Kainar: a late 18th to early 20th century ritual and housing complex in the Northern Ustyurt

Автор: Azhigali S.E., Turganbayeva L.R.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146401

IDR: 145146401 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2021.49.4.109-119

Текст статьи Kainar: a late 18th to early 20th century ritual and housing complex in the Northern Ustyurt

One of the forms of shifting to a semi-nomadic and semi-sedentary lifestyle among the nomadic Kazakhs of the Aral-Caspian region in the 19th century was the emergence of stationary settlements of a new type, which included necropolises (cemeteries), mosques, and madrasahs, as well as permanent dwellings. In scholarship, they have received the name “ritual and housing complexes” (RHC). The main area where these settlements appeared was the northern Ustyurt (Donyztau). A number of important natural and historical conditions in this region, such as the opportunity for the development of haymaking and land cultivation, presence of ecological niche-shelters in the form of large ravines along the chink cliffs of the plateau, abundance of building stone, etc., played a key role in the context of general historical prerequisites. After existing for almost a hundred years, during the collectivization in the 1930s, RHCs (over thirty in number) were abandoned, but have miraculously survived as monuments of the past culture, and today these constitute a kind of “architectural and archaeological reserve”. Study of them sheds new light on: the culture and social history of nomadic cattle breeders who lived in the Aral-Caspian Sea area

in the Modern Age; specific aspects of the transition of steppe inhabitants to a semi-sedentary lifestyle; the history of popular architecture and the stone-cutting art of the Kazakhs; and the spread of the Islamic religion as an ideology in the nomadic environment. This article analyzes the most typical site—the Kainar ritual and housing complex.

The first information about Kainar appeared in the “Atlas of the Orenburg Land” of 1869, where the complex was marked as “The House of the Ishan” (Atlas…, 1869: Fol. XII-3). In 1892, the site was mentioned in a report of the scientific expedition to the Ustyurt by geomorphologist S.N. Nikitin (1893: 78). In 1904, geobotanist V.A. Dubyansky (1904) worked in the Donyztau area and took photographs of individual ritual and housing complexes. We also find an important mention of that site in a memorial song (zhoqtau) on the death of Doszhan-Ishan Kashakuly (1896), the founder of the settlement, by the Kazakh poet Kerderi Ábubákir (1993: 148–149). In 1962, the Kainar complex was studied by the Guryev (Emba) Expedition from the Institute of History, Archaeology, and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR (headed by K.A. Argynbayev), when ethnographic evidence was collected along with primary documentation of the site (see (Argynbayev, 1987: 113)). In the same period, the Kainar necropolis was examined by the geographer S.V. Viktorov (1971) from the point of view of applied science, for statistical calculation of clan symbols. Targeted study of the Kainar RHC was carried out by the West Kazakhstan Integrated Ethno-Archaeological Expedition headed by S.E. Azhigali in 1987, 2005, and 2007. In the last field season, a complete comprehensive survey of the site was conducted, including instrumental survey, detailed photographic recording, architectural measurements, study of epigraphy, and panoramic photography from a hang glider (R. Sala, J.-M. Deom).

History of emergence of the Kainar RHC

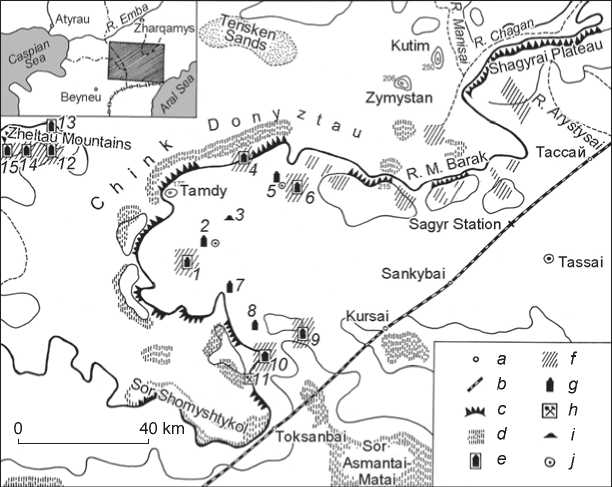

The Kainar ritual and housing complex is located in the western part of the Northern chink cliff of the Ustyurt (Donyztau), in the present-day Atyrau Region (in its southeastern corner), 61.5 km south of the nearest village of Diyar (Baiganinsky District of the Aktobe Region). The name of the site is associated with attributes of the area, where springs (Kazakh ‘qainar’) were located. The site is located on the northern branch of the large Tasastau ravine ( sai ) (Fig. 1), in a relatively low area covered with hills. There is a channel of a stream overgrown with greenery to the southeast of it, and a high-water well is available 1 km to the north.

The initial emergence of the site was obviously associated with a small family cemetery that was used there in the second half of the 18th to early

Fig. 1 . Location of ritual and housing complexes in the northern Ustyurt, Kainar complex, and the adjacent monuments.

