remaining 33.10% influenced by variables not included in this study.

Table 6.

Multiple Linear Regression Model Summary

|

Model |

R |

R2 |

Adjusted R2 |

RMSE |

R2Change |

FChange |

df1 |

df2 |

P |

|

Ho |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

9.168 |

0.000 |

0 |

532 |

||

|

Hi |

0.818 |

0.669 |

0.667 |

5.291 |

0.669 |

267.358 |

4 |

528 |

<.001 |

Table 7.

Coefficients

Note: SE = Students’ Engagement; AIM = Academic Intrinsic Motivation; P-CFTB = Perceived Creative Fostering Teacher Behavior; ASE = Academic Self-Efficacy; SRL = Self-Regulated Learning.

From Table 7 above, the relationship between variables can be seen in the following equation: Y = α + β1X1 + β2X2 + β3X3 + β4X4 + e

Y (SE) = 11.539 + 0.292*AIM + 0.083*PCFTB + 0.244*ASE + 0.145*SRL + e

From the multiple linear regression equation above, it can be explained as follows:

-

a) The constant (α) has a positive value of 11.539. This shows that if all independent variables are worth 0, the base value of student engagement is 11.539.

-

b) For every percentage increase in AIM, student engagement increases by 0.292, assuming other independent variables remain constant.

-

c) For every percentage increase in P-CFTB, student engagement increases by 0.083, assuming other independent variables remain constant.

-

d) For every percentage increase in ASE, student engagement increases by 0.244, assuming other independent variables remain constant.

-

e) For every percentage increase in SRL, the student engagement increases by 0.145, assuming other independent variables remain constant.

To determine the amount of influence of each independent variable on the dependent variable partially, we used the Beta*Zero Order formula. Based on the formula, it is known that the most significant influence comes from the ASE, with an influence contribution of 23.99%. This is followed by the SRL, which contributes an influence of 17.85%, the AIM of 15.27%, and the P-CFTB of 9.78%.

Discussions

This study provides an overview of the interaction between intrapersonal factors, namely Academic Intrinsic Motivation (AIM), Academic Self-Efficacy (ASE), Self-Regulated Learning (SRL), and Perceived Creativity Fostering Teacher Behavior (P-CFTB), in predicting student engagement in undergraduate psychology students taking online statistics courses. Hypotheses were examined to test whether these intrapersonal factors simultaneously affect student engagement. The results found that the four independent variables studied (AIM, ASE, SRL, and P-CFTB) significantly determined student engagement, with a contribution of 66.9%. Based on the research results above, it can be concluded that the study’s hypothesis is confirmed. These results support findings in previous studies that state that intrapersonal factors are the main factor in predicting student engagement ( Christenson, Reschly and Wylie, 2012 ; van Petegem et al., 2007 ).

Furthermore, we examined the power contribution of each independent variable to student engagement. The results showed that AIM significantly predicted SE among psychology undergraduates in online Statistics courses (R2=15.27%; p<0.001). The results supported Gettle (2022) , where AIM significantly affected SE in psychology undergraduate students. The findings of this study also support the findings reported by Giesbers et al. (2013) and Gettle (2022) , who discovered that intrinsic motivation is closely linked to student engagement in online learning by utilizing technologies in applications, such as chat, webcams, and microphones. The academic achievement of students is also strongly related to student engagement through the usage of these tools.

Furthermore, ASE had the most significant influence on SE at 23.99%, compared to other variables. The findings support Warwick’s statement ( Warwick’s, 2008 ) that student self-efficacy predicts student involvement. Students who have confidence that they are capable will be more persistent in facing difficulties. On the other hand, students with low self-efficacy will feel helpless and less persistent in completing complex tasks. In line with this, research by Helsa and Lidiawati (2021) found that self-efficacy had an effect of 36.9% on student learning engagement. Pramisjayanti and Khoirunnisa’s (2022) study also found that self-efficacy influenced 64.9% of student engagement in online learning.

