Heuristic potential of concepts by G. Hofstede and A.A. Auzan for studying binarity of culture in Armenia and Russia

Автор: Mkoyan G.S., Golovchin M.A.

Журнал: Logos et Praxis @logos-et-praxis

Рубрика: Социология и социальные технологии

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.23, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

At the present stage of development, culture plays a special role in the life of society as a set of value beliefs and practices, since it is it that shapes the attitude of the population toward the basic rules, norms, and realities, which is somewhat complicated by the spread of polar cultural patterns (binarity) in society. As part of the article, using materials from sociological surveys, we tried to present arguments about how post-Soviet countries are developing in the mirror of the manifestation of binary, which is actively manifested in national culture. In accordance with the theory of A.A. Auzan, we consider binarity culture to be a type of culture built on the structural opposition of the following values: individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, high/low power distance, and tolerance/intolerance to uncertainty. Within Hofstede’s theory, aspects such as individualism/ collectivism, tolerance/uncertainty avoidance, and femininity/masculinity are considered. To illustrate the development of binary culture, two neighboring countries - the Russian Federation and the Republic of Armenia - are examined. In the course of the research, we conducted secondary analysis of the data obtained from public opinion surveys in the city of Yerevan (Republic of Armenia) and in the Vologda Region (Russian Federation). Within the examination, practices supporting the populations of two polar types of cultures have been identified: C-culture and I-culture. In conclusion, we present preliminary conclusions about how the signs of polar cultures manifest themselves in Russian and Armenian society. We are trying to substantiate the idea that for the effective development of the state it is necessary that the process of making decisions important for the life of the population (institutional design) corresponds to the cultural needs of the population. Main research conclusion: culture serves an explanatory function, allowing for the identification of the reasons for the success or failure of managerial decision-making.

Culture, cultural code, binarity, sociological survey, Russia, armenia

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149145694

IDR: 149145694 | УДК: 316.733 | DOI: 10.15688/lp.jvolsu.2024.1.4

Текст научной статьи Heuristic potential of concepts by G. Hofstede and A.A. Auzan for studying binarity of culture in Armenia and Russia

DOI:

While searching for what drives modern development and how to respond to the challenges of the time, economic science has to revise many scientific theories [Golovchin, Leonidova 2014]. Representatives of various scientific schools consider various fundamentals of societal development: accumulation and concentration of capital, its profitability, innovation, biological and natural aspects related to the location of territories, the nature of institutions prevailing in society, human and social capital [Ekimova 2019], etc. Nevertheless, none of these theories provides an unambiguous answer to the question of why, under similar geographical and social conditions, different countries have different levels of economic welfare. Some scholars see a reasonable explanation in focusing on non-economic factors, in particular, culture. Thus, the well-known American sociologist and political scientist Samuel Huntington at the end of the 20th century proclaimed that “culture matters” [Huntington 2001].

What is the practical meaning of Huntington’s idea? Interest in culture is directly linked to the development of a new concept of economic agent within economic theory, “Homo Institutus” [Inshakov 2005]. It is an individual who, in a situation of limited rationality, information asymmetry, and risk, has to implement their economic decisions in some way. Thus, they have to take into account restrictions imposed by laws, rules, traditions, customs, and habits [Inshakov 2005]. The relationship between a “Homo Institutus” agent and a counterparty (the state) is marked by a special role of culture, which is described by the expression “Culture is the mother, institutions are the children” [Huntington 2001]. In other words, members of society, when relying on culture, can either believe in the value of institutions formed by the state (rules, norms, and regulators of public life) or not [Welzel, Inglehart, Ponarin 2012]. If culture does not contradict an institution, then it forms a positive attitude toward it in society. As a result, “Homo Institutus” agents fulfill contractual obligations imposed on them by a counterparty (the state), while the implementation of contractual obligations leads to nationwide economic growth. In science, this interaction is described by the “normal behavior” function of an agent. If culture contradicts institutions, then it forms the negative attitude of an agent (society) toward an institution. As a result, members of society either circumvent the limitations of institutions or switch to a strategy of opportunism imitating the fulfillment of contractual obligations. Consequently, economic activity sometimes results in an increase in transaction costs and a direct conflict with the counterparty (the state). This interaction is described by the “abnormal behavior” function of an agent [Tuzhik, Shulenina, Zaitseva 2015].