1 – Kainar; 2 – Tasastau; 3 – Kyzyluiyk; 4 – Bespai; 5 – Tushshchy-airryk; 6 – Ashchy-ayryk; 7 – Aksaimola; 8 – Okim-Kiik; 9 – Tolebai; 10 – Sultan-akyn; 11 – Toksanbai; 12 – Sherligul; 13 – Egindybulak; 14 – Sholabai; 15 – Kolbai.

a – settlement, railway station; b – railway; c – edge of the Ustyurt, chink cliffs; d – sor , salt lake; e – RHC; f – area of RHC; g – necropolis, cemetery; h – old settlement; i – burial mound; j – well.

19th centuries, next to which later, in the 1840s, a permanent settlement with a mosque (madrasah) appeared. Its founder was a representative of the Muslim clergy from the Shomyshty-Tabyn Kazakh clan (subclan of Karakoily, unit of Konyr) named Doszhan (Dostmukhammed*) Kashakuly (1812–1896)**. The biographical information about Doszhan-Ishan, who is also popularly known as Doshcheke or Doseke, is rather fragmentary and sometimes contradictory. He was born into a religious family: his father Kashak was a mullah, who apparently gave his son a primary education (reading and writing in Arabic, etc.). It should be mentioned that the family belonged to the group of nomadic Kazakhs of the Aral-Caspian Sea region (the large clans of Adai, Tabyn, and Shekty), which had long been under the strong political, cultural, and ideological influence of the Khiva Khanate, whose border until the mid 19th century passed to the north of the Ustyurt. The area on the lower reaches of the Amu Darya River, where in some harsh years the local Kazakhs, primarily the Tabyns, migrated, was known among them as Beskala (‘five towns’) and was considered to be the center of Islamic religion and religious education (as also was the neighboring Bukhara).

It seems that Dosmukhambet Kashakuly received a serious religious education in the madrasah of Khiva, which is also confirmed by his subsequent title of “Ishan”***, typical of the Muslim-Sufi tradition of Central Asia. This is also indicated by the architecture of ritual complexes and mosques, which he later created in Kainar and on Shiylisu using Central Asian architectural traditions and construction techniques, such as domed vaults (including specific barrel vaults), structures under the domes, etc. According to the memorial song of Kerderi Ábubákir, Doszhan’s pir (mentor) was Oldan (ishan) (1993: 148). However, there is information on his training in the madrasah of Orenburg, namely in the Tatar settlement of Kargaly (Salqynuly, 2006: 17–18), which seems to be insufficiently well-confirmed. For such an early period (late 1820s–1830s), it was more natural for a person from the Ustyurt to receive religious education in Khiva (or Bukhara). Obviously, since that time, Doszhan Kashakuly already began his religious and educational activities among the nomadic population (teaching children Arabic letters and other subjects in aul mektebahs, etc.) and acquired a certain status, as evidenced by his personal seal dated to 1832/33. At the same time, he studied at the madrasah, which he might have graduated during this decade.

The next important stage in the life of Doszhan-Ishan was construction of a mosque and arrangement of a settlement in the Kainar area in the northern Ustyurt. According to the memorial song of Kerderi Ábubákir, this happened “some time around 1850” (1993: 148). The ethnographer Argynbayev, who visited the site and conducted surveys in 1962, also tended to agree with the early dating of this event and suggested that the mosque was erected there in the first half of the 19th century (1987: 113). The available data (including specific features of grave structures at the necropolis) indicate the construction of the settlement and mosque in the period from the second half of the 1840s to the early 1850s. By that time, Doszhan Kashakuly had already become a serious religious figure and spiritual enlightener, whose main task was to spread Islam and religious education among nomadic cattle breeders in the southern part of the area inhabited by the Kazakhs of the Junior Zhuz. Apparently, he undertook the construction of the mosque and organization of the madrasah in Kainar after his Hajj to Mecca, which was vaguely mentioned by some of our informants, for example, by Taganov Ashykgali (born 1903, settlement of Kosshagyl in the Guryev Region; record of 1989). Ashykgali suggested that he went on his early pilgrimage together with another well-known religious figure Nurpeke-Ishan (see also (Adzhigaliev, 1994: 58, nt. 15))*. It is believed that Doszhan-Ishan fulfilled only three Hajjes; two of them were later, in the 1870s.

The idea of spreading Islam over a vast area determined the choice of a place for the settlement at the junction of nomadic routes used by the main inhabitants of the Ustyurt and Mangystau—the Tabyn and Adai Kazakhs, not far from the area of spring floods of the steppe rivers Shagan and Manisai, with the opportunity for haymaking twice a year. Natural conditions and a stable economic infrastructure fostered the best conditions for the lifesupport of a new permanent settlement, including the semi-stable keeping of livestock. Moreover, Doszhan

*Some sources mention his fulfilling the Hajj already when he was 17 (according to the second version of Doszhan Kashakuly’s years of life), that is, in 1832, which can probably be linked to the date on his seal: AH 1248 – 1832/33. However, the reasons for establishing this particular time of his pilgrimage are not entirely clear (see (Khabibullin, (s.a.)).

