From the history of ethnographic studies in the Yenisei region: F.A. Fjelstrup’s Siberian materials

Автор: Naumova O.B., Oktyabrskaya I.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article describes the works of Theodor (Fedor) Fjelstrup (1889–1933)—a Russian ethnographer, one of those who laid the groundwork for the systematic studies of the Turkic world of Central Asia. We used materials from the archives of the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology RAS (F.A. Fjelstrups' holding): the diary of the Minusinsk- Abakan 1920 Expedition and the notebook. We discuss the hitherto unknown episodes in the ethnographic studies of the Yenisei region, the foundation of the Institute for the Study of Siberia, the organization and work of the Minusinsk-Abakan 1920 Expedition, whose records we introduce, and its route. Data on settlements, utensils, clan structures, systems of kinship, family rites, folklore, and shamanic beliefs are analyzed. Using the historical approach, Fjelstrup traced the dynamism of the Khakas culture, being one of the fi rst to discuss the syncretism of their beliefs. Using materials of the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition, we demonstrate that he implemented a comprehensive approach combining linguistic, ethnographic, and anthropological evidence. This scholarly tradition, which was widely practiced in the 20th century, maintains its importance in future studies of the Turkic groups of Central Asia.

Institute for the study of siberia, minusinsk-abakan expedition, khakas traditional culture, f.a. fjelstrup’s archives, ethnography, the khakas people

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146878

IDR: 145146878 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.2.129-141

Текст научной статьи From the history of ethnographic studies in the Yenisei region: F.A. Fjelstrup’s Siberian materials

In recent decades, the Russian Humanities, which have been reassessing their approaches and values, manifest great interest in personalities and destinies of scholars who worked in the time of changing ideological doctrines and methodological concepts. Since the 1990s, many publications have been focusing on the persecuted ethnographers. Collected studies and monographs discuss outstanding scholars, such as Y.V. Bromlei, L.P. Potapov, G.M. Vasilevich, P.I. Kushner, N.P. Dyrenkova,

D.A. Klements, and others. An approach corresponding to the concept of new biographical history (“personal history”), focusing on personal information, followed in these studies. This approach emerged as a part of the “anthropological turn” and new understanding of man in history, and is distinguished by rejection of typification and by close attention to the context of personality formation. Working with author’s narrative has become an important task. Systematic study of personal archives has made it possible not only to clarify the facts of biographies, but also to identify socially important trends

that influenced the values of scholars and determined their scholarly endeavor.

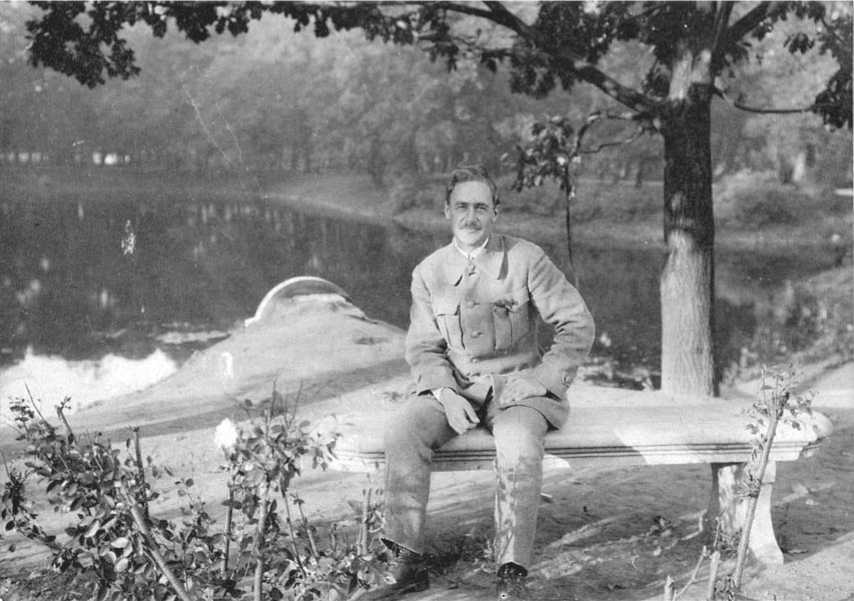

Growth of interest in the collections of documents belonging to Russian ethnographers of the early 20th century is associated with prospects for reconstructing “creative laboratories” of scholars who collected unique evidence, but did not implement their projects. These archives include the materials left by the Russian and Soviet scholar, ethnographer, and traveler Fedor A. Fjelstrup (1889–1933), whose name came back from oblivion only in the late 1980s (Fig. 1). His scholarly biography was reconstructed in the memorial edition “Persecuted Ethnographers” by the efforts of B.K. Karmysheva (2002).

It is known that Fjelstrup was born in St. Petersburg, in the family of a successful Danish engineer, who took the Russian citizenship. Fjelstrup graduated from St. Petersburg University, here he received a comprehensive education in the Humanities. As a student, he traveled to the Caucasus, Mongolia, and South America. For the report on the native Americans of Brazil, together with his colleagues, Fjelstrup was awarded the small silver medal of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. Since 1916, after graduating from the university, Fjelstrup was an employee of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (MAE)/Kunstkamera; since 1918, he collaborated with the Commission for Studying the Tribal Composition of the Population of Russia, compiling ethnic maps of the Cis-Urals. After that, Fjelstrup was invited to Tomsk University, where he taught a course in geography. In 1920, he became a member of the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition. Since 1921, being an employee of the Ethnography Department of the Russian Museum, he carried out ethnographic research in the Crimea, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. In 1933, Fjelstrup was persecuted and died during investigation; he was cleared of all charges in 1958 (Ibid.; Professora Tomskogo universiteta…, 2003).

During his lifetime, F.A. Fjelstrup published only several articles. In the early 2000s, all his manuscripts and field diaries were donated by his heirs to the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and formed collection No. 94, containing Fjelstrup’s field materials and studies of the 1920s. By the 2000s, the fragments of this archive on the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs were reviewed by B.K. Karmysheva, G.N. Simakov, and O.B. Naumova (Karmysheva, 1988; Simakov, 1998; Naumova, 2006a, b). Most of the field materials of Fjelstrup on the rituals of the life cycle among the Kyrgyz were edited and published by B.K. Karmysheva and S.S. Gubaeva in 2002 (Gubaeva, Karmysheva, 2002; Fjelstrup, 2002). All other materials, including the results of the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition of 1920, have never been discussed. The information collected during this expedition appears in the diary (D) and notebook (NB) of Fjelstrup. His field materials (FM) were supplemented with

Fig. 1 . F.A. Fjelstrup. Photo of the 1920s. Archive of IEA RAS. F. No. 94.

extracts from publications and descriptions of museum exhibits. This article intends to describe and discuss this evidence.

This article analyzes the Siberian part of the Fjelstrup’s archive, which is about 400 pages of text, and interprets it in the context of his research, taking into account systemic transformations that took place in Siberia in the early 20th century.

Background of the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition

The Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition of 1920, in which Fjelstrup was a member, was organized by the Institute for the Study of Siberia together with Tomsk University. In compiling the plan for the journey, its organizers relied on available experience of studying Siberian regions.