The results also revealed that SRL significantly affected SE at an impact level of 17.85%. This was not in line with Lidiawati and Helsa (2021) , where a more significant effect of SRL on SE was observed at 55.9%. Nurfitri and Aslamawati (2021) found that self-regulated learning has a 57% impact on student engagement. A similar result was also found in Utami and Aslamawati (2021) , who explained that the effect of self-regulated learning was 52.8% on student engagement. These differences emphasized specific research measuring students’ SRL abilities when learning Statistics courses.

Moreover, this study found that student perceptions of creativity fostering teacher behavior (P-CFTB) can predict student engagement in online learning, with a 9.78% contribution. Students’ perceptions of teaching strategies that encourage creativity, such as independent learning, opportunities to develop and share ideas, divergent thinking, reflection, learning opportunities with a variety of materials and conditions, and support for overcoming failures, play a significant role in predicting student engagement in students who take online Statistics courses. In line with previous research has found that students’ attitudes and beliefs about lecturers influence student engagement in the classroom ( Christenson, Reschly and Wylie,

2012 ; Pachler, Kuonath and Frey, 2019 ; Primana, 2015 ; Raviv et al., 2003 ).

Solving statistical problems requires the ability to think creatively. Therefore, creative teaching strategies (teaching for creativity) will also influence students’ attitudes toward the statistics learning process, and attitudes toward learning significantly positively affect learning achievement ( Hu, Deng and Guan, 2016 ). This finding also expands on research by Golder (2018) and Lawton and Taylor (2020) regarding student perceptions of lecturer behavior. Golder (2018) found that students’ perceptions of their lecturers significantly related to their attitudes toward learning. Furthermore, Lawton and Taylor (2020) found that students’ perceptions of independent teaching and learning strategies can increase student engagement.

Additionally, this research found that ASE strongly and significantly correlated with SE in statistics courses (r = 0.714, p < 0.001). This was not in line with this previous research; Fan and Williams (2010) showed that students’ ASE in mathematics and English significantly correlated with engagement in these subjects. The results confirmed that the correlation between these variables was more substantial in English lessons (r = 0.54) than in mathematics (r = 0.49). It means that in this research, students will be more engaged in the learning process if they believe they can learn.

Furthermore, the correlation value between SRL and SE was r = 0.700, p < 0.001, signifying a robust positive relationship between both variables. The result differs from Setiani and Wijaya (2020) , who reported a weak positive correlation between both variables (r = 0.262). However, the effect aligned with Lidiawati and Helsa (2021) , who found a strong positive correlation between SRL and SE (r = 0.748). The strong positive correlation can happen because, according to Bond and Bedenlier (2019) , cognitive engagement and the ability towards self-regulation are highly associated. Anjarwati and Sa’adah (2021) also explained that student engagement in the period of online learning is known to increase student participation from students’ cognitive and behavioral aspects.

Conclusions

This study found students’ intrapersonal factors, namely Academic Intrinsic Motivation (AIM), Academic Self-Efficacy (ASE), Self-Regulated Learning (SRL), and Perceived Creativity Fostering Teacher Behavior (P-CFTB), can determine student engagement by 66.9%, with ASE having the highest influence (23.99%) and P-CFTB having the lowest impact (9.78%). It also found that most participants belong to the high SE, P-CFTB, AIM, ASE, and moderate SRL categories. There was also a moderate correlation among the variables, with ASE and SE showing the most substantial relationship (r = 0.714, p <.001). However, P-CFTB and SE exhibited a moderate correlation between the independent and the dependent variables (r = 0.593, p <.001), with P-CFTB and AIM portraying the weakest relationship (0.468). This indicated that the strongest and weakest correlation values were found between ASE-SE and P-CFTB-SE, respectively. The results also showed that P-CFTB, AIM, ASE, and SRL increased SE among Psychology undergraduates taking online Statistics courses.

The limitation of this study is the high-value questionnaire items, causing participants to experience fatigue during the fill-out process. The variables also promoted a high social desirability tendency. Subsequently, a delay was found between filling out the questionnaire and completing the Statistics courses. For example, when filling out the data instrument, students were already in semester 5, despite the last Statistics courses conducted in semester 3.