Kashakuly organized artificial irrigation of a small area of land in the spring zone for cultivating millet, melon, and woody and shrub plants, intending to use agricultural products for the needs of the madrasah and possibly for sale/exchange. Judging by the developed structure of the settlement and large cemetery, the ritual complex functioned quite intensively. The settlement was closely integrated into the economic and cultural life of nomadic cattle breeders, who visited it in the spring and autumn, provided the residents with cattle and fuel, left their children for schooling, and performed the needed rituals at the necropolis (for more details, see (Adzhigaliev, 1994: 58–59)).

Various economic activities (where cattle breeding played the main role) went hand in hand with religious education. The training lasted from three to thirteen years and was carried out using well-known Central Asian textbooks on the Arabic language, Muslim law, religious philosophy, logics, doctrine, metaphysics, and other branches of knowledge. Students were taught not only the basic rules of community life, but also good manners and the culture of public speaking, that is, everything that could later be useful in life. Doszhan-Ishan lived in Kainar for about twenty years, teaching the children of nomads Arabic reading and writing, and giving a more in-depth training to students and followers at the madrasah. The Kainar graduates constituted an entire assemblage of Islamic clergy, who were well-known in Western Kazakhstan, including Ishans, Akhuns, Kazhys, and Khalfes (clergy who reached different levels of training in the four-stage system). Many of them later settled in the Donyztausky District and linked their lives and activities with similar permanent settlements, the number of which increased significantly in the second half of the 19th century.

After imposition of the “Provisional Regulations on Administration in the Steppe Regions…” by the Tsarist government in 1868, which, among other things, limited the activities of the Muslim clergy, Doszhan Kashakuly was forced to move to the north (closer to the Orenburg colonial administration), to the upper reaches of the Oyil River. In this region, he established another ritual and housing complex later named Ishan-ata (to the south of the present-day village of Shubarkudyk). This fact undoubtedly testifies to the great influence and authority of the Ishan among the Kazakhs of the Aral-Caspian Sea region, primarily in the vast area south of the Emba River. Obviously, in his Donyztau period, Doszhan Kashakuly acquired the honorary title of “Khazret” (qazyret)—a high-ranking clergyman and Muslim authority (on a regional scale)—from the clergy and population. Of particular interest for our study is his ideal model of education in the conditions of the long-lasting archaic traditions, in the desert steppe. Doszhan-Ishan offered an alternative to mobile and illegal religious “schools” of the lower level (mektebs), located in dugouts and yurts. This alternative was a self-sufficient educational institution providing accommodation, food, and educational literature, the program of which involved not only teaching literacy and the canons of Islam, but also upbringing and personality development.

