Gender analysis of the Russian labor market

Автор: Panov Aleksandr Mikhailovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Young researchers

Статья в выпуске: 3 (33) т.7, 2014 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The issue of gender inequality in the labor market affects all world countries to some extent. As salary is the basis of population’s sources of income in Russia, unequal pay to men and women for equal work can trigger gender discrimination in the labor market and beyond. The article focuses on the gender analysis of the Russian labor market. It focuses on conjunctural conditions of the labor market in a gender aspect, socio-economic characteristics of men and women as subjects of the labor market and the institutional features of the Russian labor market. The study reveals that, despite lower wages, women, judging by their socio-economic characteristics, possess competitive advantages over men, having higher level of education and better state of health. In addition to horizontal segregation, traditional partition of industries to “male” and “female”, the main causes of gender wage gaps are discriminatory social attitudes and social role of women. The issue to address gender discrimination in the modern Russian society becomes more critical due to contradiction between normative-legal acts, stipulating the gender equality in all spheres of life, and discriminatory social attitudes...

Labor market, gender, wages, inequality, discrimination

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223601

IDR: 147223601 | УДК: 331.2(470) | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2014.3.33.18

Текст научной статьи Gender analysis of the Russian labor market

The issue of gender inequality in the labor market affects all world countries to some extent. It is relevant, because the inequality in the sphere of social and labor relations and, in particular, in the field of labor remuneration, is the basis for economic and social inequality, since salary is one of the population’s main sources of income. For instance, in Russia in 2012 it was 41.5% of the total income of the population [7, p. 170]. Gender inequality can create an economic base for the development of informal institute of gender discrimination, which causes adverse socio-economic consequences. Though rights equality and freedoms of men and women are formally declared, their implementation in practice can be very difficult. It results in unreasonably worse labor conditions for women, reduction in their productivity and economic losses for the whole territory.

The significant number of research and practical work is devoted to the problem in national and foreign literature (R. Kape-lyushnikov, V. Gimpel’son, G. Becker, T. Petersen, V. Snartland, E. Milgrom and others).

The present study analyzes the Russian labor market in the gender aspect, namely: conjunctural conditions of the labor market – economic activity, employment and unemployment, vertical and horizontal segregation; socio-economic parameters affecting employment – education and health state; institutional conditions – legal regulation and social attitudes. The research includes only economically active population, only those men and women that are part of the Russian labor market.

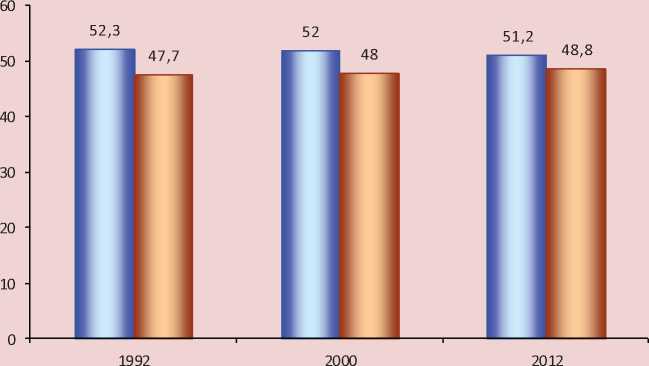

The indicator of the degree of women’s participation in the labor market is the ratio of economically active men and women (fig. 1). This indicator is used by the experts of the World Economic Forum (WEF) to assess the overall access of women to the labor market.

The given data reveal that the proportion of women in the gender structure of the Russian labor market has not undergone significant changes, increased by only 1.1% over a twenty-year period. Thus, men and women take almost equal part in this sphere. According to the “Global Competitiveness Report”, published annually by the WEF, the gender structure of the labor market is Russia’s competitive advantage, ranking 41 by this indicator (among 148 countries) [19, p. 27]. The proportion of economically active women in the labor market in the period of 1992–2012 is almost equal to their proportion in the number of employed population. Therefore, the Russian labor market provides both gender groups with opportunities for economic activity.