According to the research, students’ intrapersonal factors in online Statistics courses significantly impact their level of engagement. Therefore, statistics lecturers are expected to create a learning atmosphere that enhances students’ intrapersonal factors, namely AIM, P-CFTB, ASE, and SRL. The research implies that our study can pinpoint the contribution of intrapersonal factors that affect student engagement, enabling statistics lecturers to give these internal factors more attention.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., R.M.A.S, M.N., A.A.M., F.M.M., and S.S.; methodology, A.S., R.M.A.S, M.N., A.A.M., F.M.M., and S.S.; formal analysis, A.S., R.M.A.S, M.N., A.A.M., F.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., M.N., and A.A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.S., M.N., and A.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Список литературы Factors Affecting Student Engagement in Psychology Undergraduates Studying Online Statistics Courses in Indonesia

- Abd-Elmotaleb, M., & Saha, S. K. (2013). The role of academic self-efficacy as a mediator variable between perceived academic climate and academic performance. Journal of Education and Learning, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v2n3p117 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v2n3p117

- Almarghani, E. M. & Mijatovic, I. (2017). Factors affecting student engagement in HEIs - It is all about good teaching. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(8), 940-956, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1319808 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1319808

- Anjarwati, R., & Sa’adah, L. (2021). Student learning engagement in the online class. EnJourMe (English Journal of Merdeka) : Culture, Language, and Teaching of English, 6(2), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.26905/enjourme.v6i2.6128 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26905/enjourme.v6i2.6128

- Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S.-L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005

- Barnard-Brak, L., Paton, V. O., & Lan, W. Y. (2010). Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(1), 61-80. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i1.769 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i1.769

- Bassi, M., Steca, P., Fave, A. D., & Caprara, G. V. (2007). Academic self-efficacy beliefs and quality of experience in learning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(3), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9069-y DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9069-y

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spines, 25(24), 3186–3191. https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/citation/2000/12150/guidelines_for_the_process_of_cross_cultural.14.aspx DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

- Bell, H., Limberg, D., Jacobson, L., & Super, J. T. (2014). Enhancing Self-Awareness Through Creative Experiential-Learning Play-Based Activities. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 9(3), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2014.897926 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2014.897926

- Bond, M., & Bedenlier, S. (2019). Facilitating student engagement through educational technology: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2019(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.528 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.528

- Calabrese, G., Leadbitter, D. M., Trindade, N. D. S. M. D., Jeyabalan, A., Dolton, D., & ElShaer, A. Personal tutoring scheme: Expectations, perceptions and factors affecting students’ engagement. Frontiers in Education, 6, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.727410 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.727410

- Carpenter, T. P., & McDonald, J. (2017, May 1). Teaching (and learning) psychology statistics in an age of math anxiety. American Psychological Association. https://psychlearningcurve.org/psychology-statistics/

- Cayubit, R. F. O. (2022). Why learning environment matters? An analysis on how the learning environment influences the academic motivation, learning strategies and engagement of college students. Learning Environments Research, 25(2), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09382-x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09382-x

- Chang, D., & Chien, W. cheng. (2015). Determining the relationship between academic self-efficacy and student engagement by meta-analysis. Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Education Reform and Modern Management, 142–145. https://doi.org/10.2991/ermm-15.2015.37 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2991/ermm-15.2015.37

- Christenson, S., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7

- Cropley, A. J. (1997). Fostering creativity in the classroom: General principles. In M. Runco (Ed.), The creativity research handbook (Vol. 1, Issue Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press., pp. 83– 114). Hampton Press. http://scottbarrykaufman.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Runcohandbookchapter.pdf

- Czerkawski, B. C., & Lyman, E. W. (2016). An instructional design framework for fostering student engagement in online learning environments. TechTrends, 60(6), 532–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0110-z DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0110-z

- Dierendonck, C., Tóth-Király, I., Morin, A. J. S., Kerger, S., Milmeister, P., & Poncelet, D. (2023). Testing associations between global and specific levels of student academic motivation and engagement in the classroom. The Journal of Experimental Education, 91(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2021.1913979 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2021.1913979

- Elias, S. M., & MacDonald, S. (2007). Using past performance, proxy efficacy, and academic self-efficacy to predict college performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(11), 2518–2531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00268.x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00268.x