By the early 20th century, the valley of the Middle Yenisei River was one of the best studied areas in Russia. The first sensational discoveries there were associated with activities of illegal grave robbers in the early 18th century. The “Golden Siberian grave things” became known in the capital city in 1715, when the Siberian Governor General Prince M.P. Gagarin brought several items to Peter I. In 1718, Peter I signed a decree on the Siberian Expedition under the leadership of Dr. D.G. Messerschmidt, who was invited to Russia. In 1720–1726, Messerschmidt traveled from the Urals to Lake Baikal and from the Sayan to the Lower Ob region. Part of his route passed along the Yenisei lands, which in 1707 became a part of Russia. The objectives of the expedition included studying “pagan idols”, “ancient writings,” “stone statues,” etc. Messerschmidt excavated burial mounds on the left bank of the Abakan River, sketched rock art on the Yenisei River, and was the first scholar to describe the ritual of worshipping the stone statue of Ulug Khurtuyakh Tas (Kyzlasov, 1983). Scholarly expeditions in the region were carried out during the 18th–19th centuries. In 1893, the Danish linguist V.L. Thomsen read the inscriptions on the Uybat monument—the stone stele discovered by Messerschmidt. The decryption of runic script as the Orkhon-Yenisei ancient Turkic script, as well as discovery of sites from different periods, opened up the discussion on the emergence of cultures in the region (Ibid.).

The study of the Yenisei region at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries was associated with the names of famous scholars, such as F.Y. Kon, D.A. Klements, A.V. Adrianov, N.F. Katanov, S.D. Mainagashev, and others. The Minusinsk Museum, founded in 1877, acquired the status and reputation of one of the leading research centers of Siberia (Kon, 2019). In 1900, vast ethnographic collections of the museum were presented in a catalog prepared by E.K. Yakovlev (1900).

Researchers from Kazan University, where a school of comparative historical study of languages and cultures of the Turkic peoples had emerged by the early 20th century, had a noticeable influence on research in the Altai-Sayan region. V.V. Radlov, Professor of Kazan University in the 1870s, became one of the leading scholars in that field. He was a versatile and outstanding Turkologist, well-versed in linguistics, ethnography, and archaeology of Siberia and Central Asia, and supported research in the Altai-Sayan region already in the rank of Academician and Director of the MAE/Kunstkamera (Kononov, 1972).

The work of N.F. Katanov—one of the most famous linguists of Russia and representative of the indigenous population of the Yenisei region—was also associated with Kazan University. After graduating from St. Petersburg University in 1889–1892, he focused on studying the Turkic world. In 1919, he was elected Full Professor. One of his students was S.E. Malov—a native of Kazan, graduate of the local Theological Academy, and subsequently of St. Petersburg University. Still during the years of his studies, with the support of Radlov, Malov traveled to the south of Siberia. During the trip, he became interested in ancient runic script, language, and views of the indigenous inhabitants of the region. In 1917, Malov became a professor at Kazan University (Kormushin, Nasilov, 1978).

In this center of research, much attention was paid to the theory of the Altai linguistic unity and Altai-Sayan (Central Asian) ancestral homeland of the Finno-Ugric peoples. This theory was proposed in the mid-19th century by the Finnish scholar M.A. Castrén, but was later refuted. However, in the early 20th century, linguists, archaeologists, and ethnographers actively participated in the discussion about this theory. Minusinsk and Achinsk uyezds (previously, okrugs) of the Yenisei Governorate were the regions where such studies were carried out. In 1912–1913, S.A. Teploukhov—at the time, a junior representative of one of the dynasties of entrepreneurs and scholars in the Urals—worked there. He was a graduate of Kazan University, and had additional training at St. Petersburg University, focusing on anthropology and archaeology. In 1918, being in the Urals, which at that time was under the rule of Kolchak, Teploukhov was sent to Tomsk, together with other professors of Perm University. Some employees of Kazan University were also transferred there (Kitova, 2010).

Working prospects for the scholars who ended up in Tomsk were associated with the foundation of the Institute for the Study of Siberia. The Institute was intended to serve as All-Siberian Center, which would foster the study of the region. The Department of History and Ethnology, which was expected to “study history (including archaeology), everyday life, disposition, language, literature, beliefs, and art of the peoples of

Siberia (Russian, foreign, and indigenous population), and protect all kinds of antiquities and documents of the past and present” (Trudy syezda…, 1919: 33), became a part of the Institute. The Institute was created during the establishment of the Soviet power in 1917–1918, but acquired the status of a state institution after receiving support of the Kolchak’s regime, which was established by the fall of 1918 and overthrown in December 1919. In 1919, the Institute was headed by V.V. Sapozhnikov, Professor of Tomsk University; Department of History and Ethnography was headed by S.I. Rudenko (Nekrylov et al., 2012; Molodin, 2015).

A graduate of St. Petersburg University, S.I. Rudenko had a reputation of one of the most effective Russian scholars focused on systemic archaeological, ethnographic, and anthropological studies. Since the early 1900s, he worked in the Ukraine and Western Siberia; in 1915, he became an Assistant at the Department of Geography and Anthropology of Petrograd University; in 1916, he published the book “The Bashkirs: Experience of Ethnographic Monograph”, and was appointed Academic Secretary of the Commission for Studying the Tribal Composition of the Population of Russia and Adjacent Countries. In 1919–1921, Rudenko worked at Tomsk University as a Privat-Docent, then Professor and Head of the Department of Physics and Mathematics. He combined teaching with working in the Institute for the Study of Siberia; at the same time, he headed the museum at the Department of History and Ethnography of the Institute and Commission on compiling maps of peoples (tribes) of the region (Kiryushin, Tishkin, Shmidt, 2004).

In the scope of the Commission’s work, Yenisei region was of great interest for scholars and practitioners. There, in April 1918, the Minusinsk Council of Workers’, Peasants’, Soldiers’, and Cossacks’ Deputies recognized the rights of the indigenous population and approved its single self-name as “Khakas”. Thus, the historical ethnic name related to the state of medieval Kyrgyz people was returned from the oblivion. The establishment of the name “Khakas” leveled the exoethnic names of the Minusinsk, Kuznetsk, and Achinsk Tatars, and marked the process of consolidation of clan-related and tribal associations of the Sagai, Beltir, Kacha, Koybal, and Kyzyl, who emerged in the Kacha, Koybal, Kyzyl, and Sagai indigenous administrations. This actualized the study of ethnic history of selfregulated Khakas people, their linguistic and cultural unity, and ethnolocal differences (Efremova, 1972). Addressing ethnic and historical issues involved reliance on comparative linguistic, archaeological, ethnographic, and anthropological studies, which were planned as a part of the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition. This was the first integrated expedition in Siberia, still experiencing the consequences of the Civil War. Its strategy was determined by the concept of one of the leaders of the Russian ethnography of D.N. Anuchin, who advocated the trinity of sciences—ethnography, archaeology, and anthropology (Levin, 1947).

Organization and work of the expedition

The Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition of 1920 was headed by S.I. Rudenko; F.A. Fjelstrup was one of its members. He came to Tomsk on recommendation of Rudenko, whom he knew from St. Petersburg University. Together they mapped settlement places of the peoples of the Urals in 1918. In Tomsk, Fjelstrup served as a Junior Assistant at the Department of History and Ethnography of the Institute for the Study of Siberia, and worked as interpreter in the government of Kolchak.

In the summer of 1920, Fjelstrup joined the integrated expedition, which included the following members: S.A. Teploukhov, at that time a Senior Assistant at the Department of Geography and Anthropology of Tomsk University, I.M. Zalessky—ornithologist and artist, A.K. Ivanov—geographer, Junior Assistant (later, Associate Professor) at the Department of Physics and Mathematics of Tomsk University and his wife K.P. Kuzmina—a doctor. The team had three students, including M.P. Gryaznov—a student at the Division of Natural Sciences of the Department of Physics and Mathematics, and later one of the leading Russian archaeologists of Siberia (Rudkovskaya, 2004; Kitova, 2010; Berezovikov, 2017). A group of mineralogists in the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition (professors and students) worked under the supervision of S.M. Kurbatov, Professor of the Department of Mineralogy and Geology of Tomsk University. When leaving Tomsk, the team of 11 people with equipment (and two wagons) occupied two heated freight cars (Archive of the IEA RAS, F. 94, D, fol. 1).