In other words, a culture that shapes normal behavior in agents also ensures economic growth in the country. However, to achieve this, it is necessary to create cultural institutions [Golovchin, Leonidova 2014]. Describing the relationship between cultures and institutions, C. Welzel proves that countries with highly developed emancipatory values (pursuit of freedom, human rights) have a much higher level of institutional development [Welzel 2017]. These countries include Japan, Western Europe, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the USA, and part of

Eastern Europe [Welzel 2017]. Scientists believe that the interaction of institutions and culture can lead either to the dominance of culture or to the victory of institutions. As a result, either culture begins to change under the influence of new standards, rules, and norms of modern life or, on the contrary, institutions change because the culture of society does not accept them [Auzan 2022].

In the article, we intend to discuss the meaning of national culture in the lives of postSoviet countries (Russia and Armenia) within the framework of A.A. Auzan’s theory of the cultural code of the economy [Auzan 2022]. Within the discourse started by A.A. Auzan, we are trying to build preliminary arguments about the various manifestations of polar characteristics in the culture of post-Soviet countries: priority in the mass consciousness of personal or group interests; attitude to power from the positions of high and low distance; independence and the need for support from the external environment; narrow and wide horizons for planning future prospects [Auzan 2022].

The purpose of the study is to search for an approach and empirical parameters that reflect the binary nature of national culture in the context of the theories of G. Hofstede and A.A. Auzan. The study presents an analysis of sociological data from surveys conducted in Russia and Armenia, which reveal the cultural characteristics of the population of these countries in the categories of C and I-culture. The scientific novelty of the results obtained lies in the development of tools for the task of analyzing specific manifestations of polar characteristics in the culture of postSoviet countries.

Categorizing cultural “binarity”

Science has many approaches to the term “culture” (there are about 500 definitions). In general, they differ in the ways they describe the very nature of culture and its bearers. Some scholars focus on the personality of an individual, while others consider a certain “collective carrier” of culture (society, nationality, nation). Basically, most approaches boil down to the fact that culture is what an individual has in their mind and what determines their actions. We should also point out an industry-based approach, which studies culture with the help of analyzing the activities of organizations and industries that perform a cultural function [Golovchin, Leonidova 2014].

In our research, we proceed from an understanding of national culture as a set of values and practices that determine the thoughts, feelings, and behavior of members of society in relation to important economic and social regulators (institutions) operating in the country. This understanding differs from the approaches of other scientists who perceive the phenomenon under consideration as having the following aspects: content and form (P. Sorokin), a set of knowledge about the surrounding world (A. Mol), ideas and symbols (O. Spengler), a network of organizations designed to perform cultural functions (A.B. Rudakov), etc. We consider the role of culture in the economic and social space within the “principal-agent” institutional concept based on the idea that if culture does not contradict institutions, then it forms a positive attitude toward them in society [Tuzhik, Shulenina, Zaitseva 2015]. As a result, society fulfills contractual obligations imposed on it by the counterparty (the state), and the implementation of contractual obligations promotes economic growth on a national scale. Otherwise, society simulates the fulfillment of contractual obligations, which leads to an increase in transaction costs [Tuzhik, Shulenina, Zaitseva 2015].

Our study is based on A.A. Auzan’s views on culture. He argues that economic growth is determined by interaction in the “economy – politics – culture” space (the researcher calls this phenomenon “threesome tango”). Politics creates institutions as regulators of public life. In turn, they are supported or not supported by culture, as a result of which economic success is achieved or not achieved. This allows culture to implement the following functions:

-

a) influence the economic success of a nation;

-

b) influence the competitive specialization of a nation;

-

c) influence transformations and reforms in a given country [Auzan 2022].

The role of each of the following categories – politics, culture, and economy – according to A.A. Auzan defines the cultural code of a nation and serves as a prerequisite for economic success based on culture. To “decipher” the cultural code,

A.A. Auzan uses G. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory and distinguishes two types of cultures: “I-culture” and “C-culture”. I-culture is characterized by individualism, high power distance, masculinity, and short-term orientation. C-culture has the following dimensions: collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, femininity, and long-term orientation [Auzan 2022]. To illustrate the impact of culture on economic growth, A.A. Auzan considers two bright examples: the American Economic Miracle (which happened after the end of World War II) and the Chinese Economic Miracle (a later phenomenon that started in the 1990s) [Auzan 2022]. The former was built on the foundation of I-culture (in particular, innovation, rapid growth of patent activity), and the latter on C-culture (mobilization methods of economic management, diligence) [Auzan 2022]. According to A.A. Auzan, in both cases, in different geographical and historical conditions, it was culture that enabled the countries to achieve economic success and a growth of macroeconomic indicators by creating institutions that supported basic values and were unambiguously perceived by the population [Auzan 2022].