- Elshami, W., Taha, M. H., Abdalla, M., E., Abuzaid, M., Saravanan, C., & Al Kawas, S. (2022). Factors that affect student engagement in online learning in health professions education. Nurse Education Today, 110, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105261 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105261

- Fan, W., & Williams, C. M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903353302 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903353302

- Fatoni, Arifiati, N., Nurkhayati, E., Nurdiawati, E., Pamungkas, G., Adha, S., Purwanto, A., Julyanto, O., & Azizi, E. (2020). University students online learning system during Covid-19 pandemic: Advantages, constraints and solutions. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 11(7), 570–576. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3986850

- Firmansyah, M. A. (2017). Analisis hambatan belajar mahasiswa pada mata kuliah statistika [Analysis of student learning barriers in statistics courses]. Jurnal Penelitian Dan Pembelajaran Matematika, 10(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.30870/jppm.v10i2.2036 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30870/jppm.v10i2.2036

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

- Gettle, C. M. (2022). How personality traits and academic motivation affect engagement in synchronous online University courses [Undergraduate Thesis]. University of Regina. https://instrepo-prod.cc.uregina.ca/handle/10294/14894

- Giesbers, B., Rienties, B., Tempelaar, D., & Gijselaers, W. (2013). Investigating the relations between motivation, tool use, participation, and performance in an e-learning course using web-videoconferencing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.09.005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.09.005

- Golder, J. (2018). Students’ perceptions on teacher behaviour at college level. International Education & Research Journal (IERJ), 4(6), 13–14. https://www.academia.edu/download/65833349/05_IERJ20188551152783_Print_Joydip_Golder.pdf

- Grégoire, J. (2016). Understanding creativity in mathematics for improving mathematical education. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 15(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.15.1.24 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.15.1.24

- Hafizi, M. H. M., & Kamarudin, N. (2020). Creativity in mathematics: Malaysian perspective. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(3 3C), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081609 DOI: https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081609

- Hariyanto, D., Triyono, M. B., & Köhler, T. (2020). Usability evaluation of personalized adaptive e-learning system using USE questionnaire. Knowledge Management and E-Learning, 12(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2020.12.005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2020.12.005

- Harper, S. R., & Quaye, S. J. (2009). Student engagement in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and practical approaches for diverse populations. In S. R. Harper & S. J. Quaye (Eds.), Student engagement in higher education. Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203894125

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate behavioral research, 50(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Helsa, H., & Lidiawati, K. R. (2021). Peran self-efficacy terhadap student engagement pada mahasiswa dalam pandemi COVID-19. Psibernetika, 14(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.30813/psibernetika.v14i2.2887

- Hu, M., Li, H., Deng, W., & Guan, H. (2016). Student engagement: One of the necessary conditions for online learning. 2016 International Conference on Educational Innovation through Technology (EITT), 122–126. https://doi.org/10.1109/EITT.2016.31 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/EITT.2016.31

- Huang, X. (2022). Constructing the associations between creative role identity, creative self-efficacy, and teaching for creativity for primary and secondary teachers. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000453 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000453

- Ifdil, I., Bariyyah, K., Dewi, A. K., & Rangka, I. B. (2019). The College Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (CASES); An Indonesian validation to measure the self-efficacy of students. Jurnal Kajian Bimbingan Dan Konseling, 4(4), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.17977/um001v4i42019p115 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17977/um001v4i42019p115

- Jeffrey, B., & Craft, A. (2004). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity: Distinctions and relationships. Educational Studies, 30(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569032000159750 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569032000159750

- Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2017). Psychological testing: Principles, applications, and issues. Cengage Learning.