According to the Fjelstrup’s notes, the expedition lasted from June 1 to September 27, 1920. The first pages of his diary were filled with descriptions of the blooming steppe. During the field work, there were rains, hurricane winds, and a sandstorm. Snow fell during the last days of the expedition.

After leaving Tomsk, the expedition reached Achinsk, then traveled on horseback through the villages of Andropovo, Uzhur, and Kopyevo, reaching Lake Shira. The situation with the population in uluses and villages along the route of the expedition was often disastrous. By the summer of 1918, the Soviet power had been overthrown in Siberia. The civil war continued in 1918– 1919. By the beginning of 1920, Siberia was almost completely liberated from the Kolchak troops. The Soviet power was restored in the Minusinsk region, but there were still “gangs of rebels against the authorities”, who were engaged in plundering. The region was flooded with military units. In his diary, Fjelstrup wrote: “We ended up in inconvenient time for driving along the highroad; an entire army division is returning from the Minusinsk region. Columns of black dust rush along the road; villages feed everything clean to hungry soldiers; housing is taken by the military units; all carts are busy on assignments. There is no oats and hay; horses are fed with straw…, with great difficulty I got a horse in a cart in the ulus; all carts were taken by the Reds, and other carts were mobilized to transport coal to Ust-Abakan…; boats were taken by the Whites, and the rest were destroyed by the Reds” (Ibid.: fols. 7, 73–74).

Research works were carried out in a very difficult situation. Yet, despite all difficulties, thanks to human and professional qualities, as well as experience in the field, Fjelstrup and his colleagues managed to accomplish a large amount of archaeological and anthropological research, and capture the life of the Khakas people in first post-Revolution years in all its diversity.

The program of ethnographic research was outlined by Fjelstrup on the first pages of his notebook (Fig. 2). It included the following sections: social system, knowledge about man and nature, cosmogonic and astronomical concepts, description of shamanism, etc. He also mentioned the topics studied by S.I. Rudenko (cattle breeding, clothing, leather and bone processing, art, childbirth, burials) and I.M. Zalessky (hunting and fishing). Teploukhov collected information on economic activities, food, housing, games, etc. (Ibid.: NB, fols. 1r–1v).

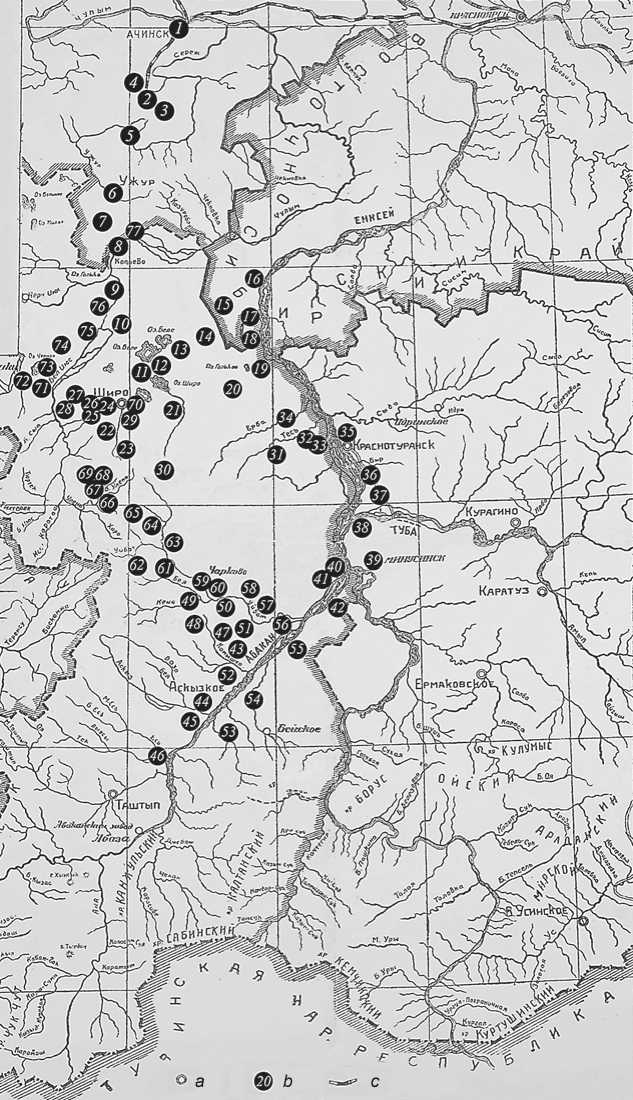

Throughout June, Fjelstrup and his guides traveled around the uluses of Bolshiye Vorota, Dzheroma, Marchilgas, Malyi Kobezhekov, and Efremkin, the villages of Tyun, Chernov, and others, where he collected rich linguistic, folklore, and ethnographic evidence. Near Efremkin ulus, the members of the expedition examined several caves. Since the beginning of July, near the village of Buzunovo (the former Cossack village) and the ulus of Asochakov (Achanai), excavations of burial mounds were carried out under direction of Rudenko (Fig. 3).

From Asochakov ulus, Rudenko and Fjelstrup went to the headwaters of the Askiz River, and further up the Kamyshta River. In August, the season of sacrifices and weddings began. Scholars attended traditional rituals and collected evidence about shamans, singers, and storytellers in the uluses of Asochakov, Charkov, Tazmin, Ulen, and others. One of their interpreters and guides on the travels along the Beya River was F.Y. Saradzhakov. At the end, he went with the expedition to Tomsk to do the eye surgery (Ibid.: D, fols. 73, 74v.).

As a part of the 1920 expedition program, Teploukhov studied collections in Krasnoyarsk and Minusinsk museums; a microdistrict for systematic excavations was chosen near the village of Baten, on the left bank of the Yenisei River. Since the beginning of September, the expedition members carried out archaeological research in the uluses of Aeshino and Kopyevo, where six burial mounds were excavated.

Historiographers believe that four cemeteries of the Tagar culture, with the total of 15 burial mounds, were excavated under the leadership of Rudenko during the

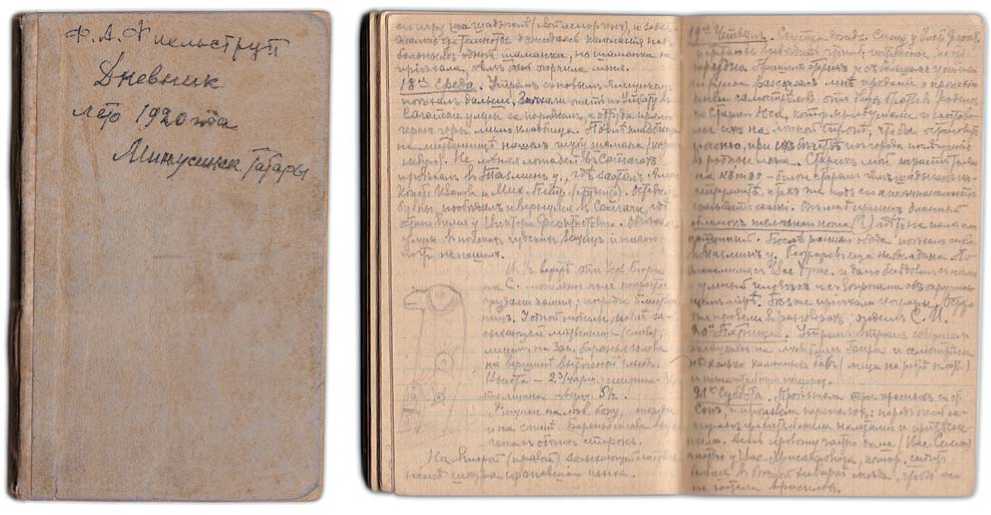

Fig. 2 . Cover and pages of the Fjelstrup’s diary. Minusinsk-Abakan expedition of 1920. Archive of IEA RAS. F. No. 94.