A.A. Auzan writes that the binarity of a culture is what hinders it from implementing its mission [Auzan 2022]. Binary culture is a semantic and axiological concept based on the structural opposition of two polar types of cultures. This is why binary culture is often called explosive, since the competition between polar cultures implies defending one’s own norms and values and is fraught with social disintegration [Shorkin 2011]. Binarity in the culture of a nation can be observed in a simultaneous and often paradoxical manifestation of archaic and modern elements in everyday life [Kostyuk 1999]. Currently, signs of the binary can be found primarily in Russian culture. In particular, Russian public consciousness does not fall under the influence of an “integration matrix.” This fact does not allow social solidarity at the micro-level to be combined with legal regulation at the macro-level [Konstantinova 2019]. Consequently, Russian culture has features of both I-culture and C-culture. At the same time, binary culture can develop according to several possible scenarios: 1) tradirovaniye – sensibly combining the elements of an old and new culture while preserving the axiological and semantic core, i.e., tradition; 2) kontrtradirovaniye – further developing a traditional culture by “dismantling” it and filling it with new content; 3) posttradirovaniye – replacing traditional values by elements of a new culture [Timoshchuk 2018; Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022]. In other words, C-culture and I-culture can be synthesized, coexist, and “keep pace with each other,” or they may conflict, which leads to a “cultural revolution” entailing a dramatic change in societal patterns in one direction or another.

The discourse about the manifestation of the phenomenon of binary in the culture of the population is also supported by L.K. Kruglova, T.P. Berseneva, A.D. Shorkin, A.A. Ibraimov, and A.V. Loparev. They write that binary culture is a semantic and value formation based on the structural opposition of two polar types of cultures, the interaction of which can be explosive [Shorkin 2011].

Thus, the ideas of Hofstede and Auzan are interconnected. Thus, in his works, A.A. Auzan combines the theory of G. Hofstede with the hypothesis of binary cultures. In particular, on the basis of G. Hofstede’s parametric model, he proposes to study the manifestations of two binary oppositions: C and I cultures. However, the scientist does not offer tools for such measurements and does not specify by what parameters representatives of the C and I cultures are determined. In our work, we intend to eliminate this shortcoming.

At the same time, binarity is quite a common phenomenon with regard to culture. What really matters is the nature of the interaction between polar cultures, whether it is synthesis or conflict. In the article, within cross-cultural research, we discuss possibilities for the development of binary culture in Russia and Armenia. We have chosen these countries because their socio-economic development has a “spiral effect,” which means that the standard of living and quality of life should de facto become incentives for a new round of economic development, but their struggling economies cannot ensure high living standards and quality of life for their population so far [Golovchin, Leonidova 2014]. In particular, this is evidenced by the World Happiness Report 2018, a survey conducted by the UN in the course of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network initiative [Helliwell, Layard, Sachs 2018]. The survey contains rankings of countries with the most favorable living conditions; Russia, ranking 59th, and Armenia, ranking 129th, are in the second part of the survey (lagging considerably behind Finland and Norway, who top the rating) [Helliwell, Layard, Sachs 2018]. Thus, a vicious circle is formed; getting out of it requires a strategic approach to achieving economic goals and taking into account the dynamics of cultural genesis [Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022].

Research methodology

In the study, we are trying to determine to what extent the theory of binary reveals the state of the culture of the population that has formed in the post-Soviet space. To do this we have developed a matrix that specifies the characteristics of binary in two dimensions: cultural traits and polar types of culture (Table). Thus, each cultural peculiarity (according

Operationalization of the concept of “culture” in research

|

Traits of culture |

С-culture |

I-culture |

|

1. Power distance |

Sacralization of power: the state is valuable in itself; it has unconditional authority and is not subject to criticism |

Attitude to power as an “equal player”: the state is valid only when it serves the interests of the individual and society; it may be subject to criticism |

|

2. Priority of personal and group interests |

Collectivism: the meaning of life is to create conditions for one’s own well-being |

Individualism: the meaning of life is to support the environment |

|

3. Attitude towards |

Uncertainty avoidance: fear of what might happen in the future; social pessimism associated with the belief that life will not improve in the future |

Acceptance of uncertainty (tolerance): lack of fear of the future; social optimism, hope that life will be better in the future |

|

4. Gender mentality |

Femininity: the need for support from the state and environment; paternalism |

Masculinity: autonomy and independence; hope that in a difficult life situation only one’s own strength will help |

Note. Suggested by the authors based on the developments of G. Hofstede and A.A. Auzan.

to G. Hofstede) corresponds to two parameters for each binary opposition (according to A.A. Auzan).