- Karwowski, M., Gralewski, J., & Szumski, G. (2015). Teachers’ Effect on Students’ Creative Self-Beliefs Is Moderated by Students’ Gender. Learning and Individual Differences, 44, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.10.001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.10.001

- Katz-Buonincontro, J., Perignat, E., & Hass, R. W. (2020). Conflicted epistemic beliefs about teaching for creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 36(January). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100651 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100651

- Khusniyah, N. L., & Hakim, L. (2019). Efektivitas pembelajaran berbasis daring: Sebuah bukti pada pembelajaran bahasa Inggris [The effectiveness of online learning: An evidence on English language learning]. Jurnal Tatsqif, 17(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.20414/jtq.v17i1.667 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20414/jtq.v17i1.667

- Kim, D. J., Bae, S. C., Choi, S. H., Kim, H. J., & Lim, W. (2019). Creative character education in mathematics for prospective teachers. Sustainability, 11(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061730 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061730

- Kuh, G. D. (2009). What student affairs professionals need to know about student engagement. Journal of College Student Development, 50(6), 683–706. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0099 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0099

- Kuntarto, E. (2017). Keefektifan model pembelajaran daring dalam perkuliahan bahasa Indonesia di perguruan tinggi [The effectiveness of online learning in Indonesian language course in higher education]. Journal Indonesian Language Education and Literature, 3(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.24235/ileal.v3i1.1820

- Lawton, S., & Taylor, L. (2020). Student perceptions of engagement in an introductory statistics course. Journal Of Statistics Education, 2020(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2019.1704201 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2019.1704201

- Lee, I. R., & Kemple, K. (2014). Preservice teachers’ personality traits and engagement in creative activities as predictors of their support for children’s creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 26(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2014.873668 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2014.873668

- Lidiawati, R. K., & Helsa, H. (2021). Pembelajaran online selama pandemi Covid-19: Bagaimana strategi pembelajaran mandiri dapat mempengaruhi keterlibatan siswa [Online learning during Covid-19: How self-learning strategies can affect student engagement]. Jurnal Psibernetika, 14(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.30813/psibernetika.v14i1.2570

- Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308223 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308223

- Lloyd, S. A., & Robertson, C. L. (2012). Screencast tutorials enhance student learning of statistics. Teaching of Psychology, 39(1), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311430640 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311430640

- Mao, J., Chen, J., Ling, Y., & Huebner, E. S. (2020). Impact of Teachers’ Leadership on the Creative Tendencies of Students: The Mediating Role of Goal-orientation. Creativity Research Journal, 32(3), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1821569 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1821569

- Maroco, J., Maroco, A. L., Campos, J. A. D. B., & Fredricks, J. A. (2016). University student’s engagement: development of the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI). Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 29(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0042-8 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0042-8

- Marvianto, R.D., & Widhiarso, W. (2019). Adaptasi Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) versi Bahasa Indonesia [Adaptation of the Indonesian version of the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS)]. Gadjah Mada Journal of Psychology, 4(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamajop.45785 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22146/gamajop.45785

- Maulana, H. A., & Iswari, R. D. (2020). Analisis tingkat stres mahasiswa terhadap pembelajaran daring pada mata kuliah statistik bisnis di pendidikan vokasi [Analysis of student stress levels towards online learning in business statistics courses in vocational education]. Khazanah Pendidikan, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.30595/jkp.v14i1.8479 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30595/jkp.v14i1.8479

- Midi, H., Sarkar, S. K., & Rana, S. (2010). Collinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression model. Journal of Interdisciplinary Mathematics, 13(3), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720502.2010.10700699 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09720502.2010.10700699

- Mustafa, J., Zayed, N. M., Islam, M. S., & Islam, S. (2018). Students’ perception towards their teachers’ behaviour: A case study on the undergraduate students of Daffodil International University. International Journal of Development Research, 8(10), 23387–23392. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329040464

- Mutiara, T., & Rifameutia, T. (2021). Adaptasi alat ukur regulasi diri dalam belajar daring [Adaptation of self-regulation measurement tools in online learning]. Edcomtech: Jurnal Kajian Teknologi Pendidikan, 6(2), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.17977/um039v6i12021p301 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17977/um039v6i12021p301

- Myint, K. M., & Khaing, N. N. (2020). Factors influencing academic engagement of university students: A meta-analysis study. Journal of the Myanmar Academy of Arts and Science, 18(9B), 185–199. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352441444