Fig. 3 . Area of work of the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition of 1920. This layout was compiled using the map of Khakassia of the late 1920s–early 1930s by O.A.

Mitko.

1 – Achinsk; 2 – Glyaden; 3 – Stepnaya; 4 – Antropovo; 5 – Maryasovo; 6 – Uzhur; 7 – Uchumskaya ekonomiya; 8 – Kopyevo; 9 – Syutik; 10 – Solenoozerskaya (Solyanoi Forpost); 11 – health resort on Lake Shira;

12 – Kolodets; 13 – Bolshiye Vorota; 14 – Idzhim; 15 – Tyup; 16 – Ayoshki; 17 – Chernovo; 18 – Saragash; 19 – Ekonomiya Chetverikova; 20 – Beibulak; 21 – Alekseevskiy Rudnik; 22 – Oroshtaevskiy; 23 – Verkhniy Tuim; 24 – Marchelgash;

25 – Malyi Kobezhekov; 26 – Topanov; 27 – Aeshin; 28 – Efremkin; 29 – Malyi Spirin;

30 – Son; 31 – Potekhino (Bolshaya Erba);

32 – Sukhaya Tes; 33 – Abakano-Perevoz; 34 – Znamenka; 35 – Abakanskoye; 36 – Buzunovo; 37 – Listvyagovo; 38 – Gorodok; 39 – Minusinsk; 40 – Ust-Abakanskoye; 41 – Sapogovskiye Ulusy; 42 – Beloyarskiy; 43 – Ust-Kamyshta; 44 – Askiz; 45 – Asochakov (Achanai); 46 – Ust-Es; 47 – Epishekov; 48 – Sinyavino; 49 – Kolpakov; 50 – Pokoyanov;

51 – Balaganov; 52 – Sarazhakov; 53 – Uty; 54 – Aidolovskiy; 55 – Arshanov; 56 – Kalagashev; 57 – Kapchaly; 58 – Verkhneye Kobelkovo; 59 – Charkov; 60 – Nizhniy Charkov; 61 – Tokamesov; 62 – Maganak; 63 – Ust-Byur; 64 – Sagaichi; 65 – Tazmin;

66 – Bolshoi Ulen; 67 – Malyi Ulen; 68 – Ultugash; 69 – Sichentash; 70 – Kamyshev; 71 – Tarcha; 72 – Chebaki; 73 – Chernoye Ozero; 74 – Zaplot; 75 – Bolshoi Klyuchikov;

76 – Kozhakov; 77 – Torchuzhany.

a – settlements on the basic map; b – settlements on the route of the expedition, identified by O.A. Mitko; c – railway.

Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition (Rudkovskaya, 2004). At the end of the expedition, the Department of Geography at Tomsk University received eight archaeological collections and anthropological remains—evidence from the excavations. Fjelstrup was in charge of assembling ethnographic collections during the expedition. In Bolshoy Ulen ulus, he acquired a cradle frame, mill, deer pipe, and other things; in Malyi Ulen he procured a copper dagger; in Ulgutas mittens and cradle, etc. At the end of September, the team shipped the equipment and exhibits, and set off on the return journey from Achinsk to Tomsk (Ibid.).

Field materials of F.A. Fjelstrup

Records of Fjelstrup made during the expedition of 1920 were divided into several sections. For the field studies, he elaborated a sophisticated system for the recording of sounds, using the Latin and Cyrillic scripts, following the methods of his teachers and colleagues, linguists S.E. Malov and S.A. Samoilovich. Fjelstrup recorded his informants “from the voice”, capturing both dialect-related and individual features, which made it possible to convey the “actual fluid nature and character of the language” (Malov, Fjelstrup, 1928: 291).

Linguistic evidence included names of seasons of the year, months, time of day, etc.; astronomical, geographical, and meteorological vocabulary; names of body parts, plants, wild and domestic animals, fish, birds, insects, parts of the dwelling, as well as musical instruments and feasts.

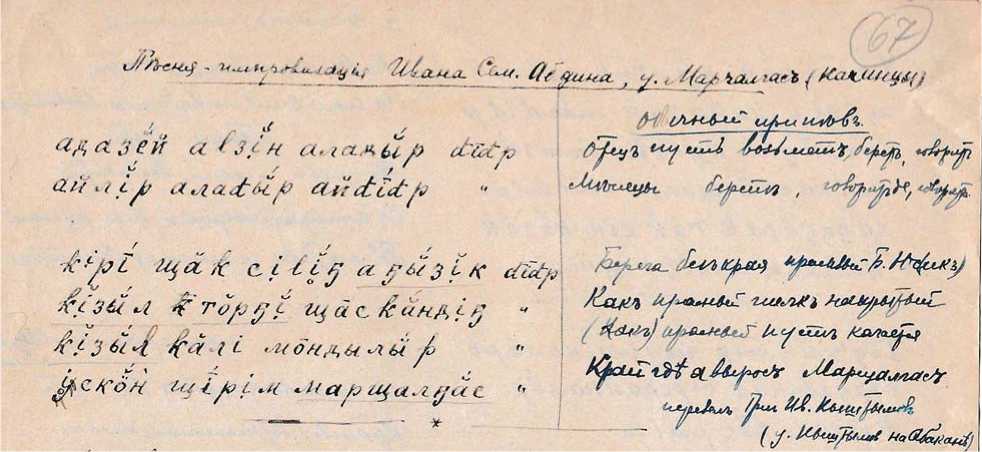

Starting with the Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition, Fjelstrup paid great attention to collecting terms. He was one of the first scholars who appreciated the importance of their recording for recreating the dynamic image of culture (“archaeology of culture”), attached exceptional importance to etymology, which not only revealed the nature of things and phenomena, but also fostered building ethnogenetic models, which was particularly interesting for the scholar. He made records among all groups of the Khakas people—the Kacha, Sagai, Beltir, and Kyzyl—which made it possible to conduct further comparative and linguistic studies. In his diary, Fjelstrup described the linguistic situation in the region as a whole. For example, working in Marchelgash ulus, he wrote: “My interlocutors speak Russian rather well… The acclimatization of the Russian language among the local Kacha people quickly advances: they constantly insert Russian words into their speech and replace their own words with Russian words. In several cases, I noticed the loss of consciousness that this word was of Russian origin (for example, taz , kolechko , etc.) among young people… The assimilated Russian words are, of course, subordinated to the grammatical system of the Tatar language” (Ibid.: D, fol. 57).