The information basis for testing the model of A.A. Auzan presented data from a secondary analysis of sociological surveys conducted among the population of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Armenia. The survey of the population of the Russian Federation was conducted in December 2022 in the Vologda Region and the population of Armenia in the city of Yerevan. The survey method is a survey at the respondents’ place of residence. The sample size is 1,500 people aged 18 years and older. The sample was compiled in accordance with the general population: in the Vologda Region, 1,128.8 thousand people; in Yerevan, 1,092.8 thousand people. The sampling is a quota. Quotas are given in proportions between the urban and rural populations, as well as the gender and the age-sex structure of the adult population of the region [Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022]. The proportion of men aged 18–29 years in the sample was 7.4%, those aged 30–59 years 26.5%, and those aged 60 years and older 10.8%; the proportion of women aged 18–29 years was 6.9%, those aged 30–54 years 23.6%, and those aged 60 years and older 24.9%.

As part of the first stage of the study, data was collected on the life values and attitudes of the population of the two countries [Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022]. Despite the fact that the tools use questions in different formulations, their content is fully consistent with the discourse about the features of national cultures. As part of the second stage, the survey data was interpreted in the categories of dimensions of national culture proposed by G. Hofstede: power distance, individualism/collectivism, tolerance/uncertainty avoidance, femininity/masculinity [Hofstede 2001]. On the third stage, the respondents included in the sample were grouped according to the characteristics of the oppositions of binary cultures proposed by A.A. Auzan: C-culture (high power distance, collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, feminine culture) and I-culture (low power distance, individualism, tolerance of uncertainty, masculine culture) [Auzan 2022]. Thus, in the course of our generalizations, we do not directly resort to the evaluative indicators of G. Hofstede’s parametric model for measuring cultures but try to build reasoning around the characteristics of national culture that were reflected in the data of two surveys. Therefore, the conclusions obtained are preliminary. We do not concentrate on finding an answer to the question of what the culture of Armenians and Russians is, but intend to draw attention to the non-linearity of social development in the two countries under study, which is formed due to the presence of semantic oppositions in national culture [Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022]. We need such conclusions to formulate a hypothesis, which will subsequently form the basis for further research.

As part of the empirical measurements, the populations of Russia and Armenia were asked questions with different wording since different questionnaires were used. The reasons for this are that the initially used tools were not designed for the task of diagnosing the features of national culture. Despite this, the questionnaires still contain questions that provide a sufficient amount of information about the manifestation of the monitored parameters of binary oppositions: the need for leadership from above and a love of freedom; collectivism and individualism in life goals; avoidance and acceptance of uncertainty; and femininity and masculinity. At this stage of the study, we would first of all like to consider whether a binary culture manifests itself in the countries under study. We are aimed primarily at forming working hypotheses, not conclusions.

In the article, we do not directly compare the data obtained for the Vologda Region and Yerevan but analyze the presence of features of polar cultures in Russia and Armenia separately. We just want to draw attention to the possibility of cross-country cultural research based on the concept of binary. We will need observational generalization in the further development of working hypotheses, as well as research tools for determining whether the population belongs to the types of polar cultures.

Research results

In accordance with A.A. Auzan’s model, we summarized the features of C- and I-cultures in the populations of both countries and found binary features in the national cultures of both Russians and Armenians. Next, we dwell on how certain features are reflected in polar cultures.

Russian Federation

Priority of individual and group interests is a cultural feature reflecting the degree to which people in a country prefer to act as individuals rather than as members of groups [Hofstede 2001]. In the model of A.A. Auzan and G. Hofstede, the priority of interests is determined by the binary opposition “individualism versus collectivism.” Individualism is a feature of I-culture and collectivism – C-culture [Auzan 2022].

We determined the type of culture according to the individualism-collectivism dimension with the help of a question about an individual’s life priorities [Auzan 2022]. It was important for us to find out whether one’s life priorities had the nature of post-materialistic values (striving for the support of the environment and well-being).

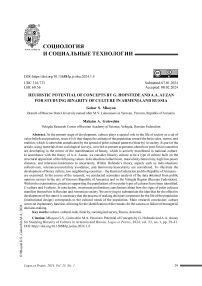

In Russia, respondents’ opinions on this subject are formed with a bias toward I-culture (Fig. 1). In choosing whether to take care of their own health or the well-being of people around them, the majority (88%) tend to choose samples of I-culture (Fig. 1).