This conclusion is confirmed by unemployment indicators in the gender aspect. Today the level of unemployment among women is a bit lower than among men, although the early 1990s experienced no gender differences. Probably, such data are caused by the inaccuracy of statistical measurements, as unemployment an institute was only arising in Russia in that period. However, in 1996 the gap between female and male unemployment was 0.7 p.p. [8, p. 160]. One reason for less unemployment among women is that they often agree on lower wages due to their gender role ( tab. 1 ).

Figure 1. Ratio of men and women in the structure of the economically active population, %

□ Men О Women

Sources: Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2001: stat. sb. [The 2001 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2001, p. 34; Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2005: stat. sb. [The 2005 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2005, p.31; Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. [The 2013 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, p. 41; author’s calculations.

Table 1. Unemployment rates of men and women in the Russian Federation

|

Gender group |

1992 |

2000 |

2012 |

|

Overall unemployment rate, % |

|||

|

Men |

5.2 |

10.2 |

5.8 |

|

Women |

5.2 |

9.4 |

5.1 |

|

Total |

5.2 |

9.8 |

5.5 |

|

Gap between the levels of male and female unemployment, p.p. |

0.0 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

|

Registered unemployment rate |

|||

|

Total number of the unemployed registered with the employment service, thousand people |

61.9 |

1037 |

1064.7 |

|

Number of women registered with the employment service, thousand people |

43.1 |

714.8 |

593 |

|

Share of women in the total number registered with the employment service, % |

69.6 |

68.9 |

55.7 |

|

Average duration of job search, months |

|||

|

Men |

3.9 |

8.6 |

7.4 |

|

Women |

4.9 |

9.7 |

7.7 |

|

Total |

4.4 |

9.1 |

7.5 |

|

Difference in the duration of job search by men and women, months. |

-1 |

-1.1 |

-0.3 |

|

Sources: Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2001: stat. sb. [The 2001 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2001, pp. 160-200, 224-225; Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2005: stat. sb. [The 2005 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2005, pp. 111, 151, 180-181; Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. [The 2013 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, pp. 119, 165, 196; author’s calculations. |

|||

The Russian labor market model stipulates stable employment at low wages [3]. That is, unemployment and wages are not in direct dependence from each other. At the same time the situation can be different in the gender aspect: attracted by, established in the labor market, employers can give preference to women as women’s wages are lower.

The unemployment structure comprises youth unemployment – the share of the 15–29 year old population in the total number of the unemployed. According to our estimates, the level of youth unemployment among women and men is almost the same, respectively 43.4 and 42.9% in 2012 [13, p. 119]. Such a high percentage is caused by economic disadvantages of hiring young people with no work experience. Young women unemployment is complicated by the fact that often the entrepreneur is not economically interested to take social responsibility for their reproductive function, as it concerns provision them with benefits for pregnancy and childbirth, maternity pay and retention of position [2, p. 32]. Such approach influences employment of young women, especially without children, who are in the risk group.

The women position in the labor market is reflected by the level of the registered unemployment: if in the beginning of the transformation period women comprised about 70% of the unemployed registered with the employment service, in 2012 its share fell to 55.7 %. On the one hand, it can indicate stabilization of female employment. On the other hand, it can reveal a higher level of women’s confidence to public institutions, which correlates with the data of empirical studies [4, p. 113]. Moreover, women, remained unemployed, resort to employment services more actively.

As for incomplete unemployment, it does not reveal significant gender inequality: in 2012 women sought work 9 days longer, while in 1992 the gap amounted to one month. Duration of job search reflects the degree of social mobility. Men traditionally have a bit higher degree than women. The situation in the labor market is generally favorable for women due to relatively low wages for their work. With other conditions being equal, women have to either make more efforts to get a well-paid job or to agree to a low-paid one. In addition, they often prefer guaranteed work, albeit with lower wages, since the search for well-paid work is connected with additional costs, which may not be compatible with their social and biological functions.