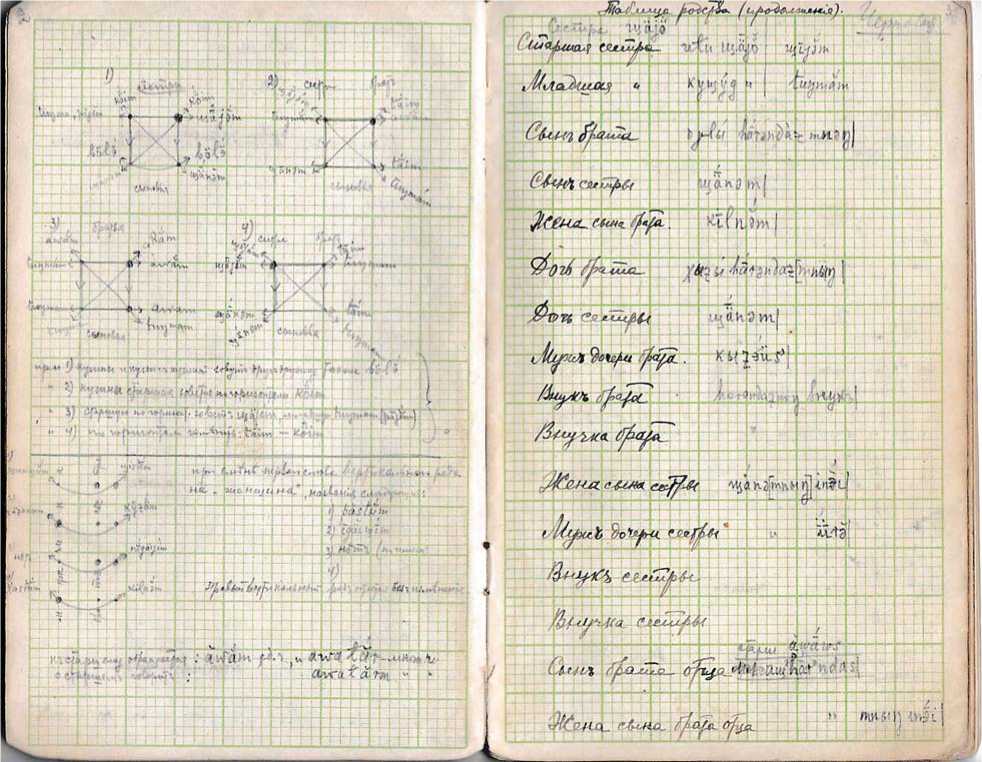

Another significant section of evidence included the terms of kinship, names of sӧӧks (patrilinear exogamous units), as well as information about tamgas and their images. After conversations with informants, Fjelstrup compiled kinship tables. He probably wanted to prepare a summarizing publication on the system of clan structures and relations of the Turkic world, since his manuscripts contained extracts from rare studies of the early 20th century on the Kacha and Beltir people, Chuvashes, Kazan Tatars, Bashkirs, Kazakhs, and Tuvans (Ibid.: FM, fols. 43, 44, 60–61) (Fig. 4).

The Fjelstrup’s manuscripts contain records on family rites and customs of avoidance; rituals associated with hearth, setting up the yurt, etc. They include extensive information about settlements, dwellings, household items and utensils of the Khakas people, as well as descriptions of musical instruments, techniques of playing them, and restrictions regarding the performance of music.

Information on the traditional worldview of the Khakas people, represented by shamanic rituals that he attended, very widely appears in the Fjelstrup’s holding. In his field studies, the scholar used the already known publications of A.V. Adrianov, D.A. Klements, N.F. Katanov, S.E. Malov, and others (Klements, 1892; Katanov, 1897; Adrianov, 1909; Malov, 1909; and others).

In Efremkin ulus, Fjelstrup recorded a story of the local resident P.F. Kishcheev about the masters of mountains. The old man complained that “people do not believe in God, do not like shamans, do not believe that there are masters of forest, mountains, and water”; people had not been offering sacrifices to the sky for ten years, from which misfortunes came (Ibid.: D, fols. 61–66).

The Khakas people believed that masters of mountains loved fairytales, and in order to win their favor they took fairytale-tellers with them to the hunt. This is reflected in the story told by P.F. Kishcheev: “Once, when he was young, people from different uluses came to a mountain to gather lingonberries; at some distance, they made fires. People were reckless; they laughed, made noise; some were telling fairytales, but many were not listening. But the master often listens to fairytales; if he likes a fairytale and people attentively listen to it, he leaves satisfied, laughs, whistles; he can be heard when he walks—he paces heavily. Thus, he began to bark like a small dog with a thin voice behind the mountain, then whistle sharply, so the ear hurt. And in the morning, two men went crazy, and they had to be tied and taken home. You can rarely see the master. Once Pavel listened to a fairytale somewhere by the fire… When the fairytale was over, the master apparently liked it and left satisfied; it was heard how he was knocking and walking, passing by them. Usually, only a shaman can see the master” (Ibid.: Fols. 62–63). According to P.F. Kishcheev, the mountain people live like ordinary people—they get married and have children; sometimes, they appear among the living. “Masters are not all in one place, but they come every now and then. Sometimes, he even comes to the ulus, enters, drinks a little of wine, and then, as he goes out the door, he puts on the skis and quickly leaves like the wind. They have a house somewhere. There was one hunter (his grandson still lives in Kabezhikova), …he was in the forest, staying there. A girl arrived and asked him to come to help— a woman was trying to give birth the third day, but was not able to—he did not believe, did not go. Then again, already two, this girl and husband of the woman in labor; they were really asking and promising to reward him whatever he wished, just let him help. They looked, as he said, like all people, only was there no hair on the eyebrows. Well, he went, arrived at a rock where the

Fig. 4 . Pages of the Fjelstrup’s notebook, with information on the Khakas kinship system. Archive of IEA RAS. F. No. 94.

entrance was just a crack. They opened it, let him in, one in front, the other behind. Inside, everything was like in a real house, and everything in the world was there. A woman lay there too. He did not know how to help… So, he pressed somewhere, and the woman gave birth, to a boy, I think. Then they said: ‘Take whatever you want as a reward’. They led him to the next room (it was light everywhere, as it should be). There was everything whatever one may wish. Gold, silver, furs… But they could not give him anything, because he did not want to take. Some blood got on his clothes. ‘Then, they say, here is a reward for you—you will be a great shooter until old age, and you will feed on hunting all your life; you will never starve; you will always find the animal and kill it’… And indeed, he was a great shooter. He was a hundred years old when he killed the last bear. … That’s the story, I know myself, but people don’t believe that there is God and the masters!” (Ibid.: Fols. 64–66).

Contrary to skepticism of the informant, according to the Fjelstrup’s observations, the Khakas people regularly revered mountains and their masters. In the Askiz area, the expedition members saw an altar yzykh-taikh; near Epizhekov ulus, they observed the sacrifice to the “stone woman” (transported to the Minusinsk Museum); in August, the team was planning to attend four local taikhs.

Evidence on shamanism occupies a large part of the Fjelstrup’s records. He described the rituals of the Sagai shamans, including the “foot shaman”, who did not have a tambourine, perceived as a riding animal. The Khakas people called the shamans who had the outfit and tambourine “horsemen”. Despite the fact that the sacred attributes were the taboo in the traditional culture of Khakas people, Fjelstrup, according to his own words, easily found tambourines and clothing of the deceased shamans, using the help of his guides (Ibid.: Fols. 73v, 76v–77v).