Power distance is also a very important characteristic of national culture. In our research, this parameter is determined by the binary opposition “low power distance – high power distance.” In countries with low power distance (Malaysia, South American countries, Arab countries, Indonesia, India, Russia, etc.), social relations are built on the unquestioning authority of the state, and its representatives often have a sacred status. In countries with low power distances (USA, Austria, Israel, Denmark,

New Zealand, etc.), representatives of power do not have special privileges and are treated as ordinary members of society [Rogotneva 2013].

To determine the type of culture in accordance with the above parameter, we analyzed the answers to questions about the nature of power: “What does the state mean to you?” (in the Republic of Armenia) and “Do you consider the incompetence of the authorities a problem of modern life?” (in the Russian Federation).

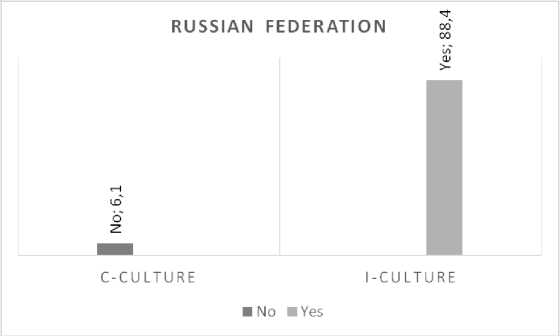

The sociological cross-section shows that in the countries under consideration, people’s spiritual lives gravitate toward high power distance, i.e., examples of C-culture [Auzan 2022]. The share of Russians among those who see the root of societal problems in the incompetence of the authorities (which is typical of I-culture) is low, and the share of those seeking other explanations (C-culture) is high (93%; Fig. 2).

Another important and, in many ways, universal dimension for assessing national culture is gender mentality, which allows an individual to identify themselves and their personal qualities based on gender (sexual) aspects. The structure of gender mentality includes deep (archetypal) and external (socially conditioned) stereotypical structures that determine the attitude toward the environment from the standpoint of masculinity or femininity. These structures include emotions, experience, and character, as well as ways of thinking and interpersonal interaction [Churkina 2020], etc. I-culture is characterized by the prevalence of masculinity; C-culture – femininity.

Fig. 1. The purpose of life is to take care of my own well-being and health (% of respondents in the Vologda Region)

Note. * – Hereinafter, within the survey, respondents were provided with other answer options.

To determine the type of culture according to the “masculinity vs. femininity” dimension, we analyzed the answers given by Russians and Armenians concerning their need for support [Auzan 2022]. The need for support and paternalism corresponds to the feminine type of culture; self-sufficiency and independence corresponds to the masculine type.

Sociological data show that manifestations of feminine culture are typical for Russia. For example, Russians are more likely to say that they cannot survive without external support (58%). At the same time, there are much fewer people who are ready to cope with life’s difficulties without support from the state (Fig. 3).

Attitude toward uncertainty is the most psychological construct in the theory of the cultural code of the economy. This dimension reflects the level of anxiety observed in society due to an increase in threats and unknown and uncertain situations. The Australian scientist N. Harding considers tolerance for uncertainty as a criterion of national differences. He proved that in countries where independent decision-making is condemned for some reason, tolerance for uncertainty is lower, and people have a fear of the future [Harding, Ren 2007]. Basically, low tolerance for uncertainty is a distinctive feature of the current postmodern society, which many scientists call a “risk society”. In the 1980s, the British anthropologist M. Douglas defined the

Fig. 2. What problems of modern life do you consider the most pressing: option – incompetence of the authorities? (% of respondents in the Vologda Region)

RUSSIAN FEDERATION

I won’t survive without the support of the state;

57,7

I don’t need support from the state; 21,0

C-CULTURE

I-CULTURE

-

■ I won’t survive without the support of the state

-

■ I don’t need support from the state

Fig. 3. How much do you personally need the support of the state today? (% of respondents in the Vologda Region)

impact of the risks of modern society on culture in the following way:

– individualistic cultures are built on people’s self-confidence, which allows them to overcome risks and hope for a better future;

– collectivist cultures tend to view nature as fragile and in need of protection, so their representatives constantly feel in danger, are anxious about protecting their borders, and “live for the day” [Douglas, Wildavsky 1982].

To assess the degree of tolerance for uncertainty, we used questions about one’s views in relation to future prospects: “Do you feel fear of the future?”. We consider fear of the future a sign of C-culture and confidence in the future – I-culture.