Architecture of the site and its main structural elements

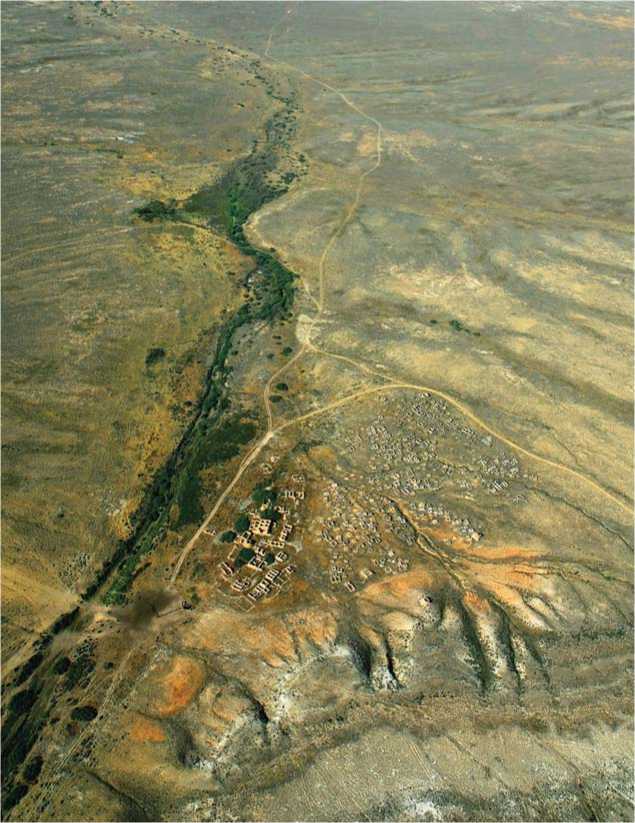

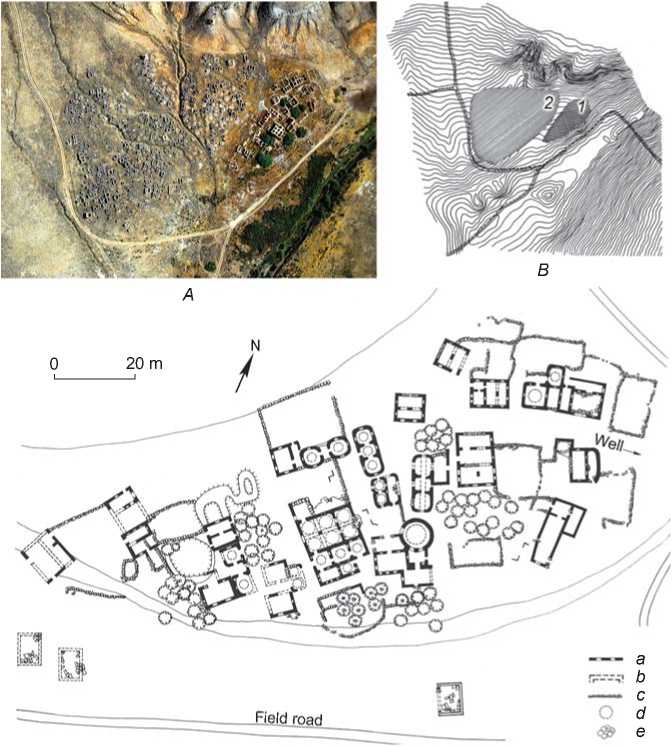

A comprehensive ground survey of the site, including a topographic survey and analysis of aerial photographs, has proven that Kainar RHC is a unique architectural and landscape ensemble (Fig. 2). The complex has a sub-triangular shape (overall size 300 × 200 m; area of 60,000 m2); its long side is oriented east–west and consists of two main parts—the settlement and necropolis, adjoining one other (Fig. 3, A , B ). The site also includes a furnished well in its northeastern corner, a spring ( bulaq ) 600 m to the south, and areas southeast of the settlement between the residential area and the floodplain of the ravine.

The settlement is located in a lowland between the necropolis and the road leading to the well; according to the ground plan, it occupies a relatively narrow wedgeshaped area (160 × 100 m) oriented to the NE-SW (Fig. 3, C ), and includes ruins of numerous (up to thirty) buildings made mostly of blocks of limestone-sandstone. The core of the settlement is the madrasah, representing a group of one-story buildings of various purposes, sizes, and shapes, grouped around a courtyard. Their diversity results from the fact that early examples of madrasahs ( mektebs ) in the south of the Aral-Caspian Sea region were housed in yurts, dugouts, and caves. Therefore, during the initial development of a new Muslim architectural tradition in the Ustyurt, Doszhan Kashakuly had to turn to various sources, primarily Central Asian. This is illustrated, first, by the features of Muslim community life revealed by the Kainar madrasah and known from the neighboring Central Asia in the form of the Sufi khanaka , and, second, by the apt definition given by the Russian geologist S.N. Nikitin to a similar complex established by Doszhan-Ishan later (in Shiylisu)—the “Kyrgyz monastery”.

A madrasah is a Muslim religious and educational institution, which, according to V.V. Bartold, genetically derived from the vihara Buddhist monastery (1966: 112). Historians of architecture define it as a boarding university, architecturally designed in the form of a courtlike spatial structure with public premises (vestibule, darskhana hall, mosque) in the corners of the main facade, and a student dormitory located around the open courtyard (Mankovskaya, 2014: 221). A similar enclosed structure in Kazakhstan appeared only in the later Kalzhan-Akhuna madrasah (near the town of Kyzylorda, early 20th century) (Svod…, 2007: 304–306), while in madrasahs

Fig. 2 . Kainar RHC: panoramic view of the area from the north-northeast ( photo from a hang glider in 2007 by R. Sala and J.-M. Deom ).

in the southern regions, courtyards were open on one or both sides, and had U- or L-shaped ground plans (Svod…, 1994: 238; Svod…, 2002: 91–92).

There are no strict regulations also in the architecture of Doszhan-Ishan’s educational institution. Facing the need for setting up a building complex on a complicated terrain, he erected the madrasah according to the principle of an asymmetric, but spatially balanced composition. The courtyard appeared on an elevated space; it was freely surrounded by free-standing buildings that only marked the boundaries of the site: the southwestern corner was occupied by the mosque complex; the southeastern corner was a yurt-like structure with added spaces; the northeastern and northwestern corners were dormitory buildings.