Obviously, the labor force quality is largely determined by the educational component, the value of which increases due to the requirements of innovative economy [6, p. 62]. To compare the labor force quality of men and women, we have used such factors as the share of men and women with higher and secondary professional education in the economic population structure of Russia ( tab. 2 ).

Table 2. Share of men and women with higher and secondary professional education in the economic population structure of Russia

|

Gender group |

1992 |

2000 |

2012 |

|

Economically active population with higher education |

|||

|

Thousand People |

|||

|

Men |

5717 |

6921 |

10046 |

|

Women |

6140 |

7812 |

12370 |

|

Total |

11857 |

14733 |

22416 |

|

In % |

|||

|

Men |

48 |

47 |

45 |

|

Women |

52 |

53 |

55 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Economically active population with secondary professional education |

|||

|

Thousand People |

|||

|

Men |

10284 |

9195 |

8158 |

|

Women |

13234 |

10886 |

11390 |

|

Total |

23518 |

20081 |

19548 |

|

In % |

|||

|

Men |

44 |

46 |

42 |

|

Women |

56 |

54 |

58 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Sources: Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2001: stat. sb. [The 2001 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2001, p. 37; Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2005: stat. sb. [The 2005 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2005, p. 35; Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. [The 2013 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, p. 45; author’s calculations. |

|||

According to professional education, the structure of female and male labor force varies: the share of women with higher and secondary professional education is traditionally higher than that of men and tends to moderate growth. In the 1992–2012 period the share of women with higher and secondary professional education have increased by three and two percentage points, respectively, amounting to 55% and 58%.

However, despite a higher level of education women lag behind men by level of wages. It is connected with the traditional concentration of women in low-paid sectors of the national economy. Women work in spheres that usually require higher or secondary professional education, continuous retraining and improvement of professional skills, such as health, education, social services sphere, which, traditionally maintained by women. According to G.S. Becker, investments in human capital that comprise the cost of professional education have a high degree of risk and do not always pay off [15]. This statement is true for the Russian labor market. High level of education does not guarantee having a well-paid job, but it provides more opportunities to find a job with better working conditions. Thus, for women, obtaining professional education is often not an investment in future high wages, but a competitive advantage when seeking employment.

According to the WEF “Global Competitiveness Report”, Russia ranks 83 among 133 states by the ratio of wages of men and women. Russian women’s salaries amount to 63% of men’s. This ratio is observed in Slovenia, the Dominican Republic, Cyprus, Senegal and Costa Rica [17, p. 50]. It corresponds to the calculated by Rosstat differentiation in average accrued wages, which for women amounted to 64.1 % of men’s salaries in 2011 [13, p. 460]. And for ten years this gap, reaching 63.2% in 2000, has not decreased [8, p. 357].

However, this method to estimate differentiation is not quite correct. The average monthly salary (including that in the sectoral aspect) does not seem to reflect inequalities in remuneration. In accordance with the International Labor Organization Convention (ILO) no. 100, equal pay to men and women for equal work means establishing wage rates without gender discrimination [5] (with time-based pay system; when there is a piece rate wage system, the same measurement units of output produced).

The estimate of average monthly salary does not reveal the nature of work performed, as it reflects the situation in aggregate labor market. For maximum approximation of the wages evaluation to the category of “work of equal value” male and female workers were grouped by major activities. At the same time, this grouping excludes a factor of vertical segregation (distribution within the official hierarchy).

To eliminate differences in wages caused by the unequal length of time worked (in 2012 the length of a working week for men amounted to 39.4 hours, for women – 36.8 hours [13, p. 110]), we considered an hour as a minimum accounting unit of time.

In 2011, the average hourly wage of women was at the level of 58-85% of men’s salaries who have the same qualification categories ( tab. 3 ).

Women get lower wages in all spheres, with the only exception being the sphere

Table 3. Average hourly wages of men and women in the Russian Federation by major activities in 2011*in rubles, in current prices

To identify objective economic conditions of such differentiation we estimate the parameters of the labor market and compare socio-economic characteristics of men and women that determine the specifics of their work.