In fact, the survey showed that Russia is a country with a low level of uncertainty avoidance, which is primarily typical for I-culture (Fig. 4). Russians are less likely to fear the threats of tomorrow (72%). Signs of tolerance for uncertainty are characteristic of less than a third of the population.

Republic of Armenia

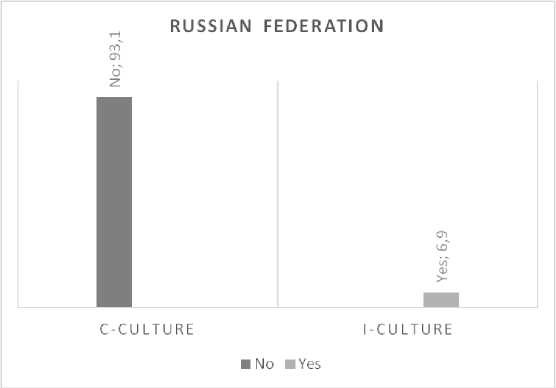

The Armenian population makes choices in favor of personal rather than collective goals (Fig. 5). Thus, when implementing their life plans, Armenians are less inclined to seek support from their environment (9%).

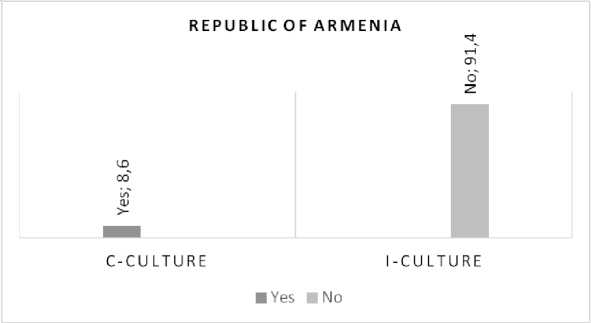

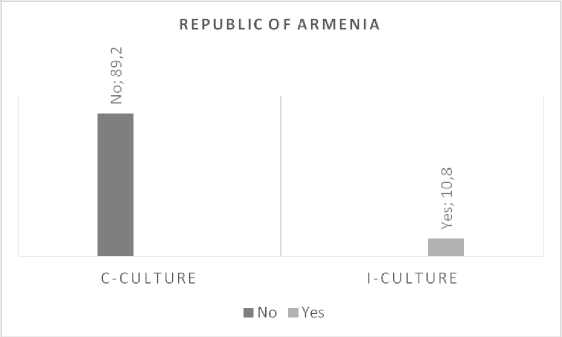

Armenia is characterized by faith in the authority of the government against a backdrop of high power distance. The majority of Armenians (89%) believe that the government cannot focus on the interests of one particular person (Fig. 6).

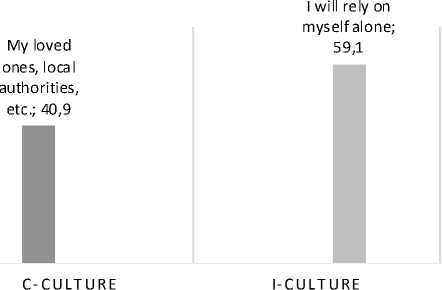

Armenian culture is closer to the models of masculinity (I-culture). Thus, Armenians are much less likely to rely on the help of others (Fig. 7). Less than half of respondents will seek support from relatives or the state.

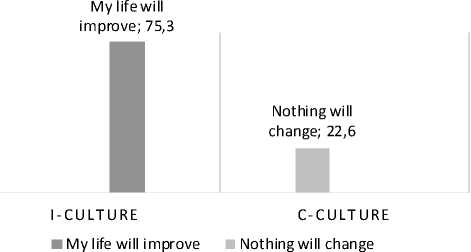

The population of Armenia is less characterized by fear of the future (Fig. 8). Armenians are more likely to have optimistic views on the future (75%), and only 23% believe that nothing will change.

Fig. 4. Do you feel afraid of what is about to happen? (% of respondents in the Vologda Region)

Fig. 5. My life’s goal is to have the support of my environment (% of respondents in Yerevan)

Thus, on the basis of the surveys, we see that Russian and Armenian societies have several types of cultures. National culture in these countries can be described as binary, which means it is not influenced by the “integrative matrix” typical for Western cultures [Konstantinova 2019].

At the same time, cultural features of Armenians and Russians are now synchronously flowing into both C-culture (this primarily concerns power distance) and I-culture (priority of interests, attitude toward uncertainty), which generally indicates the cultural closeness of the two nations.