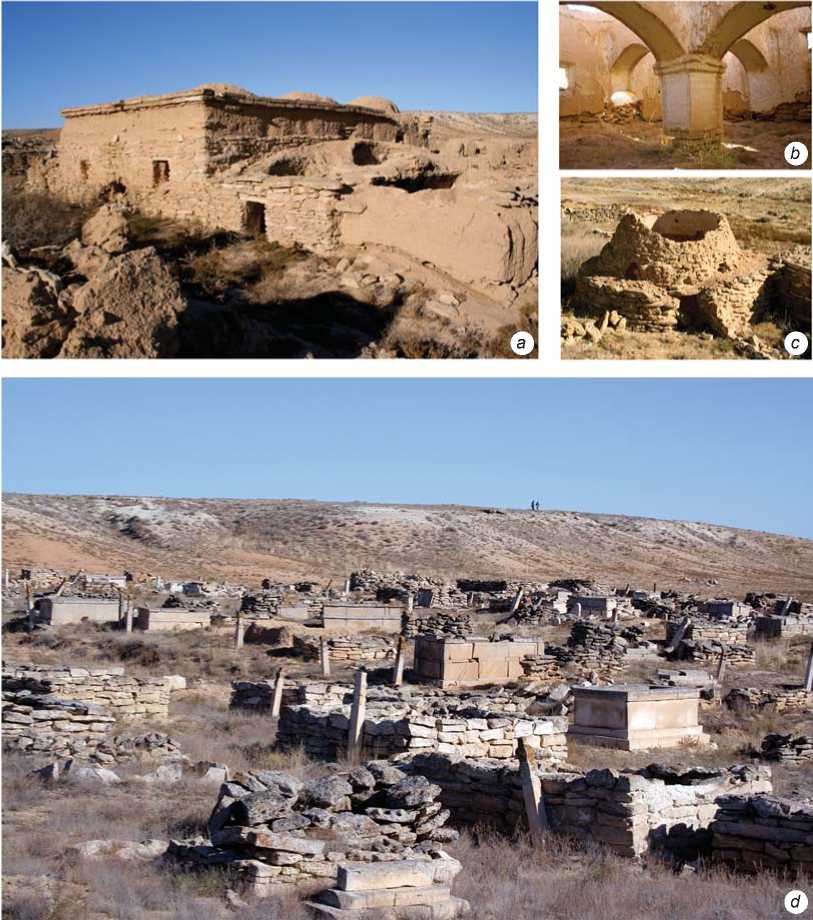

The individual components of the Kainar madrasah should be described in more detail. Distinctive points of its layout, like in any other madrasah, were public halls and their place in the overall composition. The first group was the mosque complex. It consisted of a relatively large building of sophisticated outline, with walls made of hewn stone on clay mortar without a foundation; the upper part of the walls and dome were made of adobe bricks. The core of the composition was the mosque oriented to the NE-SW (size of 13.2 × 9.2 m, height 4.7 m), which reveals the pattern of Central Asian pillar-and-dome (two pillars and six domes) mosques for regular daily prayer (Fig. 3, C, in the center; 4, a). For creating a vestibule, two compartments with domes were separated inside by a massive partition; a central pillar with arches resting on it with pendentives in the form of concave triangles, remained in the square of the walls in the prayer hall (Fig. 4, b). This carefully plastered and whitewashed space was illuminated by window openings; they flanked the semicircular niche of the mihrab on the southwestern wall. Two doorways connected the prayer hall with an

B

А

20 m

Fieldroad а b c d e

Fig. 3 . Planigraphy of the Kainar complex.

A – orthogonal top view ( photograph from a hang glider in 2007 ); B – situational diagram ( based on the instrumental survey of 2005 ): 1 – settlement, 2 – necropolis; C – settlement ground plan ( measurements of 2005 and 2007 ).

a – surviving wall structures; b – conjectured walls and arches; c – stone enclosures; d – conjectured domed vaults; e – green spaces.

entrance room; two more doorways led to side annexes. It seems that there was a utility room to the right of the mihrab , and library and classrooms to the left of it.

The second public hall of the madrasah can be interpreted as an auditorium for reading aloud of the Quran. It occupied the southeastern corner and was a round-shaped (with internal diameter of 10 m), tower-like structure in the form of a high sphero-conical red brick dome raised on a massive cylindrical stone base with wide opening of the front entrance from the courtyard (Fig. 4, c ).

The third hall was one of the premises in a building located to the northeast of the khujras (cells), and most likely was intended for collective ritual meals. It is square in plan view, relatively spacious (5.5 × 5.6 m), festive (abundance of window openings and decorative niches, figurative stonework on arches, etc.), and has a massive pillar in the center. Two wide arches rest on the pillar;

the other ends of the arches rest on the walls across the premise. The presence of a hearth with chimney inside this pillar makes it possible to discern a religious meaning in it. Parallels can be drawn with the “alouhana” of mountainous Tajikistan, as well as “houses of fire” and kalyandarkhana of Khwarazm (Snesarev, 1963: 197– 199). In addition, the sacred connection between fire and wood is well known (Snesarev, 1969: 193). We can add another similarity from the Islamic tradition. The surah “Light” (Quran, 24, 35) speaks of the “blessed wood”, that is, wood full of spiritual radiations—symbol of the Light of Allah (Koran…, 2003: 383). All this once again confirms that the madrasah of Doszhan-Ishan belonged to an individual unit of the Sufis.