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Nurfitri, Y. A., & Aslamawati, Y. (2021). Pengaruh self-regulated learning terhadap student engagement pada mahasiswa prodi teknik informatika [The influence of self-regulated learning on student engagement in informatics engineering students]. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 489–493. http://dx.doi.org/10.29313/.v0i0.28413

- Orr, A. M., & Kukner, J. M. (2015). Fostering a creativity mindset in content area pre-service teachers through their use of literacy strategies. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 16, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2015.02.003 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2015.02.003

- Owen, S. V, & Froman, R. D. (1988). Development of a college academic self-efficacy scale. Educational Resources Infoemation Center. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED298158

- Osborne, J. W., & Waters, E. (2002). Four assumptions of multiple regression that researchers should always test. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.7275/r222-hv23

- Pachler, D., Kuonath, A., & Frey, D. (2019). How transformational lecturers promote students’ engagement, creativity, and task performance: The mediating role of trust in lecturer and self-efficacy. Learning and Individual Differences, 69, 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.12.004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.12.004

- Palaniappan, A. K. (2009). Creative teaching and its assessment. Paper Presentation, 12th UNESCO-APEID International Conference with the Theme “Quality Innovations for Teaching and Learning”, Impact Exhibition and Convention Center, Bangkok, Thailand, March 24-26, 2009, 1–15. http://eprints.um.edu.my/541/

- Pramisjayanti, D., & Khoirunnisa, R. N. (2022). Hubungan antara self-efficacy dengan student engagement pada siswa SMP X kelas VIII selama masa pandemi COVID-19 [The relationship between self-efficacy and student engagement in class VIII students of X junior high school during the COVID-19 pandemic]. Character: Jurnal Penelitian Psikologi, 9(1). https://ejournal.unesa.ac.id/index.php/character/article/view/44709

- Primana, L. (2015). Pengaruh dukungan makna belajar dari dosen, motivasi intrinsik, self efficacy, dan pandangan otoritas sumber informasi terhadap keterlibatan belajar Mahasiswa Universitas Indonesia [The contribution of lecturer’s meaning support in learning, intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and student’s perceived epistemic authority, on learning engagement of Universitas Indonesia’s students] [Doctoral Dissertation, Universitas Indonesia]. https://lib.ui.ac.id/detail?id=20416085&lokasi=lokal

- Raviv, A., Bar-Tal, D., Raviv, A., Biran, B., & Sela, Z. (2003). Teachers’ epistemic authority: Perceptions of students and teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 6(1), 17–42. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021724727505 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021724727505

- Rodgers, T. (2008). Student engagement in the e-learning process and the impact on their grades. International Journal of Cyber Society and Education Pages, 1(2), 143–156. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/209167/

- Rusman, Abd. A., & Nasution, F. (2020). Deskripsi kebahagiaan belajar mahasiswa BKI pada masa pandemi COVID-19 [Description of BKI students’ learning happiness during the COVID-19 pandemic]. AL-IRSYAD, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.30829/al-irsyad.v10i1.7649 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30829/al-irsyad.v10i1.7649

- Sa’diyah, S. H. (2021). On off kamera dan implikasinya pada perkuliahan daring [Camera on off and its implications for online lectures]. Jurnal Pendidikan Indonesia (Japendi), 2(9), 1593–1603. https://doi.org/10.59141/japendi.v2i09.286 DOI: https://doi.org/10.36418/japendi.v2i9.286

- Sarjana, K., Hayati, L., & Wahidaturrahmi, W. (2020). Mathematical modelling and verbal abilities: How they determine students’ ability to solve mathematical word problems? Beta: Jurnal Tadris Matematika, 13(2), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.20414/betajtm.v13i2.390 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20414/betajtm.v13i2.390

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of psychological research online, 8(2), 23-74. https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~snijders/mpr_Schermelleh.pdf

- Setiani, S., & Wijaya, E. (2020). The relationship between self-regulated learning with student engagement in college students who have many roles. Proceedings of the 2nd Tarumanagara International Conference on the Applications of Social Sciences and Humanities (TICASH 2020), 307–312. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.201209.045 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.201209.045

- Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

- Soh, K. C. (2000). Indexing creativity fostering teacher behavior: A preliminary validation study. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 34(2), 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2000.tb01205.x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2000.tb01205.x