Primarily traditional sectoral concentration of women in the national economy structure, i.e. horizontal segregation, leads to gender differences in remuneration. To assess this concentration, we range Russian economy sectors by the share of women workers and average monthly wage ( tab. 4 ).

As noted above, the highest concentration of women is in the economy, characterized by the lowest wages, such as education, health care, social services and trade. There is an exception, the financial sector, having the highest level of wages and relatively high concentration of women. However, this sphere does not a significant impact on aggregate labor market due to the small share of the employees, engaged in the national economy (only 2%) [13, p. 84].

Table 4. Gender structure of the national economy sectors and remuneration in the Russian Federation in 2012, in rubles, in basic prices

|

Economy sector |

Concentration of women |

Wages (exclusive of gender differentiation) |

|||

|

In % |

Range |

In rubles |

In % of average |

Range |

|

|

Education |

81.5 |

1 |

18995 |

71 |

13 |

|

Health care and social services |

79.9 |

2 |

20641 |

78 |

12 |

|

Hotels and restaurants |

77.0 |

3 |

16631 |

62 |

14 |

|

Other community, social and personal services |

69.5 |

4 |

20985 |

79 |

11 |

|

Financial activity |

67.4 |

5 |

58999 |

222 |

1 |

|

Wholesale and retail trade |

61.6 |

6 |

21634 |

81 |

10 |

|

Operations with real estate, lease and provision of services |

41.5 |

7 |

30926 |

116 |

5 |

|

Public administration and military security |

41.3 |

8 |

35701 |

134 |

3 |

|

Manufacturing |

39.9 |

9 |

24512 |

92 |

9 |

|

Agriculture |

36.8 |

10 |

14129 |

53 |

15 |

|

Production and distribution of electricity, gas and water |

28.4 |

11 |

29437 |

111 |

6 |

|

Transport and communications |

27.0 |

12 |

31444 |

118 |

4 |

|

Mining |

20.1 |

13 |

50401 |

189 |

2 |

|

Construction |

14.8 |

14 |

25951 |

97 |

8 |

|

Fisheries |

11.8 |

15 |

29201 |

110 |

7 |

|

Total |

49.0 |

26629 |

100 |

||

Sources: Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. [The 2013 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, p. 87, 436; author’s calculations

The important factor of people’s successful labor activity is the state of their health that determines productivity and labor intensity. To assess the health state of adult population, the World Health Organization (WHO) uses the death rate indicator, calculated as the death probability of people aged 15–60 per 1000 people in the respective age group. This age period is close to the working age period that allows you to estimate the health labor resources (tab. 5). According to the WHO, in 2011 in Russia the death rate among adult men amounted to 351% and among adult women – to 131%.

It indicates that the health state of the Russians is much worse than that of people in developed European countries. Mortality of adult men in Russia is close to that in Kenya (346%) and Eritrea (347%); mortality of adult women – to Libya (134%)

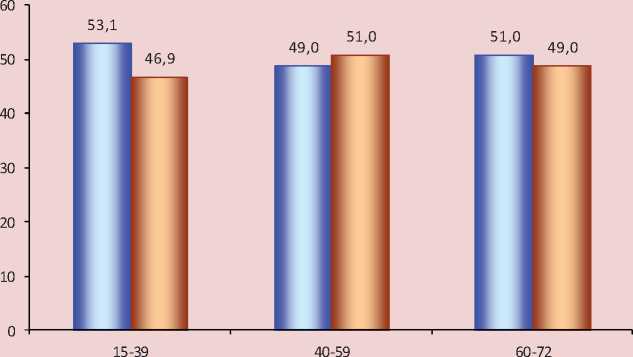

and North Korea (131%). As in most countries women in Russia have a better state of health. Demographic situation in Russia is characterized by a significant gap in the health state of men and women: if the death rate of adult men with corresponds to similar indicators of Sub-Saharan Africa countries, the mortality of adult women in Russia is closer to the countries of Asia, North Africa and the Commonwealth of Independent States. The health state of adult population affects economic activity of different age groups. In 2012 there was the most significant gender disparity in the population group of people aged 15–39: the share of economically active men in the labor market exceeded the share of women by 6.2% and amounted to 53.1% (fig. 2) . In older age groups this ratio stabilized – 51% of the labor market participants aged 40–59 were women.