Fig. 6. My interest in the state depends on the extent it fulfills my needs (% of respondents in Yerevan)

REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA

■ My loved ones, local authorities, etc. ■ I will rely on myself alone

Fig. 7. Who would you turn to, if you had to protect your interests? (% of respondents in Yerevan)

REPUBLIC OF ARMEN IA

Fig. 8. How will your life change in five years? (% of respondents in Yerevan)

We should point out that rather than focusing on the value of each identified feature relating to a particular polar culture, we attach more importance to the very fact of the coexistence of C- and I-cultures in society [Auzan 2022]. This provides insights into the advances and failures of economic institutions and the extent of the consolidation of society.

Discussion

The study improved the theoretical approach of A.A. Auzan, according to which the culture of the population is considered in the context of the existence of two binary oppositions: C and I-culture. As part of the scientific search, we proposed a set of indicators suitable for assessing the belonging of social characteristics of the population to polar cultures according to the parameters that were proposed in the works of G. Hofstede: power distance (sacralization of power and attitude toward power as an “equal player”), priority of personal and group interests (collectivism and individualism), attitude towards uncertainty (avoidance and tolerance for uncertainty), gender mentality (femininity and masculinity). Currently, the binary nature of culture is rather a hypothesis, which in a number of cases is confirmed by the thinking of the population of post-Soviet countries.

The results of measurements in Russia and Armenia indicated the possibility of considering binary culture as an object of research. However, for more thorough conclusions, it will be necessary to conduct one more measurement in each country using the same toolkit. This will make it possible to accurately determine what type of culture is typical for respondents with a certain set of social characteristics.

As a result, we can judge the presence of binary oppositions in the cultures of Armenians and Russians, which allows us to put forward the following hypothesis: the inconsistency of the cultural development of post-Soviet countries requires that the formation of new ideas and meanings that fill the lives of society take into account the cultural characteristics and preferences of different segments of the population [Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022]. In this regard, the effectiveness of public administration directly depends on the extent to which new institutions (regulators) will be supported by the culture of a particular part of society [Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022]. The next stage of our research will be aimed at verifying this hypothesis. The prospects for its development are seen in the implementation of a number of steps:

– the operationalization of the concept of “culture” as a binary phenomenon and the identification of clear signs of belonging to polar cultures;

– conducting a survey among the population of the Republic of Armenia and the Russian Federation using the same toolkit and research scheme to identify the population’s belonging to a particular culture [Mkoyan, Golovchin 2022];

– generalizing cultural traits into a social portrait of the “C-population” and “I-population” using the index technique, which in turn will make it possible to make a more reasonable judgment about the factors that form the cultural code of the nation [Auzan 2022].

In general, having analyzed the sociological research materials, we see confirmation of the signs of binarity in Russian and Armenian cultures. This binarity, according to A.A. Auzan, does not currently allow the cultural code to be used for the benefit of the national economy and, in general, makes the development of institutions dependent on the decisions adopted in the past (science calls it “path dependence”). According to A.A. Auzan, such decisions include autocracy, serfdom, and communality [Auzan 2022].

What should be the culture and cultural code of a nation so that it can achieve economic success and institutional effectiveness? From A.A. Auzan’s perspective, it should be built on the following principles: high power distance, high uncertainty avoidance, feminine mentality, longterm orientation, and the ability of the nation to mobilize forces [Auzan 2022]. The surveys conducted in Russia and Armenia show that in some cases there is a smooth transition to these very cultural traits (it is especially noticeable in Russia) [Welzel 2017]. However, it seems that tolerance for uncertainty is an important resource that should be preserved on the way toward the formation of a cultural code. The attitude toward the future is seen as the most conflicting and alarming feature of binary culture, especially against the background of current challenges. Therefore, the attitude toward uncertainty is the factor that may intensify the binary nature of culture and hinder social consensus and integration [Hofstede 2001].

The greater the number of risks and bad news, the more often the future is perceived as something uncontrollable and inevitable. In addition, low tolerance for uncertainty suppresses the willingness to act effectively and work under risky conditions, reducing the nation’s ability to mobilize in the short term. This may cause an unfavorable “ripple effect” in the future. Currently, it is necessary to consider which institutions will be supported by a population that is tolerant or intolerant of uncertainty.

We should note that an image of the future as a kind of uncertainty is formed most likely as a response to the growing risks of modern society, including the “civilizational conflict” typical of the postmodern era [Welzel 2017]. For example, the results of the military conflict in Karabakh (Artsakh) had a strong impact on society and were reflected in views on social development, progress, and the future. Reflecting on the results of the military conflict has led the population to pay more attention to the development of institutions in the economy, education, national security, etc. New mechanisms began to be proposed that affect the systematic solution of the problems accumulated in the state. One of these mechanisms is social entrepreneurship, which helps solve problems through social activity and the self-organization of citizens.