The khujras intended as dwellings for students and teachers surrounded the courtyard to the north and east; some of them were located to the west of the mosque. These buildings corresponded to different stages and

Fig. 4 . Architecture of the Kainar complex.

a – general view of the mosque from the south; b – interior view of the prayer hall; c – general view of the madrasah public hall; d – necropolis (central part). Photographs of 2005 .

forms of the transition from nomadic to sedentary life: semi-dugouts were interspersed with adobe and yurt-like structures, possibly also with felt yurts. Remains of more permanent residential buildings, often with fenced plots, have survived in the northeastern part of the settlement; they might have belonged to the head and teachers of the school.

The second part of the Kainar RHC was the ensemble of the necropolis located on its western side, which appears to be almost as successful in its compositional structure as the settlement. This is the largest memorial complex of the Ustyurt. Its artistic totality comprised structures of various types and times of the second half (or the end) of the 18th to early 20th centuries, manifesting the features of their periods of construction (Fig. 4, d). There are about a thousand monuments (including composite structures) over the burials of the deceased from the Kazakh clans of Tabyn, Adai, Shekty, etc. Large monumental structures are interspersed with smaller varieties; almost all of them were made of local sandstone-limestone. Many structures above the graves have turned into shapeless ruins, lopsided, weathered, corroded by salt, and showing traces of patina. Nevertheless, they exemplify the entire spectrum of monuments of memorial architecture in the Mangystau-Ustyurt region and genesis of their forms.

About half of the sites are representative; they are distinguished by a variety of types and richness of artistic decoration carved in stone (over fifty monumental structures and five hundred small forms); the rest are archaic varieties, such as grave mounds, stone placing, stone enclosures, small crude steles, boxlike structures, etc. Large monuments—tombs of the heads of clan units and wealthy steppe inhabitants— at the Kainar necropolis are represented by single mausoleums and predominantly by saganatama , architectural enclosures. Only three mausoleums have been identified; one of them is in a semi-ruined state and in fact represents a giant enclosure-“mausoleum”. Two other structures, which have retained the features of domed buildings, are located in the northern part of the necropolis. One of them was built on a hill in a separate section of the cemetery ( qaýym ). A detailed examination of another site on the lowland—the memorial to Kozhym Zhankutuly from the zhalpaqtil unit of the Shomyshty-Tabyn clan*—shows that this was a typical version of the centric tiled mausoleum of the Mangystau-Ustyurt type of the 1870s–1880s, consisting of a low base with three-layered walls (with external facing) and small simple dome in the corbel vault technique.

The saganatamas belong to the last third of the 19th– early 20th centuries. The dominant type was transverse-axial (east–west), not very large and designed for one burial (for more details, see (Azhigali, 2002: 306)). Many structures of this type show typical signs of professional architecture: individualization of form, careful preliminary processing of wall and decorative material (sawn blocks and slabs), very careful structural design, and additional decorative processing (facing, carving, painting, etc.). Yet, archaic features typical of the memorial architecture of the Donyztau region, such as rough texture of stone material, large-sized decoration, etc., are also evident in the general appearance of these structures. Practically no large family saganatamas in the necropolis have been found, as opposed to occasional large family enclosures of the qorgan type, built not of sawn stone blocks, but of stone blocks with primary processing.