On the pages of his notebook, Fjelstrup described in detail the healing session of a child by a Sagai female shaman. The rite lasted all night, and was preceded by long preparations. After fortunetelling on a cup, the shaman found out what things she needed. For performing the rite, a lasso was stretched on the left of the door, on which nine clothes turned inside out were hung. These were intended for the spirits that inflicted the disease. Two birch branches used for cleansing were placed nearby. A ram was slaughtered; its head, heart, and liver, right shoulder blade, and ribs were boiled. Next to the clothes, the shaman put a table covered with a ram skin, then poured araka in nine bottles, and set them there. She laid out the cooked meat into three wooden troughs, and put two of them on the table. For sprinkling (“sökenye”), wild thyme grass was brewed, and milk was boiled. Before the session, the fur coat and tambourine were sprinkled with araka. The owner of the yurt (the husband of the shaman) walked around the yurt and thurified everything with wild thyme. First, the shaman treated the child with “spells and sweeping with the old lopot”, that is worn clothes.

Fjelstrup observed the rite and noted that its participants were not allowed to sleep; otherwise, it would be difficult for the shaman to perform the ritual; people staring also disturbed her. At times, those who were present helped the shaman by repeating her exclamations over the patient. Those who entered the yurt later were also fumigated with wild thyme. Describing the rite, Fjelstrup paid attention to the local features: “The Kacha shamans perform rituals only at night, while the Sagai shamans at any time” (Ibid.: FM, fols. 1, 4v).

In 1920, Fjelstrup described four shamanic tambourines in detail. One of them, according to the instructions received by shaman in a dream, was covered by drawings: “8 red helpers and 1 senior helper with a bow, 1 rider with an extra horse; a frog, a snake, and a dog – with red paint, and a white birch on the right – below”. At the top, there were images of “a red sun, a white crescent moon, 2 red eagles, 2 white eagle owls, a red fir tree, and a white izykh”. The scholar described the clothes and headwear of the shaman, and found out that he was made to perform the ritual by “black people”— helpers of his predecessor; they also “gave him words” (Ibid.: NB, fols. 100–101; FM, fols. 1– 2v).

According to the Fjelstrup’s informants, “black people” also sent the diseases to a person by the wind. It is known that the element of the wind, according to the Khakas people, was associated with spirits; black color served as a distinctive feature of the underworld (Burnakov, 2008: 614).

“Black people” were mentioned in the Fjelstrup’s records about the fortuneteller on a shoulder blade: “They [the so-called black people – the Authors ] led him into the hut, where white (not burnt) and black (burnt) ram shoulder blades hang on the walls on the right and left, and told him to make a fortunetelling. He refused to tell fortunes on white shoulder blades, because they were dazzlingly bright and he could not look at them. Two patients lay in front of him: one was ill for a long time, and the other became ill very recently. He began to tell fortunes on the burnt shoulder blades and saw that the person who was sick for a long time was destined to recover, while the other person was destined to die. ‘Black people’ taught him the incantations and methods of fortune telling. The shaman whom he asked for interpretation of the dream told him that he should become a fortuneteller” (Ibid.: FM, fol. 3) (Fig. 5).

The story of the transformation of shamans into eagle owls was recorded by Fjelstrup from the Kacha people: “Sometimes, late travelers meet an eagle owl on the road. If this eagle owl is a shape-shifting shaman, then, seeing a

Fig. 5 . Pages of the Fjelstrup’s field records with folklore records. Archive of IEA RAS. F. No. 94.

man, he will shake and make sounds similar to tambourine clinking. To prevent harm, the traveler throws him cereals or something from his supplies. If one shoots such an eagle owl, the shaman performing the ritual at that same time would immediately die” (Ibid.: Fol. 1).

Judging by numerous extracts from literature and museum inventories, Fjelstrup thoroughly studied the topic of tӧses —anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images of family and clan patrons and helpers of shamans. He himself also described several of such images. One of them—“tileg tӧs” (the patron of livestock, keeper of ayran and dairy products)—he saw among the Sagai people: “tilég-tӧs is a short wooden fork on a very long stem. The ends of the fork are connected across by a band made of goat skin. From this band, the following ends are hanging: small blue and larger green scraps, and fringe in almost a quarter made of woolen yarn twisted in two threads of gray and brown wool”; it is kept on the female half of the house, behind the dishes. Fjelstrup also recorded: “altynnik-tӧs” (altyn tӧs) – the golden tӧs , and two “aba tӧs” – bear tӧses . Each of them looked like “a piece of skin from the head of a bay horse, with tendon” and was stored in the corner, to the left of the door (Ibid.: Fols. 5v, 7).

Noteworthy are two tӧses that Fjelstrup called “ōdinӓzy”. One of them was “a rectangle of canvas measuring ca 4 × 6 vershoks, with traces of red lines from the drawing… splattered with sacrifices. A red scrap was tied to the left corner, and a strand of combed tendons was next to it. In the middle, three pieces of otter skin were sewn in a row, at some distance from each other”. The other tӧs had a drawing, which did not survive on the first one: “red drawing on white canvas: three people stand in a row, with a tree having its roots up and a tree having its roots down on the right and left sides from them; above the trees, there are the crescent moon and the sun; the drawing is framed by a zigzag. A wooden ring, implying shaman’s tambourine, is sewn to the sun; under it, there is a strand of combed tendon (not a sheep’s). A scrap of red fabric is tied to the right corner of the canvas. Otter skins are between the sun and the moon” (Ibid.: Fol. 5v). Judging by modern research, this was chalbakh tӧs— one of the most revered tӧses among the Khakas people (Burnakov, 2020: 48).

Three of the tӧses described by Fjelstrup (“korshӓ”, “kinen,” and “kuryon-yzykh”) were tied to yzykhs— sacred horses that, according to the beliefs of the Khakas people, served as riding animals for the spirits (Burnakov, 2010). Korshӓ was an autumn squirrel skin, a gray yzykh horse was dedicated to it; kinen was in the form of sable skin, a chestnut yzykh was dedicated to it (Ibid.: Fol. 7). Kinen tӧs is well known to modern scholars (Butanaev, 1986: 89–107; Burnakov, 2020: 93– 96). Korshӓ tӧs (in the description of Fjelstrup) could have been khorcha tӧs—the celestial fetish, patron of gray horse-yzykh, according to V.Y. Butanaev. However, according to the description made in the 1990s, it was very different from that given by Fjelstrup. Butanaev supposed that khorcha tӧs was a birch fork with a “face” from a scrap of golden brocade, with “eyes” made of blue beads, and grouse wings (1999: 191).

Kuryon-yzykh as a tӧs has not been described in the literature. Its name comes from the word “kӱren” (‘brown/dark reddish’), because the yzykh of brown color was dedicated to it. Kuryon-izyk, according to Fjelstrup, was “the old shirt of the owner, to which a red scrap was sewn on the right side, 2 pieces of otter skin, a gold thread, a strand of tendon, and an iron wedding ring covered with sheet copper (substituting the tambourine?)” (Ibid.: Fol. 7).

While recording information about tӧses and yzykhs , Fjelstrup paid attention to the related rites: “Izykh is kept for 9 years (3 × 3)*. On the third taik (in the 9th year), new tӧses are brought, together with candidate-colts”; old tӧses are not let down on the river on the raft, but “people take them to the taiga and hung them on the birch, tying them tightly so they don’t fall down. …If izykh dies, people tear off the skin from it (and take it for themselves), and hang the head and legs on the birch. The new izykh is then washed at home, without shaman; old tӧses remain until the expiration of their term. While washing the izykh, special dishes are used”; izykh “cannot be harnessed, and a woman should not come close to it; only the owner can use it and only for riding. Izykh at the taik is tied to a birch…, in the case of change, along with the candidate. After the taik, after washing a new izykh… they release it into the wild. People also keep izykhs at home. These are dedicated during going to pastures in the spring, are sprinkled with araka, washed with milk, and released into the wild” (Ibid.: Fols. 6r–6v).