Table 5. Mortality of adult population (aged 15-60 years) in the world

|

Territory |

1990 |

2011 |

Trend |

|

Men’s mortality |

|||

|

Norway |

128 |

77 |

-51 ▼ |

|

UK |

129 |

91 |

-38 ▼ |

|

Germany |

157 |

96 |

-61 ▼ |

|

Kenya |

395 |

346 |

-49 ▼ |

|

Eritrea |

528 |

347 |

-181 Т |

|

Russia |

318 |

351 |

33 ▲ |

|

Djibouti |

375 |

352 |

-23 ▼ |

|

Women’s mortality |

|||

|

Norway |

65 |

49 |

-16 ▼ |

|

Germany |

77 |

51 |

-26 ▼ |

|

UK |

78 |

57 |

-21 ▼ |

|

Russia |

117 |

131 |

14 ▲ |

|

DPRK |

91 |

131 |

40 ▲ |

|

Libya |

164 |

134 |

-30 ▼ |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

156 |

135 |

-21 ▼ |

|

Sources: World Health Statistics 2013: Statistics Digest. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013, pp. 53-57; author’s calculations. |

|||

Figure 2. Economic activity of men and women in Russia in 2012 (in % of total population of the relevant age group)

□ Men □ Women

Sources: Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. [The 2013 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, p. 41; author’s calculations.

In the population group of people aged 60–72 the share of economically active men exceeded the share of women by 2%, however, this age group comprises only 4.5% of the aggregate labor market.

It should also be noted that the Russian Federation is one of those states, where adult mortality has increased for 1990– 2011.

One of the factors that have a negative impact on the health status of the population is working conditions. In this respect women are in a more advantageous position than men. In Russia in 2012 18.2% of the total number of men employed in the economy worked in harmful and dangerous working conditions, 4.6% – of the total number of women; harmful and dangerous working conditions amounted to 11.2% of the total number of jobs [13, pp. 87, 353-355]. Working conditions of men and women are also different due to gender distribution by types of economic activity: most workplaces with harmful and dangerous working conditions are concentrated in traditionally “male” economy sectors: mining, construction, manufacturing, distribution of gas and water, transport and communications.

Having considered the basic parameters of the labor market and socio-economic characteristics of men and women, we see that nowadays there are no objective characteristics of the female labor force, contributing to segregation in the labor remuneration, as women and men are almost equally presented in the labor market, female unemployment is lower than men’s. Women’s competitive disadvantages are longer job search and youth unemployment. At the same time, women have certain competitive advantages, surpassing men by the level of education and health. Moreover, these benefits are gradually growing: adapting to the requirements of the labor market, seeking to work in more favorable conditions (women are, as a rule, more concerned about their health state than men), women try to get professional education. Often they are unable to use their advantages. Differentiation in labor remuneration of men and women is not being caused by economic, but social and institutional conditions. Women’s social role is caring for children, their upbringing, housekeeping often at the expense of employment and career.

As for institutional reasons, E.V. Bazueva indicates the significant conflict between formal and informal institutions: if the system of formal rules (national and international legislation) guarantee equal rights for men and women in all life spheres, the system of informal rules (customs, traditions, social attitudes) presupposes a secondary position of women [1, p. 56]. In her opinion, in the future Russia expects strengthening of these institutional factors due to the rapprochement of the state and the Orthodox Church, preaching traditional attitudes towards social roles given to each gender [1, p. 55].