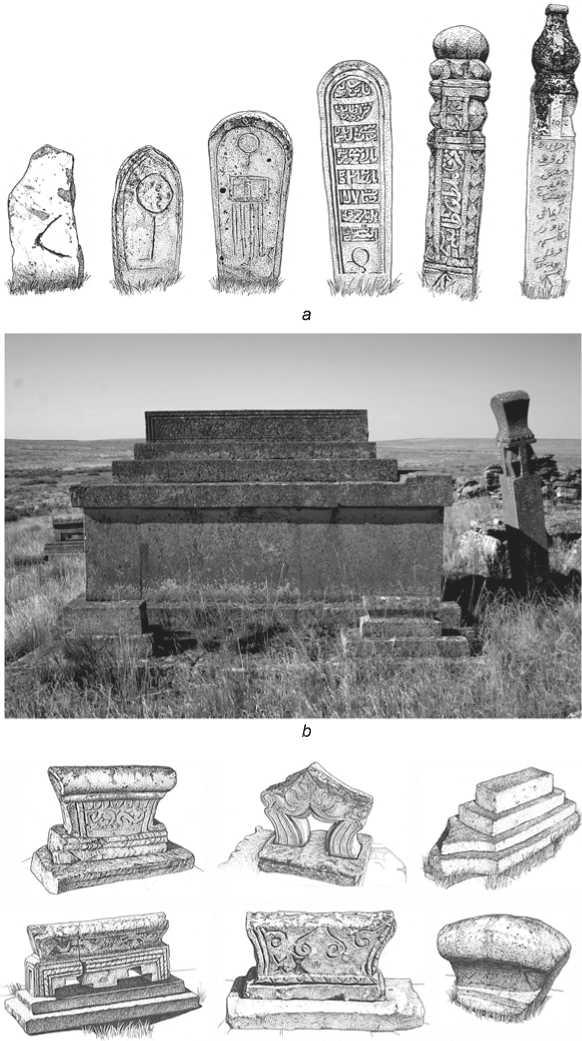

Small forms of memorial architecture are very diverse in Kainar, with the domination of kulpytas steles and tombstones (for more details on the typology of the monuments, see (Ibid.: 319–353)). The kulpytas steles are mainly represented by two types: 1) coarse flattened steles of small size (no more than 0.7 m) with an expressive silhouette, pointed or semicircular pommels, and tamgas in the center of the front plane, and 2) artistic kulpytas steles—flat and four-sided carved pillars of medium size and taller than the height of a human, often with tiered composition (Fig. 5, a ). Sites of this type retain the main features of stone-cut steles of the Mangystau-

Ustyurt region in their overall composition (body – transitional part – pommel) and external processing (moderate ornamental decoration in flat relief, epitaphs on the western edges with tamgas in the Arabic script, and occasional “drawings”). Notably, the Kainar kulpytas structures are generally canonical and standard; there are no particularly outstanding examples (giant monuments, unique carvings, etc.), but there are many well-done and solid steles.

Different varieties of stone structures above the graves include stepped koitas , ushtas , and bestas structures, as well as box-sarcophagi ( sandyktas ), and look more distinctive. Three main groups can be stylistically identified among the widespread koitas structures in the Mangystau-Ustyurt region, which typically show division into two main parts—the pedestal and upper “body”: classic, including archaic varieties; those on “legs”; and unique gravestones (Fig. 5, c ). Archaic monuments (for example, the “Turkmenoid” gravestones with arched “bodies”) can be dated from the first half to mid 19th century, but the bulk of koitas structures at the necropolis belongs to the second half of the 19th century. Undoubtedly some unique items are noteworthy.

The stepped ushtas (‘three stones’) and bestas (‘five stones’) gravestones at the Kainar cemetery are distinguished not only by their number (their largest concentration is in the northern Ustyurt area), but also by their variety, and often by originality of forms and compositions. This stylized type of gravestones in the form of a pyramid with prominent upper bar is quite late (late 19th–early 20th centuries); it occurs not only as individual monument, but also as a single grave structure for two or three burials on a common platform. We should also mention specific functional aspects of such sites: they were found mainly above children’s burials, since the structural features of smaller graves made it possible to set up such heavy structures. Original gravestones were not uncommon among stepped gravestones at the necropolis, and included items in which the upper rectangular prism was covered with decoration in flat relief, epitaphs in the Arabic script, unusual outline of the slabs, etc.

Such an distinctive category of small memorial architecture of the Kazakhs as box-sarcophagi sandyktas structures (“stone boxes”) appeared at the Kainar cemetery to a lesser extent. Two groups can be identified: a small accumulation of archaic monuments with the tamga of the Adai clan in the southern part of the necropolis, which apparently dates back to the second half of the 18th century (possibly, the early 19th century); and several more distinctive artistic sandyktas structures of the late 19th–early 20th centuries, scattered throughout the complex, which include some outstanding examples of stone carving architecture. Such is, for example, the sandyktas of 1881/82 at the southern edge of the cemetery, forming the base of an interesting composite structure with an upper stepped gravestone, kulpytas stele, and two children’s gravestones (Fig. 5, b). The exclusivity of the site was also emphasized in the epitaph, where the stone cutter Zhalgali Zhantoreuly was mentioned.

In addition to stone cut structures described above, there are many simpler grave monuments at the necropolis: collapsed mounds and stone placements, enclosures of unprocessed or preprocessed stone blocks and slabs, etc. All of them, as a rule, are an integral part of composite structures. The same applies to the categories of stone cut monuments described above (steles, gravestones, sarcophagi), which extremely rarely occur in their “pure” form. Precisely the combination of their types and varieties creates (as in other necropolises of the region) a particular richness of monuments at this unique memorial complex. Composite grave structures constitute the overwhelming majority of objects at the necropolis. Particularly popular are the “clusters” kulpytas -tombstone (of the koitas type, stepped, or sandyktas ), kulpytas -enclosure, kulpytas - saganatam -tombstone, etc. They have some common features, such as longitudinal axis of the structure (excluding mausoleums and large saganatamas ) with east–west orientation, with a stele installed at the western end, and stylistic variety of the constituent elements.