In this regard, it seems that the current governmental policy of both countries (especially Russia) pays insufficient attention to trust and social capital as a resource for overcoming intolerance to uncertainty in society. It is desirable that social capital become part of both public policy and corporate culture. To achieve this, first of all, it is necessary to cope with a set of strategic issues:

– at the macro level: transformation of moral values, absence of a unified social ideology, flaws in legislation and legal norms, atomization and individualization of consciousness, inequality in citizens’ access to material, social, and cultural goods [Igumnov 2020];

– at the meso and micro levels: deviation from the rules of fair competition, low level of social responsibility, increased interpersonal and institutional distrust, weakening of family values, aggressive expansion of consumer culture [Igumnov 2020].

Список литературы Heuristic potential of concepts by G. Hofstede and A.A. Auzan for studying binarity of culture in Armenia and Russia

- Auzan A.A., 2022. Cultural Codes of the Economy: How Values Affect Competition, Democracy and Welfare. Moscow, AST Publ.

- Churkina N.A., 2020. Gender Mentality as the Basis of a Person’s Gender Identity. Obshchestvo, politika, finansy. Novosibirsk, Izd-vo Sibir. gos. un-ta telekommunikatsii i informatiki, pp. 188-191.

- Douglas M., Wildavsky A., 1982. Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technical and Environmental Dangers. Berkeley, University of California Press.

- Ekimova N.A., 2019. In Search of Social Development Factors: From Monocausal Concepts to Polycausal. Voprosy regulirovaniya ekonomiki=Journal of Economic Regulation, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 6-21.

- Golovchin M.A., Leonidova G.V., 2014. Socio-Cultural Characteristics of the Modern Youth: Some Results of the Pilot Study. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, no. 5 (35), pp. 113-126. DOI: 10.15838/esc/2014.5.35.8

- Harding N., Ren M., 2007. The Importance in Accounting of Ambiguity Tolerance at the National Level: Evidence from Australia and China. Asian Review of Accounting, vol. 15 (1), pp. 6-24.

- Helliwell J., Layard R., Sachs J., 2018. World Happiness Report 2018. New York, Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Hofstede G., 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage.

- Huntington S., 2001. Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress. New York, Basic Books.

- Igumnov O.A., 2020. Russian Organizations Social Capital Formation External Factors. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya 18, Sotsiologiya i politologiya, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 149-172. DOI: 10.24290/1029-3736-2020-26-3-149-172

- Inshakov O.V., 2005. Homo Institutius – Institutional Man. Volgograd, Izd-vo VolGU.

- Konstantinova L.V., 2019. Integration Potential of Society: A Conceptualization. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya, iss. 8, pp. 19-29. DOI: 10.31857/S013216250006133-9

- Kostyuk K.N., 1999. Archaic and Modernism in Russian Culture. Sotsiologicheskii zhurnal, no. 3 (4), pp. 5-20.

- Mkoyan G.S., Golovchin M.A., 2022. Traditional and New Culture in the Post-Soviet Space: Synthesis or Coexistence? Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Kulturologiya i iskusstvovedenie, no. 47, pp. 105-119. DOI: 10.17223/22220836/47/9

- Rogotneva E.N., 2013. The Influence of Power Distance on Peoples’ Relationships in Society. Teoriya i praktika obshchestvennogo razvitiya, no. 5, pp. 57-62 .

- Shorkin A.D., 2011. Postbinary Structure: Lively Game of Binary Oppositions. Uchenye zapiski Krymskogo federalnogo universiteta im. V.I. Vernadskogo. Sotsiologiya. Pedagogika. Psikhologiya, no. 3-4, pp. 8-20.

- Timoshchuk A.S., 2018. Traditional Culture: Essence and Existence. Vladimir, Vladimir Law Institute of Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia.

- Tuzhik A.M., Shulenina D.I., Zaitseva E.V., 2015. The Problem of the “Principal-Agent” and How to Resolve it. Ekonomika i sovremennyi menedzhment: teoriya i praktika, no. 10-11 (53), pp. 102-108.

- Welzel C., 2017. Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation. Moscow, VTsIOM Publ.

- Welzel C., Inglehart A., Ponarin E.D., 2012. Disentangling the Culture-Institution Nexus: The Case of Human Empowerment. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsial’noi antropologii, no. 4, pp. 12-43.