- Staikopoulos, A., OKeeffe, I., Yousuf, B., Conlan, O., Walsh, E., & Wade, V. (2015). Enhancing student engagement through personalized motivations. 2015 IEEE 15th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT.2015.116 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT.2015.116

- Suminta, R. R. (2016). Kecemasan statistik ditinjau dari dukungan akademik [Statistical anxiety and academic support]. Quality, 4(1), 120–139. http://dx.doi.org/10.21043/quality.v4i1.2117

- Ulpah, M. (2009). Belajar statistika: Mengapa dan bagaimana? [Leaning statistics: Why and how?]. INSANIA: Jurnal Pemikiran Alternatif Kependidikan, 14(3), 325–435. https://doi.org/10.24090/insania.v14i3.354 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24090/insania.v14i3.354

- Utami, R. D., & Aslamawati, Y. (2021). Pengaruh self-regulated learning terhadap student engagement pada mahasiswa prodi akuntansi di kota Bandung [The influence of self-regulated learning on student engagement in accounting students in Bandung]. Prosiding Psikologi, 7(2), 404–408. http://dx.doi.org/10.29313/.v0i0.28374 DOI: https://doi.org/10.29313/bcsps.v2i1.356

- Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164492052004025 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164492052004025

- van Petegem, K., Aelterman, A., Rosseel, Y., & Creemers, B. (2007). Student perception as moderator for student wellbeing. Social Indicators Research, 83(3), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9055-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9055-5

- Varatharaj, R. (2018). Assessment in the 21st century classroom: The need for teacher autonomy. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS), 2(6), 105–109. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ravikumar-Varatharaj/publication/326730856_Assessment_in_the_21st_century_classroom_The_nedd_for_teacher_autonomy/links/5b7ae65592851c1e1223a7e6/Assessment-in-the-21st-century-classroom-The-nedd-for-teacher-autonomy.pdf

- Waruwu, R. B., Hao, N. P., & Hia, P. H. (2022). Analisis kemampuan pemahaman mahasiswa pada mata kuliah statistika di STIKES Santa Elisabeth Medan tahun 2022 [Analysis of students’ understanding ability in statistics courses at STIKES Santa Elisabeth Medan in 2022]. SEHATMAS: Jurnal Ilmiah Kesehatan Masyarakat, 1(3), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.55123/sehatmas.v1i3.653 DOI: https://doi.org/10.55123/sehatmas.v1i3.653

- Warwick, J. (2008). Mathematical self-efficacy and student engagement in the mathematics classroom. MSOR Connections, 8(3), 31–37. https://web.archive.org/web/20170809041039id_/http://aces.shu.ac.uk/employability/resources/MSOR_8331_warwickj_mathselfefficacy.pdf DOI: https://doi.org/10.11120/msor.2008.08030031

- Watts, S., & Thomas, S. (2022, June 7). What is statistics in psychology? Study.Com. https://study.com/learn/lesson/statistical-methods-in-psychology-analysis-types-application.html

- Xia, Y., Hu, Y., Wu, C., Yang, L., & Lei, M. (2022). Challenges of online learning amid the COVID-19: College students’ perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1037311 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1037311

- Zaimil, R. (2017). Analisa kesalahan mahasiswa dalam mengerjakan soal pada perkuliahan Statistika 1 FKIP Ummy Solok [Analysis of student errors in working on questions in the Statistics 1 Course FKIP Ummy Solok]. THEOREMS (The Journal of Mathematics) , 2(1), 78–85. https://ojs.fkipummy.ac.id/index.php/theorems/article/view/124

- Zhang, Y., Li, P., Zhang, Z. S., Zhang, X., & Shi, J. (2022). The Relationships of Parental Responsiveness, Teaching Responsiveness, and Creativity: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748321 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748321

- Zhen, R., Liu, R.-D., Ding, Y., Wang, J., Liu, Y., & Xu, L. (2017). The mediating roles of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the relation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and learning engagement among Chinese adolescent students. Learning and Individual Differences, 54, 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.01.017 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.01.017

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_2

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909