Undoubtedly, decorative and informational rendering of stone carved monuments, which has received the conventional definition of “text” (or “texture”) in scholarship, is also of great interest. These include inscriptions (epitaphs) in the Arabic script, clan signs (tamgas), subject and compositional images (“drawings”), as well as ornamental decoration. Without going into detail concerning the pictorial features of the tombstones, which is a subject for separate research, and referring to the already published studies (see (Azhigali, 2002: 448–495)), we should make only a few points. In particular, the epitaphs (in Kazakh) on the monuments of the necropolis, mainly on the kulpytas structures, are of great interest for attribution of the structure, and as historical, social, and philological sources. An example would be the inscription on one of the steles of 1880/81, where it is indicated that

c

Fig. 5 . Small forms of architecture. a – kulpytas funeral structures, mid 19th–first half of the 20th century; b – sandyktas

funeral stone boxes, late 19th–early 20th century ( photograph of 2007 ); c – gravestones (of the koitas type, stepped), mid 19th–early 20th centuries.

the buried person was “Damla Ýrazgali Musauly”, that is, a da mullah—highly learned chief mullah. Taking into account the presence of the madrasah, the servants of whom were obviously buried in this cemetery, such information is of great historical and cultural value.

A special subject of research are the tamgas of the necropolis. As was already mentioned, they were studied from the point of view of applied science (for establishing the nomadic routes) by the geographer S.V. Viktorov (see above). The expedition carried out a targeted study of clan symbols at the complex. The prevailing tamgas were of the Shomyshty-Tabyn (in various versions) and Adai clans; there were a number of signs of the Shekty clan, and individual tamgas of the Zhappas and Tarakty-Tabyn clans. Particular clan groups dominated over specific, large areas of the cemetery.

As far as “drawings” and ornamental decoration of the monuments are concerned, they were not as distinctive as decoration appearing in the complexes from the more southern Mangystau-Ustyurt region and some necropolises of the northern Ustyurt zone. The patterns are often standard (plant decoration). The moderate nature of these elements results from both the general unadorned and sparse style of Donyztau tombstones and certainly from the presence of the Islamic religious center and its authoritative servants in Kainar.

The necropolis, located in the immediate vicinity of the settlement, was an integral part of the entire complex. They were traditionally set up on somewhat elevated places; they grew to the left or right in groups depending on the tribal and clan affiliation and terrain, and represented a kind of settlement of the dead—a completely real and at the same time absolutely otherwordly space with graves of the ancestors and objects of mystical and religious worship. The cemetery was also a significant object of the wider cultural space, since it was also used by nomadic cattle breeders living in this part of the Ustyurt. The architectural environment of the necropolis expressed various meanings. The graves of the ancestors symbolized tribal unity and connection of generations, and satisfied the need of the steppe inhabitants for orderly and direct contact with the sacral world. The graves were one of the ways of thickening and spiritualizing the space of the settlement, primarily of the local Islamic educational institution.

Discussion

A hypothetical reconstruction of the Kainar ritual and housing complex, based on the thorough field study, has shown that this type of settlement optimally corresponded to local conditions of terrain, climate, and hydrology. The most important feature of its structure was well-developed differentiation of the site (public-residential, educational, economic, and production areas), which entailed multilayering. The core of the settlement (the madrasah) was surrounded, on the one side, by dwellings, cattle pens, and utility buildings, and on the other side, by the necropolis. The outer layer comprised economically developed territory and included water sources, pastures, protected areas, crops, etc. The zoning does not reveal hierarchy or clear boundaries; these were constituted by natural barriers. All these features fit the understanding of the term “ensemble” in architecture and make it possible to formulate the principles of architectural and spatial organization in the Kainar RHC: structuredness, functionality, ecological compatibility, “open form”, and visual localization.

Conclusions

The integrated adaptation of the Muslim religion by the nomads of Western Kazakhstan, who perceived it as the new spiritual basis of their personal and social life, led to material embodiment of the ideas of Islam (monotheism, prayer, pilgrimage; correlation of the axes of burial = monuments with orientation to Mecca) in the forms of the life-supporting environment (mosque, madrasah) and traditional artistic culture (types of monuments, Arabic epigraphy, etc.), taking into account regional social, architectural, and building traditions. The interaction between the new forms of religious architecture and commemorative traditions of the Kazakhs resulted in the creation of a unique ensemble, where the spatial relationships of the educational institution, residential and production areas, placement of religious objects, microclimatic conditions in an extreme external environment provided the necessary level of physiological and psychological comfort.

In other words, the perception of the vast and harsh landscapes of the arid zone became a part of the experience for the nomads; the chink cliffs of the Ustyurt entered the system organized through art; from indifferent nature with its eternal beauty the cliffs turned into the material memory of radical transformations in the life of the Kazakhs, origins of their educational religious centers, and the consolidating image of the outstanding man of faith Doszhan-Ishan, who selected the necessary range of cultural codes for implementing the goals he set.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Project No. AP08857659.