The social roles of women are viewed as natural and not discriminatory. No problem arises in case if their performance is voluntary and conscious (a woman gives more time and effort to household chores deliberately). However, if these social roles and attitudes are contradictory to a woman’s personal choice, imposed by the society and create conditions for gender segregation, they become discriminatory and can have adverse socio-economic consequences. The situation can aggravate if the discriminatory conditions in the sphere of informal institutions are in conflict with formal institutions. So, it is problematic to overcome this, only issuing laws that contain direct prohibition on discrimination or different forms of “positive actions”. In our opinion, to achieve equality in the remuneration, women have to make great efforts, increasing gender gap in education and health until women’s socio-economic roles become more required than informal institutional barriers in the Russian labor market.

More convincing evidences of wage discrimination (unequal pay for equal work) on the gender basis are provided with the analysis of the productivity of men and women. However, the Russian statistics service does not estimate labor productivity in the gender aspect. Monitoring of productivity of men and women can become an effective tool to measure gender inequality in the Russian labor market.

Today we have only foreign authors’ scientific and empirical researches on the issue of the gender analysis of labor productivity. According to T. Petersen, V. Snartland and E. Milgrom and others, in developed countries the gap in productivity of men and women of working professions is small and amounts to 3% in Norway, 2% – in the United States and 1% in Sweden [18].

One of the effective ways to overcome gender discrimination is the employers’ transition to the practice of “effective employment contract”, stipulating the use of piecework remuneration forms [18]. The reason for it is that to identify price differences according to sex is much more complicated than according to an hour of time worked, since the finished product is already not a labor force manifested in hours but an impersonal result of its use. But it should be noted that application of the effective contract system would be premature till the Russian population survey’ studying the level of labor productivity is carried out and female productivity is evaluated in sectoral and qualification aspects.

Sited works

-

1. Bazueva E.V. Institutional Environment of Modern Russia: Gender Indicator of Efficiency. Bulletin of the Perm State University , 2011, no. 2 (9), pp. 47-60.

-

2. Berezovskaya G.V. Women in the Labor Market of the City of Ust-Ilimsk: Gender Inequality and Ways of Its Overcoming. Almanac of Modern Science and Education, Tambov: Gramota, 2008. No. 4 (11). In 2 parts. Part 2. Pp. 31-33.

-

3. Kapelyushnikov R. I. The End of the Russian Model of the Labor Market?: Preprint . Moscow: Izd. dom Gosudarstvennogo universiteta Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki. 80 p.

-

4. Kozhina T.P. People’s Confidence in Governmental and Public Institutions: Regional Aspect. Problems of Development of Territories , 2013, no.3(65), pp. 100-115.

-

5. Convention on Equal Remuneration for Men and Women for Work of Equal Value: Adopted on 29 June 1951 at Session 34 of the General Conference of the International Labor Organization. Konsultant Plus: Reference-Legal System .

-

6. Leonidova G.V., Panov A.M. Territorial Aspects of Labor Potential Quality. Problems of Development of Territories , 2013, no. 3 (65), pp. 60-70.

-

7. The 2013 Socio-Economic Indicators: Statistics Digest . Rosstat, Moscow, 2013. 990 p.

-

8. The 2001 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest. Rosstat, Moscow, 2001. 580p.

-

9. The 2005 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest. Rosstat, Moscow, 2005. 502p.

-

10. The 2007 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest. Rosstat, Moscow, 2007. 611p.

-

11. The 2009 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest. Rosstat, Moscow, 2009. 623p.

-

12. The 2011 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest. Rosstat, Moscow, 2011. 637p.

-

13. The 2013 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest. Rosstat, Moscow, 2013. 661p.

-

14. Shabunova A.A., Rossoshanskii A.I. On Gender Wage Differential in Labor Market. Problems of Development of Territories , 2013, no.5 (67), pp. 50-56.

-

15. Becker G.S. A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education (3rd Edition) . The University of Chicago Press, 1994. Available at: www.nber.org/chapters/c11231

-

16. Global Competitiveness Report 2013–2014: Statistics Digest . Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2014. 551p.