When describing the location of tӧses in the yurt, Fjelstrup always mentioned their position in relation to the “icon wall”; he also noted that the Khakas people “while entering the yurt, always make the sign of the cross (even when they are completely drunk), and then make a greeting” (Ibid.: D, fol. 54). It is known that by the early 20th century, most of the Khakas people were baptized in Orthodoxy, which probably had a “ritualistic” nature. In Asochakov ulus, Fjelstrup was shown a gold-laced caftan sent from the Imperial Court to clan chief Apak for the baptism of three thousand of indigenous persons on one day in 1877, as evidenced by the corresponding letter** (Ibid.: Fol. 75).

Observing and describing everyday and ritual practices of the Khakas people, Fjelstrup mentioned the phenomenon of dual faith, although he did not investigate it on purpose. For example, in one of localities on the Tuim River, he saw a larch that was charred at the base from bonfires; a pelvic bone of an animal (evidence of sacrifice) hung on the branches of the tree; and a large Orthodox cross was carved on the trunk (Ibid.: Fol. 51). Many decades later, this syncretism of the beliefs and rituals of the Khakas became the subject of research by ethnologists and religion scholars.

Conclusions

F.A. Fjelstrup intended to continue the systematic study of beliefs and culture of the Khakas people, initiated by the Minusinsk-Abakan 1920 Expedition, next year, but the situation changed. When the Soviet power in Siberia returned, the work of the Institute for the Study of Siberia was aborted, and it was closed on July 1, 1920 by the order of the Siberian Revolutionary Committee (Zhurnaly zasedaniy…, 2008). The persecution of university professors who collaborated with the Kolchak government began. In 1921, Fjelstrup returned to Petrograd together with Rudenko and Teploukhov. Their further work was associated with the Russian Museum, Academy of the History of Material Culture, and Petrograd University. Gryaznov (a student of Teploukhov) transferred to Petrograd University (Karmysheva, 2002; Pshenichnaya, Bokovenko, 2002: 20; Kiryushin, Tishkin, Shmidt, 2004).

Although the ethnographic studies initiated in 1920 were discontinued, the findings of the integrated Minusinsk-Abakan Expedition were of great importance. The observations of Rudenko and Fjelstrup—members of the Commission for Studying the Tribal Composition of the Population of Russia—were apparently taken into consideration during ethnic-territorial zonation of the Yenisei region. In 1923, the Khakas Ethnic Uyezd, which later became okrug and then autonomous region, was created in the area where the community accepting the name of “Khakas people” lived (Efremova, 1972).

The results of the expedition were used by its participants in preparing summarizing publications. Using the evidence collected, Teploukhov developed the chronology of archaeological cultures of the Khakas-Minusinsk Basin, which corresponded to evolutionary-paleoethnological concepts followed by the author and his colleagues. In line with the same concepts, Fjelstrup wrote articles describing wedding dwellings and dairy products; he published folklore texts in collaboration with Malov (Kitova, 2010; Fjelstrup, 1926, 1930; Malov, Fjelstrup, 1928).

The research carried out by Fjelstrup was aimed at identifying ethnogenetic, historical, and cultural patterns in the development of the Turkic peoples of Siberia and Central Asia. Since 1921, being an employee of the Russian Museum, he Fjelstrup has made a number of expeditions to Central Asia and Kazakhstan (Karmysheva, 1988). He analyzed new field evidence focusing on comparative analysis of cultures and languages of the Khakas people, Kyrgyz people, Kazakhs, Crimean Tatars, and Nogais, which resulted in some prospects of further studies of the Turkic population living in Central Asia. Unfortunately, these plans were not destined to be fulfilled, since repressions began in the country. In 1930, Rudenko, in 1933, Gryaznov, Teploukhov, Fjelstrup, and others were arrested on false charges. After exile and forced labor camps, Rudenko and Gryaznov returned to scholarly work; Teploukhov and Fjelstrup died in prison; Zalessky and Ivanov were executed (Karmysheva, 2002; Professora Tomskogo universiteta…, 2003). Archives preserved the results of their work, which show the capacities of the scholars and opportunities given by the integrated approach to archaeological and ethnographic studies practiced in Russia in the early 20th century.

The Fjelstrup’s manuscripts of 1920s reflect the state of Russian Turkic Studies of his time and marked the directions for future research. The topics addressed in them became analyzed only many decades later. Systematic study of the traditional worldview of the Turkic peoples of Siberia has began since the 1960s. In the 1970s, Y.A. Shibaeva studied religious syncretism; comprehensive works of M.S. Usmanova, V.Y. Butanaev, and V.A. Burnakov on shamanism and mythological worldview of the Khakas people were published in the 2000s (Usmanova, 1982; Butanaev, 1986, 2006; Burnakov, 2006, 2010, 2020; and others). Since the 1990s, the academic series “Folklore Heritage of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East” has been published under the auspices of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Several volumes of the series contain the Khakas epic and fairytale tradition. In 1999, the Khakas-Russian Historical and Ethnographic Dictionary, prepared by V.Y. Butanaev, was published (1999). In 2006, in the series “Peoples and Cultures”, the volume “Turkic Peoples of Siberia” came out, which comprehensively described the Turkic indigenous communities of the Altai-Sayan region, including the Khakas people (Tyurkskiye narody Sibiri, 2006).

Much of what Fjelstrup planned in the 1920s has become a part of modern ethnography and ethnology. But comparative historical studies of the Turkic communities of Central Asia, viewed through the dynamics of their development from antiquity to modernity, using linguistics, ethnography, anthropology, and archaeology, have remained relevant until today. A comprehensive integrated approach, which was elaborated by Russian Turkologists in the early 20th century, retained its importance and still determines the prospects of cultural, historical, and ethnogenetic studies of Central Asia.

Список литературы From the history of ethnographic studies in the Yenisei region: F.A. Fjelstrup’s Siberian materials

- Adrianov A.V. 1909 Ayran v zhizni minusinskogo inorodtsa. In Zapiski Imp. Rus. geogr. obshchestva po otdeleniyu etnografii, vol. 34. St. Petersburg: [Tip. V.F. Kirshbauma], pp. 489–524.

- Berezovikov N.N. 2017 Ivan Mikhailovich Zalesskiy (1897–1938) – Sibirskiy ornitolog, khudozhnik-animalist i odin iz sozdateley Tomskogo ornitologicheskogo obshchestva. Russkiy ornitologicheskiy zhurnal, vol. 26 (1481): 3241–3267.

- Burnakov V.A. 2006 Dukhi Srednego mira v traditsionnom mirovozzrenii khakasov. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Burnakov V.A. 2008 Puteshestviye v “mir mertvykh”: Misteriya khakasskogo shamana Makara Tomozakova. Problemy istorii, filologii, kultury, No. 22: 607–617.

- Burnakov V.A. 2010 The Yzykh in the context of traditional Khakassian beliefs. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 2: 111–121.

- Burnakov V.A. 2020 Fetishi-tyosy v traditsionnom mirovozzrenii khakasov (konets XIX – seredina XX v.). Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Butanaev V.Y. 1986 Pochitaniye tyosey u khakasov. In Traditsionnaya kultura narodov Tsentralnoy Azii. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 89–112.

- Butanaev V.Y. 1999 Khakassko-russkiy istoriko-etnograficheskiy slovar. Abakan: Khakasiya.

- Butanaev V.Y. 2006 Traditsionniy shamanizm Khongoraya. Abakan: Izd. Khak. Gos. Univ.