-

17. Global Gender Gap Report 2013: Statistics Digest . Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2013. 388 p.

-

18. Petersen T., Snartland V., Meyersson Milgrom E.M. Are Female Workers Less Productive Than Male Workers?: Research in Social Stratification and Mobility . Available at: www.irle.berkeley.edu/.../139-06 . pdf (access date: April 3, 2014).

-

19. World Health Statistics 2013: Statistics Digest . Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. 168 p.

-

20. Bazueva E.V. Institutsional’naya sreda sovremennoi Rossii: gendernyi kriterii effektivnosti [Institutional Environment of Modern Russia: Gender Indicator of Efficiency]. Vestnik Permskogo universiteta [Bulletin of the Perm State University], 2011, no. 2 (9), pp. 47-60.

-

21. Berezovskaya G.V. Zhenshchiny na rynke truda goroda Ust’-Il’minsk: gendernoe neravenstvo i puti ego preodoleniya [Women in the Labor Market of the City of Ust-Ilimsk: Gender Inequality and Ways of Its Overcoming]. Al’manakh sovremennoi nauki i obrazovaniya [Almanac of Modern Science and Education], Tambov: Gramota, 2008. No. 4 (11). In 2 parts. Part 2. Pp. 31-33.

-

22. Kapelyushnikov R. I. Konets rossiiskoi modeli rynka truda?: preprint [The End of the Russian Model of the Labor Market?: Preprint]. Moscow: Izd. dom Gosudarstvennogo universiteta Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki. 80 p.

-

23. Kozhina T.P. Institutsional’noe doverie: regional’nyi aspekt [Tekst] / T. P. Kozhina [People’s Confidence in Governmental and Public Institutions: Regional Aspect]. Problemy razvitiya territorii [Problems of Development of Territories], 2013, no.3(65), pp. 100-115.

-

24. Konventsiya o ravnom voznagrazhdenii muzhchin i zhenshchin za trud ravnoi tsennosti: prinyata 29 iyunya 1951 goda na 34 Sessii General’noi konferentsii Mezhdunarodnoi organizatsii truda [Convention on Equal Remuneration for Men and Women for Work of Equal Value: Adopted on 29 June 1951 at Session 34 of the General Conference of the International Labor Organization]. Konsul’tantPlyus: sprav.-poiskovaya sistema [Konsultant Plus: Reference-Legal System].

-

25. Leonidova G.V., Panov A.M. Trudovoi potentsial: territorial’nye aspekty kachestvennogo sostoyaniya [Territorial Aspects of Labor Potential Quality]. Problemy razvitiya territorii [Problems of Development of Territories], 2013, no. 3 (65), pp. 60-70.

-

26. Regiony Rossii. Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskie pokazateli 2013: stat. sb . [The 2013 Socio-Economic Indicators: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat, Moscow, 2013. 990 p.

-

27. Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2001: stat. sb. [The 2001 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat, Moscow, 2001. 580 p.

-

28. Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2005: stat. sb. [The 2005 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat, Moscow, 2005. 502 p.

-

29. Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2007: stat. sb. [The 2007 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat, Moscow, 2007. 611 p.

-

30. Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2009: stat. sb. [The 2009 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat, Moscow, 2009. 623 p.

-

31. Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2011: stat. sb. [The 2011 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat, Moscow, 2011. 637 p.

-

32. Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. [The 2013 Labor and Employment in Russia: Statistics Digest]. Rosstat, Moscow, 2013. 661 p.

-

33. Shabunova A.A., Rossoshanskii A.I. O gendernoi differentsiatsii zarabotnoi platy na rynke truda [On Gender Wage Differential in Labor Market]. Problemy razvitiya territorii [Problems of Development of Territories], 2013, no.5 (67), pp. 50-56.

-

34. Becker G.S. A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education (3rd Edition) . The University of Chicago Press, 1994. Available at: www.nber.org/chapters/c11231

-

35. Global Competitiveness Report 2013–2014: Statistics Digest . Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2014. 551p.