- Efremova N.I. 1972 Obrazovaniye i pravovoye polozheniye Khakasskogo natsionalnogo uyezda. In Aktualniye voprosy gosudarstva i prava. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 3–11. (Trudy Tom. Gos. Univ.; Ser. yur.; vol. 216).

- Fjelstrup F.A. 1926 Svadebniye zhilishcha turetskikh narodnostey. In Materialy po etnografi i, vol. 3 (1). Leningrad: Izd. Gos. Russkogo muzeya, pp. 111–122.

- Fjelstrup F.A. 1930 Molochniye produkty turkov-kochevnikov. In Kazaki. Moscow: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 263–301. (Sbornik statey antropologicheskogo otryada Kazakstanskoy ekspeditsii AN SSSR. 1927 g.; iss. 15).

- Fjelstrup F.A. 2002 Iz obryadovoy zhizni kirgizov nachala XX veka. Moscow: Nauka.

- Gubaeva S.S., Karmysheva B.K. 2002 F.A. Fjelstrup i yego issledovaniya sredi kirgizov. In Fjelstrup F.A. Iz obryadovoy zhizni kirgizov nachala XX veka. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 3–13.

- Karmysheva B.K. 1988 Etnograficheskoye izucheniye narodov Sredney Azii i Kazakhstana v 1920-ye gody (Poleviye issledovaniya F.A. Fjelstrupa). In Ocherki istorii russkoy etnografi i, folkloristiki i antropologii, iss. 10. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 38–62.

- Karmysheva B.K. 2002 Ot tropicheskikh lesov Amazonki do tsentralnoaziatskikh stepey: Zhiznenniy put F.A. Fjelstrupa. In Repressirovanniye etnografy, iss. I. [2nd edition]. Moscow: Vost. lit., pp. 152–163.

- Katanov N.F. 1897 Otchet o poyezdke, sovershennoy s 15 maya po 1 sentyabya 1896 g. v Minusinskiy okrug Yeniseiskoy gubernii. Kazan: [Tipo-lit. Imp. Kazan. Univ.].

- Kiryushin Y.F., Tishkin A.A., Shmidt O.G. 2004 Zhiznenniy put Sergeya Ivanovicha Rudenko (1885–1969). In Zhiznenniy put, tvorchestvo, nauchnoye naslediye Sergeya Ivanovicha Rudenko i deyatelnost yego kolleg. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 9–21.

- Kitova L.Y. 2010 Sergey Aleksandrovich Teploukhov. Rossiyskaya arkheologiya, No. 2: 166–173.

- Klements D.A. 1892 Zametka o tyusyakh. In Izvestiya Vost.-Sib. Otdeleniya Imp. Rus. geogr. obshchestva, vol. XXIII (4/5). Irkutsk: [s.n.], pp. 23–35.

- Kon F.Y. 2019 Osnovaniye Minusinskogo muzeya glazami F.Y. Kona. In Muzeyevedcheskoye naslediye Severnoy Azii: Trudy muzeyevedov XIX – nachala XX veka. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 184–210.

- Kononov A.N. 1972 V.V. Radlov i otechestvennaya tyurkologiya. In Tyurkologicheskiy sbornik. 1971. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 7–15.

- Kormushin I.V., Nasilov D.M. 1978 O zhizni i tvorchestve S.E. Malova. In Tyurkologicheskiy sbornik. 1975. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 5–11.

- Kyzlasov L.R. 1983 V Sibir nevedomuyu za pismenami tainstvennymi. In Puteshestviya v drevnost. Moscow: Izd. Mosk. Gos. Univ., pp. 16–49.

- Levin M.G. 1947 Dmitriy Nikolaevich Anuchin (1843–1923). In Trudy Instituta etnografi i im. N.N. Miklukho-Maklaya. New series. Vol. I: Pamyati D.N. Anuchina (1843–1923). Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 1–13.

- Malov S.E. 1909 Neskolko slov o shamanstve u turetskogo naseleniya Kuznetskogo uyezda Tomskoy gubernii. Zhivaya starina. God 18, iss. 2/3: 38–41.

- Malov S.E., Fjelstrup F.A. 1928 K izucheniyu turetskikh abakanskikh narechiy. Zapiski Kollegii vostokovedov pri Aziatskom muzeye Akademii nauk SSSR, vol. 3 (2): 289–304.

- Molodin V.I. 2015 Ocherki istorii sibirskoy arkheologii. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Naumova O.B. 2006a Arkhiv rossiyskogo uchenogo-etnografa F.A. Fjelstrupa. Vestnik arkhivista, No. 2/3: 196–212.

- Naumova O.B. 2006b Kazakhskiy baksy: Istoriya odnoy fotografi i (publikatsiya materialov F.A. Fjelstrupa po kazakhskomu shamanstvu). Etnografi cheskoye obozreniye, No. 6: 77–85.

- Nekrylov S.A., Fominykh S.F., Markevich N.G., Litvinov A.V. 2012 Institut issledovaniya Sibiri i izuchenye istorii, arkheologii i etnografii regiona (1919–1920 gg.). Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, No. 365: 77–81.

- Professora Tomskogo universiteta: Biografi cheskiy slovar (1980–2003). 2003 Vol. 4 (2). Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.

- Pshenichnaya M.N., Bokovenko N.A. 2002 Osnovniye etapy zhizni i tvorchestva Mikhaila Petrovicha Gryaznova (1902–1984). In Stepi Yevrazii v drevnosti i Srednevekovye: K 100-letiyu so dnya rozhdeniya M.P. Gryaznova, bk. I. St. Petersburg: Izd. Gos. Ermitazha, pp. 19–28.

- Rudkovskaya M.A. 2004 S.I. Rudenko – issledovatel Minusinskoy kotloviny. In Zhiznenniy put, tvorchestvo, nauchnoye naslediye Sergeya Ivanovicha Rudenko i deyatelnost yego kolleg. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 36–42.

- Shibaeva Y.A. 1979 Vliyaniye khristianizatsii na religiozniye verovaniya khakasov (religiozniy sinkretizm khakasov). In Khristianstvo i lamaizm u korennogo naseleniya Sibiri (vtoraya polovina XIX – nachalo XX v.). Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 180–196.

- Simakov G.N. 1998 Sokolinaya okhota i kult khishchnykh ptits v Sredney Azii: Ritualniye i prakticheskiye aspekty. St. Petersburg: Peterburg. vostokovedeniye. Trudy syezda po organizatsii Instituta issledovaniya Sibiri. 1919 Pt. I–IV. Tomsk: [Tip. Sibirskogo Tovarishchestva pechatnogo dela i Doma trudolyubiya]. Tyurkskiye narody Sibiri. 2006 Moscow: Nauka, 2006.

- Usmanova M.S. 1982 Dokhristianskiye verovaniya khakasov v kontse XIX – nachale XX v.: Opyt istoriko-etnografi cheskogo issledovaniya. Cand. Sc. (History) Dissertation. Tomsk.

- Yakovlev E.K. 1900 Etnografi cheskiy obzor inorodcheskogo naseleniya doliny Yuzhnogo Yeniseya i obyasnitelniy katalog Etnografi cheskogo otdela Muzeya. [s.n.].

- Zhurnaly zasedaniy soveta Instituta issledovaniya Sibiri (13 noyabrya 1919 g. – 16 sentyabrya 1920 g.). 2008 Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ. URL: http://vital.lib.tsu.ru/vital/access/manager/Repository/vtls:000341800. Accessed November 29, 2022.