-

36. Global Gender Gap Report 2013: Statistics Digest . Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2013. 388 p.

-

37. Petersen T., Snartland V., Meyersson Milgrom E.M. Are Female Workers Less Productive Than Male Workers?: Research in Social Stratification and Mobility . Available at: www.irle.berkeley.edu/.../139-06 . pdf (access date: April 3, 2014).

-

38. World Health Statistics 2013: Statistics Digest . Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. 168 p.

Список литературы Gender analysis of the Russian labor market

- Bazueva E.V. Institutsional’naya sreda sovremennoi Rossii: gendernyi kriterii effektivnosti . Vestnik Permskogo universiteta , 2011, no. 2 (9), pp. 47-60.

- Berezovskaya G.V. Zhenshchiny na rynke truda goroda Ust’-Il’minsk: gendernoe neravenstvo i puti ego preodoleniya . Al’manakh sovremennoi nauki i obrazovaniya , Tambov: Gramota, 2008. No. 4 (11). In 2 parts. Part 2. Pp. 31-33.

- Kapelyushnikov R. I. Konets rossiiskoi modeli rynka truda?: preprint . Moscow: Izd. dom Gosudarstvennogo universiteta Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki. 80 p.

- Kozhina T.P. Institutsional’noe doverie: regional’nyi aspekt /T. P. Kozhina . Problemy razvitiya territorii , 2013, no.3(65), pp. 100-115.

- Konventsiya o ravnom voznagrazhdenii muzhchin i zhenshchin za trud ravnoi tsennosti: prinyata 29 iyunya 1951 goda na 34 Sessii General’noi konferentsii Mezhdunarodnoi organizatsii truda . Konsul’tantPlyus: sprav.-poiskovaya sistema .

- Leonidova G.V., Panov A.M. Trudovoi potentsial: territorial’nye aspekty kachestvennogo sostoyaniya . Problemy razvitiya territorii , 2013, no. 3 (65), pp. 60-70.

- Regiony Rossii. Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskie pokazateli 2013: stat. sb. . Rosstat, Moscow, 2013. 990 p.

- Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2001: stat. sb. . Rosstat, Moscow, 2001. 580 p.

- Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2005: stat. sb. . Rosstat, Moscow, 2005. 502 p.

- Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2007: stat. sb. . Rosstat, Moscow, 2007. 611 p.

- Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2009: stat. sb. . Rosstat, Moscow, 2009. 623 p.

- Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2011: stat. sb. . Rosstat, Moscow, 2011. 637 p.

- Trud i zanyatost’ v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. . Rosstat, Moscow, 2013. 661 p.

- Shabunova A.A., Rossoshanskii A.I. O gendernoi differentsiatsii zarabotnoi platy na rynke truda . Problemy razvitiya territorii , 2013, no.5 (67), pp. 50-56.

- Becker G.S. A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education (3rd Edition). The University of Chicago Press, 1994. Available at: www.nber.org/chapters/c11231

- Global Competitiveness Report 2013-2014: Statistics Digest. Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2014. 551 p.

- Global Gender Gap Report 2013: Statistics Digest. Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2013. 388 p.

- Petersen T., Snartland V., Meyersson Milgrom E.M. Are Female Workers Less Productive Than Male Workers?: Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. Available at: www.irle.berkeley.edu/../139-06.pdf (access date: April 3, 2014).

- World Health Statistics 2013: Statistics Digest. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. 168 p.

- World Health Statistics 2013: Statistics Digest. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013, pp. 53-57

- Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, p. 87, 436

- Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, pp. 468-469

- Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2001: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2001, p. 37; Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2005: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2005, p. 35

- Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, p. 45

- Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2001: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2001, pp. 160-200, 224-225

- Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2005: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2005, pp. 111, 151, 180-181

- Trud i zanyatost' v Rossii 2013: stat. sb. . Rosstat. Moscow, 2013, pp. 119, 165, 196